Abstract

This paper revisits intervention effects in Mandarin Chinese why-questions. I present new data showing that the ability for quantifiers to induce intervention hinges upon their monotonicity and their ability to be interpreted as topics. I then develop a semantic account that correlates topicality with monotone properties. Furthermore, I propose that why-questions in Chinese are idiosyncratic, in that the Chinese equivalent of why directly merges at a high scope position that stays above a propositional argument. Combining the semantic idiosyncrasies of why-questions with the theory of topicality, I conclude that a wide range of intervention phenomena can be accounted for in terms of interpretation failure.

This paper benefits from discussions with Jun Chen and Lihua Xu. I also thank one anonymous reviewer for the abstract of the TbiLLC 2015 conference and conference attendees for their feedback. I am particularly indebted to the two anonymous reviewers for the TbiLLC 2015 Post-Proceedings for their detailed and insightful comments and suggestions for improvement. All the remaining errors are my own.

Access provided by CONRICYT-eBooks. Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Data

This paper presents a semantic account of the quantifier-induced intervention effects in Chinese why-questions, schematized as follows.

That is, unacceptability arises when a quantifier c-commands the interrogative phrase why. Using Chinese data, this paper argues that the intervention induced by why-questions is distinct from other intervention effects that arise in non-why interrogative questions, which have received detailed investigations in the literature.Footnote 1 Specifically, I present new data showing that intervention effects in Chinese why-questions are sensitive to the type of quantifier. Since the Mandarin Chinese-speaking community is huge by population size and internal linguistic/social diversity, there is an important issue as to the extent of variation in how an exhaustive list of quantifiers is accepted. The previous literature has (understandably) tended to abstract away from any such variation. While I won’t be able to offer any characterization of the nature of variation here, to the degree possible I have tried to minimize variation by focusing on a specific dialect group: the Mandarin spoken in Beijing and the adjacent Dongbei ‘Northeast’ provinces. My primary consultants are three female speakers in their twenties. Two additional male speakers in their thirties are recruited for a subset of the elicited data. All of them come from the above two regions.

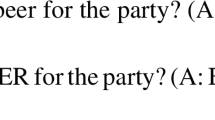

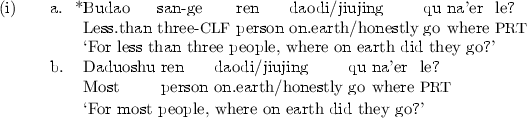

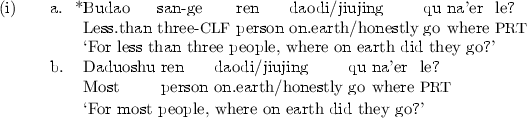

As (2) shows, when weishenme ‘why’ is c-commanded by a monotone decreasing quantificational DP, oddness ensues.Footnote 2

In contrast, a quantificational DP with a simplex monotone increasing determiner, such as most people, or a few people, does not induce intervention effects.Footnote 3

To make things more complex, one class of monotone increasing quantificational DPs with morphosyntactically complex determiners induce weak intervention. This class includes modified numerals such as at least three people, more than three people, etc. Non-monotonic bare numerals, such as three people, also induce weak intervention. An example is given in (4).

My notational choice here, using ?? in (4) to contrast with the use of # in (2), will be justified in my coming argument that the unacceptability found in examples in (2) results from interpretation failure, whereas the unacceptability in (4) is a case of contextual infelicity. The choice also reflects the intuition of my consulted speakers. When uttered out of the blue, (4) triggers rather low judgments for some speakers, while for other speakers the oddness is less severe than that which is induced in monotone decreasing contexts. So far, I have only discussed matrix why-questions. In an embedded why-question, morphosyntactically simplex monotone increasing quantifiers still induce no intervention, as shown by the perfectly acceptable sentence as follows:

More noteworthy is the fact that the weak intervention we witness in (4) disappears in embedded why-questions. This is demonstrated by the acceptability of (6).

By comparison, intervention cannot be circumvented in embedded contexts for monotone decreasing quantifiers. As (7) illustrates, the unacceptability in an embedded why-question is as strong as it is in a matrix one.

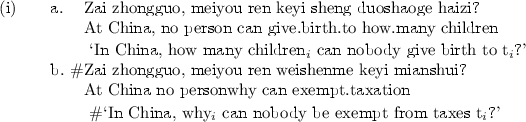

In sum, intervention effects in Chinese why-questions are sensitive to quantifier monotonicity. In addition, they are sensitive to whether why-questions occur in matrix or embedded contexts. The overall pattern is summarized in (8):

Apart from quantificational DPs, adverbs of quantification exhibit similar patterns. (9) illustrates the ban for monotone decreasing quantificational adverbs to c-command weishenme ‘why’.

Furthermore, this ban on c-commanding quantificational adverbs is lifted if the adverbs are monotone increasing or non-monotonic:

In this paper, I propose to account for this complex array of data in terms of the idiosyncratic semantics of weishenme ‘why’. In a nutshell, I argue that Chinese weishenme must be initially merged at the high scope position of [Spec, CP]. When quantifiers are interpreted as taking wide scope over [Spec, CP], we obtain coherent interpretations. On the other hand, intervention arises when certain quantifiers are unable to be interpreted at such high scope. Hence, this account of intervention effects in why-questions does not involve ‘real’ intervention, in the sense that no mechanism of covert movement is assumed. Rather, my central claim in this paper is that the unacceptability we are dealing with here is not syntactic ill-formedness, but interpretational failure, i.e., a native speaker cannot assign an interpretation to a why-question in certain scopal relations.Footnote 4

The rest of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews previous syntactic theories of the Chinese intervention effects in why-questions. Section 3 develops a semantic account with reference to why’s syntactic and semantic idiosyncrasies. Afterwards, I provide evidence that the intervention patterns of quantifiers correlate with quantifier monotonicity. Section 4 concludes the paper.

