Abstract

Endothelial dysfunction can be detected by the presence of elevated levels of biomarkers of endothelial cell activation. In this study, we aimed to establish whether correlations of these biomarkers with characteristics of patients with ankylosing spondylitis (AS) exist. We also studied the effect of anti-TNF-α therapy on these biomarkers. Serum sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 levels were measured by ELISA in 30 non-diabetic AS patients undergoing anti-TNF-α therapy, immediately before and after an infusion of infliximab. Correlations of these biomarkers with clinical features, systemic inflammation, metabolic syndrome and other serum and plasma biomarkers of cardiovascular risk were studied. Potential changes in the concentration of these biomarkers following an infliximab infusion were also assessed. sE-selectin showed a positive correlation with CRP (p = 0.02) and with other endothelial cell activation biomarkers such as sVCAM-1 (p = 0.019) and apelin (p = 0.008). sVCAM-1 negatively correlated with BMI (p = 0.018), diastolic blood pressure (p = 0.008) and serum glucose (p = 0.04). sVCAM-1 also showed a positive correlation with VAS spinal pain (p = 0.014) and apelin (p < 0.001). MCP-1 had a negative correlation with LDL cholesterol (p = 0.026) and ESR (p = 0.017). Patients with hip involvement and synovitis and/or enthesitis in other peripheral joints showed higher levels of MCP-1 (p = 0.004 and 0.02, respectively). A single infliximab infusion led to a significant reduction in sE-selectin (p = 0.0015) and sVCAM-1 (p = 0.04). Endothelial dysfunction correlates with inflammation and metabolic syndrome features in patients with AS. A beneficial effect of the anti-TNF-α blockade on endothelial dysfunction, manifested by a reduction in levels of biomarkers of endothelial cell activation, was observed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Chronic inflammatory diseases such as ankylosing spondylitis (AS) are closely associated with cardiovascular (CV) disease and metabolic syndrome (MeS). In this regard, not only do patients with AS have higher incidence of traditional CV risk factors, but also the presence of systemic inflammation in these patients boosts the development of accelerated atherosclerosis and increases CV mortality risk [1, 2].

It is well known that systemic inflammation leads to the release of pro-inflammatory factors that promote a series of pro-atherogenic functions in different tissues and organs, leading thus to insulin resistance, dyslipidemia and endothelial cell activation, among others [3].

Endothelial cell activation is one of the first steps in the progression of the atherosclerotic process. Inflammation and the presence of CV risk factors lead to an increased expression of leukocyte adhesion molecules, such as vascular endothelial adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and E-selectin, which favor the binding of monocytes and T lymphocytes to the inflamed endothelium [4]. After leukocyte adhesion, the monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) promotes the migration and penetration of inflammatory cells into the sub-endothelial space and synovium [5].

As a consequence of the involvement of VCAM-1, E-selectin and MCP-1 in the atherosclerotic process and inflammation, these molecules are considered as biomarkers of endothelial cell activation and atherosclerosis. Additionally, these molecules have been directly associated with CV disease [6, 7]. Elevated levels of soluble cell adhesion molecules such as VCAM-1 have been reported in the presence of endothelial dysfunction, atherosclerosis and chronic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [8–10].

Anti-TNF-α therapy is widely used for the treatment of AS patients, since it reduces inflammation, with the ensuing improvement in the disease [11, 12]. Additionally, several authors have reported that anti-TNF-α therapy improves endothelial function in these patients [13]. A beneficial effect of this drug has previously been demonstrated on some biomarkers of endothelial cell activation, inflammation, adipokines and metabolic syndrome (MeS)-related biomarkers in patients with AS [2, 14, 15].

To further investigate the biological mechanisms that may be associated with an improvement in endothelial function mediated by anti-TNF-α therapy, we assessed the effect of the chimeric anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody infliximab on three well-known endothelial cell activation biomarkers: E-selectin, MCP-1 and VCAM-1, in non-diabetic AS patients undergoing periodic treatment with this drug. We also aimed to establish whether correlations of these biomarkers with characteristics of patients with AS, including clinical features, laboratory parameters and other biomarkers, may exist.

