Abstract

Growing evidence suggests that vascular perturbation plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). It appears to be a common feature in addition to the classic pathological hallmarks of amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques and neurofibrillary. Moreover, the accumulation of Aβ in the cerebral vasculature is closely associated with cognitive decline, and disruption of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) has been shown to coincide with the onset of cognitive impairment. Although it was originally hypothesized that the accumulation of Aβ and the subsequent disruption of the BBB were due to the impaired clearance of Aβ from the brain, a body of data now suggests an alternative hypothesis for vascular dysfunction in AD that amyloidogenesis promotes extensive neoangiogenesis leading to increased vascular permeability and subsequent hypervascularization. In this review, we discuss the role Aβ plays in angiogenesis of the neurovasculature and BBB and how it may contribute to the pathogenesis of AD. These studies suggest that interventions that directly or indirectly affect angiogenesis could have beneficial effects on amyloid and other pathways in AD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction: Alzheimer’s disease, the blood–brain barrier, and angiogenesis

For decades, the possible causes of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) have been debated, yet the true cause of this age-related neurological disorder remains unclear. Since the hallmark pathologies of AD are the amyloid beta (Aβ) plaques, the dominant hypothesis regarding AD (the ‘amyloid cascade hypothesis’) is that this 39- to 43-amino acid Aβ peptide is the neurotoxic cause of brain dysfunction and that its increased accumulation in the brain parenchyma leads ultimately to the memory loss and cognitive decline that are clinically characteristic of the disease [1]. However, efforts in developing effective AD therapeutics based on this hypothesis have so far proven unsuccessful. The reasons for this are complex, and clinical trial measures such as achieving effective drug levels, targeting an appropriate phase of the disease, adequate ‘end-point’ measures, and toxicity should all be considered. The failure of clinical trials based on the amyloid cascade hypothesis has also prompted a reassessment of AD pathogenesis. Although Aβ is still clearly implicated in AD, the field has been prompted to consider alternative hypotheses beyond Aβ as the central nexus of AD. The disease pathogenesis of AD is undoubtedly complex and multi-factorial. There is mounting evidence that changes in the cerebral and peripheral vasculature can lead to altered blood flow to the brain, and is a risk factor for developing AD [2, 3]. This alternative theory of AD pathogenesis has arisen through a variety of experimental AD studies in which blood–brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction and impaired cerebral blood flow (CBF) have been observed [4–9] and reviewed in [10, 11], suggesting that compromised clearance mechanisms at the BBB contribute to the accumulation of Aβ in the AD brain. New research also indicates that pathological cerebral angiogenesis may occur as a result of Aβ accumulation and result in BBB dysfunction in AD. Here, we review the current body of evidence regarding the vascular origins of AD and assess the conflicting reports regarding the role of cerebral angiogenesis in AD etiology.

Mechanisms of Alzheimer’s disease pathogenesis: the amyloid cascade hypothesis versus the vascular hypothesis

Alzheimer’s disease is the most common age-related neurological disorder of the first world. Biochemically, it is characterized by Aβ plaque formation, intraneuronal tau hyperphosphorylation, and neuronal loss [12, 13]. Elevated cytokine expression and microglial activation have also been observed and are contributors to the neuroinflammatory changes observed in post-mortem brains [14]. Clinically, the disease is characterized by worsening memory impairment, decline in cognitive ability, and eventual death [15]. Effective therapies for AD have so far eluded researchers and clinicians; however, the huge social and economic cost of caring for patients with AD means it is necessary to continue to research its causes in the hopes that effective therapies may be found.

For the last two decades, the dominant hypothesis regarding the cause of sporadic, non-familial AD has been the ‘amyloid cascade hypothesis’, which suggests that increased aberrant accumulation of the Aβ peptide in the brain leads to formation of plaque deposits, ultimately causing neuronal dysfunction and death. The Aβ peptide is generated from the cleavage of the amyloid precursor protein (APP), a normally expressed transmembrane protein (for extensive review, see [16]). Cleavage of APP by β-site cleaving enzyme and γ-secretase generates Aβ, whereas processing of APP by α-secretase precludes Aβ formation by cleaving the protein within the Aβ domain. The accumulation of the Aβ peptide in the brain is central to the amyloid cascade hypothesis, despite the fact that Aβ can be extensively present in the human brain in the absence of AD symptoms [17–20].

Despite this paradox, much attention has been focused on determining the mechanisms that lead to the accumulation of Aβ in AD. Research increasingly points to impaired clearance of brain Aβ as a more relevant factor in AD pathogenesis. A critical step in understanding the cause of AD is identifying what the initiating steps are in the neurodegenerative cascade. Two key vascular precursors to the neurodegenerative changes and Aβ deposition occurring in AD are the breakdown of the BBB [21, 22] and impaired CBF (hypoperfusion) [23]. In addition, the inflammatory changes observed in AD brains can lead to the upregulation of angiogenic mediators such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), causing pathological angiogenesis through which Aβ may further be generated [24]. The influence of these factors will be discussed in greater detail below, and collectively they provide a strong case that AD is a disease of vascular origin.

The blood–brain barrier in Alzheimer’s disease: vascular dysfunction

CBF in the brain is a key factor impacting BBB permeability and brain Aβ concentration. Although CBF decay is associated with normal aging, more severe CBF reductions have been detected in older individuals at a high risk of developing AD prior to the onset of Aβ accumulation and cognitive decline [4–8]. Recent studies into CBF in humans carrying the apolipoprotein E (ApoE) ϵ4 allele (the major genetic risk factor for late-onset AD) showed that these individuals had a larger regional proportion of deteriorated CBF compared with individuals not carrying the allele [25–28]. Several studies of AD pathogenesis in rats and mice have also described impaired CBF (reviewed extensively by Zlokovic [23]).

