Abstract

Thirty-three among 441 research articles published in the Journal of Family and Economic Issues during the past decade (2010–2019) examined financial behavior. Through content analysis, we describe what these studies have discovered and discussed. Savings, wealth, and family issues were the keywords chosen most frequently. Studies primarily implemented quantitative analyses, such as regression and regression-like analysis, using secondary data collection methods, and the majority investigated financial behaviors of US individuals or households. Based on the findings, future research directions on financial behaviors are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the four decades since the Journal of Family and Economic Issues (JFEI) was founded in 1978, it has served as one of the leading research journals in consumer finance and economics. The JFEI’s goal is to examine the relationship between the family and its economic environment and it has contributed to important findings relevant to family management, the household division of labor and productivity, relationships between economic and non-economic decisions, and the interrelation of work and family life, among others. Among studies of the journal’s various scopes and topics, the primary purpose of this article is to provide insights into the trends in research in financial behavior published in the JEFI over the past decade (2010–2019).

Xiao (2008) defined financial behavior as any human behavior relevant to money management and pointed out that many researchers have focused on cash, credit, and saving behaviors. Financial behavior of individuals or households has identified determinants, the relationships among key variables, and provided implications and suggestions. Financial behavior is associated with financial outcomes and financial wellbeing. For example, some financial behaviors, such as a mortgage and other consumer loans, have profound implications for consumers (Collins 2011). Financial behavior is also associated with non-financial domains of life (e.g., happiness and life satisfaction), and engaging in positive financial behavior may help produce other positive achievements in life (Totenhagen et al. 2019). Studies on financial behavior have suggested the importance of applying findings through financial counseling, planning, and education to improve financial behavior and decision-making of individuals and households (Gillen and Kim 2014; Lown et al. 2015). Thus, exploring studies on financial behavior provides a current profile of consumer engagement in financial transactions and provides insight into what to research and teach, and what services related to financial behavior need to be addressed in the next decade.

This study focused on important aspects of publications of which researchers, educators, practitioners, and policymakers should be aware, including an overview of trends in research topics, methods, data collection, secondary datasets used in articles, and geographic location, as well as directions for future research in financial behavior. In particular, this study conducted a content analysis of four domains: (1) Keywords; (2) research methods; (3) data collection and secondary datasets, and (4) geographic location. The article is organized as follows. First, we review the primary focus of 33 selected studies. Then, the methods section describes the way we analyzed the keywords, research methods, data collection and secondary datasets, and geographic location. The results section presents our findings, and the last section discusses future directions for researchers in financial behaviors.

Review of Selected Studies

From 2010 through 2019, the JFEI published 10 Volumes, 40 Issues, and 441 research articles, excluding the editor’s notes, and this study examined 33 original research papers on various financial behaviors published in the journal. In this section, we summarize all 33 studies’ main research focus or purpose in chronological order before more detailed content analyses of the similarities and differences among the articles.

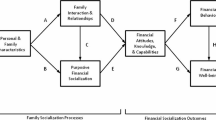

Eight articles were selected from Volume 32 published in 2011. Fisher and Montalto (2011) analyzed the effect of a change in income on saving behavior following the framework of loss aversion and Yao and Curl (2011) examined changes in risk tolerance in response to stock market returns over time. Dew (2011) identified the association between unsecured consumer debt and the likelihood of divorce with the mediating role of financial conflict, and Levinger et al. (2011) investigated the relationship between credit knowledge and financial outcomes. Collins (2011) explored problematic mortgage application behaviors, and Fontes (2011) analyzed differences in retirement savings between native- and foreign-born individuals. Marsden et al. (2011) examined the value of financial advice in various retirement planning behaviors, and Kim et al. (2011) investigated the association between the contribution of family processes and young individuals’ financial socialization.

Two articles from Volume 33 published in 2012 and three articles from Volume 34 published in 2013 were selected. Among the articles published in 2012, Smith et al. (2012) analyzed the relationship between financial sophistication and housing leverage among older households, and Kim et al. (2012) examined the effect of cognitive ability and bequest motive on stock ownership among the elderly. In 2013, Fisher (2013) investigated the presence of loss aversion in household saving behavior in Spain, and Whitaker et al. (2013) identified the gender role in household saving behavior. Haron et al. (2013) analyzed saving motives of a Malay Muslim sample based on the framework of a hierarchy of savings.