2 Past Accounts of the Quantifier-Induced Intervention Effects

In this section, I review several recent approaches to the Chinese intervention effects in why-questions that resort to covert LF movement. I then show that this line of research holds out little promise in accommodating the full range of data as discussed in the previous section. In the next section, I develop a semantic account that achieves the desired empirical coverage.

Building upon Beck [5] and Pesetsky [44], Soh [54] proposes that in situ weishenme ‘why’ undergoes covert feature movement at LF. According to Soh, intervention effects detect the movement of wh-feature, such that the feature cannot be separated from what’s left behind on the wh-phrase by a scope-bearing element. Cheng [11] echoes Soh’s solution, taking intervention effects as one crucial piece of evidence for the existence of covert feature movement.

Yang [63, 64] reformulates the covert feature movement approach in terms of the framework of Relativized Minimality [47,48,49]. In a nutshell, intervention is a minimality effect, in which the quantificational ‘likeness’ between a quantifier and the interrogative phrase weishenme ‘why’ means that the feature of weishenme is attracted to the left periphery scope position only if it is closer to the scope position than the quantifier is. Yang borrows from recent works of Starke [55] and Rizzi [49] on Relativized Minimality and provides the following condition, in which the minimality effect is captured in terms of a filter:

If a scopal element A bears feature [F1] and moves to its left periphery scope position, and if another scopal element B has the feature geometry that includes the bundle [F1 F2], then the movement of A from its initial merge position to its scope position is blocked because the bundle [F1 F2] maximally matches [F1]. In other words, the filter condition rules out the scope-taking of an operator at the left periphery when a ‘like’ operator is closer to the scope position of said operator.

The criteria of operator type matching are determined as follows (Rizzi [49]: 19):

Based on this classification, quantifiers as well as focus-sensitive phrases (focus) possess the same quantificational feature as the interrogative operator (Wh). Apart from the quantificational feature, quantifier/focus also bear other features. In a [quantifier < Wh] configuration, the maximal matching filter is violated during the covert feature movement, because Wh’s quantificational feature is maximally matched by the intervening quantifier.

Other wh-phrases such as shenme ‘what’ and zenme ‘how’ do not cause intervention in the same way as weishenme ‘why’ [56]. For Soh [54], the absence of intervention is because these wh-phrases undergo covert phrasal movement, rather than feature movement. In phrasal movement, entire wh-phrases are pied-piped across quantificational interveners. As such, there is no separation between wh-feature and the restriction on wh-phrases [44]. Yang [64] accounts for the absence of intervention by resorting to the mechanism of unselective binding [43]. For instance, Yang cites Cheng and Rooryck [12] and endorses the view that wh-phrases have the option of being licensed at a distance by a Q operator that merges directly at [Spec, CP]. According to this view, in weishenme ‘why’-questions, intervention arises because the weishenme-adjunct does not possess this option, and ergo must be licensed via covert feature movement. In contrast, other wh-phrases can be licensed by unselective binding and undergo no movement, in which case the maximal matching filter is vacuously satisfied and no intervention arises. Note in addition that Yang’s framework is also compatible with a covert phrasal movement solution: Pied-piped wh-phrases may be argued to bear more features than intervening quantifiers, therefore the maximal matching filter is not violated, unlike in feature movement.

The minimality-based approach as specified above is problematic upon closer scrutiny. This is because the minimality approach treats all quantifiers (both quantificational nominal phrases and adverbs of quantification) as legitimate interveners that block the LF movement of an interrogative operator. Quantifiers are interveners, simply because they bear a quantificational feature. Therefore, this approach would not predict the Chinese intervention pattern, where the intervention is sensitive to the types of quantifiers. Instead, the approach as it stands should predict that a finer distinction within quantifier types will not make any difference in intervention. If quantifiers in general possess enough features to maximally match the interrogative operator, then by including monotonicity as a further dimension in the feature geometry we only increase the inventory of the feature set for the quantifiers. Therefore, both monotone increasing and decreasing quantifiers are supposed to maximally match the interrogative operator and block its covert movement. Furthermore, it is rather stipulative if we bring monotonicity into our feature geometry, especially given that we find no independent evidence that monotonicity plays a role in other intervention environments (i.e., those involving non-why interrogative questions). Given the lack of apparatus to allow only a subset of quantifiers to block covert LF movement, it seems that the validity of a minimality account is in question. Finally, in embedded questions, a minimality account predicts that the covert interrogative operator still moves to take the embedded [Spec, CP] scope position (crossing the quantificational interveners along the way). Hence, even assuming that quantifier types can be fine-tuned to accommodate the intervention data in matrix questions that we have seen in (2)–(4), it is mysterious how a minimality account handles the selective amelioration phenomenon in the embedded questions of (5)–(7) in a principled manner.

The restricted set of quantificational interveners, i.e., downward quantifiers only, is reminiscent of another intervention environment that has received rich treatment, namely negative islands. It thus evokes the possibility that the intervention phenomenon in Chinese is subsumed under negative island sensitivity. A full survey of this connection is not available in the literature, in part due to the lack of dedicated literature of negative islands in Chinese. At present, I would like to point out that why is generally excluded from discussions of negative islands for being rather ‘atypical’. Both Szabolcsi and Zwarts [58] and Abrusán [1] explicitly rule out why-questions in their theories of negative islands, noticing that why differs from other wh-adjuncts in that its extraction is blocked in a wider range of environments than others, suggesting that why independently favors late insertion/high attachment in the structure. The idiosyncratic structural property of why will be discussed in the following.Footnote 5

3 A Semantic Account of the Intervention Effects in Chinese Why-Questions

3.1 The Syntax and Semantics of weishenme ‘Why’

In this section, I build on previous observations that the reason/cause wh-adjunct why behaves in a different way from other wh-phrases. Following Ko [33], I assume that, crosslinguistically, why-adverbs favor high merge. Specifically, the East Asian (Chinese, Japanese, Korean, etc.) counterparts of why are directly merged at [Spec, CP], as opposed to other wh-phrases that are moved to [Spec, CP] from a lower initial merge position. In what follows, I cite a few published data that motivate the above treatment. As early as Lawler [40], it has been proposed that, in a why-question, why does not associate with any variables in the clause that it attaches to. For example, in the following mono-clausal sentence, it has been proposed that why does not bind a trace that links to the VP leave [48].

