Abstract

Unlike typical wh-questions, why-questions are known to be focus-sensitive, but the linguistic realization of their focus sensitivity shows an unexpected pattern in Japanese. The phrase that immediately follows a causal wh-phrase can be considered as the focus associate without any focal prominence. This prosodic pattern contradicts the generally accepted view that a focused phrase invariably receives focal prominence (pitch boost) in Japanese. The paper presents an analysis based on focus movement for this surprising prosodic pattern. We characterize the focus sensitivity of a why-question as an association-with-focus effect with the silent focus exhaustivity operator. The adjacency of a causal wh-phrase and the focus associate is a result of the focus movement to the operator position, which mimics the focus movement proposed by some of the advocates of focus association by movement (Krifka in The Architecture of Focus 82:105, 2006; Wagner in Natural Language Semantics 14(4):297-324, 2006; as reported by Erlewine (Movement out of focus, 2014)). We argue that the adjacency strategy, which places a focus associate immediately after why, is a syntactic manifestation of association with focus, and that this structural disambiguation makes prosodic marking unnecessary. The proposal brings a functional perspective to the syntax–semantics–prosody correspondence in such a way that a focus-marked phrase does not automatically lead to prosodic prominence and the phonological interpretation of focus is influenced by the consideration of usefulness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In the majority of natural languages, focused items are assigned prosodic prominence of various kinds (e.g., stress, higher pitch, longer duration), and Japanese is no exception. There are two specific prosodic phenomena that have been reported in connection to focus in Japanese. One is ‘focal F\(_0\) rise’, in which the pitch (F\(_0\)-peak) of a focused item in a sentence is raised. The second process is ‘post-focal reduction’, a process which reduces the F\(_0\)-peaks of the material that follows the focus. Opinions differ on how these effects should be characterized theoretically. In particular, it is hotly debated whether focus prosody in Japanese is derived via phonological phrasing (e.g., Pierrehumbert and Beckman 1988; Nagahara 1994; Truckenbrodt 1995; Selkirk 2006) or a mechanism independent of phonological phrasing (e.g., Poser 1984; Shinya 1999; Féry and Ishihara 2010; Ishihara 2011). At the descriptive level, however, the pitch boost and the prosodic reduction are universally acknowledged as necessary and indispensable ingredients of focus prosody in Japanese. By closely examining the focus sensitivity of why-questions in Japanese, we present the first systematic counterexample against this descriptive generalization.

Bromberger (1992) observes that, unlike other wh-interrogative sentences, the interpretation of a why-question is affected by focus whereas other wh-questions do not show comparable variability.

As seen in (1), the difference in the location of focus in why-questions leads to the different answers. No such effects are found in (2) and (3). The a and b versions may differ in terms of what kind of discourse context they should be asked in, but the answers do not vary. The correct answer to the a question is the correct answer to the b question.Footnote 1

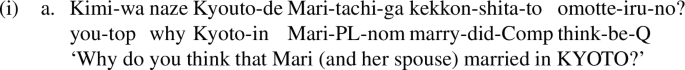

Japanese can employ a similar prosodic strategy to express the focus sensitivity of why-questions, as illustrated below.Footnote 2

(4a) would prompt such an answer as, ‘because both of them wanted to visit Kyoto’, whereas one might respond to (4b) with an answer like ‘because Mana was the only person who was free that day’. In these examples, the causal wh-phrases are placed sentence-initially and receive focal prominence. The focalization of the causal wh-phrases is not surprising at all, as wh-phrases are assigned focal prominence in constituent questions in Japanese. Their focus associates, Kyouto in (4a) and Mana in (4b), are not adjacent to the wh-phrases, and they are also prosodically marked by raised pitch. In other words, the prosodic manifestation of focus association in (4ab) shows the same pattern as focus-sensitive why-questions do in English.

There is, however, another strategy to express focus sensitivity in a Japanese why-question: a causal wh-phrase is placed immediately before its focus associate. In (5ab) below, for example, the phrases immediately following the causal wh-phrase (underlined) are regarded as the focus-associates.

Just as is the case in (4), the wh-phrases in (5) and (6) must bear focal prominence. What is noteworthy, however, is that the focus associates (indicated by underline) need not be assigned any noticeable pitch boost. In other words, by virtue of immediately following why, a phrase can be regarded as the focus associate, and prosodic marking is unnecessary. Despite the lack of prosodic prominence, these questions elicit focus-sensitive answers as (4ab) do. The question naturally arises whether pitch boost is merely unnecessary or is actually prohibited. The answer to this query is rather nuanced and complicated, so we will postpone the discussion of optionality of pitch boost until Sect. 3.2.

Incidentally, Korean shows practically identical patterns. When the causal wh-phrase, way, is at the beginning of a sentence, its non-adjacent focus associate is marked with focal prominence.

It is, however, more commonplace to use the adjacency strategy like the one employed in Japanese—way is placed immediately before the phrase that functions as way’s focus associate (underlined below). Importantly, focus prominence can be absent.

While the observation remains impressionistic, it appears that Korean patterns together in terms of making use of both prosody and adjacency in expressing focus sensitivities in why-questions. With this note, we will focus on the data from Japanese in the remainder of the paper.

The puzzle of the absence of pitch boost carries over to two of the focus-driven syntactic constructions. Kawamura (2007) notes that a causal wh-phrase and its focus associate can be placed together in the pivot (focus) position of the cleft construction, as shown below.

There is one important point that Kawamura leaves unmentioned: As was the case in the ‘in-situ’ adjacency strategy examined earlier, focal prominence falls on why but not on the focus associate.Footnote 3

Even more surprisingly, the same prosodic pattern is found with elliptical why questions, which, at least superficially, resemble what Yoshida et al. 2015 call why stripping.

In Japanese, there are two variants of elliptical why-questions: One involves the copula -da, which takes the form of na/ja in the examples below.

As was the case with the cleft examples above, the wh naze receives focal prominence while the stranded Anna and Maria do not.

In the other type of elliptical why-question, predicative elements are absent altogether, and the focus associate retains the case particle. In the example below, the case particle is the accusative -o, which would be the choice for the presumed verb eran-da ‘choose-Past’.

The prosodic pattern is the same as the first type. Focal prominence falls on naze but not on Anna.

In Yoshida et al. (2015) analysis, the focus marking on the associate of why is critical. In (10), the focalized Anna / Maria move to the left periphery, and the syntactic structure below it undergoes ellipsis. Given that the Japanese counterparts have exactly the same discourse function, it is natural to assume that the same focus marking is involved in (11ab) and (12). Unlike their English counterparts, however, none of the Japanese elliptical why-questions show focal prominence on the focus associates.

