Abstract

Interactive toxicity beliefs regarding mixing alcohol and antiretroviral therapy (ART) may influence ART adherence. HIV-infected patients in Uganda completed quarterly visits for 1 year, or one visit at 6 months, depending on study randomization. Past month ART non-adherence was less than daily or <100 % on a visual analog scale. Participants were asked if people who take alcohol should stop taking their medications (belief) and whether they occasionally stopped taking their medications in anticipation of drinking (behavior). Visits with self-reported alcohol use and ART use for ≥30 days were included. We used logistic regression to examine correlates of the interactive toxicity belief and behavior, and to determine associations with ART non-adherence. 134 participants contributed 258 study visits. The toxicity belief was endorsed at 24 %, the behavior at 15 %, and any non-adherence at 35 % of visits. In multivariable analysis, the odds of non-adherence were higher for those endorsing the toxicity behavior [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 2.06; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.97–4.36] but not the toxicity belief (AOR 0.63; 95 % CI 0.32–1.26). Clear messaging about maintaining adherence, even if drinking, could benefit patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

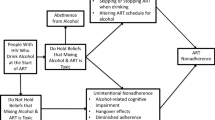

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) can dramatically improve the health and lives of those infected with HIV and lead to viral suppression. However, the efficacy of ART depends upon treatment adherence; the minimum level of ART adherence needed to achieve HIV viral suppression varies by ART class [1]. Various factors are recognized to be barriers to ART adherence, including lack of social support, being unmarried, depression, HIV stigma, food insecurity, transportation cost and time to clinic, and alcohol use [2–9]. Alcohol use in particular has been found to be associated with missed doses and treatment interruptions [10–12]. One possible explanation for the consistent association observed between alcohol use and poor adherence may be explained by alcohol myopia theory, the idea that acute alcohol use causes short-sightedness, and can cause users to focus on and respond primarily to their immediate environment [13], leading to unintentional non-adherence. However, a phenomenon termed interactive toxicity beliefs may be another important cause of reduced ART adherence among drinkers. Interactive toxicity beliefs are the beliefs that mixing alcohol and ART is toxic, and endorsing such beliefs may lead patients to purposefully alter their medication adherence while they are drinking alcohol, or when they plan to drink.

A small number of studies have described alcohol toxicity beliefs and their impact on HIV outcomes among people living with HIV in the United States. In a pilot study in Florida, 20 % of participants reported “weekending” (drinking more alcohol on weekends, and intentionally skipping 1 or 2 days of ART due to drinking plans) [14]. Sankar et al. [15] found that most (85 %) participants believed that alcohol and ART shouldn’t be mixed; 51 % reported that they wouldn’t take their medications if they had been drinking alcohol. Similarly, Kalichman et al. [16] found interactive toxicity beliefs to be common among HIV-positive drinkers and non-drinkers in Georgia. They found that stopping ART while drinking alcohol was associated with non-adherence, after adjusting for scores on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) and demographics. In a longitudinal study of HIV-infected drinkers, half of the participants reported skipping or stopping their HIV medications while drinking. Those that endorsed interactive toxicity beliefs were more likely to have poor adherence on drinking days [17].

Interactive toxicity beliefs in settings other than the US have been less studied, thus far. In a qualitative study among HIV-positive adults new to HIV care in Uganda, however, it was common for participants to describe being told by clinic staff that alcohol and ART “don’t mix”, and that alcohol weakens the effect of ART [18]. In a qualitative study of determinants of adherence among patients on ART for at least 6 months in Tanzania [19], alcohol use was commonly reported as a reason for both unintentional and intentional non-adherence. Among HIV-infected drinkers in South Africa, several patterns of taking ART were reported when drinking, including taking ART early, taking ART as scheduled, and skipping ART, with about half of the participants reporting a combination of these ART use patterns on drinking days [20]. Reasons for the different adherence patterns, however, were not assessed. As such, it appears that the patterns of ART use among HIV-positive adults in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) may be altered, both unintentionally and intentionally, by drinking. Additionally, there is some evidence from the two qualitative studies noted above that alcohol interactive toxicity beliefs may be common. However, the specific associations between participant alcohol interactive toxicity beliefs and medication adherence have yet to be examined in SSA.

