Abstract

Despite various individual studies on the quality of life (QOL) in patients with CHF, a comprehensive study has not yet been conducted; therefore, this study aims to assess the QOL of CHF patients. In the present systematic review and meta-analysis, PubMed, Scopus, and the Web of science databases were searched from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2018, using QOL and heart failure as keywords. The searches, screenings, quality assessments, and data extractions were conducted separately by two researchers. A total of 70 studies including 25,180 participants entered the final stage. The mean QOL score was 44.1 (95% confidence interval (CI) 40.6, 47.5; I2 = 99.3%) using a specific random effects method in 40 studies carried out on 12,520 patients. Moreover, according to the geographical region, heart failure patients in the Americas had higher scores. In 14 studies, in which a general SF-36 survey was implemented, the average physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS) were 33.3 (95% CI 31.9, 34.7; I2 = 88.0%) and 50.6 (95% CI 43.8, 57.4; I2 = 99.3%), respectively. The general and specific tools used in this study indicated moderate and poor QOL, respectively. Therefore, it is necessary to carry out periodic QOL measurements using appropriate tools as part of the general care of CHF patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Today, chronic heart failure (CHF) is a serious global health challenge. According to the most recent 2019 data, more than 6.2 million people in the USA are afflicted with CHF, which is projected to reach over 8 million by 2030 [1]. World Health Statistics from 2012 alone show that heart failure (HF) has created an additional burden of 180 million dollars in the health system [2]. Different physical and mental complications such as fatigue, depression, anxiety, edema, shortness of breath due to the chronic and prolonged disease course, and therapeutic processes have a serious and negative impact on the quality of life (QOL) of CHF patients resulting in lower QOLs compared with healthy individuals and other patients with chronic illnesses [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. Lower QOLs correlate with increased hospitalization times and mortality rates, and higher costs imposed on health systems, families, and patients [10,11,12].

Therefore, the regular assessment of a patients’ QOL and health promotion are key measures in increasing their survival rates [13, 14]. QOL is a multidimensional concept that is affected by economic and social factors, life satisfaction, and the severity and stage of their HF (15, 16). QOL is usually assessed using general and specific tools with previous studies primarily having been focused on the identification of QOL measuring tools (17). Despite numerous individual studies, there have been no comprehensive studies on the exact QOL status of CHF patients. This comprehensive study will help to determine the exact QOL status of HF patients at global and regional levels and on the various income levels of their countries.

QOL has been also studied on the basis of separate specific and general tools, so that we can help healthcare personnel and patients identify the elements needed to support a better QOL. The aim of the present study was to assess the QOL of CHF patients.

Methods

Eligibility criteria and search strategy

This systematic review and meta-analysis was carried out using the Cochran’s book and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement was used to report [15]. The study protocol has been registered in PROSPERO (CRD42019135720).

Inclusion criteria included all the studies that used at least one of the standard specific or general tools for measuring QOL and were published in peer-reviewed journals in English language, descriptive observational articles, and clinical trials containing basic information about participants’ QOL. The target participants with CHF aged over 15 years old, studies which have been conducted on at least 25 people and from 1 January 2000 to 31 December 2018.

Exclusion criteria included the studies that were published in non-English language and published before 2000, also review, qualitative, letter to editor studies were excluded. Studies that did not meet the minimum quality scores were also excluded. Since only studies using standardized scores were used to calculate quality of life included, studies that used raw scores to determine quality of life were excluded.

Three databases (PubMed, Scopus, and Web of science) were searched. The latest search process was carried out on 10 January 2019 to prepare the search strategy, the Boolean operators (AND, OR, and NOT), Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), truncation “*” and related text words was used. Keywords used included quality of life and heart failure.

Selection of studies and data extraction

Searching, screening, data extraction, and quality assessment were performed by two researchers (R.A.G, S.B). According to the study protocol, the studies were reviewed, and the duplicates were excluded. Studies were then reviewed by title and abstract, respectively, and the unrelated ones were excluded. Then the remaining studies entered the final stage. The extracted data items included the first author; year of publication; region based on WHO category, socioeconomic status based on world bank category, country; sampling method; age; design; stage of HF; and instrument characteristics, gender, risk of bias, and quality of life score.

Quality assessment and data synthesis

To evaluate the methodological quality of the studies, two different tools were used based on the type of study. To evaluate the quality of descriptive studies, Hoy et al.’s 10-item tool was used and assessed the studies for external and internal validity [16]. Moreover, Jadad’s tool was used to assess the risk of bias in two clinical trials [17]. All the eligible studies were included in the synthesis after a systematic review. Data were combined with the forest plot. The quality of life in heart failure patients was evaluated by random-effects model. The heterogeneity of the preliminary studies was evaluated with I2 tests. Sub-group analysis was conducted to determine heterogeneity based on the type of tools, gender, and publication year. Meta-analysis was performed using STATA 14 (StataCorp, Texas, USA) statistical software.

