Abstract

There is sound evidence that increased level of peer support is linked negatively with youth vulnerably to internalizing and externalizing problems. Conversely, victimization by peers is associated positively with youth adjustment difficulties. The current study examines the mediating role of victimization in the association between classmates’ support and internalizing and externalizing behaviors, and the moderating role of gender in that association. The study is based on a sample of 243 7th grade Canadian adolescents. The results show that classmates’ support has a unique contribution to reduced adolescents’ internalizing behaviors above and beyond the effects of parental and teachers’ support. This association was partially mediated by youth victimization. Classmates’ support was a stronger predictor of internalizing behaviors among females compared to males. With respect to externalizing behaviors, the results indicated that while classmates’ support has no direct association with that outcome, parental support plays a central role in predicting externalizing behaviors. The association between classmates’ support and externalizing behavior was fully mediated by youth victimization. The current study highlights the importance of support by peers, with whom they interact on a regular basis, to adolescents’ well-being and functioning. The results also indicate that parents are still significant figures in adolescents’ lives. Those facts should be taken into account when intervening with young people.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Social support plays a key factor in young people’s lives (Davidson and Demaray 2007). Commonly defined as the “perceived support and regard which significant others manifest towards the self” (Harter 2012, p. 1), social support has been found to positively affect children and youth’s developmental outcomes and wellbeing (Cook et al. 2002; Davidson and Demaray 2007; Demaray and Malecki 2002a, b; Jackson and Warren 2000). Furthermore, support is negatively correlated with internalizing symptoms, such as anxiety, depression, and withdrawal (Demaray and Malecki 2002b; Herman-Stahl and Petersen 1996; McFarlane et al. 1995; White et al. 1998) as well as externalizing behaviors such as aggression, acting out and conduct problems (Mishna et al. 2016; Wight et al. 2006; Walden and Beran 2010).

Current research on the links between social support and youth outcomes has explored a range of sources of support, mainly including parent-child relationships, peer support, and support within the school environment. It was found that supportive relationships with parents are related to children and youth’s increased wellbeing and global self-esteem (Laible et al. 2004; Ross and Broh 2000), and to reduced levels of depression and anxiety (Rueger et al. 2010; Wills et al. 2004). Furthermore, parental support and warmth were found to protect adolescents from both bullying victimization (Haynie et al. 2001) and perpetration (Bowers et al. 1994).

In addition to parental support, research has highlighted the importance of teacher support in the lives of young people, due to the considerable time spent at school. Supportive relationships with teachers are associated with children’s positive self-concept (Demaray et al. 2009) and with lower levels of traditional physical and verbal peer victimization (Furlong et al. 1995; Khoury-Kassabri et al. 2004).

Adolescence involves various transitions that may modify youth’s relationships with some of their central sources of support. Specifically, adolescents tend to lessen their dependence on adults while increasing their reliance on their friends. Support from one’s peer group becomes vital in adolescence; young people tend to talk and to seek emotional, instrumental and other forms of support, such as advice, from friends (Bokhorst et al. 2010; Collins and Laursen 2004; Scholte and Van Aken 2006). Some studies indicate that friends are perceived as more salient sources of support than parents during adolescence (e.g., Furman and Buhrmester 1992), while others found no significant difference between levels of support by parents and peers (e.g., Helsen et al. 2000).

There is accumulating evidence that peer support is negatively associated with internalizing behaviors (Demaray and Malecki 2002a; Kendrick et al. 2012; Licitra-Kleckler and Waas 1993; Newman et al. 2007). For instance, in their study of approximately six hundred adolescents, Rueger et al. (2010) found that perceived peer social support was associated with lower levels of depression and anxiety. This association may be explained by the main-effect model (Cohen and Wills 1985), arguing that social support has a positive benefit for all children. This model assumes that access to social support reduces psychological problems by providing the individual with helpful information and improving their sense of worth, belonging, and security. In a study of approximately one thousand high school students in the US, however, Windle (1992) found that friends’ support was not associated with levels of depression.

Studies examining the association between peer support and externalizing behaviors similarly reported conflicting results. Kendrick et al. (2012), for example, found that higher levels of peer support were related to decreased bullying (see also, Holt and Espelage 2007; Walden and Beran 2010). A similar trend was reported with respect to delinquent behaviors (Mcelhaney et al. 2006). Meadows (2007), in contrast, found that peer support was positively related to both minor and major offending (Razzino et al. 2004; Windle 1992). Nonetheless, in the latter research, and in studies showing a similar pattern, peer relations typically served as a risk factor when the peer group comprised delinquent peers (see, for review and further discussion: Meadows 2007).

This association between increased peer support and reduced levels of externalizing behaviors may be explained by the Primary Socialization Theory (Higgins et al. 2010) which posits that behaviors are socially learned, and that during adolescence peer groups play a major role in affecting prosocial and delinquent behaviors. Youth with weak bonds and low-quality friendships will be more likely to connect with deviant peers, while adolescents with strong and high-quality friendships will be less associated with antisocial peers and, in turn, less involved in violence and delinquency (Dishion et al. 2004).

The literature indicates the need to take into account gender when examining peer support. Studies consistently show that females’ perceptions of peer support are higher than males’ (Helsen et al. 2000; Kendrick et al. 2012; Demaray and Malecki 2003; Rueger et al. 2010; Tanigawa et al. 2011). Nonetheless, the differences between boys and girls in the way that social support buffers emotional and behavioral difficulties, in the face of adversities, are inconsistent.

In their study, Rueger et al. (2010), found that greater classmate support was a significant predictor of reduced internalizing behavior (i.e., levels of anxiety and depression), for boys but not for girls. This association was above and beyond the effects of other sources of support, such as from parents, teachers, and close friends (also see Davidson and Demaray 2007). On the other hand, a study by Schmidt and Bagwell (2007) found that having a close friendship acted as a buffer against depressive symptoms in the face of direct peer victimization for girls, but not for boys. Similar inconsistencies have been reported with respect to externalizing behaviors. Kendrick et al. (2012), for instance, found that increased support by friends was associated with reduced bullying perpetration 1 year later for boys but not for girls. In contrast, other studies found positive associations between peer support and delinquency for boys but not for girls (e.g., Licitra-Kleckler and Waas 1993). These inconsistent findings emphasize the need for further examination of the role of gender in the associations between peer support and youth outcomes.

