Abstract

In low-nutrient environments with few vascular plant symbiotic N fixers, biocrusts play an important role in ecosystem N cycling. A large number of studies across a wide range of biomes clearly confirm that not only the presence of biocrusts but biocrust community composition strongly influences N-fixation activity, with N fixation increasing with level of development (cyanobacterial-lichen biocrusts > dark cyanobacterial biocrust (e.g., Nostoc spp. and Collema spp.) > light Microcoleus-dominated biocrust). Nitrogen fixation by biocrusts results in N release to the soil in a variety of N forms (inorganic and organic N), thus elevating soil inorganic N pools in the top few millimeters of soil. The influence of N release on the bulk soil at greater soil depths is less clear, with biocrusts either elevating or having no influence on bulk soil inorganic N pools. The fate of N fixed and released by biocrusts, and whether this N is retained in the ecosystem in either soils or plants, determines ecosystem N balance over longer time scales, and results on the influence of biocrusts are mixed. Whereas we have multiple studies that examine a single compartment of N budgets, we lack studies that simultaneously address N inputs, losses, and soil and plant pools, thus precluding the construction of definitive N balances. One of the most consistent impact biocrusts have on ecosystem N is reducing N loss via wind and water erosion, with such losses consistently decreasing with increasing biocrust development.

Access provided by Autonomous University of Puebla. Download chapter PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

- Nitric oxideNitric Oxide

- Soil Organic Carbon

- Anaerobic Ammonium Oxidation

- Denitrification Rate

- Biological Soil Crust

These keywords were added by machine and not by the authors. This process is experimental and the keywords may be updated as the learning algorithm improves.

1 Introduction to Nitrogen Cycling in Biocrusts

Biocrusts play a significant role in the nitrogen (N) cycle within arid and semiarid ecosystems, as they contribute major N inputs via biological fixation and dust capture, harbor intense internal N transformation processes, and direct N losses via dissolved, gaseous, and erosional loss processes (Fig. 14.1). Because soil N availability in arid and semiarid ecosystems is generally low and may limit net primary production (NPP; Hooper and Johnson 1999), especially during periods when adequate water is available, understanding the mechanisms and controls of N input and loss pathways in biocrusts is critically important not only to our broader understanding of N cycling in dryland environments but also of overall dryland fertility. In particular, N cycling by biocrusts likely regulates short-term soil N availability to support vascular plant growth, as well as long-term N accumulation and maintenance of soil fertility.

Nitrogen (N) cycling in dryland areas. Nitrogen inputs into biocrusts are by means of N fixation and deposition. Within the biocrusts, N can be internally transferred by wind and water, and it can be metabolically transformed to then be present as ammonium (NH4 +), nitrate (NO3 −), organic N, and elemental N2. Nitrogen is lost by biocrusts by means of wind and water, leaching into deeper strata, and gaseous losses (e.g., NH3, NO, N2O, HONO)

In this chapter, we review the influence of biocrust nitrogen inputs, internal cycling, and loss pathways across a range of biomes. We examine linkages between N-fixation capabilities of biocrust organisms and spatiotemporal patterns of soil N availability that may influence the longer-term productivity of dryland ecosystems. Lastly, biocrust influence on N loss pathways such as N gas emissions, leakage of N compounds from biocrusts, and transfer in wind and water erosion are important to understand the maintenance of dryland soil fertility over longer time scales. Although great strides have been made in understanding the influence of biocrusts on ecosystem N cycling, there remain important knowledge gaps in our understanding of the influence of biocrusts on ecosystem N cycling that should be the focus of future studies. Because work on the interaction of N cycling and biocrusts up to 2001 was reviewed in Belnap and Lange (2003), this chapter will provide a brief summary of our current knowledge at the beginning of each section and then go on to focus primarily on research findings that have emerged over the last 14 years (2001–2015).

2 Biocrust Nitrogen Fixation

Biological fixation of atmospheric N2 (diazotrophy) is an ubiquitous biogeochemical transformation in biocrusts, and it likely constitutes a dominant source of N in dryland environments (Evans and Ehleringer 1993; Evans and Lange 2003). Multiple studies over years have addressed the environmental controls on N fixation rates and suggest that many factors can be at play [for a summary of the literature up to 2001, see Belnap (2003)]. Studies prior to 2001 showed that the environmental controls on N fixation are generally hierarchical: As biocrust organisms are physiologically active only when wet, moisture is a prerequisite and the first-order control on N fixation. Given sufficient hydration, energy and reduction equivalents are the main metabolic requirements for N fixation. Photochemical processes carried out by nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria, which are the dominant N fixers in biocrusts, are the ultimate source of this energy required for N fixation. Hence, light intensity can be a prime driver of diazotrophy. Temperature is an important determinant of chemical and biochemical reaction rates, and this applies to N fixation as well. Seasonality, as a compound succession of varying factors such as temperature, light, and moisture, thus drives the major dynamics of N fixation in biocrusts (Bowker et al. 2002; Belnap 2003). Beyond these parameters, antecedent conditions also influence N-fixation rates, as they can determine legacy amounts of reductants, nitrogenase enzyme, and N present in the biocrusts and surrounding soils.

For this chapter, we examined studies post-2001 to explore whether new insights have been gained since the Belnap (2003) review. Because many studies did not report all potentially relevant variables, we restricted our analysis to those studies reporting temperature, season of collection, biome, and biocrust type. In addition, studies using 15N2, unless 15N and acetylene incubations were done simultaneously, are not comparable to those using the acetylene reduction assay (ARA) (see discussion below), and thus we separated our analysis for these two methods. Natural 15N abundance cannot be used to quantify N inputs in most unmanaged ecosystems but can be used to indicate whether or not N fixation may be occurring and is discussed separately as well.

2.1 Studies Measuring Nitrogen Fixation Using the ARA Method

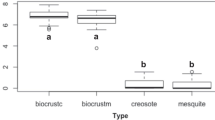

We found 21 publications using ARA under both laboratory and field conditions. Almost all studies in the set used the narrow temperature range of 24–26 °C, so we cannot expect to find useful information on the temperature effects on N fixation. Biocrust type, however, was a significant factor (Fig. 14.2). Light cyanobacterial biocrusts (dominated by low biomass Microcoleus spp., which are typically less mature) showed the lowest areal rates (~0.6 nmols C2H4 cm−2 h−1). Recent evidence suggests that N fixation in these light cyanobacterial biocrusts is associated with heterotrophic diazotrophic bacteria in the Clostridiaceae and Proteobacteria groups (Pepe-Ranney et al. 2015). Moss biocrusts and dark cyanobacterial biocrusts, dominated by a mix of Nostoc spp., Tolypothrix spp., Scytonema spp., as well as Microcoleus spp., showed an average of ~3–4 times higher rates than light biocrusts, whereas the cyanolichen Collema spp. and surface-dwelling sheets of Nostoc commune had the highest values of all (Fig. 14.2; ~10–11 nmols−1 C2H4 cm−2 h−1, respectively). These patterns are consistent with those reported by Belnap (2003) for studies prior to 2001.

Nitrogen fixation as measured by acetylene reduction assays (ARA) for different biocrust types. Values are means ± 1 SE. Different lowercase letters above each bar indicate statistical significance at the level of P < 0.05. ARA values were obtained from these publications: Aranibar et al. (2003), Barger (2003), Barger et al. (2013), Belnap (2002a, b), Billings et al. (2003), Caputa et al. (2013), Dickson (2000), Housman et al. (2006), Issa et al. (2001), Liu et al. (2009, 2012), Stewart et al. (2011a, b, c, 2012), Strauss et al. (2012), Su et al. (2011 b), Wu et al. (2009), Zhao et al. (2010), and Zielke et al. (2002)

ARA rates across different biomes (i.e., cold, cool, and hot desert) and season of collection (i.e., spring, summer, winter, fall) were highly variable and suggest that seasonality within a biome may have complex and interactive effects on N fixation. For example, Housman et al. (2006) showed that ARA rates peak during cooler, wetter time periods, which varied by biome type (Fig. 14.3). Spring ARA rates were highest in a North American cool desert site, whereas in a North American hot desert site, ARA rates peaked in the fall and winter (Fig. 14.3).