The purpose of this study was to: (1) determine the prevalence of interactive toxicity beliefs and behaviors, (2) describe the correlates of these, and (3) examine whether they were associated with self-reported ART non-adherence, in a longitudinal study of HIV-infected adult drinkers new to HIV care in Uganda. We hypothesized that endorsement of the interactive toxicity belief and behavior would be associated with ART non-adherence among our study participants.

Methods

Study Population

The Biomarker Research on Ethanol Among Those with HIV (BREATH) Study was a mixed methods study of changes in alcohol consumption during the first year of HIV care. New adult patients attending the Immune Suppression Syndrome (ISS) Clinic in Mbarara, Uganda, were invited to participate. Eligibility criteria included: age ≥18 years old, fluency in English or Runyakole (the local language), residence within 60 km of the clinic, being new to the ISS Clinic and HIV care, and either self-reporting alcohol consumption within the past year, or being suspected of recent alcohol consumption by the clinic counselor (<1 % of participants).

Participants were randomized to one of two study arms: the main cohort study arm, or a minimally assessed study arm designed to examine assessment reactivity [21]. Those randomized to the main cohort arm completed structured quantitative interviews quarterly for 1 year; a sub-set of these participants also completed qualitative interviews every 6 months during this year [18]. Participants randomized to the minimally assessed arm were interviewed only once, 6 months following study enrollment. At each study visit, participants completed an interviewer-administered structured interview, and underwent breath alcohol concentration testing and phlebotomy. There is no systematic protocol in place for alcohol interventions in this setting; however, if a study participant scored ≥20 on the AUDIT (indicative of probable dependent alcohol use) [22], requested additional help decreasing their alcohol consumption, endorsed suicidal ideation on the survey (“thoughts of ending your life”), or seemed especially distressed during their study interview, they were referred to a mental health counselor in the Psychiatry Department of Mbarara Regional Referral Hospital for care. Study participants engaged in HIV clinical care, including initiating ART, independently of study activities. All study procedures were approved by Institutional Review Boards at the University of California San Francisco, the Mbarara University of Science and Technology (MUST), and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology.

Laboratory Measurements

Specimens were collected for HIV viral load concurrently with the first study interview (Bayer System 340 bDNA analyzer; Bayer Healthcare Corporation, Whippany, NJ), and for CD4+ cell count at baseline, 6-, and 12-month visits (Coulter Epics XL.MCL Cytometer; Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). CD4 count and viral load testing were conducted at the MUST Clinical and Research Laboratory.

Specimens were also collected for phosphatidylethanol (PEth) testing at each study visit. PEth is a phospholipid which forms only in the presence of alcohol; it has been shown to be highly sensitive and specific for any and heavy alcohol use among persons with HIV in Uganda [23]. Venous blood samples were collected from participants by clinic staff at each study visit, and transferred to dried blood spot (DBS) cards by laboratory staff. DBS cards were stored at −80 °C at the MUST Clinical and Research Laboratory until they were shipped to the United States Drug Testing Laboratories, Inc. (USDTL), where they were tested for PEth using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) following extraction into methanol [24]. The lower limit of detection was 8 ng/ml, and the most common PEth homologue (16:0/18:1) was detected.

Variables

ART Non-adherence

There is currently no gold standard for measuring or defining ART non-adherence [25]. In our study, any ART non-adherence was defined using self-report. Self-reported adherence is thought to be an over-report of actual adherence [26–28], thus we chose to use a conservative definition of any ART non-adherence. As such, any self-reported ART non-adherence in the past 30 days was defined using a composite variable made from the following questions regarding ART adherence, asked at each study visit: (1) “In the past 30 days, did you take all your anti-HIV pills every day?”; (2) “In the past 30 days, how many days, in total, have you not taken your anti-HIV medication pills?”; (3) Using a visual analog adherence scale, participants were asked, on a scale from 0 to 100 (100 = all doses), to indicate how many of their ART doses they took in the past 30 days [29]. Participants who reported not taking their ART on every day, or reported <100 on the adherence scale, were considered to be non-adherent in the past 30 days at that visit. We also asked participants if they were unable to get their ART in the past 3 months because the pharmacy was out of pills; participants that replied yes to this question (n = 5) were excluded from our measure of non-adherence (set to missing).