Peer victimization is a phenomenon of worldwide concern (see, Sullivan Wilcox and Ousey 2011; DeVoe and Murphy 2011), which might have a moderating effect in the link between peer support and youth functioning. In Canada, for example, according to the Canadian National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth, 12% of children are bullied at school and 7% are bullied on the way to and from school (see: Mishna and Van Wert 2015). The Health Behaviour in School-Age Children (HBSC) survey is a cyclical study that obtains information about a number of issues, including bullying, from young people in countries around the world. According to the 1993/1994 cycle in Canada, approximately 34% of boys and 27% of girls reported experiencing victimization occasionally and 42% of boys and 28% of girls reported bullying others occasionally. In the 2005/2006 cycle, the prevalence of occasional bullying among Canadian boys and girls had not decreased; 36% of boys and 35% of girls reported experiencing occasional victimization and 42% of boys and 34% of girls reported occasionally bullying others. Overall, these findings reflect a steady prevalence of bullying over time (Mishna et al. 2010).

Although considerable research has examined the association between support, victimization and internalizing and externalizing behavior, few studies have explored the mechanisms underlying the effects of social support on such outcomes and the role that peer victimization might play in that process. With respect to peer support and victimization, peer friendships and relationships play a significant role in bullying involvement during childhood and adolescence (Espelage and Swearer 2011; Raskauskas and Stoltz 2007). Research has identified peer acceptance as a protective factor against peer victimization (Demaray and Malecki 2003), and studies have found an association between positive friendships and lower levels of victimization (Bollmer et al. 2005; Schmidt and Bagwell 2007). Victims of bullying tend to have fewer friends and they are more rejected by their peers at school (Hodges et al. 1999).

This association may be explained by the Friendship Protection Hypothesis (Boulton et al. 1999). According to this hypothesis, high quality friendships (i.e., lower conflict and more support from friends) may decrease victimization because such friendships increase coping strategies, and as a result, may lessen vulnerability to victimization (Kendrick et al. 2012).

There is enormous empirical evidence that victimization by peers has detrimental effects on both the short- and long-term well-being of victims. Victimized children were found to be more vulnerable to many types of psychological difficulties and distress (Coie et al. 1992; Khoury-Kassabri et al. 2004; Mishna 2012; Schwartz et al. 2006). They experience higher levels of internalizing difficulties, such as depression and anxiety, tend to report more loneliness and lower self-esteem, as well as increased withdrawal and isolation, compared with non-victimized young people (Beaty and Alexeyev 2008; Bond et al. 2001; Demaray and Malecki 2002a; Hawker and Boulton 2000; Tanigawa et al. 2011; Ttofi et al. 2011). Victimized children reported skipping school more often than non-victimized peers (Khoury-Kassabri 2012). Victimization by peers may, in addition, lead to externalizing behaviors such as violence and delinquency (Gorman-Smith et al. 2004; Massarwi and Khoury-Kassabri 2017). A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies found that, over time, peer victimization significantly predicted increases in both internalizing and externalizing problems (Reijntjes et al. 2011).

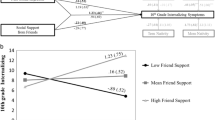

Based on the existing research, perceived peer support might have a direct impact on externalizing and internalizing behavior (Demaray and Malecki 2002a; Demaray et al. 2009; Rueger et al. 2010; Wills et al. 2004). Alternatively, the association between peer support and youth outcomes may be indirect; students with high levels of perceived peer support may be less likely to be victimized by others which, in turn, may predict lower levels of internalizing and externalizing difficulties (Wentzel 1998; Wentzel et al. 1990). The current study examined the mediating role of peer victimization (being physically, verbally, or socially bullied by another student) in the link between perceived classmates’ social support and adolescent internalizing and externalizing behaviors; in addition, the study examined the moderating role of gender in the association between perceived classmates’ social support and internalizing and externalizing behaviors. (see Fig. 1).

The first research hypothesis in the current study was that perceived classmates’ social support would be negatively correlated with externalizing and internalizing behaviors and with experiences of peer victimization. It was further hypothesized that bullying victimization experiences would be positively correlated with adolescent externalizing and internalizing behaviors. The main aims of the study were to examine the hypothesis that bullying victimization experiences would mediate the association between perceived classmates’ social support and adolescent internalizing and externalizing behaviors; and the hypothesis that gender would moderate the association between perceived classmates’ social support and internalizing and externalizing behaviors. More specifically, it was hypothesized that the link between social support and externalizing and internalizing problems would be stronger among girls than boys.

Method

Participants

This study is part of a large-scale study on traditional and cyber bullying among students in fourth, seventh and tenth grades. Schools were stratified into three categories of need (low, medium, and high) based on an index developed by the school board through which schools were ranked on external challenges to student achievement. Neighborhood-level census data, used to develop the index, included income and education levels, ratio of households receiving social assistance, and ratio of single-parent families (Toronto District School Board 2014). This sample stratification ensured representation of ethno-cultural and socioeconomic diversity. Of the 62 schools that were invited to participate, 19 agreed, which was a school participation rate of 31%. The main reason principals gave for declining to have their schools participate was an overload of research. Of the 3873 students invited to participate, 691 agreed. Twenty-two student participants withdrew, resulting in 669 student participants and a response rate of 17.3% during year one of the study. We attribute this relatively low response rate to the active consent process. The sample demographics are ethnically representative and resemble the population in gender distribution and in terms of those whose primary language was not English (Toronto District School Board 2014; Mishna et al. 2016). The current article focuses on the 243 adolescents in grade 7 (60.1% females), because the variables examined in the current study were not part of questionnaires for grades 4 and 10.

Procedure

Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Toronto Research Ethics Board and from the External Research Review Committee at the partnering school board. Consent to participate in the study was obtained actively and, with approval of the school board, passively in years two and three. Research assistants visited grades in the 19 participating schools to explain the study and distribute consent forms. Parental/guardian consent was obtained for their child to participate, if they were interested in participating themselves, and/or if they consented to the research team asking their child’s teacher to participate. Once parental consent was obtained, teachers were invited to participate.

