Abstract

Many people do not have an intimate partner, one reason being that they prefer to be single. The current research aimed to address the question what makes single life appealing, that is, to identify the possible advantages of being single. More specifically, Study 1 employed open-ended questionnaires on a sample of 269 Greek-speaking participants, and identified 84 such advantages. By using quantitative research methods on a sample of 612 Greek-speaking participants, Study 2 classified these advantages into 10 broader categories. The “More time for myself,” followed by the “Focus on my goals,” and the “No one dictates my actions,” were rated as the most important. Men found the “Freedom to flirt around” more important than women, while women found the Focus on my goals and the “No tensions and fights” more important than men. In addition, younger participants rated the Focus on my goals as more important than older ones. Furthermore, low scorers in mating performance found the identified advantages more important than high scorers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

People being single, that is, not having an intimate partner, has become increasingly common in contemporary societies (Cherlin, 2009; Klinenberg, 2012; Ortiz-Ospina, 2019; Tang et al., 2019; Wang & Parker, 2014). A nationally representative survey of American adults found that about half of those who were not in a committed relationship were not looking for one (Brown, 2020). One reason behind this trend is that individuals face difficulties in attracting and retaining intimate partners (Apostolou, 2015). Another reason is that singlehood can be appealing to many people, who make a conscious choice not to be in a relationship (DePaulo, 2007; Trimberger, 2006). For instance, one study recruited Greek and Chinese participants, and found that about one in 10 in the Greek, and about one in three in the Chinese sample, preferred to be single (Apostolou & Wang, 2019). The current research aims to investigate what makes single life attractive.

Why Not Having an Intimate Partner Can Be an Attractive Option

Mating is strategic in the sense that people employ specific strategies which direct their mating effort toward achieving specific mating goals (Gangestad & Simpson, 2000). One such strategy is to attract and retain mates in the long term, and invest heavily in children that come from these relationships (Buss & Schmitt, 2016). More specifically, children require considerable and prolonged parental investment to survive to sexual maturity (Kim et al., 2012). This fact means that people who fail to attract long-term partners face a considerable reduction in their chances to have their genetic material represented in future generations. In turn, strong selection pressures are generated, giving rise to behavioral mechanisms that motivate individuals to establish long-term intimate relationships (Buss, 2016; Dixson, 2009). Following this reasoning, we would expect that most people would prefer to be in an intimate relationship. Yet, a long-term mating strategy may involve staying single for a period of time (Apostolou, 2017). In addition, sexual strategies theory suggests that humans have evolved a plethora of mating strategies, not all of which involve long-term mating (Buss & Schmitt, 1993).

In more detail, people have well-defined preferences about what they want in an intimate partner (Buss, 2016). Such preferences include good education, having a good job and a good earning potential, and enjoying a good social status (Buss & Schmitt, 2019; Thomas et al., 2020; Walter et al., 2020). It follows that people who score high in these dimensions have better chances to attract high mate value long-term mates. Yet, people are not born with such qualities, but they need to develop them, for instance, to work hard to advance their careers that will increase their resource provision potential as well as their social standing. Doing so requires considerable resources such as time and money. Accordingly, it has been proposed that, in terms of reproductive success, it would pay for individuals to opt out from the mating market, and divert the bulk of their resources to developing their qualities and, at a later time, to reenter the mating market with better chances of attracting high-quality mates (Apostolou, 2017). Consistent with this argument, one common reason that people give for being single is to be able to focus on their careers (Apostolou, 2017; Apostolou et al., 2021).

Having different casual mates can potentially have several advantages. In particular, both men and women can gain sexual experiences or probe individuals for future long-term relationships (Buss, 2000; Buss et al., 2017). Men’s reproductive output is positively related to the number of women they gain sexual access to (Symons, 1979). Thus, for men in particular, having casual intimate relationships with different women can potentially increase their reproductive output (Buss & Schmitt, 1993). On this basis, it has been argued that people may opt out from the long-term mating market in order to be able to have casual relationships with different partners (Apostolou, 2017). In accordance with this argument, studies have found that being free to flirt around was a common reason for being single (Apostolou, 2017, 2019; Apostolou et al., 2021).

