Abstract

The occurrence of several geriatric conditions may influence the efficacy and limit the use of drugs prescribed to treat chronic conditions. Functional and cognitive impairment, geriatric syndromes (i.e. falls or malnutrition) and limited life expectancy are common features of old age, which may limit the efficacy of pharmacological treatments and question the appropriateness of treatment. However, the assessment of these geriatric conditions is rarely incorporated into clinical trials and treatment guidelines. The CRIME (CRIteria to assess appropriate Medication use among Elderly complex patients) project is aimed at producing recommendations to guide pharmacologic prescription in older complex patients with a limited life expectancy, functional and cognitive impairment, and geriatric syndromes, and providing physicians with a tool to improve the quality of prescribing, independent of setting and nationality. To achieve these aims, we performed the following: (i) Existing disease-specific guidelines on pharmacological prescription for the treatment of diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation and coronary heart disease were reviewed to assess whether they include specific indications for complex patients; (ii) a literature search was performed to identify relevant articles assessing the pharmacological treatment of complex patients; (iii) A total of 19 new recommendations were developed based on the results of the literature search and expert consensus. In conclusion, the new recommendations evaluate the appropriateness of pharmacological prescription in older complex patients, translating the recommendations of clinical guidelines to patients with a limited life expectancy, functional and cognitive impairment, and geriatric syndromes. These recommendations cannot represent substitutes for careful clinical consideration and deliberation by physicians; the recommendations are not meant to replace existing clinical guidelines, but they may be used to help physicians in the prescribing process.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The aging process is characterized by a high level of complexity, which makes the care of older adults particularly challenging. Typically, older adults exhibit the co-occurrence of multiple chronic diseases (comorbidity) and conditions—such as urinary incontinence, delirium, or falls—that cannot be ascribed to a specific organ system pathology and that have multiple causes (the so-called geriatric syndromes) [1]. Both comorbidity and geriatric syndromes contribute to increase the rate of disability, mortality and poor outcomes seen in older patients (for example, institutionalization and death) [2]. This high degree of complexity is complicated by the presence of cognitive impairment, which is common in this population. Social problems, such as lack of informal support or poor income, are also widely represented in this age group.

Consequently, physicians are facing challenging patients who present with an array of concomitant clinical conditions, whose integration and cumulative effects result in different degrees of functional deficits, cognitive deterioration, nutritional problems, and geriatric syndromes (delirium, falls, incontinence), in addition to a lack of social support and financial resources. As such, this ‘modern’ patient presents a degree of complexity never before considered by traditional medicine.

In particular, pharmacological treatment of this complex patient represents a challenge for the prescribing physician [3, 4]. This challenge is confirmed by the high rate of adverse drug reactions observed in this older population. In Western countries, drug-related illnesses cause 3–5 % of all hospital admissions, account for 5–10 % of in-hospital costs and are associated with a substantial increase in morbidity and mortality. The rate and severity of adverse drug reactions seem to be higher in clinically complex patients [5–8].

The occurrence of several geriatric conditions may influence the efficacy and limit the use of medications prescribed to treat chronic conditions. Functional and cognitive impairment, geriatric syndromes (i.e. falls or malnutrition) and limited life expectancy are common features of old age, which may limit the efficacy of pharmacological treatments indicated by guidelines, and raise questions about the appropriateness of treatment. Multiple underlying factors, involving chronic and acute diseases, tend to contribute to the development of these geriatric conditions. In some cases, overlap of multiple diseases, involving different organs, may result in the onset of a geriatric condition. The fact that these conditions cross organ systems and discipline-based boundaries, along with their multifactorial nature, challenges traditional ways of viewing clinical care and research. Indeed, applying the recommendation of clinical guidelines to complex elderly individuals is not straightforward since the level of evidence on which they are based (and therefore the strength) relies on randomized clinical trials (RCTs) or meta-analyses which are usually conducted on young and adult subjects, with only one disease and limited (if any) comorbidities, usually strictly related to the target disease. Patients recruited in trials take a limited number of drugs, almost all for conditions related to the specific disease studied, and for a short period of time (months or, at most, a few years). Therefore, it may be difficult to extrapolate their results to older complex people, with many comorbid conditions, who use many different drugs, are cognitively impaired and are disabled. This concept emphasizes the need for an interaction of pharmacological treatment with these geriatric conditions, which are rarely incorporated in clinical trials and treatment guidelines.