Patients and methods

Patients

We assessed a consecutive series of 30 patients with AS attending hospital outpatient clinics seen over 14 months (January 2009–March 2010), who fulfilled the modified New York diagnostic criteria for AS [16]. They were treated by the same group of rheumatologists and were recruited from the Hospital Lucus Augusti (Xeral-Calde), Lugo, Spain.

AS patients on treatment with infliximab seen during the period of recruitment with diabetes mellitus or with plasma glucose levels greater than 110 mg/dL were excluded. None of the patients included in the study had hyperthyroidism or renal insufficiency. Also, patients seen during the recruitment period who had experienced CV events, including ischemic heart disease, heart failure, cerebrovascular accidents or peripheral arterial disease, were excluded. Patients were diagnosed as having hypertension if blood pressure was >140/90 mmHg or they were taking antihypertensive agents. Patients were considered to have dyslipidemia if they had hypercholesterolemia and/or hypertriglyceridemia (defined as diagnosis of hypercholesterolemia or hypertriglyceridemia by the patients’ family physicians, or total cholesterol and/or triglyceride levels in fasting plasma being >220 and >150 mg/dL, respectively). Obesity was defined if body mass index (BMI) (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in squared meters) was >30 [14, 15].

In all cases, the anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody infliximab was the first biologic therapy prescribed to these patients. This biologic therapy was started because of active disease. All patients included in the current study had begun treatment with non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) immediately after the disease diagnosis. All of them were still being treated with these drugs at the time of the study. At the time of this study, most patients were on treatment with naproxen: 500–1000 mg/day. Although the 2010 updated recommendations facilitate initiation of TNF-α blockers in AS and only ask for two NSAIDs with a minimum total treatment period of 4 weeks [17], for the initiation of anti-TNF-α therapy in these series of patients recruited between January 2009 to March 2010 they had to be treated with at least three NSAIDs prior to the onset of infliximab therapy. In addition, at the time of the study 23 of the 30 patients were in treatment with sulfasalazine (2–3 g/day) or they had previously been treated with this drug.

A clinical index of disease activity Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI range of 0–10) [18] was evaluated in all patients at the time of the study. Clinical information on hip involvement that was considered as an isolated feature, history of synovitis and/or enthesitis in other peripheral joints, history of anterior uveitis, presence of syndesmophytes and HLA-B27 status (typed by cell cytotoxicity) was assessed. Moreover, C-reactive protein (CRP), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), serum glucose, total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and triglycerides (fasting overnight determinations) were assessed in all the patients at the time of the study.

The characteristics of the AS patients included in this study have previously been described [15]. Briefly, 21 (70 %) were men, 6 (20 %) had hip involvement, and 11 (37 %) had synovitis and/or enthesitis in other peripheral joints. Also, 6 (20 %) had experienced anterior uveitis, 10 (33 %) had syndesmophytes on plain radiographs, and 20 (67 %) were HLA-B27 positive. The median disease duration at the time of the study (interquartile range—IQR) was 19 (12.5–27) years. The median (IQR) duration of periodical treatment with infliximab prior to the study date was 2 (1–3 years) years. Since at that time all patients were undergoing periodical treatment with the anti-TNF-α monoclonal antibody, infliximab, the mean BASDAI ± standard deviation (SD) was only 2.94 ± 2.11.

The local institutional committee approved anti-TNF-α therapy. Also, patients gave informed consent to participate in this study. This study was not supported by a pharmaceutical drug company.

Study protocol

In all cases, infliximab was given as an intravenous infusion in a saline solution over 120 min. All the basal determinations were made in the fasting state, prior to an infliximab infusion, and patients were kept in this state during the intravenous administration of the drug. Blood samples were taken at 0800 hour (time 0) for determination of the ESR (Westergren), CRP (latex immuno-turbidimetry), lipids (enzymatic colorimetry), plasma glucose and serum insulin (DPC, Dipesa, Los Angeles, CA, USA). As previously described, insulin resistance was estimated by the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) using the formula [insulin (µU/mL) × glucose (mmol/L)/22.57] [19]. Commercial ELISA kits were used to measure serum (s)E-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen, KHS2011, assay sensitivity = 0.033 ng/mL, intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were <5.4 and <6 %, [CA, USA]; Life Technologies, KHC1011; assay sensitivity = 5 pg/mL, intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were <4.9 and <7.5 % [CA, USA]; eBioscience, BMS232CE, assay sensitivity = 0.6 ng/mL, intra- and interassay coefficients of variation were <3.1 and <5.2 % [Vienna, Austria]). Total plasma adiponectin, osteoprotegerin (OPG), insulin-like growth factor 1(IGF-1) and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 (IGFBP-3) levels, serum resistin, leptin, visfatin, apelin, angiopoietin 2 (Angpt-2), asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), gelsolin, ghrelin, osteopontin (OPN), retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP-4) and tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) levels were determined by ELISA as previously described [15].