The prosodic patterns of why-questions in Japanese (and Korean as well) are puzzling and surprising. First of all, the interpretation of a why-question in Japanese is just as focus-sensitive as that of an English why-question. Moreover, Japanese can express the focus sensitivity in the same way as in English: by appealing to the usual prosodic marking for focus (e.g., 4)). However, the languages have another way of establishing the focus sensitivity, and this second method, which we call the adjacency strategy, expresses the required focus association merely by placing the focus associate immediately after why (e.g. 5)). The two radically different strategies seem functionally equivalent. The two focus-driven syntactic constructions also show a surprising pattern in connection with why. When a focus associate appears in the pivot position of a clefted why-question or is the focused phrase in a why–stripping instance, the associate immediately follows why, and the expected focal pitch accent on the associate is also missing.

We believe that the focus sensitivity in why-questions is not a small glitch in the system but presents a big challenge to the general theory of focus marking in Japanese. What is the source of the adjacency effect, and how does it affect the prosodic marking of focus in the way that makes it unnecessary to assign pitch boost, which is otherwise so predictably present?

2 Focus–sensitivity and exhaustivity

As the first step towards an analysis, let us examine the nature of focus sensitivity in a why-question. Assuming that the semantics/pragmatics of focus sensitivity in a why-question is essentially the same in English and Japanese, we will mostly use data from English. Consider (1) again, which is repeated as (13).

The answer to the first question must explain not only why John bought beer but also why no other people were involved in the purchase. Similarly, the second does not simply ask why beer was bought by John. It asks for the reason why beer was bought, instead of any other beverage that could have been bought. Similar effects are found in ‘free’ foci (= foci without overt focus sensitive operators) in declarative sentences.

In (14), the location of the focus indicates what kind of question the sentence is construed as an exhaustive answer to. (14a) answers exhaustively to Who bought beer for the party? whereas the question of what (beverage) did John buy for the party? would lead to an answer like (14b). Declarative sentences and why-questions also behave alike in that the implicitly negated meaning can be overly asserted or questioned. Suppose, for instance, that there are only two people, John and Andy, under consideration, as these two men are the ones who went shopping.

Given the interpretive similarity between the two uses of focus, it is an attractive idea to identify the focus-affected meaning of a why-question to the exhaustive meaning of focus. One potential complication is, however, that the exhaustivity of a free focus is widely regarded as a conversational implicature and is therefore cancelable, as the following examples illustrate.

Cancelability is not easily tested with a why-question, but the continuation in (17) seems quite infelicitous.Footnote 4

The first step towards accounting for the unexpected contrast in cancelability is to acknowledge that a why-question presupposes the prejacent proposition of why (cf. Tomioka 2009).

When the prejacent of a why-question has a focused phrase in it, the focus is computed within the presupposed content. In other words, it is a case of focus embedded within a ‘given’ constituent. With this understanding of focus in a why-question, the resistance to cancelation is no longer surprising.

The given/presuppositional status of the prejacent of a why-question raises more issues that are relevant to the current discussion. When the condition is right, the prejacent can be elided altogether, resulting in an elliptical/fragmental why-question. It turns out that such a question is also focus-sensitive. Consider the following examples.

There are two important points in (20). First, elliptical why questions are still focus-sensitive, as they ‘inherit’ the focus marking patterns of the antecedent clauses. Thus, a possible answer to (20a) is ‘everyone else was too drunk to drive’ while (20b) might get such an answer as ‘the other car was out of gas.’ Second, the focus sensitivity of an elliptical why-question makes it very hard to defend the hypothesis (e.g., the one pursued by Kawamura 2007) that why itself is focus sensitive. Romero and Han (2004, footnote 15) point out that a focus sensitive operator, such as only, cannot associate into elided contents. In (21), for instance, the antecedent VP contains a focused phrase, but only cannot associate with the corresponding focused phrase in the elided VP.

The following paradigm further highlights the impossibility of focus association into ellipsis.

(22b) shows that focus association can be established under ellipsis if both a focus-sensitive operator and its focus associate are included in ellipsis. (22c) is an acceptable sentence which involves a non-maximal or partial VP ellipsis. Thus, the non-maximal status of the ellipsis in (22a) cannot be the source of its ungrammaticality. It is due to the failure of focus association between only and French, which is the intended focus associate in the elided VP. The fact that focus-sensitive interpretations are successfully generated with the ellipitcal why-questions in (20) indicates that why itself is not creating a focus association. It also hints at the possibility that, if there is a hidden focus sensitive operator in the antecedent clause in A’s utterance, it is part of the elided structure.

Interestingly, an elliptical why-question can be followed by the version with full-fledged structure. In such a case, the focused constituent in the antecedent clause bears focal prominence again, as illustrated below.

This paradigm presents a new puzzle.Footnote 5 On the one hand, an elliptical why-question and its overt counterpart seem to ask the same question, and the second question may function as a ‘reinforcement’ question of some sort. On the other hand, prosodic prominence on the focused phrase is still necessary (or at least highly preferable) when the question is full-fledged.Footnote 6 Therefore, the paradigm above presents a challenge to the prominent idea, pioneered by Tancredi (1992), that ellipsis is closely tied to deaccenting/phonological reduction.Footnote 7 It is also puzzling from the point of view of ‘second occurrence focus’. When a given focused structure is repeated, the second time occurrence of the focused phrase does not receive the kind of prosodic prominence that it does in its first occurrence. While the exact characterization of this second occurrence focus phenomenon is subject to debate (Beaver et al. 2007; Büring 2015; and see Baumann 2016 for overview), second occurrence focus receives significantly reduced prominence.

Although we are not ready to offer a full analysis of this puzzle, it is worth pointing out that the peculiarity of second occurrence free foci is not limited to why-questions. In the following example, the second sentence of B still receives focal prominence on the same phrase as the antecedent clause. Note that the second sentence follows the sentence, ‘I think so’, where the anaphora so clearly indicates the given and semantically identical status of the clausal complement.

Thus, a second occurrence free focus retains prosodic prominence at least in some cases. It may be significant that the second occurrence foci in (23) and (24) are uttered by a different speaker from the speaker of the first occurrence foci. Mysterious though these patterns are, they point to the same conclusion that what is involved in a why-question is a free focus phenomenon in a given context.

The summary of the discussion so far is shown below.

