Abstract

A considerable proportion of people living in Western societies are single, i.e., they do not have an intimate partner. Recent research has indicated that about half of these instances are involuntary—people want to be in a relationship, but face difficulties in attracting partners. Within the context of an evolutionary theoretical framework, the current study aims to estimate the occurrence of involuntary singlehood in the Greek cultural context and to assess its impact on emotional wellbeing and on life satisfaction. Using an online sample of 735 Greek-speaking participants (431 women and 304 men), it was found that nearly 40% of those who were single were involuntarily so. It was also found that involuntary singles experienced significantly more negative emotions and lower life satisfaction than voluntary singles and people in a relationship.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Being single, i.e., without an intimate partner, is common in Western societies. For instance, studies in the USA have found that between one in three and one in four adults do not have an intimate partner (Pew Research Center 2006, 2013; Rosenfeld et al. 2015). It has been argued that one of the reasons why is that adaptations involved in mating have evolved in a context where mate choice was regulated or forced, and do not work optimally in the contemporary one where mate-choice is freely exercised (Apostolou 2015). This hypothesis predicts that a considerable proportion of singles would be involuntarily so—they are not single by choice, but because they face difficulties in establishing an intimate relationship. Consistent with this prediction, a recent study in the Greek cultural context found that about one in two people who were single were so because they had difficulty in finding a partner (Apostolou et al. 2018). However, one study is inadequate for establishing that a considerable proportion of the population is involuntary single. Accordingly, the current study aims to estimate the occurrence of involuntary singlehood in a different Greek-speaking sample.

Moreover, evolutionary theorizing predicts further that involuntary singlehood would have an impact on emotional wellbeing and life satisfaction (Apostolou 2016). In particular, involuntary singles are expected to experience more negative emotions such as loneliness and lower life satisfaction than those who are single by choice. Accordingly, the present study aims to examine how involuntary singlehood is associated with positive and negative emotions and life satisfaction. We will start our argument by examining in more detail why involuntary singlehood is expected to be in high prevalence, and subsequently, we will examine why it is expected to have an impact on emotions and life satisfaction.

Why Involuntary Singlehood Is in High Prevalence

Mate-seekers look for specific qualities in a partner, including good character and capacity to support a family (Buss 2017). They also look for mates who have similar characteristics to their own including age, social status, and personality (Figueredo et al. 2006). Such mates are not in ample supply; some may be off the mating market (e.g., they are married) or may not live in close proximity. Thus, attracting appropriate mates requires allocating considerable effort and resources. Mate-seekers have to invest, for example, money in improving their looks and time in building a social network from which prospective mates can be found.

In addition, there is considerable deception in the mating market (Haselton et al. 2005), which requires substantial more effort in order to find an appropriate mate. In particular, prospective mates may not be honest about their qualities. They may, for instance, act truthful and concerning, although they are in reality deceitful and uncaring. Prospective mates may also be dishonest about their intentions. For example, they may feign interest in forming a long-term intimate relationship, but what they actually have in mind is casual sex. Deciphering deceptive practices in the mating market requires individuals to invest substantially more effort in vetting potential partners and finding an appropriate mate.

In sum, securing a good mate is a time-consuming endeavor. Consequently, at any point in time, there would be several individuals who would be involuntarily single, because they have not found an appropriate mate yet. Nevertheless, this is unlikely to be the only or even the main reason behind the high prevalence of involuntary singlehood. Recent studies have indicated that people were single, because they faced difficulties in attracting mates and not temporarily because they have not found a partner yet.

More specifically, one study identified 76 reasons, and classified them in 16 factors and three domains, which could potentially drive people to be single (Apostolou 2017b). The three domains were the “difficulties with relationships” (included reasons such as not being good in flirting), “freedom of choice” (included reasons such as being free to flirt around), and “constraints” (included reasons such as having a serious health problem), with the first factor rated as being the most important one for being single. In the same vein, another study analyzed 13,429 responses from a Reddit thread, asking the question why men were single (Apostolou 2019). The responses were classified in 43 broader categories, with the most frequent ones being poor flirting skills, low self-confidence, poor looks, shyness, low effort, and bad experience from previous relationships, suggesting that the respondents were single because they faced difficulties in the domain of mating.

