Abstract

Evidence from the anthropological and historical records indicates that, in contemporary and ancestral preindustrial societies, mate choice is regulated with parents choosing spouses for their children. On the basis of this evidence, it has been argued that most of human evolution took place in a context where individuals had limited space in which to exercise choice. Nevertheless, even in this context, mate choice can still be exercised. Using evidence from the Standard Cross-Cultural Sample, the current study found that, in an arranged marriage setting, there is a considerable space for individuals to exercise mate choice in premarital relationships, in extramarital relationships, and in forced sex or rape. These patterns do not vary considerably between societies of different subsistence types. However, premarital relationships were less common and rape was more common in societies where arranged marriage was the dominant mode of long-term mating. The evolutionary implications of these findings are further discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

A key premise of evolutionary psychology and associate disciplines is that psychological mechanisms constitute the product of evolutionary processes that took place in ancestral human societies (Barkow et al. 1990). As a consequence, the nature and function of these mechanisms can be understood in reference to the ancestral and, not necessarily, to the modern human condition (Tooby and Cosmides 1990). Surprisingly, however, much of the scholarly work in the field fails to take into consideration the ancestral human condition or erroneously assumes that certain aspects of the contemporary reflect also the ancestral human condition (Apostolou 2014a, b).

This failure can be particularly observed for the domain of mating, a main area of investigation in evolutionary psychology: Some scholars assume that, in ancestral human societies, similar to the contemporary postindustrial societies, individuals were free to choose their own mates (e.g., Miller 2000). However, anthropological, historical, archeological, and physiological evidence indicates that this assumption is not sound. In particular, this evidence points toward the direction that mate choice was regulated, with parents choosing spouses for their children and not the children for themselves (Apostolou 2007, 2014b; Broude and Greene 1976). It also points toward the direction that male-male competition, where men fight other men to monopolize access to women, was strong in ancestral human societies (Puts 2010, 2016).

Starting from the latter, where male-male competition is strong, traits such as robust muscles, large body size, and aggression that enable men to fight other men effectively are selected and increase in frequency in the population. The observed dimorphism in contemporary populations, where men are on average physically stronger, taller, and more aggressive than women, suggests that they came from ancestral populations where male-male competition had been strong (Puts 2010, 2016).

Moving on to the regulation of mating, for several decades, it has been known to anthropologists that in preindustrial societies, parents exercise considerable influence over their children’s mating decisions (Broude and Greene 1976; Stephens 1963). This influence is manifested predominantly in the institution of arranged marriage. In a typical arranged marriage society, parents find spouses for their children in negotiation with other parents (Apostolou 2013a). An analysis of the patterns of mating in preindustrial societies that based their subsistence on hunting and gathering found that the most common mode of long-term mating was arranged marriage (Apostolou 2007). Similarly, a different study found that arranged marriage was the most common mode of marriage in preindustrial societies that based their subsistence on agriculture and animal husbandry (Apostolou 2010).

Contemporary preindustrial societies (i.e., societies studied by anthropologist in the nineteenth and twentieth century, which based their subsistence on hunting and gathering or on agriculture and domestication of animals) are likely to resemble ancestral ones (Lee and Devore 1968). For instance, if marriage in contemporary hunting and gathering societies is based on free courtship, which is found only in small minority of societies, it is reasonable to assume that this was also the case in ancestral human societies which based their subsistence on hunting and gathering. To put it differently, in the light of this evidence, it is unlikely that, in ancestral societies, it would be typical for individuals to choose their own spouses. On the basis of this reasoning, as the typical mode of long-term mating in contemporary preindustrial societies is arranged marriage, it can be argued that this pattern was also typical in ancestral human societies (Apostolou 2014a).

Ancestral hunting and gathering societies did not leave behind written records, but phylogenetic analysis, which attempts to reconstruct ancestral human condition, found support for the hypothesis that arranged marriage was also typical of these societies (Walker et al. 2011). On the other hand, ancestral societies that based their subsistence on agriculture and animal husbandry left behind written records which indicate that they practiced arranged marriage. In particular, Apostolou (2012) examined the historical records of 16 such societies, and found than in 15 of them, arranged marriage was the typical mode of long-term mating, whereas in one society the historical evidence was inconclusive.