A compromised BBB in AD can result in the accumulation of unwanted and potentially neurotoxic molecules in the brain. The BBB is defined as the ‘microvasculature’ of the brain and is formed by a continuous layer of capillary endothelium joined by tight junctions that are generally impermeable (except by active transport) to most large molecules, including antibodies and other proteins (Figure 1) [29]. The unique properties of the BBB preclude the free exchange of solutes between the brain and blood, thereby protecting the brain from indiscriminate exposure to macromolecules, peptides, and other potentially toxic molecules that may enter via the peripheral circulation [29]. Physical breakdown of the BBB may result from disruption of tight junctions, adherens junctions, pericyte reduction, and degradation of the capillary basement membrane [23, 30]. Age-dependent loss of pericytes can lead to reduced expression of tight junction adaptor proteins such as occludin and ZO-1 and to an increase in bulk flow across the BBB [30].

Schematic diagram of the structure of the blood–brain barrier (BBB). The BBB is created by the tight apposition of endothelial cells lining blood vessels in the brain, forming a barrier between the circulation and the brain parenchyma. (A) A thin basement membrane, composed of laminin, fibronectin, and other proteins, surrounds the endothelial cells, associated astrocytes, and pericytes, providing both mechanical support and a barrier function. (B, C) Electron micrograph of an endothelial type II tight junction (simple overlap; black arrows). Magnification is 9,000× (B) with a magnified inset of 60,000× (C). Scale bars are 500 nm respective to the magnification.

We have previously examined the permeability of the BBB in the Tg2576 mouse model of AD. Using the quantitative Evans blue analysis, we demonstrated that the BBB is compromised in Tg2576 mice compared with non-transgenic controls [21]. Critically, BBB disruption was present in young (4-month-old) Tg2576 mice before any signs of AD were apparent, indicating that early BBB disruption may facilitate the accumulation of Aβ in the brain before other symptoms are apparent [21]. Zlokovic [29] has similarly described an age-dependent decline in BBB ability to clear Aβ in animal brains. These findings were also supported by a later study by our laboratory which showed BBB permeability and subsequent restoration of BBB integrity with Aβ immunization in Tg2576 mice compared with non-transgenic controls in 12- and 15-month-old mice [22].

Additional proteins at the BBB which act to regulate brain Aβ levels may be disrupted in AD. The receptor for advanced glycation products (RAGE) is a multi-ligand receptor that regulates the entry of peripheral Aβ to the brain and is also implicated in BBB breakdown and AD pathogenesis. It binds soluble Aβ in the nanomolar range, and its expression is upregulated by the variety of ligands it binds, including Aβ and pro-inflammatory cytokine-like mediators [31–34]. Because of this, increases in Aβ levels lead to the upregulation of RAGE, further facilitating the entry of Aβ into the cerebral neurons, microglia, and vasculature [34]. Beyond facilitating the entry of Aβ into the brain, in vitro studies have implicated RAGE in the vascular pathogenesis of AD by mediating apoptosis in the brain and suppression of CBF [31, 34].

In addition to RAGE, low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) is the main receptor clearing Aβ from the abluminal side of the BBB [35]. It is a member of the low-density lipoprotein receptor family and has been linked to AD both biochemically and genetically [36, 37] and may be involved in APP processing [35]. Deane and Zlokovic [35] used surface plasmon resonance analysis to show that LRP1 has a high affinity for Aβ1-40 and less affinity for β-sheet Aβ1-42. Interestingly, LRP1 is downregulated with age and in AD, and, although the mechanisms behind this downregulation remain unclear [35], research in mouse brains demonstrates that the presence of the ApoE 4ϵ allele blocks LRP1-mediated clearance of Aβ from the brain parenchyma [38]. Although there are many additional factors that ultimately impact Aβ concentration in the brain, including the rate of Aβ production and oligomerization [39–41], a disruption to these critical BBB proteins will have a significant influence in determining brain Aβ concentration and, in turn, its pathological consequences [42].

Pathological angiogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease

The case for a vascular etiology of AD is strengthened by the close association of AD with cerebrovascular amyloid angiopathy (CAA), which is present in approximately 90% of AD cases and 50% of the population over 90 [43]. CAA is characterized by the presence of Aβ in the pial and intracerebral small arteries and capillaries [44, 45] and is associated with microaneurysms and dementia [46]. Recently, angiogenesis has been proposed as a possible mediator of Aβ accumulation in AD, although there are conflicting reports regarding whether angiogenesis is a direct or indirect initiator of BBB disruption in response to direct activation by Aβ or by other mechanisms such as oxidative stress, inflammation, and hypoxia.

Research supporting a role for pathological angiogenesis in AD suggests that it occurs as a compensatory response to impaired CBF [47], which has been found in AD mouse models [48–50] and post-mortem studies [51]. The release of angiogenic cytokines such as thrombin and VEGF via stimulation of inflammatory pathways in AD also contributes to angiogenesis [24]. Vagnucci and Li [47] hypothesized a cycle of neurotoxicity and death initiated by the release of thrombin following Aβ-induced neuroinflammatory responses. The release of thrombin causes cerebral endothelial cells to secrete Aβ, promoting generation of reactive oxygen species and further endothelial damage. The accumulation of thrombin then stimulates further angiogenesis and Aβ production in a cycle of neurotoxic insult [47]. Other studies further support the interaction of Aβ with thrombin and fibrin throughout the clotting cascade to increase neurovascular damage and neuroinflammation [52–54]. Expression of other pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-1β, is known to be increased [55] during AD. These cytokines can then induce VEGF expression [56], yielding the growth of new blood vessels. Cultured astrocytes stimulated with Aβ [57, 58] release neuroinflammatory cytokines, resulting in the increased expression of VEGF. In mice, the reduction of Aβ-induced neuroinflammation [59] and angiogenesis [60] using the drug thalidomide has been documented.