Nitrogen-fixation estimates from acetylene reduction assays in a cool (Colorado Plateau) and hot desert (Chihuahuan Desert) in North America. The figure was modified from Housman et al. (2006)

The high variability in ARA rates reported in the literature may at least partly reflect methodological limitations of the assay. ARA is based on the fact that the enzyme nitrogenase, which is normally responsible for catalyzing the reduction of N2 to NH3, can also reduce acetylene to ethylene, the latter reaction being an indirect measure of nitrogenase activity. Optimally, ethylene formation rates are then converted into actual rates of N fixation. The theoretical conversion ratio of ethylene to N2 fixed is between 3 and 4, depending on whether the H2 by-product produced during N fixation is driven by a unidirectional (uptake) hydrogenase [as discussed in Liengen (1999a) and Staal et al. (2001)]. All N-fixing cyanobacteria known contain uptake hydrogenases (Kothari et al. 2012). In a series of early experiments, Hardy et al. (1968) confirmed that this theoretical ratio ranged between 3 and 4 for bacterial cultures and legumes under laboratory and field conditions. Since this time, however, actual results from field and laboratory studies of biocrusts report that conversion ratios can range from 0.022 to 3.49 (Liengen 1999a; Stewart et al. 2011a; Caputa et al. 2013). Deviation (usually downwards) from the 3–4:1 ratio can result from several factors and may include the following: (1) suppressed reduction of H+ to H2 in the presence of acetylene leading to higher conversion ratios of acetylene to N2 (Jensen and Cox 1983); (2) acetylene is more soluble in water than N2 thus making acetylene more available to nitrogenase than N2 (Rice and Paul 1971; Nohrstedt 1983); (3) vanadium-based nitrogenase has lower ratios than molybdenum-based nitrogenase and some organisms can have either (Smith et al. 1987); (4) C2H2 can be toxic to microbes (David and Fay 1977); (5) acetylene can be adsorbed onto soil colloids (Rennie et al. 1978); and (6) differential diffusion barriers exist for acetylene. Because N2 or 15N2 only needs to diffuse into the soil, whereas ARA measures require gases to move both in and out of the soil before detection, the effect of these barriers to diffusion is more pronounced with ARA. Therefore, if the intent of a study is to establish absolute rates of fixed N by biocrusts, either ARA determined rates require calibration with 15N2 during the ARA measurements or 15N2 should be used instead. We note here that any underestimations of rates due to the effect of diffusion limitation will still exist for externally supplied 15N2.

15N2 Method

We could only find three studies since 2001 (Holst et al. 2009; Stewart et al. 2011a; Caputa et al. 2013) and two studies prior to that time (Mayland and McIntosh 1966; Liengen 1999b) that used 15N2 to measure N fixation in biocrusts. These studies were not focused on how environmental factors influenced N-fixation rates, as analysis was done under standard temperatures, moisture, and light and with materials collected in the same season. This is unfortunate, as the use of 15N2 is required for accurate comparisons among environmental variables and biocrust types. However, these studies do provide data on the appropriate conversion ratio for ARA under those experimental conditions, as all but Mayland and McIntosh (1966) analyzed samples both with ARA and 15N2. The most important finding is that ARA can underestimate N-fixation rates in biocrusts, as most studies found conversion ratios to be well below 3–4.

2.2 Natural 15N Abundance

Natural 15N abundance can be used to determine the overall balance of N inputs and losses or mass balance in those soils, with δ15N values (i.e., ratio of stable isotopes 15N:14N) close to zero indicating that fixed atmospheric N is likely a dominant source of N available for soils and organisms (Shearer and Kohl 1988). Several studies have used this method to assess if biocrusts are fixing atmospheric N (Aranibar et al. 2003; Billings et al. 2003; Russow et al. 2005; Marsh et al. 2006; Stewart et al. 2011a). In general, these studies show that soils overlain with biocrusts have lower 15N values than those without biocrusts, consistent with the notion that biocrusts do contribute fixed N to underlying soils and in agreement with global studies prior to 2001 (Evans and Lange 2003). Interestingly, Russow et al. (2005) compared biocrusts dominated by a non-N-fixing lichen to those dominated by Collema, showing that Collema was responsible for 88 % of the N in biocrusts.

2.3 Estimates of Annual Biocrust N Fixation

Similar to the wide range of ARA rates reported above, estimates of annual N inputs from biocrust N fixation are highly variable, ranging from 0.7 to 100 kg N ha−1 a−1 [reviewed by Evans and Lange (2003), Belnap (2002a, b), Russow et al. (2005), Stewart et al. (2011a, b, c), and Caputa et al. (2013)]. Quantification of N fixation by desert biocrusts globally reported an average N-fixation rate of 6 kg N ha−1 a−1 (Elbert et al. 2012).

The potential sources of error in scaling estimates of short-term N-fixation studies to an annual input are (1) inaccurate estimates of the duration of N-fixing activity in biocrusts, either daily or seasonally, (2) the lack of representativeness of the samples analyzed at the landscape level, and (3) the use of inaccurate ARA conversion ratios. As biocrusts are only active when wet, using continuously logged soil moisture data, the potential number of N-fixation activity days may be calculated. Metabolic activity, and thus the ability to fix N, is limited to ~10–12 % of the year in the Namib Desert, Germany temperate steppe, Colorado Plateau Desert, and South African Succulent Karoo (Lange et al. 1991; Lange and Green 2003; Darrouzet-Nardi et al. in press; Weber, unpublished). Thus, constraining the daily periods that biocrusts are physiologically active is critically important to estimating N inputs on an annual time scale. Newly developed biocrust moisture probes, to assess both the activity and the water content of biocrusts, may be a good resource for this (Weber et al. 2015a).

In addition to N fixation, N inputs from the atmosphere through both wet and dry deposition (~2 kg N ha−1 a−1 in relatively pristine air sheds up to 15 kg N ha−1 a−1 in impacted air sheds) may contribute to N inputs and N cycling dynamics within biocrusts. In fact, in air sheds highly impacted by N deposition, this additional source of N may relieve biological N limitation altogether. In a recent study, biocrusts collected from the pristine lower Sonoran desert and then transferred to the high-N atmosphere of the city of Tempe, Arizona, resulted in a complete loss of N-fixation capacity within weeks (Vaugh and Garcia-Pichel, unpublished).

The choice of ARA to N-fixation conversion ratios in estimates of N fixed is also an issue, as this may result in estimates of annual N inputs differing by an order of magnitude (Liengen 1999b; Caputa et al. 2013). Notably, however, upper estimates of annual N fixation are of similar magnitude as those of annual N fertilization inputs to agricultural systems [reviewed in Evans and Lange (2003) and Caputa et al. 2013). Clearly then, in the absence of significant N uptake by surrounding vascular plants, there should be evidence of significant system losses in N to offset estimates of high N inputs in order to explain the lack of longer-term soil N accumulation. This is discussed in the following sections.

3 Nitrogen Release to the Surrounding Substrate

Extracellular release of nitrogenous compounds, including inorganic forms such as nitrate [NO3 −] and ammonium [NH4 +], and small amounts of amide, peptides, and free amino acids , occurs in both cyanobacteria and lichens (Stewart 1970; Millbank 1982). Nitrogen release is especially pronounced in the presence of N-fixing organisms, which can release 5–70 % of N fixed (Magee and Burris 1954; Silvester et al. 1996). Kershaw (1985) reported that 19–28 % of labeled N applied to lichens was later found in surrounding soils. Earlier studies showed more N release when pH, temperature, light, CO2, or ionic conditions were suboptimal or during wetting after desiccation (Henriksson 1957; Jones and Stewart 1969a; Millbank 1982; Jeanfils and Rack 1992). Nitrogen release may occur very quickly once biocrust organisms become physiologically active. In Collema spp., NO3 − was released within 30 min of wetting (Garcia-Pichel and Belnap 2003). A recent study showed that a broad range of nitrogen-containing metabolites are continuously released and reabsorbed by biocrust-forming cyanobacteria such as Microcoleus vaginatus, a novel process not found across a broad range of other cyanobacteria (Baran et al. 2015). Rainfall patterns seem to affect this release: More NO3 − was released from dry biocrusts that received a saturating rain event, whereas more NH4 + was released from wet biocrusts that received a saturating rain event (Barr 1999). Williams and Eldridge (2011) observed that sand deposition had a strong effect on the release and thus bioavailability of nitrogen (N) after a severe drought. They observed that cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts covered by sand had up to three times more mineral N (ammonium and nitrate) and twice the mineralizable N than sand-free biocrust samples, likely resulting from autolysis and the subsequent breakdown of cyanobacterial cells rich in N. The compounds released can be readily taken up by surrounding organisms, including reuptake by the organisms or associated vascular plants, fungi, actinomycetes, and/or bacteria (Stewart 1967; Jones and Stewart 1969a, b; Rogers and Burns 1994). This in fact contributes largely to a nice differentiation among allopatric bacteria in biocrust systems (Baran et al. 2015). In the case of NH4 +, release from nitrogen-fixing organisms supports very intense rates of nitrification in all biocrusts analyzed (Johnson et al. 2005; Strauss et al. 2012) and significant standing stocks of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria (Marusenko et al. 2013).

4 Biocrust Influence on Soil Inorganic Nitrogen

Nitrogen fixed by diazotrophic organisms not only contributes to the fertility of soils with inherently low nutrient availability but may be an important nutrient source for diverse groups of organisms such as neighboring vascular plants (see Chap. 19 by Zhang et al.), fungi and bacteria (see Chap. 5 by Maier et al.), and mosses (see Chap. 6 by Seppelt et al.). Although N release from biocrust organisms has been well documented across a range of biomes and biocrust types (see Sect. 14.3), results are mixed as to whether this release appreciably enhances inorganic (NO3 − and NH4 +) bulk soil N.