It has been proposed that the primary reason behind involuntary singlehood has been the mismatch between ancestral and modern conditions (Apostolou 2015). More specifically, the fact that those who fail to attract and retain mates will not have any offspring, translates into considerable evolutionary pressure placed on individuals to have evolved adaptations that would enable them to attract and retain mates (Buss 2017). These mechanisms have evolved to function optimally in the ancestral environment and may not work optimally in a modern environment, if the latter is different from the former, something which is known as the mismatch problem (Li et al. 2017; Maner and Kenrick 2010).

Anthropological and historical evidence has indicated that in ancestral human societies, mate-choice was regulated. In particular, evidence from contemporary pre-industrial societies, which resembled the way of life of ancestral ones, indicated that the typical mode of long-term mating was arranged marriage, where parents chose spouses for their children (Apostolou 2007, 2010; see also Walker et al. 2011). Historical evidence indicates further that, in known historical societies, arranged marriage was the norm (Apostolou 2012; Coontz 2006). Furthermore, men form male coalitions in order to fight other men and to monopolize their resources, including women, by force (Tooby and Cosmides 1988). Anthropological, historical, and archeological evidence suggests that such fights were frequent in ancestral societies (Bowles 2009; Puts 2016), but are considerably rarer in contemporary post-industrial ones (Pinker 2011).

Anthropological evidence from pre-industrial societies suggests also that, even in the context where marriages were arranged, individual mate choice could be exercised. To begin with, people could exercise more choice in later marriages which were less controlled by parents. Mate choice could also be exercised through divorce, which is as universal as marriage, over which parents had limited control. People could also exercise mate choice in extramarital relationships, which are frequently reported in pre-industrial societies (Apostolou 2017a). For instance, in a sample of 171 pre-industrial societies, Broude and Greene (1976) found that only in more than 70% extramarital relationships were relatively common for women and in more than 80% were relatively common for men.

This evidence indicates the presence of a substantial mismatch between ancestral and modern conditions in the area of mating: In ancestral human societies, mate-seekers would get mates predominately through their parents or through force, while in contemporary post-industrial societies, they do so through free courtship. Yet, the mechanisms which have enabled individuals to find mates in an arranged marriage and forced-mating context may fail to do so in a modern one, resulting in several individuals facing difficulties in attracting mates, prolonging in effect the period of time that they have to be single prior to securing a good mate.

On this basis, it can be predicted that involuntary singlehood would be in high prevalence in the population. One study has found evidence in support of this prediction (Apostolou et al. 2018). More specifically, in two online samples of Greek-speaking participants, about 56% and 43% of the singles respectively were involuntarily single. The current study aims to replicate this finding in a different sample.

The Price of Involuntary Singlehood

Emotions such as love and hate are generated by mechanisms which have evolved to motivate individuals to engage in actions that will increase their reproductive success or fitness (Tooby and Cosmides 2008). As reproductive success is closely associated with intimate relationships, emotions play a strong role in the mating domain: They motivate people to find and retain intimate partners. They do so by generating negative emotions (i.e., emotions which are unpleasant to those experiencing them) when individuals are in a fitness-decreasing situation, who are then motivated to take corrective action in order to get rid of these emotions. Similarly, by generating positive emotions (i.e., emotions which are pleasant to those experiencing them) when individual are in a fitness-increasing situation, they motivate people to remain in this situation in order to keep reaping the emotional rewards (Apostolou 2016). For instance, sexual lust, loneliness, and unhappiness motivate people to seek future partners, while sexual satisfaction, intimacy, and happiness motivate them to keep their current partners.

