Abstract

Aims

The objective of this study is to investigate the association between multiple antihypertensive use and mortality in residents with diagnosed hypertension, and whether dementia and frailty modify this association.

Methods

This is a two-year prospective cohort study of 239 residents with diagnosed hypertension receiving antihypertensive therapy across six residential aged care services in South Australia. Data were obtained from electronic medical records, medication charts and validated assessments. The primary outcome was all-cause mortality and the secondary outcome was cardiovascular-related hospitalizations. Inverse probability weighted Cox models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all-cause mortality. Covariates included age, sex, dementia severity, frailty status, Charlson’s comorbidity index and cardiovascular comorbidities.

Results

The study sample (mean age of 88.1 ± 6.3 years; 79% female) included 70 (29.3%) residents using one antihypertensive and 169 (70.7%) residents using multiple antihypertensives. The crude incidence rates for death were higher in residents using multiple antihypertensives compared with residents using monotherapy (251 and 173/1000 person-years, respectively). After weighting, residents who used multiple antihypertensives had a greater risk of mortality compared with monotherapy (HR 1.40, 95%CI 1.03–1.92). After stratifying by dementia diagnosis and frailty status, the risk only remained significant in residents with diagnosed dementia (HR 1.91, 95%CI 1.20–3.04) and who were most frail (HR 2.52, 95%CI 1.13–5.64). Rate of cardiovascular-related hospitalizations did not differ among residents using multiple compared to monotherapy (rate ratio 0.73, 95%CI 0.32–1.67).

Conclusions

Multiple antihypertensive use is associated with an increased risk of mortality in residents with diagnosed hypertension, particularly in residents with dementia and among those who are most frail.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The risk-to-benefit ratio for treating hypertension in older people is widely debated. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that treatment to at least current guideline standards for blood pressure (BP) (< 150/90 mmHg) substantially improves cardiovascular and mortality outcomes in older adults [1]. However, there is less consistent evidence that lower BP targets are beneficial for high-risk patients or residents of aged care services. The American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association recommend prescribing as few antihypertensives as possible to achieve BP goals [2,3,4]. Older people are at the highest risk of ischemic events due to loss of baroreceptor sensitivity, sympathetic nervous system responsiveness and cerebral autoregulation [3].

Studies suggest J-shaped or U-shaped associations between BP and mortality [5]. Several studies show that high BP (> 150/90 mmHg) increases mortality, similar to the younger population [6,7,8], while other studies have shown a relationship between low BP (< 140/70 mmHg) and increased mortality in older people [9]. The systolic blood pressure intervention trial (SPRINT) compared intensive blood pressure treatment (BP < 120 mmHg) to standard treatment (BP < 140 mmHg) in patients aged 75 years and older. Intensive treatment was associated with a 33% relative risk reduction in cardiovascular events and 32% reduction in total mortality [10]. The hypertension in the very elderly trial (HYVET) study, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of people aged ≥ 80 years, reported that antihypertensive treatment reduced non-fatal and fatal stroke, cardiovascular and all-cause mortality [11]. However, both SPRINT and HYVET excluded residents of aged care services.

Between 50% and 70% of general patients will not achieve BP goals with monotherapy alone [12]. A meta-analysis of 42 trials found that in general adults, combining antihypertensives from different classes was approximately five times more effective in lowering BP than increasing the dose of a single medication. However, the evidence for treating older people with multiple antihypertensives is limited [13]. Older people are susceptible to orthostatic hypotension, and subsequent adverse events including syncope, falls, fractures, cognitive impairment and cardiovascular difficulties [14, 15]. In addition, there is evidence that the relationship between BP levels and mortality depends on functional and cognitive status in older adults [16, 17]. The criteria to assess appropriate medication use among elderly complex patients (CRIME) discourage multiple antihypertensive use in older people with limited life expectancy, functional and cognitive impairment [18].