There is substantial evidence implicating Aβ as a modulator of blood vessel density and vascular remodeling through angiogenic mechanisms [61]. Moreover, the mechanism by which Aβ stimulates angiogenesis is highly conserved and may be mediated through γ-secretase activity and Notch signaling. In vitro studies have demonstrated an angiogenic effect in human umbilical vein endothelial cells exposed directly to Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 [62]. Furthermore, the same cell line, when exposed to monomeric Aβ or γ-secretase inhibitors, exhibited an increase in the number of tip cells and branches [63]. Other studies in post-mortem human brains also found evidence of increased angiogenesis in the hippocampus, midfrontal cortex, substantia nigra pars compacta, and locus ceruleus of AD brains compared with controls [24]. Further analysis found no correlation between the number of microglia and angiogenesis or microglia with vessel density, suggesting that it may be the presence of Aβ that is initiating angiogenesis and subsequent vascular dysfunction.

The evidence for Aβ-related angiogenesis has been extended in vivo. When the chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane assay was used, embryos stimulated with Aβ1-40 and Aβ1-42 had an increase in vascular growth [62]. Studies in zebrafish that express green fluorescent protein in vascular endothelial cells corroborated these results. Treatment with γ-secretase inhibitors or Aβ resulted in significantly more vascular branching in the brain [63]. Studies in various APP mutant AD mouse models have also shown alterations in brain vasculature as a result of Aβ. APP23 mice exhibit significant blood flow alterations correlated with structural modifications of blood vessels [49]. Three-dimensional architectural analysis of young (3-month-old) and aged (up to 27-month-old) mice revealed significant alterations, particularly of the microvasculature. In young animals, small deposits were observed on microvessels, whereas in aged animals the vasculature appeared to abruptly end at amyloid plaques. Moreover, the brains of the aged mice exhibited a significant increase in β-3-integrin (a specific marker of activated endothelium) immunoreactivity, which was restricted to amyloid-positive vessels. Interestingly, brain homogenates from these mice resulted in the formation of new vessels in an in vivo angiogenesis assay that was blocked by a VEGF antagonist [56]. Overall, in both young and aged mice, the morphology of the vasculature appeared more dense and showed features typical of angiogenesis [64]. Although it should be noted that the vascular changes observed in these mice may be due to unrelated, ‘off-target’ effects of the APP mutation, this seems unlikely since the vascular changes observed in transgenic mice correlate well with vascular disturbances reported in human AD brains [21, 65].

In addition, the link between cerebral angiogenesis and hypoxia has been explored. Although cerebral hypoxic conditions are known to induce pro-angiogenic cytokines both in vitro[66] and in vivo[67], evidence of hypoxic angiogenesis is still unclear. For example, Aβ has been shown to sequester VEGF [68], suggesting limited bioavailability of the cytokine. This study by Yang and colleagues [68] proposes that VEGF co-aggregates with Aβ in AD brains. The authors proposed that the very slow release of VEGF from the co-aggregated VEGF/Aβ complex causes VEGF deficiency under the hypoxic conditions observed in AD brains. A related study attempted to examine the restorative effect of VEGF for AD in vivo[69] and found that intraperitoneal injection of VEGF in an AD mouse model ameliorated memory impairment in these mice compared with non-transgenic controls. Conflicting studies such as these on the role of pro-inflammatory cytokines in AD reflect the complexity of the etiopathology of AD. Although further work is needed to clarify the vascular response to conditions in the AD brain, these studies, taken together, show that disruptions to the neurovascular unit can influence cerebral ischemia, hypoxia, and neurodegeneration [70].

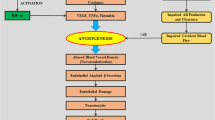

Finally, BBB dysfunction was initially identified in animal models of AD [21] and was later confirmed as a prominent, though unexplained, clinical feature of AD in patients [71]. Recently, we have demonstrated a significant increase in the incidence of disrupted tight junctions in aged Tg2576 AD model mice compared with controls and young animals. Moreover, we found that the pathology of the tight junction proteins occludin and ZO-1 was directly linked to an increased microvascular density but not apoptosis resulting from impaired CBF [65]. These data suggest that Aβ itself is vasculotropic and support the notion that amyloidogenesis-triggered hypervascularity may be the basis for BBB disruption in AD (Figure 2) [65]. Our observations in patients with AD parallel those in the animal model of AD in which we find a significant increase in cerebrovascular density compared with control patients. On the basis of these observations, we proposed a new hypothesis that is consistent with the literature relating to the BBB in AD: amyloidogenesis promotes extensive neoangiogenesis, leading to increased vascular permeability and subsequent hypervascularization in AD [65], which seeks to increase cerebrovascular flow. Although the direct involvement of Aβ in influencing angiogenesis is controversial, recent direct evidence supports this hypothesis. Cameron and colleagues [63] demonstrated that Aβ can directly influence angiogenesis via Notch signaling. The authors suggest that Aβ acts as competitive inhibitor to de-repress signals for angiogenesis.