Furthermore, it needs to be said that anthropological and historical evidence indicates that raids and wars, motivated by the gaining of resources, one being women, are frequent in preindustrial societies (Ember and Ember 1992; Keeley 1996). However, these records indicate also that most of the human mating takes place in times of peace, in the institutions of marriage. Accordingly, it is reasonable to argue that this was also the case in ancestral human societies (Apostolou 2014a).

Overall, there are good reasons to believe that, in the ancestral context, freedom to exercise choice had been constrained by male-male competition and predominantly by parental control over mating. However, there are also good reasons to believe that even under these constraints, individuals had considerable space in which to exercise choice. In more detail, individuals can exercise mate choice prior to marriage by escaping their parents’ control and establishing premarital relationships with mates of their choice. Individuals can also choose to stay married with individuals their parents have selected for them and establish extramarital relationships with mates of their own choice.

Men may follow a forced-sex mating strategy in order to circumvent individual or parental choice (Apostolou 2013b; Thornhill and Palmer 2000). Rape is found across preindustrial and postindustrial societies (Roze-Koker 1987), and it provides a way for individuals to exercise choice outside parental control. For instance, if a forced-sex strategy in a given context has few costs, men can target women of their choice and force sex on them. Therefore, the current study aims to examine also the prevalence rate of rape in arranged marriage societies.

Overall, the current study aims to test the hypothesis that, in a preindustrial context where arranged marriage is prevalent, individuals have space in which to exercise mate choice, through premarital and extramarital relationships and rape.

Method

Procedures

For the purpose of this research, the Standard Cross-cultural Sample (SCCS) which consists of 186 preindustrial societies was employed. The use of the SCCS has several advantages, including a well-described set of societies which are relatively independent from each other (Murdock and White 1969). In addition, coded variables on prevalence rates for rape and premarital and extramarital relationships are available for this sample.

Measures

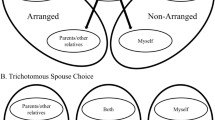

We employed several variables in order to examine the prevalence rates as well as the attitudes toward rape and premarital and extramarital relationships. These variables, and their associated identification numbers in the SCCS, are listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3. In order to classify societies according to marriage type, a variable with four levels was used. The variable was constructed by Apostolou (2010) on the basis of another variable with more levels from the SCCS. This variable refers to arranged marriage for women and has the following levels: “parental arrangement,” “courtship subject to parental approval,” “courtship,” and “parental arrangement-courtship.” In parental arrangement, parents arrange the marriages of their children; in courtship subject to parental approval, individuals find their own mates but their choices are subject to their parents approval; in courtship, individuals find their own mates with little influence from their parents; and finally, in the arrangement-courtship, marriages based on parental arrangement or free choice are practiced in roughly equal frequencies.

Parental control over mating is focused predominantly on daughters (Apostolou 2014b), so this variable is more informative about the prevalence of arranged marriage in a given society than the respective variable on male marriage. On the basis of this variable, societies were classified in two categories, namely “arranged marriage,” where arranged marriage was the dominant mode of marriages, and “other,” where it was not. Finally, with respect to subsistence type, we employed Apostolou’s (2011) classification to group societies into those that based their subsistence predominantly on agriculture and animal husbandry and those that based their subsistence predominantly on hunting and gathering.

Results

Premarital Relationships

Although we did not have specific hypotheses in mind, it is likely that there may be significant differences in the space that individuals have in which to exercise choice through premarital and extramarital relationships between societies where arranged marriage is prevalent and societies where it is not. For instance, we expect that parents would strengthen their control over their unmarried children, reducing in effect the prevalence rate of premarital relationships. Similarly, subsistence type may also affect the space in which individuals exercise choice. For instance, agropastoral societies are larger than foraging ones; thus, men who follow a forced-sex mating strategy are less likely to be detected in the former than in the latter. This difference is expected to have an effect on how frequently men would choose to follow this strategy. Accordingly, we will attempt to investigate also whether there are significant marriage and subsistence type effects.

Starting from premarital relationships, from Table 1, we can see that in about half of the societies in the sample, these relationships were “Universal”; however, in arranged marriage societies, premarital relationships were Universal in 27% of the cases. In order to examine whether there were significant subsistence and marriage type effects, multinomial logistic regression was performed, where the frequency of premarital relationships was entered as the dependent variable, and marriage type and subsistence type were entered as the independent variables.