Residents of aged care services have a high prevalence of frailty, cognitive impairment and multimorbidity, and are often excluded from clinical trials. This has led to a paucity of information on prescribing risks and benefits in this setting [1]. Neither the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) nor the Australian Heart Foundation provide specific guidelines for the management of hypertension in aged care services, or in people with dementia or frailty. This is problematic because antihypertensive medications may have a different risk-to-benefit ratio in people with dementia and frailty [19]. Furthermore, systematic reviews have reported that frailty and dementia are common in people with hypertension [20, 21], and there is a strong association between multiple medication use and these conditions [22]. The predictive values of blood pressure and arterial stiffness in institutionalized very aged population (PARTAGE) study of European residents aged over 80 years found that those with low systolic blood pressure (SBP) (< 130 mmHg) who received multiple antihypertensive therapy had a greater than twofold increased risk of mortality over 2 years [23].

The objective of our study was to investigate the association between multiple antihypertensive use and mortality in residents of aged care services with diagnosed hypertension, and whether dementia and frailty modify this association.

Methods

Design and setting

This was a secondary analysis of data collected in a prospective cohort study of residents from six metropolitan and regional aged care services in South Australia. Aged care services are synonymous with nursing homes and long-term care facilities and provide supported accommodation to people with care needs that can no longer be met in their own homes [24]. People with dementia and frailty comprise up to 52% and 73% of permanent residents of aged care services, respectively [25, 26]. Baseline data were collected between April and August 2014. The full study protocol has been described previously [27].

Study sample

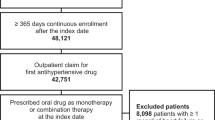

Residents aged at least 65 years old with an estimated life expectancy of at least 3 months (based on clinical judgement) were invited to take part in the study. Of 664 eligible residents, 603 were invited to participate, from which 220 were excluded or did not participate due to declining to participate (n = 106); feeling unwell or being hospitalized (n = 34); unable to obtain consent (n = 54); and other reasons (n = 25). The 383 residents who participated in the study were representative of all residents of the six aged care services in terms of age [mean (standard deviation, SD) 87.5 years (SD 6.2) vs 87.3 years (SD 6.4); P = 0.66], sex (77.5% female vs 78.5% female; P = 0.90), and dementia diagnosis (44.1% vs 46.8%; P = 0.72). Of these 383 residents, those with a current diagnosis of hypertension documented in the medical record and prescribed at least one antihypertensive were included in the present analysis (n = 239). This ensured a specific sample of residents who were being treated with antihypertensives for diagnosed hypertension, allowing us to make comparisons between multiple therapy and monotherapy for this indication.

Data collection

Residents were assessed by study nurses who received training in the administration of the study assessment tools. A full list of the study assessment tools and scales has been reported previously [27]. For assessments requiring the input of a staff member, staff must have known the resident for a minimum of 2 weeks. Demographic, diagnostic and medication data were extracted directly from the resident’s electronic medical record and medication chart. Other clinical data were obtained using a standardized data extraction form.

Medication assessment

All medications prescribed to participating residents were classified according to the anatomical therapeutic chemical (ATC) classification system [28]. Antihypertensive medications were defined as antiadrenergic agents and others (ATC code, C02), diuretics (C03), beta blockers (C07), calcium-channel blockers (C08), angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors (C09A, C09B), and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) (C09C, C09D). Fixed dose combination products were classed as the use of two antihypertensives. Treatment was classified as multiple antihypertensive therapy, if participants used two or more different antihypertensive medications concurrently.

Main outcomes

The primary outcome was all-cause mortality during the 2-year follow-up period. Date of death was extracted from the electronic medical records of the participating aged care services. The secondary outcome was number of cardiovascular-related hospitalizations during the 2-year follow-up period. Data on hospitalizations were extracted from electronic medical records of the aged care provider. Cardiovascular-related hospitalizations were defined as International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM) codes 100-199, and were coded and reviewed independently by two clinical pharmacists.

Covariates

Demographic variables included age and sex. Dementia status was determined according to whether or not a dementia diagnosis of any type was recorded in each resident’s medical record. Dementia severity was assessed in all residents with and without a documented dementia diagnosis using the Dementia Severity Rating Scale (DSRS) [29]. Frailty was assessed using the FRAIL-NH scale [26, 30]. The FRAIL-NH was specifically developed for use in aged care services and included seven items (energy, transferring, mobility, continence, weight loss in the last 3 months, feeding and dressing) and was constructed based on clinical data. Data on clinically relevant cardiovascular and endocrine comorbidities including myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease and diabetes were extracted from each resident’s electronic medical record. Charlson’s comorbidity index score was computed and used as an indicator of comorbidity [31].