The presence of functional deficits and disability may limit the ability of patients to take medicines accurately. Functional deficits are related to a reduced ability to manage pill containers and, therefore, to the patient’s reduced compliance with medication [9]. Cognitive impairment and dementia are associated with memory loss, decline in intellectual function, and impaired judgment and language, which may have obvious effects on the patient’s decision-making capability. Cognitive impairment and dementia can alter the benefits and burdens, impact treatment adherence, and cause communication difficulties, including a decreased ability to report adverse effects [10, 11], Additionally, the presence of geriatric syndromes may influence the effect of pharmacological treatment. The term ‘geriatric syndromes’ refers to one symptom or a complex of symptoms, resulting from multiple diseases and multiple risk factors [1]. Geriatric syndromes can have a devastating effect on the quality of life of elderly patients. Specific syndromes such as falls or malnutrition have some direct implications for how intensely providers may actually manage chronic diseases. Other geriatric syndromes, such as depression, orthostatic hypotension, urinary incontinence and chronic pain are more common among elderly patients with chronic diseases and may be of great importance to the patient. The presence of these syndromes may influence the potential benefits of pharmacological treatments [3, 4]. Research studies have clearly demonstrated that drugs are frequently implicated in their pathogenesis. Finally, the estimation of life expectancy is important to understand whether a patient can benefit from a certain treatment [12].

Despite their relevance, these above-mentioned factors are rarely considered by clinical guidelines that aim to provide patients with the best quality of care. Although the clinical guidelines propose appropriate prescription for standardizing management and treating medical conditions, they seldom address the common problems encountered in geriatric care. With a few notable exceptions [13], they do not provide indications for the treatment of subjects with limited life expectancy; they tend to focus on reducing mortality rather than quality-of-life issues. Cognitive impairment is rarely discussed as a possible modifier of the treatment plan, although one in five of those patients over 80 years of age will develop a clinically detectable form of dementia. Geriatric syndromes and disability generally receive little attention, notwithstanding the fact that physicians of any specialty will see every day patients who suffer from these debilitating conditions.

2 Purpose and Methodology

Given this background, the purpose of the CRIteria to assess appropriate Medication use among Elderly complex patients (CRIME) project is to issue recommendations to assess appropriateness of pharmacological treatments indicated by clinical guidelines in older complex patients, with limited life expectancy, functional and cognitive impairment, and geriatric syndromes, giving physicians a tool to guide drug use prescribing independent of setting and nationality.

To achieve these aims, we performed the following:

-

1.

Existing disease-specific guidelines on pharmacological prescription for the treatment of the diseases more commonly observed in the elderly were analyzed to determine if they include specific indications for complex patients with limited life expectancy, functional and cognitive impairment, and geriatric syndromes.

-

2.

A literature search was performed to identify relevant articles that assess pharmacological treatment of five common chronic conditions (diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and coronary heart disease) in complex patients with limited life expectancy, functional and cognitive impairment, and geriatric syndromes to integrate recommendations of disease-specific guidelines.

-

3.

New recommendations were developed based on the data derived from the literature search and consensus.

2.1 Review of Disease-Specific Guidelines

Guidelines on the treatment of the following diseases were analyzed: diabetes, hypertension, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and coronary heart disease. These diseases were chosen because they were associated with the highest pharmacological burden and because the drugs used in their treatment most frequently cause adverse drug reactions [5–7]. Two sets of guidelines for each disease were chosen based on consensus within the CRIME research group. For each of the examined diseases, two sets of guidelines were selected based on the consensus among CRIME researchers (see Appendix 1 for a list of guidelines examined). The majority of the updated guidelines were reviewed by two independent researchers (GO and MB), who addressed the following issues: (i) Do the guidelines address treatment for older adults? (ii) Is there a discussion regarding the time required for patients to benefit from treatment in the context of life expectancy? (iii) Are specific recommendations for patients with cognitive impairment included in the guidelines? (iv) Are specific recommendations for patients with disability and functional impairment included in the guidelines? (v) Are specific recommendations for patients with geriatric syndromes included in the guidelines?