Subsequently, final blood sampling was performed for the determination of sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 levels immediately after the infliximab infusion (at time 120 min). No blood samples were taken at later times since the aim of the project was to evaluate the immediate effect of a single infliximab infusion on sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 levels, avoiding thus confounding factors (such as concomitant medications), which could alter the results if samples were taken after a more prolonged period of time. For the same reason, no control group was included in the study.

Statistical analysis

Variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (IQR). Correlation between basal sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 at time 0 with selected continuous variables was performed adjusting for age at the time of the study, sex and classic CV risk factors via estimation of the Pearson partial correlation coefficient (r).

The associations between baseline characteristics and E-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 serum concentrations were assessed by the Student’s paired t test. Differences in sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 levels between men and women and in patients with hypertension or not were assessed by Mann–Whitney U test.

Changes in sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 levels upon an infliximab infusion (just prior to—at time 0—and immediately after the end of infliximab infusion—at time 120 min) were compared using the paired Student t test.

Two-sided p values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. Analyses were performed using Stata 12/SE (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

Relationship of sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 levels with disease activity and clinical features

No difference was observed between circulating sE-selectin and MCP-1 and disease activity parameters, such as disease duration, BASDAI or VAS spinal pain at the time of the study (Table 1). However, a significant positive correlation was observed between sVCAM-1 and VAS spinal pain (r = 0.47; p = 0.014) (Table 1). When patients were stratified according to history of anterior uveitis, presence of syndesmophytes, hip involvement, synovitis and/or enthesitis in other peripheral joints and HLA-B27 status, we disclosed that patients with hip involvement or synovitis and/or enthesitis in other peripheral joints had significantly higher levels of sVCAM-1 (p = 0.004 and 0.02, respectively) (Table 2).

Relationship of demographic features, inflammation, adiposity and adipokines with circulating sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 levels

No significant association was observed between sE-selectin, MCP-1 or sVCAM-1 levels and age at the onset of symptoms (Table 1). However, a negative correlation between sVCAM-1 and BMI, as well as between MCP-1 and ESR at the time of disease diagnosis was observed (r = −0.45; p = 0.018 and r = −0.46; p = 0.017, respectively) (Table 1). Additionally, a positive correlation between sE-selectin and CRP at the time of the study was observed (r = 0.45; p = 0.02) (Table 1). When we assessed the potential association of these endothelial cell activation biomarkers with adipokines, a positive correlation of sE-selectin and sVCAM-1 with apelin levels was found (r = 0.50; p = 0.008 and r = 0.77; p < 0.001, respectively) (Table 3). No difference in sE-selectin, MCP-1 or sVCAM-1 serum levels between men and women was observed (Table 2).

Relationship of sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 levels with MeS features other than adiposity

sE-selectin did not show any statistical correlation with systolic or diastolic blood pressure, total cholesterol, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol, triglycerides, serum glucose levels, insulin sensitivity (QUICKI) or insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) (Tables 1, 3). However, an inverse correlation between sVCAM-1 and diastolic blood pressure and serum glucose was disclosed (r = −0.50; p = 0.008 and r = −0.40; p = 0.040, respectively), and also between MCP-1 and LDL cholesterol (r = −0.43; p = 0.026). Besides, a marginally significant correlation between MCP-1 and triglycerides was observed (r = 0.39; p = 0.044) (Table 1). No correlation was observed between the concentration of sE-selectin, MCP-1 or sVCAM-1 and MeS-associated biomarkers such as ghrelin or RBP-4 (Table 3). Likewise, when we stratified patients according to the presence or absence of arterial hypertension, no significant differences in the levels of the three biomarkers studied were shown (Table 2).