This theoretical framework generates the prediction that people who are involuntarily single will experience more negative and less positive emotions than people in an intimate relationship, with more negative emotions resulting in lower life satisfaction. These negative emotions constitute a normal part of the mating process—people who are not in an intimate relationship experience negative emotions which motivate them to allocate resources in attracting a partner. However, the prevalence of negative emotions coming from involuntary singlehood in the population is expected to be high due to the mismatch problem. That is, the mismatch problem would result in many people facing difficulties in attracting mates, which means that they will keep experiencing negative emotions.

Having no intimate partner is not always harmful for one’s reproductive success. People may stay single for some time in order to divert their resources in building qualities, such as education and social status, which are valued in a partner, and once they do so, to enter in the mating market. Or people may stay single in order to be able to flirt around and have casual sex with many different partners (Apostolou 2017b). These scenarios could potentially enable individuals to increase their fitness and are thus, not associated with negative emotions. Furthermore, many intimate relationships end at some point, so even if people who do not experience difficulties in attracting partners, may find themselves single for a short period of time. People in this category would experience fewer negative emotions such as loneliness than people who are involuntarily single, because the spell of singlehood would be shorter and because they anticipate that they will soon be in a relationship. Accordingly, it could be further predicted that people who are single by choice or are between relationships would experience fewer negative emotions and higher life satisfaction than those who are involuntarily single.

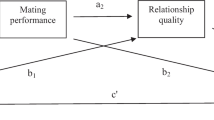

One study found that participants who indicated that they were not doing very well in starting and in keeping an intimate relationship, experienced more negative emotions and lower life satisfaction than those who indicated that they were doing well in these areas (Apostolou et al. 2019). Yet, this research did not examine differences between involuntarily single and other categories of marital status. Beckmeyer and Cromwell (2018) employed data from 744 unmarried emerging adults in the USA and examined differences in depressive symptoms, life satisfaction, and loneliness between participants who were romantically involved, single, and not at all interested in a romantic relationship, and single very interested in a romantic relationship. They found that, those who were in the single very interested in romantic relationships group reported more depressive symptoms than those in the other groups who were similar to each other. Furthermore, those who were romantically involved reported greater life satisfaction than both groups of singles who did not differ with each other. Finally, across the different groups, the single very interested in a romantic relationship group reported the highest loneliness.

The Beckmeyer and Cromwell (2018) study provides solid evidence that those who are involuntarily single experience stronger negative emotions and lower life satisfaction than those who are voluntarily single and those who are in an intimate relationship. It has limitations however, including that it did not distinguish between those who were involuntarily single because they face difficulties in attracting partners and those who were between relationships. A recent study found that about one in three singles classified themselves to be between relationships and not involuntarily single (Apostolou et al. 2018), with the two groups being likely to differ in terms of emotions and wellbeing (see above). In addition, the study focused on emerging adults, so its results cannot be generalized to other age groups. Furthermore, the study examined negative emotions but not positive emotions, which are expected to be also associated with singlehood status. The current study aimed to extend this line of work by testing the hypothesis that people who were involuntarily single would experience more negative emotions and lower life satisfaction than those who were single by choice, were between relationships, or were in a relationship. For this purpose, it employed a more diverge age groups in the Greek cultural context, and in addition to life satisfaction, it assessed the association of marital status with a range of positive and negative emotions.

Method

Participants

The research was designed and executed at a private university in the Republic of Cyprus. The survey was in Greek and was performed online. In order to recruit participants, the link of the study was forwarded to the emails of students and staff in various disciplines of different universities in Cyprus. In addition, we asked undergraduate and post-graduate students registered to psychology classes to post the link of our study to their Facebook page and forward the link to their friends and relatives. Finally, we posted the link of our study to the official website and the Facebook page of the university.

In the current study, 735 individuals (431 women and 304 men) took part. The mean age of women was 26.4 years (SD = 6.5), and the mean age of men was 28.3 years (SD = 8.4). In addition, 43.8% of the participants were single, 41.4% were in a relationship, 12.3% were married, and 2.4% were divorced. With respect to the singles, from those who were in the “between relationships” category 45.5% were men and 54.5% were women while the mean age was 22.5 years (SD = 3.8), in the “prefer to be single” category 43% were men and 57% women, and the mean age in the group was 21.7 (SD = 4.2). Moreover, in the “difficult to establish a relationship” category, 64.2% were men and 35.8% were women, with a mean age of 22.2 years (SD = 5.2) and in the “other” category, 47.8% were men and 52.2% were women with a mean age of 21.3 years (SD = 4.5).