Moving on, sexual conflict theory (Arnqvist & Rowe, 2005; Buss, 2017) can give us further insights on why people prefer to be single. In particular, the interests of the two parties in an intimate relationship are not entirely aligned (Shackelford & Goetz, 2012). For instance, it can be beneficial for one party to have extra-pair relationships, which, however, is not in the other party’s best interest. Selection forces have forged behavioral mechanisms such as emotions to protect people’s mating interests (Tooby & Cosmides, 2008). For example, jealousy would protect people from being cheated (Buss, 2000). A bad relationship would trigger strong negative emotions including jealousy, anger, sadness, and loneliness, motivating people to terminate it. Although such negative emotions have the evolutionary logic of protecting people’s mating interests by prompting corrective action, they may also turn singlehood appealing because, by being single, individuals do not have to experience them. Consistent with this argument, people frequently report that they are single because they do not want to get hurt or cheated on and to avoid jealousy and disappointment (Apostolou, 2017; Apostolou et al., 2021).

Although not taking an evolutionary perspective, some authors have argued that single life is better than mated life, as the former is associated with more positive outcomes than the latter (DePaulo, 2007; Trimberger, 2006). For instance, it has been argued that singles have more time to develop themselves (DePaulo, 2007), allocate more time to do physical exercise so they can potentially be more healthy (Nomaguchi & Bianchi, 2004; see also Meltzer et al., 2013), have more friends (Adams, 1976; Sarkisian & Gerstel, 2016), and spend more time with their relatives (Sarkisian & Gerstel, 2016).

Sex, Age, and Mating Performance Effects

As discussed above, men’s but not women’s reproductive success is positively correlated with the number of mates they can gain sexual access to. On this basis, it can be predicted that men would be more likely than women to find singlehood appealing for enabling them to have more casual relationships. Furthermore, we have argued above that individuals would prefer to be single in order to be able to develop their strengths, and enter the mating market at a later stage, having better chances of success. This scenario is more likely to apply to younger individuals who have yet to develop their capacities. Accordingly, we predict that younger would be more likely than older individuals to find singlehood appealing for the purpose of developing their strengths.

Many people do not perform well in the domain of mating. More specifically, studies that have attempted to measure mating performance typically find that about one in two face difficulties in starting and/or keeping an intimate relationship (Apostolou & Wang, 2019; Apostolou et al., 2018, 2019). People who do not do well in the domain of mating are more likely to experience negative emotions such as anger and sadness than people who do better (Apostolou et al., 2019). As discussed above, such negative emotions may turn singlehood more appealing. Accordingly, we predict that low scorers in mating performance would find singlehood more appealing than high scorers.

The Present Study

Apostolou (2017) and later on Apostolou et al. (2021) examined the reasons why people were single. One conclusion from this line of work is that the singlehood phenomenon is complex and has many facets. One such facet is that people choose to be single because singlehood has several possible benefits. For instance, these studies have identified reasons such as “I want to be free to flirt around” and “I want to avoid conflict,” which could be interpreted as benefits of singlehood. Yet, to the best of our knowledge, there has not been any study that has specifically attempted to examine what people see as beneficial in being single, which is the purpose of the current work.

In particular, the present study aims to identify what people consider as possible advantages of being single (Study 1) and to classify them into broader categories, examining some of their predictors (Study 2). We hypothesize that the factors that would emerge would reflect focusing on developing one’s strengths, increasing opportunities for casual sex, and avoiding negative emotions. Nevertheless, given the complexity of the phenomenon and the limited research in the area, we consider our study to be explorative; that is, we cannot predict all the factors which are likely to emerge. In addition, the current research aimed to test the prediction that men would be more likely than women to find singlehood appealing in order to be free to exploit casual sex opportunities, younger people would be more likely than older ones to find singlehood appealing in order to have more resources available to divert in developing their strengths, and individuals who score low would find singlehood more appealing than individuals who score high in mating performance.