The no-trace property of why is seen more clearly in (14). As Lawler [40] points out, only one reading is available in the following quantificational environment:

In reading A, an event, three men left, is presupposed. By wondering why this event occurs, we are committed to a situation in which the total number of people that left has to be three. In reading B, it is also the case that a group of three individuals left. Yet there is no requirement that, in this situation, altogether three people left. There could be other individuals who left, but for some reason the speaker is only concerned with a specific group of three people. When it happens that only three people left in the context, the two readings are not distinguishable. Crucially, however, when the context contains more than three individuals having left, the why-question in (14) cannot be uttered, at least according to the speakers Lawler [40] consulted.

Furthermore, it has been observed that why cannot be associated with the embedded clause (or the long-distance construal), and can only be associated with the matrix clause (or the short-distance construal). This can be exemplified by the examples in (15) [10, 41].

Bromberger [9] argues that the above data would again follow if why merges directly to its scope position, and cannot be incorporated into the rest of the sentence by means of a trace. Bromberger points out a further piece of evidence, in which why and other wh-phrases interact with scopal elements such as focus operators in different ways.

Here I use small caps to mark that Adam is a focussed constituent. While (16a) presupposes that only Adam ate the apples, (16b) is compatible with the reading in which every individual ate the apples at different times, and the speaker is simply concerned with the time of Adam’s eating event. Bromberger [9] argues that we can account for the reading in (16b) if we assume that when is base-generated in a position below the focus operator and that it binds a trace after it undergoes movement. Let’s assume that the focus operator provides a focus value against a set of alternatives. That is, we first have a set of alternatives in the form of {x eat the apples when | x ranges over contextually relevant individuals}. The focus operator then applies to the set of alternatives, setting the value of x to Adam (In Bromberger’s representation: (Wheni) {(\(\exists \)x: x = Adam){x ate the apples at ti}}). On the other hand, if why leaves behind no trace and directly merges above the scope of the focus operator, then the focus value will be set to Adam first, before we use why to ask for the reason (In Bromberger’s representation: (Why) {(\(\exists \)x: x = Adam){x ate the apples}}). As a result, a why-question presupposes that only Adam, out of all individuals, ate the apples.

Related to the above observations, Tomioka (2009) demonstrates that, in downward entailing environments, why triggers different presuppositions from other wh-phrases. Compare (17a) with (17b), taken from Japanese.

In line with the above observations, Tomioka formulates the following semantic constraint for why:

This constraint calls for a high merge position of why, which Ko [33] assumes to be [Spec, CP]. Ko’s proposal is exclusively about counterparts of why in East Asian languages such as Chinese, Japanese and Korean. Independently, Rizzi [48] argues that perché ‘why’ in Italian merges directly at [Spec, IntP]. Rizzi assumes that the head of IntP carries a [+wh] feature inherently, therefore this direct high merge explains why perché does not trigger auxiliary inversion. Given that there is no motivation for a structural distinction between [Spec, CP] and [Spec, IntP] in East Asian languages, we can essentially consider Rizzi’s high attachment analysis of perché the same as Ko’s proposal for East Asian whys. What is important for our current purpose is that both [Spec, CP] and [Spec, IntP] are higher than the scope positions of the focus operator and quantifiers at the left periphery (according to Rizzi), thus capturing the readings such as in (16) and (17).

3.2 Quantifiers as Plural Indefinites

If Chinese weishenme ‘why’ directly merges at [Spec, CP], it does not take part in quantifier scope interactions, because it is directly interpreted at a scope position above quantifier scope. Moreover, Chinese is known to observe a scope isomorphism at the left periphery, such that scopal relations at LF are preserved at surface syntax [2, 21]. Unlike Japanese or Korean, Chinese quantifiers cannot scramble across outscoping operators to create a mismatch between word order and scope order [33]. Therefore, we would expect that quantificational elements, when taking scope as a generalized quantifier, be c-commanded by weishenme. However, in (19a-b), we see that weishenme and quantifiers may occur in two relative orderings.

In (19a), where weishenme c-commands the quantifier duoshu ren ‘most people’, we obtain an expected reading in which the latter denotes a standard GQ meaning, and weishenme takes the entire quantified proposition as its argument. Importantly, the question in (19b) does not seem to involve a generalized quantifier that scopes below weishenme. What (19b) asks is the reason that causes one particular plurality of individuals to resign, and this plurality has to be a majority subset of all the context-relevant individuals. For (19a), an answer can be given in the form of (20):

Meanwhile, (20) cannot be an answer for (19b). A felicitous answer must provide a reason of resignation for a particular plurality of individuals. Therefore, the reading of (19b) suggests that most people receives the interpretation of a plural indefinite and exhibits exceptional wide scope, above the scope of why, which is characteristic of plural indefinites. Both Reinhart and Winter have proposed that quantifier phrases such as some people or many people can be interpreted as plural indefinites, in which they do not denote a relation between predicates, in the traditional sense of Barwise and Cooper [4]. Rather, they denote individuals, by being coerced into a minimal witness set [19].Footnote 6

In this paper, I propose that most people may also denote a plural indefinite. To go one step further, I argue that the plural indefinite most people is a topic when it takes wide scope over weishenme ‘why’. That is, I believe that exceptional wide scope is a topic phenomenon [19]. A topical reading is possible for quantifiers interpreted as plural indefinites, because all referring expressions that are individual-denoting may serve as topics under the right contextual conditions. Importantly, I argue that topics are able to take scope outside of a speech act (that is, they may scope above the illocutionary operator of a sentence). As such, topics scope above the high initial merge position of weishenme in a weishenme-question. This accounts for the exceptional wide scope position of plural indefinites.