Opinions differ among researchers on how to encode the exhaustive meaning associated with a free focus. We adopt the view that a free focus is not actually free but is associated with a silent operator; an illocutionary operator (Jacobs 1991; Krifka 1994) or a sentential operator that can be embedded, similar to the the scalar-implicature-inducing exhaustive operator of Fox (2007) and Chierchia et al. 2012. In this paper, we use \({exh_F}\), a focus sensitive version of the exhaustive operator (exh) of Fox (2007) and Chierchia et al. 2012. The following is the semantics of this operator.Footnote 8

Footnote 9 What this operator does is to maintain the ordinary value of its complement and add the meaning that all the non-weaker focus-alternatives to the ordinary meaning are false. As mentioned earlier, the second meaning is a conversational implicature that can in principle be canceled. When (26) is applied to (13ab), it yields (27) and (28), respectively.

Let us now think about how the exhaustivity plays out in connection with the meaning of why.Footnote 10 The lexical meaning of a causal wh-phrase is complex. First, we have a question of what kind of semantic object is quantified in a why-question: eventualities, propositions, or some other objects. Another issue is the notion of causation, either in the form of the operator cause or something else (e.g., the concept of explanation). Since complications of these sorts are not central to our current concern, I will remain neutral with regard to these issues. What I would like to concentrate on is the focus-sensitivity of a why-question, and our discussion so far indicates that it is not directly encoded within the meaning of why but is rather due to the presence of \({exh_{ F}}\). We argue that the focus–sensitivity of why is derived by the presence of the exhaustive operator \({exh_{ F}}\) in its immediate scope.

In other words, when a why-question has a focus sensitive interpretation, the exhaustive operator is necessarily projected right below the causal wh-phrase.Footnote 11

3 Focus association

3.1 Association by movement

In Rooth (1985; 1992), the association between a focus-sensitive operator and its focus associate is established ‘in situ’. Particularly relevant are cases where an operator and its associate are physically separated, as in (30).

Roughly speaking, the computation of the meaning of (30a) goes as follows. The focusing on Maria leads to the focus semantic value, which is a non-singleton set of entities including Maria. This set meaning ‘percolates up’ to the VP level, where the focus semantic value of the VP is a set of properties of the form ‘talked to x at the party’. With the adverb only combined with that set meaning, the denotation of the whole sentence is the proposition that for all x, if Anna talked to x at the party, x is Maria. Crucially, no movement of the focused element is assumed. One of the presumed advantages of the in-situ theory of focus association is that no additional assumptions are necessary to analyze cases like (30b) where a focus associate is embedded within a syntactic island.

Although Rooth’s in-situ theory of focus association is adopted by many (e.g., Kratzer 1991; Wold 1996 among others), it is not universally endorsed. An alternative idea that appeals to LF movement has a number of advocates, including Tancredi (1990; 2004); Drubig (1994); Wagner (2006); Krifka (2006); Erlewine (2014); Erlewine and Kotek (2018). These authors point out that the lack of island effects, a major advantage of the in-situ theory, can be accommodated within a movement theory if we assume that an island as a whole moves in a pied-piped fashion. Wagner (2006) argues that association by movement can account for the NPI licensing patterns that the in-situ theory fails to, and Erlewine and Kotek (2018) present evidence in favor of movement based on bound variable interpretations in the Tanglewood sentences, with which Kratzer (1991) originally endorsed the in-situ theory with designated variables and distinguished assignments.

For the purpose of this paper, it is sufficient to acknowledge that association by movement is at least a possible strategy. I therefore adopt the position that the LF movement option is available for why-questions in which why and its focus associate are physically apart. Strictly speaking, a focused phrase does not move to the position of why but rather to the exhaustive operator exh, with which the focused phrase makes a constituent.

This configuration makes it necessary to make some adjustment to the semantic type of \(\textit{exh}_{F}\), as the current assumption that it is a sentential operator does not work under the movement analysis. In the spirit of Wagner’s (2006) and Erlewine and Kotek’s (2018) proposals for only, I propose (32) for the meaning of the movement-triggering exh.

3.2 Association by adjacency

If the desired LF representation of a focus sensitive why-question requires the movement of the focus associate, the adjacency strategy that we have observed earlier obtains a new meaning. Such a structure can be regarded as the surface version of the required LF representation. In other words, it is a preemptive move to create at the level of Spell-Out the configuration that is required at LF.Footnote 12

We are now ready to tackle the critical question: Why does this configuration make focal prominence on the focus associate unnecessary? To answer this question, it is useful to compare (33) with the case of association at a distance.

In this sentence, the focus associate moves to the restrictor position of \({exh_{F}}\) at LF. It is practically identical to the LF representation of (33), in which the relevant structure has already been created before Spell Out.Footnote 13 In (34), it is of vital importance that the intended focus associate is properly and unambiguously marked in one way or another, as there is more than one candidate for association. In such a situation, focal prominence on the intended focus associate is necessary.

This line of reasoning makes it possible to have a novel look at the realization of focal prominence: It is not a result of automatic ‘reading off’ of a focus-feature. Rather, the presence of focus-induced pitch boost indicates which phrase is to be the target of the association with a focus-sensitive operator. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that focal prominence is unnecessary when the intended focus associate is clearly marked in another way. What is remarkable with the adjacency strategy in (33) is that it has already identified via adjacency which phrase is to be associated with the exhaustive operator. Therefore, there arises no need to mark it prosodically.

It is imaginable, however, that the constituent strategy does not eliminate the need for prosodic marking. The case in point is a focus associate within an island. Consider the following examples.

The location of the focus-induced pitch boost triggers the usual effect. (35a) asks for the reason why Anna is looking for the person that Mana met in Kyoto but not the one that other people met in Kyoto. In (35b), on the other hand, the inquiry is about why Anna is looking for the person that Mana met in Kyoto but not the one that she met in other cities. In these examples, the focused phrases are buried within relative clauses. When the adjacency strategy applies to (35ab), the entire complex NP moves to make a constituent with the focus exhaustivity operator because moving the focused phrases out of those complex NPs islands is not allowed.Footnote 14

In this configuration, however, focal prominence is still necessary to distinguish the two readings that correspond to (35ab). Therefore, the focal prominence on the focused phrases is retained, as shown below.

The retention of the focal prominence is also observed in the cleft counterparts of (37ab). This is predicted because the need of prosodic marking for disambiguation is present in the cleft sentences as well.

Let us now look at cases of the adjacency strategy where the focus associate is prosodically focalized. The following sentences would sound more natural without focal prominence on the associates but are certainly not unacceptable.