The positive influence of biocrusts on inorganic N has been clearly demonstrated within biocrusts at the soil surface (0–2 mm; Fig. 14.4, Johnson et al. 2007). In both light cyanobacterial- and moss-/lichen-dominated biocrusts, inorganic N in pore water was six- to tenfold higher at 1 mm below the soil surface compared to 10-mm depth (Fig. 14.4). The peak inorganic N values were coupled with high O2 saturation, suggesting that this peak occurred in the zone of high photosynthetic activity. Biocrust N-fixation rates may also influence soil inorganic N levels. Higher amounts of inorganic N were collected on ion exchange resins from biocrust types with higher N-fixation rates (Collema tenax vs. Microcoleus biocrusts; Belnap, unpublished).

Vertical chemical profiles measured in the soil solution of wetted, active soil crusts using microsensors and obtained 3–6 h after initial wetting. Total ammonium (NH4 + + NH3) profiles demonstrate accumulation close to the surface. Nitrate profiles also indicate a zone of production 2–3 mm deep, coincident with the maximal activity of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Modified from Johnson et al. (2005)

The influence of biocrusts on inorganic N within the bulk soil (>10 mm depth) is mixed with studies showing higher (Guo et al. 2008; Delgado-Baquerizo et al. 2013), lower (Castillo-Monroy et al. 2010), or no difference (Castillo-Monroy et al. 2010) in biocrust inorganic N relative to bare soil. Sampling depth may partially explain these mixed results. The steep gradient in decreasing inorganic N from 0 to 10 mm [as shown in Johnson et al. (2007)] may suggest that the influence of biocrusts on inorganic N may be limited to the top few mm of soil and sampling at deeper soil depths would likely eliminate differences in inorganic N across biocrust types. For example, no differences in inorganic N were reported in the top 5 cm of soil underlying either light or dark cyanobacterial biocrusts on the Colorado Plateau (Barger et al. 2005). However, in a later study of biocrusts from the same sites, NH4 + was 40 % and NO3 − was 100 % higher in dark compared to light cyanobacterial biocrusts when sampling the top 2 cm of soil (Barger et al. 2013).

Although few studies have examined the transport of inorganic N from biocrusts at the surface to underlying soils, subsurface inorganic N (5–50 mm depth) was shown to be strongly and positively correlated with biocrust inorganic N at the soil surface (top 5 mm) (Guo et al. 2008). In the few studies on inorganic N transport from surface biocrusts to underlying soils, biocrust type does appear to be an important factor, but not in a predictable manner (Thiet et al. 2005; Veluci et al. 2006; Johnson et al. 2007). In a hot desert environment, no differences were observed in the downward transport of NH4 + in light vs. dark cyanobacterial biocrusts, whereas downward transport of NO3 − in light biocrusts was nearly three times higher than in dark biocrusts (Johnson et al. 2007). Veluci et al. (2006) showed the opposite pattern in which NH4 + leaching was higher, and NO3 − leaching lower, in lichen-covered as compared to moss-covered or bare soil in a more mesic environment. Although the patterns in inorganic N transport to underlying soil are not consistent and probably also depend on pH and soil characteristics, the magnitude of N transport may be significant. In temperate sand dune soils, inorganic N transport associated with biocrusts ranged from 0.02 to 0.8 g m−2 year−1, rates which are similar to N-fixation rates (Thiet et al. 2005).

5 Nitrogen Gas Losses from Biocrusts and Biocrusted Soils

Gaseous N loss constitutes a major pathway in which N fixed by biocrusts may subsequently be lost from the ecosystem, either directly from the biocrust itself or from export reservoirs. Thus, the magnitude of gaseous N emissions relative to N inputs via fixation will strongly govern N retained within the ecosystem and longer-term soil fertility. Enhanced NH4 + and NO3 − availability, within biocrusts (as described in Sect. 14.4), may promote N gas emissions through the biotically driven processes of nitrification (oxidation of NH4 + to NO3 −), denitrification (NO3 − reduction to nitrogen oxides with N2 as an endpoint), and abiotic losses via ammonia volatilization (NH4 + conversion to NH3 gas) as all of these processes have gaseous end products or intermediaries (Fig. 14.5). Over the past decade, significant advances have been made in measuring N gas emissions from biocrusted soils across a range of biocrust types and biomes (Table 14.1). More recent explorations of anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) rates suggests that while this process does occur, it most likely plays a negligible role in N transformation in biocrusts and is unlikely to contribute significantly to overall N gas emissions (Strauss et al. 2012; Abed et al. 2013). Less explored pathways of N gas loss associated with codenitrification (N gas production during which one N atom of nitrite or nitric oxide combines with one N atom of another N species, as, e.g., amino compound), nitrifier denitrification (NH3 oxidation to NO2 −and subsequent reduction of NO2 −to NO, N2O, or N2), and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium (DNRA) have gained increasing attention in soil ecology and may play a yet unexplored role in biocrust emissions (Wrage et al. 2001; Rütting et al. 2011; Spott and Stange 2011). Although N gas emissions from biocrusts have focused on biogenic processes, abiotic reactive N gas loss, as has been determined to exist in both biocrusted and bulk soils (McCalley and Sparks 2008), may also be a significant loss pathway.

Desert soils provide optimal conditions for ammonia (NH3) volatilization : Rates are often positively correlated with the generally high soil pH and total salt content found in desert soils, but negatively correlated with the often low organic matter content, cation exchange capacity (CEC), and clay content (Duan and Hongland 2000). Recent studies suggest that NH3 volatilization may be a major loss pathway for N relative to other reactive N gases in bulk desert soils (McCalley and Sparks 2008). Reported rates of NH3 volatilization from biocrusts vary widely, ranging from 1.4 to 336 μg N m−2 h−1 (Table 14.1). In Mojave Desert soils, biocrusts had no influence on NH3 emissions (McCalley and Sparks 2008). In contrast, in a laboratory incubation of sandy soil from the Colorado Plateau, NH3 emissions were threefold higher on biocrusted soils compared to soils where biocrusts were removed (Evans and Johansen 1999). Although data on NH3 emissions by biocrust type are limited, laboratory incubations of Colorado Plateau light and dark biocrusts emission rates were similar (Barger 2003). Similar to NO gas loss, NH3 loss was consistently observed in dry biocrust soils (McCalley and Sparks 2008, 2009). Estimates of annual NH3 from biocrusts in Mojave Desert soils were 1.4 kg N ha−1 a−1 (McCalley and Sparks 2008).

A suite of nitrogen oxides are produced biogenically as by-products of nitrification and denitrification processes (Fig. 14.4) and abiotically through chemical formation driven by high temperatures (McCalley and Sparks 2009). Nitric oxide (NO) and nitrous oxide (N2O) are the dominant by-products in nitrification and denitrification processes with soil water content as a primary control on emissions. Under low soil water conditions, intensive rates of nitrification favor production of NO (Weber et al. 2015b). In contrast, saturated soils and subsequent low O2 conditions favor denitrification processes and high N2O emissions (Firestone and Davidson 1989; Hartley and Schlesinger 2000; Pilegaard 2013).

Until recently, denitrification had been a relatively unexplored N loss pathway from biocrusted soils because conditions conducive to the process (e.g., anoxic soils and high levels of soil organic carbon (SOC) and soil NO3 −) were thought to be limited in dryland environments (Tucker and Westerman 1989). Denitrification is primarily a biological process, whereby denitrifiers (primarily heterotrophic bacteria) use NO3 − for respiration of organics in the absence of O2 resulting in the production of NO, N2O, and N2 (Fig. 14.4). The high rates of soil respiration prevalent immediately following a precipitation event, however, do deplete biocrust O2 concentrations, providing the anaerobic conditions required for denitrification. Thus, conditions conducive to denitrification do occur inside of biocrusts at the microscale, with anoxia brought about by respiration, NO3 − supplied locally by nitrification, and organic carbon in the pore water supplied by export from primary producers (see Johnson et al. 2007). Yet, denitrification rates are typically much lower than those of nitrification or N fixation for any given site and condition or assay (Johnson et al. 2007; Strauss et al. 2012).

Denitrification rates in biocrusts and underlying soils are temporally and spatially variable with estimates varying by five orders of magnitude (Table 14.1, 0.03–8181 μg N m−2 h−1). One must note, however, that much of this variability in Table 14.1 is driven by exceedingly high rates obtained from a single study conducted with a different technique (Abed et al. 2013). Although soil denitrification rates are consistently shown to be highly variable across a broad range of biomes and soil types, the wide range of analytical methods, environmental conditions in which soils were incubated, and differences in soil sampling depths across the studies may partially contribute to the variability in reported rates (Table 14.1).