Statistical analysis

Inverse probability weighting (IPW) was used to address confounding by observed covariates at baseline. Weights were based on results from a treatment selection model, estimated using logistic regression with use of multiple antihypertensives as the dependent variable and the baseline variables—age, sex, DSRS, FRAIL-NH, Charlson’s comorbidity index, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, cerebrovascular disease, diabetes and dementia—as independent variables. The weights for each resident were calculated as the inverse of the probability of receiving the treatment the resident actually received conditional on observed covariates. After weighting, we assessed the balance of baseline characteristics between treatment groups using standardized mean differences (SMD) with an absolute SMD ≥ 20% or 0.2 defined as a meaningful difference [32]. Kaplan–Meier curves were produced to estimate survival and the log rank test was used to determine statistical significance. Cox proportional hazard models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the association between multiple antihypertensive use and all-cause mortality. Residents that survived beyond the 2-year follow-up period were right-censored at 730 days (2 years). To assess the potential modifying effect of dementia and frailty, further analyses were conducted stratifying by documented dementia diagnosis and FRAIL-NH score (≥ 6 considered most frail). This cut-point of the FRAIL-NH scale to determine which residents were most frail was based on previously published analyses [26]. Multiplicative interaction was assessed by including main effect variables and their product terms in a Cox proportional hazards model. The incidence rate of cardiovascular-related hospitalizations was calculated assuming a Poisson distribution. Multiple imputation with five iterations was used to impute missing data. Sensitivity analyses, repeating the main analyses using multiple imputation, IPW and adjustment, were performed to assess robustness of results. All statistical analyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows v 23.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) and SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

The analyses included 239 residents with a mean age of 88.1 (6.3) years at baseline with the majority being female (79.1%). A total of 70 (29.3%) residents received one antihypertensive and 169 (70.7%) received multiple antihypertensives. The most prevalent antihypertensives were diuretics (144, 60.3%), beta blockers (110, 46.0%), ACE inhibitors (75, 31.4%), ARBs (74, 31.0%) and calcium-channel blockers (70, 29.3%). Baseline characteristics according to antihypertensive use are reported in Table 1.

During the follow-up period (mean 1.58 years), 86 (36.0%) residents died. The crude incidence rates for death were higher in those who used multiple antihypertensives compared with monotherapy (251 [95%CI 194–319]/1000 person-years and 173 [95%CI 111–268]/1000 person-years, respectively). Figures 1 and 2 show the survival curves by antihypertensive use stratified by dementia and frailty status, respectively. Overall, residents who used multiple antihypertensives had a greater risk of all-cause mortality compared with monotherapy (HR 1.40, 95%CI 1.03–1.92) (Table 2). After stratifying by dementia status, the risk remained significant only in those with diagnosed dementia (HR 1.91, 95%CI 1.20–3.04). When considering frailty status, only those who were most frail (FRAIL-NH score ≥ 6) remained at increased risk of mortality (HR 2.52, 95%CI 1.13–5.64). Sensitivity analyses revealed similar findings (online resource 1).

There were no differences in rates of cardiovascular-related hospitalizations between those who used multiple antihypertensives compared to monotherapy (77.9 [95%CI 40.5–149.6]/1000 person-years vs 57.1 [95%CI 34.4–94.7]/1000 person-years, respectively; rate ratio [multiple compared with monotherapy]: 0.73 [95%CI 0.32–1.67]).

Discussion

The main finding was that residents with diagnosed hypertension who used multiple antihypertensives had a 40% increased risk of mortality over a 2-year follow-up compared to residents using monotherapy. After stratification, the increased risk of mortality was only significant among residents with a documented diagnosis of dementia and those who were most frail.

