Abstract

Background

Adjuvant endocrine therapy is a gold standard in early-stage, hormone receptor positive breast cancer. In postmenopausal women, aromatase inhibitors (AIs) are associated with improved outcome compared to tamoxifen monotherapy. Differences in the toxicity profiles of these drugs are described; however, little is known about whether the risk of adverse events changes over time.

Methods

Sequential reports of large, randomized, adjuvant endocrine therapy trials comparing AIs to tamoxifen were reviewed. Data on pre-specified adverse events were extracted including cardiovascular events, bone fractures, cerebrovascular disease, endometrial cancer, secondary malignancies excluding breast cancer, venous thrombosis and death without recurrence. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for each adverse event at each time over the course of follow-up. The change in the ORs for adverse events over time was evaluated using weighted linear regression.

Results

Analysis included 21 reports of 7 trials comprising 30,039 patients and reporting outcomes between 28 and 128 months of follow-up. Compared to tamoxifen, AIs use was associated with a significant reduction in the magnitude of increased odds of bone fracture over time (β = − 0.63, p = 0.013). There was a non-significant decrease in the magnitude of reduced odds of secondary malignancies over time (β = 0.448, p = 0.094). The differences in other toxicity profiles between AIs and tamoxifen did not change significantly over time.

Conclusions

The increased risk of bone fractures associated with adjuvant AIs falls over time and after discontinuation of treatment. Differences in other toxicities between AIs and tamoxifen do not change significantly over time including a persistently elevated risk of cardiovascular events.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Adjuvant endocrine therapy for early-stage hormone receptor positive breast cancer improves disease free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS) [1]. In postmenopausal women treatment with aromatase inhibitors (AIs) either as an upfront treatment or in sequence after initial tamoxifen has shown improvement in DFS and breast cancer-specific mortality [1].

In low risk patients the absolute benefit from endocrine may be modest, and as endocrine treatment may result is clinical meaningful toxicity [2, 3], decision on endocrine treatment should be tailored individually based on the clinical risk and patient’s comorbidities and preferences. Toxicity profiles of AIs and tamoxifen are different, with AIs associated with musculoskeletal symptoms, osteoporosis and an increased risk for bone fractures [4, 5]. Additionally, AIs are associated with cardiotoxicity in the initial adjuvant treatment compared to monotherapy with tamoxifen [2] as well as in the extended setting compared to placebo or no treatment [3]. Tamoxifen is associated with increased risk of thromboembolic events and a small but significant rise of the risk of endometrial cancer [2].

It is unclear if there is a change in the magnitude of toxicity of endocrine treatment over time. Here, we report on a meta-analysis evaluating the change over time of adverse events reported in phase III randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of initial endocrine treatment comparing treatment with AIs to tamoxifen in women with hormone receptor–positive early breast cancer.

Methods

Literature review and study identification

We searched MEDLINE (host: PubMed) to identify RCTs of initial adjuvant endocrine therapy comparing AIs to tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer. We based the search on a dataset of RCTs identified previously [6]. An updated search, extending to January 31, 2019 was conducted to identify later reports of these RCTs with longer duration of follow-up. Data from trials of extended adjuvant therapy were not included. The search was restricted to English language articles.

Data extraction

Data were collected independently by two reviewers (DR and HG). All data were extracted from primary publications and their associated online appendices. Collected data included year of publication, median duration of follow-up, study sample size and the treatment in the experimental and control groups. Subsequently, we extracted data from each report on pre-specified adverse events including: fractures, cardiovascular events, cerebrovascular events, thromboembolic events, secondary cancers (excluding new primary breast cancer), endometrial cancer (if reported separately from unselected secondary cancers) and death without breast cancer recurrence. The number of events and the number of women at risk were extracted for each adverse event over the different follow-up of every study. Data were extracted individually for the experimental group (comprising treatment with AIs as either upfront or in sequence to tamoxifen) and for the control group (comprising treatment with tamoxifen). In the TEAM study [7], where both groups were treated with AIs, the sequential arm which received tamoxifen followed by exemestane, was analyzed in the tamoxifen group, and the monotherapy exemestane arm was analyzed in the AI group. In order to identify the number of new events over time, we subtracted the number of events in earlier reports from those in later reports thereby estimating the number of new adverse events.