The results indicated that there was no significant effect of the subsistence type, but there was a significant effect of marriage type [χ 2(3, N = 94) = 18.32, p < .001]. The odds ratio indicated that arranged married societies were 5.5 times more likely to classify as having premarital relationships “Occasional” and 9.9 times more likely to classify as having premarital relationships “Uncommon” than “Universal,” as opposed to the rest of the societies. They were also 1.5 times more likely to classify as “Moderate” than “Universal,” but as indicated by the Wald statistic, this odds ratio was not significant.

Moving on to the next variable which examined the prevalence of premarital relationships for men, from Table 1, we can see that, in about 60% of the societies in the sample, these relationships were “Universal,” with the respective rate in arranged marriage societies to be about 39%. In order to examine whether there were significant subsistence and marriage type effects, multinomial logistic regression was performed, where the frequency of premarital relationships was entered as the dependent variable, and marriage type and subsistence were entered as the independent variables.

The results indicated that there was no significant effect of the subsistence type, but there was a significant effect of marriage type [χ 2(3, N = 89) = 8.38, p = .039]. There was only one significant odds ratio which indicated that arranged married societies, as opposed to the rest of the societies, were 5.9 times more likely to classify as having “Uncommon” than “Universal” premarital relationships.

Next, we examined attitudes toward women’s premarital relationships. Table 1 shows that, in about 44% of the societies, premarital relationships were expected or tolerated, and in about 27% of the societies, they were strongly disapproved. On the other hand, in arranged marriage societies of about 23% of the cases, premarital relationships were expected or tolerated, and in about 47%, they were strongly disapproved.

In order to examine whether there were significant subsistence and marriage type effects, multinomial logistic regression was performed, where the tolerance of premarital relationships was entered as the dependent variable and marriage type and subsistence type were entered as the independent variables. As the dependent variable had many categories, there were too few cases in each cell, and as a consequence, the model could not be fitted. In order to overcome this issue, we collapsed the dependent variable into fewer categories. The categories “Expected,” “Tolerated,” and “Mildly disapproved” were collapsed to one category, namely “Tolerated or mildly disapproved,” and the “Disallowed” and “Strongly disapproved” were merged into “Strongly disapproved or disallowed.” Using this method, the model could be fitted. There was no significant effect of subsistence type, but there was a significant effect of marriage type [χ 2(2, N = 111) = 28.35, p < .001]. There was only one significant odds ratio which indicated that arranged marriage societies, as opposed to the rest of the societies, were 12.1 times more likely to classify as “Strongly disapproved or disallowed” than as “Tolerated or mildly disapproved.”

This dataset did not code for attitudes toward premarital relationships of men. However, another variable provided evidence on whether there was a double standard with regard to premarital sex. As we can see from Table 1, for slightly less than half of the societies in the sample, there was a double standard where the premarital relationships of men were more tolerated than the premarital relationships of women. On the other hand, in arranged marriage societies, the double standard was found in more than 60% of the societies.

In order to examine whether there were significant subsistence and marriage type effects, multinomial logistic regression was performed, where the double standard variable was entered as the dependent variable, and marriage type and subsistence were entered as the independent variables. The results indicated that there was no significant effect of the subsistence type, but there was a significant effect of marriage type [χ 2(1, N = 58) = 6.65, p = .010]. The odds ratio indicated that arranged married societies, as opposed the rest of the societies, were 4.3 times more likely to classify as “Yes” than “No, equal restrictions on male and female.”

Extramarital Relationships

We can now proceed to examine the prevalence rate of extramarital relationships for married women. As we can see from Table 2, in about half of the societies in the sample, extramarital relationships were uncommon or occasional. Similar rates were found for the arranged marriage societies. With respect to the frequency of extramarital relationships of married men, in about 30% of the societies, extramarital relationships were uncommon or occasional, with the respective rate in arranged marriage societies being about 42%.

In order to examine whether there were significant subsistence and marriage type effects, multinomial logistic regression was performed, where the frequency of extramarital relationships was entered as the dependent variable and marriage type and subsistence type were entered as the independent variables. This analysis was performed twice, once for women and once for men. No significant effects were produced.

We have also used evidence from a different study (Whyte 1978) which coded however only for the frequency of extramarital relationships of married women. As we can see from Table 2, in about half of the societies, such relationships were reported as uncommon and in about half of the societies as common. Similar prevalence rates were found in arranged marriage societies. As above, in order to examine whether there were significant subsistence and marriage type effects, multinomial logistic regression was performed, where the frequency of extramarital relationships was entered as the dependent variable and marriage type and subsistence type were entered as the independent variables. No significant effects were produced.