Angiogenesis, not apoptosis, induces alterations in blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Representative confocal micrographs of tight junctions (TJ). Hippocampal sections from aged wild-type and Tg2576 AD model mice are stained with either (A) Occludin (red) or (B) ZO-1 (red), and double-stained for CD105 (green), a known marker of angiogenesis. All vessels stained for CD105 regardless of the TJ expression pattern. Scale bar represents 20 μm. (C) Aged Tg2576 mice had significantly increased CD105 protein levels in the hippocampus compared with age-matched wild-type mice (n = 7, *P <0.05). (D) The hippocampus of the AD patient had a significantly increased microvascular density (MVD), as measured by percentage area occupied by laminin staining, compared with the ND (no disease) patient (n = 4, ***P <0.001). Representative images of immunohistochemical staining for laminin in the cortex of the ND patient (E) and the AD patient (F). Scale bar represents 95 μm. Values represent mean ± standard error of the mean. Adapted from [65].

Immunotherapy continues to be explored as an experimental treatment option for AD. The unexpected negative vascular side effects seen in the early clinical trials of the human AD vaccine have prevented these therapies from reaching patients with AD; however, recent evidence suggests some optimism on this front [72]. We have recently examined whether immunization with Aβ peptides can resolve amyloidogenesis-triggered angiogenesis and hypervascularity in the Tg2576 AD mouse. We find that a dramatic reversion of hypervascularization follows immunization with Aβ [73]. This appears to be the first example of vascular reversion in which vascular density reverts to normal levels following therapeutic intervention. These findings clearly support a vascular angiogenesis model for AD pathophysiology and provide the first evidence that modulating angiogenesis repairs damage in the AD brain. In addition, we conducted a meta-analysis that quantified the endothelial (laminin) staining in the grey and white matter in the brain of a vaccinated patient with AD, as originally described by Boche and colleagues [74]. Overall, immunized AD brains had an apparent reduced vascular density compared with relevant controls. In the grey matter, 390 brain endothelia were identified in the untreated patient with AD compared with 262 brain endothelia in the immunized patient with AD (a 33% reduction after immunization). Similarly, in the white matter, 536 brain endothelia were identified in the untreated patient with AD compared with 402 brain endothelia in the immunized patient with AD (a 25% reduction after immunization). Clearly, this is a small data set but should direct research toward expanding these analyses. It would also be interesting, as an extension of this study, to determine whether this treatment regime could clear both parenchymal and vascular Aβ deposits. Overall, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that BBB leakiness in AD is due to Aβ-triggered angiogenesis resulting in hypervascularity and that neutralizing this signal by immunization with Aβ peptides removes the signal for angiogenesis. These data provide a strong link between brain vascularity and AD. However, in contrast to our recent findings, the over-inducement of angiogenesis was shown to reverse memory impairment and reduce AD-like neuropathologies in an AD mouse model [69]. Although this experiment cannot be directly compared with ours, it does support our idea that the key to AD pathogenesis is in the neurovasculature.

It has been reported that the murine PirB (paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B) and its human ortholog LilrB2 (leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B2), present in human brain, are receptors for Aβ oligomers, with nanomolar affinity leading to enhanced cofilin signaling. PirB contributes to memory deficits present in adult mice and mediates loss of synaptic plasticity in juvenile visual cortex. These findings imply that LilrB2 contributes to human AD neuropathology [75]; however, PirB is an alternate receptor for Nogo-B, a neurite outgrowth inhibitor, and mediates vascular protection and facilitates vascular remodeling mediated by monocytes and macrophages. Therefore, PirB may play a more general role in regulating macrophage responses to vascular injury and subsequent angiogenesis [76].

Recently, the anti-proliferative drug bexarotene (Targretin; Medicis, a division of Valeant, West Laval, Quebec, Canada), a retinoid-X-receptor (RXR) agonist and previously approved as an oral anti-cancer agent, was shown to reduce Aβ plaque burden and increase memory performance in an animal model of AD [77]. This study by Cramer and colleagues [77] interprets bexarotene acting on RXRs to upregulate transcription of ApoE, a protein that is implicated in Aβ plaque degradation. The improvement in hippocampal function is ultimately attributed by the reduction of plaque accumulation or turnover; nevertheless, other modes of action in AD are possible. These data are highly controversial; however, several reputable labs have reported that they have been unable to reproduce the key findings regarding the reduction in plaque burden and memory improvement in mice [78, 79]. Interestingly, one of these studies did report a reduction in soluble Aβ species [78], whereas another study observed behavioral improvement [80]. Nonetheless, other studies support bexarotene as a potential therapy for AD; for example, Fitz and colleagues [81] recently reported cognitive rescue and a reduction in A11-positive Aβ oligomers, and this was generally consistent with the findings from Cramer and colleagues [77]. The controversy surrounding the original article reflects the need for data to be reproduced by multiple labs before potential therapies such as bexarotene gain momentum as a panacea for AD. The response to the initial study reflects the desperation with which clinicians and patients are seeking an effective treatment for the disease. For this reason, bexarotene will undoubtedly continue to be assessed for its potential attenuation of AD pathology and effectiveness in AD therapy; however, other mechanisms of action for bexarotene may be found to be relevant for AD therapy. For example, bexarotene has been shown to directly exhibit an anti-angiogenic effect by downregulating pro-angiogenic factors, such as VEGF, by acting through the activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors [82]. Therefore, despite the controversy regarding bexarotene, studies that examine medications that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for treatment of other diseases such as cancer may direct research toward reversing cerebrovasculature angiogenesis and provide a new and unexpected therapeutic modality for AD.