Materials

The survey was constructed using Google forms, and consisted of five parts. In the first part, we measured life satisfaction using the Satisfaction With Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985), a five-item instrument participants had to rate using a 7-point Likert scale (1—totally disagree, 7—totally agree). In the second part, we assessed participants’ happiness using the Happiness Measures (HM), which consisted of two measures, namely an 11-point scale which the participant uses to check the point that comes closer to the perceived quality of happiness (0 indicating very low level of happiness and 10 very high level of happiness), and a scale that asks the participant to determine the percent of time spent in happy, unhappy, and neutral moods (Fordyce 1988).

In the third part, we employed the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule–Expanded Form (PANAS-X), which is a self-report measure that was specifically designed to assess the extent to which participants have experienced distinct emotions during the past few weeks (Watson and Clark 1999). In particular, we employed the four basic negative emotion scales consisting of 23 items, and the three basic positive emotion scales which consisted of 18 items. Participants recorded their answer using a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1—very slightly or not at all to 5—extremely. In the fourth part, we employed the DASS21 to measure depression, anxiety, and stress (Lovibond and Lovibond 1995). This instrument consisted of 21 statements that participants had to rate using a four-point Likert-type scale.

Finally, in the fifth part, demographic information was recorded including sex, age, and marital status. As part of the demographics of the study, if participants were single (i.e., they answered that they were single or divorced), they were asked to indicate why. Three options were given, namely “I find it difficult to attract a mate,” “I am between relationships,” and “I prefer to be single.” The order of presentation of the three options was randomized across participants. The order of presentation of the first four parts was counterbalanced across participants.

Results

Occurrence of Involuntary Singlehood

We started by calculating the frequencies of participants’ responses to the question of why they were single. The results are depicted in Fig. 1, where we can see that about 40% of the participants were involuntarily single. That is, they faced difficulties in attracting an intimate partner. In order get a better idea of the proportion of involuntarily single in our sample, we created a marital status variable, where the reasons for being single were used in the place of the single and divorced categories. In subsequent analysis, we have used this variable as a measure of marital status. The results are presented in Fig. 2, where we can see that, nearly one fourth of the participants in our sample were involuntarily single.

We would like to investigate whether the participants’ sex had an effect on marital status. For this purpose, we performed multinomial logistic regression, where the marital status variable was entered as the dependent variable and the sex was entered as the independent variable. In addition, participants’ age was entered as a covariate. Being in a relationship was chosen as the reference category. The results indicated a significant effect of sex [χ2(5, N = 762) = 56.65, p < .001], with the odds ratios indicating that men were 4.44 times more likely than women to be in the “I find it difficult to attract a mate,” 2.10 times more likely to be in the “other” reason for being single category, 1.89 times more likely in the “I am between relationships” and 1.80 times more likely in the “I prefer to be single” category than in the “in a relationship” category. Age was also significant [χ2(5, N = 762) = 191.88, p < .001], with the odds ratio indicating that older people were more likely to be married and less likely to be single than to be in a relationship.

The analysis above indicated that the marital status is likely to change as people get older; therefore, the occurrence of singlehood would decrease in older age. This finding raises the question of whether the proportion of those who are involuntarily single would also change as they get older. In order to find out, we performed a multinomial logistic regression, and we entered the reasons for being single variable as the dependent factor, and the age as the independent factor. Age was not significant [χ2(3, N = 459) = 5.47, p = .140], suggesting that the proportion of singles who were involuntary so remained relatively stable across different age groups.