Eight articles were drawn from Volume 35 (four articles) and Volume 36 (four articles) published in 2014 and 2015, respectively. Leonard and Di (2014) analyzed financial behaviors’ influence on the duration of asset poverty, and Lee et al. (2014) examined the entire array of household outlays to compare the expenditures between one- and two-earner married households. Gillen and Kim (2014) investigated the role of personality traits in the receipt of financial help among older households. West and Worthington (2014) focused on the impact of transitory macroeconomic conditions on changes in risk tolerance of households in Australia. Pastrapa and Apostolopoulos (2015) examined factors associated with borrowing behaviors of urban households in north-eastern Greece, and Yao et al. (2015) identified directly reported saving motives of Chinese consumers in urban areas. Duh et al. (2015) investigated the effects of disruptive family events experienced during adolescence on the materialism of young adults in France and South Africa, and Lown et al. (2015) examined the association between self-efficacy and saving behavior among middle- and low-income households.

Seven articles were taken from Volume 37 (three articles) in 2016 and Volume 38 (four articles) in 2017. Griesdorn and Durband (2016) analyzed the relationship between young Baby Boomers’ (those born between 1957 and 1964) self-control and household wealth, and Park and Yao (2016) investigated the effects of seeking sources of information on households’ construction of portfolios. Grable and Watkins (2016) tested the extent to which stamp collectors (those owning collectible classic US postage stamps) experience an opportunity cost associated with expenditures on their collections, and Woosley et al. (2017) explored factors associated with the combination of the medical and financial end-of-life planning actions taken by adult children within a family. DeBoer and Hoang (2017) tested the correlation between the receipt of an inheritance and the expectation of leaving a bequest, and Manly et al. (2017) examined the effects of cultural capital on parents’ financial planning for their child’s college education. Moreno-Herrero et al. (2017) investigated factors related to retirement saving decisions of households in Spain.

Lastly, one article from Volume 39 in 2018 and four articles from Volume 40 in 2019 were used. Camões and Vale (2018) analyzed the link between wealth perceptions and portfolio composition of Portuguese homeowners, and Copur and Gutter (2019) identified economic, sociological, and psychological factors associated with saving behavior of university employees in Turkey. Totenhagen et al. (2019) examined the role of subjective and objective financial knowledge on relationship satisfaction using a sample of cohabiting or married young adults, and Cheung and Yilmazer (2019) explored the link between older households’ severe memory problems and portfolio choice. Choi and Wilmarth (2019) investigated the association between financial assets and bequests expectation with depression symptoms as the moderator.

Methods

We examined the similarities and differences among these 33 research papers on financial behaviors published in the JFEI through content analysis. The content analysis provided a comprehensive portrait of the recent trends in financial behavior research according to certain key aspects: (1) Keywords; (2) research methods; (3) data collection and secondary datasets, and (4) geographic location.

Keywords

The taxonomy for classifying keywords entailed a two-step procedure. Each article included 3–6 keywords and over 130 keywords were listed in the articles selected from Volumes 31 (in 2010) to 40 (in 2019). Keywords are a medium that represents the content and topic of the manuscript. Thus, keywords allow readers to identify a study’s primary topic, find papers in their field of interest more effectively, and help them focus on an article’s major findings or arguments throughout reading (James and Cude 2009). To identify the articles’ major focus and content through keywords, we reviewed all author-supplied keywords and count frequencies of each keyword first. Then, we displayed keywords using a word cloud method that provides a visual representation of prominent keywords based on their frequency of use in the text data. Secondly, we classified 33 articles into smaller groups with a similar research topic or focus after matching the keywords with each article’s overall research content (e.g., topics, findings, title). This allowed us to capture certain levels of uniformity in the research topics and content among the articles even though they used different keywords.

Research Methods

We examined the articles according to the way they analyzed the data about financial behavior. Given that all 33 articles were quantitative studies, their data analysis was classified into three categories: (1) descriptive; (2) regression or regression-like, and (3) other analyses, following James and Cude (2009) and Ji et al. (2010). The first category, descriptive analysis, includes univariate analyses such as frequency distributions, dispersion (e.g., range, variance, standard deviation), and central tendency (e.g., mean, median, mode), as well as bivariate analyses, such as comparisons between variables (e.g., t-test and Chi-squared test) and correlations to describe and summarize data through sample characteristics and distributions and relationships among variables. If the most advanced analysis methods used in an article were any form of descriptive statistics, the article was classified into this category. The second category, regression or regression-like analysis, includes Ordinary Least Squares, Probit, Tobit, logistic, Heckman, Cox proportional hazard ratio regression, Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition regression, propensity score matching, continuation ratio logit, quantile regression, and other types of regression analyses. The last category, other analysis, includes all other quantitative analyses, such as factor analysis, path analysis, ANOVA, MANOVA, and structural equation modeling.