Study 1

Method

Participants

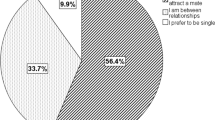

The study was designed and conducted at a private university in the Republic of Cyprus. Participants were recruited by promoting the study on social media, including Facebook and Instagram. In addition, the link of the study was forwarded to students and colleagues, who were asked to forward it further. In total, 269 Greek-speaking individuals (156 women, 113 men) took part. The mean age of women was 28.9 (SD = 10.11), and the mean age of men was 31.5 (SD = 12.4). With respect to the relationship status, 25.3% of the participants indicated that they were involuntarily single, 20.7% voluntarily single, 20.2% in a relationship, 15.8% in single-between relationships, and 11.8% married, and 6.2% chose the “other” option. Note that, as all people have experienced singlehood at some point in their lives, in our analysis, we included all participants, irrespectively of their relationship status.

Materials

The survey was in Greek, run online, and was constructed using Google Forms. It consisted of two parts. In the first part, participants were asked the following: “Write down some advantages that you think those who are single (i.e., they are not in an intimate relationship) enjoy,” and they were provided with space to record their answers. In the second part, demographic information was collected, including sex, age, and relationship status.

Analysis and Results

We recruited two independent graduate students (a man and a woman) to analyze the open-ended questionnaire data. Each assistant was asked to go through the responses and prepare a list of advantages associated with singlehood. The assistants were instructed to eliminate answers that contained multiple advantages, as they were difficult to interpret, and answers with unclear or vague wording. After processing about 30% of the responses, the assistants discussed and compared their respective list of acts, and then moved on to process the remaining responses. Each assistant produced one list of advantages, and subsequently, they compared their respective lists. The assistants agreed on most of the items. Where there was no complete overlap, the authors were consulted, and eventually, all the parties involved agreed to a final list of advantages. In total, 84 acts were identified and were listed in Table 1 (see supplementary material A for the frequencies of each item in the sample).

Study 2

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited with a method similar to Study 1. In total, 612 Greek-speaking individuals (384 women, 226 men, and two participants who did not indicate their sex) took part. The mean age of women was 31.4 (SD = 10.4), and the mean age of men was 36.1 (SD = 12.1). With respect to the relationship status, 27.6% of the participants indicated that they were in a relationship, 17.3% were involuntarily single, 17.2% were single-between relationships, 16.7% were voluntarily single, and 13.7% married, and 7.5% indicated the other option. Similarly to Study 1, as all people have some experience with singlehood, in our analysis we included all participants, irrespectively of their relationship status.

Materials

The survey was in Greek, run online, and was designed using Google Forms. It consisted of three parts. In the first part, participants were given the following scenario: “Below, you will find a number of possible advantages of being single. Consider the scenario that you are not in a relationship, and rate how important each of these advantages is to you.” Subsequently, participants were given the 84 advantages identified in Study 1, to rate on the following five-point Likert scale: 1 — Not at all important, 5 — Very important. In the second part, mating performance was measured using a previously developed instrument (Apostolou et al., 2018), which included five items that participants had to rate on the following scale: 1 — Strongly disagree, 5 — Strongly agree. A higher total score indicated higher mating performance. In the third part, demographic information was collected, including sex, age, and relationship status. The order of presentation of the question in each part was randomized across participants.

Data Analysis

In order to classify the 84 advantages identified in Study 1 into broader categories, we applied principal component analysis using the direct oblimin as the rotation method. In order to identify significant effects, we performed a series of MANCOVAs on each extracted factor. More specifically, the items which loaded to a given factor were entered as the dependent variables, the sex was entered as the categorical independent variable, and the age and mating performance as the continuous independent variables. An alternative strategy for analyzing the data would be to run one MANCOVA test, where the extracted factors would enter as the dependent variables. However, doing so would prevent us from accurately detecting sex, age, and mating performance effects. For instance, if some items composing a given factor were rated higher by men while others were rated higher by women, these differences would cancel out when the individual items would collapse to a single variable that would reflect the factor in question.

Results

The Advantages of Being Single

The KMO statistic was 0.98, indicating that our sample was very good for principal component analysis to be performed. Overall, 10 broader advantages of singlehood emerged. The Cronbach’s α for each factor ranged from 0.81 to 0.96 (Table 1). Furthermore, we performed principal component analysis on the 10 extracted factors, which failed to classify them into broader domains.