Conclusions

Many working models have been proposed to explain, in entirety, the pathophysiology of AD, from the tau and amyloid hypotheses to the inflammation and lipodemic hypotheses. None of these models fully explains or fully incorporates all of the various aspects of the disease. It may be easier to fit these models by acknowledging that AD appears to be a syndrome rather than a single disease, and segmentation of this syndrome into various subcategories based on pathology or genetics may eventually provide explanations for each subcategory. This would also necessitate a reconsideration of the disparate disease features that have long confounded a unified chronopathological model of the disease. We had initially provided evidence of BBB leakiness and dysfunction in AD and this was expanded as the vascular model of AD. This BBB leakiness was first attributed to vascular dysfunction and deterioration but now appears to be clearly related to pro-angiogenic activity of amyloid itself. These new observations have allowed us to evolve the vascular model to incorporate our observations that hypervascularity appears in AD as a feature of the disease in human and animal brain (Figure 3). The question remains whether these observations can provide an explanation of AD as a syndrome or whether these observations apply to only a subcategory of the disease. It is certainly true that some patients with AD have no amyloid angiopathy at autopsy, whereas in others there is massive angiopathy and overall plaque burden. Similar discrepancies are seen with other biochemical features such as tau burden, but the clinical deterioration of these patients is very similar. Ultimately, for AD to be successfully treated, it may be necessary for us to consider that no single pharmacological intervention will effectively target all of the different causes at play. This can be likened to the treatment of cancer, in which the myriad causes and types may require different approaches to treatment for each patient. Although the use of anti-angiogenics in treating AD has demonstrated significant promise in experimental scenarios as we have described in this review, further work will be important for establishing the universal utility of anti-angiogenics for effective AD therapy.

Schematic model of how angiogenesis results in the breakdown of the blood–brain barrier (BBB) in Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Impaired cerebral blood flow (CBF) [4–8, 23, 25–28], tight junction (TJ) disruption [21, 22, 67], and disturbances in proteins regulating amyloid beta (Aβ) levels in the brain, such as receptor for advanced glycation products (RAGE) and lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1) [31–38], are factors contributing to elevated Aβ levels and subsequent angiogenesis [24, 48, 61, 67, 70]. Inflammation gives rise to elevated pro-angiogenic cytokines such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), further promoting vascular remodeling in the AD brain [47, 51–54]. Angiogenesis may also occur as a compensatory response to impaired CBF [47]. These processes lead to further Aβ secretion by endothelial cells, exacerbating angiogenesis and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS), endothelial damage, and neurotoxicity.

Abbreviations

- AD:

-

Alzheimer’s disease

- ApoE:

-

Apolipoprotein E

- APP:

-

Amyloid precursor protein

- Aβ:

-

Amyloid beta

- BBB:

-

Blood–brain barrier

- CAA:

-

Cerebrovascular amyloid angiopathy

- CBF:

-

Cerebral blood flow

- LilrB2:

-

Leukocyte immunoglobulin-like receptor B2

- LRP1:

-

Lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1

- PirB:

-

Paired immunoglobulin-like receptor B

- RAGE:

-

Receptor for advanced glycation products

- RXR:

-

Retinoid-X-receptor

- VEGF:

-

Vascular endothelial growth factor.

References

Hardy J, Selkoe DJ: The amyloid hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: progress and problems on the road to therapeutics. Science. 2002, 297: 353-356.

Kalaria RN: Small vessel disease and Alzheimer’s dementia: pathological considerations. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002, 13: 48-52.

Dickstein DL, Walsh J, Brautigam H, Stockton SD, Gandy S, Hof PR: Role of vascular risk factors and vascular dysfunction in Alzheimer’s disease. Mt Sinai J Med. 2010, 77: 82-102.

Bookheimer SY, Strojwas MH, Cohen MS, Saunders AM, Pericak-Vance MA, Mazziotta JC, Small GW: Patterns of brain activation in people at risk for Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2000, 343: 450-456.

Iadecola C: Neurovascular regulation in the normal brain and in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004, 5: 347-360.

Ruitenberg A, den Heijer T, Bakker SL, van Swieten JC, Koudstaal PJ, Hofman A, Breteler MM: Cerebral hypoperfusion and clinical onset of dementia: the Rotterdam Study. Ann Neurol. 2005, 57: 789-794.

Knopman DS, Roberts R: Vascular risk factors: imaging and neuropathologic correlates. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 20: 699-709.

Sheline YI, Morris JC, Snyder AZ, Price JL, Yan Z, D’Angelo G, Liu C, Dixit S, Benzinger T, Fagan A, Goate A, Mintun MA: APOE4 allele disrupts resting state fMRI connectivity in the absence of amyloid plaques or decreased CSF Abeta42. J Neurosci. 2010, 30: 17035-17040.

Kobayashi S, Tateno M, Utsumi K, Takahashi A, Saitoh M, Morii H, Fujii K, Teraoka M: Quantitative analysis of brain perfusion SPECT in Alzheimer’s disease using a fully automated regional cerebral blood flow quantification software, 3DSRT. J Neurol Sci. 2008, 264: 27-33.

Matsuda H, Kitayama N, Ohnishi T, Asada T, Nakano S, Sakamoto S, Imabayashi E, Katoh A: Longitudinal evaluation of both morphologic and functional changes in the same individuals with Alzheimer’s disease. J Nucl Med. 2002, 43: 304-311.