Data Collection and Secondary Datasets

To explore the similarities and differences in research methods further, we approached the research method based on (1) characteristics of data collection, and (2) sources of secondary data following James and Cude (2009) and Ji et al. (2010). The characteristics of data collection were identified as either primary (e.g., surveys, interviews, experiments) or secondary data (e.g., secondary dataset, government statistics, market research reports or publications, corporate or research institution websites). In addition, the sources of secondary data were discussed at the regional (e.g., surveys in one state), national (e.g., surveys across the US), and international levels (e.g., surveys outside the US).

Geographic Location

We explored studies by author affiliation and the 33 studies’ data traits following McGregor (2007). Studies were categorized by the authors’ geographic locations or their use of data that covered certain geographic locations around the globe, including the US, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia. Further, we compared the author’s affiliation and data’s geographical location between international studies and US studies by data collection methods.

Results

Keywords

A word cloud represents keywords with the size of the text according to the frequencies of the word in the text data, which indicate the keywords’ relative importance among the studies. Keywords used more frequently appear larger and bolder in the cloud. We created a word cloud using 134 keywords in all 33 articles and Fig. 1 shows that those used most frequently were “financial” (18 times), “savings” (11 times), “planning” (5 times), household (4 times), retirement (4 times), and risk (4 times).

To discover further similarities and differences in research topics and content among articles that cannot be identified fully with keywords alone, we reassessed the keywords and the research content (e.g., topics, findings, title) and sorted articles into groups with a similar topic or focus. We classified the 33 articles into the following ten categories: Savings; wealth; family issues; financial advice; risk tolerance; debt; financial knowledge; investment; retirement, and inheritance. Table 1 presents the top three areas the studies examined frequently. “Savings” was the top-ranked research topic, which includes saving behavior, retirement savings, saving motive, and college savings. For example, Fisher and Montalto (2011) examined the effect of a change in income below the household’s reference level on household savings within the framework of loss aversion. “Wealth” and “family issue” were tied for second place and analyzed in five articles. For example, Leonard and Di (2014) analyzed factors associated with the likelihood of reentry into asset poverty after an exit. In particular, “family issues” included family structure, divorce, family disruptions, family environment, and parenting. Kim et al. (2011) investigated the associations between family processes (e.g., parental warmth and financial monitoring) and adolescents’ financial behaviors. Other primary topics or contents covered in the studies were financial advice, risk tolerance, and debt issues.

Research Methods

Of the 33 articles published in the last decade, most used multivariate analysis in addition to the descriptive statistics for the analytic sample and main variables. As illustrated in Table 2, three studies (9.1%) were identified as either descriptive or other analysis. For example, Grable and Wakins (2016) used correlations, means, and standard deviations primarily to calculate advanced ratios and estimate the opportunity cost of financial behavior (i.e., collecting stamps as a hobby). Two other studies used path analysis and structural equation modeling, classified as “other analysis.” The remaining 30 articles (90.9%) employed regression or regression-like statistical methods, in which the primary analytic model was either the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) or logistic regression model.

Data Collection and Secondary Datasets

Of the 33 articles, 7 (21.2%) conducted primary data collection and 26 (78.8%) used secondary data, i.e., data collected by others or for other research purposes (Table 3). Most of the articles employed primary or secondary survey data of individuals or households to analyze financial behavior, but several used publicly available data (e.g., government statistics, market research reports or publications, corporate or research institution websites). A majority of the studies with secondary data used a national or international survey dataset of individuals or households, except for one that used market price data (e.g., retail stamp prices listed in Scott’s Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers, Stock and bond returns from the Stern School of Business at New York University). None of the articles were non-empirical studies, such as a conceptual or review paper.

Table 4 shows the sources of datasets among those articles that used a secondary dataset of individuals or households collected at different levels. The national survey dataset used most frequently was the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), with five articles, followed by the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) with four articles. Two studies used the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) and the other two used the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP). Five other US public datasets were used: The Consumer Expenditure Survey (CE), National Longitudinal Survey of Youth (NLSY79), Home Mortgage Disclosure Act Data (HMDA), National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH), and National Center for Education Statistics (NCES).