As we can see from Table 1, the first advantage to emerge was the “No one dictates my actions,” where participants indicated that one advantage of singlehood was not having anyone telling them what to do, controlling their behaviors, and explaining their actions. Another advantage was “Not getting hurt” by separations, cheating, and episodes of jealousy. In the “Better control of what I eat” advantage, participants indicated that not having an intimate partner would give them more control in regulating their food intake. In the “Focus on my goals” advantage, by being single, people would be able to divert their energy to achieving their goals, including advancing their studies and careers. Participants also indicated that not being in an intimate relationship gave them more “Freedom to flirt around.”

Moreover, another advantage of being single was that people could “Save resources,” such as time allocated to care for an intimate partner or resolve a relationship’s problems. Participants indicated further that not being in a relationship would give them more “Peace of mind,” less stress, and fewer problems to deal with. In the “More time for myself,” by not being in a relationship, people had more time available that they could allocate to know better and improve themselves, and do the things they liked, such as spending time with their friends and planning their time as they wished. In the “No tensions and fights” factor, participants indicated that an advantage of being single was no whining, no tensions and fights, and no criticism from a partner. Finally, in the “Not do things I dislike” advantage, by being single, people did not have to do things they did not like, such as spending time with their partners’ parents and friends or having sex.

In order to examine which advantages were considered more important, we estimated the means for each one, and we placed them in a hierarchical order in Table 2. We can see that, at the top of the hierarchy, was the More time for myself, followed by the Focus on my goals, and the No one dictates my actions. At the bottom of the hierarchy were the Save resources, the Not do things I dislike, and the Better control of what I eat.

Significant Sex, Age, and Mating Performance Effects

In total, 10 MANCOVA tests were performed. In order to avoid the problem of alpha inflation arising from multiple comparisons, Bonferroni correction could be applied by setting alpha to 0.005 (0.05/10). As we can see from Table 2, significant sex differences were found for the Focus on my goals and the No tensions and fights, where women gave higher scores than men, and for the Freedom to flirt around, where men gave higher scores than women. For the “Not have to do things I do not want to do,” women gave significantly higher scores to the “If I want, I can abstain from sex” item (M = 3.07, SD = 1.45) than men (M = 2.61, SD = 1.46), while for the “Fewer expenses” item, men gave significantly higher scores (M = 3.41, SD = 1.45) than women (M = 2.96, SD = 1.42).

Age was significant for most factors. As indicated by the effect size, the largest effects were for the Not do things I dislike and the More time for myself advantages. In both cases, the age coefficient was positive, indicating that older participants gave higher scores than younger ones. Moreover, with the exception of the Better control of what I eat, mating performance was significant for all factors. Most effects were moderate or large. In addition, in all cases, the coefficient of mating performance was negative, indicating that lower scorers in this dimension rated the identified factors as more important (see supplementary material B for the estimation of the regression coefficients).

Discussion

In the current research, we identified 84 possible advantages of being single, and we classified them into 10 broader categories. Participants considered the More time for myself, followed by the Focus on my goals, and the No one dictates my actions, as the most important advantages of being single. Men found the Freedom to flirt around more important than women, while women found the Focus on my goals and the No tensions and fights more important than men. Younger participants rated the Focus on my goals as more important than older ones. Moreover, low scorers in mating performance rated the identified advantages as more important than low scorers.

We predicted that people would find singlehood appealing because it would enable them to develop their strengths. Consistent with this prediction, the Focus on my goals advantage emerged, where participants indicated that, by being single, they could focus on advancing their studies or careers. The More time for myself and the Save resources advantages were also consistent with this argument, as participants indicated that, by being single, they had more resources, such as time available, which they could divert to improving themselves. We have also predicted that people would find singlehood appealing, because it would enable them to engage in many casual relationships. Consistent with this prediction, the Freedom to flirt around advantage emerged, where participants indicated that, by being single, they could flirt with whomever they wanted, and have many sexual partners. Furthermore, we predicted that people would find singlehood appealing because it would enable them to avoid experiencing negative emotions. Accordingly, the Not getting hurt, the Peace of mind, and the No tensions and fights advantages emerged, where participants indicated that, by being single, they would not get hurt by separations, they would not have to worry about their partners cheating on them, there would be no fights with their partners, and they would be less stressed.