Results

Study selection

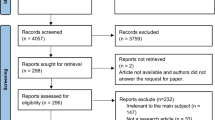

A total of 5022 articles were found while searching four databases. After excluding duplicate articles, 2349 articles entered the next phase where articles were reviewed in terms of title and abstract, of which 2149 articles were excluded due to lack of meeting the inclusion criteria. At the last phase, 200 full-text articles were reviewed, of which 70 articles had the inclusion criteria. Out of 130 articles were also excluded for reasons included review (n = 13), qualitative (n = 3), no quality (n = 3), no full text (n = 18), non-English n = (34), letter to editor (n = 18), and used raw score to determine the QOL (1) [18] (Fig. 1).

Study characteristics

A total of 70 studies carried out 25,180 patients with HF in 23 countries from 2001 to 2018 entered the final phase. Most studies were conducted in Americans (n = 27) and European (n = 25). Most studies were conducted in countries with high SDI (n = 67). Most studies (n = 40) used consecutive sampling. The most commonly used general and specific tools used included SF-36 (n = 15) and MLHFQ (n = 41). The type of studies included descriptive (n = 65), cohort (n = 2), and RCT studies (n = 3). Also, most of studies were multicenter studies (n = 53). Of the 50,916 people, 28,371 were nurses. All of the studies entered had low bias risk and good quality (Table 1)

Main results

Instruments

Various general and specific tools were used in 70 studies entered. Similar type of general or specific tool was used to measure quality of life in 53 studies, and more than one type of tool was used in other studies. The general tools included SF-36 (n = 14), ED-5Q (n = 6), WHOQOL-BREF (n = 3), and SF-12(n = 3). Specific tools included MLHFQ (n = 41), KCCQ (n = 9), MQOL (n = 2), and other tools included DHP, CDC HRQOL, CCHFQ, HFSS, LVD-36, MacNew , MILQ, NHP, QLI, and quality of life index. The full details of used instruments including full name, abbreviation, type of questioner (general/specific), dimensions and items, scores mentioned in Supplementary Table 1.

Quality of life

Quality of life based on specific tools: MLHFQ

Using 41 studies and 12,578 participants, the QOL was assessed by The Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLHFQ). In these studies, the mean of the total QOL score reported in 40 studies (12,520 patients) was between 13.0 and 66.9. Based on the results of the random effects model, the pooled mean of the total QOL was 44.1 (95% CI 40.6, 47.5; I2 = 99.3%). Subgroup analyses based-on continents, showed the pooled mean of the total QOL score in Americans (48.0) was higher than Europe (45.5) and Asia (35.1), and the difference with Asia was statistically significant (p value = 0.014) (Fig. 2). Therefore, based on total MLHFQ scores, the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in Asian HF patients was better than in American patients, indicating less of a disease impact in Asians.

Target population in five studies and mean age of 15 studies was higher than 60 years. Nineteen studies with 4080 participants and 20 studies with 8046 participants were categorized as adult and elderly age groups, respectively. Subgroup analysis based on age groups revealed that the pooled mean total QOL score in the adult group [41.2 (95% CI 33.5, 48.9; I2 = 99.4%)] was lower than in the elderly group [46.6 (95% CI 43.0, 50.2; I2 = 99.1%)] (p value = 0.154) indicating that heart failure in elderly patients probably has a larger effect on their QOLs.

The physical and emotional subscales of quality of life scale were assessed and reported in 24 out of 40 studies. Based on the results of the random effects method, the pooled mean of the physical and emotional subscales was 20.1 (95% CI 17.4, 22.9; I2 = 99.3%) and 8.8 (95% CI 7.5, 10.1; I2 = 98.6%), respectively. Subgroup analysis based on continents showed that the pooled mean of the physical and emotional subscales in America were higher than in Europe or Asia. For the physical subscale, the difference between America and Asia was significant (21.4 vs. 12.5; p value < 0.001) (Supplementary Table 2).

The pooled mean of the physical subscale in elderly patients was 1.5 times greater than that of the adult age group (22.9 (95% CI 20.0, 25.9; I2 = 99.0%) vs. 15.4 (95% CI 10.5, 20.3; I2 = 99.2%); p value = 0.014). The pooled mean of the emotional subscale in elderly patients was 1.4 times greater than that of the adult age group (9.8 (95% CI 8.5, 11.0; I2 = 97.5%) vs. 7.0 (95% CI 5.1, 9.0; I2 = 97.9%); p value = 0.028).

The total MLHFQ score by gender was reported in 15 out of 40 studies. For 2174 male and 1,724 female patients, the pooled mean total MLHFQ score was 40.7 (95% CI 36.6, 44.9; I2 = 96.7%) and 45.6 (95% CI 42.1, 49.1; I2 = 93.3%), respectively (p value = 0.087). The QOL for female patients was lower than that in male patients, and this difference was also apparent in continental subgroups (Fig. 2). Out of 15 studies, 7 included physical and emotional subscales. The pooled means of the physical subscales in male and female patients were 19.2 (95% CI 16.2, 22.2; I2 = 97.0%) and 20.4 (95% CI 17.7, 23.1; I2 = 95.6%), respectively (p value = 0.562), and 8.5 (95% CI 7.4, 9.6; I2 = 91.9%) and 9.3 (95% CI 7.7, 10.9; I2 = 94.5%), respectively for the emotional subscales (p value = 0.413) (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Quality of life based on general tools: SF-36

Twenty-one studies used the short form (SF) health survey to assess the QOL. Fourteen out of 21 studies used the SF-36 with all eight scaled scores, but one study reported using only the physical functioning (PF) scale. Three studies used the shorter SF-12 version and reported the physical component summary (PCS) and the mental component summary (MCS). Four studies using the SF-36 assessed and reported two summary scales (PCS, MCS). Each of the eight health concepts was measured on a scale from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better health.