At the regional level, two studies used survey data in a confined geographical location of respondents: The Wisconsin Longitudinal Study (WLS) and Arizona Pathways to Life Success for University Students (APLUS). Lastly, six studies used international secondary survey datasets. Two studies used the Survey of Household Finances (EFF) of the Bank of Spain and four other studies used either the Household, Income, and Labor Dynamics in Australia (HILDA), Survey of Chinese Consumer Finance and Investor Education (SCCFIE), Portuguese Household Finance and Consumption Survey (HFCS), or Economic and Financial Aspects of Aging in Malaysia.

Geographic Location

The 33 articles represent the work of authors from nine different countries based on five continents (the Americas, Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia). Specifically, based on their affiliation and the data they used, 24 articles (72.7%) were written by US-based authors who used US data, five articles were published by non-US affiliated researchers who used non-US data (i.e., Greece, Spain, Portugal, France, Africa, and Australia), and four articles were crosses in which US researchers worked on non-US data, non-US researchers worked on US data, or a combination of the two (e.g., US, Spain, Korea, China, Malaysia) (Fig. 2).

Three of the nine non-US based studies that analyzed international data or whose authors were not based in the US, used primary data collection, which accounted for 33.3% of the total international studies. Primary survey data were drawn from Greece, South Africa, France, and Turkey, and thus, more non-US studies used primary data than did US studies. Four US studies used primary data collection, including the NC 1171 research project online survey, an online survey at a Mountain West university, a survey of credit counseling recipients, and Michigan State University’s Institute for Public Policy and Social Research survey. Both at the national and international levels, a majority of studies used secondary data to analyze financial behaviour (Table 5).

Major Findings of Selected Studies

The full results of each domain in our content analyses (i.e., keywords, research methods, data collection, and geographic location) are discussed above. In this section, we revisited the main findings of the research papers on financial behaviors based on their topics/purposes: (1) Saving; (2) wealth and investment; (3) debt and credit; (4) family factors and relationship issues; (5) financial planning; (6) financial risk tolerance, and (7) others.

First, household saving behavior was discussed more extensively than the other areas with respect to its conceptual, theoretical, and methodological aspects. Some studies examined saving behavior to test theoretical models empirically. Fisher and Montalto (2011) and Fisher (2013) analyzed the likelihood of saving based on the framework of loss aversion and the importance of a reference point in financial decision making. Fisher and Montalto (2011) found that having a lower level of income relative to the household’s reference level decreases the likelihood of saving significantly, while Fisher (2013) did not find supportive evidence of loss aversion in Spanish households’ saving behaviors.

Some studies were based on a conceptual framework or theories to analyze various contributing factors associated with household savings. Fontes (2011) focused on ethnic identity and acculturation to examine immigration status as a factor in retirement savings asset use between Latin American immigrants and the native-born, while Whitaker et al. (2013) approached saving activity (e.g., predicting savings plan participation) with a focus on gender’s different effects based on family development and feminist theory. Lown et al. (2015) used social cognitive theory to explain the relationship between self-efficacy and saving and found that higher levels of self-efficacy were associated with a greater likelihood of saving. Some researchers analyzed household saving behaviors in other countries. Yao et al. (2015) identified Chinese households’ three saving motives (i.e., emergency, children’s education, and retirement) reported most commonly based on the life-cycle hypothesis. Haron et al. (2013) used both economic and behavioral models and found that family size, educational level, health perception, income quintiles, and income adequacy were important predictors of moving from a lower to a higher level in the saving motive hierarchy among older Malay Muslims. Lastly, Copur and Gutter (2019), whose conceptual model was based on the life cycle hypothesis, the theory of planned behavior, and social cognitive theory, found that homeownership and financial management behaviors were related significantly to Turkish university employees’ household saving.

Second, studies analyzed household wealth and investment behaviors. Kim et al. (2012) began with a theoretical proposal that investment participation occurs only if the return is expected to be greater than the cost of participation. Thus, cognitive abilities, which would determine their cost of participating in the stock market, and bequest motives that reflect the expected utility of investments, were analyzed with the elderly’s stock ownership and purchase. They found that elderly households’ cognitive ability and bequest motives were associated positively with stock ownership, and the bequest motive was associated positively with stock purchase. Leonard and Di (2014) explored asset poverty dynamics and the wealth threshold by testing determinants of the likelihood of escaping and returning to asset poverty, and confirmed the presence of structural barriers to asset accumulation (e.g., exit, reentry). Based on the behavioral life-cycle hypothesis, Griesdorn and Durband (2016) found that investment in human capital, homeowners, and higher self-control were related positively to young Baby Boomers’ wealth accumulation. Camões and Vale (2018) found that the average annual growth rate of residential property valuation was related to the perceived wealth and portfolio composition of households. As the rate of housing valuation increased, the portfolio became more diversified. Lastly, Cheung and Yilmazer (2019) found that memory loss through the mediating effect of cognitive ability was associated positively with the elderly’s portfolio decisions, such as risky assets ownership, the amount of risky assets, and financial wealth.