Data synthesis and statistical analysis

Odds ratios (ORs) and associated 95% confidence interval (CI) were computed for each adverse event at each time of follow-up. Data were then pooled in a meta-analysis using RevMan 5.3 (The Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark). The Pooled estimates of OR were computed using Peto one-step OR [8] when the absolute event rates in the experimental and control groups were less than 1% in all studies, otherwise the Mantel–Haenszel OR method [9] was used. ORs were computed for 2 periods: the first 5 years of treatment (using the publication closest to a median follow-up of 60 months for each study) and after completion of treatment (using the most updated publication with duration of follow-up longer 60 months). Due to substantial clinical heterogeneity between studies in the time from diagnosis to randomization and in exposure to prior treatments, analyses were performed using random effects modeling irrespective of the statistical heterogeneity. Absolute risks were calculated as the number of events over the follow-up period of individual trials divided into the total number of patients at risk in each group. The difference in absolute risk between the AIs and tamoxifen for each of the pre-defined periods was also presented as the number needed to harm (NNH), which quantifies the number of patients who would need to be treated with AIs compared to tamoxifen to cause an adverse event in one patient: positive values represent events more likely or occur with treatment with AIs while negative values represent events more likely to occur with tamoxifen.

Change in OR over time was evaluated using meta-regression which comprised a univariable linear regression weighted by individual study sample size using the weighted least squares (mixed effect) function [10]. Analyses were undertaken for all adverse events with at least 3 studies reporting data. Analyses were performed using SPSS version 25 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Due to the small number of included studies, associations were assessed quantitatively using the Burnand criteria [11] rather than inferring associations based of the p value [12, 13].

Results

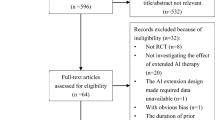

A total of 21 reports from 7 individual trials comprising 30,039 patients were identified and included in the analysis [4, 5, 7, 14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. Duration of median follow-up included reports varied from 28 to 128 months. A description of the included studies and the characteristics of the included patients in each trial are shown in Table 1. The data collection time points are illustrated in Fig. 1. For the ATAC trial, we excluded data on the combination arm of tamoxifen with anastrozole while for the BIG 1–98 trial, we included only the monotherapy arms, thereby excluding the sequential therapy arms. The long-term follow-up of the BIG 1–98 trial with a median follow-up of 12.6 years included substantially fewer patients compared to the previous publications and data on adverse events were incomplete [15], therefore this study was not included in our analysis.

Timing of data collection for individual studies. ATAC Arimidex, Tamoxifen Alone or in Combination, BIG Breast International Group, IES Intergroup Exemestane Study, ITA Italian Tamoxifen Anastrozole, TEAM The Tamoxifen Exemestane Adjuvant Multinational, ABCSG Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group, ARNO Arimidex-Nolvadex. *Data were extracted only for the monotherapy arms

The pooled ORs, 95% CIs as well as the absolute difference and the NNH for each adverse event during the duration of treatment and after completion of treatment are reported in Table 2. Overall, results were similar to a prior analysis [2]. Compared to tamoxifen, treatment with AIs was associated with increased odds of fractures and cardiovascular events. Compared to AIs, treatment with tamoxifen was associated with increased odds of thromboembolic events and endometrial cancer. All these differences were statistically significant during and after completion of treatment (Table 2). As data for cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events after completion of treatment were reported in only 2 studies, formal pooling was not performed for these adverse events. There was no significant difference in the odds of second cancers, cerebrovascular disease and death without recurrence between AIs and tamoxifen.

The results of meta-regression evaluating the change in ORs for toxicity over time are shown in Table 3. Over time there was a statistically significant reduction in the difference of bone fracture risk between AIs and tamoxifen (β = − 0.644, p = 0.01, see Fig. 2). There was a non-significant increase in the OR for secondary cancer between AIs and tamoxifen (β = + 0.448, p = 0.094, see Fig. 3). No other significant change was identified in the toxicity profiles, including cardiovascular events (β = − 0.17, p = 0.616, see Fig. 4).