The use of multiple antihypertensive therapy in older people has increased significantly over the last two decades. A study of United Kingdom primary care electronic health records of individuals 80 years and over found that BP treatment intensified between 2001 and 2014 with the proportion of people treated with multiple antihypertensives increasing from approximately one-third to nearly one-half [33]. Conversely, in the United States the prescription of multiple antihypertensives among community-dwelling older adults with dementia remained constant between 2006 and 2012 [34]. Limited studies have investigated the trends in multiple antihypertensive use or the corresponding association with mortality in older adults residing in residential aged care services [23]. The PARTAGE study found a significant interaction between low SBP and treatment with multiple antihypertensives, with an increased risk of mortality (HR 1.78, 95%CI 1.34–2.37) [23]. The PARTAGE study did not present results stratified by dementia or frailty status; however, multiple antihypertensive therapy alone in all residents did not increase risk of mortality.

Few studies have focused on the management of hypertension in individuals with established dementia [35]. Previous research has reported that in adults ≥ 65 years of age with cognitive impairment treated with antihypertensive therapy, low SBP was associated with an increased risk of mortality [36, 37]. In our study, we found that multiple antihypertensive therapy use was significantly associated with mortality in those with diagnosed dementia. Residents with dementia may be frailer and more prone to adverse drug events. Indeed, in separate sub-analyses we found that the risk of mortality associated with multiple antihypertensive use was only significant in those who were most frail. Frailty has been reported to be associated with orthostatic hypotension and fall-related injuries, thus the use of multiple antihypertensives may further exacerbate these adverse outcomes in a population that are physiologically vulnerable and have low resilience to stressors [38].

Our findings further highlight the importance of considering functional and cognitive status when treating hypertension in older adults. The Milan Geriatrics 75 + Cohort study found that the correlations of BP with mortality were U-shaped and that higher SBP was related to lower mortality in people with impaired Mini-Mental State Examination and Activities of Daily Living [16]. Odden et al. found evidence that frailty status measured in terms of walking speed modified the association between blood pressure and mortality [17]. Among faster walkers ≥ 65 years of age, elevated SBP was associated with greater mortality, whereas in frail participants, the association was less clear. However, the modifying effects of frailty on the association between antihypertensive use and mortality risk are less consistent, with some studies showing no significant effect [37,38,39]. The HYVET and SPRINT studies reported no significant interaction between baseline frailty and antihypertensive treatment on risk of death [10, 39]. This finding is likely explained by these studies excluding particularly vulnerable individuals including residents of aged care services, individuals with diagnosed dementia, and those with conditions likely to limit life expectancy to less than 1-3 years, which is in contrast to our study population [39]. The most frail participants in our study may have been considerably frailer than participants deemed frail in the HYVET and SPRINT studies [40]. Disability and frailty are closely linked; frailty may be a cause of disability and frailty and disability may co-occur [41]. In our study, frailty was measured using the FRAIL-NH which captures components of disability, not only frailty. While the FRAIL-NH captures a broader range of items, the extent to which disability, rather than frailty, was assessed should be considered when interpreting our findings. The FRAIL-NH has been previously shown to be comparable to the frailty index for assessing frailty in our study population [26].

Tight BP control (< 140/90 mmHg) is generally not recommended for individuals with advanced dementia or functional limitation due to lack of evidence to suggest that BP goal attainment of 140–159 mmHg improves morbidity or reduces mortality [18]. Nevertheless, there is strong evidence to suggest that treating BP > 160 mmHg in older people is beneficial. Tight BP control of < 140/90 mmHg is also not recommended for those with a life expectancy less than 2 years and the use of multiple antihypertensives should be avoided in order to minimize difficulties with adherence to complex medication regimens [18]. Interestingly, in the PARTAGE study higher BP was not associated with a higher risk of mortality or major cardiovascular events in residents of aged care services [42].

Ravindrarajah et al. report a terminal decline in SBP in the final 2 years of life suggesting that associations of low SBP with higher mortality may be accounted for by reverse causation [43]. While it is not possible to determine whether residents on multiple antihypertensive medications were being treated appropriately in our study, it is possible that the findings indicate a failure to deprescribe as blood pressure levels declined toward the end of life.