Third, researchers investigated financial behaviors related to debt and credit. Levinger et al. (2011) emphasized the importance of self-assessment of credit scores in financial literacy by finding that many respondents did not know their credit scores and underestimated their creditworthiness, all of which would explain perceived credit constraints, and credit contracts, such as credit card interest rates. Collins (2011) found that tract-level college completion rates, homeownership rates, and household age, race, ethnicity, and income were related to problematic loan application behaviors (e.g., submitting incomplete paperwork, withdrawing a loan application before the lender makes a credit decision, rejecting a lender-approved loan offer, accepting a high-interest rate loan). Smith et al.’s (2012) study was based on the life cycle hypothesis and found that liquidity constraints and financial sophistication were important factors associated with household leverage. Lastly, Pastrapa and Apostolopoulos (2015) found that homeowners and credit card holders were more likely to obtain loans, while savers were less likely to do so. Further, income, homeownership, the proportion of working family members, saving, and age influenced the loan amounts. For example, those who saved and homeowners had a lower loan amount, while older respondents had a high loan amount.

Fourth, some studies analyzed financial behaviors related to family factors and relationship issues. Dew (2011) used social exchange theory to explain the way expectations of each other, relationship dissatisfaction, and financial disagreement are related. He found that marital satisfaction mediated the association between debt and the likelihood of divorce (i.e., the more debt, the increased likelihood of divorce), and the association was mediated by financial conflict and marital satisfaction. Kim et al. (2012) highlighted family processes and financial socialization (parental warmth and financial monitoring, parent–child interactions about money) that influence financial practices (saving for future schooling, child’s contribution to family expenses, child’s bank account ownership, child’s donation, child’s financial anxiety) among children and adolescents. They found that family processes and parent financial socialization were associated positively with children’s financial socialization and practices. Lee et al. (2014) discussed household production characteristics and dynamics and found that dual-earner couples contributed more to private pension plans, and allocated financial resources for future consumption, which results in lower current-period consumption. Duh et al. (2015) discussed financial resources as a type of human capital, and peer communication about consumption as a socialization process based on the life-course paradigm to explain the development of materialistic attitudes. They found that family resources received during adolescence were a positive factor in French young adults’ materialism, while they were not significant in South African young adults’ materialism. Peer communication was related positively to materialism in both samples. Lastly, Totenhagen et al. (2019) found that subjective financial knowledge was associated with relationship satisfaction and there was an indirect effect of perceived shared financial values on the relationship based on social exchange theory.

Fifth, some researchers analyzed financial planning behaviors. Manly et al. (2017) discussed parents’ financial planning for their children’s education and noted intergenerational transmission via capital conversion from cultural to economic capital in the form of parental financial investments (financial preparation, savings) in schooling for their children. They found that parental involvement was the most important factor in the engagement in financial planning for children’s college education. Marsden et al. (2011) discussed financial planning for retirement and found that working with a financial advisor was related positively to retirement planning activities (i.e., setting goals, calculating retirement needs, retirement account diversification, use of supplemental retirement accounts, accumulation of emergency funds, positive behavioral responses to the recent economic crisis, and retirement confidence), while working with a financial advisor was not associated with self-reported retirement saving and short-term growth in retirement account assets. Other studies discussed estate planning. Woosley et al. (2017) found that net worth, parents’ completion of a living will, and adult children’s avoidance of death ideation were associated positively with adult children’s estate planning, and discussed the relationships based on the family decision-making theory. DeBoer and Hoang (2017) indicated that intergenerational asset transfer is intentional rather than accidental and found a positive association between the receipt of an inheritance and the expectation of leaving a bequest, and this relationship was not affected by changes in estate tax policy. Lastly, Choi and Wilmarth (2019) found that depression was negatively, but financial assets were positively, associated with middle-aged and older people’s bequest expectation.

Sixth, the following three studies analyzed financial risk tolerance. Yao and Curl (2011) found a positive association between risk tolerance and market returns. West and Worthington (2014) discussed financial risk attitude based on regret theory associated with holding securities and found that higher levels of education, wealth, good health, and being self-employed were associated positively with Australians’ risk tolerance. They also found that there was a decreased pattern in risk tolerance over time and macroeconomic factors were still significant indicators of financial risk attitudes, but the marginal effects were smaller than individuals’ demographic and socioeconomic factors. Park and Yao (2016) discussed the consistency between risk attitude and behavior based on the expected utility theory and found that respondents who used a financial planner were more likely to have a consistent attitude and behavior.