There were three more advantages, namely, the No one dictates my actions, the Not do things I dislike, and the Better control of what I eat, which were not predicted by our theoretical framework. These factors can be accounted for by the fact that keeping an intimate relationship requires compromises, as the one party needs to consider and adjust to the needs and wants of the other party. For instance, people need to discuss their actions and choices with their partners, socialize with their partners’ friends and relatives, even if they do not like them, or adjust their eating habits to the ones of their partners. Such adjustments can be taxing for individuals, as they would frequently find themselves doing things they do not like or not doing things they like. Consequently, people may find singlehood appealing as it would enable them not to compromise on what they do or do not do, which can explain the emergence of the aforementioned factors.

Our prediction that men would find singlehood for the purpose of having different casual relationships than women were supported. We also found that women gave significantly higher scores than men to the No tensions and fights advantage. Fights between couples may escalate to physical violence to which women are more vulnerable (Buss, 2000, 2021), which, in turn, would motivate them to avoid such situations, with one way to do so being not to be in an intimate relationship. Moreover, women tend to be more sensitive than men about their weight (Karazsia et al., 2017), which can explain why they rated higher the Better control of what I eat advantage.

Consistent with our original prediction, younger participants rated higher than older ones the Focus on my goals advantage. Moderate to large effects of age were also found for the Not do things I dislike, the No one dictates my actions, and for the More time for myself advantages, with older giving higher scores than younger participants. One possible explanation is that, as people get older, they become more rigid and less willing to make compromises (see also Oh et al., 2021 for further discussion on singlehood and aging). Future research needs to replicate and examine further the causes of the observed age effects.

As we originally predicted, low scorers in mating performance found singlehood more appealing, with the effect being present in eight out of ten advantages, and the effect sizes ranging from moderate to high. This finding suggests that people who want to be in a relationship but face difficulties in doing so may eventually find single more attractive than mated life, so they would give up trying to find a partner. This being the case, a part of voluntary singlehood can be explained by poor mating performance. On the other hand, in terms of mating effort, it could also be the case that people who see single life as attractive would not put much effort into finding a partner. Future research needs to examine further the relationship between poor mating performance, mating effort, and voluntary singlehood.

Singlehood can be appealing to many people, and in the current research, we have identified some of the reasons why this is the case. We expect, however, that there would be considerable individual differences in how people see the identified advantages. We have found sex, age, and mating performance differences, but additional factors are expected to be at play. One such factor is personality. For instance, rigid people who find it difficult to make compromises would tend to find the Not do things I dislike a more important advantage for being single than easygoing people. Another factor is whether one has good chances of attracting casual mates. For example, individuals who are good at flirting, and who have qualities such as good looks that are valued in a short-term mate, may be more likely to see singlehood as appealing in order to be able to flirt around than people who do not score high in these dimensions. More research is required in order to understand how different factors affect the appeal of singlehood.

There has been considerable debate on whether single (DePaulo, 2007; Trimberger, 2006) or mated life (Olds & Schwartz, 2010; Waite & Gallagher, 2001) is better (better in the sense of people being happier and leading a more fulfilling life). The present study has identified some possible advantages of single life, but it certainly does not resolve the debate, as singlehood has evolutionary costs that also need to be systematically examined. Nevertheless, our theoretical framework, and the findings of the present study, can enrich this debate by pointing to the direction that being single can beneficial for limited time periods. In particular, spells of singlehood could be beneficial for enabling individuals to focus on completing their studies or getting a job promotion. Similarly, following the termination of a relationship, a spell of singlehood can enable people to contemplate on what went wrong, and to make improvements and changes to avoid making the same mistakes again. Thus, instead of only asking whether mated or single life is better, we can ask when it is better for an individual to be single and for how long. Considerable more research is necessary however, in order to address such questions. Moreover, the current debate should extend not only to include single versus mated life, but also to take into consideration relationship quality. For instance, Hudson et al. (2020) demonstrated that those in poorer relationships were similar in well-being to those who were single.