Significant Effects

In our proposed theoretical framework, there would be differences in the emotions of people of different marital status. However, differences in the emotional state are also likely to be associated with differences in marital status, especially if it is in the abnormal range. For instance, those who are depressive or face severe anxiety, will be constrained in attracting and keeping a partner and they will thus, face an elevated probability of being involuntarily single. In order to partially control for this issue, we excluded from subsequent analysis 80 participants who scored in the severe range (as specified by the scoring instructions of the DASS instrument) for depression, anxiety, and stress. In particular, these participants scored 21 or more in the depression scale, 15 or more in the anxiety scale, and 26 or more in the stress scale.

For this group, 41.3% were involuntarily single, a bit more than the 39.6% for the remaining participants. Note that, for comparison purposes, the analysis discussed below was also repeated for the entire sample (i.e., when the 80 participants were included). Apart from small changes in the means, no other differences were found.

Our next step was to estimate whether participants in each marital status group differed in the positive and negative emotions they experienced. For this purpose, we ran a series of MANCOVAs for each subscale of the positive and negative emotions of the PANAS instrument. In particular, the emotions composing each scale were entered as the dependent variables, and the marital status was entered as the independent variable. In order to control for any confounding effects, and to examine possible interaction effects, we have also entered the sex as an independent variable. Finally, participants’ age was entered as a covariate.

The results for positive emotions are presented in Table 1, where we can see that marital status had a significant main effect on the “joviality” and on the “self-assurance.” In both cases, the lower mean scores were for the involuntary single group, and the highest for the married group. As indicated by the effect size, the largest difference was for the “happy” emotion, where the involuntary single group had the lowest mean score. Post-hoc analysis using Bonferroni indicated that the involuntarily single group was significantly different from the remaining groups.

Moving on to negative emotions, we can see from Table 2 that the marital status had a significant main effect on the “guilt” and the “sadness” scales. In all cases, the highest mean score was for the involuntarily single group, and the lowest was for the married group. As indicated by the effect size, the largest difference was over the “lonely” emotion, where the involuntarily single group had the highest mean score. Post-hoc analysis using Bonferroni indicated that the involuntarily single group was significantly different from all other groups. Finally, no significant interactions between the marital status and the sex were found for any of positive or negative emotions scale.

Also, note that for the “joviality” there were no significant main effects of sex and of age. For the “self-assurance,” the sex was significant [F(6, 664) = 4.54, p < .001, ηp2 = .039], with men scoring higher (M = 3.01, SD = 0.83) than women (M = 2.82, SD = 0.83). There was no significant main effect of age. In addition, there were no significant main effects of sex and of age for the “guilt.” For the “sadness,” the sex was significant [F(5, 660) = 2.48, p = .031, ηp2 = .018], with women scoring higher (M = 2.81, SD = 1.06) than men (M = 2.73, SD = 1). In addition, there was no significant main effect of age.

With respect to the Happiness Measures (HM), we ran an ANCOVA for the first part, where participants’ scores were entered as the dependent variable and participants’ marital status and sex were entered as the independent variables. In addition, age was entered as a covariate. The results indicated that there was a significant main effect of marital status [F(1, 651) = 79.04, p < .001, ηp2 = .108], but there were no other significant main effects or interactions. The lowest score was for the difficulty to attract a mate category (M = 5.83, SD = 2.15), followed by the between relationships (M = 6.65, SD = 1.81), the other reason for being single (M = 6.73, SD = 1.73), the preferred to be single (M = 7.04, SD = 1.65), in a relationship (M = 7.05, SD = 1.71), and the married (M = 7.24, SD = 1.25). Post-hoc analysis using Bonferroni indicated that the difficult to attract a mate group was significantly different from all other groups.