This study provides insight into the potential risks associated with intensive BP lowering in residents of aged care services. It is possible that reducing cardiovascular risk may need to be balanced against the risk of adverse drug events. We did not have access to data on cardiovascular-related mortality; however, there was no difference in the rate of cardiovascular-related hospitalizations among residents receiving multiple compared to monotherapy with antihypertensives. Given this vulnerable population is often excluded from clinical trials, and there remains controversy regarding appropriateness of antihypertensive treatment [44]; this highlights the need for guidelines for hypertension management in aged care services, including in residents with dementia and among those who are most frail.

Strengths and limitations

Our study has strengths and limitations. Medication and comorbidity data were collected at baseline only, thus it was not possible to assess possible changes in antihypertensive medications over the follow-up period. Similarly, dementia diagnosis and frailty status were only assessed at baseline. Participants and non-participants in our study were similar in key demographics, suggesting our sample was representative of all residents in the six aged care services from which they were recruited. However, Australian residential aged care services increasingly cater to the frailest subset of older people, and therefore, our findings may not be generalizable to recipients of aged care services in other countries or settings. A limitation is that we did not have data on each resident’s BP. It is possible that residents taking multiple antihypertensives had poorer BP control and cardiovascular health than residents using monotherapy. However, we adjusted our analyses for cardiovascular comorbidities and found no difference in cardiovascular-related hospitalizations in residents using multiple or monotherapy. Interestingly, the average BP measurements of residents using multiple antihypertensives and monotherapy were similar in the PARTAGE study [23]. In addition, we only had information on baseline use of antihypertensives and no information on when medication was initiated. Antihypertensive use, therefore, would have affected BP at baseline which may have been on the causal pathway of antihypertensive use and mortality [45]. We did limit our analyses to residents with diagnosed hypertension and adjusted our analyses for a range of clinically important cardiovascular comorbidities that were likely to be associated with the risk of cardiovascular death. However, in restricting the sample to residents with a current diagnosis of hypertension, we excluded normotensive residents who may have been prescribed antihypertensive medications for other cardiovascular comorbidities. The risk-to-benefit ratio of antihypertensive therapy may have been different in these residents. In addition, we were unable to validate hypertension diagnosis. The 2-year follow-up period is relatively short but consistent with the average length of stay in Australian residential aged care services of 2.9 years [46]. Finally, we were only able to investigate all-cause mortality rather than cause-specific mortality including cardiovascular-specific death. However, we found no differences in the rates of cardiovascular-related hospitalizations, a proxy for major cardiovascular events, between groups.

Conclusions

The use of multiple antihypertensive therapy in older people with hypertension residing in aged care services may be associated with an increased risk of mortality, especially in those with dementia and who are most frail. The risk-versus-benefit of using intense antihypertensive regimens should be carefully assessed in these vulnerable resident groups. Clinicians may need to balance the benefits of BP lowering with the potential risk of adverse drug events.

References

Weiss J, Freeman M, Low A et al (2017) Benefits and harms of intensive blood pressure treatment in adults aged 60 years or older: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 166:419–429. https://doi.org/10.7326/m16-1754

Lim KK, Sivasampu S, Khoo EM (2015) Antihypertensive drugs for elderly patients: a cross-sectional study. Singapore Med J 56:291–297. https://doi.org/10.11622/smedj.2015019

Zeglin Magdalena A, Pacos Jason, Bisognano JD (2009) Hypertension in the very elderly: brief review of management. Cardiol J 16:379–385

Aronow WS, Fleg JL, Pepine CJ et al (2011) ACCF/AHA 2011 expert consensus document on hypertension in the elderly: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Task Force on Clinical Expert Consensus Documents developed in collaboration with the American Academy of Neurology, American Geriatrics Society, American Society for Preventive Cardiology, American Society of Hypertension, American Society of Nephrology, Association of Black Cardiologists, and European Society of Hypertension. J Am Soc Hypertens 5:259–352. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jash.2011.06.001

Hakala SM, Tilvis RS, Strandberg TE (1997) Blood pressure and mortality in an older population: a 5-year follow-up of the Helsinki Ageing Study. Eur Heart J 18:1019–1023

Briasoulis A, Agarwal V, Tousoulis D et al (2014) Effects of antihypertensive treatment in patients over 65 years of age: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled studies. Heart 100:317–323

Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N et al (2002) Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 360:1903–1913