Relationship of sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 serum levels with other biomarkers of endothelial cell activation and inflammation

No association was observed between sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 serum levels and biomarkers of endothelial cell activation and inflammation such as ADMA, Angpt-2, OPN, OPG and gelsolin (Table 3). However, we found a positive correlation between sE-selectin and sVCAM-1 levels (r = 0.45; p = 0.019) (Table 3).

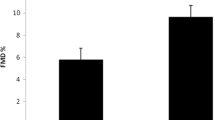

Changes in sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 levels upon infliximab administration

We disclosed that sE-selectin, MCP-1 and sVCAM-1 serum levels were reduced after a single anti-TNF-α infliximab infusion. In this regard, the mean ± SD values of sE-selectin were 48.09 ± 20.76 ng/mL immediately prior to infliximab infusion (time 0) and 40.77 ± 20.24 ng/mL at the end of the infusion (time 120 min) (p = 0.0015). Likewise, sVCAM-1 levels at time 0 were 650.96 ± 327.04 and 588.52 ± 209.38 ng/mL at time 120 min (p = 0.040). Regarding MCP-1, the mean concentration decreased from 192.71 ± 59.77 pg/mL at time 0 to 178.34 ± 50.28 pg/mL at time 120 min, even if it did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.074) (Fig. 1).

Discussion

In the present study, we provide evidence of the implication of endothelial cell activation molecules in the development of MeS in patients with AS, which could further influence the atherosclerotic process observed in these patients [20, 21]. We also observed an effect of TNF-α blockade manifested by a rapid reduction in the levels of biomarkers of endothelial cell activation following an infusion of infliximab. These changes may explain the beneficial effect observed by anti-TNF-α therapy on the mechanisms associated with accelerated atherosclerosis in patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases.

We also disclosed an association between sVCAM-1 and clinical features of the disease such as VAS spinal pain, hip involvement or synovitis and/or enthesitis in other peripheral joints. These results are in line with those reported by Azevedo et al. [22] in AS patients with active disease but not receiving anti-TNF-α therapy. According to these observations, it seems that sVCAM-1 may be a good marker of disease activity and severity.

Regarding sE-selectin, we observed a positive association between the levels of this protein and CRP. This finding is in accordance with the pro-inflammatory role proposed for the endothelial cell activation biomarkers. However, paradoxically, MCP-1 serum levels displayed an inverse correlation with ESR at the time of disease diagnosis. Similar results were obtained by Cid et al. [23] in giant cell arteritis patients when they stratified these patients according to the severity of the acute-phase response (taking into account parameters such as fever, weight loss, anemia and ESR values). Cid et al. [23] suggested that MCP-1 could be sequestered by its receptor, CCR2, which is known to be up-regulated in activated monocytes. The sequestration of circulating MCP-1 by its receptor could help to create a gradient of this molecule, facilitating thus the migration of monocytes and activated Th1 lymphocytes toward the sites of inflammation.

When we assessed the potential association between the endothelial cell activation molecules studied and other biomarkers of endothelial activation and inflammation, MeS-related biomarkers and adipokines, we also disclosed results that are in agreement with previously published data. In this regard, we found that apelin serum levels correlated positively with sVCAM-1 and sE-selectin. Interestingly, similar results were obtained in a study performed by Malyszko et al. [24] in chronic kidney disease patients. Even if these results may seem paradoxical, since apelin is supposed to be an anti-atherogenic and anti-inflammatory adipokine, this could be part of a compensatory mechanism to reduce CV risk in these patients. In this regard, in vitro studies have shown that apelin-13 induces the expression of VCAM-1 [25]. In line with these results, we also disclosed a positive association between sVCAM-1 and sE-selectin serum levels, which is in agreement with the pro-inflammatory function reported for these molecules.

Previous reports described that sVCAM-1 is significantly associated with BMI [22, 26]. Unexpectedly, in our study we disclosed an inverse association between sVCAM-1 and BMI. With respect to this, it is known that a pro-inflammatory status is related to obesity. However, only three of the 30 AS patients included in this study had BMI >30 kg/m2. On the other hand, it is important to keep in mind that in our study we assessed patients chronically treated with infliximab, who had low disease activity and very low inflammatory burden at the time of assessment. In addition, it has been previously observed that chronically infliximab-treated individuals with RA experience clinical improvement and increase in weight that may be due in part to a reduction in inflammation [27].