Based on the results of the random effects method, the pooled means of the PCS and the MCS scales for 2034 patients (1061 male and 973 female) were 33.3 (95% CI 31.9, 34.7; I2 = 88.0%) and 50.6 (95% CI 43.8, 57.4; I2 = 99.3%), respectively.

The mean score of general health perception was between 26.8 and 67.0, and the global pooled mean was 44.9 (95% CI 40.8, 49.0; I2 = 97.4%). Subgroup analysis showed that the pooled mean of general health perception in America was 1.4 times higher than that in Asia (p value = 0.036) (Fig. 3).

Using a seven scale SF-36 (vitality, body pain, mental health, physical functioning, physical role, emotional role, and social functioning), the global pooled mean for physical role functioning (40.5) produced the lowest QOL scores and social role functioning produced the highest (64.8). In America, the pooled mean of physical functioning (47.2) had the lowest QOL score, and the emotional role functioning (79.1) had the highest QOL score. The pooled mean of mental health (52.6) had the highest QOL score in Asia. The mean scores for general health perceptions and for the other seven scales were higher in America than in Europe or Asia. The differences of the pooled means between America and Asia were significant in bodily pain, mental health, and social role functioning (p value < 0.05) (Table 2).

Quality of life based on other tools

The QOL in HF patients was assessed in 8 global studies using the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ). In seven of these, the overall summary score was calculated and reported by summing the scores of the physical limitations, symptoms, QOL, and social-functioning domains. The mean overall summary score for 4272 participants was 55.0 to 70.5 and the pooled mean was 60.9 (95% CI 56.2, 65.5; I2 = 96.9%). The KCCQ subscale was assessed in only three studies.

The QOL in 6 global studies was assessed using the ED-5Q questionnaire. In the health state description component, 4 studies reported an overall score and the pooled mean was 0.608 (95% CI 0.569, 0.647; I2 = 97.6%) with the lower pooled mean score being self-care and the higher pooled mean score being daily activities. In the evaluation component of the ED-5Q, five studies used a visual analog scale (VAS) and the pooled mean of the VAS was 54.6 (95% CI 48.4, 60.8; I2 = 99.3%). Sixteen studies investigated the QOL of HF patients with 13 other tools (Supplementary Table 3).

Meta-regression

The results of univariate meta-regression analyses based-on MLHFQ, showed gender of participants (male-to-female ratio) variable not significantly contributed to heterogeneity of total mean score and sub-scale of QoL in the world (P > 0.05); but, publication year of study and continent showed a significant heterogeneity (Coef. = − 0.93, P = 0.023, and Coef. = − 6.1, P = 0.006), that explained 10.9% and 16.8% of between-study variation. Based-on sub-scale of MLHFQ, significant association only shown in physical sub-scale and continent (Coef. = − 4.1, P = 0.020) (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Discussion

Quality of life

The goal of all physical and mental treatments is to improve the QOL for CHF patients. This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the QOL of CHF patients from 2000 to 2018. A total of 70 studies performed on 25,180 patients entered the final stage. The most commonly used special tool was the MHLFQ. The MHLFQ tool was used as a specific tool to assess patients’ QOLs in 40 studies. Meta-analysis results indicated that the mean QOL in HF patients was 44.1. Based on the cutoff point in the MHLFQ tool, a higher score indicated a lower QOL, so that scores less than 24, 24–45, and above 45 indicated a good, moderate, and poor QOL, respectively [87]. Therefore, the results of the present study indicate a moderate to poor QOL in HF patients. According to the literature searches carried out by researchers, there have been no systematic reviews that investigated the QOL of HF patients based on the MHLFQ tool.

The results also showed that HF patients had a poorer QOL in the USA compared with other parts of world, yet the exact cause of this difference is not known. However, this result could have been due to the differences in the sample sizes of the studies from different parts of the world selected for this review, most of which were from the Americas. It is also possible that these results are due to an inequality of access to HF care services and the differences in the severity of symptoms in various racial groups [88].

The results also showed that the physical and mental scores in the elderly age group were 1.5 and 1.4 times higher than that of the adult age group, although these differences were not statistically significant. The results also showed that the QOL in the elderly age group was more disrupted than in adults with HF, which was consistent with previous studies in terms of disrupted dimensions, but it is inconsistent with previous studies regarding overall QOL scores [89,90,91].

The difference may be due to the type and sample size of the comparative studies since the present study is a review with sample sizes higher than in previous individual studies. The average QOL score was 40.7 in men and 45.6 in women, which indicated that the female QOL was more disrupted, which is consistent with the previous individual study [92]. This difference can be attributed to the effect of the different sample sizes of women and men surveyed in the present study. It can also be due to the difference in the time taken for patients to adapt to the disease since men adapted in a shorter time period. This difference can also be due to the different life status and roles played by the two genders since men are more likely to be physically and socially supported than are women. The most commonly used general tool was the SF-36 health survey, which showed that the mean score of the physical component dimension was 33.3 (31.9–34.7), and the mental component dimension was 50.6 (43.8–57.4).