One limitation of the current research is that it was based on non-probability samples, so our findings may not readily generalize to the population. Moreover, we employed self-report instruments, which are subject to different biases, including inaccurate answers. In addition, several factors that the current research has not measured, such as relationship experience and personality, are likely to predict how people view the benefits of singlehood. Moving on, although the items of the instrument assessing mating performance did not distinguish between long-term and casual relationship (e.g., “I find it easy to start a romantic relationship”), participants may have interpret them to refer to long-term relationships. In effect, the current instrument may not have adequately captured the mating success of individuals who employed a short-mating strategy. Thus, future research may attempt to replicate our findings using different instruments that distinguish between success in casual and long-term intimate relationships.

Furthermore, cultural factors are likely to affect the appeal of singlehood. For instance, in cultures where marriages are arranged, people may see singlehood as a way to escape from an undesirable union. Similarly, in more individualistic cultures, singlehood may be more appealing to people as a way to avoid compromises and do what they wish. Specifically, in the Greek cultural context, family is valued and it is common for parents to attempt to motivate their single adult children to find an intimate partner. These attempts intensify as children become older. Such social pressure may turn singlehood less appealing. On the other hand, the ongoing financial crisis in Greece and in the republic of Cyprus, along with inadequate social provisions in the domains of health and education, make raising children a difficult endeavor. Such difficulties may turn singlehood more appealing as a way to avoid the burden of having to raise a family. Future cross-cultural studies could attempt to examine how cultural factors can affect the appeal of singlehood.

Singlehood is a complex phenomenon that has become increasingly common in contemporary societies. In the current research, we have identified 10 broader advantages of being single. Considerable more work is required however, in order to understand better what people find appealing in single life.

Availability of Data and Materials

All data are available on request by the first author.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Adams, M. (1976). Single blessedness: Observations on the single status in married society. Basic Books.

Apostolou, M. (2015). Past, present, and why people struggle to establish and maintain intimate relationships. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 9, 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000052

Apostolou, M. (2017). Why people stay single: An evolutionary perspective. Personality and Individual Differences, 111, 263–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.034

Apostolou, M. (2019). Why men stay single: Evidence from Reddit. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 5, 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-018-0163-7

Apostolou, M., Birkás, B., da Silva, C. S. A., Esposito, G., Hsu, R. M. C. S., Jonason, P. K., Karamanidis, K., & O, J., Ohtsubo, Y., Putz, Á., Sznycer, D., Thomas, A. G., Valentova, J. V., Varella, M. A. C., Kleisner, K., Flegr, J., & Wang, Y. (2021). Reasons of singles for being single: Evidence from Brazil. China, Czech Republic, Greece, Hungary, India, Japan and the UK. https://doi.org/10.1177/10693971211021816

Apostolou, M., Shialos, M., & Georgiadou, P. (2019). The emotional cost of poor mating performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 138, 188–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.10.003

Apostolou, M., Shialos, M., Kyrou, E., Demetriou, A., & Papamichael, A. (2018). The challenge of starting and keeping a relationship: Prevalence rates and predictors of poor mating performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 122, 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.004

Apostolou, M., & Wang, Y. (2019). The association between mating performance, marital status, and the length of singlehood: Evidence from Greece and China. Evolutionary Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474704919887706

Arnqvist, G., & Rowe, L. (2005). Sexual conflict. Princeton University Press.

Brown, A. (2020). Nearly half of U.S. adults say dating has gotten harder for most people in the last 10 years. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/08/20/nearly-half-of-u-s-adults-saydating-has-gotten-harder-for-most-people-in-the-last-10-years/

Buss, D. M. (2000). The dangerous passion: Why jealousy is as necessary as love and sex. The Free Press.

Buss, D. M. (2016). The evolution of desire: Strategies of human mating (4th ed.). Basic Books.

Buss, D. M. (2017). Sexual conflict in human mating. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 24(4), 307–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0963721417695559

Buss, D. M. (2021). When men behave badly: The hidden roots of sexual deception, harassment, and assault. Little, Brown Sparks.

Buss, D. M., Goetz, C., Duntley, J. D., Asao, K., & Conroy-Beam, D. (2017). The mate switching hypothesis. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 143–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.07.022

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100(2), 204–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.2.204

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (2016). Sexual strategies theory. In T. K. Shackelford & V. A. Weekes-Shackelford (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer International Publishing.

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (2019). Mate preferences and their behavioral manifestations. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 77–110. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103408

Cherlin, A. J. (2009). The marriage-go-round. Knopf.