Soil organic carbon (SOC) formed by biocrusts may increase denitrification rates (Barger et al. 2013; Brankatschk et al. 2013). In one study on a Central European duneland, denitrification on uncrusted sand was undetectable, whereas rates from three biocrust types ranged from 5 to 48 μg N m−2 h−1 (Brankatschk et al. 2013). An increase in SOC with biocrust development was hypothesized to be driving the higher rates. Additional studies have shown that biocrust development leads to higher denitrification rates (Strauss et al. 2012; Barger et al. 2013; Brankatschk et al. 2013), while other studies have shown the opposite (Abed et al. 2013; Zaady et al. 2013) or no effect (Johnson et al. 2007; Strauss et al. 2012; Zaady et al. 2013), perhaps not an unexpected result given the multiplicity of factors that can influence denitrification.

Simultaneous measurements of denitrification and N fixation reveal that biocrust N fixation generally exceeds denitrification. In both hot and cold desert biocrusts, denitrification rates ranged from 0.1 to 25 % of the N-fixation rates (Johnson et al. 2005; Strauss et al. 2012; Barger et al. 2013; Zaady et al. 2013). The exception to this pattern was a study conducted on an inland dune in Germany, whereby denitrification rates from biocrusts were five- to tenfold higher than N-fixation rates (Brankatschk et al. 2013). Biocrusts from this study experienced historically high levels of N deposition (12–15 kg ha−1 a−1), which may have contributed to the high denitrification rates (Brankatschk et al. 2013). In addition, N-fixation rates in all of these studies were likely underestimated due to the use of high ARA to N-fixed conversion ratios.

Few studies have attempted to estimate annual denitrification rates , but recent estimates from the Negev desert suggest that denitrification from biocrusted soils ranged from 7.2 to 10.8 kg ha−1 a−1. Biocrust N fixation at these same sites was estimated at 43.2 kg ha−1 a−1, which suggests that a quarter of the N fixed each year may be lost in denitrification (Zaady et al. 2013). It is important to note that many denitrification estimates are potential rates based on optimal conditions, where conditions of organic carbon supply, anoxia, and long incubation times are all experimentally imposed in the assays relative to the field environment. Thus, potential denitrification rates are likely overestimates and may represent an upper end to N loss.

Nitric oxide (NO) may be produced biogenically both during nitrification and denitrification processes and abiotically through chemical formation driven by solar radiation and moisture (McCalley and Sparks 2009). NO production occurs in both nitrification and denitrification processes with emission rates from 1.1 to 751 μg m−2 h−1 from biocrusts and biocrusted soils (Table 14.1). NO loss in dryland soils is positively correlated to nitrification rates (Hartley and Schlesinger 2000; Martin et al. 2003), suggesting that NO is primarily produced during nitrification. Similar to N fixation, soil moisture is a first-order control on NO emissions (Barger et al. 2005; McCalley and Sparks 2008, 2009). In contrast to previous reports of non-detectable levels of NO loss in dry biocrust soils (Barger et al. 2005), results from McCalley and Sparks (2008, 2009) revealed that low NO emissions occur in dry biocrusts. Biocrust NO emissions also increase with increasing temperature (Barger et al. 2005; McCalley and Sparks 2008, 2009). NO emissions from biocrusts in SE Utah were nearly fivefold higher in the hot summer months relative to the cooler spring and fall time periods (Barger et al. 2005). In summer months, when soil temperatures exceed 50 °C, higher NO fluxes may also be driven by abiotic processes (McCalley and Sparks 2009). Similar to what was the case with denitrification rates, the influence of biocrust type had mixed effects on NO emissions. In SE Utah, NO fluxes from dark cyanobacterial biocrusts were nearly double those of light cyanobacterial crusts, but only during the warmer summer months. In the Mojave Desert, NO fluxes were similar in light cyanobacterial biocrusted and uncrusted soils (McCalley and Sparks 2008). Emissions of biocrusts in the Succulent Karoo showed large variation depending on the type of biocrust with dark cyanobacteria-dominated biocrusts reaching mean maximum emission values of 751 μg m−2 h−1 of NO-N, whereas bare soil emitted a mean value of 33 μg m−2 h−1 (n = 4; Table 14.1; Weber et al. 2015b). Emission values obtained by biocrusts of typical composition during one wetting and drying cycle (0.74 ± 0.08 μg m−2 h−1 of NO-N) were combined with climate and biocrust composition data to obtain an annual global estimate of 1.1 Tg a−1 of NO-N emissions. Former estimates of annual NO gas loss from biocrusts were by far lower ranging from 0.10 to 0.16 kg N ha−1 a−1 (Barger et al. 2005; McCalley and Sparks 2008).

During both nitrification and denitrification nitrite (NO2 −) are formed, which, under suitable conditions, can be released to the atmosphere as HONO (nitrous acid ). Only recently HONO emissions have been reported from bulk soil (Su et al. 2011a) and soil bacteria (Oswald et al. 2013) and by biocrusts (Weber et al. 2015b). The presence of biocrusts results in higher HONO emissions, whereby all biocrust types released significant amounts of HONO in contrast to the very low emissions reported for bare uncrusted desert soils. As observed for NO, HONO emissions were strongly related to the soil water content. Based on long-term climate and biocrust composition data, global release of HONO-N was estimated at 0.6 Tg a−1. Summarizing the analyzed NO and HONO emissions, 1.7 Tg a−1 of reactive nitrogen were found to be emitted, corresponding to ~20 % of the global nitrogen oxide emissions of soils under natural vegetation (Ciais et al. 2013).

6 Regulation of Biocrust Nitrogen Transfer in Wind and Water

In dryland ecosystems, water runoff and wind - and waterborne sediment export from plant interspaces are long recognized pathways of N transfer (Ludwig et al. 1997; Ravi et al. 2011). Several studies show that biocrusts influence water and associated nutrient transfers from biocrusted interspace soils to downslope plants (Eldridge et al. 2000, 2002; Maestre et al. 2002). Whereas many studies have found elevated areal N under shrubs relative to interspace soils (e.g., Thompson et al. 2006), many others show no such differences where well-developed biocrusts cover interspace soils (e.g., Allington and Valone 2014). In none of these studies, however, was the role of biocrusts explicitly tested, and inferring transfer rates from standing stocks alone does not adequately describe the specific N transfer mechanisms.

Biocrust type can affect N transfer in overland flow. In a series of 30-min rainfall simulation experiments on sandy soils in SE Utah, sediment N loss was an order of magnitude higher in light cyanobacterial biocrusts (0.6 g m−2) than in the more stable, dark cyanobacterial biocrusts (0.06 g m−2), with over 98 % of the N flux coming from the sediment (Barger et al. 2006). Sediment and thus N loss was a negative function of biocrust biomass, as indicated by chlorophyll a content (R 2 = 0.82) (Fig. 14.6). In this one high-intensity rainfall simulation event, nearly 3 % of the estimated surface organic N was removed from light biocrusted soils compared to <1 % in dark cyanobacterial crusts. In a similar study on sandy soils in the Tengger Desert, total N flux in runoff and sediment transport from dark cyanobacteria-lichen-moss biocrusts was 0.42 g N m−2 (Li et al. 2008), similar to those reported above. Most of the N flux was transported from biocrust patches downslope, and 74 % of the sediment N and 45–73 % of the dissolved N were subsequently trapped by downslope vegetation (Li et al. 2008). Using silt fences to capture sediment released in natural runoff events from 40 m2 watersheds over a 4-month period, sites on sandy soils produced an average of 0.05 g N m−2 from dark cyanobacterial biocrusted soils, compared to an average of 56 g N m−2 from adjacent, recently disturbed uncrusted soils (J. Belnap, unpublished). On clay soils, the dark cyanobacterial biocrusted soils produced an average of 0.05 g N m−2 and the disturbed uncrusted soils an average of 0.66 g N m−2 over the same 4-month time period. In contrast to these patterns, higher runoff from biocrusted soils relative to bare soils in some settings can result in loss of water and nutrients at the watershed level (Yair et al. 2011).

Wind redistributes sediments in drylands, at the local (e.g., to nearby shrubs; Ravi et al. 2010) to regional (e.g., to nearby mountains; Neff et al. 2008) scale, and often moves more sediment than water does (Field et al. 2011). Biocrusts reduce sediment loss via wind erosion by up to 66 times compared to uncrusted surfaces (see Chap. 16 by Belnap and Büdel; Field et al. 2011). Because sediments contain N, biocrusts will therefore reduce N transfer by wind. However, we could find only one study quantifying this process (J. Belnap, unpublished). In SE Utah, sediment was collected by dust samplers (units expressed as the collection area of the sampler) from perennial and annual grasslands with varying crust types. Nitrogen lost from the grassland dominated by perennial native plants and dark cyanobacterial biocrusts was very low in all years (~0.1 mg N cm−2 a−1 to ~2 mg N cm−2 a−1 in a wet and dry year, respectively). In contrast, a nearby area on the same soil type but dominated by annual plants and light cyanobacterial biocrusts lost a similar amount of N in wet years (0.2–0.4 mg N cm−2 a−1) but much higher amounts in a drier year (~70 mg N cm−2 a−1). Areas with only annual plants and no biocrusts had very high N losses in both wet and dry years, losing up to 10 mg N cm−2 a−1 and ~160 mg N cm−2 a−1 in a wet and dry year, respectively. While this difference may not have been entirely due to the difference in biocrusts, as the plant type and/or cover also varied, wind erosion models show that dark cyanobacterial biocrusts completely stabilize soils, even when no plant cover is present (Munson et al. 2011). Wind and water also interact to move N in drylands (Belnap et al. 2011), but unfortunately the role of biocrusts in such coupled transfers of N has not been studied.