Bell RD, Zlokovic BV: Neurovascular mechanisms and blood–brain barrier disorder in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2009, 118: 103-113.

Glenner GG, Wong CW: Alzheimer’s disease: initial report of the purification and characterization of a novel cerebrovascular amyloid protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984, 120: 885-890.

Masters CL, Simms G, Weinman NA, Multhaup G, McDonald BL, Beyreuther K: Amyloid plaque core protein in Alzheimer disease and Down syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985, 82: 4245-4249.

Johnston H, Boutin H, Allan SM: Assessing the contribution of inflammation in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2011, 39: 886-890.

Banks WA: Drug delivery to the brain in Alzheimer’s disease: consideration of the blood–brain barrier. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2012, 64: 629-639.

Selkoe DJ: Biochemistry and molecular biology of amyloid beta-protein and the mechanism of Alzheimer’s disease. Handb Clin Neurol. 2008, 89: 245-260.

Alvarez G, Muñoz-Montaño JR, Satrústegui J, Avila J, Bogónez E, Díaz-Nido J: Regulation of tau phosphorylation and protection against beta-amyloid-induced neurodegeneration by lithium. Possible implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Bipolar Disord. 2002, 4: 153-165.

Selkoe DJ: The cell biology of beta-amyloid precursor protein and presenilin in Alzheimer’s disease. Trends Cell Biol. 1998, 8: 447-453.

Selkoe DJ: Translating cell biology into therapeutic advances in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1999, 399: A23-A31.

Selkoe DJ: Toward a comprehensive theory for Alzheimer’s disease. Hypothesis: Alzheimer’s disease is caused by the cerebral accumulation and cytotoxicity of amyloid beta-protein. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000, 924: 17-25.

Ujiie M, Dickstein DL, Carlow DA, Jefferies WA: Blood–brain barrier permeability precedes senile plaque formation in an Alzheimer disease model. Microcirculation. 2003, 10: 463-470.

Dickstein DL, Biron KE, Ujiie M, Pfeifer CG, Jeffries AR, Jefferies WA: A{beta} peptide immunization restores blood–brain barrier integrity in Alzheimer disease. FASEB J. 2006, 20: 426-433.

Zlokovic BV: Neurovascular pathways to neurodegeneration in Alzheimer’s disease and other disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011, 12: 723-738.

Desai BS, Schneider JA, Li JL, Carvey PM, Hendey B: Evidence of angiogenic vessels in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm. 2009, 116: 587-597.

Bertram L, McQueen MB, Mullin K, Blacker D, Tanzi RE: Systematic meta-analyses of Alzheimer disease genetic association studies: the AlzGene database. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 17-23.

Kim J, Basak JM, Holtzman DM: The role of apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2009, 63: 287-303.

Verghese PB, Castellano JM, Holtzman DM: Apolipoprotein E in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurological disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2011, 10: 241-252.

Thambisetty M, Beason-Held L, An Y, Kraut MA, Resnick SM: APOE epsilon4 genotype and longitudinal changes in cerebral blood flow in normal aging. Arch Neurol. 2010, 67: 93-98.

Zlokovic BV: The blood–brain barrier in health and chronic neurodegenerative disorders. Neuron. 2008, 57: 178-201.

Bell RD, Winkler EA, Sagare AP, Singh I, LaRue B, Deane R, Zlokovic BV: Pericytes control key neurovascular functions and neuronal phenotype in the adult brain and during brain aging. Neuron. 2010, 68: 409-427.

Yan SD, Chen X, Fu J, Chen M, Zhu H, Roher A, Slattery T, Zhao L, Nagashima M, Morser J, Migheli A, Nawroth P, Stern D, Schmidt AM: RAGE and amyloid-beta peptide neurotoxicity in Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 1996, 382: 685-691.

Mackic JB, Weiss MH, Miao W, Kirkman E, Ghiso J, Calero M, Bading J, Frangione B, Zlokovic BV: Cerebrovascular accumulation and increased blood–brain barrier permeability to circulating Alzheimer’s amyloid beta peptide in aged squirrel monkey with cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Neurochem. 1998, 70: 210-215.

Stern D, Yan SD, Yan SF, Schmidt AM: Receptor for advanced glycation endproducts: a multiligand receptor magnifying cell stress in diverse pathologic settings. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2002, 54: 1615-1625.

Deane R, Du Yan S, Submamaryan RK, LaRue B, Jovanovic S, Hogg E, Welch D, Manness L, Lin C, Yu J, Zhu H, Ghiso J, Frangione B, Stern A, Schmidt AM, Armstrong DL, Arnold B, Liliensiek B, Nawroth P, Hofman F, Kindy M, Stern D, Zlokovic B: RAGE mediates amyloid-beta peptide transport across the blood–brain barrier and accumulation in brain. Nat Med. 2003, 9: 907-913.

Deane R, Zlokovic BV: Role of the blood–brain barrier in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2007, 4: 191-197.

Kang J, Lemaire HG, Unterbeck A, Salbaum JM, Masters CL, Grzeschik KH, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Müller-Hill B: The precursor of Alzheimer’s disease amyloid A4 protein resembles a cell-surface receptor. Nature. 1987, 325: 733-736.

Hendriks L, van Duijn CM, Cras P, Cruts M, Van Hul W, van Harskamp F, Warren A, McInnis MG, Antonarakis SE, Martin J-J, Hofman A, Van Broeckhoven C: Presenile dementia and cerebral haemorrhage linked to a mutation at codon 692 of the beta-amyloid precursor protein gene. Nat Genet. 1992, 1: 218-221.

