Abstract

Several studies have pointed to fine particulate matter (PM2.5) as the main responsible for air pollution toxic effects. Indeed, PM2.5 may not only cause respiratory and cardiovascular abnormalities but it may also affect other organs such as the liver. Be that as it may, only a few studies have evaluated the PM2.5 effects on hepatic tissue. Moreover, most of them have not analyzed the relationship between particles composition and toxicological effects. In this study, healthy rats were subjected to urban levels of PM2.5 particles in order to assess their structural and functional effects on the liver. During the exposure periods, mean PM2.5 concentrations were slightly higher than the value suggested by the daily guideline of the World Health Organization. The exposed rats showed a hepatic increase of Cr, Zn, Fe, Ba, Tl and Pb levels. This group also showed leukocyte infiltration, sinusoidal dilation, hydropic inclusions and alterations in carbohydrates distribution. These histologic lesions were accompanied by serological changes, such as increase of total cholesterol and triglycerides, as well as genotoxic damage in their nuclei. We also observed significant associations between several biomarkers and PM2.5 composition. Our results show that exposure to low levels of PM2.5 might cause histologic and serological changes in liver tissue, suggesting that PM2.5 toxicity is influenced not only by their concentration but also by their composition and the exposure frequency.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Currently, airborne particles are the largest human health risk in urban environments being responsible for thousands of deaths worldwide. Indeed, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), particles with a 2.5 µm diameter (PM2.5) are the best indicators to estimate the burden of disease attributable to ambient air pollution [1].

Numerous experimental, clinical and epidemiological studies have shown that exposures to PM2.5 not only is associated to respiratory and cardiovascular diseases but also to the enhancement of other pathologies [2, 3]. Indeed, previous evidence shows that PM2.5 may also affect organs such as the kidney, liver and even the nervous system [4,5,6]. Furthermore, PM2.5 exposure effects on non-target tissues such as the liver are unclear and the toxicokinetic mechanisms are not fully understood.

Few studies have evaluated the effects of suspended particles on hepatic tissue. They have reported inflammation with fibrosis [5, 7], steatosis with dyslipidemia [8, 9], abnormalities in glucose metabolism [10] and genotoxic effects [11] after exposure to suspended particles. However, most of these studies were done under laboratory conditions, with discontinuous or acute expositions to concentrated, standard or enriched particles. Furthermore, most of them did not employ PM2.5 nor analyze the relationship between particles composition and their toxicological effects. In fact, some particles-bounded substances, such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), may especially affect the liver due to their lipophilic nature and metabolism [12]. Thus, the aim of the present work was to evaluate the effect of sub-chronic PM2.5 exposure on liver tissue by exposing healthy animals to actual urban PM2.5 levels.

Materials and methods

Study design

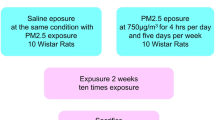

The study design has been previously described by Busso et al. [13]. Briefly, Wistar rats were exposed to urban PM2.5 for a 3 months period, in a two-chambers mobile animal facility located 7 m above the ground at the roof of the Chemistry Department of the Faculty of Exact, Physical and Natural Sciences, National University of Córdoba (FCEFyN-UNC). Four experimental exposures were done with four different groups during wintertime in 2014 (1 group), 2015 (2 groups) and 2016 (1 group). During these exposures, daily PM2.5 samples were collected, and elemental and PAHs compositions were measured. After the exposure period, the animals were sacrificed, and blood and histologic parameters were measured.

Exposure protocol

Twelve male Wistar rats were bred and kept in an air-filtered bioresource environment at the “J. Robert Cade” Foundation. At 5 weeks age, animals were randomly divided into two equal groups and each of them located in one of the mobile animal facility chambers, whose air uptake was connected to a Harvard Impactor (HI). In the control chamber, a 2.0 µm pore polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) filter (Zefluor, Millipore) was employed to remove fine particles. In the treatment chamber no filter was used; therefore, only large particles (> PM2.5) were removed by the HI impaction plate. Thus, the exposition period for each experimental group was 2010 ± 54 h, which is considered a sub-chronic exposure time [14]. Water and food were supplied ad libitum. Airflow in each chamber was set at 12.5 L min−1 to ensure a full air exchange at least 15 times per hour. Daily ambient temperature, relative humidity, precipitations, and wind speed were also recorded with a meteorological station located next to the mobile animal facility.

This exposure protocol was performed complying with the Institutional Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals guidelines of the FCEFyN-UNC and the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines of the USA National Institute of Health.

