Abstract

Introduction

This post-hoc analysis of the FRAME study investigated the long-term efficacy and safety of romosozumab followed by denosumab in postmenopausal Japanese women with osteoporosis at high fracture risk.

Materials and methods

Data from Japanese women with a high fracture risk participating in the international, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 FRAME study were analysed. High risk of fracture was defined as ≥ 1 fragility fracture with bone mineral density (BMD) ≤ − 2.5 standard deviations [SD], > 2 prevalent vertebral fractures, prevalent semiquantitative grade 3 vertebral fracture, or lumbar spine BMD < − 3.3 SD. Endpoints included incidence of new vertebral fracture at 12, 24 and 36 months and percentage change from baseline in BMD at the lumbar spine, total hip and femoral neck.

Results

187 Japanese subjects at high risk of fracture were enrolled in FRAME. Incidence of new vertebral fractures was lower with romosozumab/denosumab vs. placebo/denosumab at 12, 24 and 36 months (relative risk reduction at all timepoints: 84%; p = 0.056). BMD increases at 12, 24 and 36 months were greater in subjects receiving romosozumab/denosumab than placebo/denosumab (lumbar spine: 16.3%, 21.5% and 23.2% vs 0.4%, 8.1% and 10.4%; total hip: 4.9%, 7.9% and 8.9% vs 0.4%, 2.8% and 4.1%; femoral neck: 4.8%, 7.6% and 8.1% vs 0.3%, 3.3% and 3.7%, respectively; all p < 0.001 vs placebo/denosumab). Adverse events were generally balanced between groups.

Conclusion

Romosozumab/denosumab in Japanese subjects at high risk of fracture resulted in significant BMD gains and numerically lower vertebral fracture rate vs. placebo/denosumab at all timepoints measured.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Osteoporosis is a significant economic and societal burden which is predicted to worsen over the next 20 years [1]. In Japan, approximately 10 million women and 3 million men meet the dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) criteria for osteoporosis [2], and this number is expected to increase as the population ages. Osteoporosis is a global problem, with estimates from the US predicting that the number of fractures is expected to increase by 68% from 2018 to 2040, with related costs estimated to increase from $57 billion to more than $95 billion [1].

Initial osteoporosis treatments commonly used in Japan include bisphosphonates, selective oestrogen receptor modulators, eldecalcitol, denosumab and teriparatide [3]. Evidence suggests that fracture risk is highest in the first year following an initial fracture [4]; thus, a more potent initial treatment must be used in those at high risk of fracture [5]. Clinical trial evidence from the FRActure study in postmenopausal woMen with ostEoporosis (FRAME; NCT01575834) suggests that 12 months of treatment with the bone-forming agent romosozumab as the initial therapy leads to substantial increases in bone mineral density (BMD) that are maintained when subjects are switched to denosumab [6,7,8]. These significant improvements in BMD with romosozumab compared with placebo were associated with a rapid decrease in fracture risk [6]. After 12 months of romosozumab or placebo, subjects were switched to denosumab for an additional 12 months, during which BMD continued to improve and fracture risk continued to decrease [6]. The FRAME study was then extended for an additional 12 months to assess whether the increases in BMD and reductions in fracture risk were maintained longer term in women continuing denosumab for a total study duration of 36 months [7]. This extension study showed that women receiving 12 months of romosozumab followed by 24 months of denosumab had persistent reductions in fracture risk and continued BMD gains compared with placebo followed by denosumab [7]. A subgroup analysis of all Japanese women enrolled in FRAME reported that the efficacy and safety of romosozumab followed by denosumab over 36 months was consistent with that observed in the total population [8].

In Japan, romosozumab is indicated for the treatment of individuals with osteoporosis at high risk of fracture, defined using established single risk factors [9, 10]. This publication summarises the results of a post-hoc analysis of the FRAME study that investigated the long-term efficacy and safety of romosozumab followed by denosumab in Japanese women at high risk of fracture.

Materials and methods

Study design

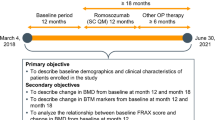

This is a post-hoc analysis of a subgroup of Japanese postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at high risk of fracture who participated in the international, randomised, double-blind, placebo controlled, phase 3 FRAME study [6, 7].