The mean general health dimension was 44.9, which was consistent with previous individual studies on cardiac patients other than those with HF (46.56) [93] and less than in patients with acute coronary artery disease (55.63) [94]. It was also consistent with previous individual studies on other heart diseases in terms of the physical dimension (31.67) [93] and less than in acute coronary artery disease (58.37) [94]. The results also showed that HF patients have a lower QOL in the physical dimension as compared with other chronic patients, such as thalassemic patients (56.78 (52.74–74.5) [95] and in the mental dimension in thalassemic patients (51.64 (59.6–71.1) [95]. Regular QOL measurements can help identify patients with poor QOLs, and help healthcare providers more accurately identify specific dimensions that require more attention. In addition, it can be used as a tool to assess the effect of different treatment interventions on the disease process. It is essential to take into account factors affecting the QOL in HF patients to manage them more effectively and to use effective interventions to improve their QOLs.

According to the International Guideline and ACCF/AHA guideline, considering the multidimensional concept of quality of life, it is necessary to pay attention to the physical and psychological dimensions of patients; the following recommendations can improve the quality of life of patients with heart failure: disease confidence indicates a person’s sense of illness that is higher than the individual’s dimensions of illness. This feeling improves through self-care. Understanding CHF, due to the different order of occurrence of the symptoms of the disease in different patients of CHF, which makes the disease unique to each individual, it helps the patient to obtain adequate information about the disease. The first step in managing the disease and enhancing the quality of life is to get enough information about the disease. Symptom monitoring, a daily checkup of the most common symptoms of the disease, such as shortness of breath, weight loss, blood pressure changes and coughing, will prevent the patient from becoming acutely ill. Family support, due to the long-term and chronic illness of the patient, family support can lead to improved quality of life for patients [96,97,98].

Limitations

Although studies included were carried out on patients with varying degrees of disease severity, the QOl score was not expressed in terms of severity and history of disease in most studies; however, it has been shown that the disease severity can have a significant impact on QOl. Attempts were also made to contact with authors of studies lacking relevant information. Most of the studies were descriptive studies, which have their specific limitations.

Strengths

To the best of researchers’ knowledge, this is the first study that reviews QOl of HF patients at the global level. In this study, QOl was also assessed based on the geographical area determined by World Health Organization (WHO) and the income level identified by Bank World, which could help health policy-makers and healthcare staffs in the region to help improve QOl more accurately. The present study also assessed the QOl separately using specific and general tools. Another strength of this study was the use of a variety of tools to measure the quality of life in patients with HF.

Conclusion

The present systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted to evaluate the QOL of HF patients. The results showed a moderate to poor QOL in the physical dimension and a moderate to high QOL in the mental dimension using specific and general tools, respectively. The results of the present study, using specific and general tools, indicated the importance of QOL assessment at appropriate time periods, determining the exact treatment dimensions required, and implementing comprehensive QOL promotion programs in all physical and mental dimensions.

References

Benjamin EJ, Muntner P, Bittencourt MS (2019) Heart disease and stroke statistics-2019 update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 139(10):e56–e528

Cook C, Cole G, Asaria P, Jabbour R, Francis DP (2014) The annual global economic burden of heart failure. Int J Cardiol 171(3):368–376

Dokainish H, Teo K, Zhu J, Roy A, AlHabib KF, ElSayed A, Palileo-Villaneuva L, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Karaye K, Yusoff K (2017) Global mortality variations in patients with heart failure: results from the International Congestive Heart Failure (INTER-CHF) prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health 5(7):e665–e672

Juenger J, Schellberg D, Kraemer S, Haunstetter A, Zugck C, Herzog W, Haass M (2002) Health related quality of life in patients with congestive heart failure: comparison with other chronic diseases and relation to functional variables. Heart 87(3):235–241

Park J, Moser DK, Griffith K, Harring JR, Johantgen M (2019) Exploring symptom clusters in people with heart failure. Clin Nurs Res 28(2):165–181

Salyer J, Flattery M, Lyon DE (2019) Heart failure symptom clusters and quality of life. Heart Lung 48(5):366-372

Sokoreli I, De Vries J, Pauws S, Steyerberg E (2016) Depression and anxiety as predictors of mortality among heart failure patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev 21(1):49–63

Van Jaarsveld CH, Sanderman R, Miedema I, Ranchor AV, Kempen GI (2001) Changes in health-related quality of life in older patients with acute myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure: a prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc 49(8):1052–1058

Zambroski CH, Moser DK, Bhat G, Ziegler C (2005) Impact of symptom prevalence and symptom burden on quality of life in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 4(3):198–206

Alla F, Briançon S, Guillemin F, Juillière Y, Mertès PM, Villemot JP, Zannad F, Investigators E (2002) Self-rating of quality of life provides additional prognostic information in heart failure. Insights into the EPICAL study. Eur J Heart Fail 4(3):337–343

Angermann CE, Gelbrich G, Störk S, Gunold H, Edelmann F, Wachter R, Schunkert H, Graf T, Kindermann I, Haass M (2016) Effect of escitalopram on all-cause mortality and hospitalization in patients with heart failure and depression: the MOOD-HF randomized clinical trial. Jama 315(24):2683–2693