Discussion

We aimed to investigate whether differences in toxicity profiles between tamoxifen and AIs evolve over the course of time in postmenopausal women receiving adjuvant hormonal therapy. Our analysis was based on data from 7 large RCTs reporting adverse effects at different follow-up points, both during and after cessation of treatment. Overall, toxicity profiles in our analysis were similar to those reported previously. Results showed increased risk of fractures and cardiovascular events with AIs treatment and increased risk of thromboembolic events and endometrial cancer with tamoxifen treatment. However, the magnitude of the increased odds of fracture with an AI in respect to tamoxifen lessened over time. Also, a non-significant decrease in the magnitude of reduced odds of secondary cancers occurred over time.

The reduction in the magnitude of increased odds of fractures could be explained in part by higher event rates in an aging population. This may attenuate the impact of treatment-related bone loss. Also, improved osteoporosis treatments and fall prevention measures may have been applied to women treated with AIs due to the known higher risk for fractures. This may have also influenced the risk of fractures.

Supporting these results are the reports from two trials which reported adverse events in the period off-treatment. In the 10 year follow-up report of the ATAC trial, serious event rates including bone fractures were similar after completion of treatment [28]. In the most updated report from the BIG 1–98 trial after median follow-up of 12.6 years there was no signal for differential risk of cerebrovascular events, osteoporosis, or fracture rates [15]. Of note, while the occurrence of myocardial infarction was similar between the AI and tamoxifen-treated women in the long-term follow-up period, there was a notable difference in the occurrence of other cardiac conditions (15 versus 43 events in the tamoxifen and the AI groups, respectively). In our analysis, the increased risk of cardiovascular disease with AIs did not diminish over time. This is helpful in the design of prevention programs. However, it is important to highlight that only two studies with long-term follow-up reported cardiovascular events. The long-term follow-up of the BIG 1–98 trial was not included in our analysis, but the difference in occurrence of other cardiac conditions [15] raises some concern about the long-term effect of AIs on cardiovascular health.

While we observed a non-significant reduction in the magnitude of the reduced odds of second cancers with AIs compared to tamoxifen, as the OR for secondary cancers was not significantly different between the AIs and tamoxifen groups, this change over time probably does not have a clinical significance.

In patients at low risk for breast cancer recurrence, the difference in toxicities can be important for selecting treatment. Different strategies for adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women are acceptable and need to be tailored for every patient based on the patient’s preferences and predicted toxicity profiles. These strategies include 5 years of AIs or a sequence of treatment with tamoxifen and AIs to complete 5 years of endocrine therapy [35]. Extended therapy with AIs for up to an additional of 5 years further reduces recurrences [36, 37], but with additional toxicity [3]. The decision to extend therapy beyond the traditional 5 years needs to be made after discussion of the benefits and risks of this treatment. Our results add additional information for consideration while choosing the most appropriate strategy per patient. Importantly, women treated with AIs remain at an increased risk of cardiovascular events compared to women treated with tamoxifen. In light of the importance of cardiovascular disease to morbidity [38] and mortality [39], these are important considerations.

Our analysis has several limitations. This is a meta-analysis based on the literature and not of individual patient data. Reporting of adverse effects was heterogeneous and the quality of such reporting is known to be inconsistent [40]. Additionally, adverse events in trials such as these are usually reported only until the primary endpoint such as breast cancer recurrence occurs. However, adverse effects after recurrences are still of interest, especially due to prolonged survival in most patients with hormone positive breast cancer even after disease recurrence. Such data were not available in the trials in this analysis. Furthermore, adverse effects may not be captured as well after completion of treatment and therefore are more likely to be under-reported in reports after longer follow-up. In the long-term follow-up of the BIG trial, differences in the adverse event reports between a national registry and clinical trial indicate that adverse events in long-term clinical trials may be under-reported [15].