Nitrogen has also been reported to be moved from biocrusts to nearby plants, with the proposed agent being biocrust fungi (Green et al. 2008). Three studies showed that labeled N added to interspace biocrusts could be found within hours in plant tissue 1 m away. An expanded discussion on this topic is found in Chap. 19 by Zhang et al.

Nitrogen movement by wind and water erosion may result in both N loss from the system but also N transfer within the system. For example, estimates of N fixation by biological soil crusts on the Colorado Plateau ranged from 1.3 kg N ha−1 a−1 in light cyanobacterial biocrusts up to 9 kg N ha−1 a−1 in dark cyanolichen biocrusts (Belnap 2002a, b). In a high-intensity rainfall simulation event, N flux from light cyanobacterial biocrusts was 6.3 kg N ha−1 (sixfold higher than annual N inputs) as compared to only 0.6 kg N ha−1 lost from dark cyanobacterial biocrusts. Early successional light cyanobacterial biocrusts have low N-fixation potential, and N losses of this magnitude would require a significant number of years for recovery. Thus, a single high-intensity rainfall event may dramatically alter N balance within biocrusts.

7 Ecosystem Nitrogen Budgets

The very fact that nitrogen fixation is such a prominent and ubiquitous trait of biocrusts speaks clearly for a permanent state of N limitation and requires that much of the N fixed is exported away from the crust in some form or another. The fate of N fixed by biocrusts and whether this N is retained in the system or lost via the broad range of pathways (described in earlier sections) determines ecosystem N balance over longer time scales. Given that N-fixation estimates may be quite high but soil N accretion rates are generally low (10 % of N fixed, Peterjohn and Schlesinger 1990) suggests that either major errors in estimates or scaling of biocrust N fixation plague our current approaches as described in the previous section or annual N losses are several orders of magnitude higher than what would be anticipated in these relatively low-nutrient environments. Additionally important pools or processes may yet to be adequately considered and measured (e.g., N transfer to plants; see Chap. 19 by Zhang et al.). Although numerous studies of N losses and transfers from biocrusts have contributed to our understanding of the fate of N fixed by biocrusts over the past decade, significant uncertainties related to biocrust N balance still remain. Specifically, the challenges in measuring all pathways of N inputs, losses, and retention simultaneously under environmentally relevant field conditions have limited our ability to “close” the N cycle.

Over longer time scales, the balance between N inputs and losses is reflected in accumulation of soil organic N. A recent survey in North America showed that biocrusts accumulate very significant levels of total N (severalfold) above the background levels found in uncrusted, neighboring soils (Beraldi-Campesi et al. 2009). An example taken from a Central European duneland shows that soil organic N was similar across the top 35 mm of the soil surface in undeveloped, mobile sands (Fig. 14.7, Brankatschk et al. 2013). As cyanobacteria colonized soil surfaces, organic N increased in the zone of biocrust activity (0–5 mm). In later successional stages (algal-cyanobacteria-moss biocrust), soil organic N in these duneland ecosystems was more than ninefold higher than that of the mobile sands (Fig. 14.7). Soil N in subsurface soils was similar across all development stages and suggests that any N transfer from surface soils does not result in significant N accretion in subsurface soils.

Soil organic N accretion with biocrust development on a Central European inland dune. Mobile sand = bare substrate with no biocrust development; Phase 1 = sand grains that are stabilized at their contact zones by filamentous cyanobacteria and green algae; Phase 2 = cyanobacteria and green algae; Phase 3 = filamentous and coccoid green algae, some cyanobacteria, fungal hyphae, and mosses. Modified from Brankatschk et al. (2013)

A similar pattern of soil organic N accumulation in surface soils was observed across a range of biomes. In a review of seven studies, the presence of biocrusts consistently increased soil surface N relative to subsurface soils (Fig. 14.8). In cold and cool desert environments, the pattern of higher N in surface soils was much greater in dark biocrusts (cyanobacterial and cyanolichen) relative to light cyanobacterial biocrusts. Interestingly, this pattern was not consistent in hot desert environments. Soil N accretion in surface soils in a study in the Negev and the Sonoran Desert studies was lower in dark biocrusts relative to light biocrusts relative to subsurface soils (Fig. 14.8).

The influence of biocrust type on soil surface enrichment of soil organic N across biomes. “Dark” biocrusts included both dark cyanobacterial biocrusts and dark cyanolichen biocrusts. Numbers next to each site name on the x-axis denote the publication in this order: [1] (Barger 2003; Barger et al. 2013); [2] (Breen and Lévesque 2008); [3] (Brankatschk et al. 2013); [4] (Chamizo et al. 2012); [5] (Drahorad et al. 2013); [6] (Miralles et al. 2012); [7] (Strauss et al. 2012)

8 Summary of Biocrust N Cycling

In low-nutrient environments with few vascular plant symbiotic N fixers, biocrusts play an important role in ecosystem N cycling. A large number of studies across a wide range of biomes clearly confirm that not only the presence of biocrusts but biocrust community composition strongly influences N-fixation activity, with N fixation increasing with level of development (cyanobacterial-lichen biocrusts > dark cyanobacterial biocrust (e.g., Nostoc spp. and Collema spp. ) > light Microcoleus -dominated biocrust). Nitrogen fixation by biocrusts results in N release to the soil in a variety of N forms (inorganic and organic N), thus elevating soil inorganic N pools in the top few millimeters of soil. The influence of N release on the bulk soil at greater soil depths is less clear, with biocrusts either elevating or having no influence on bulk soil inorganic N pools. The fate of N fixed and released by biocrusts, and whether this N is retained in the ecosystem in either soils or plants, determines ecosystem N balance over longer time scales, and results on the influence of biocrusts are mixed. Whereas we have multiple studies that examine a single compartment of N budgets, we lack studies that simultaneously address N inputs, losses, and soil and plant pools, thus precluding the construction of definitive N balances. One of the most consistent impact biocrusts have on ecosystem N is reducing N loss via wind and water erosion, with such losses consistently decreasing with increasing biocrust development.

9 Research Challenges

-

1.

Biocrust N fixation—On a global scale, N fixation by biocrusts was estimated to account for ~ 26 Tg a−1 or half of the global N fixation as estimated in the latest IPCC report (Elbert et al. 2012; Ciais et al. 2013). Thus, well-constrained estimates of biocrust N fixation at larger spatial scales are important for our broader understanding of global N cycles. To better estimate biocrust N fixation across biocrust types and biomes, future biocrust N-fixation studies should (1) report antecedent conditions such as the amount of time biocrusts were metabolically active before measurements, (2) measure temperature within the biocrust rather than air, (3) use 15N2 or calibrate ARA with 15N2, and (4) increase incubation times to avoid diffusion limitation (Johnson et al. 2005).

-

2.

Spatiotemporal scaling of biocrust N cycling—Many of the studies described in this chapter examine biocrust N input and loss pathways on short time scales (i.e., minutes, hours) and small spatial scales (i.e., centimeters to meters). Although these detailed studies of biocrust N cycling have been critical to increasing our understanding of the important environmental controls on N transformations in biocrusts, temporally scaling short-term N loss rates to annual losses still remains a challenge due to the high spatial and temporal variability in rates.

-

3.

Soil moisture and temperature monitoring—Since biocrust organisms are physiologically active only when adequate water is available, continuous monitoring of moisture in soil lichens, mosses, and surface soils (0–0.5 cm or less) is important for constraining N budgets.

-

4.

Use of common methodologies and units—Future studies are encouraged to use common methodologies and units during reporting in order to compare across all aspects of biocrust N cycling, especially for N fixation. To facilitate future meta-analyses and reviews, N cycling rates should be reported on both a mass and area basis in the supplementary material for comparison across studies. Ancillary soil data such as soil texture, moisture, temperature, SOM, total N, and inorganic N pools are the most important measures for biocrust N cycling studies in addition to adequately characterizing the biocrust community with measures of chlorophyll a and biocrust species composition.

-

5.

Biocrust N release and uptake—Understand the environmental conditions that result in N release and subsequent uptake by soil microorganisms and surrounding plant communities and how these dynamics may change with anthropogenic atmospheric N deposition.

-

6.

Simultaneous measures of N inputs, losses, and all pools (soil and plant)—Examine covariation of integrated cycling (many processes) with fundamental environmental drivers (i.e., temperature, moisture). Studies focused solely on one type of transformation are by now of very limited value, in view of the large variability of each process in space and time.

-

7.