Gupta A, Allen LA, Bhatt DL, Cox M, DeVore AD, Heidenreich PA, Hernandez AF, Peterson ED, Matsouaka RA, Yancy CW (2018) Association of the hospital readmissions reduction program implementation with readmission and mortality outcomes in heart failure. JAMA Cardiol 3(1):44–53

Binanay C, Califf RM, Hasselblad V, O'connor C, Shah M, Sopko G, Stevenson L, Francis G, Leier C, Miller L (2005) Evaluation study of congestive heart failure and pulmonary artery catheterization effectiveness: the ESCAPE trial. Jama 294(13):1625–1633

Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Guallar-Castillon P, Pascual CR, Otero CM, Montes AO, Garcia AN, Conthe P, Chiva MO, Banegas JR, Herrera MC (2005) Health-related quality of life as a predictor of hospital readmission and death among patients with heart failure. Arch Intern Med 165(11):1274–1279. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.165.11.1274

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med 151(4):264–269

Hoy D, Brooks P, Woolf A, Blyth F, March L, Bain C, Baker P, Smith E, Buchbinder R (2012) Assessing risk of bias in prevalence studies: modification of an existing tool and evidence of interrater agreement. J Clin Epidemiol 65(9):934–939

Clark HD, Wells GA, Huët C, McAlister FA, Salmi LR, Fergusson D, Laupacis A (1999) Assessing the quality of randomized trials: reliability of the Jadad scale. Control Clin Trials 20(5):448–452

Piotrowicz E, Stepnowska M, Leszczyńska-Iwanicka K, Piotrowska D, Kowalska M, Tylka J, Piotrowski W, Piotrowicz R (2015) Quality of life in heart failure patients undergoing home-based telerehabilitation versus outpatient rehabilitation–a randomized controlled study. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 14(3):256–263

AbuRuz ME, Alaloul F, Saifan A, Masa'deh R, Abusalem S (2015) Quality of life for Saudi patients with heart failure: a cross-sectional correlational study. Global J Health Sci 8(3):49–58. https://doi.org/10.5539/gjhs.v8n3p49

Alaloul F, AbuRuz ME, Moser DK, Hall LA, Al-Sadi A (2017) Factors associated with quality of life in Arab patients with heart failure. Scand J Caring Sci 31(1):104–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12324

Alla F, Briancon S, Guillemin F, Juilliere Y, Mertes PM, Villemot JP, Zannad F (2002) Self-rating of quality of life provides additional prognostic information in heart failure. Insights into the EPICAL study. Eur J Heart Fail 4(3):337–343

Arestedt K, Saveman BI, Johansson P, Blomqvist K (2013) Social support and its association with health-related quality of life among older patients with chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 12(1):69–77. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474515111432997

Audi G, Korologou A, Koutelekos I, Vasilopoulos G, Karakostas K, Makrygianaki K, Polikandrioti M (2017) Factors affecting health related quality of life in hospitalized patients with heart failure. Cardiol Res Pract 2017:4690458. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/4690458

Auld JP, Mudd JO, Gelow JM, Hiatt SO, Lee CS (2018) Self-care moderates the relationship between symptoms and health-related quality of life in heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 33(3):217–224. https://doi.org/10.1097/jcn.0000000000000447

Azevedo A, Bettencourt P, Alvelos M, Martins E, Abreu-Lima C, Hense HW, Barros H (2008) Health-related quality of life and stages of heart failure. Int J Cardiol 129(2):238–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2007.07.091

Bean MK, Gibson D, Flattery M, Duncan A, Hess M (2009) Psychosocial factors, quality of life, and psychological distress: ethnic differences in patients with heart failure. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs 24(4):131–140. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7117.2009.00051.x

Bennett SJ, Perkins SM, Lane KA, Deer M, Brater DC, Murray MD (2001) Social support and health-related quality of life in chronic heart failure patients. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehab 10(8):671–682

Berg J, Lindgren P, Kahan T, Schill O, Persson H, Edner M, Mejhert M (2014) Health-related quality of life and long-term morbidity and mortality in patients hospitalised with systolic heart failure. JRSM Cardiovasc Dis 3:2048004014548735. https://doi.org/10.1177/2048004014548735

Blinderman CD, Homel P, Billings JA, Portenoy RK, Tennstedt SL (2008) Symptom distress and quality of life in patients with advanced congestive heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manag 35(6):594–603. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.06.007

Borumandpour M, Valizadeh G, Dehghan A, Pourmarjani A, Ahmadifar M (2016) Application of WHOQOL-BREF for the evaluation of the quality of life in elderly patients with heart failure. Biosci Biotechnol Res Commun 9(4):878–883

Britz JA, Dunn KS (2010) Self-care and quality of life among patients with heart failure. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 22(9):480–487. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2010.00538.x

Brostrom A, Stromberg A, Dahlstrom U, Fridlund B (2004) Sleep difficulties, daytime sleepiness, and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 19(4):234–242

Buck HG, Lee CS, Moser DK, Albert NM, Lennie T, Bentley B, Worrall-Carter L, Riegel B (2012) Relationship between self-care and health-related quality of life in older adults with moderate to advanced heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 27(1):8–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182106299

Cal A, Altay B (2017) The quality of life and home care needs of patients treated for heart failure. Pakistan Heart J 50(1):6–13