Seventh, in addition to the studies discussed above, Gillen and Kim (2014) discussed the Big-Five personality traits as major determinants of financial help-seeking behavior based on the life cycle theory and psychological benefits and cost framework and found a positive relation between receipt of financial help-seeking and agreeableness and neuroticism, but a negative relation with conscientiousness. Grable and Watkins (2016) found the opportunity cost stamp collectors incurred was relatively large over time and regardless of the risk profile of the average stamp collector, the opportunity cost was associated with their collecting decision.

Discussion and Implications

In this study, we reviewed 33 selected research articles on financial behavior published in the JFEI over a decade (2010–2019) and explored both the articles’ conceptual and methodological trends with a content analysis approach. We provide a useful overview of the trends in financial behavior studies during the past decade using keywords, research methods, analytic datasets, and geographic location. Our results showed that “savings,” “wealth,” and “family issues” were the topics the articles discussed most frequently. All 33 articles were based on quantitative analysis and most (90.9%) conducted regression and regression-like analysis. The Health Retirement Study (HRS) and the Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF) were the secondary datasets used most widely in the studies selected. Although the majority of the studies (72.6%) analyzed financial behavior of Americans or US households by US-based authors, some US-based researchers collaborated with non-US researchers or worked on non-US data. Researchers around the globe, including Europe, Asia, Africa, and Australia, also discussed non-US financial behaviors.

Further, we reviewed suggestions for future studies that the authors of the selected studies mentioned, which can be summarized as follows. Firstly, many studies indicated that their findings can be extended or analyzed further using different types of research designs, such as longitudinal data (e.g., addressing/avoiding endogeneity, causality, omitted variables, noise issues) or experimental designs and by improving measurement’s sophistication and justification (e.g., using measures beyond self-reported responses or diversifying measures). Secondly, they suggested that future studies should expand the research topics and populations to encompass diverse circumstances of individual and household financial behavior by diversifying variables, measurement, and analytic samples, which could solidify and help generalize their research findings. Thirdly, research findings should provide practical implications to individuals and households so that they can improve their understanding of their behavior and decisions.

The major findings of this study provide a comprehensive portrait of financial behavior research published in the JFEI. This study offers some useful recommendations for future researchers in the next decade, as follows. First, researchers need to examine more varied financial behaviors rooted in the JFEI’s goals and scope. Some research areas in personal finance or family economics, such as savings, wealth, and financial planning, have gained popularity in the past decade and have strengthened the foundations of research in these areas. We expect that these areas will continue to be investigated with more practical applications that will help improve individuals and households’ financial behavior in the next decade. In particular, future research can delve into topics in the changing dynamics of family and social issues and analyze research topics with increased diversity (e.g., ethnicity/race, gender, education, age, international/cross-country studies) so that more populations can benefit from such research.

Second, we found that researchers have applied various analytic models to investigate financial behavior of individuals or households. However, no qualitative research methods that supplement quantitative research, or non-empirical research that covers content analysis or conceptual modeling, were found in the articles selected. Despite the novelty of the research questions and application of solid modeling, most research used a quantitative approach and, in particular, OLS and logistic regression models with secondary datasets. Although there are great advantages of using a secondary dataset to analyze financial behavior, such as reliability, completeness, and validity of the data, other research designs, such as experiments, focus groups, interviews, or primary survey collection, could capture some behavioral characteristics (e.g., attitudes and behavioral intentions) better. Future studies can apply various research designs, such as a mixed method of quantitative and qualitative approaches, which can supplement each other. Further, more complex and comprehensive research models, beyond regression or regression-like analyses, such as OLS and logistic regression models that can address behavioral dynamics, might be useful.

Third, many studies have identified financial behavior empirically as a determinant of, or related to, various factors, and emphasized the application of research findings to practices in their discussion and implications. Although it has been suggested widely that potential behavioral correction can be fulfilled through educational and clinical programs, a direct measure of behavioral changes or the effect of their implementation has not been documented well. Future studies can address the close association between consumer financial behavior and wide application in practice. Studies can substantiate the behavioral effects of the financial counseling, planning, and education programs and services discussed in previous studies by focusing on particular programs with various research methods to examine their relation with changes in individuals and households’ financial behavior and decision-making over time.