Lernfelt B, Svanborg A (2002) Change in blood pressure in the age interval 70–90. Late blood pressure peak related to longer survival. Blood Press 11:206–212

Delgado J, Masoli JAH, Bowman K et al (2017) Outcomes of treated hypertension at age 80 and older: cohort analysis of 79,376 individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc 65:995–1003. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14712

Williamson JD, Supiano MA, Applegate WB et al (2016) Intensive vs Standard blood pressure control and cardiovascular disease outcomes in adults aged ≥ 75 years: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA 315:2673–2682. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.7050

Beckett NS, Peters R, Fletcher AE et al (2008) Treatment of hypertension in patients 80 years of age or older. N Engl J Med 358:1887–1898

National Heart Foundation of Australia (2016) Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in adults—2016. National Heart Foundation of Australia, Melbourne

Tu K, Anderson LN, Butt DA et al (2014) Antihypertensive drug prescribing and persistence among new elderly users: implications for persistence improvement interventions. Can J Cardiol 30:647–652. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cjca.2014.03.017

Mosnaim AD, Abiola R, Wolf ME et al (2010) Etiology and risk factors for developing orthostatic hypotension. Am J Ther 17:86–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3181a2b1bb

Sun BC, Emond JA, Camargo CA Jr (2004) Characteristics and admission patterns of patients presenting with syncope to US emergency departments, 1992–2000. Acad Emerg Med 11:1029–1034

Ogliari G, Westendorp RG, Muller M et al (2015) Blood pressure and 10-year mortality risk in the Milan Geriatrics 75 + Cohort Study: role of functional and cognitive status. Age Ageing 44:932–937. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv141

Odden MC, Peralta CA, Haan MN et al (2012) Rethinking the association of high blood pressure with mortality in elderly adults: the impact of frailty. Arch Intern Med 172:1162–1168. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.2555

Onder G, Landi F, Fusco D et al (2014) Recommendations to prescribe in complex older adults: results of the CRIteria to assess appropriate Medication use among Elderly complex patients (CRIME) project. Drugs Aging 31:33–45

Onder G, Vetrano DL, Marengoni A et al (2018) Accounting for frailty when treating chronic diseases. Eur J Intern Med 56:49–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2018.02.021

Vetrano DL, Palmer KM, Galluzzo L et al (2018) Hypertension and frailty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 8:e024406. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024406

Welsh TJ, Gladman JR, Gordon AL (2014) The treatment of hypertension in people with dementia: a systematic review of observational studies. BMC geriatrics 14:19. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-14-19

Palmer K, Villani ER, Vetrano DL et al (2019) Association of polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy with frailty states: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Geriatr Med 10:9–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41999-018-0124-5

Benetos A, Labat C, Rossignol P et al (2015) Treatment with multiple blood pressure medications, achieved blood pressure, and mortality in older nursing home residents: the PARTAGE Study. JAMA Intern Med 175:989–995

Sluggett JK, Ilomaki J, Seaman KL et al (2017) Medication management policy, practice and research in Australian residential aged care: current and future directions. Pharmacol Res 116:20–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.phrs.2016.12.011

The National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling NATSEM (2017) Economic cost of dementia in Australia 2016–2056. Alzheimer’s Australia, Canberra

Theou O, Tan EC, Bell JS et al (2016) Frailty levels in residential aged care facilities measured using the frailty index and FRAIL-NH scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 64:e207–e212. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14490

Tan ECK, Visvanathan R, Hilmer SN et al (2014) Analgesic use, pain and daytime sedation in people with and without dementia in aged care facilities: a cross-sectional, multisite, epidemiological study protocol. BMJ Open 4:e005757

WHO Collaborating Centre for Drug Statistics Methodology (2019) ATC classification index with DDDs, Oslo, Norway

Clark CM, Ewbank DC (1996) Performance of the dementia severity rating scale: a caregiver questionnaire for rating severity in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 10:31–39

Kaehr E, Visvanathan R, Malmstrom TK et al (2015) Frailty in nursing homes: the FRAIL-NH scale. J Am Med Dir Assoc 16:87–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.12.002

Buntinx F, Niclaes L, Suetens C et al (2002) Evaluation of Charlson’s comorbidity index in elderly living in nursing homes. J Clin Epidemiol 55:1144–1147