Interactive Toxicity Items

At each visit, participants were asked questions regarding mixing alcohol use and medications. We modified questions from Kalichman et al. [16], instructing participants to consider co-trimoxazole, multivitamins, and ART as medications, and simplifying the language for ease of translation into the local language. For this analysis, we focused on two of these questions, one an interactive toxicity “belief”: “I think that people who take alcohol should stop taking their medications because they should not mix them”, and the other a “behavior”: “I occasionally stop taking any medications I am on if I think I will be drinking alcohol”. Response options were true, false, or not applicable.

Covariates

We included participant demographics, as well as factors found to be associated with ART adherence or interactive toxicity beliefs, in this analysis.

Demographics

We examined demographic characteristics including sex, age, religion/denomination, education, marital status, and social support, and household characteristics including household assets, food insecurity, and travel time to the clinic. Perceived social support was measured using a modified version of the Duke-UNC Functional Social Support Scale [30] (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89); a mean score <3 was considered “low social support”. The household asset index was created using principal components analysis, and grouped participants’ households based on ownership of durable goods, housing quality, and available energy sources [31, 32]. The bottom 40 % was considered low, the middle 40 % as middle, and the top 20 % as high. The Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) was used to assess food insecurity [33, 34] (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.94); participants were categorized into three groups (food secure, mildly/moderately insecure, severely insecure) for analysis due to small numbers in the mildly insecure food access group. Participants were asked how long it takes to travel from their home to the ISS Clinic; we created four groups (0–20, 21–40, 41–60, >60 min).

Mental and Physical Health Status and Clinical Contact

General health status was assessed using the first question of the Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV) at each study visit [35, 36]. While the MOS-HIV has been shown to be a valid measure of health in Uganda, the first question (“In general, would you say your health is excellent, very good, good, fair or poor?”) has not been validated among people with HIV. However, this single item has been shown to predict mortality and healthcare utilization as well as multi-item scales among Veterans Administration outpatients in the US [37]. As such, we chose to use this single item as an indicator of general health status, and dichotomized responses as excellent/very good/good versus fair/poor. Depressive symptoms were assessed using a modified 16-item version of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist that has been validated for use in persons with HIV in Uganda [38–40] (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.90). As inclusion of somatic symptoms has been shown to inflate depression scores among HIV-infected people, we chose to exclude the four somatic items (“feeling low in energy, slowed down,” “feeling fidgety,” “poor appetite,” and “having difficulty falling or staying asleep”) for our analyses [41–43]. Cronbach’s alpha for the 12-item version of this scale in our study was 0.87. The total 12-item score was then averaged; participants with a score of 1.75 or more were classified as having symptoms of probable depression. We created a variable to indicate the number of clinic visits in the past 3 months, retrieved from the MUST ISS Clinic electronic medical records.

Alcohol Use

Alcohol use was assessed at each visit, using both self-report and PEth. We used the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C), a 3-item scale with a total score ranging from 0 to 12 [44, 45], to classify participants as self-reported non-drinkers (AUDIT-C = 0), self-reported low risk drinkers (AUDIT-C = 1–3 for men, 1–2 for women), or self-reported unhealthy drinkers (“AUDIT-C positive”: AUDIT-C ≥4 for men, ≥3 for women) in the past 3 months. Because we have previously observed under-reporting of alcohol use in this population [46–48], we created a composite variable to better capture any unhealthy use using both self-report and PEth. Combining two measures with high specificity improves the sensitivity of the measure, compared to using either measure alone [49]. As such, unhealthy alcohol use was defined as a positive AUDIT-C score, or PEth ≥50 ng/ml. This PEth cutoff for unhealthy alcohol use was highly sensitive (93 %) and reasonably specific (83 %) for detecting average daily drinking of at least 2 drinks per day in a study of 222 patients with liver disease (S. Stewart, personal communication); another study among 80 reproductive age women showed a cutoff of 45 ng/ml had 61 % sensitivity and 95 % specificity for the same level of drinking [50].