Fourth, we found that the studies used various theories and conceptual frameworks to examine financial behaviors of consumers; however, it should be noted that financial behavior is not a static concept and changes over time within an individual or household and interacts with the environment (e.g., Baker et al. 2005). To encompass the dynamics and underlying interactions with the environment and other factors, multidimensional aspects of behavior and their nature can be incorporated in future research. For example, application of the diverse theories and frameworks from transformative perspectives can expand the discussion of financial behaviors. Future studies that discuss various consumer financial behaviors and issues should expand their discussion to broader domains.

Fifth, studies on financial behaviors can offer general policy implications and provoke detailed policy discussion to increase consumer welfare in society. Studies have suggested not only that attention needs to be given to consumer issues, but also domain-specific program support and policy changes. For example, it is expected that financial literacy programs and initiatives in educational systems, public assistance programs that target financially and socially vulnerable populations (e.g., Gillen and Kim 2014), or asset building policies for non-asset poor positioned households (e.g., Leonard and Di 2014), can improve individuals’ financial behaviors (e.g., Griesdorn and Durband 2016). Extending the previous discussions about consumer financial behaviors requires an advanced focus on consumer welfare policy, as well as empirical tests and conceptual discussions on the way the policy programs worked. Thus, future studies should improve the connection between public policy and financial behaviors.

Sixth, a majority of studies were confined to individuals or households’ financial behavior in the US. Global financial markets and the transformation of technology have accelerated the interdependence and connectedness of financial consumers and reshaped consumer experiences, leading to evolving financial behaviors and issues. As noted in the international studies analyzed (e.g., Moreno-Herrero et al. 2017), work on global financial behaviors can help increase social awareness of important financial behaviors (e.g., retirement savings) and provide future policy implications (e.g., public pension programs) that differ across countries. It is expected that research on more diverse populations around the world will increase the readership of the JFEI and contribute to the study of overarching consumer issues in past, current, and future financial behavior. Instances of behavioral issues in consumer finance and economics are not limited to topics in the past decade (e.g., financial knowledge and wellbeing) but include emerging or under-studied topics in family resource management, the household division of labor and productivity, relations between economic and non-economic decisions, and the interrelation of work and family life.

In conclusion, the findings of this review will serve a greater population of researchers, educators, practitioners, and policymakers for the next decade. Financial behavior research and related areas have become increasingly important, so we encourage many researchers to consider these issues for their future studies.

References

Baker, S. M., Gentry, J. W., & Rittenburg, T. L. (2005). Building understanding of the domain of consumer vulnerability. Journal of Macromarketing, 25(2), 128–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146705280622.

Camões, F., & Vale, S. (2018). Housing valuation, wealth perception, and homeowners’ portfolio composition. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 39(3), 494–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-9570-y.

Cheung, C. H., & Yilmazer, T. (2019). Wealth management while dealing with memory loss. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(3), 470–485. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09610-w.

Choi, S., & Wilmarth, M. J. (2019). The moderating role of depressive symptoms between financial assets and bequests expectation. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(3), 498–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09621-7.

Collins, J. M. (2011). Mortgage mistakes? Demographic factors associated with problematic loan application behaviors. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9276-x.

Copur, Z., & Gutter, M. S. (2019). Economic, sociological, and psychological factors of the saving behavior: Turkey case. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(2), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-018-09606-y.

DeBoer, D. R., & Hoang, E. C. (2017). Inheritances and bequest planning: Evidence from the Survey of Consumer Finances. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 38(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-016-9509-0.

Dew, J. (2011). The association between consumer debt and the likelihood of divorce. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 554–565. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9274-z.

Duh, H. I., Benmoyal-Bouzaglo, S., Moschis, G. P., & Samaoui, L. (2015). Examination of young adults’ materialism in France and South Africa using two life-course theoretical perspectives. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36(2), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9400-9.

Fisher, P. J. (2013). Is there evidence of loss aversion in saving behaviors in Spain? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 34(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-012-9290-7.

Fisher, P. J., & Montalto, C. P. (2011). Loss aversion and saving behavior: Evidence from the 2007 U.S. Survey of Consumer Finances. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(1), 4–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9196-1.

Fontes, A. (2011). Differences in the likelihood of ownership of retirement saving assets by the foreign and native-born. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 612–624. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9262-3.

Gillen, M., & Kim, H. (2014). Older adults’ receipt of financial help: Does personality matter? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(2), 178–189. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9365-0.

Grable, J. E., & Watkins, K. (2016). Quantifying the value of collecting: Implications for financial advisers. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 37(4), 639–648. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-015-9471-2.