It has previously been reported that anti-TNF-α infliximab treatment may lead to an increase in cholesterol in patients with rheumatic diseases [28, 29]. Therefore, we believe that the inverse association between MCP-1 and LDL cholesterol shown in this study could be due to the qualitative and quantitative changes in the lipids mediated by the prolonged use of biologic therapy in our cohort of AS patients. On the other hand, we also disclosed a positive correlation between MCP-1 serum levels and triglycerides, which is in line with the results obtained by Simeoni et al. [30] in patients who underwent coronary angiography because of a history of chest pain or the presence of noninvasive tests consistent with myocardial ischemia.

Unexpectedly, in our study we observed that sVCAM-1 serum levels were inversely correlated with serum glucose and diastolic blood pressure, both features of MeS. Again, a possible explanation for our results may be that patients enrolled in our study had been chronically treated with infliximab, showing low disease activity and low inflammatory burden at the time of assessment. On the other hand, an improvement in MeS features including insulin sensitivity following an infliximab infusion was already described in AS patients treated with anti-TNF-α [19]. Therefore, as observed in that series, it is possible that prolonged infliximab therapy associated with a marked reduction in the inflammatory burden may negatively modify the expected correlation between the biomarkers of endothelial cell activation and MeS. In this regard, previous studies on this issue have yielded in some cases contradictory results, since some of them described a positive association with MeS features [31], while others did not observe any association between these parameters [32]. Therefore, further studies are needed to elucidate this issue, in particular in chronically treated patients with inflammatory arthritis that at the time of assessment have low disease activity and very low inflammatory response.

Finally, we assessed the immediate effect of an infusion of the anti-TNF-α antagonist infliximab on biomarkers of endothelial cell activation. Infliximab administration led to a statistically significant reduction in sE-selectin and sVCAM-1. Similar results were previously obtained in a series of RA patients with active disease who had been treated with anti-TNF-α therapy for more than 14 weeks. In that study, it was disclosed that anti-TNF-α infusion led to a decrease in serum sE-selectin and sVCAM-1 levels, even if they did not achieve statistical significance [33]. Although some authors also reported a significant reduction in VCAM-1 expression [34] or E-selectin [35] after anti-TNF-α treatment, others did not find any difference in the concentration of these molecules following TNF-α blockade [36, 37]. These apparently contradictory results may be due to the period of time elapsed between the assessment of these biomarkers and the time of anti-TNF-α administration.

Regarding MCP-1, Klimiuk et al. [38] reported a reduction in MCP-1 levels after infliximab infusion, mainly at week 2. Similar results were obtained by Eriksson et al. [39]. In the present study, we observed a rapid but not statistically significant short-time decrease in MCP-1 levels after a single infliximab infusion. Taking into account previous studies [38], it is possible that the assessment of MCP-1 levels in our patients later, that is to say several hours after infliximab administration, could have yielded significant differences when compared to baseline levels of this biomarker.

In a former study of our group, we assessed the effect of a single infusion of infliximab on endothelial function measured by flow-mediated vasodilatation in patients with RA refractory to conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs [40]. They had been treated with infliximab for at least 1 year and were currently being treated with this drug every 8 weeks. Following infusion of the drug, a dramatic and rapid increase in the percentage of endothelial-dependent vasodilatation was found. Percentages of endothelial-dependent vasodilatation at day 2 after infusion were greater than those observed 2 days before infusion. At day 7 post-infusion, the percentage of endothelial-dependent vasodilatation in all these patients was greater than before infusion at day 2. However, values returned to baseline by 4 weeks after infusion of the drug [40]. Therefore, this study showed that the effect of a single infusion of infliximab on endothelial function was transient [40]. In keeping with the former study, all the AS patients included in the present study were receiving infliximab therapy prior to the assessment and a rapid effect on biomarkers of endothelial cell activation was found. However, we did not assess the effect of the infusion later (e.g., after 14 days post-infusion). This constitutes a potential limitation of our study as we could not establish how sustainable were the effects of a single infusion of infliximab on biomarkers of endothelial cell activation. Nevertheless, considering the results shown in the former study [40], we may assume that the effect on biomarkers of endothelial function is probably transient.