Carels RA (2004) The association between disease severity, functional status, depression and daily quality of life in congestive heart failure patients. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehab 13(1):63–72. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:qure.0000015301.58054.51

Carson P, Tam SW, Ghali JK, Archambault WT, Taylor A, Cohn JN, Braman VM, Worcel M, Anand IS (2009) Relationship of quality of life scores with baseline characteristics and outcomes in the African-American heart failure trial. J Card Fail 15(10):835–842. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2009.05.016

Chan HY, Yu DS, Leung DY, Chan AW, Hui E (2016) Quality of life and palliative care needs of elderly patients with advanced heart failure. J Geriatr Cardiol 13(5):420–424. https://doi.org/10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.05.016

Chen HM, Clark AP, Tsai LM, Lin CC (2010) Self-reported health-related quality of life and sleep disturbances in Taiwanese people with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 25(6):503–513. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181e15c37

Chu SH, Lee WH, Yoo JS, Kim SS, Ko IS, Oh EG, Lee J, Choi M, Cheon JY, Shim CY, Kang SM (2014) Factors affecting quality of life in Korean patients with chronic heart failure. Jpn J Nurs Sci 11(1):54–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12002

Comin-Colet J, Anguita M, Formiga F, Almenar L, Crespo-Leiro MG, Manzano L, Muniz J, Chaves J, de Frutos T, Enjuanes C (2016) Health-related quality of life of patients with chronic systolic heart failure in Spain: results of the VIDA-IC study. Rev Esp Cardiol (English ed) 69(3):256–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rec.2015.07.030

De Leon CFM, Grady KL, Eaton C, Rucker-Whitaker C, Janssen I, Calvin J, Powell LH (2009) Quality of life in a diverse population of patients with heart failure baseline findings from the heart failure adherence and retention trial (HART). J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 29(3):171–178

De Rivas B, Permanyer-Miralda G, Brotons C, Aznar J, Sobreviela E (2008) Health-related quality of life in unselected outpatients with heart failure across Spain in two different health care levels. Magnitude and determinants of impairment: the INCA study. Qual Life Res 17(10):1229–1238. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-008-9397-3

Demir M, Unsar S (2011) Assessment of quality of life and activities of daily living in Turkish patients with heart failure. Int J Nurs Pract 17(6):607–614. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-172X.2011.01980.x

DeWolfe A, Gogichaishvili I, Nozadze N, Tamariz L, Quevedo HC, Julian E, Hebert K (2012) Depression and quality of life among heart failure patients in Georgia, Eastern Europe. Congest Heart Fail (Greenwich, Conn) 18(2):107–111. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7133.2011.00226.x

Edwards MK, Loprinzi PD (2016) Sedentary behavior & health-related quality of life among congestive heart failure patients. Int J Cardiol 220:520–523. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2016.06.256

Ekman I, Fagerberg B, Lundman B (2002) Health-related quality of life and sense of coherence among elderly patients with severe chronic heart failure in comparison with healthy controls. Heart Lung 31(2):94–101

Enjuanes C, Klip IT, Bruguera J, Cladellas M, Ponikowski P, Banasiak W, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Meer P, Jankowska EA, Comin-Colet J (2014) Iron deficiency and health-related quality of life in chronic heart failure: results from a multicenter European study. Int J Cardiol 174(2):268–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.03.169

Erceg P, Despotovic N, Milosevic DP, Soldatovic I, Zdravkovic S, Tomic S, Markovic I, Mihajlovic G, Brajovic MD, Bojovic O, Potic B, Davidovic M (2013) Health-related quality of life in elderly patients hospitalized with chronic heart failure. Clin Interv Aging 8:1539–1546. https://doi.org/10.2147/cia.s53305

Fotos NV, Giakoumidakis K, Kollia Z, Galanis P, Copanitsanou P, Pananoudaki E, Brokalaki H (2013) Health-related quality of life of patients with severe heart failure. A cross-sectional multicentre study. Scand J Caring Sci 27(3):686–694. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01078.x

Franzén K, Saveman BI, Blomqvist K (2007) Predictors for health related quality of life in persons 65 years or older with chronic heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 6(2):112–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2006.06.001

Gallagher AM, Lucas R, Cowie MR (2018) Assessing health-related quality of life in heart failure patients attending an outpatient clinic: a pragmatic approach. ESC Heart Fail. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.12363

Gott M, Barnes S, Parker C, Payne S, Seamark D, Gariballa S, Small N (2006) Predictors of the quality of life of older people with heart failure recruited from primary care. Age Ageing 35(2):172–177. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afj040

Hägglund L, Boman K, Olofsson M, Brulin C (2007) Fatigue and health-related quality of life in elderly patients with and without heart failure in primary healthcare. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 6(3):208–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2006.09.004

Hallas CN, Wray J, Andreou P, Banner NR (2011) Depression and perceptions about heart failure predict quality of life in patients with advanced heart failure. Heart Lung 40(2):111–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2009.12.008

Hatmi ZN, Shaterian M, Kazemi MA (2007) Quality of life in patients hospitalized with heart failure: A novel two questionnaire study. Acta Med Iran 45(6):493–500