In anticipation that some questions could lead to distress or disclosure of information of a potentially sensitive or distressing nature, a protocol approved by both the University’s Research Ethics Board and the School Board’s External Research Review Committee, was established to identify and assist students categorized as in distress. All children and youth identified as in distress were interviewed individually in a private school setting by a clinically trained research assistant, who was a Master of Social Work student or who possessed equivalent education and experience (Mishna et al. 2014). When warranted, participants were connected to appropriate services within the school board.

Measures

Adolescents completed self-report questionnaires. In this article we focus on the students’ demographics and on measures capturing traditional bullying experiences, social support, and internalizing and externalizing behaviors, as specified below.

Internalizing and externalizing behaviors

The measures of externalizing and internalizing behavior problems in the current study have been well-used and determined to be reliable and valid (Achenbach 1991, The Youth Self-Report). The Internalizing scale comprises 31 items referring to three patterns: withdrawal, somatic complaints, and anxiety/depression. The externalizing sub-scale includes 32 items referring to two patterns: delinquent behavior and aggressive behavior. Each item is scored as follows: 0 = not true, 1 = somewhat or sometimes true, and 2 = very true or often true and refers to the adolescents’ evaluation of such behavior in the previous 6 months. The measure of each sub-scale is based on the summation of the scores of the items included in the sub-scale. The internalizing sub-scale score, therefore, ranges from 0 to 62 and the score for externalizing behavior problems ranges from 0 to 64. It should be noted that the data were coded in such a way that only the summative raw score for these sub-scales are documented; therefore, internal consistency could not be examined in this investigation.

Bullying victimization experiences

To measure children’s experiences of bullying victimization, a questionnaire was developed building on the authors’ previous research and on the literature (Mishna et al. 2010; Mishna et al. 2009; Olweus 2012; Pepler et al. 1993). Respondents were asked how frequently they had been physically (e.g., hit, pushed, shoved, slapped, kicked, spit at, beaten up), verbally (e.g., called names, insulted, threatened) and socially (e.g., excluded, gossiped about, rumors spread) bullied in the previous 30 days. Student participants responded to each type of victimization on the following Likert-type scale: 1 = never, 2 = once or twice, 3 = three to four times, 4 = every day. A principal component exploratory factor analysis showed that all three victimization items are loaded on a single factor (eigenvalue = 2.10, accounting for 70.14% of the variance, loadings ranging from .70 to .90). A composite bullying victimization measure (α = .806) was therefore created by assigning one point for each specific behavior the adolescent had experienced at least once; the summative score, hence ranges from 0 (no bullying victimization experiences) to 3 (at least three types of bullying victimization experiences).

Social support

The Social Support Scale for Children (SSCC; Harter 1985) assesses children’s support systems. We used three sub-scales, each comprising 6 items, reflecting three major domains of support in the lives of youth, derived from the SSCC: (a) classmates’ support (α = .85) (e.g., “Some kids have classmates who sometimes make fun of them BUT other kids don’t have classmates who make fun of them”); (b) parental support (α = .85) (e.g., “Some kids have parents who don’t really understand them BUT other kids have parents who really do understand”); and (c) teacher support (α = .84) (e.g., “Some kids don’t have a teacher who helps them to do their very best BUT other kids do have a teacher who helps them to do their very best”). For each question, the student was, first, asked to decide which kind of child is most like him or her, the one described in the first part of the statement or the one described in the second part of the statement. Then they were asked to indicate whether for the statement they chose, it is sort of true or really true for them. For each statement, we recoded the scale to range from 1 (really true for me) or 2 (sort of true for me) when one of the options of the first part of the statement was chosen, and 3 (sort of true for me) or 4 (really true for me) in case the second part of the statement was chosen. Each support scale was calculated based on the mean of items included in it, and ranges, therefore, from 1 (low level of support) to 4 (high level of support). In this study, classmates’ social support served as an independent variable and teacher and parental support served as co-variates in the research model.

Socio-demographic characteristics

Adolescents were asked to report on their gender, academic achievements (scaled from “Mostly A’s” to “Mostly D’s”), and parental education (on a scale ranging from 1 = High school to 3 = University).

Data Analyses

We first examined the descriptive statistics related to students’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors and the study’s independent, mediating, moderating, and control variables. Second, bivariate analyses were conducted to test the relationships among students’ internalizing and externalizing behaviors and the mediating, moderating, and control variables using Pearson correlations. The correlations among all other variables were also tested (Table 1). Third, we tested the mediating role of experiencing bullying victimization on the relationship between classmates’ social support and youth’s internalizing and externalizing behaviors through traditional victimization, and the moderating role of gender on the association between classmates’ support and internalizing and externalizing behaviors. To do so, we used a Moderated-Mediation Model examined through PROCESS analysis using SPSS (Model #5; Preacher and Hayes 2008). In that model, the 95% confidence interval obtained with 5000 bootstrap resamples was used (Preacher and Hayes 2008). Once a bootstrap sample of the original data is generated, the regression coefficients for the statistical model are estimated. This procedure yields an upper and lower bound - confidence interval - on the likely value of the indirect effect (Hayes 2013). The model controlled for factors found in the bivariate analyses as significantly associated with internalizing and externalizing behaviors (parental and teacher support; see Table 1). We controlled for students’ academic achievements and parental education as they were found to be associated with the factors included in the model (Danielsen et al. 2009; Demaray and Malecki 2003; Mishna et al. 2016).

Results

Most of the students in the study reported receiving school grades that were A’s (40.8%) or B’s (51.7%), with only 2.1% of the students reported receiving C’s. The majority of their parents have completed a university degree (mothers: 64.4%; fathers: 74.6%), whereas, as reported by the youth, only 18.1% of the mothers and 12.4% of the fathers have a high school education.

One in four students (25.1%) reported having experienced a minimum of one type of bullying victimization at least once during the previous month. Of those, 7.8% experienced at least one bullying type, 11.9% experienced at least two and 5.3% experienced three bullying types. Students’ reports of their social support were relatively high. On a scale ranging from 1 (low level support) to 4 (high level of support), the average of perceived parental support was 3.48 (SD = 0.62); followed by an average of 3.33 of teacher support (SD = 0.63); and classmates’ support (M = 3.21, SD = 0.61). Repeated measures analysis revealed that there is a significant difference in adolescents’ perceptions of the three support sources (F (232, 2) = 21.81, p < 0.001). Paired sample t-tests indicated that parental support is significantly higher than classmates’ (t (232) = 6.50, p < .001) and teachers’ support (t (232) = 3.74, p < .001), with the latter significantly higher than classmates’ support (t (232) = 2.80, p < .01). On a scale ranging from 0 to 62, the mean of children’s reports on internalizing behavior was 11.21 (SD = 10.43). The mean for externalizing behavior was 7.71 (SD = 6.73) on a scale ranging from 0 to 64.