In conclusion, despite potential limitations due to the small patient cohort and the low disease activity after long-term TNF-α blocker therapy, our results indicate that endothelial dysfunction correlates with inflammation and metabolic syndrome features in non-diabetic patients with AS undergoing anti-TNF-α therapy. A beneficial effect of the anti-TNF-α blockade on endothelial dysfunction, manifested by a reduction in levels of biomarkers of endothelial cell activation, was observed. These results may have biological implications due to the role of these biomarkers in the mechanisms associated with endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis in patients with chronic inflammatory arthritis.

References

Capkin E, Kiris A, Karkucak M, Durmus I, Gokmen F, Cansu A, Tosun M, Ayar A (2011) Investigation of effects of different treatment modalities on structural and functional vessel wall properties in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Joint Bone Spine 78:378–382

Genre F, López-Mejías R, Miranda-Filloy JA, Ubilla B, Carnero-López B, Blanco R, Pina T, González-Juanatey C, Llorca J, González-Gay MA (2014) Adipokines, biomarkers of endothelial activation, and metabolic syndrome in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Biomed Res Int 2014:860651

Libby P (2008) Role of inflammation in atherosclerosis associated with rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Med 121:S21–S31

Ulbrich H, Eriksson EE, Lindbom L (2003) Leukocyte and endothelial cell adhesion molecules as targets for therapeutic interventions in inflammatory disease. Trends Pharmacol Sci 24:640–647

Deshmane SL, Kremlev S, Amini S, Sawaya BE (2009) Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1): an overview. J Interferon Cytokine Res 29:313–326

Hwang SJ, Ballantyne CM, Sharrett AR, Smith LC, Davis CE, Gotto AM Jr, Boerwinkle E (1997) Circulating adhesion molecules VCAM-1, ICAM-1, and E-selectin in carotid atherosclerosis and incident coronary heart disease cases: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. Circulation 96:4219–4225

Malik I, Danesh J, Whincup P, Bhatia V, Papacosta O, Walker M, Lennon L, Thomson A, Haskard D (2001) Soluble adhesion molecules and prediction of coronary heart disease: a prospective study and meta-analysis. Lancet 358:971–976

Dessein PH, Joffe BI, Singh S (2005) Biomarkers of endothelial dysfunction, cardiovascular risk factors and atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 7:R634–R643

De Caterina R, Basta G, Lazzerini G, Dell’Omo G, Petrucci R, Morale M, Carmassi F, Pedrinelli R (1997) Soluble vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 as a biohumoral correlate of atherosclerosis. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 17:2646–2654

Wållberg-Jonsson S, Cvetkovic JT, Sundqvist KG, Lefvert AK, Rantapää-Dahlqvist S (2002) Activation of the immune system and inflammatory activity in relation to markers of atherothrombotic disease and atherosclerosis in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 29:875–882

Heldmann F, Brandt J, van der Horst-Bruinsma IE, Landewe R, Sieper J, Burmester GR, van den Bosch F, de Vlam K, Geusens P, Gaston H, Schewe S, Appelboom T, Emery P, Dougados M, Leirisalo-Repo M, Breban M, Listing J, Braun J (2011) The European ankylosing spondylitis infliximab cohort (EASIC): a European multicentre study of long term outcomes in patients with ankylosing spondylitis treated with infliximab. Clin Exp Rheumatol 29:672–680

Smolen JS, Emery P (2011) Infliximab: 12 years of experience. Arthritis Res Ther 13(1):S2. doi:10.1186/1478-6354-13-S1-S2

Syngle A, Vohra K, Sharma A, Kaur L (2010) Endothelial dysfunction in ankylosing spondylitis improves after tumor necrosis factor-α blockade. Clin Rheumatol 29:763–770

Genre F, López-Mejías R, Rueda-Gotor J, Miranda-Filloy JA, Ubilla B, Carnero-López B, Palmou-Fontana N, Gómez-Acebo I, Blanco R, Pina T, Ochoa R, González-Juanatey C, Llorca J, González-Gay MA (2014) Patients with ankylosing spondylitis and low disease activity because of anti-TNF-alpha therapy have higher TRAIL levels than controls: a potential compensatory effect. Mediat Inflamm 2014:798060