3.3 The Wide Scope Behavior of Topical Quantifiers: Some Evidence

Below I present evidence that topics are able to take scope outside speech acts. In the next section, I show that the ability for quantifiers to be topics depends on their monotonicity. Various authors have pointed out that if any part of a proposition is capable of scoping out of a speech act, it will have to be a topic [18, 36, 45]. This is because topic establishment is a separate speech act by itself. The idea that topics are assigned illocutionary operators of their own is first raised in Jacobs [31]. Jacobs points out that introducing a topic is an act of frame setting. In the following, I follow Krifka’s recent position that natural language allows speech acts to conjoin. A topic-comment structure expresses two sequential, conjoined speech acts, comprising the topic’s referring act, to be followed by a basic speech act (assertion, request, command, etc.) that is performed as an update on the referent established by the topic. Krifka [36] notes that, in English, overt devices are used to mark topics as scoping out of questions, commands and curses, such as the following:

According to Krifka, topics even have to scope out of speech acts, given that they function as a separate speech act. In Chinese, if we assume that the topic act conjoins with a subsequent request speech act performed by a weishenme-question, we would predict that all the expressions that may serve as topics may occur outside the scope of weishenme without causing intervention. This prediction is borne out. As (22) demonstrates, proper names, pronouns and temporal/locative adverbs can legitimately c-command weishenme. These are expressions that have long been known to allow for a topic reading [21, 39].

Example (22) additionally shows that when multiple topics are co-occurring, they can all c-command weishenme. There seems to be a functionally based cognitive constraint preventing more than three topics from co-occurring in the same sentence in Chinese. But a sentence with three topics is marginally acceptable [62]. In such case, we also find a weishenme-question with three c-commanding topics acceptable:

Furthermore, in biscuit conditionals, an if-antecedent may co-occur with a weishenme-question as its consequent, illustrated in (24):

Various proposals have suggested that the antecedents of biscuit conditionals are topics [18, 20], such that they scope out of the speech act performed by the consequents of the conditionals. If this is valid, then it is readily predicted by our proposal of topic act that the antecedent in (24) is able to scope above a weishenme-consequent.

Another prediction is that if an element is by nature not topical, it will never c-command weishenme. This would readily explain the fact that focus-sensitive expressions also induce intervention in weishenme-questions, since they are known to be strongly anti-topical [59]. The following example demonstrates that focus-sensitive phrases also induce intervention effects in weishenme-questions. Sentence (25a) is unacceptable, because weishenme is c-commanded by the focus sensitive only-NP. (25b) and (25c) are similarly unacceptable, when weishenme is c-commanded by the focus adverbial zhi ‘only’ and the focus particle lian...ye/dou ‘even’.Footnote 7

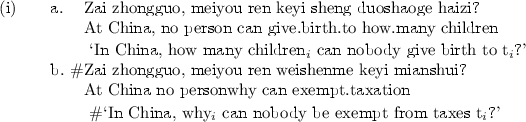

Apart from topics, the second class of subsentential expressions that scopes out of illocution are the epistemic attitude adverbs such as daodi ‘on earth’ and jiujing ‘frankly/honestly’. Importantly, this class of adverbs express epistemic attitude towards speech acts [21, 22, 30]. As such, they are speech act-level modifiers and take the illocutionary operator as their argument. Hence, they fall outside the scope of illocution. In (26), I show that both a speech-act adverb and a topic may precede weishenme:

A contrast exists between this class of speech act-level adverbs and proposition level attitude adverbs such as yiding ‘definitely’ and kongpa ‘probably/most likely’, as we can see below:

Unlike daodi/jiujing, adverbs such as yiding ‘definitely’ indicate the speaker’s attitude towards the propositional content or contents of smaller units, rather than the speaker’s attitude towards the speech act. Interpreting the question operator within the scope of yiding creates a semantic anomaly, because such adverb is not compatible with taking question operators as arguments. In other words, an expression is able to precede weishenme if and only if it is able to take the weishenme-question’s illocutionary operator in its scope. A speech-act level adverb does so by modifying the speech act itself. As such, it patterns with topics and does not cause intervention. Note that I have assumed all along that c-command relation mirrors scopal relation in the Chinese left periphery. This is because long-distance scrambling is impossible in Chinese [21, 29, 33]. Importantly, scrambled operators reconstruct their scopes at LF. In Japanese and Korean, when generalized quantifiers scramble across the why-adjunct at surface syntax, they reconstruct their scope at the trace position [32]. Because reconstruction is not available in Chinese, when quantifiers such as meiyou ren ‘no one’ c-commands weishenme, we cannot receive an interpretation in which meiyou ren is reconstructed below the scope of weishenme.Footnote 8

3.4 Intervention as a Speech Act Constraint

In the above, I present evidence that topics (together with speech act-modifying epistemic attitude adverbs) are able to scope above speech act. In this section, I show that an exceptional wide scope theory of topics renders a straightforward explanation of the intervention in Chinese why-questions.