Moving on to the second part of the HM, we ran a MANCOVA, where the percentages spent in being happy, neutral, and unhappy were entered as the dependent variables, and participants’ marital status and sex were entered as the independent variables. In addition, age was entered as a covariate. The results indicated a significant main effect of marital status [F(15, 1980) = 2.70, p < .001, ηp2 = .020]. From Table 3, we can see that this effect was significant for the percentage of time feeling happy and unhappy, but not for the percentage of time feeling neutral. We can further see that the difficult to attract a mate group had the lowest score in the happy dimension, with post-hoc analysis using Bonferroni indicating that the scores of the participants in the difficult to attract a mate category were significantly different from those who were in the single by choice, in a relationship, and in the married categories. In addition, participants who indicated that they faced difficulties in attracting a partner had the highest score in the unhappy dimension, with post-hoc analysis indicating that their scores were significantly higher from the scores of participants who were in a relationship or married. Finally, age was not significant but there was a significant main effect of sex [F(3, 658) = 4.65, p = .003, ηp2 = .021], with women spending more time feeling unhappy (M = 24.9, SD = 16.8) than men (M = 22.8, SD = 18.7).

In order to examine whether marital status was associated with life satisfaction, we performed an ANCOVA, where the life satisfaction was entered as the dependent variable and the participants’ marital status and the sex were entered as the independent variables, while the age was entered as a covariate. The results indicated that there was a significant main effect of marital status [F(5, 653) = 12.36, p < .001, ηp2 = .086], but there were no other significant main effects or interactions. Participants who faced difficulties in attracting a partner had the lowest life satisfaction (M = 4.08, SD = 1.24), followed by participants who were single for other reasons (M = 4.58, SD = 1.09), participants who were between relationships (M = 4.74, SD = 1.18), those who preferred to be single (M = 4.89, SD = 1.07), those who were in a relationship (M = 5.03, SD = 1.09), and those who were married (M = 5.25, SD = 0.89). Post-hoc analysis using Bonferroni indicated that the difficult to attract a mate group was significantly different from all other groups. Finally, no significant main effects of sex and age were produced.

Discussion

Consistent with our original hypothesis, about 40% of the singles in our sample were so because they faced difficulties in attracting partners. We also found that men were more likely than women to be involuntarily single than to be in a relationship, while the proportion of singles who were involuntary so did not change with age. Participants who were involuntarily single experienced more negative emotions, such as loneliness, and less positive emotions, such as happiness, while they experienced lower life satisfaction than those who were single by choice or in an intimate relationship.

The present study offers strong evidence in support of the hypothesis that a considerable proportion of the population is involuntarily single, and this status is associated with negative emotions and low life satisfaction. If, following the proposed theoretical framework, we interpret this association as causal, we can say that a considerable proportion of the population experiences negative emotions due to being involuntarily single, which is partially explained by the mismatch problem. To put it the other way round, the mismatch between ancestral and modern conditions causes higher incidences of negative emotions, such as sadness and loneliness, by making people more prone to be involuntarily single.

We need to say that the mismatch hypothesis does not argue that in ancestral human societies, people could not exercise mate choice. Actually, one study examined data from the standard cross-cultural sample, and found that, in contemporary pre-industrial societies where marriages are arranged, there is a considerable space for individuals to exercise mate choice in premarital relationships, in extramarital relationships, and in forced sex or rape (Apostolou 2017a). Accordingly, there are reasons to believe that in ancestral human societies, people could exercise mate choice, giving rise to evolutionary pressures for adaptations to evolve that would enable people to attract and retain mates. The mismatch hypothesis argues that, in ancestral human societies, individuals were much more constrained in exercising mate choice than they are today in contemporary post-industrial societies. As a consequence, the adaptations involved in mating may be inadequate for enabling people to find mates on their own, resulting in several individuals facing prolonged spells of involuntary singlehood.

Furthermore, the results of the current study should not be interpreted to mean that involuntarily single people are always worst off in terms of emotions and wellbeing than people who are in an intimate relationship. A fitness-decreasing intimate relationship could potentially result in more negative emotions than involuntary singlehood. For instance, being with an abusive partner who frequently engages in extra-pair relationships may cause stronger negative emotions, such as anger, jealousy, and unhappiness than not having a partner. Accordingly, our findings should be interpreted to mean that people who are involuntarily singe are on average worst off than those who are willingly single or are in an intimate relationship, but considerable variations are expected in terms of emotions across the different groups.