Finally, we would like to examine whether there was a double standard, where the extramarital relationships were punished differently for men and for women. In Table 2, we can see that, in about 43% of the societies in the sample, women were punished more than men, while in about half of the societies the punishment was similar for both sexes. There were only two societies in the sample where punishment was more severe for men than it was for women. We can see also that in arranged marriage societies, the double standard favoring men was higher in frequency.

In order to examine whether there were significant subsistence and marriage type effects, multinomial logistic regression was performed, where the double standard variable was entered as the dependent variable and marriage type and subsistence type were entered as the independent variables. The results indicated that there was no significant effect of the subsistence type, but there was a significant effect of marriage type [χ 2(1, N = 57) = 7.81, p = .005]. The odds ratio indicated that the arranged married societies were 7.1 times more likely to classify as “Yes” than as “No, equal restrictions on male and female,” as opposed the rest of the societies.

Rape

We can move on to examine the prevalence rate for rape. As we can see from Table 3, in about 60% of societies, rape is either absent or rare, with the respective rating in arranged marriage societies to be about 30%. In order to examine whether there were significant subsistence and marriage type effects, multinomial logistic regression was performed, where the prevalence of rape was entered as the dependent variable, and marriage type and subsistence were entered as the independent variables.

The model could not be fitted because there were few observations in each category. To address this problem, we collapsed the “Absent” and “Rare” categories into a single category “Absent or Rare.” This way, the model could be fitted. The results indicated that there was no significant effect of the subsistence type, but there was instead a significant effect of marriage type [χ 2(2, N = 26) = 7.89, p = .005]. The odds ratio indicated that arranged married societies were 14 times more likely to classify as “Common” than “Absent or Rare,” as opposed to the rest of the societies.

We can move on to investigate attitudes toward rape for the same set of societies. From Table 3, we can see that in about 46% of the societies, rape was strongly disapproved, and in about 23%, it was accepted or ignored. These prevalence rates were similar for the arranged marriage societies. As above, in order to examine whether there were significant subsistence and marriage type effects, multinomial logistic regression was performed, where the approval of rape was entered as the dependent variable and marriage type and subsistence type were entered as the independent variables. The results indicated that there was a significant effect of subsistence type [χ 2(3, N = 31) = 7.79, p = .051]. There was only one significant odds ratio which indicated that agropastoral, as opposed to foraging societies, were 14.1 times more likely to classify as “Strongly disapproved” than as “Accepted/Ignored.”

Discussion

The evidence presented in the current study indicates that, in the vast majority of arranged marriage societies, premarital and extramarital relationships and rape are present. Thus, the first conclusion that we can reach is that, even where mate choice is regulated, individuals have space in which to exercise mate choice. The evidence indicates further that the prevalence rates are high in preindustrial societies, in general, and in arranged marriage societies, in particular. Thus, the second conclusion we can reach is that individuals have substantial space in which to exercise choice through these means.

It is difficult, however, to estimate precisely the size of this space, but it is reasonable to say that it is not considerable enough to neutralize parental control over mating. If factors such as premarital and extramarital relationships would completely undermine parental control over mating, then arranged marriage would be pointless, and it would not be practiced. The fact that it is practiced suggests that these factors are not enough to undermine parental control over mating.

One reason is that parents can take measures to safeguard them from possible threats to their power to control mate choice. To begin with, they arrange the marriages of their children when the latter are young so as to decrease the window of opportunity for them to exercise mate choice prior to marriage (Apostolou 2014b). Thus, individuals cannot engage in many premarital relationships because they do not have sufficient time to do so. Accordingly, a possible interpretation of the current findings is that many individuals have few premarital relationships, and not that many individuals have many premarital relationships. Also, young women who engage in premarital relationships may not be sexually mature enough to become pregnant, while young men who engage in premarital relationships frequently do so with older women, who are widows and less controlled by their family, but who are also likely to have entered menopause (Apostolou 2014b). These factors may turn premarital sex inconsequential; however, even if pregnancy occurs, infanticide is practiced to reduce its consequences (Frayser 1985; Liddle et al. 2012).