Analysis

All analyses were limited to visits at which the participants reported taking ART for at least 30 days. We also limited the analyses to those visits in which the participant reported consuming any alcohol in the prior 3 months, because (1) we felt that the responses about adherence and interactive toxicity would be more accurate among those reporting recent alcohol use in a population in which we have observed socially desirable reporting, and (2) perceptions of the toxicity of mixing ART and drinking are most relevant to current drinkers. To describe the participants included in our analyses, we calculated frequency distributions for categorical variables and medians and inter-quartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables.

We described endorsement (response choice = true) of the interactive toxicity items at each study visit using bivariate generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic regression models for both items separately, with robust standard errors and exchangeable working correlations.

To analyze ART non-adherence, we conducted bivariate and multivariable GEE logistic regression models of non-adherence, using robust standard errors and exchangeable working correlations. We used a purposeful selection approach to create the multivariable model [51]; both interactive toxicity items were forced into the multivariable model. Covariates were initially included if they were associated with ART non-adherence, or either of the interactive toxicity items, in bivariate analyses at a p value ≤0.25. They were then excluded in a backwards stepwise manner, until all remaining variables were associated at p ≤ 0.10. Next, any covariates initially excluded based on the p value ≤0.25 cut-off were individually added into the model, and their significance re-assessed; they were retained if they were associated at p ≤ 0.10. This process continued iteratively until no new covariates were added or removed.

Results

Participant Characteristics

A total of 205 participants were enrolled in the main BREATH Study cohort, and 141 participants were enrolled in the minimally assessed comparison arm and completed their study interview at 6 months, for a total of 346. Of these participants, 215 were on ART for 30 days during at least one study interview and 134 of those admitted to any alcohol consumption in the prior 3 months. These 134 participants were on ART and reported any alcohol use in 258 follow-up visits, which were included in these analyses. 53 % of participants completed 1 visit, 16 % completed 2 visits, 16 % completed 3 visits, and 15 % completed 4 visits.

Forty-nine of the participants (37 %) were female, slightly more than half were married (55 %), and 38 % had more than a primary education (Table 1). The median age was 31 years (IQR 26–37).

At the first study interview following ART initiation, 9 % screened positive for symptoms of depression in the past 3 months, and 13 % reported their health status as fair or poor. Eighty-five (63 %) were positive for unhealthy alcohol use.

Interactive Toxicity Items

At approximately one-fourth (24 %) of visits, participants endorsed the interactive toxicity belief; participants endorsed the interactive toxicity behavior at 15 % of visits. Participants endorsed both items at 8 % of visits. In bivariate analyses, the odds of endorsement for each item were higher with increasing age, although the association with the belief did not reach statistical significance (Wald χ2 = 4.74; p value = 0.09) (Table 2). The odds of endorsing the interactive toxicity belief were increased for those with a higher number of clinic visits in the past 3 months (Wald χ2 = 5.02; p value = 0.03), and were higher for participants with low perceived social support (Wald χ2 = 4.74; p value = 0.03). The odds of endorsing the interactive toxicity behavior were significantly higher among those with a higher household asset index (Wald χ2 = 6.16; p value = 0.05), and for Catholic participants (compared to Protestants) (Wald χ2 = 4.17; p value = 0.04), and lower for those with longer travel times to the clinic (Wald χ2 = 8.10; p value = 0.04). There were no statistically significant associations between any of the other covariates included and endorsement of these interactive toxicity items in our study.

ART Non-adherence

Over all visits included here (n = 258 visits), any ART non-adherence was reported at 88 visits (35 %). Among visits where participants reported missing their ART on at least 1 day in the past 30 days (n = 62), the median number of days not taking ART was 2 (IQR 1–3).

In bivariate analysis, the odds of any ART non-adherence were higher for those endorsing the interactive toxicity behavior (odds ratio (OR) 1.60; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 0.84–3.02), and lower for those endorsing the interactive toxicity belief (OR 0.76; 95 % CI 0.42–1.39); these associations were not statistically significant (Table 3). The odds of non-adherence were higher for those with recent unhealthy alcohol use (OR 1.92; 95 % CI 1.10–3.33), for unmarried participants (OR 2.04; 95 % CI 1.14–3.66), and for those with symptoms of depression (OR 2.13; 95 % CI 0.81–5.63) (not statistically significant). No other variables were associated with non-adherence in bivariate analysis.