Conclusion

In summary, the increased risk of bone fractures associated with adjuvant AIs falls over time and after discontinuation of treatment. Other differences in toxicity profiles between adjuvant AIs and tamoxifen do not change significantly over time including a persistently elevated risk of cardiovascular events. These findings are of interest when deciding on adjuvant endocrine treatment.

Abbreviations

- DFS:

-

Disease free survival

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- AI:

-

Aromatase inhibitors

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- NNH:

-

Number needed to harm

References

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG) (2015) Aromatase inhibitors versus tamoxifen in early breast cancer: patient-level meta-analysis of the randomised trials. Lancet 386:1341–1352. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)61074-1

Amir E, Seruga B, Niraula S, Carlsson L, Ocaña A (2011) Toxicity of adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal breast cancer patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 103:1299–1309. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djr242

Goldvaser H, Barnes TA, Seruga B, Cescon DW, Ocaña A, Ribnikar D et al (2018) Toxicity of extended adjuvant therapy with aromatase inhibitors in early breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djx141

Breast International Group (BIG) 1-98 Collaborative Group, Thürlimann B, Keshaviah A, Coates AS, Mouridsen H, Mauriac L et al (2005) A comparison of letrozole and tamoxifen in postmenopausal women with early breast cancer. N Engl J Med 353:2747–2757. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa052258

Baum M, Budzar AU, Cuzick J, Forbes J, Houghton JH, Klijn JGM et al (2002) Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early breast cancer: first results of the ATAC randomised trial. Lancet (London, England) 359:2131–2139. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(02)09088-8

Algorashi I, Goldvaser H, Ribnikar D, Cescon DW, Amir E (2018) Evolution in sites of recurrence over time in breast cancer patients treated with adjuvant endocrine therapy. Cancer Treat Rev 70:138–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctrv.2018.08.009

van de Velde CJ, Rea D, Seynaeve C, Putter H, Hasenburg A, Vannetzel J-M et al (2011) Adjuvant tamoxifen and exemestane in early breast cancer (TEAM): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet 377:321–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62312-4

Sweeting MJ, Sutton AJ, Lambert PC (2004) What to add to nothing? Use and avoidance of continuity corrections in meta-analysis of sparse data. Stat Med. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.1761

Higgins JPT, Deeks JJ (2011) Meta-analysis of rare events. In: Higgins JPT, Green S (eds) Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (version 5.1.0). Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011] The Cochrane Collaboration

Stanley TD, Doucouliagos H (2015) Neither fixed nor random: weighted least squares meta-analysis. Stat Med. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.6481

Burnand B, Kernan WN, Feinstein AR (1990) Indexes and boundaries for quantitative significance; in statistical decisions. J Clin Epidemiol 43:1273–1284

Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA (2016) The ASA Statement on p -values: context, process, and purpose. Am Stat 70:129–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2016.1154108

Wasserstein RL, Schirm AL, Lazar NA (2019) Moving to a world beyond “p > 0.05”. Am Stat 73:1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00031305.2019.1583913

Regan MM, Neven P, Giobbie-Hurder A, Goldhirsch A, Ejlertsen B, Mauriac L et al (2011) Assessment of letrozole and tamoxifen alone and in sequence for postmenopausal women with steroid hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: the BIG 1–98 randomised clinical trial at 8·1 years median follow-up. Lancet Oncol 12:1101–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70270-4

Ruhstaller T, Giobbie-Hurder A, Colleoni M, Jensen M-B, Ejlertsen B, de Azambuja E et al (2019) Adjuvant letrozole and tamoxifen alone or sequentially for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive breast cancer: long-term follow-up of the BIG 1–98 trial. J Clin Oncol 37:105–114. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.00440

Coombes RC, Hall E, Gibson LJ, Paridaens R, Jassem J, Delozier T et al (2004) A randomized trial of exemestane after two to three years of tamoxifen therapy in postmenopausal women with primary breast cancer. N Engl J Med 350:1081–1092. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa040331