Deane R, Sagare A, Hamm K, Parisi M, Lane S, Finn MB, Holtzman DM, Zlokovic BV: apoE isoform-specific disruption of amyloid beta peptide clearance from mouse brain. J Clin Invest. 2008, 118: 4002-4013.

Miyazaki K, Ohta Y, Nagai M, Morimoto N, Kurata T, Takehisa Y, Ikeda Y, Matsuura T, Abe K: Disruption of neurovascular unit prior to motor neuron degeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. J Neurosci Res. 2011, 89: 718-728.

O’Kane RL, Martínez-López I, DeJoseph MR, Viña JR, Hawkins RA: Na(+)-dependent glutamate transporters (EAAT1, EAAT2, and EAAT3) of the blood–brain barrier. A mechanism for glutamate removal. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274: 31891-31895.

ElAli A, Hermann DM: ATP-binding cassette transporters and their roles in protecting the brain. Neuroscientist. 2011, 17: 423-436.

Zlokovic BV: New therapeutic targets in the neurovascular pathway in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurotherapeutics. 2008, 5: 409-414.

Vinters HV: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy. A critical review. Stroke. 1987, 18: 311-324.

Holton JL, Ghiso J, Lashley T, Rostagno A, Guerin CJ, Gibb G, Houlden H, Ayling H, Martinian L, Anderton BH, Wood NW, Vidal R, Plant G, Frangione B, Revesz T: Regional distribution of amyloid-Bri deposition and its association with neurofibrillary degeneration in familial British dementia. Am J Pathol. 2001, 158: 515-526.

Richard E, Carrano A, Hoozemans JJ, van Horssen J, van Haastert ES, Eurelings LS, de Vries HE, Thal DR, Eikelenboom P, van Gool WA, Rozemuller AJ: Characteristics of dyshoric capillary cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2010, 69: 1158-1167.

Jellinger KA: The enigma of vascular cognitive disorder and vascular dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2007, 113: 349-388.

Vagnucci AH, Li WW: Alzheimer’s disease and angiogenesis. Lancet. 2003, 361: 605-608.

Kara F, Dongen ES, Schliebs R, Buchem MA, Groot HJ, Alia A: Monitoring blood flow alterations in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease by in vivo magnetic resonance angiography at 17.6 T. Neuroimage. 2012, 60: 958-966.

Beckmann N, Schuler A, Mueggler T, Meyer EP, Wiederhold KH, Staufenbiel M, Krucker T: Age-dependent cerebrovascular abnormalities and blood flow disturbances in APP23 mice modeling Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003, 23: 8453-8459.

Thal DR, Capetillo-Zarate E, Larionov S, Staufenbiel M, Zurbruegg S, Beckmann N: Capillary cerebral amyloid angiopathy is associated with vessel occlusion and cerebral blood flow disturbances. Neurobiol Aging. 2009, 30: 1936-1948.

Pfeifer LA, White LR, Ross GW, Petrovitch H, Launer LJ: Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and cognitive function: the HAAS autopsy study. Neurology. 2002, 58: 1629-1634.

Cortes-Canteli M, Paul J, Norris EH, Bronstein R, Ahn HJ, Zamolodchikov D, Bhuvanendran S, Fenz KM, Strickland S: Fibrinogen and beta-amyloid association alters thrombosis and fibrinolysis: a possible contributing factor to Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron. 2010, 66: 695-709.

Zamolodchikov D, Strickland S: Abeta delays fibrin clot lysis by altering fibrin structure and attenuating plasminogen binding to fibrin. Blood. 2012, 119: 3342-3351.

Paul J, Strickland S, Melchor JP: Fibrin deposition accelerates neurovascular damage and neuroinflammation in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease. J Exp Med. 2007, 204: 1999-2008.

Pogue AI, Lukiw WJ: Angiogenic signaling in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroreport. 2004, 15: 1507-1510.

Schultheiss C, Blechert B, Gaertner FC, Drecoll E, Mueller J, Weber GF, Drzezga A, Essler M: In vivo characterization of endothelial cell activation in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Angiogenesis. 2006, 9: 59-65.

Fioravanzo L, Venturini M, Di Liddo R, Marchi F, Grandi C, Parnigotto PP, Folin M: Involvement of rat hippocampal astrocytes in beta-amyloid-induced angiogenesis and neuroinflammation. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2010, 7: 591-601.

Chiarini A, Whitfield J, Bonafini C, Chakravarthy B, Armato U, Dal Prà I: Amyloid-beta(25–35), an amyloid-beta(1–42) surrogate, and proinflammatory cytokines stimulate VEGF-A secretion by cultured, early passage, normoxic adult human cerebral astrocytes. J Alzheimers Dis. 2010, 21: 915-926.

Alkam T, Nitta A, Mizoguchi H, Saito K, Seshima M, Itoh A, Yamada K, Nabeshima T: Restraining tumor necrosis factor-alpha by thalidomide prevents the amyloid beta-induced impairment of recognition memory in mice. Behav Brain Res. 2008, 189: 100-106.

Ryu JK, McLarnon JG: Thalidomide inhibition of perturbed vasculature and glial-derived tumor necrosis factor-alpha in an animal model of inflamed Alzheimer’s disease brain. Neurobiol Dis. 2008, 29: 254-266.

Ethell DW: An amyloid-notch hypothesis for Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscientist. 2010, 16: 614-617.