First, I briefly discuss how a scope theory of topics can be couched in a formally precise framework of speech act establishment and conjoining. Here I follow the Wittgensteinian view that the speech act of a sentence corresponds to a component of the sentence that combines with the sentence radical. The sentence radical can be seen as unsaturated unless attached to the speech act operator [3, 7, 13, 38, 60]. According to Krifka [36], we can define speech act as a semantic object with the basic type a. A speech act operator thus can be seen as taking as input a sentence radical and returning a speech act. For example, the assertion operator ASSERT is of type \(<<\)s,t>, a> (taking as input a proposition, and returning a speech act). The question operator REQUEST is of type \(<<<\)s,t>, t>, a> (taking as input a set of propositions, and returning a speech act). We further assume that natural language allows speech acts to conjoin. A topic-comment structure expresses two sequential, conjoined speech acts, comprising the referring act of a topic, to be followed by a basic speech act (assertion, request, command, etc.) that is performed against the referent as established by the topic. To capture a topic’s referring act, Krifka also posits a referring speech act operator REF of type <e,a>. Finally, & is a conjunction operator that conjoins speech acts (type <a, <a, a\(>>\)). In the case where a question is structured into a topic and a comment question, the sentence performs a conjunction of topic establishment and request, represented as the following:

We can further incorporate speech act, as semantic objects with basic types, within the sentence grammar. Krifka [36] proposes that the speech act operator heads a Speech Act Phrase (SAP) projection that takes the sentence core (CP) as its complement. In the case of topicalization, Krifka proposes that SAPs can be recursively defined. The topic merges to the specifier of the first SAP, the head of which is occupied by another SAP, which is in turn headed by a basic speech act operator taking a CP complement. For instance, in the why-question (29a), I analyze the DP daduoshu ren ‘most people’ as a topical quantifier. Under this analysis, this sentence can be represented as (29b) (QUEST being the label used by Krifka for a request operator).

Finally, I provide a simplified semantics of topical quantifiers used as individual-denoting plural indefinites. To start with, I define a quantifier as witnessable if and only if the quantifier receives a plural indefinite reading, denoting its witness set [16, 19, 46].

Following Reinhart [46] and Winter [61], witnessable quantifiers denote type-e meaning via a covert choice function variable of type \(<<\)e,t>,e> that, given a property (type <e,t>) as input, returns some plurality (type e) that has such property. The quantifiers in individual-denoting DPs are choice function modifiers that add a presuppositional restriction on the cardinality of the entity returned by the function. For example, most is represented as (31).

Here SUM is defined over pluralities that consist of atom individuals. Given a plurality, it outputs the set of all the atoms in the plurality. The witnessable quantifier most people denotes the plurality returned by the choice function f when applied to the property of being a majority of all the context-relevant individuals, represented as follows:

The alternatives generated by ‘[f most] people’ are computed by substituting different choice function variable values in the position of [f most]. Combining these alternatives with the restrictor people, we produce contrasting pluralities of individuals, each of them contain a majority of all the context-relevant individuals. Crucially, I claim that whereas monotone increasing and non-monotonic quantifiers are witnessable, monotone decreasing quantifiers are not witness-able. A non-witnessable quantifier, such as few people, may have a verifiable, non-empty witness set. However, it does not make reference to its witness set by denoting any choice-function selected pluralities.Footnote 9

Now we can derive intervention effects from the interaction of topicalization, conjoined speech acts and witnessability. In a nutshell, if a quantifier is witness-able and hence is able to be construed as topical, it may scope above weishenme. On the other hand, if a quantifier cannot be construed as topical, outscoping would be impossible, due to why’s high scope. Intervention effects would arise in such cases, because for the non-topicalizable quantifier, the ordering of the quantifier preceding weishenme is impossible, hence semantically anomalous. The so-called intervention effects arise when an expression that cannot scope above why nevertheless occupies a wide scope position. In other words, there is no ‘real’ intervention involved here. Rather, the intervention in why-questions should be better characterized as a scope effect. In (33a), the why-question with the quantifier daduoshu ren ‘most people’ is acceptable as it is interpreted with the semantics in (33b). I also provide a less formal paraphrase of the question’s meaning in (33c):

On the contrary, the why-question with the quantifier henshao ren ‘few people’ is unacceptable because henshao ren cannot be a topic. That is, (34a) does not have the interpretation in (34b). Also, the paraphrase in (34c) is an impossible one:

In sum, when we consider quantifiers in terms of topicality, we immediately explain why monotone decreasing quantifiers induce intervention effects in weishenme-questions: they cannot be topical, hence they cannot give rise to coherent readings in weishenme-questions. Non-decreasing quantifiers are unproblematic, because they denote individuals that serve as topics.Footnote 10

Furthermore, this theory claims that bare numerals and monotone increasing modified numerals can be topics. We still need to explain why these numeral quantifiers induce weak intervention, as seen in (35) (repeated from 4):

I believe the weak acceptability in (35) has a pragmatic reason. Following Kratzer [34, 35], I assume that choice function variables receive their values directly from the context of utterance. If context does not readily offer a particular plurality as the value for a choice function variable, the speaker won’t know which plurality to pick out with the quantifier, and oddness arises. In the case of numeral quantifiers, we are required to pick out a particular plurality bearing a specific cardinal number, which would leave the hearers with no clues if there is no further information from the context. Krifka [36] observes the same problem for the English example in (36):

The acceptability is claimed by Krifka to be marginal. This low acceptability of two boys, compared to phrases such as most boys, follows from the fact that it places a higher requirement on the discourse structure and on hearers’ efforts to infer which particular set of two boys are under discussion. Similarly, we can explain why the topical use of quantifiers containing a numeral component is harder. Without explicit context providing supporting information, it is not plausible for a naive hearer to make a partition of the relevant individuals such that one particular plurality of a given cardinality should be distinguished against other individuals.

The context-based claim I have argued above predicts that why-questions with witnessable numeral quantifiers should be acceptable in a plausible scenario. This seems to be indeed the case, as the following example demonstrates.Footnote 11

Finally, embedded questions may offer the contextual information to anchor a particular plurality [57]. I will illustrate with the example in (38) (repeated from example (6)):

The indirect question that serves as the complement of found out does not denote a question type, but rather a fact derived from a question [25, 37]. Specifically, the indirect question is construed as a true answer (true resolution) to the corresponding direct question. Thus, (38) is paraphrased as follows: ‘I already found out (the answer to the question of) for three people, why they resigned.’ Following Rooth [50], this indirect question intuitively answers one subquestion of the overall question: ‘Why did a contextually-salient set of individuals resign?’ In order to answer this overall question based on the knowledge of the speaker, the question is partitioned into two contrasting subquestions. The first asks about a plurality consisting of three people, of whom the speaker has knowledge about. The other asks about ‘the rest of the individuals’ of whom the speaker does not provide an answer due to lack of knowledge.