Coombes R, Kilburn L, Snowdon C, Paridaens R, Coleman R, Jones S et al (2007) Survival and safety of exemestane versus tamoxifen after 2–3 years’ tamoxifen treatment (Intergroup Exemestane Study): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 369:559–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60200-1

Bliss JM, Kilburn LS, Coleman RE, Forbes JF, Coates AS, Jones SE et al (2012) Disease-related outcomes with long-term follow-up: an updated analysis of the Intergroup Exemestane Study. J Clin Oncol 30:709–717. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2010.33.7899

Morden JP, Alvarez I, Bertelli G, Coates AS, Coleman R, Fallowfield L et al (2017) Long-term follow-up of the intergroup exemestane study. J Clin Oncol 35:2507–2514. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.70.5640

Boccardo F, Rubagotti A, Puntoni M, Guglielmini P, Amoroso D, Fini A et al (2005) Switching to anastrozole versus continued tamoxifen treatment of early breast cancer: preliminary results of the Italian Tamoxifen Anastrozole Trial. J Clin Oncol 23:5138–5147. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2005.04.120

Boccardo F, Rubagotti A, Guglielmini P, Fini A, Paladini G, Mesiti M et al (2006) Switching to anastrozole versus continued tamoxifen treatment of early breast cancer. Updated results of the Italian tamoxifen anastrozole (ITA) trial. Ann Oncol. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdl941

Boccardo F, Guglielmini P, Bordonaro R, Fini A, Massidda B, Porpiglia M et al (2013) Switching to anastrozole versus continued tamoxifen treatment of early breast cancer: long term results of the Italian Tamoxifen Anastrozole trial. Eur J Cancer 49:1546–1554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.025

Aihara T, Takatsuka Y, Ohsumi S, Aogi K, Hozumi Y, Imoto S et al (2010) Phase III randomized adjuvant study of tamoxifen alone versus sequential tamoxifen and anastrozole in Japanese postmenopausal women with hormone-responsive breast cancer: N-SAS BC03 study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-010-0888-x

Aihara T, Yokota I, Hozumi Y, Aogi K, Iwata H, Tamura M et al (2014) Anastrozole versus tamoxifen as adjuvant therapy for Japanese postmenopausal patients with hormone-responsive breast cancer: efficacy results of long-term follow-up data from the N-SAS BC 03 trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat 148:337–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-014-3155-8

Derks MGM, Blok EJ, Seynaeve C, Nortier JWR, Kranenbarg EMK, Liefers GJ et al (2017) Adjuvant tamoxifen and exemestane in women with postmenopausal early breast cancer (TEAM): 10-year follow-up of a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 18:1211–1220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30419-9

Jakesz R, Jonat W, Gnant M, Mittlboeck M, Greil R, Tausch C et al (2005) Switching of postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer to anastrozole after 2 years’ adjuvant tamoxifen: combined results of ABCSG trial 8 and ARNO 95 trial. Lancet (London, England) 366:455–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67059-6

Dubsky PC, Jakesz R, Mlineritsch B, Pöstlberger S, Samonigg H, Kwasny W et al (2012) Tamoxifen and anastrozole as a sequencing strategy: a randomized controlled trial in postmenopausal patients with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer from the Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group. J Clin Oncol 30:722–728. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2011.36.8993

Cuzick J, Sestak I, Baum M, Buzdar A, Howell A, Dowsett M et al (2010) Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 10-year analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 11:1135–1141. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70257-6

Baum M, Buzdar A, Cuzick J, Forbes J, Houghton J, Howell A et al (2003) Anastrozole alone or in combination with tamoxifen versus tamoxifen alone for adjuvant treatment of postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer. Cancer 98:1802–1810. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.11745

Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination Trialists’ Group, Buzdar A, Howell A, Cuzick J, Wale C, Distler W et al (2006) Comprehensive side-effect profile of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: long-term safety analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 7:633–643. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70767-7

Howell A, Cuzick J, Baum M, Buzdar A, Dowsett M, Forbes JF et al (2005) Results of the ATAC (Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination) trial after completion of 5 years’ adjuvant treatment for breast cancer. Lancet 365:60–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17666-6

