Abstract

Background and Purpose

This study aimed at comparing short-term clinical outcome after thrombectomy in patients directly admitted (DA) to a comprehensive stroke center with patients secondarily transferred (ST) from a primary stroke center.

Methods

In a prospective regional stroke registry, all stroke patients with a premorbid modified Rankin scale (mRS) score 0–2 who were admitted within 24 h after stroke onset and treated with thrombectomy between 2014 and 2017 were retrospectively analyzed. Patients with DA and ST were compared regarding the proportion of good outcome (discharge mRS 0–2), median discharge mRS, mRS shift (difference between premorbid mRS and mRS on discharge) and occurrence of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage.

Results

Out of 2797 patients, 1051 (37.6%) achieved good clinical outcome. In the DA group (n = 1657), proportion of good outcome was higher (DA 42.2% vs. ST 30.9%, P < 0.001) and median discharge mRS (DA 3 vs. ST 4, P < 0.001) and median mRS shift (DA 3 vs. ST 4, P < 0.001) were lower. The rate of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage was similar in both groups (DA 9.3% vs. ST 7.5%, P = 0.101). Multivariate analysis revealed that direct admission was an independent predictor of good clinical outcome (adjusted odds ratio, OR 1.32, confidence interval, CI 1.09–1.60, P = 0.004).

Conclusion

These results confirm prior studies stating that DA to a comprehensive stroke center leads to better outcome compared to ST in stroke patients undergoing thrombectomy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There is an ongoing debate concerning the prehospital pathway of stroke patients: should patients in remote areas with suspected stroke be admitted to the nearest primary stroke center first to receive intravenous thrombolysis (IVT), if eligible and then be secondarily transferred (ST) to a comprehensive stroke center (CSC) for endovascular thrombectomy (EVT) or should they be directly admitted (DA) to a CSC [1, 2]?

In Baden-Württemberg, a state in southwest Germany with an area of 35,751 km2 and 11 million inhabitants, the incidence of ischemic stroke was 254 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2014. Of these patients 2.4% underwent EVT at 14 centers. The rate of EVT throughout Germany was 2.3% in 2014. Approximately 140 stroke units are available in Baden-Württemberg, distributed by the Ministry of Social Affairs and therefore assuring a sufficient geographical coverage [3, 4]. Emergency physicians and paramedics are required by law to transfer patients with suspected stroke to the next primary stroke center regardless of the stroke severity. This regulation was introduced when IVT was the only treatment for acute ischemic stroke. Now that EVT has been shown to be more effective in proximal arterial occlusion, the abovementioned regulation carries the risk of delaying EVT in these patients. This retrospective study therefore aimed at analyzing the stroke registry of Baden-Württemberg regarding transfer times and clinical outcome in the DA and ST pathways.

Methods

Study Design

This was a retrospective observational cohort study based on a prospectively maintained regional stroke registry. All stroke centers in Baden-Württemberg are required to contribute data to a prospective registry without the need of informed consent. This study is therefore exempt from institutional review board approval. The stroke registry was designed in 2004 and has been maintained for quality assurance of IVT treatment; however, some parameters such as occlusion site, time of groin puncture and modified Rankin scale (mRS) score at 90 days after stroke onset are not documented.

Patient Selection

Registry data of patients treated between January 2014 and December 2017 were analyzed. Inclusion criteria were treatment with EVT, premorbid mRS 0–2 and admission to a CSC within 24 h after stroke onset. Patients with missing discharge mRS were excluded.

Outcome Measures

Primary outcome parameters were time from onset to admission at a CSC and good clinical outcome defined as a discharge mRS of 0–2. Secondary outcome parameters were discharge mRS score, mRS shift (difference between premorbid mRS and mRS on discharge), hospital mortality and occurrence of symptomatic intracranial hemorrhage (any intracranial hemorrhage associated with neurological deterioration).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R version 3.4.3 (R, Open Source). Comparisons between DA and ST were performed using Student’s t-test, Mann-Whitney U-test and χ2-test. All variables were entered into a univariate analysis to identify possible predictors of clinical outcome. Variables with P < 0.05 were then included in a multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify independent predictors of good clinical outcome. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

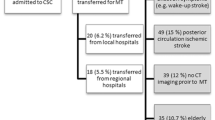

In total, 2797 patients were selected for analysis (Fig. 1), of which 59.2% were admitted directly to a CSC (DA group).