Boscolo E, Folin M, Nico B, Grandi C, Mangieri D, Longo V, Scienza R, Zampieri P, Conconi MT, Parnigotto PP, Ribatti D: Beta amyloid angiogenic activity in vitro and in vivo. Int J Mol Med. 2007, 19: 581-587.

Cameron DJ, Galvin C, Alkam T, Sidhu H, Ellison J, Luna S, Ethell DW: Alzheimer’s-related peptide amyloid-beta plays a conserved role in angiogenesis. PLoS One. 2012, 7: e39598-

Meyer EP, Ulmann-Schuler A, Staufenbiel M, Krucker T: Altered morphology and 3D architecture of brain vasculature in a mouse model for Alzheimer’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 105: 3587-3592.

Biron KE, Dickstein DL, Gopaul R, Jefferies WA: Amyloid triggers extensive cerebral angiogenesis causing blood brain barrier permeability and hypervascularity in Alzheimer’s disease. PLoS One. 2011, 6: e23789-

Luo J, Martinez J, Yin X, Sanchez A, Tripathy D, Grammas P: Hypoxia induces angiogenic factors in brain microvascular endothelial cells. Microvasc Res. 2012, 83: 138-145.

Grammas P, Tripathy D, Sanchez A, Yin X, Luo J: Brain microvasculature and hypoxia-related proteins in Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2011, 4: 616-627.

Yang SP, Bae DG, Kang HJ, Gwag BJ, Gho YS, Chae CB: Co-accumulation of vascular endothelial growth factor with beta-amyloid in the brain of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2004, 25: 283-290.

Wang P, Xie ZH, Guo YJ, Zhao CP, Jiang H, Song Y, Zhu ZY, Lai C, Xu SL, Bi JZ: VEGF-induced angiogenesis ameliorates the memory impairment in APP transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011, 411: 620-626.

Iadecola C: The overlap between neurodegenerative and vascular factors in the pathogenesis of dementia. Acta Neuropathol. 2010, 120: 287-296.

Farrall AJ, Wardlaw JM: Blood–brain barrier: ageing and microvascular disease - systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol Aging. 2009, 30: 337-352.

Menéndez-González M, Pérez-Piñera P, Martínez-Rivera M, Muñiz AL, Vega JA: Immunotherapy for Alzheimer’s disease: rational basis in ongoing clinical trials. Curr Pharm Des. 2011, 17: 508-520.

Biron KE, Dickstein DL, Gopaul R, Fenninger F, Jefferies WA: Cessation of neoangiogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease follows amyloid-beta immunization. Sci Rep. 2013, 3: 1354-

Boche D, Zotova E, Weller RO, Love S, Neal JW, Pickering RM, Wilkinson D, Holmes C, Nicoll JA: Consequence of Abeta immunization on the vasculature of human Alzheimer’s disease brain. Brain. 2008, 131: 3299-3310.

Kim T, Vidal GS, Djurisic M, William CM, Birnbaum ME, Garcia KC, Hyman BT, Shatz CJ: Human LilrB2 is a β-amyloid receptor and its murine homolog PirB regulates synaptic plasticity in an Alzheimer’s model. Science. 2013, 341: 1399-1404.

Kondo Y, Jadlowiec CC, Muto A, Yi T, Protack C, Collins MJ, Tellides G, Sessa WC, Dardik A: The Nogo-B-PirB axis controls macrophage-mediated vascular remodeling. PLoS One.

Cramer PE, Cirrito JR, Wesson DW, Lee CY, Karlo JC, Zinn AE, Casali BT, Restivo JL, Goebel WD, James MJ, Brunden KR, Wilson DA, Landreth GE: ApoE-directed therapeutics rapidly clear beta-amyloid and reverse deficits in AD mouse models. Science. 2012, 335: 1503-1506.

Veeraraghavalu K, Zhang C, Miller S, Hefendehl JK, Rajapaksha TW, Ulrich J, Jucker M, Holtzman DM, Tanzi RE, Vassar R, Sisodia SS: Comment on “ApoE-directed therapeutics rapidly clear beta-amyloid and reverse deficits in AD mouse models”. Science. 2013, 340: 924-f-

Price AR, Xu G, Siemienski ZB, Smithson LA, Borchelt DR, Golde TE, Felsenstein KM: Comment on “ApoE-directed therapeutics rapidly clear beta-amyloid and reverse deficits in AD mouse models”. Science. 2013, 340: 924-d-

Tesseur I, Lo AC, Roberfroid A, Dietvorst S, Van Broeck B, Borgers M, Gijsen H, Moechars D, Mercken M, Kemp J, D’Hooge R, De Strooper B: Comment on “ApoE-directed therapeutics rapidly clear beta-amyloid and reverse deficits in AD mouse models”. Science. 2013, 340: 924-e-

Fitz NF, Cronican AA, Lefterov I, Koldamova R: Comment on “ApoE-directed therapeutics rapidly clear beta-amyloid and reverse deficits in AD mouse models”. Science. 2013, 340: 924-c-

Yen WC, Prudente RY, Corpuz MR, Negro-Vilar A, Lamph WW: A selective retinoid X receptor agonist bexarotene (LGD1069, targretin) inhibits angiogenesis and metastasis in solid tumours. Br J Cancer. 2006, 94: 654-660.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all of the members of the WAJ and DLD laboratories for their participation in these studies. This work was supported by grants to WAJ from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jefferies, W.A., Price, K.A., Biron, K.E. et al. Adjusting the compass: new insights into the role of angiogenesis in Alzheimer’s disease. Alz Res Therapy 5, 64 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1186/alzrt230

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/alzrt230