PM2.5 sampling and mass determination

Two daily PM2.5 samples were obtained employing HI and PTFE filters (Zefluor, Millipore). One sample (A), obtained from the control chamber was employed to measure PM2.5 mass and elemental composition, and a second sample (B), taken from the HI running simultaneously, was used for PAHs quantification. After getting the samples, filters A were conserved at 60 °C while filters B were stored at − 20 °C until analysis.

Particle mass was determined from filters A by gravimetric differences using a microbalance with a 0.01 mg mass resolution (Sartorius). Results were expressed as mean ± standard error (SE).

PAHs determination

Concentration of naphthalene (Nap), acenaphthylene (Acy), acenaphthene (Acp), fluorene (Flr), phenanthrene (Phe), anthracene (Ant), fluoranthene (Flt), pyrene (Pyr), benzo[a]anthracene (B[a]A), chrysene (Chr), benzo[b]fluoranthene (B[b]F), benzo[k]fluoranthene (B[k]F), benzo[a]pyrene (B[a]P), dibenzo[a,h]anthracene (D[ah]A), indeno[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene (Ind) and benzo[g,h,i]perylene (B[ghi]P) were measured employing high pressure liquid chromatography (Dionex Ultimate 3000, Thermo Scientific) with a C-18 reverse-phase column (LiChrospher 100 RP-18, 5 µm). These PAHs were selected as they have been classified as priority pollutants by the United States Environmental Protection Agency [15]. Particle-associated PAHs were extracted following the Tames et al. [16] protocol and measured as described in Supplementary Material (SM1, SM2) [17]. Recovery assays were also done for quality control employing pure standard and blank filters.

Calibration curves were also measured with PAHs standards (Sigma) with concentrations ranging from 0.05 to 25 µg L−1 (R2 for all compounds were over 0.9986; p < 0.005). Chromatograms were analyzed with Chromeleon 7.2.0.3765 (Dionex, Thermo Scientific). Particles-bounded PAHs masses were referred to the total volume of filtered air (pg m−3).

Blood and tissue collection

Prior to blood and tissue collection, animals were anesthetized and weighed for somatic index determination [13]. The abdominal and thoracic cavity was opened, and a 5 mL blood sample was obtained by cardiac puncture for hematologic and serologic measurements [18]. After that, the liver was excised, washed with cold (4 °C) phosphate buffered saline solution (PBS), dried with sorbent paper and weighed to determine the somatic index. The right medial lobe was excised and fragmented in three parts (7 mm × 7 mm). Each fragment was washed with cold PBS and gently compressed to remove excess blood. One fragment was weighed and dried at 60 °C up to constant weight to determine hydration and elemental composition. The second fragment was placed in 200 mL formaldehyde neutral buffer solution for histological assessment [19]. The third fragment was cut in smaller fragments (3 mm × 3 mm), washed with cold PBS and placed in 1 mL cold Hank’s balanced saline solution (HBSS) at 4 °C in the dark until its use for the comet assay.

Blood parameters

Red blood cells count (RBC), hemoglobin concentration, hematocrit, mean corpuscular volume (MCV), mean hemoglobin concentration (MHC), mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) and white blood cells count (WBC) were measured employing an automated hematology analyzer.

Serum of each blood sample was obtained as described by Burtis and Bruns [18]. Glycemia (enzymatic glycemia AA, Wiener lab.), triglycerides (TG Color® GPO/PAP AA, Wiener lab.), total cholesterol (enzymatic Colestat AA, Wiener lab.), high density lipoproteins (HDL Cholesterol Precipitation, Wiener lab.), alanine aminotransferase (GPT(ALT) UV, Wiener lab.) and aspartate aminotransferase (GOT(AST) UV, Wiener lab.) were measured. Values were expressed as mean ± standard error.

Elemental composition

Particles and tissue elemental composition were measured as previously reported by Busso et al. [13]. Levels of B, V, Cr, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Zn, As, Sr, Mo, Cd, Ba, Tl, Pb, and Bi were measured by mass spectroscopy inductively coupled plasma (Agilent 7500cx) employing high, middle and low concentration calibration curves (R2 > 0.9995).