It should be noted that these sentences are still structurally ambiguous. It is unclear from the word order alone whether the exhaustive operator below why and its focus associate form a constituent or not. For instance, the following is a possible structure.

In this configuration, the focus associate is not specified structurally, as the exhaustive operator and the intended focus associate do not form a constituent on the surface. In the prosodically marked versions we see above, the intended associates may be marked with focal prominence in order to resolve this indeterminacy. We can see this effect even when the causal wh-phrase is placed in a post-subject position. It seems possible, though perhaps not very natural or common, to have a long distance association with a non-adjacent phrase as long as it is focused.

The degree of unnaturalness increases with the clefted and the elliptical why-questions.

The degradation in these examples is predicted under our need-based theory of focal prominence. Unlike the sentences in (39), there is no ambiguity as to which phrase is the focus associate of the focus exhaustivity operator.

To sum up, we have identified the cause of the lack of focal prominence on focus-associates under the constituent strategy. Focus prominence is used to identify which phrase should be associated with the exhaustive operator when the phrase is placed at a distance. The adjacency option makes this need disappear when the focus associate is already structurally identified.

4 On clefted why-questions: Constituency or adjacency?

One issue highlighted by the cleft construction is Kawamura’s (2007) claim that why and its focus associate form a syntactic constituent; and, for her analysis, the facts in the cleft sentences are critically important. As shown earlier in (9), a causal wh-phrase and its focus associate can together sit in the pivot (focus) position of the cleft construction. This fact itself cannot determine whether the two phrases form a constituent or are merely adjacent, as Japanese allows more than one phrase to be clefted in the so-called multiple cleft construction. Kawamura’s argument is based on the case-marking patterns of the focused phrases. When a direct object with the accusative -o is clefted, the object can either drop or retain -o.

This optionality is also observed in a clefted why-question, as shown below.

However, when two phrases are clefted in the multiple cleft construction, the case particles must be retained.

Kawamura concludes that the possibility of case marker drop in (45) is evidence for the constituency of why and its focus associate.

The proposal advocated in this paper does not assume constituency for why and the focus associate. The causal wh-phrase and the focus associate are merely adjacent. Although syntactic constituency is also highly relevant, it is the invisible exhaustive operator, \({exh_F}\), that forms a constituent with the focus associate. The adjacency between why and the focus associate is due to the adjacency between why and \({exh_F}\). Thus, the case-marker drop phenomenon reported above is surprising for the current analysis.

We suggest, however, that the problem can easily be solved within the syntactic structure assumed by our analysis. First of all, it is not clear at all whether why has undergone movement. For instance, the following example, though it sounds slightly odd, is definitely acceptable.

In this example, naze takes the entire clefted sentence as its complement. Therefore, it is not the case that the adjacent option is the only version of clefted why-questions.Footnote 15 The important point that we can draw from (47) is that there is no reason to believe that the structure in (45) involves the clefting of why (along with the focus associate). Instead, it could have been created by inserting why into the clefted sentence, and the pre-pivot position is one of the locations where why can appear.

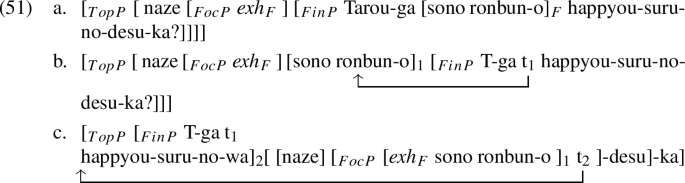

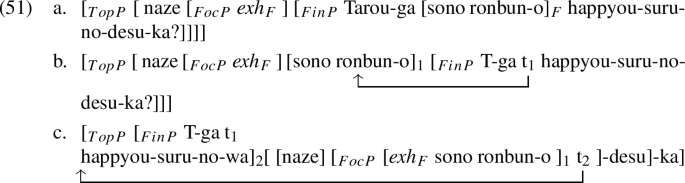

The term ‘insertion’ may be a little misleading, as it sounds as if we had to appeal to a generalized transformational approach. The following is a way to account for the appearance of why in the pre-pivot position. To illustrate, we adopt the mono-clausal analysis of cleft sentences by Hiraiwa and Ishihara (2012). A summary of their analysis is given in (48).

What is presented below is an example of the cleft formation: The cleft sentence (49a) is derived from the non-cleft copula sentence (49b).

Applying this model to why-questions, we make a few additional assumptions. First, the exhaustivity operator, exh, is placed in the specifier of FocP. This also means that the causal wh-phrase adjoins immediately above Focus P (although the cartographic syntax program does not allow adjunction). The input sentence of the clefted why question (45) is shown in (51a) below.Footnote 16 The focus associate moves to FocP to form a constituent with \({exh_{F}}\), as in (51b), and the remaining FinP is topicalized, as in (51c).Footnote 17

We have shown that it is easily possible to analyze a clefted why-question as an ordinary one-phrase clefting structure. The key factor is that naze does not undergo any movement. It is placed right above the FocP that contains \({exh_F}\) in its specifier, which is the target location for the focus movement. This structure makes naze and the focused phrase adjacent but not a syntactic constituent.Footnote 18 Crucially, it is not an instance of a multiple cleft sentence and should pattern together with an ordinary cleft sentence with respect to the case-marker drop process.Footnote 19

5 Fine-tuning the analysis

The analysis proposed for the focus-sensitive why-questions in Japanese advocates the view that the syntax-semantics-prosody mapping has a functional factor. Pitch boost associated with focal prominence can be skipped when prosodic information is deemed unnecessary. It turns out, however, that the necessity of focal prominence must be contextualized in connection with another factor. The cleft construction, discussed in the previous section, plays an important role in this regard. In a declarative cleft sentence, the pivot/focus position typically receives focal prominence, as shown below.

The current version of the functionalist syntax-semantics-prosody mapping would not predict this prosodic pattern since the pre-copula position is structurally designated as the focus position that is interpreted exhaustively. Unless the entire cleft sentence is regarded as old information, as in the clefted why-question in (47), it is necessary to assign focal prominence on the pivot position.

The critical point of (52) is that the pivot, Naoya(-ni), is not only the focus associate of the exhaustivity operator (\(\hbox {Exh}_{F}\)) but also the sentence focus, the notion of focus of the focus–background partition. In other words, Naoya(-ni) corresponds to the wh-expression of the Question-under-Discussion (QUD), ‘Who does Taro want to meet?’. In this sense, Naoya(-ni) is the sentence focus. In addition, its association with the exhaustivity operator (\(\hbox {Exh}_{F}\)) in the cleft makes the sentence the exhaustive answer to the QUD.