We examined the relationship among the study’s variables. As shown in Table 1, girls reported significantly more internalizing behaviors than males. Surprisingly, no gender differences were found with respect to externalizing behaviors. Consistent with our hypotheses, children’s reports of social support by parents, teachers, and classmates were significantly and positively associated with both internalizing and externalizing behaviors and negatively correlated with students’ bullying experiences. Furthermore, as hypothesized, bullying victimization was significantly and positively associated with students’ reports of internalizing and externalizing behaviors. No significant association was found between students’ academic achievements and parental education level and each of the internalizing and externalizing behaviors.

In addition, the results in Table 1 show, that the more the students reported internalizing behaviors, the more likely they were to report displaying externalizing behaviors. Furthermore, the results in Table 1 show that females’ perception of teachers’ support is significantly higher than males’ perception, while no significant differences between males and females were found with respect to perceived parental and classmates’ support.

In this study, we utilized mediated-moderation models to explain the variance in both internalizing and externalizing behaviors among youth (see Fig. 1). The models explored whether the associations between classmates’ support and internalizing and externalizing behaviors, are mediated by students’ bullying experiences, and whether gender moderates the relationship between classmates’ support and the outcome variables.

In line with our hypothesis, classmates’ support was significantly and negatively associated with the mediating factor – bullying victimization (B = −0.47, SE = 0.10, p < .001). The greater the students’ perception of receiving support from their classmates, the lower their exposure to traditional bullying victimization.

The results show that after including the control variables (parental and teacher support) in the regression equation, as hypothesized, perceived classmate social support was found to have an indirect effect on internalizing behaviors through bullying victimization (B = −.92, SE = 0.43), with a bootstrapped 95% CI around the indirect effect (BootLICI = −1.95, BootULCI = −.23). As reported in Table 2, the direct effect of social support by classmates on students’ internalizing behavior remained significant after including the mediating factor, thus suggesting partial mediation.

Similarly, as expected, our results suggest that bullying victimization mediated the association between classmate social support and students’ externalizing behavior (B = −.57, SE = .28, BootLICI = −1.22, BootULCI = −.10). Contrary to our hypothesis, the results in Table 2 show that the association between classmates’ social support and students’ externalizing behavior is not significant, indicating that the association between these two factors is fully mediated by students’ experiences of bullying victimization.

Our model also examined the moderating effect that gender has on the relationship between classmates’ support and internalizing/externalizing behavior. The results, presented in Table 2, are consistent with our hypothesis showing that gender significantly moderates the association between social support from classmates and internalizing behavior; the moderation effect of gender, however, was insignificant regarding externalizing behaviors. As shown in Fig. 2, the association between classmates’ support and internalizing behavior, was, as expected, stronger among girls (B = −7.89, SE = 1.34, p < .001) compared with boys (B = −3.72, SE = 1.56, p < .05). The model explained 35% of the variance in students’ internalizing behaviors and 23% of the variance in students’ externalizing behavior.

Discussion

The current study focused on the contributions of classmates’ support to youth adjustment difficulties and by examining the mediating role of victimization and the moderating role of gender on that association, among 243 7th grade Canadian adolescents. The examination of the research model among adolescents is of special interest in light of the changes youth experience during adolescence including increased independence from adults and increased reliance on peers. As, during that period, support received from the peer group becomes significantly important (Bokhorst et al. 2010; Collins and Laursen 2004; Scholte and Van Aken 2006), one of the aims of the study was to explore whether classmate support during adolescence contributes to youth outcomes, above and beyond the effects of other significant support systems (i.e., parents and teachers).

Our results show relatively high levels of reported perceived support by the three sources that were examined. They show however, the highest perceived support received from parents and the lowest from classmates. This finding may show, that despite the possible decreased dependence on parents, they remain significant figures in adolescents’ lives and while classmate support is less significant than that of parents, it is still high and important (for similar findings, see also, Bokhorst et al. 2010; Helsen et al. 2000).

In addition, our results revealed that girls reported higher perceived teacher support compared with boys (Rueger et al. 2010; Wentzel 1998). No significant differences were found between boys’ and girls’ perceptions of parental support (Demaray and Malecki 2002a; Malecki and Demaray 2003; Rueger et al. 2010). Furthermore, contrary to some previous studies (Rueger et al. 2008, 2010; Wentzel 1998), we found that perceptions of classmate support were consistent across gender. In light of these findings, our study sought to explore whether classmate support buffers externalizing and internalizing behavior difficulties in a similar way for boys and girls.

Internalizing Behaviors: Support, Gender, and Victimization

Consistent with previous studies and with our hypotheses, we found that the stronger the perceived social support from various sources in adolescents’ lives (i.e., parents, teachers and classmates), the lower the adolescents’ reports of internalizing behaviors (Landman-Peeters et al. 2005; Rueger et al. 2008). We found that classmates’ support has a unique contribution to reduced adolescents’ internalizing behaviors above and beyond the effects of parental and teacher support (see also, Demaray and Malecki 2002a; Kendrick et al. 2012; Licitra-Kleckler and Waas 1993; Newman et al. 2007). Rueger et al. (2008) reported, similarly, that perceived support from a general peer group with whom adolescents interact on a regular basis (but not necessarily their close friends) was negatively related to their reports of internalizing behavior. The availability of supportive peers in adolescents’ lives possibly provides them with the feeling that there are others in their environment, in this case others that are in their same developmental phase, on whom they can rely when needed, which may decrease their emotional difficulties (Cohen and Wills 1985).