Yang D, Dalton JE (2012) A unified approach to measuring the effect size between two groups using SAS. SAS Global Forum

Ravindrarajah R, Dregan A, Hazra NC et al (2017) Declining blood pressure and intensification of blood pressure management among people over 80 years: cohort study using electronic health records. J Hypertens 35:1276–1282. https://doi.org/10.1097/hjh.0000000000001291

Tan EC, Bell JS, Lu CY et al (2016) National trends in outpatient antihypertensive prescribing in people with dementia in the United States. J Alzheimers Dis 54:1425–1435. https://doi.org/10.3233/jad-160470

van der Wardt V, Logan P, Conroy S et al (2014) Antihypertensive treatment in people with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc 15:620–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2014.03.005

Mossello E, Pieraccioli M, Nesti N et al (2015) Effects of low blood pressure in cognitively impaired elderly patients treated with antihypertensive drugs. JAMA Intern Med 175:578–585. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.8164

Streit S, Poortvliet RKE, Gussekloo J (2018) Lower blood pressure during antihypertensive treatment is associated with higher all-cause mortality and accelerated cognitive decline in the oldest-old-data from the Leiden 85-plus study. Age Ageing. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afy072

Odden MC, Beilby PR, Peralta CA (2015) Blood pressure in older adults: the importance of frailty. Curr Hypertens Rep 17:55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-015-0564-y

Warwick J, Falaschetti E, Rockwood K et al (2015) No evidence that frailty modifies the positive impact of antihypertensive treatment in very elderly people: an investigation of the impact of frailty upon treatment effect in the hypertension in the very elderly trial (HYVET) study, a double-blind, placebo-controlled study of antihypertensives in people with hypertension aged 80 and over. BMC Med 13:78. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-015-0328-1

Russo G, Liguori I, Aran L et al (2018) Impact of SPRINT results on hypertension guidelines: implications for “frail” elderly patients. J Hum Hypertens 32:633–638. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41371-018-0086-6

Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J et al (2004) Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol Ser A 59:M255–M263. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/59.3.M255

Benetos A, Gautier S, Labat C et al (2012) Mortality and cardiovascular events are best predicted by low central/peripheral pulse pressure amplification but not by high blood pressure levels in elderly nursing home subjects: the PARTAGE (predictive values of blood pressure and arterial stiffness in institutionalized very aged population) study. J Am Coll Cardiol 60:1503–1511. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2012.04.055

Ravindrarajah R, Hazra NC, Hamada S et al (2017) Systolic blood pressure trajectory, frailty, and all-cause mortality > 80 years of age: cohort study using electronic health records. Circulation 135:2357–2368. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.116.026687

Kantoch A, Gryglewska B, Wojkowska-Mach J et al (2018) Treatment of cardiovascular diseases among elderly residents of long-term care facilities. J Am Med Dir Assoc 19:428–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2017.12.102

Schisterman EF, Cole SR, Platt RW (2009) Overadjustment bias and unnecessary adjustment in epidemiologic studies. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 20:488–495. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181a819a1

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (2017) GEN fact sheet 2015–16: people leaving aged care. AIHW, Canberra

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Resthaven staff and residents for their participation in this study.

Funding

The data used for this study were collected with support from the Alzheimer Australia Dementia Research Foundation via the Resthaven Incorporated Dementia Research Award. ECKT was supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council-Australian Research Council (NHMRC-ARC) Dementia Research Development Fellowship (APP1107381). JSB was supported by an NHMRC Dementia Leadership Fellowship. JI was supported by an NHMRC Early Career Fellowship. NJ was supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Statement of human and animal rights

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Royal Australian College of General Practitioners National Research and Evaluation Ethics Committee and the Monash University Health Research Ethics Committee, and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study. Where residents were unable to provide informed consent, consent was obtained from a guardian, next of kin, or significant other.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kerry, M., Bell, J.S., Keen, C. et al. Multiple antihypertensive use and risk of mortality in residents of aged care services: a prospective cohort study. Aging Clin Exp Res 32, 1541–1549 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-019-01336-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40520-019-01336-x