On the other hand, the focus of the sentence in a why-question is why itself. According to Krifka (2001b), a constituent question is partitioned based on the information structural properties: the wh-phrase acts as the sentence focus whereas the non-Wh portion of the question corresponds to the background against which the question is asked. Krifka’s idea is also in accordance with our previous assumption that the prejacent of a why-question is presupposed, and that focus is marked within the presupposed content. Therefore, a focus associate in a why-question is not the sentence focus. It is nonetheless focused because the exhaustivity operator requires a non-trivial focus value for its domain. Therefore, we have the following descriptive generalization for focus marking in Japanese. Let us assume that a phrase whose focus semantic value is not a singleton-set (i.e., the focus value is non-trivial) is F-marked.

At this point, we are not ready to claim that the generalization in (53) applies to languages other than Japanese (and possibly Korean). As far as English is concerned, it does not seem to hold.Footnote 20 As shown below, the focus associate of a focus-sensitive operator, such as only, must be prosodically prominent, whether only is placed adjacent to its associate or not.

In these examples, however, the notion of sentence focus is also at play. It is likely that Maria or only Maria is the sentence focus, as either sentence can be an (emphatically) exhaustive answer to the question, ‘Who did Fred introduce to Ned?’. One way to shift the sentence focus to some other constituent is to use a cleft sentence. Consider the following pair.

In (55ab), the pivot Fred is the sentence focus and receives the most prominent stress. The question is whether Maria, which should be associated with only, has a secondary but noticeable stress. The judgment is neither clear nor stable, but the tendency is in accordance with the generalization in (53). (55a) requires some degree of prominence on Maria, as prosody is the only way to establish the focus association. On the other hand, the same kind of prosody is possible but not required in (55b). The lack of discernible prominence seems more tolerated, which is likely due to the unambiguous structure.

6 Conclusion

In this paper, we have examined the ways in which the focus sensitivity of why-questions is expressed in Japanese. Special attention was paid to the adjacency strategy that puts a causal wh-phrase in the immediate proximity of its focus associate, and we have argued for the analysis summarized below.

-

1.

A focus-sensitive why-question is furnished with the focus exhaustive operator (\({exh_{F}}\)) immediately under the causal wh-phrase. Thus, the question asks for the reason/explanation not only for the ordinary semantic denotation but also for why the alternatives in the focus denotation do not hold.

-

2.

Following various proposals that advocate LF focus movement in association with focus, it is claimed that the focus associate of why moves to form a constituent with the exhaustive operator. In this sense, the relevant focus association is not directly with why itself but with \({exh_{F}}\).

-

3.

The focus movement can take place either at LF or before Spell Out. With the former strategy, the focus associate must be identified properly, and focal prominence is a necessary tool for this purpose. If the latter is chosen, however, the identification of the focus associate is done by adjacency. Since it forms a constituent with \({exh_{F}}\), prosodic marking becomes superfluous.

The analysis presented in this paper leads to a novel theoretical interpretation of focus marking. An F-marked phrase does not automatically lead to prosodic prominence. The two strategies of focus association in Japanese why-questions do not differ in terms of the context in which the question is felicitously asked. Thus, the semantic status of a focus associate in a why-question must be the same in both strategies. Their prosodic realization differs, however, and we argue that it is due to the necessity of prosodic marking: one receives prosodic prominence because it is needed to be identified as the focus associate, and the other does not because the disambiguation process in syntax makes prosodic marking superfluous. In other words, the phonological interpretation of the same feature (focus) is influenced by the practical consideration of usefulness. We are still in search of an effective theory to characterize this generalization. Particularly important is the over-riding effect of sentence focus. Even if syntactic structure unambiguously identifies which phrase is the sentence focus, prosodic prominence on it cannot be eliminated. Such a situation may be better handled by a constraint-based analysis, but regrettably we will have to set it aside for future research.

Notes

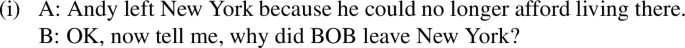

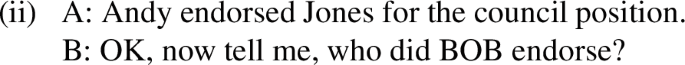

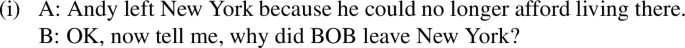

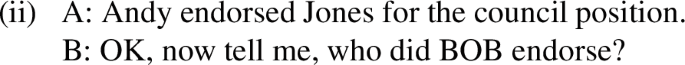

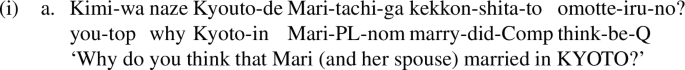

There is another kind of focalization effect, which is exemplified in (i).

Examples like (i) should be kept apart from the effects in (1). A case like (i) is more accurately described as an instance of contrastive topic, which can be analyzed as a wide-scope focus which out-scopes a question (cf. Constant 2014; Wagner 2012; Tomioka 2010a; b), which results in the meaning paraphrasable asFootnote 1 continued ‘as for BOB, why did he leave New York?’ Unlike (1), this type of focalization strategy is not limited to why-questions.

It is also worth noting that in the Japanese translations of these questions, the focalized phrases are marked with the topic marker wa, as noted in Tomioka (2010a). On the other hand, focus associates of why-questions in Japanese are never wa–marked, which indicates that the phenomenon exemplified in (1) is not a contrastive topic.

In all the Japanese examples in the paper, the focus associates are lexically accented words, and their focus prominence, when it is present, is indicated by the capitalization of the words.

Kawamura (2007) argues that the adjacency relation between why and its focus associate in the cleft construction is a consequence of constituency between the two phrases. Kawamura’s argument will be closely examined in Sect. 4, and for the time being we will stay descriptive and continue to refer to it as the adjacency effect.

(17) may be felicitous under the interpretation that the speaker is interested in knowing why John bought beer but not in why Andy did. However, such an interpretation is a contrastive-topic reading of the focus prominence, as briefly discussed in footnote 1.

The repeated/reinforced question after an elliptical question is not limited to why. For instance, the following conversation is natural and easily imaginable: ‘I saw Wes Anderson’s new movie.’ ‘When? When did you see it?’ Such a sequence is also possible in Japanese.