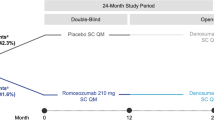

The study design of FRAME has been reported previously [6]. Briefly, 7180 subjects were randomised to receive either romosozumab 210 mg or placebo once monthly (QM) for 12 months of double-blind therapy. Randomisation was stratified by age (age ≥ 75 vs < 75 years) and prevalent vertebral fracture (yes vs no). At 12 months, all subjects continuing the study transitioned to open-label therapy with subcutaneous denosumab 60 mg every 6 months (Q6M) for 12 months; subjects completing 12 months of denosumab were then eligible for a further 12 months of denosumab treatment. The initial treatment assignment to romosozumab or placebo remained blinded throughout the entire study period. All subjects received daily calcium 500–1000 mg and vitamin D 600–800 IU. Those subjects who had a baseline serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) level of 20–40 ng/mL could initially receive a loading dose of vitamin D of 50,000–60,000 IU.

FRAME population

Subjects enrolled in FRAME were postmenopausal women aged 55–90 years with osteoporosis (defined as a BMD T-score at total hip or femoral neck of − 3.5 to − 2.5). Subjects had to have ≥ 2 vertebrae in the L1 through L4 region and ≥ 1 hip evaluable by DXA. Women with a history of hip fracture, severe vertebral fracture or ≥ 2 moderate vertebral fractures were excluded from the study. Other exclusion criteria included: recent or repeated use of strontium ranelate, fluoride, bisphosphonates, denosumab, any cathepsin K inhibitor, teriparatide, any parathyroid hormone analogue, oestrogen, hormonal ablation therapy, tibolone, cinacalcet, or calcitonin; recent prolonged use of systemic glucocorticoids; a history of metabolic bone disease or conditions affecting bone metabolism; osteonecrosis of the jaw; a serum 25(OH)D level of < 20 ng/mL; or current hypercalcaemia or hypocalcaemia.

The FRAME trial was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki–Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects, and the study protocol was approved by the ethics committee or institutional review board at each study centre. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants prior to study enrolment.

Assessments

Subjects underwent the following assessments: DXA scans of the lumbar spine and proximal femur at screening and 12, 24 and 36 months; lateral thoracic and lumbar spine radiographs at screening and 12, 24 and 36 months and at any other time in case of suspected vertebral fracture. A blinded central imaging vendor (BioClinica, Newark, CA, USA) assessed and graded vertebral radiographs using the Genant semiquantitative criteria [11] and confirmed nonvertebral fractures through review of radiographs or imaging reports. Only confirmed and adjudicated fractures by the central imaging assessor were included in the analysis.

Statistical analysis

The population for this analysis was Japanese postmenopausal women with osteoporosis at high risk of fracture, defined as those with ≥ 1 of the following: World Health Organisation severe/established osteoporosis criteria of BMD T-score ≤ − 2.5 at any skeletal site plus a history of ≥ 1 fragility fracture at baseline [12, 13]; ≥ 2 prevalent vertebral fractures [14, 15]; a severe semiquantitative grade at baseline (Grade 3) [11, 14]; or lumbar spine BMD T-score at baseline < − 3.3 [15, 16]. This definition of high risk of fracture is reflected in the current romosozumab label in Japan [10].

This analysis was conducted as per a previously published analysis of the Japanese subgroup in FRAME [8]. Efficacy analyses were conducted in the full analysis set for the Japanese postmenopausal high-risk subset, defined as subjects enrolled at study centres in Japan who were randomised to treatment with romosozumab/denosumab or placebo/denosumab and met the criteria for high risk as outlined above. The efficacy endpoints analysed were: the incidence of new vertebral fracture at 12, 24 and 36 months, and other fracture types at 36 months; and the percentage change from baseline in BMD at the lumbar spine, total hip and femoral neck at 12, 24 and 36 months. No multiplicity adjustment was applied in the endpoint analysis, and all p values were nominal. This subgroup analysis was not adequately powered to demonstrate statistical significance.

Determination of the least-squares mean percentage change from baseline in BMD was performed using analysis of covariance models with adjustment for treatment, age (< 75 vs ≥ 75 years), prevalent vertebral fracture (yes vs no) at baseline, baseline BMD, machine type and the interaction between baseline BMD and machine type. A responder analysis was performed to assess the percentage of subjects with any BMD change from baseline, as well as particular magnitudes of BMD change (≥ 3%, ≥ 6% and ≥ 10% from baseline) at the lumbar spine and total hip at 12 months. This analysis used logistic regression models adjusted for treatment, age and prevalent vertebral fracture stratification variables, and baseline value, machine type and baseline value-by-machine type interaction. Shifts in BMD T-score at the lumbar spine and total hip from ≤ − 2.5 at baseline to > − 2.5 at 12, 24 and 36 months were analysed using logistic regression models adjusting for treatment, age, prevalent vertebral fracture stratification variables and baseline BMD T-score.