Tissue analysis

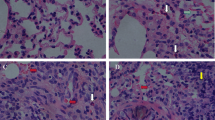

Liver fragments conserved in formaldehyde neutral buffer solution were processed with an automated tissue processor (Leica TP1020) and two 2 µm slides were obtained from each fragment with a rotary microtome. The samples were then mounted on slides, fixed, deparaffinized and stained. Hematoxylin/eosin (HE) and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains were employed [19]. 15 fields from each slide were examined blindly by two analysts at 100×, 400× and 1000× (Olympus CX31). Leucocyte infiltration (400×), fibrosis (400×), anisokaryosis (1000×), anisocytosis (1000×), hydropic degeneration (400×) and carbohydrates distribution (400×) were assessed employing a scale from 0 to 3 to rank the damage as previously described [20]. Hydropic degeneration was defined as the percentage of hepatocytes with hydropic inclusions per field. Carbohydrates distribution was evaluated in all the liver parenchyma. Thus, 15 hepatic lobules from the central region and 15 from peripheral parenchyma were analyzed. This variable was defined as the percentage of the lobule not reactive to PAS stain and categorized as 0, minimum or not observed (< 5%); 1, mild (> 5%); 2, moderate (> 30%), and 3, severe (> 50%). The presence of cholestasis, vascular congestion, or any other pathologic sign was also registered [21]. Hepatic sinusoids (pixels) were measured in 15 field micrographs per animal (1000×) with a computer image analysis software (Bio7, Freeware). Results of each group were expressed as mean ± SE.

Comet assay

The comet assay was performed as previously reported by Busso et al. [13] in order to assess DNA damage in liver cells. Cell suspensions were obtained from the liver fragment preserved in cold HBSS. 2 slides from each animal were assessed employing an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon) and 20 micrographs per slide (approximately 200 nuclei) were obtained and examined employing an image analysis software (Comet Score, TriTek Corp.; Sumerduck, USA). Percentage of nuclei without comets and percentage of different comets’ type were calculated. Also, slide mean of tail moment value (TMV, %) was calculated. Results were expressed as mean ± SE.

Statistical analysis

Total inhaled mass (TIM) of PM2.5 (µg) and PAHs (ng) during the total exposure period were calculated as previously reported [20]. Enrichment factors (EF) were calculated for inorganic elements to estimate their emission sources, employing Sr as reference element (EF < 10, natural; EF > 10, anthropic) [22]. Six diagnostic ratios commonly employed in exploratory analyzes were also calculated to asses PAHs emission sources (SM3) [23]. ANOVA with LSD Fisher ad-hoc test was employed to assess statistical differences between exposure periods. Student’s t test was used to analyze histological and serum parameters between treatments. Differences with a p value < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Pearson coefficients were also calculated to assess associations between tissue elemental composition and histological and serum parameters. Statistical analyses were done employing IBM SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corp.).

Results

Results from different exposure periods were analyzed altogether since PM2.5 mean concentration did not show significant differences (p = 0.9447) and PM2.5 TIM values were similar (283.2 ± 69.4 µg). Daily PM2.5 overall mean was 25.5 ± 2.3 µg m−3 (SM4) with a maximum value of 411.1 µg m−3 which could be related with forests fires that took place near the city during these days [24]. Significant negative associations were observed only between minimum temperature and humidity with PM2.5 levels (r2 = − 0.13, p < 0.0299 and r2 = − 0.15, p = 0.0098, respectively).

PM2.5 inorganic composition and EF are shown in Table 1. Fe and Zn were the most abundant elements while the other elements were two and three orders of magnitude lower. The correlation analysis showed that V, Mn, Fe, Zn, Cd, Ba, and Pb levels were positively associated with PM2.5 concentration (r2 > 0.35; p < 0.0278). The EF suggest that particles have both a natural and anthropic origin [22].

Particle-bounded PAHs, categorized by the number of aromatic rings, and diagnostic ratios are presented in Table 2. The 3-rings PAHs were the most abundant, while the other compounds were one order of magnitude lower. All PAHs were positively associated with particle concentration but only semi-volatile PAHs (4-rings) showed a significant value (r2 = 0.14, p = 0.0204). In addition, a negative correlation was found between ambient temperature and total PAHs (r2 = − 0.53, p < 0.001), which confirms the key role of the ambient temperature on the amount of particles-bounded PAHs [25].

To assess the toxic effects of PM2.5 on liver anatomy and functionality, tissue inorganic composition (Table 3) and blood and histologic parameters were measured in both control and treatment animals (Table 4). Tissue levels of Cr, Fe, Zn, Ba, Tl, and Pb were 1.33–2.32 times higher in treated than in control animals. Hemoglobin, MCV, WBC, platelets, total cholesterol, triglycerides, and AST levels were significantly higher in treated animals.