Arimidex, Tamoxifen, Alone or in Combination (ATAC) Trialists’ Group, Forbes JF, Cuzick J, Buzdar A, Howell A, Tobias JS et al (2008) Effect of anastrozole and tamoxifen as adjuvant treatment for early-stage breast cancer: 100-month analysis of the ATAC trial. Lancet Oncol 9:45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(07)70385-6

BIG 1-98 Collaborative Group, Mouridsen H, Giobbie-Hurder A, Goldhirsch A, Thürlimann B, Paridaens R et al (2009) Letrozole therapy alone or in sequence with tamoxifen in women with breast cancer. N Engl J Med 361:766–776. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0810818

Coates AS, Keshaviah A, Thürlimann B, Mouridsen H, Mauriac L, Forbes JF et al (2007) Five years of letrozole compared with tamoxifen as initial adjuvant therapy for postmenopausal women with endocrine-responsive early breast cancer: update of Study BIG 1–98. J Clin Oncol 25:486–492. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2006.08.8617

Gradishar WJ, Abraham J, Aft R, Agnese D, Allison KH, Blair SL, et al (2019) NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2019 Breast Cancer NCCN Guidelines Panel Disclosures Continue † Medical oncology ¶ Surgery/Surgical oncology § Radiation oncology/Radiotherapy ≠ Pathology ‡ Hematology/Hematology oncology ф Diagnostic/Interventional radiology ¥ Patient advocate Þ Internal medicine Ÿ Reconstructive surgery *Discussion Section Writing Committee

Goss PE, Ingle JN, Pritchard KI, Robert NJ, Muss H, Gralow J et al (2016) Extending aromatase-inhibitor adjuvant therapy to 10 years. N Engl J Med 375:209–219. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1604700

Jakesz R, Greil R, Gnant M, Schmid M, Kwasny W, Kubista E et al (2007) Extended adjuvant therapy with anastrozole among postmenopausal breast cancer patients: results from the randomized Austrian Breast and Colorectal Cancer Study Group Trial 6a. J Natl Cancer Inst 99:1845–1853. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djm246

Abdel-Qadir H, Thavendiranathan P, Austin PC, Lee DS, Amir E, Tu JV et al (2019) The risk of heart failure and other cardiovascular hospitalizations after early stage breast cancer: a matched cohort study. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst 111:854–862. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djy218

Abdel-Qadir H, Austin PC, Lee DS, Amir E, Tu JV, Thavendiranathan P et al (2017) A population-based study of cardiovascular mortality following early-stage breast cancer. JAMA Cardiol 2:88. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2016.3841

Liauw WS, Day RO (2003) Adverse event reporting in clinical trials: room for improvement. Med J Aust 179:426

Funding

This research did not receive any specific Grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the work: DR EA HG; Acquisition of data: DR HG; Analysis and interpretation of data: DR RY AM AD RS EA HG Wrote the manuscript with input from all authors: DR HG; All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Dr. Yerushalmi reports personal fees from: Roche (Consulting, Invited speaker), Pfizer (Consulting), Novartis (Consulting), Teva (Invited speaker), Medison (Invited speaker), MSD (Invited speaker), Astra-Zeneca (Invited speaker) and Novartis (Invited speaker), all outside the submitted work. Dr. Moore reports honorarium fees from MSD and Roche, all outside the submitted work. Dr. Amir reports personal fees from Genentech/Roche (Expert Testimony), personal fees from Apobiologix (Consulting), personal fees from Myriad Genetics (Consulting), personal fees from Agendia (Consulting), personal fees from Sandoz (Consulting), all outside the submitted work. Dr. Goldvaser reports personal fees from: Roche (honorarium), Pfizer (honorarium), Novartis (honorarium and consulting) all outside the submitted work. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Reinhorn, D., Yerushalmi, R., Moore, A. et al. Evolution in the risk of adverse events of adjuvant endocrine therapy in postmenopausal women with early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 182, 259–266 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05715-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-020-05715-1