In multivariable analysis, participants who endorsed the interactive toxicity behavior had increased odds of any ART non-adherence at that visit, compared to those who did not [adjusted OR (AOR) 2.06; 95 % CI 0.97–4.36] (Table 3). The odds of any ART non-adherence were lower for those endorsing the interactive toxicity belief (AOR 0.63; 95 % CI 0.32–1.26), and higher for participants with unhealthy alcohol use in the past 3 months (AOR 1.75; 95 % CI 0.99–3.08) and for unmarried compared to married participants (AOR 2.04; 95 % CI 1.13–3.69). No other covariates were retained in the final multivariable model.

Discussion

We found endorsement of the interactive toxicity items to be relatively common among persons with HIV who are new to HIV care and ART. Current self-reported drinkers agreed that people should stop taking their ART if they will be drinking at 24 % of their study visits. A lower proportion reported skipping ART themselves when they thought they would be drinking (15 % of study visits). The proportion believing that alcohol should not be mixed with ART is similar to the percent of alcohol users in a US study, who reported that they believed people should stop their ART while drinking (25 %) [16]; however, the proportion reporting they stopped taking ART when they were drinking is somewhat lower than in other studies among current drinkers in the US, in which the prevalence of various interactive toxicity behaviors reported ranged from approximately 20–45 % [14, 17]. The clinical implication is that HIV clinic staff in similar settings should be aware that these beliefs are not rare, and that sometimes patients do stop taking their medications when they are drinking alcohol. Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs), the most common backbone of antiretrovirals used in SSA, are quite safe with little hepatotoxicity [52–54], and patients should not stop their ART when drinking. It was common for health care providers to stress abstinence from alcohol in the qualitative sub-study of the BREATH Study, and that alcohol and ART don’t mix [18]. Participants who had attended the clinic more frequently in the 3 months prior to the study interview had increased odds of endorsing the interactive toxicity belief at that visit; frequent receipt of this messaging at clinic visits may have led participants to be more likely to retain and believe this idea that alcohol and ART don’t mix. More discussion and advice around decreasing alcohol use (rather than exclusively focusing on abstinence), as well as tools for maintaining high levels of adherence even if drinking, may be warranted and beneficial for patients.

Any ART non-adherence in our study was common using our conservative measure of any non-adherence; non-adherence was reported at 35 % of visits. However, the overall number of days missed was low; among visits in which ART was reported missing for at least 1 day in the past 30 days, the median number of days missed was 2 (IQR 1–3). Reporting the interactive toxicity behavior was associated with an increased odds of any ART non-adherence (Wald χ2 = 3.55; p value = 0.06). This suggests that beliefs about toxicity could impact ART adherence.

Similar to other studies [2, 5, 6], unhealthy alcohol use was also associated with ART non-adherence in our multivariable model, although it did not reach statistical significance (Wald χ2 = 3.72; p value = 0.054). This independent effect suggests that alcohol use may impact adherence in multiple ways, i.e. via alcohol myopia theory, and via interactive toxicity beliefs. Our unhealthy alcohol use variable consisted of self-report supplemented by a biomarker of recent alcohol use, making it an objective measure of recent unhealthy alcohol use.

Also similar to other studies [7, 8, 55], we observed a strong independent association between marital status and non-adherence; married participants were less likely to report non-adherence. While we did not find an association with our more formal social support measure, spouses may provide support and encouragement for their partner, leading to improved adherence.