3.5 Further Evidence for the Type-e Meaning of Topical Quantifiers

In this section, I present evidence that the topicality of quantifiers correlates with their monotonicity. My diagnostics are based on Constant [15, 17]. First, Constant notices that only witnessable quantifiers (monotone increasing and non-monotonic) may serve as contrastive topics. In (39), I put forward Chinese data in support of Constant’s claim (CT for contrastive topic, F for focus):

In (39), monotone increasing quantifiers serve as contrastive topics, but monotone decreasing quantifiers cannot. If CT-marked quantifiers such as most only have a standard GQ reading, they would be construed as answering one of the subquestions of question A. These subquestions would be the alternatives in {Where did most grads live? Where did a few grads live? Where did no grads live?...}Footnote 12 This does not accord with our intuition, in which B’s answer means that B has information about where a majority subset of individuals live, as opposed to the rest of the individuals about whom B has no information. If most grads denotes a specific plurality of individuals, then the contrasting alternatives will be between different individual grads. This seems to be exactly what (39) does. Furthermore, if CT-marked quantifiers are standard GQs, it would be mysterious why quantifiers such as few cannot form an answer. If we subscribe to a choice functional approach, on the other hand, the reason is obvious, since few cannot denote a choice-function-selected plurality. If quantifiers such as few lack choice-functional interpretations, then an answer in (39B) with few only has the standard GQ reading. If we assume that CT is simply unable to contrast quantifiers of this type, then the sentence will be ruled out.

One further piece of evidence given by Constant is that quantifiers differ in their ability to appear in equative copular constructions: In an equative construction, the two-place copula be equates two individual-denoting expressions. On the left side, the first argument of the copula is a type-e plurality DP. For the equative construction to be well-formed, the right argument needs also to be an individual-denoting plurality DP. Therefore, the equative construction provides yet another diagnostic on which quantifier qualifies as type-e denoting. As it turns out, the judgment patterns in (40) match well with the patterns we have seen in the contrastive topic diagnostic.

4 Conclusion

This paper develops an account of intervention effects with Chinese weishenme ‘why’ and monotone decreasing quantifiers. The empirical generalization is that monotone decreasing quantifiers cannot scope above weishenme at surface, with weishenme ‘intervening’ between those quantifiers and the rest of the sentence. My take on this issue is to propose a new way of looking at things. Weishenme is not only in situ, but also at the position where it, syntactically speaking, checks off the wh-feature, and where it, semantically speaking, is interpreted. Materials to the left can only be interpreted as topics, giving rise to a secondary speech act in the sense of Krifka [36]. Using a notion of topicality involving witnessability (in the sense of Reinhart [46]), I then derive the quantifier restriction for this position based on which determiners can lead to witnessability, thus excluding monotone decreasing quantifiers. Quantificational expressions with monotone increasing numerals, as well as bare numerals, are also not acceptable in apparent intervention configurations, unless these sentences are embedded. I argue that this is due to the lack of context in root sentences, thus leaving the choice function variables without a value. In sum, the current analysis combines relatively independently but under a theoretical perspective disparate ideas, and arrives at a novel and simple solution to a rich array of empirical facts.

Notes

- 1.

- 2.

The glossing in this paper follows the Leipzig Glossing Rules (https://www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/resources/glossing-rules.php). A list of the abbreviations in this paper is given as follows:

ACC: accusative; CLF: classifier; COP: copula; DEM: demonstrative; NEG: negative, negation; NOM: nominative; LOC: locative; PASS: passive; PL: plural; POSS: possessive; PRF: perfect; PRS: present; PRT: particle; PST: past; Q: question particle; REL: relativizer; RES: resultative; TOP: topic marker.

- 3.

Based on monotonicity, I treat the Chinese quantifier henshao ren as an equivalent of few people, since both require a less-than-half cardinality reading and are monotone decreasing. Furthermore, I treat shaoshu ren as an equivalent of a few people, as they pattern together as non-monotonic quantifiers with a less-than-half reading. It is also worth noting that a few people/shaoshu ren generally give rise to a non-empty scalar implicature (see Horn [28]), whereas few people/henshao ren generally do not.

- 4.

Consequently, I choose to put a # sign before unacceptable Chinese why-question sentences as well as their English translations to indicate that the examples are odd because the readings they generate are semantically anomalous. However, I still consistently use the term ‘intervention effects’ to refer to the types of phenomena that are already well established in the tradition, without taking this term in its literal sense.

- 5.

On a separate note, the modal obviation effect that is associated with negative islands (cf. Abrusán [1]) is absent in Chinese why-questions. In (ia), I show that adding the modal keyi ‘can/might’ circumvents the negative islands in a how many-question. In (ib), in contrast, I show that adding the same modal fails to improve a why-question.

If the modal obviation effects, as the majority of accounts of negative islands assume, serve as a diagnostic for islandhood in negative contexts, then the contrast in (ia-b) provides additional evidence that the intervention pattern witnessed in why-questions is a different beast.

- 6.

- 7.

In (25a), zhiyou ‘only’ forms a constituent with an NP and assigns focus value to the NP. In (25b), zhi ‘only’ is a focus adverb. The lian + NP + ye/dou construction in (25c) is often assumed to be the Chinese counterpart of the English focus-sensitive even-NP [27, 42, 52]. It seems that lian and ye/dou together contribute to the semantics of the English focus particle even, although the exact nature of the division of labor is still not clear. According to some analyses, lian assigns focus accent to the NP it combines with, and ye/dou is a maximality operator that overtly expresses the alternatives in the focus value [24].

- 8.

- 9.