Furthermore, parents frequently chaperone their unmarried children in order to drive away possible suitors and reduce opportunities for premarital sex (Anderson et al. 1992; Apostolou 2013a). In addition, many preindustrial societies practice segregation of sexes in order to reduce contact between men and women and, thus, the opportunities to engage in premarital relationships (Apostolou 2013a; Divale et al. 1998). These factors possibly explain why premarital relationships are significantly less prevalent in arranged marriage-societies than in the rest of the societies. In the former, these relationships can undermine parents’ capacity to arrange a profitable marriage; therefore, parents use different means to prevent their children from engaging in them which results in fewer instances of premarital relationships. In the latter societies, premarital relationships do not undermine parents’ authority to arrange marriage, as marriages are usually not arranged, so parents are less motivated to do so which results in more instances of premarital relationships.

In extramarital relationships, parents have little direct influence. Even so, extramarital relationships involve risks such as divorce, social stigmatization, and severe punishment, which may involve body mutilation or even death (Apostolou 2014b). These factors limit the space that individuals have in which to exercise choice through extramarital relationships. In addition, the double standard, where it is more acceptable for men than for women to engage in such relationships, indicates that this space is smaller for women than it is for men.

Finally, rape is one way for men to exercise choice independently of their parents’ will. As rape can considerably undermine parental control over mating, parents take measures to prevent their daughters from being exposed to this danger, including chaperoning and segregation of sexes discussed above (Apostolou 2013b). It is surprising then that rape was found to be significantly more prevalent in the arranged marriage than in the rest of the societies. One possibility is that this result was due to sampling error; for instance, we only have 11 observations for the arranged marriage societies. Therefore, replication is needed to draw more reliable conclusions on this phenomenon. Another possibility is that, in societies where mate choice is not regulated, men can more readily engage in casual relationships with women than in arranged marriage societies where, due to parental control, there are fewer women available for casual mating. In turn, such shortage may motivate several men to adopt a forced-sex strategy in order to satisfy their sexual urges.

Despite the various constraints, individuals in arranged marriage preindustrial societies have space in which to exercise choice through these different means. Since ancestral preindustrial societies are likely to resemble contemporary ones (Lee and Devore 1968), it is reasonable to assume that similar patterns of mating were also found in the former. Accordingly, individual mate choice has been a strong selection force during the largest period of human evolution. As such, it should have played a significant role in shaping adaptations which relate to mating.

In addition, individual mate choice would have shaped adaptations to enable individuals to attract and retain opposite-sex partners in the ancestral, and not in the contemporary, context. As a consequence, if the way individual mate choice had been exercised in the ancestral environment was different from the way it is exercised in the modern environment, these adaptations may not work well in the modern environment. For instance, the evidence presented here indicates that rape is considerably more tolerated in preindustrial societies than in postindustrial societies. If rape was also considerably tolerated in ancestral human societies, selection pressures would have been exercised on men to evolve mechanisms that would enable them to follow this strategy successfully. As a consequence, men today may be predisposed toward using a forced-sex strategy more than it is optimal for modern conditions, i.e., this strategy is more likely to lead them to jail than to increased reproductive success.

Overall, in ancestral human societies, individuals had space in which to exercise choice, and the transition to postindustrialism had a quantitative as well as a qualitative effect on this space. It increased it considerably, but it has also changed the way people exercise mate choice. In turn, people may lack the adaptations, or they may not have optimal adaptations to address the demands of mating in modern conditions.

One advantage of this research is that it is based on anthropological observations on actual patterns of mating rather than on responses to hypothetical questions. Another benefit is that the data we employed were not collected with the specific hypothesis of the current study in mind, and so, they are free from our biases. There are limitations however, with the most important one being that the variables employed are of sensitive nature. Therefore, even after careful investigation, the anthropologists may not be able to provide the true estimates. More specifically, premarital and extramarital relationships are associated with punishment and social stigma. Accordingly, individuals engage in them in secrecy and would be reluctant to report them. This is also the case with rape, so individuals may be reluctant to report that they had actually committed or that they had been victims of rape. Thus, the estimates we have produced in the current study may constitute underreports.

Overreporting is also likely. For instance, unmarried men may exaggerate the number of intimate relationships they had with married women in order to demonstrate their vigor. In addition, women who had illegitimate consensual relationships with men may report that they were forced to them in order to avoid social consequences, which may be more severe than the social consequences of rape. However, in both extramarital and rape cases, we expect the underreporting bias to be stronger than the overreporting bias.