Griesdorn, T. S., & Durband, D. B. (2016). Does self-control predict wealth creation among young baby boomers? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 371(1), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-015-.

Haron, S. A., Sharpe, D. L., Abdel-Ghany, M., & Masud, J. (2013). Moving up the savings hierarchy: Examining savings motives of older Malay Muslim. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 34(3), 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-012-9333-0.

James, R. N., III, & Cude, B. J. (2009). Trends in Journal of Consumer Affairs feature articles: 1967–2007. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 43(1), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.2008.01131.x.

Ji, H., Hanna, S. D., Lawrence, F. C., & Miller, R. (2010). Two decades of the Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 21(1), 3–13.

Kim, E. J., Hanna, S. D., Chatterjee, S., & Lindamood, S. (2012). Who among the elderly owns stocks? The role of cognitive ability and bequest motive. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33(3), 338–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-012-9295-2.

Kim, J., La Taillade, J., & Kim, H. (2011). Family processes and adolescents’ financial behaviors. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 668–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9270-3.

Lee, S., Lee, J., & Chang, Y. (2014). Is dual income costly for married couples? An analysis of household expenditures. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9364-1.

Leonard, T., & Di, W. (2014). Is household wealth sustainable? An examination of asset poverty reentry after an exit. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9357-0.

Levinger, B., Benton, M., & Meier, S. (2011). The cost of not knowing the score: Self-estimated credit scores and financial outcomes. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 566–585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9273-0.

Lown, J. M., Kim, J., Gutter, M. S., & Hunt, A. T. (2015). Self-efficacy and savings among middle and low income households. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36(4), 491–502. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9419-y.

Manly, C. A., Wells, R. S., & Bettencourt, G. M. (2017). Financial planning for college: Parental preparation and capital conversion. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 38(3), 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-016-9517-0.

Marsden, M., Zick, C. D., & Mayer, R. N. (2011). The value of seeking financial advice. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(4), 625–643. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-011-9258-z.

McGregor, S. L. (2007). International journal of consumer studies: Decade review (1997–2006). International Journal of Consumer Studies, 31(1), 2–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1470-6431.2006.00566.x.

Moreno-Herrero, D., Salas-Velasco, M., & Sánchez-Campillo, J. (2017). Individual pension plans in Spain: How expected change in future income and liquidity constraints shape the behavior of households. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 38(4), 596–613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-017-9526-7.

Park, E., & Yao, R. (2016). Financial risk attitude and behavior: Do planners help increase consistency? Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 37(4), 624–638. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-015-9469-9.

Pastrapa, E., & Apostolopoulos, C. (2015). Estimating determinants of borrowing: Evidence from Greece. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9393-4.

Smith, H. L., Finke, M. S., & Huston, S. J. (2012). Financial sophistication and housing leverage among older households. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 33(3), 315–327. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-012-9293-4.

Totenhagen, C. J., Wilmarth, M. J., Serido, J., Curran, M. A., & Shim, S. (2019). Pathways from financial knowledge to relationship satisfaction: The roles of financial behaviors, perceived shared financial values with the romantic partner, and debt. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 40(3), 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-019-09611-9.

West, T., & Worthington, A. C. (2014). Macroeconomic conditions and Australian financial risk attitudes, 2001–2010. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 35(2), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-013-9362-3.

Whitaker, E. A., Bokemeiner, J. L., & Loveridge, S. (2013). Interactional associations of gender on savings behavior: Showing gender’s continued influence on economic action. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 34(1), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-012-9307-2.

Woosley, A., Danes, S. M., & Stum, M. J. (2017). Utilizing a family decision-making lens to examine adults’ end-of-life planning actions. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 38(1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-016-9497-0.

Xiao, J. J. (2008). Applying behavior theories to financial behavior. In J. J. Xiao (Ed.), Handbook of consumer finance research (pp. 69–81). New York: Springer.

Yao, R., & Curl, A. L. (2011). Do market returns influence risk tolerance? Evidence from panel data. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 32(3), 532–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-010-9223-2.

Yao, R., Xiao, J. J., & Liao, L. (2015). Effects of age on saving motives of Chinese urban consumers. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 36(2), 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-014-9395-2.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human and Animal Participants

This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This is one of several papers published together in Journal of Family and Economic Issues on the “Special Issue on Virtual Decade in Review”.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, K.T., Lee, J.M. A Review of a Decade of Financial Behavior Research in the Journal of Family and Economic Issues. J Fam Econ Iss 42 (Suppl 1), 131–141 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09711-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-020-09711-x