Risk ratios for new vertebral fractures were calculated by the Mantel–Haenszel method, and p values were determined by logistic regression models that were stratified by age (< 75 vs ≥ 75 years) and prevalent vertebral fracture (yes vs no) at baseline. For other fracture types, hazard ratios and p values were determined by Cox proportional-hazards models stratified by age and prevalent vertebral fracture.

Nonvertebral fractures excluded fractures of the skull, facial bones, metacarpals, fingers and toes; pathologic fractures; and fractures associated with major trauma. Major nonvertebral fractures included fractures of the pelvis, distal femur, proximal tibia, ribs, proximal humerus, forearm and hip. Major osteoporotic fractures included clinical vertebral, hip, forearm and humerus fractures, but excluded pathological fractures.

Results

Subject disposition

Data from a total of 187 Japanese subjects who met the criteria for high risk were extracted for this analysis; 91 in the romosozumab/denosumab group and 96 in the placebo/denosumab group (Fig. 1). Of these, 69 subjects in the romosozumab/denosumab group and 84 in the placebo/denosumab group completed 36 months of the study. The most common reason for discontinuation was withdrawal of consent (10.2%), followed by adverse events (AEs; 6.4%). Seven subjects in the romosozumab/denosumab and five subjects in the placebo/denosumab group discontinued the study due to AEs, and one patient in each group was lost to follow-up. There were no deaths in the high-risk group.

Baseline characteristics

The mean age of the population was 71.6 years. More subjects in the romosozumab/denosumab group than the placebo/denosumab group were aged ≥ 75 years (42.9% vs 27.1%; Table 1). More subjects in the romosozumab/denosumab group than the placebo/denosumab group had ≥ 1 prevalent vertebral fracture (48.4% vs 31.3%), and more of these fractures were moderate in severity (34.1% vs 17.7%; Table 1). Other characteristics were generally similar between groups.

Bone mineral density

BMD at baseline according to machine type for all sites measured is summarised in Supplementary Table S1. For the lumbar spine, total hip and femoral neck, BMD increases after 12 months were significantly greater in subjects receiving romosozumab vs. placebo (Fig. 2a–c; p < 0.001 vs placebo for all). The significant difference in BMD between romosozumab and placebo recipients at 12 months was maintained at both 24 and 36 months (12 and 24 months, respectively, after the switch to denosumab in both groups).

Least-squares mean percentage change from baseline in bone mineral density resulting from romosozumab treatment for 12 months followed by denosumab treatment for 24 months in the a lumbar spine, b total hip and c femoral neck. BMD bone mineral density, Q6M every 6 months, QM once monthly. *Nominal p < 0.001 between treatment groups based on analysis of covariance model adjusting for treatment, age, prevalent vertebral fracture stratification variables, baseline value, machine type and baseline value-by-machine type interaction. Shaded area denotes the double-blind period, where subjects received romosozumab or placebo

The responder analysis showed that 12 months of treatment with romosozumab resulted in 97.6%, 95.2% and 83.1% of subjects achieving a ≥ 3%, ≥ 6% and ≥ 10% improvement from baseline, respectively, in lumbar spine BMD (Fig. 3a). Corresponding proportions of subjects receiving placebo were 18.3%, 3.2% and < 0.1%. A change from baseline of ≥ 3%, ≥ 6% and ≥ 10% in total hip BMD at 12 months was seen in 65.5%, 36.8% and 10.3%, respectively, of romosozumab recipients, and 14.7%, 6.3% and 1.1% of placebo recipients (Fig. 3b). All of the response rates in the romosozumab group were significantly greater than the response rates in the placebo group (p ≤ 0.016). These BMD gains resulted in 79.6% of the romosozumab/denosumab group achieving a lumbar spine BMD T-score > − 2.5 at 36 months, compared with 21.6% in the placebo/denosumab group (p < 0.001 vs placebo). The proportions of subjects achieving a total hip BMD T-score of > − 2.5 at 36 months were 57.1% and 36.7% in the romosozumab/denosumab and placebo/denosumab groups, respectively (p < 0.001 vs placebo).