DePaulo, B. (2007). Singled out: How singles are stereotyped, stigmatized, and ignored, and still live happily ever after. Martin’s Press.

Dixson, A. F. (2009). Sexual selection and the origins of human mating systems. Oxford University Press.

Gangestad, S. W., & Simpson, J. A. (2000). The evolution of human mating: Trade-offs and strategic pluralism. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23, 573–644. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0000337X

Hudson, N. W., Lucas, R. E., & Donnellan, M. B. (2020). Are we happier with others? An investigation of the links between spending time with others and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(3), 672–694. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000290

Karazsia, B. T., Murnen, S. K., & Tylka, T. L. (2017). Is body dissatisfaction changing across time a cross-temporal meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 143, 293–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000081

Kim, P. S., James, E., Coxworth, J. E., & Hawkes, K. (2012). Increased longevity evolves from grandmothering. Proceeding of the Royal Society B, 279, 4880–4884. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.1751

Klinenberg, E. (2012). Going solo: The extraordinary rise and surprising appeal of living alone. Duckworth Overlook.

Meltzer, A. L., Novak, S. A., McNulty, J. K., Butler, E. A., & Karney, B. R. (2013). Marital satisfaction predicts weight gain in early marriage. Health Psychology, 32(7), 824–827. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031593

Nomaguchi, K. M., & Bianchi, S. M. (2004). Exercise time: Gender differences in the effects of marriage, parenthood, and employment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66(2), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2004.00029.x

Oh, J., Chopik, W. J., & Lucas, R. E. (2021). Happiness singled out: Bidirectional associations between singlehood and life satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211049049

Olds, J. & Schwartz, R. S. (2010). The lonely American: Drifting apart in the twenty-first century. Beacon Press.

Ortiz-Ospina, E. (2019). The rise of living alone: How one-person households are becoming increasingly common around the world. Our World in Data. https://ourworldindata.org/livingalone

Sarkisian, N., & Gerstel, N. (2016). Does singlehood isolate or integrate? Examining the link between marital status and ties to kin, friends, and neighbors. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 33(3), 361–384. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407515597564

Shackelford, T. K., & Goetz, A. T. (2012). The Oxford handbook of sexual conflict in humans. Oxford University Press.

Symons, D. (1979). The evolution of human sexuality. Oxford University Press.

Tang, J., Galbraith, N., & Truong, J. (2019). Living alone in Canada (CS75–006/2019–3E-PDF). Retrieved from http://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2019/statcan/75-006-x/75-006-2019-3-eng.pdf

Thomas, A. G., Jonason, P. K., Blackburn, J., Kennair, L. E. O., Lowe, R., Malouff, J., & Li, N. P. (2020). Mate preference priorities in the East and West: A cross-cultural test of the mate preference priority model. Journal of Personality, 88(3), 606–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12514

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (2008). The evolutionary psychology of the emotions and their relationship to internal regulatory variables. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Johnes, & L. F. Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (3rd ed., pp. 114–137). Guilford.

Trimberger, K. E. (2006). The new single women. Beacon Press.

Waite, L., & Gallagher, M. (2001). The case for marriage. Broadway Books.

Walter, K. V., Conroy-Beam, D., Buss, D. M., Asao, K., Sorokowska, A., Sorokowski, P., Zupančič, M. (2020). Sex differences in mate preferences across 45 countries: A large-scale replication. Psychological Science, 31(4), 408–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620904154

Wang, W., & Parker, K. (2014). Record share of Americans have never married. Pew Research Center’s Social & Demographic Trends Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors (Menelaos Apostolou and Chistoforos Christoforou) contributed to the conception and design of the study as well as to material preparation, data collection, and analysis. The manuscript was written by Menelaos Apostolou. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The current research received ethics approval from the Department of Social Sciences Ethics Committee.

Consent to Participate

Consent was asked from all participants prior to participation.

Consent for Publication

The authors grant the publisher permission to publish this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Apostolou, M., Christoforou, C. What Makes Single Life Attractive: an Explorative Examination of the Advantages of Singlehood. Evolutionary Psychological Science 8, 403–412 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-022-00340-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-022-00340-1