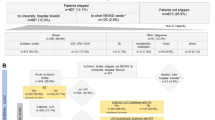

Patients in the DA group were admitted significantly earlier to a CSC (median 102 vs. 210 min, P < 0.001) compared to ST and received IVT more frequently (61.9% vs. 48.0%, P < 0.001). Out of 2797 patients, 1051 (37.6%) achieved a good outcome. In the DA group the proportion of good outcome was significantly higher (DA 42.2% vs. ST 30.9%, P < 0.001) and median discharge mRS (DA 3 vs. ST 4, P < 0.001) and median mRS shift (DA 3 vs. ST 4, P < 0.001) were significantly lower (Fig. 2). The rate of hospital mortality was significantly lower in the DA group (DA 17.7% vs. ST 24.3%, P < 0.001) and the proportion of intracranial hemorrhage was similar in both groups (DA 9.3% vs. ST 7.5%, P = 0.101) (Table 1).

Table 2 compares the characteristics of patients with good and poor outcome. When including all variables with P < 0.05 in a multivariate logistic analysis, direct admission to a CSC was an independent predictor of good clinical outcome (adjusted OR 1.32, CI 1.09–1.60, P = 0.004), independent of the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score. Bridging IVT was not a predictor of outcome (P = 0.382) (Table 3).

Discussion

This retrospective study analyzed a regional stroke registry and compared DA and ST regarding time metrics and short-term clinical outcome in 2797 patients. The data show that secondary transfer to a CSC takes more than twice as much time as direct admission, even in a small state like Baden-Württemberg. Similar results have been published by Park et al. and Prothmann et al. (Table 4; [5, 6]). Hence, interhospital transfer leads to a considerable delay of EVT in ST patients [7, 8]. Mokin et al. reported that one out of three patients becomes ineligible for thrombectomy because of unfavorable Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score (ASPECTS) worsening following interhospital transfer [9].

According to the present results, patients in the DA group have better clinical outcome and a lower rate of hospital mortality compared to ST patients. Direct admission was an independent predictor of good outcome. Hence, this study with 2797 patients confirms a recently published meta-analysis on DA vs. ST with 2068 patients [5, 6, 10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. This is an important finding, because in many German states including Baden-Württemberg emergency doctors and paramedics are required to transfer patients to the nearest hospitals certified for IVT. This regulation was issued when IVT was the only treatment option of ischemic stroke. Nowadays it is well known that IVT is unable to remove long thrombi [17], which led to the development and refinement of mechanical thrombectomy devices. Several randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that EVT with or without IVT is superior to IVT alone [18]; however, EVT requires more technical equipment and specialized staff compared to IVT and can only be provided in CSC.

These results have two important implications: first, emergency doctors and paramedics should be permitted and trained to identify those patients that are more likely to suffer from large vessel occlusion and therefore requiring direct transfer to a CSC for EVT. Simplified stroke severity scores can be helpful here, because large vessel occlusions are usually associated with a higher stroke severity [19]. Transcranial doppler ultrasound performed by emergency physicians is a potential option as well; however, it is accompanied by several obstacles, such as an insufficient temporal bone window in many patients and an extensive training, which is necessary for adequate Doppler ultrasound [20].

Second, interhospital transfer times need to be improved. There are several reasons for this time delay, such as inefficiencies in triaging and availability of patient transport [21, 22]. Further studies are necessary to determine where exactly time is unnecessarily lost but this can be different in every hospital. Admitting stroke patients with suspected large vessel occlusion directly to a CSC may put primary stroke centers under financial pressure; however, less than 3% of stroke patients in Germany underwent EVT in 2014 [3]. Therefore, this should not be a matter of concern. Besides, primary stroke centers are still important for a nationwide stroke unit coverage. Besides DA and ST, there is a novel triage concept in which neurointerventionalists are transferred to primary stroke centers for EVT [23,24,25,26]. Further trials including this triaging option should be considered as well when reforming triage pathways in a stroke network.