Responder analysis of percentage change from baseline to 12 months in bone mineral density in a lumbar spine and b total hip for individual subjects. The x-axis represents each individual subject. Horizontal lines reflect 3%, 6% and 10% responses relative to baseline. N is the number of subjects with a baseline and ≥ 1 postbaseline assessment at or before 12 months

Fracture risk

The incidence of new vertebral fractures was numerically lower with romosozumab/denosumab vs. placebo/denosumab at 12, 24 and 36 months (relative risk reduction 84% at all timepoints; p = 0.056; Fig. 4). The risk of new fractures over 36 months decreased by 34%–65% for clinical, nonvertebral, major nonvertebral and major osteoporotic fractures, but these reductions were nonsignificant. Generally, the rate of these types of fractures was low in both groups and the study was not adequately powered to detect a difference in the rates of these fractures.

Fracture risk after romosozumab treatment for 12 months followed by denosumab treatment for 24 months. Subject incidence and relative risk reduction, based on relative risks, for new vertebral fracture by study visit in the analysis set for vertebral fractures. The last observation was carried forward for missing data. n number of subjects with fracture, N number of subjects analysed, Q6M every 6 months, QM once monthly, RRR relative risk reduction. Shaded area denotes the double-blind period, where subjects received romosozumab or placebo

Safety

All 187 Japanese subjects with a high risk of fracture were included in the safety analysis. Treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were experienced by 88.9% and 87.5% of subjects in the romosozumab/denosumab and placebo/denosumab groups, respectively (Table 2). A total of 4.4% and 5.2% of subjects in the romosozumab/denosumab and placebo/denosumab groups discontinued treatment because of AEs. The most frequent AEs in the romosozumab/denosumab and placebo/denosumab groups were nasopharyngitis (46.7% vs 43.8%), contusion (18.9% vs 7.3%), falls (16.7% vs 14.6%) and constipation (13.3% vs 9.4%; Table 2). Serious AEs (SAEs) occurred in 17.8% of subjects in the romosozumab/denosumab group and 15.6% in the placebo/denosumab group. There were no fatal AEs and no positively-adjudicated cardiovascular SAEs reported.

Events of interest that occurred during the study in high-risk subjects in the romosozumab/denosumab and placebo/denosumab groups were hypersensitivity (21.1% vs 18.8%), osteoarthritis (16.7% vs 19.8%), hyperostosis (4.4% vs 2.1%), malignancy (3.3% vs 1.0%) and injection-site reaction (2.2% vs 2.1%). There were no reports of osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ), atypical femoral fracture or hypocalcaemia (Table 2).

SAEs reported included hypersensitivity and hyperostosis in one patient each from the romosozumab/denosumab group, and osteoarthritis in two subjects receiving romosozumab/denosumab. All four cases of malignancy reported (one case each of colon cancer with liver metastases, gastric cancer and neoplasm of the appendix in the romosozumab/denosumab group, and one case of gastric adenocarcinoma in the placebo/denosumab group; Table 2) were considered SAEs.

During the overall study period, binding antibodies developed in 17.8% of high-risk subjects. No subjects developed neutralising antibodies. The presence of antibodies did not appear to affect the efficacy or safety of study treatments.

Discussion

This post-hoc analysis of a subgroup of Japanese subjects at high risk of fracture from the FRAME study indicates that subjects who receive 12 months of treatment with romosozumab followed by denosumab for 24 months have significant and sustained BMD improvements vs. placebo/denosumab. High-risk subjects who received romosozumab had higher rates of response at 12 months than subjects who received placebo, with almost all subjects (> 97%) in the romosozumab group achieving a clinically meaningful BMD gain in the lumbar spine of ≥ 3%; > 80% of subjects achieved a BMD gain of ≥ 10%. The exploratory analysis of fracture risk, while underpowered, suggested a trend towards reductions in fracture risk in patients receiving romosozumab/denosumab vs. placebo/denosumab, and the trend was consistent across all fracture types. These results are noteworthy considering the romosozumab/denosumab group had a higher proportion of individuals aged ≥ 75 years, a greater prevalence of baseline fractures and a higher FRAX at baseline than the placebo/denosumab group, and thus were at greater risk of fracture than the placebo/denosumab group.