In addition, the treatment group presented mild diffuse lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate patches at portal spaces (Fig. 1) as well as vascular congestion of the lobule central vein (SM5). On the other hand, animals exposed to PM2.5 showed hepatic sinusoids dilation with some focal cholestasis (Fig. 2) and degenerative changes such as hydropic inclusions and loss of cytoplasmic borders (Fig. 3). PAS staining also revealed alterations in the intracellular carbohydrate’s distribution as indicated by a color decrease towards the central vein (SM6). A slight reduction of hepatic carbohydrates availability was also observed both in the central zone and in the periphery of the entire hepatic lobes, with a strong association to infiltration degree (r2 = 0.89), which allows us to infer an increase in the carbohydrates demand [26].

Several significant correlations were found between particles, blood, and tissue biomarkers: PM2.5 levels showed positive correlations with hepatic cell infiltration, carbohydrates distribution in both center and periphery, hemoglobin and total cholesterol (p < 0.0201); total PAHs a positive correlation with carbohydrates distribution (p < 0.0086) and negative correlation with HDL levels (p = 0.0008); infiltration degree showed positive correlation with WBC and MCV (p < 0.0287); and carbohydrates distribution showed a positive correlation with WBC (p < 0.0187).

Finally, an increase in the number of nuclei with comets was observed in exposed animals (46.3 ± 2.2%) compared to control animals (26.8 ± 1.5%) (p < 0.001). This increment was mainly due to type 2 and type 3 comets (from 25 to 75% of DNA in the tail). TMV also showed significant differences between treatments (41.2 ± 3.5 control group vs. 61.9 ± 2.6 treatment group, p < 0.001), indicating that DNA fragments in exposed animals were more scattered, therefore clastogenic effects of PM2.5 results in smaller DNA fragments.

Regarding genotoxic effects of several inorganic elements, levels of Cr correlated with the percentage of type 1comets (p = 0.0336), Zn with type 2 (p = 0.0290), Tl with type 3 (p = 0.0025) and Pb with type 4 (p = 0.0256). No significant correlation was found between particle-bounded PAHs levels and number of nuclei with comets. However, total PAHs TIM was associated with TMV (p = 0.0400). Furthermore, a strong association was found between TMV and 3-rings PAHs TIM (p = 0.0349), which were also the most abundant PAHs.

Discussion

In the present study, we assessed the effects of inhaled urban PM2.5 particles on the liver from healthy animals through the analysis of histological, biochemical and genotoxic parameters.

Overall particles levels were slightly above the 24 h-WHO guideline value (25 µg m−3) [1], which could be due to frequent thermal inversion events taking place over the city during wintertime [27]. This hypothesis is also supported by a negative association between the minimum temperature and PM2.5 levels. On the other hand, we found that PM2.5 sources were homogeneous, coming from both vehicle emissions and forest fires [28,29,30].

Regarding urban PM2.5 exposure, our results suggest that low levels of particles may induce several different hepatic changes. The first kind of changes is related to tissue composition. Our results showed that exposed animals increased their Cr, Fe, Zn, Ba, Tl, and Pb hepatic levels. This fact can be due to a simple bioaccumulation process or to a metabolic response. Previous authors already reported that particle-bounded metals such as Cr and Pb can bioaccumulate in rat livers [31, 32]. Furthermore, several other elements such as Ba and Tl can be excreted through bile [33], thus increasing their hepatic levels, even though their particles’ concentrations are low. On the other hand, particles might modify the organ normal function causing elemental accumulation. This hypothesis is supported by Wallenborn et al. [34] findings who demonstrated that instillation of exogenous 70Zn rises endogenous hepatic 65Zn levels, suggesting that exposure to exogenous elements may modify its normal metabolism. In agreement, Sørensen et al. [35] argued that exposure to PM2.5 induces a decrease of lung gas exchange surface and an increment of hemoglobin levels. Both effects could be positive regulators for Fe intestinal absorption and storage, therefore increasing its hepatic levels [36].

Low levels of urban PM2.5 may induce histologic and functional changes in the liver, as well. These alterations could be due to particles direct action [7], particles component’s metabolism [34, 37] or activation of response mechanisms [38]. Previous studies already demonstrated that some histologic or functional markers are related to cellular metabolic damage, such as lipids and transaminases elevation [39], while others such as MCV increase, leukocyte infiltration, and sinusoidal dilation, under chronic conditions, vary after these metabolic changes take place [10]. For instance, we found a linear relationship between the erythrocyte’s lipid content and the MCV, thus its increase in liver diseases may be related to changes in plasma lipids [40].