Heo S, Moser DK, Lennie TA, Zambroski CH, Chung ML (2007) A comparison of health-related quality of life between older adults with heart failure and healthy older adults. Heart Lung J Acute Crit Care 36(1):16–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2006.06.003

Heo S, Moser DK, Chung ML, Lennie TA (2012) Social status, health-related quality of life, and event-free survival in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 11(2):141–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2010.10.003

Hou N, Chui MA, Eckert GJ, Oldridge NB, Murray MD, Bennett SJ (2004) Relationship of age and sex to health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. Am J Crit Care 13(2):153–161

Huang TY, Moser DK, Hwang SL, Lennie TA, Chung M, Heo S (2010) Comparison of health-related quality of life between American and Taiwanese heart failure patients. J Transcult Nurs 21(3):212–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659609358779

Hwang SL, Liao WC, Huang TY (2014) Predictors of quality of life in patients with heart failure. Jpn J Nurs Sci 11(4):290–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/jjns.12034

Iqbal J, Francis L, Reid J, Murray S, Denvir M (2010) Quality of life in patients with chronic heart failure and their carers: a 3-year follow-up study assessing hospitalization and mortality. Eur J Heart Fail 12(9):1002–1008. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfq114

Jaarsma T, Lesman-Leegte GAT, Cleuren GVJ, Lucas CMHB (2005) Measuring quality of life in heart failure: One versus multiple items. Neth Hear J 13(10):338–342

Jorge AJL, Rosa MLG, Correia D, Martins WA, Ceron DMM, Coelho LCF, Soussume WSN, Kang HC, Moscavitch SD, Mesquita ET (2017) Evaluation of quality of life in patients with and without heart failure in primary care. Arq Bras Cardiol 109(3):248–252. https://doi.org/10.5935/abc.20170123

Kato N, Kinugawa K, Seki S, Shiga T, Hatano M, Yao A, Hirata Y, Kazuma K, Nagai R (2011) Quality of life as an independent predictor for cardiac events and death in patients with heart failure. Circulation 75(7):1661–1669

Kaul P, Reed SD, Hernandez AF, Howlett JG, Ezekowitz JA, Li Y, Zheng Y, Rouleau JL, Starling RC, O'Connor CM, Califf RM, Armstrong PW (2013) Differences in treatment, outcomes, and quality of life among patients with heart failure in Canada and the United States. JACC Heart Fail 1(6):523–530. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2013.07.004

Lee KS, Lennie TA, Wu JR, Biddle MJ, Moser DK (2014) Depressive symptoms, health-related quality of life, and cardiac event-free survival in patients with heart failure: a mediation analysis. Qual Life Res Int J Qual Life Asp Treat Care Rehab 23(6):1869–1876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-014-0636-5

Lesman-Leegte I, Jaarsma T, Coyne JC, Hillege HL, Van Veldhuisen DJ, Sanderman R (2009) Quality of life and depressive symptoms in the elderly: a comparison between patients with heart failure and age- and gender-matched community controls. J Card Fail 15(1):17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cardfail.2008.09.006

Liu MH, Wang CH, Lee CM, Huang YY, Cherng WJ (2011) Disease knowledge, self-care behaviours and life quality in heart failure: experience of the Taiwan national health care. Brunei Int Med J 7(5):269–279

Loo DW, Jiang Y, Koh KW, Lim FP, Wang W (2016) Self-efficacy and depression predicting the health-related quality of life of outpatients with chronic heart failure in Singapore. Appl Nurs Res 32:148–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2016.07.007

Luo N, O'Connor CM, Cooper LB, Sun JL, Coles A, Reed SD, Whellan DJ, Piña IL, Kraus WE, Mentz RJ (2018) Relationship between changing patient-reported outcomes and subsequent clinical events in patients with chronic heart failure: insights from HF-ACTION. Eur J Heart Fail. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejhf.1299

Lupon J, Gastelurrutia P, de Antonio M, Gonzalez B, Cano L, Cabanes R, Urrutia A, Diez C, Coll R, Altimir S, Bayes-Genis A (2013) Quality of life monitoring in ambulatory heart failure patients: temporal changes and prognostic value. Eur J Heart Fail 15(1):103–109. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurjhf/hfs133

Macabasco-O'Connell A, DeWalt DA, Broucksou KA, Hawk V, Baker DW, Schillinger D, Ruo B, Bibbins-Domingo K, Holmes GM, Erman B, Weinberger M, Pignone M (2011) Relationship between literacy, knowledge, self-care behaviors, and heart failure-related quality of life among patients with heart failure. J Gen Intern Med 26(9):979–986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-011-1668-y

Masoudi FA, Rumsfeld JS, Havranek EP, House JA, Peterson ED, Krumholz HM, Spertus JA (2004) Age, functional capacity, and health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail 10(5):368–373

Pantilat SZ, O'Riordan DL, Rathfon MA, Dracup KA, De Marco T (2016) Etiology of pain and its association with quality of life among patients with heart failure. J Palliat Med 19(12):1254–1259. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2016.0095

Patidar AB, Andrews GR, Seth S (2011) Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea, associated risk factors, and quality of life among Indian congestive heart failure patients: a cross-sectional survey. J Cardiovasc Nurs 26(6):452–459. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0b013e31820a048e