These results are similar to those reported for the primary FRAME population and the Japanese FRAME subgroup analysis [7, 8]. The Japanese subgroup analysis supported the efficacy of romosozumab/denosumab seen in the global study and showed that this regimen is effective in Japanese patients [8], but it is also important to investigate the efficacy of romosozumab in Japanese subjects at high risk of fracture. The high-risk subgroup in the present analysis had an estimated 10-year FRAX probability of major osteoporotic fractures of 24.8% and 26.2% for the placebo/denosumab and romosozumab/denosumab groups, respectively. Individuals with FRAX probabilities such as these are also considered at high risk of fracture. A FRAX 10-year probability of ≥ 15% for a major osteoporotic fracture with low bone mass is indicated as one of the intervention thresholds in the Japanese guidelines for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis [17]. Kanis and colleagues estimated that, in 2011, there were 9.3 million women aged ≥ 50 years in Japan with a 10-year fracture probability of ≥ 15%. This number is set to increase to 12.7 million by 2035 [18]. Therefore, more potent initial therapy should be considered in subjects with a high risk of fracture, and data on the efficacy of potent regimens in these patients is of interest.

Only a small number of Japanese subjects enrolled in FRAME satisfied the criteria for high risk of fracture, which meant the analysis was underpowered for detection of statistically significant differences, particularly in fracture risk. However, the trends in fracture risk favoured romosozumab/denosumab, and the BMD gains seen suggest that treatment with romosozumab followed by denosumab can result in an improvement in BMD such that many high-risk subjects no longer meet the densitometric criteria for osteoporosis [5].

The AEs seen in high-risk Japanese subjects were similar to those seen in the overall FRAME population and the Japanese subgroup analysis [7, 8]. While there were two deaths due to cardiovascular causes and one case of ONJ in the Japanese subgroup [8], there were no deaths, positively-adjudicated cardiovascular SAEs or ONJ cases reported in the current high-risk Japanese subgroup.

The main limitation of this analysis was the small sample size of the high-risk subgroup, which meant the analysis lacked the statistical power to determine between-group differences. In addition, the baseline characteristics of the two treatment groups were not balanced, resulting in a more favourable risk profile in the placebo/denosumab group; however, this supports the conclusions. Future studies with a larger number of subjects at high risk of fracture are needed to confirm the promising results found in the present study.

In conclusion This subgroup analysis of the FRAME study showed that treatment with romosozumab followed by denosumab in Japanese subjects at high risk of fracture results in significant BMD gains and a trend towards reductions in fracture risk compared with placebo followed by denosumab through 36 months of follow-up. These results are consistent with the results of the Japanese subgroup analysis and the overall FRAME study results, suggesting that the sequence of romosozumab then denosumab is a robust and reasonable regimen for Japanese patients with osteoporosis at high risk of fracture.

Data availability

Qualified researchers may request data from Amgen clinical studies. Complete details are available at the following: https://wwwext.amgen.com/science/clinical-trials/clinical-data-transparency-practices/.

References

Lewiecki EM, Ortendahl JD, Vanderpuye-Orgle J, Grauer A, Arellano J, Lemay J, Harmon AL, Broder MS, Singer AJ (2019) Healthcare policy changes in osteoporosis can improve outcomes and reduce costs in the United States. JBMR Plus 3:e10192

Yoshimura N, Nakamura K (2016) Epidemiology of locomotive organ disorders and symptoms: an estimation using the population-based cohorts in Japan. Clin Rev Bone Miner Metab 14:68–73

Fujiwara S, Miyauchi A, Hamaya E, Nicholls RJ, Weston A, Baidya S, Pinto L, Barron R, Takada J (2018) Treatment patterns in patients with osteoporosis at high risk of fracture in Japan: retrospective chart review. Arch Osteoporos 13:34

Giangregorio LM, Leslie WD, Manitoba Bone Density P (2010) Time since prior fracture is a risk modifier for 10-year osteoporotic fractures. J Bone Miner Res 25:1400–1405

Cummings SR, Cosman F, Lewiecki EM, Schousboe JT, Bauer DC et al (2017) Goal-directed treatment for osteoporosis: a progress report from the ASBMR-NOF working group on goal-directed treatment for osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 32:3–10

Cosman F, Crittenden DB, Adachi JD, Binkley N, Czerwinski E, Ferrari S, Hofbauer LC, Lau E, Lewiecki EM, Miyauchi A, Zerbini CA, Milmont CE, Chen L, Maddox J, Meisner PD, Libanati C, Grauer A (2016) Romosozumab treatment in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N Engl J Med 375:1532–1543