Understand the limits of denitrification in biocrusts—As reported in previous sections, conditions within active biocrusts are prime for denitrification (i.e., anoxic conditions, organic matter supplied by photosynthetic release, and nitrate supplied by strong nitrification), and yet rates are generally low (in many but not all studies) compared to the potentials.

References

Abed RMM, Lam P, de Beer D, Stief P (2013) High rates of denitrification and nitrous oxide emission in arid biological soil crusts from the Sultanate of Oman. ISME J 7:1862–1875

Allington GRH, Valone TJ (2014) Islands of fertility: a byproduct of grazing? Ecosystems 17:127–141. doi:10.1007/s10021-013-9711-y

Aranibar JN, Anderson IC, Ringrose S, Macko SA (2003) Importance of nitrogen fixation in soil crusts of southern African arid ecosystems: acetylene reduction and stable isotope studies. J Arid Environ 54:345–358

Austin AT, Yahdjian L, Stark JM, Belnap J, Porporato A, Norton U, Ravetta DA, Shaeffer SM (2004) Water pulses and biogeochemical cycles in arid and semiarid ecosystems. Oecologia 141:221–235

Baran R, Brodie EL, Mayberry-lewis J, Hummel E, Nunes U, Rocha D, Chakraborty R, Bowen BP, Karaoz U, Cadillo-quiroz H, Garcia-Pichel F, Northen TR (2015) Soil Bacteria. Nat Commun 6:1–9. doi:10.1038/ncomms9289

Barger NN (2003) Biogeochemical cycling and N dynamics of biological soil crusts in a semi-arid ecosystem. Ph.D. dissertation. Colorado State University, Fort Collins, CO, pp 131

Barger NN, Belnap J, Ojima DS, Mosier A (2005) NO gas loss from biologically crusted soils in canyonlands national park, Utah. Biogeochemistry 75:373–391

Barger NN, Herrick JE, Van Zee J, Belnap J (2006) Impacts of biological soil crust disturbance and composition on C and N loss from water erosion. Biogeochemistry 77:247–263. doi:10.1007/s10533-005-1424-7

Barger NN, Castle SC, Dean GN (2013) Denitrification from nitrogen-fixing biologically crusted soils in a cool desert environment, southeast Utah, USA. Ecol Process 2:16

Barr D (1999) Biotic and abiotic regulation of nitrogen dynamics in biological soil crusts. M.S. Thesis. Northern Arizona University, Flagstaff, AZ

Belnap J (2002a) Nitrogen fixation in biological soil crusts from southeast Utah, USA. Biol Fertil Soils 35:128–135

Belnap J (2002b) Impacts of off road vehicles on nitrogen cycles in biological soil crusts: resistance in different US deserts. J Arid Environ 52:155–165

Belnap J (2003) Factors influencing nitrogen fixation and nitrogen release in biological soil crusts. In: Belnap J, Lange OL (eds) Biological soil crusts: structure, function, and management. Springer, Berlin, pp 241–261

Belnap J, Lange O (2003) Biological soil crusts: structure, function, and management. Springer, Berlin

Belnap J, Munson SM, Field JP (2011) Aeolian and fluvial processes in dryland regions: the need for integrated studies. Ecohydrology 4:615–622. doi:10.1002/eco.258

Belnap J, Phillips SL, Troxler T (2006) Soil lichen and moss cover and species richness can be highly dynamic: the effects of invasion by the annual exotic grass Bromus tectorum, precipitation, and temperature on biological soil crusts in SE Utah. Appl Soil Ecol 32:63–76

Belnap J, Prasse R, Harper K (2003) Influence of biological soil crusts on soil environments and vascular plants. In: Belnap J, Lange OL (eds) Biological soil crusts: Structure, function, and management. Springer, Berlin

Beraldi-Campesi H, Hartnett HE, Anbar A, Gordon GW, Garcia-Pichel F (2009) Effect of biological soil crusts on soil elemental concentrations: implications for biogeochemistry and as traceable biosignatures of ancient life on land. Geobiology 7:348–359. doi:10.1111/j.1472-4669.2009.00204.x

Billings SA, Schaeffer SM, Evans RD (2003) Nitrogen fixation by biological soil crusts and heterotrophic bacteria in an intact Mojave Desert ecosystem with elevated CO2 and added soil carbon. Soil Biol Biochem 35:643–649

Bowker MA, Reed SC, Belnap J, Phillips SL (2002) Temporal variation in community composition, pigmentation, and F-v/F-m of desert cyanobacterial soil crusts. Microb Ecol 43:13–25. doi:10.1007/s00248-001-1013-9

Brankatschk R, Fischer T, Veste M, Zeyer J (2013) Succession of N cycling processes in biological soil crusts on a Central European inland dune. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 83:149–160

Breen K, Lévesque E (2008) The influence of biological soil crusts on soil characteristics along a high arctic glacier foreland, Nunavut, Canada. Arct Antarct Alp Res 40:287–297. doi:10.1657/1523-0430(06-098)

Caputa K, Coxson D, Sanborn P (2013) Seasonal patterns of nitrogen fixation in biological soil crusts from British Columbia’s Chilcotin grasslands. Botany 641:631–641

Castillo-Monroy AP, Maestre FT, Delgado-Baquerizo M, Gallardo A (2010) Biological soil crusts modulate nitrogen availability in semi-arid ecosystems: insights from a Mediterranean grassland. Plant Soil 333:21–34

Chamizo S, Cantón Y, Miralles I, Domingo F (2012) Biological soil crust development affects physicochemical characteristics of soil surface in semiarid ecosystems. Soil Biol Biochem 49:96–105

Ciais P, Sabine C, Bala G, Bopp L, Brovkin V, Canadell J, Chhabra A, DeFries R, Galloway J, Heimann M, Jones C, Le Quéré C, Myneni RB, Piao S, Thornton P, France PC, Willem J, Friedlingstein P, Munhoven G (2013) Carbon and other biogeochemical cycles. In: Stocker T, Qin D, Plattner G, Tignor M, Allen S, Boschung J, Nauels A, Xia Y, Bex V, Midgley P (eds) Climate change 2013—the physical science basis. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 465–570

David KAV, Fay P (1977) Effects of long-term treatment with acetylene on nitrogen-fixing microorganisms. Appl Environ Microbiol 34:640–646

Delgado-Baquerizo M, Morillas L, Maestre FT, Gallardo A (2013) Biocrusts control the nitrogen dynamics and microbial functional diversity of semi-arid soils in response to nutrient additions. Plant Soil 372(1–2):643–654

Dickson LG (2000) Constraints to nitrogen fixation by cryptogamic crusts in a polar desert ecosystem, Devon Island, N.W.T., Canada. Arct Antarct Alp Res 32:40–45. doi:10.2307/1552408

Drahorad S, Felix-Henningsen P, Eckhardt K-U, Leinweber P (2013) Spatial carbon and nitrogen distribution and organic matter characteristics of biological soil crusts in the Negev desert (Israel) along a rainfall gradient. J Arid Environ 94:18–26

Duan Z, Hongland X (2000) Effects of soil properties on ammonia volatilization. Soil Sci Plant Nutr 46:845–852

Elbert W, Weber B, Burrows S, Steinkamp J, Büdel B, Andreae MO, Pöschl U (2012) Contribution of cryptogamic covers to the global cycles of carbon and nitrogen. Nat Geosci 5:459–462

Eldridge DJ, Zaady E, Shachak M (2000) Infiltration through three contrasting biological soil crusts in patterned landscapes in the Negev, Israel. Catena 40:323–336

Eldridge DJ, Zaady E, Shachak M (2002) Microphytic crusts, shrub patches and water harvesting in the Negev Desert: the Shikim system. Landsc Ecol 17:587–597

Evans RD, Ehleringer JR (1993) A break in the nitrogen cycle in aridlands—evidence from delta-N-15 of soils. Oecologia 94:314–317. doi:10.1007/BF00317104

Evans RD, Johansen JR (1999) Microbiotic crusts and ecosystem processes. Crit Rev Plant Sci 18:183–225

Evans RD, Lange OL (2003) Biological soil crusts and ecosystem carbon and nitrogen dynamics. In: Belnap J, Lange OL (eds) Biological soil crusts: structure, function, and management. Springer, Berlin, pp 263–280

Field JP, Breshears DD, Whicker JJ, Zou CB (2011) Interactive effects of grazing and burning on wind- and water-driven sediment fluxes: rangeland management implications. Ecol Appl 21:22–32

Firestone MK, Davidson EA (1989) Microbiological Basis of NO and N2O Production and Consumption in Soil. In: Schimel MOA, Schimel DS (ed) Exchange of trace gases between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere: report of the Dahlem workshop on Exchange of trace gases between terrestrial ecosystems and the atmosphere, Berlin, Germany, Feb 19–24, 1989. Wiley, Chichester, New York, pp 7–21

Garcia-Pichel F, Belnap J (2003) Small-scale environments and distribution of biological soil crusts. In: Belnap J, Lange OL (eds) Biological soil crusts: structure, function, and management. Springer, New York, pp 193–201