Moreover, the financial crisis that started in Greece and in Cyprus in 2009 and it is still ongoing has resulted in a dramatic increase in unemployment. This increase has affected especially young people with unemployment rates reaching even 50% in the young age groups (see https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat). Given the relationships among capacity to provide resources and being gainfully employed and attracting a mate (Buss 2017), the high unemployment rates are an additional factor contributing to the high incidence of singlehood found in the current study. That is, the financial crisis has forced many people out of the labor force, and because having a job is considered an important quality in a mate, it may have effectively forced many people out of the mating market. Thus, future studies need to investigate the association of singlehood with economic factors such as unemployment. One way to do so would be to measure employment status, and subsequently to investigate whether it is associated with marital status.

Despite singlehood being a common state in Western societies, the research in the field is in early stages, with the current study being only the second one to have attempted to examine the association between singlehood, emotional wellbeing, and life satisfaction. Thus, much more research is necessary in order to understand the phenomenon of singlehood and its implications. To begin with, future studies need to replicate the current findings in different cultural settings. Moreover, people are likely to differ in how long they have been single, which in turn, could affect their emotional wellbeing and life satisfaction. Accordingly, future studies need to examine whether the length of singlehood is also associated with emotional wellbeing and life satisfaction. It would also be important to establish that periods of prolonged involuntary singlehood are associated with fitness outcomes. For instance, to investigate whether those who experience more prolonged spells of singlehood have fewer children than those who experience a shorter spells of singlehood. Similarly, research needs to identify the traits that make individuals more prone to long spells of singlehood.

Our study had several strengths, including the use of a large and diverse sample, employing an online format, which ensured anonymity, and using different, well-established and inclusive psychometric instruments in order to measure emotions and life satisfaction. Yet, in assessing the importance of our findings, caution should be drawn on some limitations. To begin with, we employed a non-probability sample, which means that what we found may not necessarily apply to the population. Moreover, our sample was relatively young; as people age, they eventually manage to attract long-term partners. Therefore, in older age groups, the involuntary singlehood and so, negative emotions and low life satisfaction would be in lower prevalence. In addition, we have found an association between negative emotions and involuntary singlehood which, on the basis of our theoretical framework, could be interpreted as causal. Still, our study was correlational and not experimental, so it could not establish such causality. Yet, an experimental study could not be performed as doing so would involve manipulating directly participants’ marital status. A longitudinal study could partially address the limitation of the present study, by following participants as they naturally change their marital status as they get older, and measure their emotions and life satisfaction.

Moving on, participants who chose the “other” and the “between relationships” options for singlehood may also be involuntarily single. The reason is that, although available, they did not choose the “I prefer to be single” option, suggesting that they did not prefer to be single. This being the case, the number of involuntary singles has been underestimated in the current study. Furthermore, the current study took place in a specific cultural context, which means that its findings may not readily generalize to other cultural contexts. In addition, the present study employed only one research method, namely survey, and future studies could attempt to triangulate its findings using different research methods.

Last but not least, the relationship between emotions, life satisfaction, and singlehood is most probably two-way: Involuntary singlehood would trigger negative emotions and low life satisfaction, but also strong negative emotions and very low life satisfaction may lead to involuntary singlehood. In the current research, we were predominantly interested in the former, so we removed from the sample participants’ who scored very high in depression, anxiety, and stress. Yet, even for the remaining participants, it can still be the case that higher levels of negative emotions and life satisfaction lower an individual’s mate value, which contributed to their current singlehood. These limitations, along with the very limited literature in the area and the high commonness of singlehood in post-industrial societies, mandate a strong need for future replication, and extension studies.

In sum, singlehood is a common state in post-industrial societies. The current research indicates that a considerable proportion of those who are single are likely to be involuntarily so, while involuntary singlehood is associated with more negative and fewer positive emotions and lower life satisfaction. Much more work is necessary, however, in order to understand this understudied phenomenon and its impact on wellbeing.

References

Apostolou, M. (2007). Sexual selection under parental choice: the role of parents in the evolution of human mating. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 403–409.

Apostolou, M. (2010). Sexual selection under parental choice in agropastoral societies. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31, 39–47.