Pelegrino VM, Dantas RAS, Clark AM (2011) Health-related quality of life determinants in outpatients with heart failure. Rev Lat Am Enferm 19(3):451–457. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-11692011000300002

Pressler SJ, Subramanian U, Kareken D, Perkins SM, Gradus-Pizlo I, Sauve MJ, Ding Y, Kim J, Sloan R, Jaynes H, Shaw RM (2010) Cognitive deficits and health-related quality of life in chronic heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 25(3):189–198. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181ca36fe

Ramos S, Prata J, Rocha-Goncalves F, Bettencourt P, Coelho R (2017) Quality of life predicts survival and hospitalisation in a heart failure Portuguese population. Appl Res Qual Life 12(1):35–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-016-9449-8

Riegel B, Moser DK, Carlson B, Deaton C, Armola R, Sethares K, Shively M, Evangelista L, Albert N (2003) Gender differences in quality of life are minimal in patients with heart failure. J Card Fail 9(1):42–48. https://doi.org/10.1054/jcaf.2003.1

Saccomann I, Cintra FA, Gallani M (2010) Health-related quality of life among the elderly with heart failure: a generic measurement. Sao Paulo Med J 128(4):192–196

Silavanich V, Nathisuwan S, Phrommintikul A, Permsuwan U (2018) Relationship of medication adherence and quality of life among heart failure patients. Heart Lung. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2018.09.009

Son YJ, Song Y, Nam S, Shin WY, Lee SJ, Jin DK (2012) Factors associated with health-related quality of life in elderly Korean patients with heart failure. J Cardiovasc Nurs 27(6):528–538. https://doi.org/10.1097/JCN.0b013e31823fa38a

Sousa MM, Oliveira JDS, Soares M, Bezerra S, Araujo AA, Oliveira S (2017) Association of social and clinical conditions to the quality of life of patients with heart failure. Rev Gaucha Enferm 38(2):e65885. https://doi.org/10.1590/1983-1447.2017.02.65885

Yu DS, Lee DT, Woo J (2004) Health-related quality of life in elderly Chinese patients with heart failure. Res Nurs Health 27(5):332–344. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20030

Yu DS, Chan HY, Leung DY, Hui E, Sit JW (2016) Symptom clusters and quality of life among patients with advanced heart failure. Journal of geriatric cardiology 13(5):408–414. https://doi.org/10.11909/j.issn.1671-5411.2016.05.014

Zachariah D, Stevens D, Sidorowicz G, Spooner C, Rowell N, Taylor J, Kay R, Salek MS, Kalra PR (2017, 249) Quality of life improvement in older patients with heart failure initiated on ivabradine: Results from the UK multi-centre LIVE:LIFE prospective cohort study. Int J Cardiol:313–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.08.001

Behlouli H, Feldman DE, Ducharme A, Frenette M, Giannetti N, Grondin F, Michel C, Sheppard R, Pilote L (2009) Identifying relative cut-off scores with neural networks for interpretation of the Minnesota Living with Heart Failure questionnaire. In: 2009 Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society. IEEE, pp 6242-6246

Blair JE, Huffman M, Shah SJ (2013) Heart failure in north america. Curr Cardiol Rev 9(2):128–146

Jenkinson C, Jenkinson D, Shepperd S, Richard L, Petersen S (1997) Evaluation of treatment for congestive heart failure in patients aged 60 years and older using generic measures of health status (SF-36 and COOP charts). Age Ageing 26(1):7–13

Johansson P, Dahlström U, Broström A (2006) Factors and interventions influencing health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure: a review of the literature. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 5(1):5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejcnurse.2005.04.011

Varvaro F, Olds N, Zullo T, Murali S (1999) Determining quality of life in older and younger women with congestive heart failure and myocardial infarction. Am J Geriatr Cardiol 8(1):15–20

Strömberg A, Mårtensson J (2003) Gender differences in patients with heart failure. Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2(1):7–18

Karakurt P, Aşılar RH, Yildirim A, Memiş Ş (2018) Determination of hopelessness and quality of life in patients with heart disease: an example from Eastern Turkey. J Relig Health 57(6):2092–2107

Silva SAD, Passos SRL, Carballo MT, Figueiró M (2011) Quality of life assessment after acute coronary syndrome: systematic review. Arq Bras Cardiol 97(6):526–540

Arian M, Mirmohammadkhani M, Ghorbani R, Soleimani M (2019) Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in beta-thalassemia major (β-TM) patients assessed by 36-item short form health survey (SF-36): a meta-analysis. Qual Life Res 28(2):321–334

Sears SF, Woodrow L, Cutitta K, Ford J, Shea JB, Cahill J (2013) A patient’s guide to living confidently with chronic heart failure. Circulation 127(13):e525–e528

Heo S, Lennie TA, Okoli C, Moser DK (2009) Quality of life in patients with heart failure: ask the patients. Heart Lung 38(2):100–108

Yancy CW, Jessup M, Bozkurt B, Butler J, Casey DE, Drazner MH, Fonarow GC, Geraci SA, Horwich T, Januzzi JL (2013) 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol 62(16):e147–e239

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Moradi, M., Daneshi, F., Behzadmehr, R. et al. Quality of life of chronic heart failure patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart Fail Rev 25, 993–1006 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-019-09890-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10741-019-09890-2