Many studies reported alterations in several of the mentioned hepatic tissue-damage markers after exposure to particulate matter [7, 9, 32, 38, 39, 41,42,43]. However, almost none of them were performed employing urban PM2.5, whose chemical composition is usually a complex mixture of organic and inorganic compounds. Despite this fact, our results mostly agree with previous findings. Actually, the only one relevant difference we found is in transaminases levels, since literature reports a simultaneous increase in AST and ALT levels. In our study, despite both enzymes were increased, only AST levels were significantly different in exposed animals. This result can be due to the fact that AST is a ubiquitous enzyme with very low diagnostic value for liver diseases in rats [44]; thus, its increase would be related to unspecific tissue damage, such as the lungs. Then, AST as a liver damage biomarker in rats under is not recommended. The fact we did not find changes in both enzymes allow as to conclude that actually exists cellular damage in rat livers although lesions are very incipient.

Regarding functionality, our results suggest that PM2.5 exposure fosters non-alcoholic fatty liver disease since total cholesterol and triglycerides were increased after PM2.5 exposure. These results agree with previous findings reported by Yeatts et al. [45] and Chuang et al. [46] in human epidemiologic and experimental studies. Furthermore, Ge et al. [8] reported an increase of glucose, insulin, total cholesterol and triglycerides in mice with an attenuated inflammatory response after exposure to concentrated PM2.5. Previous studies showed that the increase of blood lipids levels is usually found together with an insulin-resistance glycemia [8, 47]; however, we did not register such event because in our experiments animals were not food deprived, therefore glucose levels might be a result of diet. Despite this fact, we found a slight decrease in liver carbohydrates availability, which is also reported in insulin resistance conditions [48]. These overall findings agree with the histopathological mechanisms proposed by Zheng et al. [10], who reported impaired hepatic glycogen storage, glucose intolerance, and insulin resistance after exposure to PM2.5. In fact, we found several pathologic changes were found to be related to PM2.5 parameters in a dose-dependent form. For instance, hepatic cell infiltration, alteration of carbohydrates distribution in both center and periphery and total cholesterol levels increased as PM2.5 levels in the air increased. On the other hand, carbohydrates distribution diminished, and HDL levels increased when particle-bounded PAHs increased, which can be attributed to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor that may indirectly impair glucose hepatic metabolism [49] and inhibit apolipoprotein A–I gene expression [50].

Finally, genotoxic damage in liver tissues were also reported by other authors [7, 11]. Despite the different exposure pathways as well as particles composition found in these mentioned studies, our results indicate that particles inhalation would induce DNA damage even at low particles doses. Correlation analysis also suggests that clastogenic damage could be the result of an additive process rather than a single-dose process [51]. Additionally, many comet assay outcomes were proportional to the concentration of compounds with proven genotoxic nature [15, 52,53,54], indicating that particle composition has a fundamental role in genotoxic processes [7].

In brief, histologic, biochemical and genotoxic findings suggest mild liver damage in exposed animals that impairs carbohydrates metabolism regulation. In fact, exposure to PM2.5 triggers some events in target organs that exacerbate glucose consumption, as usually happens during systemic inflammatory events [55]. Under chronic PM2.5 exposure, liver inflammation may generate a pathological imbalance of the serum glucose concentration [26]. Glucose demand could be also exacerbated by leukocyte infiltration in different tissues [56]. This is supported by the positive correlation found between tissue carbohydrates depletion, WBC and infiltration degree. Since particulate matter can deregulate the insulin pathway [47], glucose consumption is altered; therefore, the liver sends carbohydrates without being able to reconstitute its reserves due to insulin dysregulation [10]. The constant glucose demand may induce its biosynthesis; thus, lipids are moved to provide energy for the process [57], in agreement with our findings. Furthermore, other events may cause the process to be further exacerbated, such as the alteration HDL quality, which decreases lipoproteins anti-inflammatory and antioxidant capacity [45, 58, 59], and the toxic effect derived from the metabolism of some PM2.5-bounded substances [33, 60].

Despite the restricted number of individuals employed or the lack of molecular markers measurements, such as insulin, we were able to demonstrate that exposure to low levels of urban PM2.5 represents a threat to non-target organs such as the liver. Indeed, particles not only altered the tissue elemental composition but also induced incipient histologic lesions accompanied by biochemical changes and DNA damage. These events suggest a hepatic impairment of carbohydrates metabolism and an incipient development of a non-alcoholic steatohepatitis phenotype. Furthermore, results suggest that PM2.5 toxicity is influenced not only by their concentration but also by their composition and exposure frequency.