In line with the ample existing evidence in the field, we found that females have significantly more internalizing difficulties than males (Angold et al. 2002; Kolip 1997; Landman-Peeters et al. 2005; Lewinsohn et al. 1998; Wade et al. 2002). One of the common explanations for increased internalizing symptomatology among girls is linked with the significant role of socialization on girls’ self-regulation, increasing their vulnerability to internalizing problems, in the face of interpersonal concerns and reactivity to stressful life events involving others, compared with boys (Leadbeater et al. 1999). There is inconsistency in previous works, however, concerning the role of support for internalizing behaviors among adolescent boys and girls (Colarossi and Eccles 2003; Rueger et al. 2008). The results of the current study revealed that the relationship between classmates’ support and internalizing behavior was significantly negative for both males and females, but it was statistically significantly stronger for females (see also, Landman-Peeters et al. 2005; Schraedley et al. 1999). The observed gender differences found in our study might be explained in light of Gilligan’s (1982) work suggesting that girls tend to turn to their social support relations for psychological support, while boys turn more to instrumental support. It might be assumed, therefore, that females are more likely to benefit from the social support they receive from their classmates, especially with regards to internalizing difficulties, because psychological support is a central element in their coping.

Furthermore, the study’s results revealed that the association between teacher support and internalizing behavior turn insignificant when classmate and parental support are included in the model. The linkage between parental support and internalizing behaviors remained significant, however, after including all the predictor variables in the model. These findings support previous literature demonstrating that parental support continues to be important for boys and girls in adolescence, and continues to play a crucial role in the positive development and safety promotion of their adolescent children (Blum et al. 2003; Farrington 2005; Khoury-Kassabri et al. 2015; Massarwi, in press; Özbay and Özcan 2008; Rueger et al. 2008).

In addition to the direct effect of classmates’ support on adolescents’ internalizing behaviors, we aimed to explore whether this association is mediated by adolescents’ experiences of peer victimization. Two interesting results were revealed: first, consistent with our hypothesis, we found that victimized children were more vulnerable to internalizing problems (see also, Beaty and Alexeyev 2008; Bond et al. 2001; Demaray and Malecki 2002a; Hawker and Boulton 2000; Tanigawa et al. 2011; Ttofi et al. 2011). Second, as hypothesized, the negative association between adolescents’ perception of classmates’ support and internalizing difficulties was partially mediated by youth’s experience of peer victimization, after controlling for the effects of parental and teacher support. In other words, students with high levels of perceived classmates’ support were less likely to be victimized by others (Bollmer et al. 2005; Boulton et al. 1999; Demaray and Malecki 2003; Kendrick et al. 2012), which in turn, predicted lower levels of internalizing difficulties (Wentzel 1998; Wentzel et al. 1990). The findings indicating such significant partial mediation mean that classmates’ support still has a direct and significant effect on youth internalizing difficulties, after controlling for all other factors in the model, including peer victimization. This finding emphasizes once again the important role classmates play in promoting adolescents’ well-being, not only in cases of stressful interpersonal events but also in general. The availability of supportive peers, with whom the adolescent can talk, share and seek emotional and instrumental support possibly reduces psychological problems by providing the individual with helpful information and improving their sense of worth, belonging, and security (Bokhorst et al. 2010; Cohen and Wills 1985; Collins and Laursen 2004; Haber et al. 2007).

Externalizing Behaviors: The Role of Support and Peer Victimization

Our findings showed that despite sharing some similarities in their explanatory variables (such as classmates’ support), internalizing and externalizing behaviors are affected differently by some of the factors assessed in our model. The results revealed, first, that, similar to internalizing behaviors, youth’s externalizing behaviors were, as expected, significantly and positively associated with all support sources: parents (Bowers et al. 1994; Massarwi 2017; Massarwi and Khoury-Kassabri 2017); teachers (Khoury-Kassabri et al. 2004, 2009); and classmates (Holt and Espelage 2007; Kendrick et al. 2012; Walden and Beran 2010).

Contrary to our finding regarding internalizing behaviors, the association between classmates’ support and externalizing behaviors becomes insignificant after controlling for teachers’ support (their contribution to reduced externalization was statistically insignificant) and parental support (which was significantly related to externalization). This finding was consistent among males and females.

As indicated earlier, these results emphasize the significant role parents play in their adolescent children’s lives. Parental support was found to predict lower levels of youth involvement in externalizing behaviors. It is important in future studies to replicate the findings regarding the significant contribution of peer support to internalization vs. the insignificant contribution to externalization, above and beyond parental and teachers support. These results regarding parents’ contribution to decreased levels of externalizing behaviors may be explained by Hirschi’s Social Bond Theory (Hirschi 2002). According to Hirschi (1969), children who have close relationships with their parents, who have parental support and whose parents are involved in their lives, might be less involved in violence and delinquency, because they do not wish to jeopardize these important relationships and lose their parents’ love and respect (Khoury-Kassabri et al. 2015; Pickering and Vazsonyi 2010; Wong 2005).

In addition, the results show that the association between classmates’ support and youth externalizing behavior is indirect and fully mediated by youth victimization. Students with high levels of perceived peer support were less likely to be victimized by others (Bollmer et al. 2005; Boulton et al. 1999; Demaray and Malecki 2003; Kendrick et al. 2012), and reported less involvement in externalizing behaviors (Wentzel 1998).

This association might be interpreted by Boulton et al.’s (1999) Friendship Protection Hypothesis, according to which the quality of friendships may decrease victimization because it decreases vulnerability and increases coping strategies (Kendrick et al. 2012). These coping skills might be very effective in decreasing youth involvement in aggressive and delinquent behaviors. Although classmates’ support has no direct effect on externalizing behavior, it still has a central role in its negative contribution to peer victimization, which in turn, is associated with externalizing behaviors. Such findings help to elucidate variations in adolescents’ behaviors and the factors explaining such behaviors.

Limitations and Recommendations for Future Research

There are several limitations that need to be acknowledged. First, the study focused on seventh grade students and should be conducted with wider age group samples of adolescents. Moreover, this study relied exclusively on the adolescents’ reports. It would be beneficial in future studies to include other informants, such as teachers and parents. Future studies should include separate measures of instrumental and emotional support. The current study is based on a cross-sectional design which does not enable causal conclusions. Longitudinal research is required to further understand the role of social support on peer victimization and adolescents’ externalizing and internalizing behavior problems. Whereas the current study examined parents’ support as a whole, it would be important to differentiate the father’s and the mother’s support. Finally, it is recommended that future studies replicate the findings of the current study among adolescents from diverse cultures.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the youth self-report and 1991 profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

Angold, A., Erkanli, A., Silberg, J., Eaves, L., & Costello, E. J. (2002). Depression scale scores in 8–17-year-olds: Effects of age and gender. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 43, 1052–1063. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00232.