Independently, experimental results show that the monotonicity of a quantifier affects its ability to entail a witness set due to processing reasons [8, 23]. To verify a quantified sentence containing most or more than two, one needs to find positive instances that members within the restrictor set satisfy the most-relation, the more-than-two-relation, etc. In other words, one needs to verify the existence of a witness set. In contrast, for quantified sentences with no, few, or less than two, the verification procedure more often requires drawing a negative inference based on the absence of positive instances (in which case the witness set is empty). Although there is still a paucity of relevant work on this topic, the intuition is that monotone decreasing quantifiers are not an informative way to denote a witness set.

- 10.

We should expect that the topicality constraint thus formulated applies even in the absence of weishenme ‘why’, since the topic position is generally available. This prediction is borne out. As mentioned above, the class of epistemic attitude adverbs such as daodi ‘on earth’ and jiujing ‘frankly/honestly’ take scope above speech act operators. This class of adverbs can be used to identify topic positions, in the absence of weishenme ‘why’, because when a quantified expression precedes this class of adverbs, the quantified expression has to reside outside the speech act of the sentence it occurs with and thus must receive a topical reading rather than a GQ reading. Importantly, as (i) shows, monotone decreasing quantifiers induce intervention when they precede epistemic adverbs even in non-why questions. Intervention is absent for non-decreasing quantifiers.

It thus seems that we can indeed reduce the ‘intervention’ in why-questions to a broad phenomenon of topicalizability.

- 11.

According to my consultants, if we use a non-partitive form zhishao san-ge shangyuan ‘at least three injured players’, the sentence is still mildly acceptable, but nowhere close to the fine judgments we are getting with the partitive quantified expression in (37). Note that Constant [15, 17] also notices (without suggesting an explanation) that partitive forms of quantifiers more readily license a referential reading than non-partitive forms. At present, I do not know how to account for this, and have to leave an answer to future work.

- 12.

See Rooth [50] for a discussion of how contrastive topic-marked answer is answering a subquestion of a preceding overall question.

References

Abrusán, M.: Presuppositional and negative islands: a semantic account. Nat. Lang. Semant. 3(19), 257–321 (2011)

Aoun, J., Li, A.: On some differences between Chinese and Japanese wh-elements. Nat. Lang. Semant. 24(2), 365–372 (1993)

Åqvist, L.: A new approach to the logical theory of actions and causality. In: Stenlund, S., Henschen-Dahlquist, A.-M., Lindahl, L., Nordenfelt, L., Odelstad, J. (eds.) Logical Theory and Semantic Analysis, pp. 73–91. Springer, Dordrecht (1974)

Barwise, J., Cooper, R.: Generalized quantifiers and natural language. Linguist. Philos. 4(2), 159–219 (1981)

Beck, S.: Intervention effects follow from focus interpretation. Nat. Lang. Semant. 14(1), 1–56 (2006)

Beck, S., Kim, S.-S.: Intervention effects in alternative questions. Nat. Lang. Semant. 9(3), 165–208 (2006)

Belnap, N.: Questions: their presuppositions, and how they can fail to arise. In: Lambert, K. (ed.) The Logical Way of Doing Things, pp. 23–37. Yale University Press, New Haven (1969)

Bott, O., Klein, U., Schlotterbeck, F.: Witness sets, polarity reversal and the processing of quantified sentences. In: Aloni, M., Franke, M., Roelofson, F. (eds.) Proceedings of the 19th Amsterdam Colloquium, pp. 59–66 (2013)

Bromberger, S.: On What We Know We Don’t Know: Explanation, Theory, Linguistics, and How Questions Shape Them. University of Chicago Press, Chicago (1992)

Cattell, R.: On the source of interrogative adverbs. Nat. Lang. Semant. 54(1), 61–77 (1978)

Cheng, L.: Wh-in-situ, from the 1980s to now. Nat. Lang. Semant. 3(3), 767–791 (2009)

Cheng, L., Rooryck, J.: Licensing wh-in-situ. Nat. Lang. Semant. 3(1), 1–19 (2000)

Chierchia, G.: Questions with quantifiers. Nat. Lang. Semant. 1(2), 181–234 (1993)

Choe, H.S.: Syntactic wh-movement in Korean and licensing. In: Theoretical Issues in Korean Linguistics, pp. 275–302 (1994)

Constant, N.: On the positioning of Mandarin contrastive topic -ne. In: (Workshop) Information Structure, Word Order: Focusing on Asian Languages (2013)

Constant, N.: Witnessable quantiers license type-e meaning: Evidence from contrastive topic, equatives and supplements. In: Proceedings of Semantics and Linguistic Theory, pp. 286–306 (2013)

Constant, N.: Contrastive topic: meanings and realizations. Ph.D. thesis (2014)

Ebert, C., Ebert, C., Hinterwimmer, S.: A unified analysis of conditionals as topics. Linguist. Philos. 37(5), 353–408 (2014)

Endriss, C.: Exceptional wide scope. In: Endriss, C. (ed.) Quantificational Topics. Springer, Dordrecht (2009)

Endriss, C., Hinterwimmer, S.: Direct and indirect aboutness topics. Linguist. Philos. 55(3–4), 297–307 (2008)

Ernst, T.: Conditions on Chinese A-not-A questions. J. East Asian Linguist. 3(3), 241–264 (1994)

Ernst, T.: The Syntax of Adjuncts. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2001)

Geurts, B., van der Slik, F.: Monotonicity and processing load. J. East Asian Linguist. 22(1), 97–117 (2005)

Giannakidou, A., Cheng, L.: (In) definiteness, polarity, and the role of wh-morphology in free choice. J. East Asian Linguist. 23(2), 135–183 (2006)

Ginzburg, J., Sag, I.: Interrogative Investigations. CSLI Publications, Stanford (2000)

Grewendorf, G., Sabel, J.: Scrambling in German and Japanese: adjunction versus multiple specifiers. J. East Asian Linguist. 17(1), 1–65 (1999)