Lewiecki EM, Dinavahi RV, Lazaretti-Castro M, Ebeling PR, Adachi JD, Miyauchi A, Gielen E, Milmont CE, Libanati C, Grauer A (2019) One year of romosozumab followed by two years of denosumab maintains fracture risk reductions: results of the FRAME extension study. J Bone Miner Res 34:419–428

Miyauchi A, Dinavahi RV, Crittenden DB, Yang W, Maddox JC, Hamaya E, Nakamura Y, Libanati C, Grauer A, Shimauchi J (2019) Increased bone mineral density for 1 year of romosozumab, vs placebo, followed by 2 years of denosumab in the Japanese subgroup of the pivotal FRAME trial and extension. Arch Osteoporos 14:59

Soen S, Fukunaga M, Sugimoto T, Sone T, Fujiwara S, Endo N, Gorai I, Shiraki M, Hagino H, Hosoi T, Ohta H, Yoneda T, Tomomitsu T, Japanese Society for B, Mineral R, Japan Osteoporosis Society Joint Review Committee for the Revision of the Diagnostic Criteria for Primary O (2013) Diagnostic criteria for primary osteoporosis: year 2012 revision. J Bone Miner Metab 31:247–257

Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (2019) Evenity subcutaneous injection 105 mg. Prescribing information (in Japanese). https://www.pmda.go.jp/PmdaSearch/iyakuDetail/112922_3999449G1025_1_03#WARNINGS. Accessed 27 Mar 2020.

Genant HK, Wu CY, van Kuijk C, Nevitt MC (1993) Vertebral fracture assessment using a semiquantitative technique. J Bone Miner Res 8:1137–1148

World Health Organization (1994) Assessment of fracture risk and its application to screening for postmenopausal osteoporosis. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/39142. Accessed May 25, 2020.

World Health Organization (1998) Guidelines for preclinical evaluation and clinical trials in osteoporosis. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/42088. Accessed Mar 9, 2020.

Gallagher JC, Genant HK, Crans GG, Vargas SJ, Krege JH (2005) Teriparatide reduces the fracture risk associated with increasing number and severity of osteoporotic fractures. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:1583–1587

Marcus R, Wang O, Satterwhite J, Mitlak B (2003) The skeletal response to teriparatide is largely independent of age, initial bone mineral density, and prevalent vertebral fractures in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J Bone Miner Res 18:18–23

Shiraki M, Kuroda T, Miyakawa N, Fujinawa N, Tanzawa K et al (2011) Design of a pragmatic approach to evaluate the effectiveness of concurrent treatment for the prevention of osteoporotic fractures: rationale, aims and organization of a Japanese Osteoporosis Intervention Trial (JOINT) initiated by the Research Group of Adequate Treatment of Osteoporosis (A-TOP). J Bone Miner Metab 29:37–43

Orimo H (2015) Japanese 2015 guidelines for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis (in Japanese). https://www.josteo.com/ja/guideline/doc/15_1.pdf. Accessed 27 Mar 2020.

Kanis JA, Johansson H, Oden A, McCloskey EV (2012) The distribution of FRAX®-based probabilities in women from Japan. J Bone Miner Metab 30:700–705

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sheridan Henness, PhD, who wrote the outline and first draft of this manuscript on behalf of Springer Healthcare Communications. This medical writing assistance was funded by Amgen K.K. and Astellas Pharma Inc.

Funding

Amgen Inc., Astellas, and UCB Pharma sponsored this study (NCT01575834).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AM enrolled patients. EH provided the concept for the study and contributed to subgroup analysis study design, interpretation, preparation of discussion and provision of references. WY, CL and CT were involved in conception and interpretation of the manuscript. KN contributed to the confirmation of the contents and interpretation of the safety results. JS performed the statistical analysis and provided interpretation. All authors read and approved drafts of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

A Miyauchi received consulting fees from Amgen, Astellas BioPharma K.K., and Teijin Pharma. E Hamaya, K Nishi and J Shimauchi are employees of Amgen K.K., Japan and E Hamaya reports holding stock in Amgen Inc. W Yang is an employee of Amgen Inc., USA. C Libanati is an employee of UCB Pharma, Belgium, and reports holding stock in UCB Pharma. C Tolman is an employee of Amgen and holds stock in Amgen.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

About this article

Cite this article

Miyauchi, A., Hamaya, E., Yang, W. et al. Romosozumab followed by denosumab in Japanese women with high fracture risk in the FRAME trial. J Bone Miner Metab 39, 278–288 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-020-01147-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-020-01147-5