Beaty, L. A., & Alexeyev, E. B. (2008). The problem of school bullies: What the research tells us. Adolescence, 43, 1–11.

Blum, J., Ireland, M., & Blum, R. W. (2003). Gender differences in juvenile violence: A report from Add Health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 32, 234–240. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(02)00448-2.

Bokhorst, C. L., Sumter, S. R., & Westenberg, P. M. (2010). Social support from parents, friends, classmates, and teachers in children and adolescents aged 9 to 18 years: Who is perceived as most supportive? Social Development, 19, 417–426. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00540.x.

Bollmer, J. M., Milich, R., Harris, M. J., & Maras, M. A. (2005). A friend in need: The role of friendship quality as a protective factor in peer victimization and bullying. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 701–712. doi:10.1177/0886260504272897.

Bond, L., Carlin, J., Thomas, L., Rubin, K., & Patton, G. (2001). Does bullying cause emotional problems? A prospective study of young teenagers. British Medical Journal, 323, 480–484. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7311.480.

Boulton, M. J., Trueman, M., Chau, C., Whitehand, C., & Amatya, K. (1999). Concurrent and longitudinal links between friendship and peer victimization: Implications for befriending interventions. Journal of Adolescence, 22, 461–466. doi:10.1006/jado.1999.0240.

Bowers, L., Smith, P. K., & Binney, V. (1994). Perceived family relationships of bullies, victims and bully/victims in middle childhood. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 215–232.

Cohen, S., & Wills, T. (1985). Stress, social support, and the buffering hypothesis. Psychological Bulletin, 98, 310–357. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.2.310.

Coie, J. D., Lochman, J. E., Terry, R., & Hyman, C. (1992). Predicting early adolescent disorder from childhood aggression and peer rejection. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60, 783–792. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.60.5.783.

Colarossi, L. G., & Eccles, J. S. (2003). Differential effects of support providers on adolescents’ mental health. Social Work Research, 27, 19–30. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.60.5.783.

Collins, W. A., & Laursen, B. (2004). Changing relationships, changing youth: Interpersonal contexts of adolescent development. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 24(1), 55–62. doi:10.1177/0272431603260882.

Cook, T. D., Herman, M. R., Phillips, M., & Settersten, Jr, R. A. (2002). Some ways in which neighborhoods, nuclear families, friendship groups, and schools jointly affect changes in early adolescent development. Child Development, 73, 1283–1309. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00472.

Davidson, L. M., & Demaray, M. K. (2007). Social support as a moderator between victimization and internalizing-externalizing distress from bullying. School Psychology Review, 36, 383–405.

Demaray, M. K., & Malecki, C. K. (2002a). The relationship between perceived social support and maladjustment for students at risk. Psychology in the Schools, 39, 305–316. doi:10.1002/pits.10018.

Demaray, M. K., & Malecki, C. K. (2002b). Critical levels of perceived social support associated with student adjustment. School Psychology Quarterly, 17, 213–224. doi:10.1521/scpq.17.3.213.20883.

Demaray, M. K., & Malecki, C. K. (2003). Perceptions of the frequency and importance of social support by students classified as victims, bullies, and bully/victims in an urban middle school. School Psychology Review, 32, 471–489.

Demaray, M. K., Malecki, C. K., Rueger, S. Y., Brown, S. E., & Summers, K. H. (2009). The role of youth’s ratings of the importance of socially supportive behaviors in the relationship between social support and self-concept. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 13–28. doi:10.1007/s10964-007-9258-3.

Danielsen, A. G., Samdal, O., Hetland, J., & Wold, B. (2009). School-related social support and students’ perceived life satisfaction. Journal of Educational Research, 102, 303–320.

DeVoe, J., & Murphy, C. (2011). Student reports of bullying and cyber-bullying: Results from the 2009 school crime supplement to the national crime victimization survey: Web tables- NCES 2011-336. USA: National Center for Education Statistics.

Dishion, T. J., Nelson, S. E., Winter, C. E., & Bullock, B. M. (2004). Adolescent friendship as a dynamic system: Entropy and deviance in the etiology and course of male antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32, 651–663. doi:10.1023/B:JACP.0000047213.31812.21.

Espelage, D. L. & Swearer, S. M. (Eds.) (2011). Bullying in North American schools. New York, NY: Routledge.

Farrington, D. (2005). Childhood origins of antisocial behavior. Clinical psychology and psychotherapy, 12, 177–190. doi:10.1002/cpp.448.

Furlong, M. J., Chung, A., Bates, M., & Morrison, R. L. (1995). Who are the victims of school violence? A comparison of student non-victims and multi-victims. Education and Treatment of Children, 18, 282–298.

Furman, W., & Buhrmester, D. (1992). Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development, 63, 103–115. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Gorman-Smith, D., Henry, D. B., & Tolan, P. H. (2004). Exposure to community violence and violence perpetration: The protective effects of family functioning. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 439–449. doi:10.1207/s15374424jccp3303_2.

Haber, M. G., Cohen, J. L., & Lucas, T. (2007). The relationship between self-reported received and perceived social support: A meta-analytic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 39, 133–144. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9100-9.

Harter, S. (1985). Manual for the social support scale for children. Denver, CO: University of Denver.

Harter, S. (2012). The construction of the self: Developmental and sociocultural foundations. New York, NY: Guilford.

Hawker, D. S., & Boulton, M. J. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41, 441–455. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00629.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Haynie, D. L., Nansel, T., Eitel, P., Crump, A. D., Saylor, K., Yu, K., & Simons-Morton, B. (2001). Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups of at-risk youth. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 21, 29–49. doi:10.1177/0272431601021001002.

Helsen, M., Vollebergh, W., & Meeus, W. (2000). Social support from parents and friends and emotional problems in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 29, 319–335. doi:10.1023/A:1005147708827.

Herman-Stahl, M., & Petersen, A. C. (1996). The protective role of coping and social resources for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 25, 733–753. doi:10.1007/BF01537451.

Higgins, G. E., Ricketts, M. L., Marcum, C. D., & Mahoney, M. (2010). Primary socialization theory: An exploratory study of delinquent trajectories. Criminal Justice Studies: A Critical Journal of Crime, Law & Society, 23, 133–146. doi:10.1080/1478601X.2010.485472.