Abbreviations

- PM2.5 :

-

Fine particulate matter

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- PAHs:

-

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

- HI:

-

Harvard Impactor

- PTFE:

-

Polytetrafluoroethylene

- Nap:

-

Naphthalene

- Acy:

-

Acenaphthylene

- Acp:

-

Acenaphthene

- Flr:

-

Fluorene

- Phe:

-

Phenanthrene

- Ant:

-

Anthracene

- Flt:

-

Fluoranthene

- Pyr:

-

Pyrene

- B[a]A:

-

Benzo[a]anthracene

- Chr:

-

Chrysene

- B[b]F:

-

Benzo[b]fluoranthene

- B[k]F:

-

Benzo[k]fluoranthene

- B[a]P:

-

Benzo[a]pyrene

- D[ah]A:

-

Dibenzo[a,h]anthracene

- Ind:

-

Indeno[1,2,3-c,d]pyrene

- B[ghi]P:

-

Benzo[g,h,i]perylene

- PBS:

-

Phosphate buffered saline solution

- HBSS:

-

Hank’s balanced saline solution

- HDL:

-

High density lipoproteins

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- HE:

-

Hematoxylin/eosin stain

- PAS:

-

Periodic acid-Schiff stain

- TMV:

-

Tail moment value

- TIM:

-

Total inhaled mass

- EF:

-

Enrichment factor

References

World Health Organization (2016) Ambient air pollution: a global assessment of exposure and burden of disease. World Health Organization, Geneva

Riva D, Magalhaes CB, Lopes A, Lancas T, Mauad T, Malm O et al (2011) Low dose of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) can induce acute oxidative stress, inflammation and pulmonary impairment in healthy mice. Inhal Toxicol 23:257–267

Wang C, Tu Y, Yu Z, Lu R (2015) PM2.5 and cardiovascular diseases in the elderly: an overview. Int J Environ Res Public Health 12:8187–8197

Kioumourtzoglou MA, Schwartz JD, Weisskopf MG, Melly SJ, Wang Y, Dominici F, Zanobetti A (2015) Long-term PM2.5 exposure and neurological hospital admissions in the northeastern United States. Environ Health Perspect 124:23–29

Zheng Z, Zhang X, Wang J, Dandekar A, Kim H, Qiu Y et al (2015) Exposure to fine airborne particulate matters induces hepatic fibrosis in murine models. J Hepatol 63:1397–1404

Miller MR, Raftis JB, Langrish JP, McLean SG, Samutrtai P, Connell SP et al (2017) Inhaled nanoparticles accumulate at sites of vascular disease. ACS Nano 11:4542–4552

Bourdon JA, Saber AT, Jacobsen NR, Jensen KA, Madsen AM, Lamson JS et al (2012) Carbon black nanoparticle instillation induces sustained inflammation and genotoxicity in mouse lung and liver. Part Fibre Toxicol 9:5

Ge CX, Qin YT, Lou DS, Li Q, Li YY, Wang ZM et al (2017) iRhom2 deficiency relieves TNF-α associated hepatic dyslipidemia in long-term PM2.5-exposed mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 493:1402–1409

Umezawa M, Nakamura M, El-Ghoneimy AA, Onoda A, Shaheen HM, Hori H et al (2018) Impact of diesel exhaust exposure on the liver of mice fed on omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids-deficient diet. Food Chem Toxicol 111:284–294

Zheng Z, Xu X, Zhang X, Wang A, Zhang C, Hüttemann M et al (2013) Exposure to ambient particulate matter induces a NASH-like phenotype and impairs hepatic glucose metabolism in an animal model. J Hepatol 58:148–154

Jackson P, Hougaard KS, Boisen AMZ, Jacobsen NR, Jensen KA, Møller P et al (2012) Pulmonary exposure to carbon black by inhalation or instillation in pregnant mice: effects on liver DNA strand breaks in dams and offspring. Nanotoxicology 6:486–500

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (1995) Toxicological profile for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. U.S. Department od Health and Human Services. Public Health Service

Busso IT, Vera A, Mateos AC, Amarillo AC, Carreras H (2017) Histological changes in lung tissues related with sub-chronic exposure to ambient urban levels of PM2.5 in Córdoba, Argentina. Atmos Environ 167:616–624

Barile FA (2013) Principles of toxicology testing. CRC Press, Boca Raton

United States Environmental Protection Agency (2017) Health effects. Notebook for hazardous air pollutants

Tames MF, Tavera Busso IY, Carreras HA (2019) Optimización de método para la determinación de hidrocarburos aromáticos policíclicos asociados a material particulado. Rev Int Contam Ambie 35:387–395

Wise SA, Sander LC, May WE (1993) Determination of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons by liquid chromatography. J Chromatogr A 642(1–2):329–349