This study had some limitations. First, with the exception of unhealthy alcohol use, all the behavioral variables were elicited by self-report. As described earlier, self-reported adherence is thought to be an over-report of true adherence [26–28]. Due to this, and based on our previous experience detecting socially desirable under-reporting of alcohol use in this population, our definition of any ART non-adherence in the past 30 days was very conservative. We used this definition in an attempt to minimize the effect of over-reporting adherence; however, patients new to ART are likely to be highly motivated to improve their health, and thus adherence may truly be quite high. In addition, we limited our analyses to only those participants who self-reported recent alcohol use, and thus we may have excluded an important group of participants—those drinkers who do not admit to recent use. Among the visits excluded because participants denied drinking (n = 216 visits), 42 % were PEth-positive (PEth ≥8 ng/ml), indicative of recent use. When these 90 visits were included in the model of non-adherence, the interactive toxicity results did not change substantially. However, we believed that participants who under-report alcohol use might not honestly report on their interactive toxicity beliefs or their ART adherence. Our finding that interactive toxicity beliefs were reported at a higher number of visits (24 %) than those where participants reported themselves ceasing medications while drinking (15 %) suggests that these behaviors may have been under-reported. As mentioned earlier, in the qualitative sub-study of the BREATH Study, it was common for participants to describe medical providers telling them that ART and alcohol “don’t mix” [18]; as such, participants may have been hesitant to report stopping their ART to consume alcohol themselves. An additional limitation of the study was inclusion of scales not validated for use in our particular study population; however, we felt it was appropriate and necessary to make scales culturally relevant for our study setting. The internal consistency of these scales was high, indicating good scale reliability. Similarly, using single questions to assess the interactive toxicity items, and rate general health status, may have oversimplified these measures. However, other studies have assessed interactive toxicity beliefs as single items [16], and the general health question has been shown to perform as well as multi-item scales [37].

In summary, we found beliefs regarding the interactive toxicity of alcohol use and ART, as well as the prevalence of incomplete ART adherence, to be relatively common among self-reported drinkers who were on ART for at least 1 month. We found endorsement of the interactive toxicity behavior item, as well as unhealthy alcohol use, to be related to non-adherence. It would be beneficial for patients to receive clear messaging and education about the harms associated with alcohol use, including how to decrease unhealthy levels of drinking, as well as how to maintain adherence even when drinking.

References

Kobin AB, Sheth NU. Levels of adherence required for virologic suppression among newer antiretroviral medications. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(3):372–9.

Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, Simoni JM. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(2):180–202.

Morojele NK, Kekwaletswe CT, Nkosi S. Associations between alcohol use, other psychosocial factors, structural factors and antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence among South African ART recipients. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(3):519–24.

Katz IT, Ryu AE, Onuegbu AG, et al. Impact of HIV-related stigma on treatment adherence: systematic review and meta-synthesis. J Int AIDS Soc. 2013;16(3 Suppl 2):18640.

Denison JA, Koole O, Tsui S, et al. Incomplete adherence among treatment-experienced adults on antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania, Uganda and Zambia. AIDS. 2015;29(3):361–71.

Weiser SD, Palar K, Frongillo EA, et al. Longitudinal assessment of associations between food insecurity, antiretroviral adherence and HIV treatment outcomes in rural Uganda. AIDS. 2014;28(1):115–20.

Byakika-Tusiime J, Oyugi JH, Tumwikirize WA, Katabira ET, Mugyenyi PN, Bangsberg DR. Adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy in HIV + Ugandan patients purchasing therapy. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16(1):38–41.

Teshome W, Belayneh M, Moges M, et al. Who takes the medicine? Adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Southern Ethiopia. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:1531–7.

Belenky NM, Cole SR, Pence BW, Itemba D, Maro V, Whetten K. Depressive symptoms, HIV medication adherence, and HIV clinical outcomes in Tanzania: a prospective, observational study. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e95469.

Parsons JT, Rosof E, Mustanski B. The temporal relationship between alcohol consumption and HIV-medication adherence: a multilevel model of direct and moderating effects. Health Psychol. 2008;27(5):628–37.

Braithwaite RS, McGinnis KA, Conigliaro J, et al. A temporal and dose-response association between alcohol consumption and medication adherence among veterans in care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(7):1190–7.

Conen A, Wang Q, Glass TR, et al. Association of alcohol consumption and HIV surrogate markers in participants of the swiss HIV cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;64(5):472–8.

Steele CM, Josephs RA. Alcohol myopia. Its prized and dangerous effects. Am Psychol. 1990;45(8):921–33.