The major strength of this study is its size with 2797 patients. Although its size exceeds those of previous studies on DA and ST, it has several limitations. A significant weakness is the retrospective and nonrandomized nature of this study. It is a potential bias that patients admitted to a primary stroke center were only selected for transfer to a CSC when they were severely affected, and therefore a priori had a lower chance of good outcome, whereas patients that were less severely affected were nevertheless included in the MS pathway. This is reflected by the higher stroke severity at baseline in the DS group. Out of 4312 patients 1199 (27.8%) had to be excluded due to missing discharge mRS, mostly in patients who were transferred to another hospital after thrombectomy, which is a potential bias but the results are in accordance with previous studies [10]. Furthermore, parameters such as time from stroke onset to groin puncture, occlusion site and recanalization success were not available, which might also cause a bias. Moreover, discharge mRS but not 90-day mRS was available in this stroke registry. Nonetheless, early mRS has been reported to strongly correlate with 90-day mRS scores [27].

Conclusion

The results confirm previous studies and show that time from onset to admission at a CSC in ST patients is more than twice as much compared to DA patients and associated with worse outcome. Emergency physicians should be allowed to transport stroke patients to any institution they think is most appropriate and should not be restricted by any regulations.

Abbreviations

- CSC:

-

Comprehensive stroke center

- DA:

-

Direct admission

- EVT:

-

Endovascular thrombectomy

- IVT:

-

Intravenous thrombolysis

- ST:

-

Secondary transfer

References

Caplan LR. Primary stroke centers vs comprehensive stroke centers with Interventional capabilities: which is better for a patient with suspected stroke? JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:504–6.

Fiehler J. Mothership or drip and ship? Radiologe. 2019;59:610–5.

Krogias C, Bartig D, Kitzrow M, Brassel F, Busch EW, Nolden-Koch M, et al. Verfügbarkeit der mechanischen Thrombektomie bei akutem Hirninfarkt. Nervenarzt. 2017;88:1177–85.

Berlis A, Morhard D, Weber W. Flächendeckende Versorgung des akuten Schlaganfalls im Jahr 2016 und 2017 durch Neuro-Radiologen mittels mechanischer Thrombektomie in Deutschland anhand des DeGIR/DGNR-Registers. Röfo. 2019;191:613–7.

Park MS, Yoon W, Kim JT, Choi KH, Kang SH, Kim BC, et al. Drip, ship, and on-demand Endovascular therapy for acute Ischemic stroke. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e150668.

Prothmann S, Schwaiger BJ, Gersing AS, Reith W, Niederstadt T, Felber A, et al. Acute recanalization of thrombo-embolic Ischemic stroke with pREset (ARTEsp): the impact of occlusion time on clinical outcome of directly admitted and transferred patients. J Neurointerv Surg. 2017;9:817–22.

Bücke P, Pérez MA, Schmid E, Nolte CH, Bäzner H, Henkes H. Endovascular Thrombectomy in acute Ischemic stroke: outcome in referred versus directly admitted patients. Clin Neuroradiol. 2018;28:235–44.

Pfaff J, Pham M, Herweh C, Wolf M, Ringleb PA, Schönenberger S, et al. Clinical outcome after mechanical thrombectomy in non-elderly patients with acute Ischemic stroke in the anterior circulation: primary admission versus patients referred from remote hospitals. Clin Neuroradiol. 2017;27:185–92.

Mokin M, Gupta R, Guerrero WR, Rose DZ, Burgin WS, Sivakanthan S. ASPECTS decay during inter-facility transfer in patients with large vessel occlusion strokes. J Neurointerv Surg. 2017;9:442–4.

Ismail M, Armoiry X, Tau N, Zhu F, Sadeh-Gonik U, Piotin M, et al. Mothership versus drip and ship for thrombectomy in patients who had an acute stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019;11:14–9.

Saver JL, Goyal M, Bonafe A, Diener HC, Levy EI, Pereira VM, et al. Stent-Retriever Thrombectomy after Intravenous t‑PA vs. t‑PA Alone in Stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2285–95.

Weber R, Reimann G, Weimar C, Winkler A, Berger K, Nordmeyer H, et al. Outcome and periprocedural time management in referred versus directly admitted stroke patients treated with thrombectomy. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2016;9:79–84.

Rinaldo L, Brinjikji W, McCutcheon BA, Bydon M, Cloft H, Kallmes DF, et al. Hospital transfer associated with increased mortality after endovascular revascularization for acute ischemic stroke. J Neurointerv Surg. 2017;9:1166–72.