Burtis CA, Bruns DE (2014) Tietz fundamentals of clinical chemistry and molecular diagnostics-e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences, Amsterdam

Bancroft JD, Floyd AD, Suvarna SK (2013) Bancroft’s theory and practice of histological techniques. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Busso IT, Mateos AC, Juncos LI, Canals N, Carreras HA (2018) Kidney damage induced by sub-chronic fine particulate matter exposure. Environ Int 121:635–642

Kumar V, Abbas AK, Aster JC (2017) Robbin’s basic pathology e-book. Elsevier Health Sciences, Amsterdam

Kabata-Pendias A, Mukherjee AB (2007) Trace elements from soil to human. Springer, Berlin

Slezakova K, Castro D, Delerue-Matos C, da Conceição Alvim-Ferraz M, Morais S, do Carmo Pereira M (2013) Impact of vehicular traffic emissions on particulate-bound PAHs: levels and associated health risks. Atmos Res 127:141–147

Achad M, López ML, Ceppi S, Palancar GG, Tirao G, Toselli BM (2014) Assessment of fine and sub-micrometer aerosols at an urban environment of Argentina. Atmos Environ 92:522–532

Tsapakis M, Stephanou EG (2005) Occurrence of gaseous and particulate polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the urban atmosphere: study of sources and ambient temperature effect on the gas/particle concentration and distribution. Environ Pollut 133:147–156

Wellen KE, Hotamisligil GS (2005) Inflammation, stress, and diabetes. J Clin Invest 115:1111–1119

Olcese LE, Toselli BM (2002) Some aspects of air pollution in Córdoba, Argentina. Atmos Environ 36:299–306

Bermudez GM, Jasan R, Plá R, Pignata ML (2012) Heavy metals and trace elements in atmospheric fall-out: their relationship with topsoil and wheat element composition. J Hazard Mater 213:447–456

Ferreyroa GV, Montenegro AC, Tudino MB, Lavado RS, Molina FV (2014) Time evolution of Pb(II) speciation in Pampa soil fractions. Chem Spec Bioavailab 26:210–218

Litter MI, Nicolli HB, Meichtry M, Quici N, Bundschuh J, Bhattacharya P, Naidu R (eds) (2014) One century of the discovery of arsenicosis in Latin America (1914–2014) As2014: proceedings of the 5th international congress on arsenic in the environment, Buenos Aires, Argentina, CRC Press

Damek-Poprawa M, Sawicka-Kapusta K (2003) Damage to the liver, kidney, and testis with reference to burden of heavy metals in yellow-necked mice from areas around steelworks and zinc smelters in Poland. Toxicology 186:1–10

Mani U, Prasad AK, Kumar VS, Lal K, Kanojia RK, Chaudhari BP, Murthy RC (2007) Effect of fly ash inhalation on biochemical and histomorphological changes in rat liver. Ecotox Environ Safe 68:126–133

Liu JGRA, Goyer RA, Waalkes MP (2008) Chapter 23: toxic effects of metals in Casarett and Doull’s toxicology: the basic science of poisons. McGraw-Hill, New York

Wallenborn JG, Kovalcik KD, McGee JK, Landis MS, Kodavanti UP (2009) Systemic translocation of 70Zn: kinetics following intratracheal instillation in rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 234:25–32

Sørensen M, Daneshvar B, Hansen M, Dragsted LO, Hertel O, Knudsen L, Loft S (2003) Personal PM2.5 exposure and markers of oxidative stress in blood. Environ Health Perspect 111:161

Papanikolaou G, Pantopoulos K (2005) Iron metabolism and toxicity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 202:199–211

Zhang W, Lei T, Lin ZQ, Zhang HS, Yang DF, Xi ZG et al (2011) Pulmonary toxicity study in rats with PM10 and PM2.5: differential responses related to scale and composition. Atmos Environ 45:1034–1041

Tan HH, Fiel MI, Sun Q, Guo J, Gordon RE, Chen LC et al (2009) Kupffer cell activation by ambient air particulate matter exposure may exacerbate non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Immunotoxicol 6:266–275

Xu J, Zhang W, Lu Z, Zhang F, Ding W (2017) Airborne PM2.5-induced hepatic insulin resistance by Nrf2/JNK-mediated signaling pathway. Int J Environ Res Public Health 14:787

Davidson RJ, Hamilton PJ (1978) High mean red cell volume: its incidence and significance in routine haematology. J Clin Pathol 31:493–498

Riediker M, Cascio WE, Griggs TR, Herbst MC, Bromberg PA, Neas L et al (2004) Particulate matter exposure in cars is associated with cardiovascular effects in healthy young men. Am J Respir Crit Care 169:934–940