Kenya S, Chida N, Jones J, Alvarez G, Symes S, Kobetz E. Weekending in PLWH: alcohol use and ART adherence, a pilot study. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):61–7.

Sankar A, Wunderlich T, Neufeld S, Luborsky M. Sero-positive African Americans’ beliefs about alcohol and their impact on anti-retroviral adherence. AIDS Behav. 2007;11(2):195–203.

Kalichman SC, Amaral CM, White D, et al. Prevalence and clinical implications of interactive toxicity beliefs regarding mixing alcohol and antiretroviral therapies among people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23(6):449–54.

Kalichman SC, Grebler T, Amaral CM, et al. Intentional non-adherence to medications among HIV positive alcohol drinkers: prospective study of interactive toxicity beliefs. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(3):399–405.

Sundararajan R, Wyatt MA, Woolf-King S, et al. Qualitative study of changes in alcohol use among HIV-infected adults entering care and treatment for HIV/AIDS in rural southwest Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(4):732–41.

Lyimo RA, de Bruin M, van den Boogaard J, Hospers HJ, van der Ven A, Mushi D. Determinants of antiretroviral therapy adherence in northern Tanzania: a comprehensive picture from the patient perspective. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:716.

Kekwaletswe CT, Morojele NK. Patterns and predictors of antiretroviral therapy use among alcohol drinkers at HIV clinics in Tshwane, South Africa. AIDS Care. 2014;26(Suppl 1):S78–82.

Hahn JA, Emenyonu N, Fatch R, Muyindike WR, Kekibiina A, Woolf-King S. Randomized study of assessment reactivity in persons with HIV in rural Uganda measured using self-report and phosphatidylethanol. In: Research Society on Alcoholism; San Antonio, TX2015.

Babor T, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders J, Monteiro M. AUDIT. The alcohol use disorders identification test. Guidelines for use in primary care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001.

Hahn JA, Dobkin LM, Mayanja B, et al. Phosphatidylethanol (PEth) as a biomarker of alcohol consumption in HIV-positive patients in sub-Saharan Africa. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(5):854–62.

Jones J, Jones M, Plate C, Lewis D. The detection of 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanol in human dried blood spots. Anal Methods. 2011;3(5):1101–6.

Williams AB, Amico KR, Bova C, Womack JA. A proposal for quality standards for measuring medication adherence in research. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(1):284–97.

Thirumurthy H, Siripong N, Vreeman RC, et al. Differences between self-reported and electronically monitored adherence among patients receiving antiretroviral therapy in a resource-limited setting. AIDS. 2012;26(18):2399–403.

Arnsten JH, Demas PA, Farzadegan H, et al. Antiretroviral therapy adherence and viral suppression in HIV-infected drug users: comparison of self-report and electronic monitoring. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33(8):1417–23.

Liu H, Golin CE, Miller LG, et al. A comparison study of multiple measures of adherence to HIV protease inhibitors. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134(10):968–77.

Simoni JM, Kurth AE, Pearson CR, Pantalone DW, Merrill JO, Frick PA. Self-report measures of antiretroviral therapy adherence: a review with recommendations for HIV research and clinical management. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):227–45.

Antelman G, Smith Fawzi MC, Kaaya S, et al. Predictors of HIV-1 serostatus disclosure: a prospective study among HIV-infected pregnant women in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. AIDS. 2001;15(14):1865–74.

Vyas S, Kumaranayake L. Constructing socio-economic status indices: how to use principal components analysis. Health Policy Plan. 2006;21(6):459–68.

Filmer D, Pritchett LH. Estimating wealth effects without expenditure data–or tears: an application to educational enrollments in states of India. Demography. 2001;38(1):115–32.

Coates J, Swindale A, Bilinsky P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of food access: indicator guide (v. 3). Washington, DC: Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development; 2007.

Frongillo EA, Nanama S. Development and validation of an experience-based measure of household food insecurity within and across seasons in northern Burkina Faso. J Nutr. 2006;136(5):1409S–19S.

Wu AW, Revicki DA, Jacobson D, Malitz FE. Evidence for reliability, validity and usefulness of the Medical Outcomes Study HIV Health Survey (MOS-HIV). Qual Life Res. 1997;6(6):481–93.