All the native speakers I consulted choose to place prominence on the same focused phrase as in the antecedent, but some wonder whether the second occurrence receives slightly reduced prominence compared to the first occurrence. The same issue may arise in Japanese. One reviewer reports that under some circumstances, prosodic marking becomes unnecessary even with focus-at-distance cases like (4), and I admit that there may be some speakers who can maximize the contextual cues to obtain the intended effects without assigning strong prominence to the focused phrases.

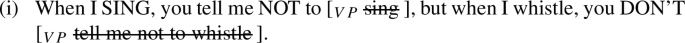

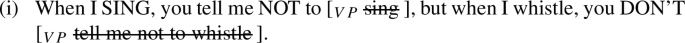

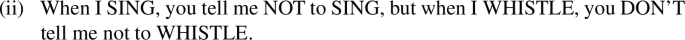

The pattern observed in (23) is reminiscent of a case of ‘sloppy’ ellipsis discussed in Schwarz (2000, Chapter 4). The elided VP in the second conjunct in (i) contains another smaller elided VP which yields the sloppy interpretation.

Schwarz (2000) observes that when the elided VPs are pronounced, the smaller VPs ([\(_{VP}\) sing ] and [\(_{VP}\) whistle ] ) receive prosodic prominence that is indicative of the presence of focus.

Presently we are not certain whether and how the two phenomena are related.

With the hypothesis that the focus sensitivity of why is due to \({exh}_{F}\), a new question arises: why is it not possible to have \({exh}_{F}\) in other constituent questions? We will address this question in the Appendix to this paper.

Since I will later adopt a movement theory of focus association, the semantic type of the exhaustive operator will be different from the sentential operator version of it. See Section 3.1 below.

Kawamura (2007) proposes a different analysis of the exhaustivity based on the event-semantic partition inspired by Herburger (2000). Her account treats why itself as a focus sensitive expression, but the discussion of fragmental why-questions earlier in this section has revealed that such an analysis is inconsistent with the generalization concerning focus-containing ellipsis. Kawamura’s solution also requires some mechanical tools which are not independently motivated. On the other hand, an account based on exhaustivity associated with focus is consistent with the generalization of focus-containing ellipsis and requires no ad hoc machinery.

There are a couple of issues that arise with the proposal. First, what happens if a causal wh-phrase undergoes movement? Does \({exh_{F}}\) move along with it? The assumption here is that the two elements are always local to each other both at Spell Out and LF. Thus, if why moves, \({exh_{F}}\) should also dislocate to stay close to why. However, it is not clear at this point whether various possible positions of why are created by movement or are the consequences of the relative freedom of the locations where why can be generated. See Rizzi (2001) and Ko (2005) for relevant discussion. The second issue is whether a why question always comes with \({exh_{F}}\). The complement of why need not contain a focused constituent. With the sentence, ‘Why is the train late?’, the speaker is asking for the reason of the train’s delay, and this interpretation shows no focus sensitivities. Thus, either \({exh_{F}}\) is optional in a why-question or \({exh_{F}}\) is always present but chooses the negation of the prejacent of why as the default alternative when the prejacent has no focus. The obligatory presence of \({exh_{F}}\) becomes a trickier issue, however, if it is not a sentential operator, as discussed in the next subsection. I will leave the optionality of \({exh_{F}}\) as an open question.

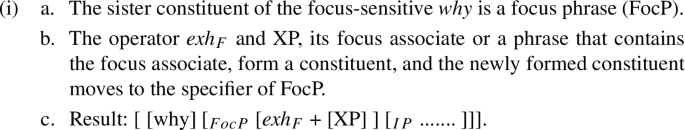

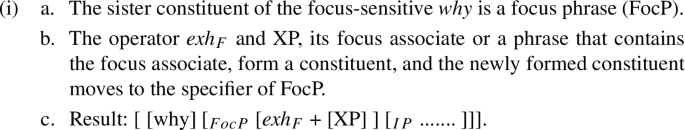

There remains a question of how the proximity of why and the focus exhaustivity operator \({exh_{F}}\) is accounted for. One possible way to capture the locality effect is summarized in (i).

One reviewer wonders whether why and \({exh_{F}}\) can ever be separated; in particular, whether it is possible to generate a structure in which why is located at the matrix level but \({exh_{F}}\) is confined within an embedded clause. This is an intriguing question that we nonetheless are unprepared to address properly.

We ignore the difference in the surface positions of the topic-marked Anna.

An anonymous reviewer asked whether the movement to \({exh_{F}}\) is not just island-sensitive but more restricted in a way that is reminiscent of QR – whether it is clause-bound. The following example, similar to the one presented by the reviewer, suggests that a long distance movement is possible.

The ambiguity is structural: naze Kyouto-de can be either inside or outside of the embedded clause. The sentence is indeed ambiguous (although the matrix reading is easier to obtain if the matrix verb is changed to omou-no ‘think-Q’ without the progressive marker). This indicates that a focused phrase can move out of an embedded clause to \({exh_{F}}\) in the matrix clause. It is consistent with the fact that the cleft formation can be long-distance. The reviewer further asks whether this ambiguity has impact on the prosody, in particular whether placing focus prominence on Kyouto-de can elicit one scope reading over the other. The current proposal makes no prediction in this regard, and the empirical facts are unclear, as we have obtained no firm judgments so far. I will leave this issue as an open question.

Incidentally, it is noteworthy that (47) does not require any prosodic marking on the focused phrase sono ronbun: it is indeed much more natural not to assign any prosodic prominence to it. It is consistent with the previous conclusion that prosodic marking is done only when there is a potential ambiguity in the location of focus.

To this example, the polite copula desu and the Q-marker ka are added. It is customary in the Japanese syntax literature that the sentence final no is regarded as the Q-marker. It should be pointed out, however, that this particle is homophonous with the finiteness marker. It is possible that its use as the Q-marker is derived from the structure no-desu-ka where the copula and the true Q-marker are unexpressed. The addition of desu-ka is to avoid the issue of the true identity of no.

Unlike the exhaustivity of a ‘free’ focus, the exhaustive meaning in the cleft construction is not conversational, as it is extremely hard to cancel it. While there seems to be a consensus that it is a conventional meaning, its exact nature is still being debated. See Büring and Kriz (2013) for an account that treats it as a presupposition.

An anonymous reviewer suggests that naze and the focus phrase may form a ‘surprising constituent’ in the sense of Takano (2002). While we admit that this possibility cannot be easily dismissed, the examination in the section shows that a constituency is not necessary to account for the pattern observed by Kawamura. Moreover, an analysis based on constituency would require that naze itself be a focus sensitive operator that uses the focus semantic value of the focused phrase, but, according to the data examined in Section 2, such an analysis is hard to justify.