Apostolou, M. (2012). Sexual selection under parental choice: evidence from sixteen historical societies. Evolutionary Psychology, 10, 504–518.

Apostolou, M. (2015). Past, present and why people struggle to establish and maintain intimate relationships. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 9, 257–269.

Apostolou, M. (2016). Feeling good: An evolutionary perspective on life choices. New York: Rutledge.

Apostolou, M. (2017a). Individual mate choice in an arranged marriage context: evidence from the standard cross-cultural sample. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 3, 193–200.

Apostolou, M. (2017b). Why people stay single: an evolutionary perspective. Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 263–271.

Apostolou, M. (2019). Why men stay single? Evidence from Reddit. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 5, 87–97.

Apostolou, M., Papadopoulou, I., & Georgiadou, P. (2018). Are people single by choice: involuntary singlehood in an evolutionary perspective. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences. Advance Online Publication.

Apostolou, M., Shialos, M., & Georgiadou, P. (2019). The emotional cost of poor mating performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 188–192.

Beckmeyer, J. J., & Cromwell, S. (2018). Romantic relationship status and emerging adult well-being. Emerging Adulthood. Advance Online Publication.

Bowles, S. (2009). Did warfare among ancestral hunter-gatherers affect the evolution of human social behaviors? Science, 324, 1293–1298.

Broude, G., & Greene, S. J. (1976). Cross-cultural codes on twenty sexual attitudes and practices. Ethnology, 15, 409–429.

Buss, D. M. (2017). The evolution of desire: strategies of human mating (4th ed.). New York: Basic Books.

Coontz, S. (2006). Marriage, a history: how love conquered marriage. New York: Penguin.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Figueredo, A. J., Sefcek, J. A., & Jones, D. N. (2006). The ideal romantic partner personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 41, 431–441.

Fordyce, M. W. (1988). A review of research on the happiness measures: a sixty second index of happiness and mental health. Social Indicators Research, 20, 355–381.

Haselton, M., Buss, D. M., Oubaid, V., & Angleitner, A. (2005). Sex, lies, and strategic interference: The psychology of deception between the sexes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 3–23.

Li, N. P., van Vugt, M., & Colarelli, S. M. (2017). The evolutionary mismatch hypothesis: implications for psychological science. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27, 38–44.

Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the depression anxiety & stress scales (2nd ed.). Sydney: Psychology Foundation.

Maner, J., & Kenrick, D. T. (2010). When adaptations go awry: functional and dysfunctional aspects of social anxiety. Social Issues and Policy Review, 4, 111–142.

Pew Research Center. (2006). Internet & American life project, online dating survey 2005. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2006/PIP_Online_Dating.pdf.pdf.

Pew Research Center. (2013). Online dating & relationships. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2013/PIP_Online%20Dating%202013.pdf.

Pinker, S. (2011). The better angels of our nature. New York: Penguin.

Puts, D. A. (2016). Human sexual selection. Current Opinion in Psychology, 7, 28–32.

Rosenfeld, M. J., Reuben, J. T., & Falcon, M. (2015). How couples meet and stay together, waves 1, 2, and 3: public version 3.04, plus wave 4 supplement version 1.02 and wave 5 supplement version 1.0 [Computer files]. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Libraries.

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1988). The evolution of war and its cognitive foundations. Institute for Evolutionary Studies Technical Report, 88, 1–15.

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2008). The evolutionary psychology of the emotions and their relationship to internal regulatory variables. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Johnes, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (3rd ed., pp. 114–137). New York: Guilford.

Walker, R. S., Hill, K. R., Flinn, M. V., & Ellsworth, R. M. (2011). Evolutionary history of hunter-gatherer marriage practices. PLoS One, 6, e19066.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1999). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule-expanded form. Iowa: the University of Iowa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Apostolou, M., Matogian, I., Koskeridou, G. et al. The Price of Singlehood: Assessing the Impact of Involuntary Singlehood on Emotions and Life Satisfaction. Evolutionary Psychological Science 5, 416–425 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-019-00199-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-019-00199-9