Green LE, Porras-Alfaro A, Sinsabaugh RL (2008) Translocation of nitrogen and carbon integrates biotic crust and grass production in desert grassland. J Ecol 96:1076–1085

Guo Y, Zhao H, Zuo X, Drake S, Zhao X (2008) Biological soil crust development and its topsoil properties in the process of dune stabilization, Inner Mongolia, China. Environ Geol 54:653–662

Hardy RWF, Holsten RD, Jackson EK, Burns RC (1968) Acetylene-ethylene assay for N2 fixation—laboratory and field evaluation. Plant Physiol 43:1185–1207

Hartley AE, Schlesinger WH (2000) Environmental controls on nitric oxide emission from northern Chihuahuan desert soils. Biogeochemistry 50:279–300

Henriksson E (1957) Studies in the physiology of the lichen Collema. 1. The production of extracellular nitrogenous substances by the algal partner under various conditions. Physiol Plant 10:943–948. doi:10.1111/j.1399-3054.1957.tb07637.x

Holst J, Butterbach-Bahl K, Liu C, Zheng X, Kaiser AJ, Schnitzler JP, Zechmeister-Boltenstern S, Brüggemann N (2009) Dinitrogen fixation by biological soil crusts in an inner Mongolian steppe. Biol Fertil Soils 45:679–690. doi:10.1007/s00374-009-0378-7

Hooper DU, Johnson L (1999) Nitrogen limitation in dryland ecosystems: responses to geographical and temporal variation in precipitation. Biogeochemistry 46:247–293. doi:10.1023/A:1006145306009

Housman DC, Powers HH, Collins AD, Belnap J (2006) Carbon and nitrogen fixation differ between successional stages of biological soil crusts in the Colorado Plateau and Chihuahuan Desert. J Arid Environ 66:620–634. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2005.11.014

Housman DC, Yeager CM, Darby BJ, Sanford RL Jr, Kuske CR, Neher DA, Belnap J (2007) Heterogeneity of soil nutrients and subsurface biota in a dryland ecosystem. Soil Biol Biochem 39:2138–2149

Issa OM, Le Bissonnais Y, Defarge C, Trichet J (2001) Role of a cyanobacterial cover on structural stability of sandy soils in the Sahelian part of western Niger. Geoderma 101:15–30

Jeanfils J, Rack JP (1992) Identification and study of growth and nitrogenase activity of nitrogen-fixing cyanobacteria from tropical soil. Vegetatio 103:59–66

Jensen BB, Cox RP (1983) Direct measurements of steady-state kinetics of cyanobacterial N-2 uptake by membrane-leak mass-spectrometry and comparisons between nitrogen-fixation and acetylene-reduction. Appl Environ Microbiol 45:1331–1337

Johnson SL, Budinoff CR, Belnap J, Garcia-Pichel F (2005) Relevance of ammonium oxidation within biological soil crust communities. Environ Microbiol 7:1–12

Johnson SL, Neuer S, Garcia-Pichel F (2007) Export of nitrogenous compounds due to incomplete cycling within biological soil crusts of arid lands. Enviorn Microbiol 9:680–689

Jones K, Stewart WDP (1969a) Nitrogen turnover in marine and brackish habitats.3. Production of extracellular nitrogen by Calothrix scopulorum. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 49:475–488

Jones K, Stewart WDP (1969b) Nitrogen turnover in marine and brackish habitats.4. Uptake of extracellular products of nitrogen-fixing alga Calothrix scopulorum. J Mar Biol Assoc UK 49:701–716

Kershaw KA (1985) Physiological ecology of lichens. Cambridge University Press, London

Kothari A, Potrafka R, Garcia-Pichel F (2012) Diversity in hydrogen evolution from bidirectional hydrogenases in cyanobacteria from terrestrial, freshwater and marine intertidal environments. J Biotechnol 162:105–114. doi:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.04.017

Lange O, Green T (2003) Photosynthetic performance of a foliose lichen of biological soil-crust communities: long-term monitoring of the CO2 exchange of the Cladonia convolute under temperate habitat conditions. Bibl Lichenol 86:257–280

Lange O, Meyer A, Ullmann I, Zellner H (1991) Microklima, Wasserhehalt und Photosynthese von Flechten in der küstennahen Nebelezone der Namib-Wüste: Messungen während der herbstlichen Witterungsperiode. Flora 185:233–266

Li XJ, Li XR, Song WM, Gao YP, Zheng JG, Jia RL (2008) Effects of crust and shrub patches on runoff, sedimentation, and related nutrient (C, N) redistribution in the desertified steppe zone of the Tengger Desert, Northern China. Geomorphology 96:221–232

Liengen T (1999a) Environmental factors influencing the nitrogen fixation activity of free-living terrestrial cyanobacteria from a high arctic area, Spitsbergen. Can J Microbiol 45:573–581. doi:10.1139/cjm-45-7-573

Liengen T (1999b) Conversion factor between acetylene reduction and nitrogen fixation in free-living cyanobacteria from high arctic habitats. Can J Microbiol 45:223–229

Liu HSJ, Han XG, Li LH, Huang JH, Li X (2009) Grazing density effects on cover, species composition, and nitrogen fixation of biological soil crust in an Inner Mongolia steppe. Rangel Ecol Manag 62:321–327

Liu W, Song Y, Wang B, Li J, Shu W (2012) Nitrogen fixation in biotic crusts and vascular plant communities on a copper mine tailings. Eur J Soil Biol 50:15–20

Ludwig JA, Tongway DJ, Freudenberger D, Noble J, Hodgkinson KC (1997) Landscape ecology function and management: principles from Australia’s rangelands. CSIRO Publications, Collingwood

Maestre FT, Huesca M, Zaady E, Bautista S, Cortina J (2002) Infiltration, penetration resistance and microphytic crust composition in contrasted microsites within a Mediterranean semi-arid steppe. Soil Biol Biochem 34:895–898

Magee WE, Burris RH (1954) Fixation of N2 and utilization of combined nitrogen by Nostoc muscorum. Am J Bot 41:777–782

Marsh J, Nouvet S, Sanborn P, Coxson D (2006) Composition and function of biological soil crust communities along topographic gradients in grasslands of central interior British Columbia (Chilcotin) and southwestern Yukon (Kluane). Can J Bot 84:717–736. doi:10.1139/b06-026

Martin RE, Asner GP, Ansley RJ, Mosier AR (2003) Effects of woody vegetation encroachment on soil nitrogen oxide emissions in a temperate savanna. Ecol Appl 13:897–910

Marusenko Y, Bates ST, Anderson I, Johnson SL, Soule T, Garcia-Pichel F (2013) Ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria are structured by geography in biological soil crusts across North American arid lands. Ecol Process 2:9

Mayland HF, McIntosh TH (1966) Availability of biologically fixed atmospheric nitrogen-15 to higher plants. Nature 209:421–422

McCalley CK, Sparks JP (2008) Controls over nitric oxide and ammonia emissions from Mojave Desert soils. Oecologia 156:871–881. doi:10.1007/s00442-008-1031-0

McCalley CK, Sparks JP (2009) Abiotic gas formation drives nitrogen loss from a desert ecosystem. Science 326:837–840. doi:10.1126/science.1178984

Millbank JW (1982) The assessment of nitrogen-fixation and throughput by lichens. 3. Losses of nitrogenous compounds by Peltigera membranacea—Peltigera polydactyla—Lobaria pulmonaria in simulated rainfall episodes. New Phytol 92:229–234. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1982.tb03380.x

Miralles I, Domingo F, García-Campos E, Trasar-Cepeda C, Leirós MC, Gil-Sotres F (2012) Biological and microbial activity in biological soil crusts from the Tabernas desert, a sub-arid zone in SE Spain. Soil Biol Biochem 55:113–121

Munson SM, Belnap J, Okin GS (2011) Responses of wind erosion to climate-induced vegetation changes on the Colorado Plateau. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108:3854–3859. doi:10.1073/pnas.1014947108

Neff JC, Ballantyne AP, Farmer GL, Mahowald NM, Conroy JL, Landry CC, Overpeck JT, Painter TH, Lawrence CR, Reynolds RL (2008) Increasing eolian dust deposition in the western United States linked to human activity. Nat Geosci 1:189–195. doi:10.1038/ngeo133

Nohrstedt HO (1983) Conversion factor between acetylene-reduction and nitrogen fixation in soil—effect of water content and nitrogenase activity. Soil Biol Biochem 15:275–279. doi:10.1016/0038-0717(83)90071-8

Oswald R, Behrendt T, Ermel M, Wu D, Su H, Cheng Y, Breuninger C, Moravek A, Mougin E, Delon C, Loubet B, Pommerening-Röser A, Sörgel M, Pöschl U, Hoffmann T, Andreae MO, Meixner FX, Trebs I (2013) HONO emissions from soil bacteria as a major source of atmospheric reactive nitrogen. Science 341:1233–1235. doi:10.1126/science.1242266