Exactly how to account for the case marker drop is still being debated. In Hiraiwa and Ishihara (2012), the case-less version is considered an entirely different construction, which they call pseudo-cleft. This construction is a bi-clausal structure in which the presupposed clause is embedded under a nominal projection (DP) headed by no. This DP and the focused phrase in the pivot are in a predicational relation, and the material in the pivot is the focus that is exhaustively interpreted. The derivation of the case-less version of (45) is shown below.

I am grateful to Chris Tancredi, who pointed out this problem to me.

References

Baumann, Stefan. 2016. Second occurrence focus. In The oxford handbook of information structure, ed. Caroline Féry and Shinichiro Ishihara, 483–502. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Beaver, David I., Brady Clark, Edward Stanton Flemming, T. Florian Jaeger, and Maria Wolters. 2007. When semantics meets phonetics: Acoustical studies of second-occurrence focus. Language 83 (2): 245–276.

Beck, Sigrid. 2006. Intervention effects follow from focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 14: 1–56.

Bocci, Giuliano, Luigi Rizzi, and Mamoru Saito. 2018. On the incompatibility of Wh and focus. GENGO KENKYU (Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan) 154: 29–51.

Bromberger, Sylvain. 1992. On what we know we don’t know: Explanation, theory, linguistics, and how questions shape them. USA: University of Chicago Press.

Büring, Daniel. 2015. A theory of second occurrence focus. Language, Cognition and Neuroscience 30 (1–2): 73–87.

Büring, Daniel, and Manuel Kriz. 2013. It’s that, and that’s it! Exhaustivity and homogeneity presuppositions in clefts (and definites). Semantics and Pragmatics 6: 1–29.

Chierchia, Gennaro, Danny Fox, and Benjamin Spector. 2012. The grammatical view of scalar implicatures and the relationship between semantics and pragmatics. In Semantics: An International Handbook of Natural Language Meaning, de Gruyter, ed. Klaus von Heusinger, Claudia Maienborn, and Paul Portner. Manuscript: Harvard University & MIT.

Constant, Noah. 2014. Contrastive topic: Meanings and realizations. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Drubig, Hans Bernhard. 1994. Island constraints and the syntactic nature of focus and association with focus. Universitäten Stuttgart und Tübingen in Kooperation mit der IBM Deutschland GmbH.

Erlewine, Michael Yoshitaka. 2014. Movement out of focus. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Erlewine, Michael Yoshitaka, and Hadas Kotek. 2018. Focus association by movement: Evidence from tanglewood. Linguistic Inquiry 49 (3): 441–463.

Féry, Caroline, and Shinichiro Ishihara. 2010. How focus and givenness shape prosody. In Information structure: Theoretical, typological, and experimental perspectives, ed. Malte Zimmermann and Caroline Féry, 36–63. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fox, Danny. 2007. Free choice and the theory of scalar implicatures. In Presupposition and implicature in compositional semantics, ed. Uli Sauerland and Penka Stateva, 71–120. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Han, Chung-hye, and Maribel Romero. 2004. Disjunction, focus, and scope. Linguistic Inquiry 35 (2): 179–217.

Herburger, Elena. 2000. What counts: Focus and quantification. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Hiraiwa, Ken, and Shinichiro Ishihara. 2012. Syntactic metamorphosis: Cleft, sluicing, and in-situ focus in Japanese. Syntax 15: 142–180.

Ishihara, Shinichiro. 2011. Japanese focus prosody revisited: Freeing focus from prosodic phrasing. Lingua 121: 1870–1889.

Jacobs, Joachim. 1991. Focus ambiguities. Journal of Semantics 8 (1–2): 1–36.

Kawamura, Tomoko. 2007. Some interactions of focus and focus sensitive elements. Ph.D. thesis, Stony Brook University, SUNY.

Ko, Heejeong. 2005. Syntax of why-in-situ: Merge into [Spec, CP] in the overt syntax. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 23: 867–916.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1991. The representation of focus. In Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research, ed. Arnim von Stechow and Dieter Wunderlich, 825–834. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Kratzer, Angelika, and Junko Shimoyama (2002), Indeterminate pronouns: The view from japanese. In Proceedings of the third tokyo conference on psycholinguistics, ed Yukio Otsu. Tokyo: Hituzi Syobo.

Krifka, Manfred. 1994. The semantics and pragmatics of weak and strong polarity items in assertions. In Semantics and Linguistic Theory 4: 195–219.

Krifka, Manfred. 2001. For a structured meaning account of questions and answers. Audiatur vox Sapientia. A Festschrift for Arnim von Stechow 52: 287–319.

Krifka, Manfred. 2001. Quantifying into question acts. Natural Language Semantics 9 (1): 1–40.

Krifka, Manfred. 2006. Association with focus phrases. The Architecture of Focus 82: 105.

Nagahara, Hiroyuki. 1994. Phonological Phrasing in Japanese. Ph.D. thesis, UCLA.

Nirit, Kadmon. 2001. Formal pragmatics. USA: Blackwell Publishers.

Pierrehumbert, Janet, and Mary Beckman. 1988. Japanese tone structure. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Poser, William. 1984. The phonetics and phonology of tone and intonation in Japanese. Ph.D. thesis, MI.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2001. On the position of “Int(errogative)’’ in the left periphery of the clause. In Current studies in Italian syntax, ed. G. Cinque and G. Salvi, 267–296. Siena: Ms. Università di Siena.

Rooth, Mats. 1985. Association with focus. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1: 117–121.

Schwarz, Bernhard. 2000. Topics in ellipsis. Ph.D. thesis, University of Massachusetts – Amherst.

Selkirk, Elizabeth O. 2006. Bengali intonation revisited: An optimality theoretic analysis in which FOCUS Stress prominence drives FOCUS phrasing. In Topic and focus: Cross-linguistic perspectives on meaning and intonation, ed Matthew Gordon Lee, Chungmin and Daniel Büring. 215–244. Dordrecht: Springer.

Shinya, Takahito. 1999. Eigo to nihongo ni okeru fookasu ni yoru daunsteppu no sosi to tyooon-undoo no tyoogoo [The blocking of Downstep by Focus and Articulatory Overlap in English and Japanese]. Proceedings of Sophia Linguistics Society 14: 35–51.

Takano, Yuji. 2002. Surprising constituents. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 11 (3): 243–301.

Tancredi, Christopher. 1990. Syntactic association with focus. In Proceedings from the first meeting of the Formal Linguistic Society of Mid-America, 289–303.