Genre F, López-Mejías R, Rueda-Gotor J, Miranda-Filloy JA, Ubilla B, Villar-Bonet A, Carnero-López B, Gómez-Acebo I, Blanco R, Pina T, González-Juanatey C, Llorca J, González-Gay MA (2014) IGF-1 and ADMA levels are inversely correlated in nondiabetic ankylosing spondylitis patients undergoing anti-TNF-alpha therapy. Biomed Res Int 2014:671061

van der Linden S, Valkenburg HA, Cats A (1984) Evaluation of diagnostic criteria for ankylosing spondylitis. A proposal for modification of the New York criteria. Arthritis Rheum 27:361–368

van der Heijde D, Sieper J, Maksymowych WP, Dougados M, Burgos-Vargas R, Landewé R, Rudwaleit M, Braun J, Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (2011) 2010 Update of the international ASAS recommendations for the use of anti-TNF agents in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 70:905–908

Garrett S, Jenkinson T, Kennedy LG, Whitelock H, Gaisford P, Calin A (1994) A new approach to defining disease status in ankylosing spondylitis: the Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index. J Rheumatol 21:2286–2291

Miranda-Filloy JA, Llorca J, Carnero-López B, González-Juanatey C, Blanco R, González-Gay MA (2012) TNF-α antagonist therapy improves insulin sensitivity in non-diabetic ankylosing spondylitis patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol 30:850–855

Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Vazquez-Rodriguez TR, Miranda-Filloy JA, Dierssen T, Vaqueiro I, Blanco R, Martin J, Llorca J, Gonzalez-Gay MA (2009) The high prevalence of subclinical atherosclerosis in patients with ankylosing spondylitis without clinically evident cardiovascular disease. Medicine (Baltimore) 88:358–365

Rueda-Gotor J, Corrales A, Blanco R, Fuentevilla P, Portilla V, Expósito R, Mata C, Pina T, González-Juanatey C, Llorca J, González-Gay M (2015) Atherosclerotic disease in axial spondyloarthritis: increased frequency of carotid plaques. Clin Exp Rheumatol 33:315–320

Azevedo VF, Faria-Neto JR, Stinghen A, Lorencetti PG, Miller WP, Gonçalves BP, Szyhta CC, Pecoits-Filho R (2013) IL-8 but not other biomarkers of endothelial damage is associated with disease activity in patients with ankylosing spondylitis without treatment with anti-TNF agents. Rheumatol Int 33:1779–1783

Cid MC, Hoffman MP, Hernández-Rodríguez J, Segarra M, Elkin M, Sánchez M, Vilardell C, García-Martínez A, Pla-Campo M, Grau JM, Kleinman HK (2006) Association between increased CCL2 (MCP-1) expression in lesions and persistence of disease activity in giant-cell arteritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 45:1356–1363

Malyszko J, Malyszko JS, Pawlak K, Mysliwiec M (2008) Visfatin and apelin, new adipocytokines, and their relation to endothelial function in patients with chronic renal failure. Adv Med Sci 53:32–36

Li X, Zhang X, Li F, Chen L, Li L, Qin X, Gao J, Su T, Zeng Y, Liao D (2010) 14-3-3 mediates apelin-13-induced enhancement of adhesion of monocytes to human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 42:403–409

Miller MA, Cappuccio FP (2006) Cellular adhesion molecules and their relationship with measures of obesity and metabolic syndrome in a multiethnic population. Int J Obes (Lond) 30:1176–1182

Gonzalez-Gay MA, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Miranda-Filloy JA, Martin J, Garcia-Unzueta MT, Llorca J (2011) Response to ‘Infliximab therapy increases body fat mass in early rheumatoid arthritis independently of changes in disease activity and levels of leptin and adiponectin: a randomized study over 21 months’. Arthritis Res Ther 13:404

Popa C, van den Hoogen FH, Radstake TR, Netea MG, Eijsbouts AE, den Heijer M, van der Meer JW, van Riel PL, Stalenhoef AF, Barrera P (2007) Modulation of lipoprotein plasma concentrations during long-term anti-TNF therapy in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 66:1503–1507

Choy E, Sattar N (2009) Interpreting lipid levels in the context of high-grade inflammatory states with a focus on rheumatoid arthritis: a challenge to conventional cardiovascular risk actions. Ann Rheum Dis 68:460–469. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.101964

Simeoni E, Hoffmann MM, Winkelmann BR, Ruiz J, Fleury S, Boehm BO, März W, Vassalli G (2004) Association between the A-2518G polymorphism in the monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 gene and insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 47:1574–1580