Furthermore, for certain variables, the number of observations was limited, so testing statistical significance and reaching general conclusions was problematic. Last, individuals can also exercise choice through elopement and through manipulating their parents (Apostolou 2014b). To our knowledge, there are no codes for these variables for the SCCS, so they were not included in our analysis. Future anthropological work needs to be directed toward coding such variables.

Overall, the ancestral human condition needs to be taken into consideration if valid theories on the evolutionary origin and function of behavioral mechanisms are to be made. The current evidence indicates that, even where parental control over mating dominates, individual mate choice is a strong sexual selection force that is exercised in forced sex and premarital and extramarital relationships. This force had then an important role in shaping adaptations related to mate choice that future studies need to investigate.

References

Anderson, J. L., Crawford, C. B., Nadeau, J., & Lindberg, T. (1992). Was the duchess of Windsor right? A cross-cultural review of the socioecology of ideals of female body shape. Ethology and Sociobiology, 13, 197–227.

Apostolou, M. (2007). Sexual selection under parental choice: the role of parents in the evolution of human mating. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28, 403–409.

Apostolou, M. (2010). Sexual selection under parental choice in agropastoral societies. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31, 39–47.

Apostolou, M. (2011). Inheritance as an instrument of parental control over mating. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 28, 374–382.

Apostolou, M. (2012). Sexual selection under parental choice: evidence from sixteen historical societies. Evolutionary Psychology, 10, 504–518.

Apostolou, M. (2013a). Parent-offspring conflict over mating and the evolution of mating-control institutions. Mankind Quarterly, 54, 49–74.

Apostolou, M. (2013b). The evolution of rape: the fitness benefits and costs of a forced-sex mating strategy in an evolutionary context. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 18, 484–490.

Apostolou, M. (2014a). Sexual selection in ancestral human societies: the importance of the anthropological and historical records. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 8, 86–95.

Apostolou, M. (2014b). Sexual selection under parental choice: the evolution of human mating behaviour. Hove: Psychology Press.

Barkow, J., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (1990). The adapted mind: evolutionary psychology and the generations of culture. New York: Oxford University Press.

Broude, G., & Greene, S. J. (1976). Cross-cultural codes on twenty sexual attitudes and practices. Ethnology, 15, 409–429.

Divale, W., Abrams, N., Barzola, J., Harris, E., & Henry, F. M. (1998). Sleeping arrangements of children and adolescents: SCCS sample codes. World Cultures, 9, 3–12.

Ember, C. R., & Ember, M. (1992). Codebook for “Warfare, aggression, and resource problems: cross-cultural codes”. Behavior Science Research, 26, 169–186.

Frayser, S. G. (1985). Varieties of sexual experience. New Heaven: HRAF Press.

Keeley, L. (1996). War before civilization. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lee, R. B., & Devore, I. (1968). Man the hunter. New York: Aldine.

Liddle, J. R., Shackelford, T. K., & Weekes-Shackelford, V. A. (2012). Why can’t we all just get along? Evolutionary perspectives on violence, homicide, and war. Review of General Psychology, 16, 24–36.

Miller, G. (2000). The mating mind. London: BCA.

Murdock, G. P., & White, D. R. (1969). Standard cross-cultural sample. Ethnology, 8, 329–369.

Puts, D. A. (2010). Beauty and the beast: mechanisms of sexual selection in humans. Evolution and Human Behavior, 31, 157–175.

Puts, D. A. (2016). Human sexual selection. Current Opinion in Psychology, 7, 28–32.

Roze-Koker, P. D. (1987). Cross-cultural codes on seven types of rape. Behavior Science Research, 21, 101–117.

Stephens, W. N. (1963). The family in cross-cultural perspective. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Thornhill, R., & Palmer, C. T. (2000). A natural history of rape: biological bases of sexual coercion. Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Tooby, J., & Cosmides, L. (1990). The past explains the present. Ethology and Sociobiology, 11, 375–424.

Walker, R. S., Hill, K. R., Flinn, M. V., & Ellsworth, R. M. (2011). Evolutionary history of hunter-gatherer marriage practices. PLoS ONE, 6, e19066.

Whyte, M. K. (1978). Cross-cultural codes dealing with the relative status of women. Ethnology, 17, 211–237.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank Georgia Kapitsaki and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive feedback which enabled the improvement of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Apostolou, M. Individual Mate Choice in an Arranged Marriage Context: Evidence from the Standard Cross-cultural Sample. Evolutionary Psychological Science 3, 193–200 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-017-0085-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40806-017-0085-9