Hirschi, T. (1969). Causes of delinquency. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Hirschi, T. (2002). Causes of delinquency. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Hodges, E. V., Boivin, M., Vitaro, F., & Bukowski, W. M. (1999). The power of friendship: Protection against an escalating cycle of peer victimization. Developmental Psychology, 35, 94–101. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.94.

Holt, M. K., & Espelage, D. L. (2007). Perceived social support among bullies, victims, and bully-victims. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36, 984–994. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9153-3.

Jackson, Y., & Warren, J. S. (2000). Appraisal, social support, and life events: Predicting outcome behavior in school‐age children. Child Development, 71, 1441–1457. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00238.

Jones, S., Cauffman, E., & Piquero, A. R. (2007). The influence of parental support among incarcerated adolescent offenders: The moderating effects of self-control. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 34, 229–224. doi:10.1177/0093854806288710.

Kendrick, K., Jutengren, G., & Stattin, H. (2012). The protective role of supportive friends against bullying perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 1069–1080. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2012.02.014.

Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2012). The relationship between teacher self-efficacy and violence towards students as mediated by teacher’s attitude. Social Work Research, 36(2), 127–139. doi:10.1093/swr/svs004.

Khoury-Kassabri, M., Astor, R., & Benbenishty, R. (2009). Middle Eastern adolescents’ perpetration of school violence against peers and teachers: A cross cultural and ecological analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24, 159–182. doi:10.1177/0886260508315777.

Khoury-Kassabri, M., Benbenishty, R., Astor, R., & Zeira, A. (2004). The contribution of community, family and school variables on student victimization. American Journal of Community Psychology, 34, 187–204.

Khoury-Kassabri, M., Khoury, N., & Ali, R. (2015). Arab youth involvement in delinquency and political violence and parental control: The mediating role of religiosity. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 85, 576–585. doi:10.1007/s10464-004-7414-4.

Khoury-Kassabri, M., Mishna, F., & Massarwi, A. (2016). Cyber bullying perpetration by Arab youth: The direct and interactive role of individual, family, and neighborhood characteristics. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 1-27. 10.1177/0886260516660975.1.210

Kolip, P. (1997). Gender differences in health status during adolescence: A remarkable shift. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 9, 9–17. doi:10.1515/IJAMH.1997.9.1.9.

Laible, D. J., Carlo, G., & Roesch, S. C. (2004). Pathways to self-esteem in late adolescence: The role of parent and peer attachment, empathy, and social behaviours. Journal of Adolescence, 27, 703–716. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.05.005.

Landman-Peeters, K. M. C., Hartman, C. A., van derPompe, G., den Boer, J. A., Minderaa, R. B., & Ormel, J. (2005). Gender differences in the relation between social support, problems in parent offspring communication, and depression and anxiety. Social Science & Medicine, 60, 2549–2559. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.10.024.

Leadbeater, B. J., Kuperminc, G. P., Blatt, S. J., & Hertzog, C. (1999). A multivariate model of gender differences in adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems. Developmental psychology, 35, 1268–1282. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.5.1268.

Lewinsohn, M., Gotlib, I. H., Lewinsohn, M., Seeley, J. R., & Allen, N. B. (1998). Gender differences in anxiety disorders and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 107, 109–117. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.107.1.109.

Licitra-Kleckler, D. M., & Waas, G. A. (1993). Perceived social support among high-stress Adolescents: The role of peers and family. Journal of Adolescent Research, 8, 381–402. doi:10.1177/074355489384003.

Massarwi, A. A. (2017). The correlation between exposure to neighborhood violence and perpetration of moderate physical violence among Arab-Palestinian youth: Can it be moderated by parental support and gender? American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. doi:10.1037/ort0000262.

Massarwi, A. A., & Khoury-Kassabri, M. (2017). Serious physical violence among Arab-Palestinian adolescents: The role of exposure to neighborhood violence, perceived ethnic discrimination, normative beliefs, and, parental communication. Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 233–244. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.002.

McFarlane, A. H., Bellissimo, A., & Norman, G. R. (1995). The role of family and peers in social self-efficacy: Links to depression in adolescence. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 65, 402–404. doi:10.1037/h0079655.

Mcelhaney, K. B., Immele, A., Smith, F. D., & Allen, J. P. (2006). Attachment organization as a moderator of the link between friendship quality and adolescent delinquency. Attachment & Human Development, 8, 33–46. doi:10.1080/14616730600585250.

Meadows, S. O. (2007). Evidence of parallel pathways: Gender similarity in the impact of social support on adolescent depression and delinquency. Social Forces, 85, 1143–1167.

Mishna, F. (2012). Bullying: A relationship-based guide to assessment, prevention, and intervention. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Mishna, F., Cook, C., Gadalla, T., Daciuk, J., & Solomon, S. (2010). Cyber bullying behaviors among middle and high school students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80, 362–374. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01040.x.

Mishna, F., Khoury-Kassabri, M., Schwan, K., Wiener, J., Craig, W., Beran, T., & Daciuk, J. (2016). The contribution of social support to children and adolescents’ self-perception: The mediating role of bullying victimization. Children and Youth Services Review, 63, 120–127. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.02.013.

Mishna, F., Pepler, D., Cook, C., Craig, W., & Wiener, J. (2010). The ongoing problem of bullying in Canada: A ten-year perspective. Canadian Social Work, 12(2), 43–59.

Mishna, F., Schwan, K., Lefebrvre, R., Bhole, P., & Johnston, D. (2014). Students in distress: Unanticipated findings in a cyber bullying study. Children and Youth Services Review, 44, 341–348. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.04.010.

Mishna, F., Saini, M., & Solomon, S. (2009). Ongoing and online: Children and youth’s perceptions of cyber bullying. Children and Youth Services Review, 31, 1222–1228. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2009.05.004.

Mishna, F., & Van Wert, M. (2015). Bullying in Canada. Don Mills, ON: Oxford University Press.

Newman, B. M., Newman, P. R., Griffen, S., O’Connor, K., & Spas, J. (2007). The relationship of social support to depressive symptoms during the transition to high school. Adolescence, 42, 441–459.

Olweus, D. (2012). Cyberbullying: An overrated phenomenon? European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 9, 520–538. doi:10.1080/17405629.2012.682358.