Stangl AL, Bunnell R, Wamai N, Masaba H, Mermin J. Measuring quality of life in rural Uganda: reliability and validity of summary scores from the medical outcomes study HIV health survey (MOS-HIV). Qual Life Res. 2012;21(9):1655–63.

DeSalvo KB, Fan VS, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Predicting mortality and healthcare utilization with a single question. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(4):1234–46.

Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Rickels K, Uhlenhuth EH, Covi L. The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): a self-report symptom inventory. Behav Sci. 1974;19(1):1–15.

Bolton P. Cross-cultural validity and reliability testing of a standard psychiatric assessment instrument without a gold standard. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189(4):238–42.

Bolton P, Ndogoni L. Cross-cultural assessment of trauma-related mental illness (Phase II). A report of research conducted by World Vision Uganda and The Johns Hopkins University: The Johns Hopkins University, World Vision Uganda, USAID 2001.

Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M. Distinguishing between overlapping somatic symptoms of depression and HIV disease in people living with HIV-AIDS. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2000;188(10):662–70.

Kalichman SC, Sikkema KJ, Somlai A. Assessing persons with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection using the Beck Depression Inventory: disease processes and other potential confounds. J Pers Assess. 1995;64(1):86–100.

Tsai AC, Bangsberg DR, Frongillo EA, et al. Food insecurity, depression and the modifying role of social support among people living with HIV/AIDS in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(12):2012–9.

Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP). Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–95.

Bradley KA, DeBenedetti AF, Volk RJ, Williams EC, Frank D, Kivlahan DR. AUDIT-C as a brief screen for alcohol misuse in primary care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31(7):1208–17.

Bajunirwe F, Haberer JE, Boum Y 2nd, et al. Comparison of self-reported alcohol consumption to phosphatidylethanol measurement among HIV-infected patients initiating antiretroviral treatment in southwestern Uganda. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(12):e113152.

Hahn JA, Fatch R, Kabami J, et al. Self-report of alcohol use increases when specimens for alcohol biomarkers are collected in persons with HIV in Uganda. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;61(4):e63–4.

Hahn JA, Emenyonu NI, Fatch R, et al. Declining and rebounding unhealthy alcohol consumption during the first year of HIV care in rural Uganda, using phosphatidylethanol to augment self-report. Addiction. 2016;111(2):272–9.

Marshall R. The predictive value of simple rules for combining two diagnostic tests. Biometrics. 1989;45(4):1213–22.

Stewart SH, Law TL, Randall PK, Newman R. Phosphatidylethanol and alcohol consumption in reproductive age women. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(3):488–92.

Bursac Z, Gauss CH, Williams DK, Hosmer DW. Purposeful selection of variables in logistic regression. Source Code Biol Med. 2008;3:17.

Chu KM, Manzi M, Zuniga I, et al. Nevirapine- and efavirenz-associated hepatotoxicity under programmatic conditions in Kenya and Mozambique. Int J STD AIDS. 2012;23(6):403–7.

Ocama P, Castelnuovo B, Kamya MR, et al. Low frequency of liver enzyme elevation in HIV-infected patients attending a large urban treatment centre in Uganda. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21(8):553–7.

Osakunor DN, Obirikorang C, Fianu V, Asare I, Dakorah M. Hepatic enzyme alterations in HIV patients on antiretroviral therapy: a case-control study in a hospital setting in Ghana. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0134449.

Bhat VG, Ramburuth M, Singh M, et al. Factors associated with poor adherence to anti-retroviral therapy in patients attending a rural health centre in South Africa. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2010;29(8):947–53.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the BREATH Study participants for their time and participation, and the BREATH Study team members for their hard work and dedication.

Funding

This work was funded by the US National Institutes of Health, Grants R01AA018631, U01AA020776, and K24AA022586.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no known conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors. All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fatch, R., Emenyonu, N.I., Muyindike, W. et al. Alcohol Interactive Toxicity Beliefs and ART Non-adherence Among HIV-Infected Current Drinkers in Mbarara, Uganda. AIDS Behav 21, 1812–1824 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1429-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-016-1429-3