Kressel G, Trunz B, Bub A, Hülsmann O, Wolters M, Lichtinghagen R, Stichtenoth DO, Hahn A (2009) Systemic and vascular markers of inflammation in relation to metabolic syndrome and insulin resistance in adults with elevated atherosclerosis risk. Atherosclerosis 202:263–271

Couillard C, Ruel G, Archer WR, Pomerleau S, Bergeron J, Couture P, Lamarche B, Bergeron N (2005) Circulating levels of oxidative stress markers and endothelial adhesion molecules in men with abdominal obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:6454–6459

Gonzalez-Gay MA, Garcia-Unzueta MT, De Matias JM, Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Garcia-Porrua C, Sanchez-Andrade A, Martin J, Llorca J (2006) Influence of anti-TNF-alpha infliximab therapy on adhesion molecules associated with atherogenesis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 24:373–379

Baeten D, Kruithof E, Van den Bosch F, Demetter P, Van Damme N, Cuvelier C, De Vos M, Mielants H, Veys EM, De Keyser F (2001) Immunomodulatory effects of anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy on synovium in spondylarthropathy: histologic findings in eight patients from an open-label pilot study. Arthritis Rheum 44:186–195

Zanni MV, Stanley TL, Makimura H, Chen CY, Grinspoon SK (2010) Effects of TNF-alpha antagonism on E-selectin in obese subjects with metabolic dysregulation. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 73:48–54

Orüm H, Pamuk GE, Pamuk ON, Demir M, Turgut B (2012) Does anti-TNF therapy cause any change in platelet activation in ankylosing spondylitis patients? A comparative study. J Thromb Thrombolysis 33:154–159

Sari I, Alacacioglu A, Kebapcilar L, Taylan A, Bilgir O, Yildiz Y, Yuksel A, Kozaci DL (2010) Assessment of soluble cell adhesion molecules and soluble CD40 ligand levels in ankylosing spondylitis. Joint Bone Spine 77:85–87

Klimiuk PA, Sierakowski S, Domyslawska I, Chwiecko J (2006) Regulation of serum chemokines following infliximab therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol 24:529–533

Eriksson C, Rantapää-Dahlqvist S, Sundqvist KG (2013) Changes in chemokines and their receptors in blood during treatment with the TNF inhibitor infliximab in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 42:260–265

Gonzalez-Juanatey C, Testa A, Garcia-Castelo A, Garcia-Porrua C, Llorca J, Gonzalez-Gay MA (2004) Active but transient improvement of endothelial function in rheumatoid arthritis patients undergoing long-term treatment with anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha antibody. Arthritis Rheum 51:447–450

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ms. Susana Escandon and Isabel Castro-Fernandez (nurses from the Rheumatology Outpatient Clinic), Ms. Pilar Ruiz (nurse from the Hematology Division) and the members of the Biochemistry Department from Hospital Lucus Augusti/Xeral-Calde (Lugo, Spain), as well as Ms. Patricia Fuentevilla Rodríguez and Virginia Portilla González (nurses from the Rheumatology Division, Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla) (Santander, Spain), for their valuable help to undertake this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study was supported by European Union Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (FEDER) funds and “Fondo de Investigación Sanitaria” (Grants PI06/0024, PS09/00748 and PI12/00060) (Spain). This work was also partially supported by Redes temáticas de investigación cooperativa en salud (RETICS) Programs, RD08/0075 (RIER) and RD12/0009/0013, from “Instituto de Salud Carlos III” (ISCIII) (Spain). F. G. and B. U. are supported by funds from the RETICS Program (RIER). R. L. M. is a recipient of a Sara Borrell postdoctoral fellowship from the Instituto de Salud Carlos III at the Spanish Ministry of Health (Spain).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Fernanda Genre and Raquel López-Mejías have equally contributed to this study.

Miguel A. Gonzalez-Gay and Javier Llorca shared senior authorship in this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Genre, F., López-Mejías, R., Miranda-Filloy, J.A. et al. Anti-TNF-α therapy reduces endothelial cell activation in non-diabetic ankylosing spondylitis patients. Rheumatol Int 35, 2069–2078 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-015-3314-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-015-3314-1