Hole, D.: Focus and Background Marking in Mandarin Chinese. Routledge, London (2004)

Horn, L.: The border wars: a Neo-Gricean perspective. In: von Heusinger, K., Turner, K. (eds.) Where Semantics Meets Pragmatics, pp. 21–48. Elsevier, Amsterdam (2006)

Huang, J.: Move WH in a language without WH movement. J. East Asian Linguist. 1(4), 369–416 (1982)

Jackendoff, R.: Semantic Interpretation in Generative Grammar. MIT Press, Cambridge (1972)

Jacobs, J.: Funktionale satzperspecktive und illokutionssemantik. Linguistische Berichte 91, 25–58 (1984)

Kitagawa, Y.: Anti-scrambling. Manuscript, University of Rochester (1990)

Ko, H.: Syntax of why-in-situ: merge into. Nat. Lang. Linguist. Theor. 23(4), 867–916 (2005)

Kratzer, A.: Scope or pseudoscope? Are there wide-scope indefinites? In: Rothstein, S. (ed.) Events and Grammar, pp. 163–196. Springer, Dordrecht (1998)

Kratzer, A.: A note on choice functions in context. Manuscript, UMass Amherst (2003)

Krifka, M.: Quantifying into question acts. Nat. Lang. Semant. 9(1), 1–40 (2001)

Lahiri, U.: Questions and Answers in Embedded Contexts. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2002)

Lang, E., Steinitz, R.: Können Satzadverbiale performativ gebraucht werden. In: Motsch, W. (ed.) Kontexte der Grammatiktheorie, pp. 51–80. Akademie Verlag, Berlin (1978)

Law, P.: Adverbs in A-not-A questions in Mandarin Chinese. J. East Asian Linguist. 15(2), 97–136 (2006)

Lawler, J.: Any question, pp. 163–173 (1971)

Oshima, D.Y.: On factive islands: pragmatic anomaly vs. pragmatic infelicity. In: Washio, T., Satoh, K., Takeda, H., Inokuchi, A. (eds.) JSAI 2006. LNCS (LNAI), vol. 4384, pp. 147–161. Springer, Heidelberg (2007). doi:10.1007/978-3-540-69902-6_14

Paris, M.-C.: Nominalization in Mandarin Chinese: the morphene “de” and the “shi” ... “de” constructions. Ph.D. thesis, Université de Paris 7 (1979)

Pesetsky, D.: Wh-in-situ: movement and unselective binding. In: Reuland, E., ter Meulen, A. (eds.) The Representation of (In) Definiteness, pp. 98–129. MIT Press, Cambridge (1987)

Pesetsky, D.: Phrasal Movement and Its Kin. MIT Press, Cambridge (2000)

Reinhart, T.: Pragmatics and linguistics: an analysis of sentence topics in pragmatics and philosophy. J. East Asian Linguist. 27(1), 53–94 (1981)

Reinhart, T.: Quantifier scope: how labor is divided between QR and choice functions. Linguist. Philos. 20(4), 335–397 (1997)

Rizzi, L.: Relativized Minimality. MIT Press, Cambridge (1990)

Rizzi, L.: On the position Int(errogative) in the left periphery of the clause. Linguist. Philos. 14, 267–296 (2001)

Rizzi, L.: Locality and left periphery. In: Belletti, A. (ed.) Structures and Beyond: The Cartography of Syntactic Structures, vol. 3, pp. 223–251. Oxford University Press, Oxford-New York (2004)

Rooth, M.: Topic accents on quantifiers. In: Carlson, G., Pelletier, F.J. (eds.) Reference and Quantification: The Partee Effect, pp. 1–23. CSLI Publications, Stanford (2005)

Saito, M.: Long distance scrambling in Japanese. J. East Asian Linguist. 1(1), 69–118 (1992)

Shyu, S.-I.: The syntax of focus and topic in Chinese. Ph.D. thesis, University of Southern California (1995)

Soh, H.L.: Object scrambling in Chinese. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (1998)

Soh, H.L.: Wh-in-situ in Mandarin Chinese. J. East Asian Linguist. 36(1), 143–155 (2005)

Starke, M.: Move dissolves into merge: a theory of locality. Ph.D. thesis, University of Geneva (2001)

Stepanov, A., Tsai, W.-T.D.: Cartography and licensing of wh-adjuncts: a cross-linguistic perspective. Nat. Lang. Linguist. Theor. 26(3), 589–638 (2008)

Szabolcsi, A.: Quantification. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2010)

Szabolcsi, A., Zwarts, F.: Weak islands and an algebraic semantics for scope taking. J. East Asian Linguist. 1(3), 235–284 (1993)

Tomioka, S.: Pragmatics of LF intervention effects. J. Pragmat. 39(9), 1570–1590 (2007)

Wachowicz, K.: Q-morpheme hypothesis, performative analysis and an alternative. Questions, pp. 151–163. Springer, Dordrecht (1978)

Winter, Y.: Choice functions and the scopal semantics of indefinites. Linguist. Philos. 20(4), 399–467 (1997)

Xu, L.: Topicalization in Asian languages. In: van Riemsdijk, H., Everaert, M. (eds.) The Blackwell companion to syntax, pp. 137–174. Wiley Blackwell, London (2006)

Yang, B.: Intervention effects and the covert component of grammar. Ph.D. thesis, National Tsinghua University (2009)

Yang, B.: Intervention effects and wh-construals. J. East Asian Linguist. 21(1), 43–87 (2011)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany

About this paper

Cite this paper

Jin, D. (2017). A Semantic Account of the Intervention Effects in Chinese Why-Questions. In: Hansen, H., Murray, S., Sadrzadeh, M., Zeevat, H. (eds) Logic, Language, and Computation. TbiLLC 2015. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 10148. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-54332-0_5

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-54332-0_5

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg

Print ISBN: 978-3-662-54331-3

Online ISBN: 978-3-662-54332-0

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)