Tancredi, Christopher. 1992. Deletion, deaccenting, and presupposition. Ph.D. thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Tancredi, Christopher. 2004. Associative operators. GENGO KENKYU (Journal of the Linguistic Society of Japan) 125: 31–82.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2007. Intervention effects in focus: From a Japanese point of view. In ISIS Working Papers of the SFB 632, ed Shinichiro Ishihara, Potsdam University, vol. 9.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2009. Why questions, presuppositions, and intervention effects. Journal of East Asian Linguistics 18: 253–271.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2010a. Contrastive topics operate on speech acts. In Information structure from different perspectives, ed M. Zimmermann and F. Caroline, OUP. 753–773.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2010. A scope theory of contrastive topics. Iberia 2: 113–130.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2017. Focus–prosody mismatch in japanese why-questions. In Proceedings of WAFL 13, ed Tomoyuki Yoshida, Céleste Guillemot and Seunghun J. Lee, MITWPL, 269–279.

Tomioka, Satoshi. 2020. Exhaustivity of focus and anti-exhaustivity of contrastive topic. Theoretical Linguistics 46 (1–2): 123–132.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 1995. Phonological Phrases: Their relation to syntax, focus, and prominence. Ph.D. thesis, MIT.

Von Stechow, Arnim. 1982. Structured propositions. Arbeitspapiere des SFB 99 59, Universität Konstanz Konstanz, Germany.

Wagner, Michael. 2006. Association by movement: Evidence from NPI-licensing. Natural Language Semantics 14 (4): 297–324.

Wagner, Michael. 2012. Contrastive topics decomposed. Semantics & Pragmatics 5 (8): 1–54.

Wold, Dag E.. 1996. long distance selective binding: the case of focus. In Proceedings of SALT VI, ed Teresa Galloway and Justin Spence, Ithaca. 311–328. NY: CLC Publications.

Yoshida, Masaya, Chizuru Nakao, and Ivan Ortega-Santos. 2015. The syntax of why-stripping. Natural Language & Linguistic Theory 33 (1): 323–370.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank, first and foremost, the three anonymous reviewers who read the manuscript carefully and gave me a number of valuable comments and suggestions. This paper is a much revised and expanded version of Tomioka (2017). It was originally presented at the satellite workshop, Prosody, Syntax and Information Structure in Altaic, at the 13th Workshop in Altaic Formal Linguistics (WAFL 13), held at International Christian University in 2017. I would like to thank Yoshi Kitagawa, the co-organizer of the satellite workshop, for giving me a chance to begin this project. I had very useful and insightful discussions at the workshop with Yoshi Kitagawa and several other participants, most notably Chris Tancredi and Junko Ito. Special thanks to Amanda Payne for helping me prepare the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix: Exhaustivity in Wh-questions

The lack of exhaustive implicatures in constituent questions is discussed in Tomioka (2020).

Appendix: Exhaustivity in Wh-questions

One of the key factors in the proposed analysis in the paper is that a focused phrase in a why-question is associated with the exhaustivity operator (\({exh_{F}}\)), rather than why itself. The fact that other constituent questions are not focus sensitive means that they cannot host \(\textit{exh}_{F}\), and one naturally wonders why that is so. This appendix addresses this issue, but we can offer only a preliminary analysis.

In many information-structure-based analyses of wh-questions (e.g., Krifka 2001a), wh-phrases themselves are regarded as foci, and the question of whether there are additional (non-wh) foci in constituent questions is a non-trivial matter. On the one hand, it has been observed that a (non-why) wh-phrase and a focus cannot co-occur in some languages. Italian is a well-known case (cf. Rizzi 1997; 2001). In connection with intervention effects in wh-questions, Tomioka (2007) claims that a (non-wh) focus in a wh-question is illegitimate in Japanese, regardless of their surface positions, and Bocci et al. 2018 offer an analysis that unites Italian and Japanese in this regard. On the other hand, English wh-questions can seem to host additional focused items, as in (2), repeated as (56).

While some have argued for the possibility of a non-wh focus in a constituent question (e.g., von Stechow 1982; Kadmon 2001), the focused phrases in (56) are realized as contrastive topics in the translations into languages in which contrastive topics are easily distinguished from foci (with Japanese being one such language). Whether non-wh foci in constituent questions are unambiguously contrastive topics or not, one fact is clear: focused phrases in constituent questions cannot be interpreted exhaustively. For instance, the question, who did ANNA meet on Friday? with focal prominence on ANNA, cannot mean ‘which person x is such that it is Anna that met x on Friday?’. If this interpretation were available, the following conversation would be well-formed.

C’s utterance was meant to correct the exhaustivity associated with ANNA, but its infelicity indicates that exhaustivity is absent in A’s question.

This in turn means that the following structure is not permitted:

We propose the following descriptive constraint to block (58):

(48) can differentiate why-questions from other wh-questions. It has been suggested (e.g., Rizzi 2001; Ko 2005) that why is merged directly into the specifier of CP without leaving any trace within the TP. For instance, the two sentences in (1) have the following LF representation, in which \({exh_{F}}\) is attached to the TP that contains no wh-traces.

As for the source of the constraint in (48), we speculate that it is based on interpretability. Suppose that all wh-phrases have Hamblin-style denotations and are moreover interpreted in situ (via LF reconstruction or the deletion of the higher copy in the Copy-and-Delete theory of movement). There are at least two compositional mechanisms to implement the Hamblin semantics.

Whichever mechanism is chosen, the exhaustivity operator \({exh_{F}}\) cannot perform its duty: it is a sentential operator whose prejacent is a proposition. Its contribution to the meaning is to exclude non-weaker alternatives to its prejacent. If we adopt (61a), then, a wh-containing TP denotes a set of propositions, rather than a proposition. Thus, the exhaustification is undefined. The other choice also fails to work for \({exh_{F}}\). If \({exh_{F}}\) is attached to a constituent containing a wh-phrase but not the relevant Q-morpheme, the ordinary semantic value of that constituent is undefined. Since \({exh_{F}}\) negates all the non-weaker alternatives to the ordinary semantic value, the operation cannot be performed if the ordinary semantic value is undefined.

While the proposal explains the lack of focus-related exhaustivity in non-why constituent questions, it crucially relies on the assumption that all wh-phrases reconstruct and are interpreted in their original positions. It remains to be seen if this assumption is independently justified.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tomioka, S. Focus without pitch boost: focus sensitivity in Japanese why-questions and its theoretical implications. J East Asian Linguist 31, 73–98 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-022-09235-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10831-022-09235-5