Pepe-Ranney C, Koechli C, Potrafka R, Andam C, Eggleston E, Garcia-Pichel F, Buckley DH (2015) Noncyanobacterial diazotrophs mediate dinitrogen fixation in biological soil crusts during early crust formation. ISME J 10:287–298. doi:10.1038/ismej.2015.106

Peterjohn WT, Schlesinger WH (1990) Nitrogen loss from deserts in the southwestern United-States. Biogeochemistry 10:67–79

Pilegaard K (2013) Processes regulating nitric oxide emissions from soils. Phil Trans R Soc B 368:1–8. doi:10.1098/rstb.2013.0126

Pointing SB, Belnap J (2012) Microbial colonization and controls in dryland systems. Nat Rev Microbiol 10:551–562

Ravi S, Breshears DD, Huxman TE, D’Odorico P (2010) Land degradation in drylands: interactions among hydrologic-aeolian erosion and vegetation dynamics. Geomorphology 116:236–245. doi:10.1016/j.geomorph.2009.11.023

Ravi S, D’Odorico P, Breshears DD, Field JP, Goudie AS, Huxman TE, Li J, Okin GS, Swap RJ, Thomas AD, Van Pelt S, Whicker JJ, Zobeck TM (2011) Aeolian processes and the biosphere. Rev Geophys 49:RG3001. doi: 10.1029/2010RG000328

Rennie R, Rennie D, Fried M (1978) Concepts of 15N usage in dinitrogen fixation studies. Isotopes in biological dinitrogen fixation. FAO IAEA, Division of Atomic Energy in Food and Agriculture, Vienna, pp 107–130

Reynolds R, Belnap J, Reheis M, Lamothe P, Luiszer F (2001) Aeolian dust in Colorado Plateau soils: nutrient inputs and recent change in source. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:7123–7127

Rice WA, Paul EA (1971) Acetylene reduction assay for measuring nitrogen fixation in waterlogged soil. Can J Microbiol 17:1049–1056

Rogers SL, Burns RG (1994) Changes in aggregate stability, nutrient status, indigenous microbial-populations, and seedling emergence, following inoculation of soil with Nostoc muscorum. Biology and Fertility of Soils 18:209–215

Russow R, Veste M, Böhme F (2005) A natural 15N approach to determine the biological fixation of atmospheric nitrogen by biological soil crusts of the Negev Desert. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom 19:3451–3456. doi:10.1002/rcm.2214

Rütting T, Boeckx P, Müller C, Klemedtsson L (2011) Assessment of the importance of dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium for the terrestrial nitrogen cycle. Biogeosciences 8:1779–1791. doi:10.5194/bg-8-1779-2011

Shearer G, Kohl DH (1988) Natural 15N abundance as a method of estimating the contribution of biologically fixed nitrogen to N2-fixing systems: potential for non-legumes. Plant Soil 110:317–327. doi:10.1007/BF02226812

Silvester WB, Parsons R, Watt PW (1996) Direct measurement of release and assimilation of ammonia in the Gunnera-Nostoc symbiosis. New Phytol 132:617–625

Smith BE, Campbell F, Eady RR, Eldridge M, Ford CM, Hill S, Kavanagh EP, Lowe DJ, Miller RW, Richardson TH, Robson RL, Thorneley RNF, Yates MG (1987) Biochemistry of nitrogenase and the physiology of related metabolism. Philos Trans R Soc Lond Ser B Biol Sci 317:131–146. doi:10.1098/rstb.1987.0052

Spott O, Stange CF (2011) Formation of hybrid N(2)O in a suspended soil due to co-denitrification of NH(2)OH. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 174:554–567. doi:10.1002/jpln.201000200

Staal M, Te Lintel-Hekkert S, Harren F, Stal L (2001) Nitrogenase activity in cyanobacteria measured by the acetylene reduction assay: a comparison between batch incubation and on-line monitoring. Environ Microbiol 3:343–351. doi:10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00201.x

Stewart WDP (1967) Transfer of biologically fixed nitrogen in a sand dune slack region. Nature 214:603–604

Stewart WDP (1970) Algal fixation of atmospheric nitrogen. Plant Soil 32:555–588. doi:10.1007/BF01372896

Stewart KJ, Coxson D, Grogan P (2011a) Nitrogen inputs by associative cyanobacteria across a low arctic tundra landscape. Arct Antarct Alp Res 43:267–278

Stewart KJ, Coxson D, Siciliano SD (2011b) Small-scale spatial patterns in N2-fixation and nutrient availability in an arctic hummock–hollow ecosystem. Soil Biol Biochem 43:133–140

Stewart KJ, Lamb EG, Coxson DS, Siciliano SD (2011c) Bryophyte-cyanobacterial associations as a key factor in N2-fixation across the Canadian Arctic. Plant Soil 344:335–346

Stewart KJ, Brummell ME, Coxson DS, Siciliano SD (2012) How is nitrogen fixation in the high arctic linked to greenhouse gas emissions? Plant Soil 362:215–229

Strauss SL, Day TA, Garcia-pichel F (2012) Nitrogen cycling in desert biological soil crusts across biogeographic regions in the Southwestern United States. Biogeochemistry 108:171–182

Su H, Cheng Y, Oswald R, Behrendt T, Trebs I, Meixner FX, Andreae MO, Cheng P, Zhang Y, Pöschl U (2011a) Soil nitrite as a source of atmospheric HONO and OH radicals. Science 333:1616–1618. doi:10.1126/science.1207687

Su Y, Zhao X, Li A, Li X, Huang G (2011b) Nitrogen fixation in biological soil crusts from the Tengger desert, northern China. Eur J Soil Biol 47:182–187

Thiet RK, Boerner REJ, Nagy M, Jardine R (2005) The effect of biological soil crusts on throughput of rainwater and N into Lake Michigan sand dune soils. Plant Soil 278:235–251. doi:10.1007/s11104-005-8550-9

Thompson TL, Zaady E, Huancheng P, Wilson TB, Martens DA (2006) Soil C and N pools in patchy shrublands of the Negev and Chihuahuan Deserts. Soil Biol Biochem 38:1943–1955. doi:10.1016/j.soilbio.2006.01.002

Tucker TC, Westerman RL (1989) Gaseous loss of nitrogen from desert region soils. Arid Land Res Manag 3:267–280

Veluci RM, Neher DA, Weicht TR (2006) Nitrogen fixation and leaching of biological soil crust communities in mesic temperate soils. Microb Ecol 51:189–196. doi:10.1007/s00248-005-0121-3

Weber B, Berkemeier T, Ruckteschler N, Caesar J, Heintz H, Ritter H, Braß H (2015a) Development and calibration of a novel sensor to quantify the water content of surface soils and biological soil crusts. Methods Ecol Evol 7(1):14–22. doi:10.1111/2041-210X.12459

Weber B, Wu D, Tamm A, Ruckteschler N, Rodríguez-caballero E (2015b) Biological soil crusts accelerate the nitrogen cycle through large NO and HONO emissions in drylands. Proc Natl Acad Sci 112:15384–153849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1515818112

Williams WJ, Eldridge DJ (2011) Deposition of sand over a cyanobacterial soil crust increases nitrogen bioavailability in a semi-arid woodland. Appl Soil Ecol 49:26–31

Wrage N, Velthof GL, Van Beusichem ML, Oenema O (2001) Role of nitrifier denitrification in the production of nitrous oxide. Soil Biol Biochem 33:1723–1732. doi:10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00096-7

Wu N, Zhang YM, Downing A (2009) Comparative study of nitrogenase activity in different types of biological soil crusts in the Gurbantunggut Desert, Northwestern China. J Arid Environ 73:828–833

Yair A, Almog R, Veste M (2011) Differential hydrological response of biological topsoil crusts along a rainfall gradient in a sandy arid area: Northern Negev desert, Israel. Catena 87:326–333. doi:10.1016/j.catena.2011.06.015

Zaady E, Groffman PM, Standing D, Shachak M (2013) High N2O emissions in dry ecosystems. Eur J Soil Biol 59:1–7

Zhao Y, Xu M, Belnap J (2010) Potential nitrogen fixation activity of different aged biological soil crusts from rehabilitated grasslands of the hilly Loess Plateau, China. J Arid Environ 74:1186–1191

Zielke M, Ekker AS, Olsen RA, Spjelkavik S, Solheim B (2002) Errata: the influence of abiotic factors on biological nitrogen fixation in different types of vegetation in the high arctic, Svalbard. Arct Antarct Alp Res 34(3):293

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Cite this chapter

Barger, N.N., Weber, B., Garcia-Pichel, F., Zaady, E., Belnap, J. (2016). Patterns and Controls on Nitrogen Cycling of Biological Soil Crusts. In: Weber, B., Büdel, B., Belnap, J. (eds) Biological Soil Crusts: An Organizing Principle in Drylands. Ecological Studies, vol 226. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-30214-0_14

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-30214-0_14

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-319-30212-6

Online ISBN: 978-3-319-30214-0

eBook Packages: Biomedical and Life SciencesBiomedical and Life Sciences (R0)