Nalabotu SK, Kolli MB, Triest WE, Ma JY, Manne ND, Katta A et al (2011) Intratracheal instillation of cerium oxide nanoparticles induces hepatic toxicity in male Sprague-Dawley rats. Int J Nanomed 6:2327

Tomaru M, Takano H, Inoue KI, Yanagisawa R, Osakabe N, Yasuda A et al (2007) Pulmonary exposure to diesel exhaust particles enhances fatty change of the liver in obese diabetic mice. Int J Mol Med 19:17–22

Sharp P, Villano JS (2012) The laboratory rat. CRC Press, Boca Raton

Yeatts K, Svendsen E, Creason J, Alexis N, Herbst M, Scott J et al (2007) Coarse particulate matter (PM2.5–10) affects heart rate variability, blood lipids, and circulating eosinophils in adults with asthma. Environ Health Perspect 115:709

Chuang KJ, Yan YH, Cheng TJ (2010) Effect of air pollution on blood pressure, blood lipids, and blood sugar: a population-based approach. J Occup Environ Med 52:258–262

Conklin DJ (2013) From lung to liver: how does airborne particulate matter trigger NASH and systemic insulin resistance? J Hepatol 58:8–10

Vikram A, Jena G (2010) S961, an insulin receptor antagonist causes hyperinsulinemia, insulin-resistance and depletion of energy stores in rats. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 398:260–265

Sato S, Shirakawa H, Tomita S, Ohsaki Y, Haketa K, Tooi O et al (2008) Low-dose dioxins alter gene expression related to cholesterol biosynthesis, lipogenesis, and glucose metabolism through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated pathway in mouse liver. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 229:10–19

Naem E, Alcalde R, Gladysz M, Mesliniene S, Jaimungal S, Sheikh-Ali M et al (2012) Inhibition of apolipoprotein AI gene by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor: a potential mechanism for smoking-associated hypoalphalipoproteinemia. Life Sci 91:64–69

Pei Y, Halbrook RS, Li H, You J (2017) Homing pigeons as a biomonitor for atmospheric PAHs and PCBs in Guangzhou, a megacity in South China. Mar Pollut Bull 124:1048–1054

Matsumoto ST, Mantovani MS, Malaguttii MIA, Dias AL, Fonseca IC, Marin-Morales MA (2006) Genotoxicity and mutagenicity of water contaminated with tannery effluents, as evaluated by the micronucleus test and comet assay using the fish Oreochromis niloticus and chromosome aberrations in onion root-tips. Genet Mol Biol 29:148–158

García-Lestón J, Méndez J, Pásaro E, Laffon B (2010) Genotoxic effects of lead: an updated review. Environ Int 36:623–636

Rodríguez-Mercado JJ, Altamirano-Lozano MA (2013) Genetic toxicology of thallium: a review. Drug Chem Toxicol 36:369–383

Anderson JO, Thundiyil JG, Stolbach A (2012) Clearing the air: a review of the effects of particulate matter air pollution on human health. J Med Toxicol 8:166–175

Calder PC, Dimitriadis G, Newsholme P (2007) Glucose metabolism in lymphoid and inflammatory cells and tissues. Curr Opin Clin Nutr 10:531–540

Moran LA, Horton HR, Scrimgeour KG, Perry MD, Rawn D (2013) Principles of biochemistry. Pearson New International Edition

Ramanathan G, Yin F, Speck M, Tseng CH, Brook JR, Silverman F et al (2015) Effects of urban fine particulate matter and ozone on HDL functionality. Part Fibre Toxicol 13:26

Mendez R, Zheng Z, Fan Z, Rajagopalan S, Sun Q, Zhang K (2013) Exposure to fine airborne particulate matter induces macrophage infiltration, unfolded protein response, and lipid deposition in white adipose tissue. Am J Trans Res 5:224

Jin Y, Miao W, Lin X, Wu T, Shen H, Chen S et al (2014) Sub-chronically exposing mice to a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon increases lipid accumulation in their livers. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol 38:353–363

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr. Luis I. Juncos for his constructive comments and English language editing.

Funding

This work received partial support from Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Grant #11220090100999) and Secretaría de Ciencia y Técnica de la Universidad Nacional de Córdoba (Grant #30720110100529).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Tavera Busso, I., Mateos, A.C., González Peroni, A. et al. Hepatic alterations associated with fine particulate matter exposure. Toxicol Res. 36, 139–148 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43188-019-00014-4

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43188-019-00014-4