Gerschenfeld G, Muresan IP, Blanc R, Obadia M, Abrivard M, Piotin M, et al. Two paradigms for endovascular thrombectomy after intravenous thrombolysis for acute ischemic stroke. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:549–56.

Froehler MT, Saver JL, Zaidat OO, Jahan R, Aziz-Sultan MA, Klucznik RP, et al. Interhospital transfer before thrombectomy is associated with delayed treatment and worse outcome in the STRATIS registry (systematic evaluation of patients treated with neurothrombectomy devices for acute ischemic stroke). Circulation. 2017;136:2311–21.

Weisenburger-Lile D, Blanc R, Kyheng M, Desilles JP, Labreuche J, Piotin M, et al. Direct admission versus secondary transfer for acute stroke patients treated with intravenous thrombolysis and thrombectomy: insights from the endovascular treatment in ischemic stroke registry. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2019;47:112–20. https://doi.org/10.1159/000499112

Riedel CH, Zimmermann P, Jensen-Kondering U, Stingele R, Deuschl G, Jansen O. The importance of size successful recanalization by intravenous thrombolysis in acute anterior stroke depends on thrombus length. Stroke. 2011;42:1775–7.

Goyal M, Menon BK, van Zwam WH, Dippel DW, Mitchell PJ, Demchuk AM, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy after large-vessel ischaemic stroke: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from five randomised trials. Lancet. 2016;387:1723–31.

Purrucker JC, Härtig F, Richter H, Engelbrecht A, Hartmann J, Auer J, et al. Design and validation of a clinical scale for prehospital stroke recognition, severity grading and prediction of large vessel occlusion: the shortened NIH Stroke Scale for emergency medical services. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e16893.

Connolly F, Röhl JE, Guthke C, Wengert O, Valdueza JM, Schreiber SJ. Emergency room use of “fast-track” ultrasound in acute stroke: an observational study. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2019;45:1103–11.

Menon BK, Sajobi TT, Zhang Y, Rempel JL, Shuaib A, Thornton J, et al. Analysis of workflow and time to treatment on thrombectomy outcome in the ESCAPE randomized controlled trial. Circulation. 2016;133:2279–86.

Ng FC, Low E, Andrew E, Smith K, Campbell BCV, Hand PJ, et al. Deconstruction of Interhospital transfer workflow in large vessel occlusion. Stroke. 2017;48:1976–9.

Hui FK, El Mekabaty A, Schultz J, Hong K, Horton K, Urrutia V, et al. Helistroke: neurointerventionalist helicopter transport for interventional stroke treatment: proof of concept and rationale. J Neurointerv Surg. 2018;10:225–8.

Wei D, Oxley TJ, Nistal DA, Mascitelli JR, Wilson N, Stein L, et al. Mobile interventional stroke teams lead to faster treatment times for thrombectomy in large vessel occlusion. Stroke. 2017;48:3295–300.

Brekenfeld C, Goebell E, Schmidt H, Henningsen H, Kraemer C, Tebben J, et al. ‘Drip-and-drive’: shipping the neurointerventionalist to provide mechanical thrombectomy in primary stroke centers. J Neurointerv Surg. 2018;10:932–6.

Seker F, Möhlenbruch MA, Nagel S, Ulfert C, Schönenberger S, Pfaff J, et al. Clinical results of a new concept of neurothrombectomy coverage at a remote hospital—“drive the doctor”. Int J Stroke. 2018;13:696–9.

Ovbiagele B, Saver JL. Day-90 acute Ischemic stroke outcomes can be derived from early functional activity level. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29:50–6.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F. Seker, S. Bonekamp, M. Bendszus and M.A. Möhlenbruch conceived the study and initiated the study design. S. Hyrenbach and S. Rode contributed to acquisition of data. F. Seker, M. Bendszus and M.A. Möhlenbruch contributed to analysis and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to refinement of the study protocol and reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

F. Seker, S. Bonekamp, S. Rode, S. Hyrenbach, M. Bendszus and M.A. Möhlenbruch declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Seker, F., Bonekamp, S., Rode, S. et al. Direct Admission vs. Secondary Transfer to a Comprehensive Stroke Center for Thrombectomy. Clin Neuroradiol 30, 795–800 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00062-019-00842-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00062-019-00842-9