Özbay, O., & Özcan, Y. Z. (2008). A test of Hirschi’s social bonding theory: A comparison of male and female delinquency. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 2, 134–157. doi:10.1177/0306624X07309182.

Pepler, D. J., Connolly, J., & Craig, W. M. (1993). Safe School Questionnaire. Unpublished Manuscript.

Pickering, L. E., & Vazsonyi, A. T. (2010). Does family process mediate the effect of religiosity on adolescent deviance? Revisiting the notion of spuriousness. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 37, 97–118. doi:10.1177/0093854809347813.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. doi:10.3758/BRM.40.3.879.

Raskauskas, J., & Stoltz, A. D. (2007). Involvement in traditional and electronic bullying among adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 43, 564–575. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.3.564.

Razzino, B. E., Ribordy, S. C., Grant, K., & Ferrari, J. R. (2004). Gender-related processes and drug use: Self-expression with parents, peer group selection, and achievement motivation. Adolescence, 39, 153–167.

Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., & Telch, M. J. (2010). Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse & Neglect, 34, 244–252. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009.

Reijntjes, A., Kamphuis, J. H., Prinzie, P., Boelen, P. A., Van der Schoot, M., & Telch, M. J. (2011). Prospective linkages between peer victimization and externalizing problems in children: A meta‐analysis. Aggressive Behavior, 37, 215–222. doi:10.1002/ab.20374.

Ross, C. E., & Broh, B. A. (2000). The roles of self-esteem and the sense of personal control in the academic achievement process. Sociology of Education, 73, 270–284. doi:10.2307/2673234.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2008). Gender differences in the relationship between perceived social support and student adjustment during early adolescence. School Psychology Quarterly, 23, 496–514. doi:10.1037/1045-3830.23.4.496.

Rueger, S. Y., Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2010). Relationship between multiple sources of perceived social support and psychological and academic adjustment in early adolescence: Comparisons across gender. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 47–61. doi:10.1007/s10964-008-9368-6.

Schmidt, M. E., & Bagwell, C. L. (2007). The protective role of friendships in overtly and relationally victimized boys and girls. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 53, 439–460. doi:10.1353/mpq.2007.0021.

Scholte, R. H. J., & Van Aken, M. A. G. (2006). Peer relations in adolescence. In S. Jackson & L. Goossens (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent development (pp. 175–199). New York, NY: Psychology Press.

Schraedley, M. A., Gotlib, I. H., & Hayward, C. (1999). Gender differences in correlates of depressive symptoms in adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 25, 98–108. doi:10.1016/S1054-139X(99)00038-5.

Schwartz, D., Grman, A. H., Nakamoto, J., & McKay, T. (2006). Popularity, social acceptance and aggression in adolescent peer groups: Links with academic performance and school attendance. Developmental Psychology, 42, 1116–1127. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.6.1116.

Sullivan, C. J., Wilcox, P., & Ousey, G. C. (2011). Trajectories of victimization from early to mid-adolescence. Criminal justice and behavior, 38(1), 85–104. doi:10.1177/0093854810386542.

Tanigawa, D., Furlong, M. J., Felix, E. D., & Sharkey, J. D. (2011). The protective role of perceived social support against the manifestation of depressive symptoms in peer victims. Journal of School Violence, 10, 393–412. doi:10.1080/15388220.2011.602614.

Toronto District School Board (2014) The 2014 learning opportunities index: Questions and answers. http://www.tdsb.on.ca/Portals/0/AboutUs/Research/LOI2014.pdf. Accessed 19 Aug 2015.

Ttofi, M. M., Farrington, D. P., Lösel, F., & Loeber, R. (2011). Do the victims of school bullies tend to become depressed later in life? A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research, 3, 63–73. doi:10.1108/17596591111132873.

Vazsonyi, A. T., Roberts, J. W., Huang, L., & Vaughn, M. G. (2015). Why focusing on nurture made and still makes sense: The biosocial development of self-control. In D. Delisi & M. G. Vaughn (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of biosocial criminology (pp. 263–279). New York, NY: Routledge.

Wade, T. J., Cairney, J., & Pevalin, D. J. (2002). Emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence: National panel results from three countries. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 41, 190–198. doi:10.1097/00004583-200202000-00013.

Walden, L. M., & Beran, T. N. (2010). Attachment quality and bullying behavior in school-aged youth. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 25, 5–18. doi:10.1177/0829573509357046.

Wentzel, K. R. (1998). Social relationships and motivation in middle school: The role of parents, teachers, and peers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 90, 202–209. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.90.2.202.

Wentzel, K. R., Weinberger, D. A., Ford, M. E., & Feldman, S. S. (1990). Academic achievement in preadolescence: The role of motivational, affective, and self-regulatory processes. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 11, 179–193. doi:10.1016/0193-3973(90)90004-4.

White, K. S., Bruce, S. E., Farrell, A. D., & Kliewer, W. (1998). Impact of exposure to community violence on anxiety: A longitudinal study of family social support as a protective factor for urban children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 7, 187–203. doi:10.1023/A:1022943216319.

Wight, R. G., Botticello, A. L., & Aneshensel, C. S. (2006). Socioeconomic context, social support, and adolescent mental health: A multilevel investigation. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 109–120. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-9009-2.

Wills, T. A., Resko, J. A., Ainette, M. G., & Mendoza, D. (2004). Role of parent support and peer support in adolescent substance use: a test of mediated effects. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 18, 122–134. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.18.2.122.

Windle, M. (1992). Temperament and social support in adolescence: Relations with depressive symptoms and delinquent behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 21, 1–21. doi:10.1007/BF01536980.

Wong, S. K. (2005). The effects of adolescent activities on delinquency: A differential involvement approach. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34, 321–333. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-5755-4.

Author Contributions

S.A.S.: Wrote the paper and collaborated with analyzing the data. F.M.: designed and executed the study, collaborated with writing the paper; M.K.K.: Analyzed the data and collaborated with writing the paper and edited the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (Grant number 410-2011-1001). The study was supported by The Halbert Center for Canadian Studies, the Faculty Israeli- Canadian Academic Exchange Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Attar-Schwartz, S., Mishna, F. & Khoury-Kassabri, M. The Role of Classmates’ Social Support, Peer Victimization and Gender in Externalizing and Internalizing Behaviors among Canadian Youth. J Child Fam Stud 28, 2335–2346 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0852-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0852-z