2.2 Literature Search

A literature search was performed by two independent assessors (GO and DF). For each specific disease examined, relevant studies were identified through PubMed searches of the MEDLINE database using a term to identify the disease of interest (i.e. ‘diabetes’) and ‘treatment’ and ‘older adults’ and each of the following terms: ‘life expectancy’, ‘end of life’, ‘functional impairment’, ‘disability’, ‘cognitive impairment’, ‘dementia’, ‘geriatric syndromes’, ‘falls’, ‘incontinence’, ‘malnutrition’. Bibliographies of the retrieved articles were searched to identify other eligible studies. Non-English articles were not included in the search. Additional searches will be performed using the National Library of Medicine clinical trials database and the Cochrane Collaboration Library database. The search was extended through June 2012. Data from both randomized, controlled trials and observational studies were assessed to fulfill our aims. This expansion of the literature search was necessary because of the limited availability of data on complex older patients from RCTs. Articles were screened to evaluate if they were assessing the efficacy of pharmacological treatments recommended by guidelines in a sample of older adults with limited life expectancy, functional impairment or cognitive impairment, or geriatric syndromes.

2.3 New Recommendations

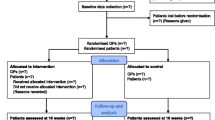

Based on results of the literature search, disease-specific recommendations were agreed on a consensus basis within the CRIME research group. For each recommendation, a brief description of its ‘rationale’ was produced. Each of these recommendations was subsequently examined by seven experts from leading Italian and international geriatric research centers, who rated, through a web-based questionnaire, the recommendations on a scale of 0–10. Experts were identified as having a predominant research focus on aging or pharmacoepidemiology (see Appendix 2 for a list of experts). Only those recommendations that received a mean score of ≥8 were selected. Figure 1 summarizes the literature search and new recommendation production process for each of the diseases of interest.

3 Results and Recommendations

The results of the review of disease-specific guidelines are presented in Table 1. All ten of the guidelines examined addressed the issue of pharmacological treatment in older adults. However, the common conditions that are associated with advanced aging, including limited life expectancy, functional and cognitive impairment, and geriatric syndromes, were rarely addressed.

Based on the articles identified by the literature search, a set of 23 new recommendations were produced. Overall, 19 recommendations received a mean rating of ≥8 and were selected.

3.1 Diabetes

Recommendation 1: In patients with limited life expectancy (<5 years) or functional limitation, intensive glycemic control (HbA1c <7 %) is not recommended.

Rationale: A glycemic goal set by current guidelines is HbA1c <7.0 %. However, many studies suggest the need for individual target, considering age and life expectancy, duration of diabetes, comorbid conditions, advanced diabetes complications, and risk of hypoglycemia unawareness [14–17].

Limited life expectancy is an important determinant of the magnitude of the expected benefit of intensive glucose control compared with moderate glucose control. It was suggested that 5 years of life expectancy is an acceptable threshold for identifying older patients who are unlikely to benefit from intensive control [18]. Finally, the presence of functional impairments and poor physical performance was shown to be an important predictor for reduced benefits from intensive glucose control [19].

Recommendation 2: In patients with a history of falls or cognitive impairment or dementia, intensive glycemic control (HbA1c of <7 %) or use of insulin is not recommended.

Rationale: In studies of diabetic patients, the risk of falls is higher in patients with diabetic complications (renal insufficiency, peripheral neuropathy, retinopathy) and in those using insulin with low HbA1c [20]. This could contribute to the high risk of fractures documented in diabetic patients who are treated with insulin [21]. Other studies have shown that the risk of fall is higher in diabetic women who use insulin [22, 23] and that tight glycemic control is associated with an increased risk of falling in frail older adults [24].

The presence of cognitive impairment or dementia was shown to be an important risk factor for hypoglycemia due to disorders related to eating habits or poor treatment management [25, 26]. Additionally, tight glycemic control was associated with increased risks of developing dementia in frail, diabetic, elderly patients with hypoglycemic episodes [27, 28].

Patients with cognitive impairment or dementia may have difficulties naming their medications and describing their indications; they more frequently hold health beliefs that interfere with adherence to their medical regimen, and they are more likely to have a poor understanding of their condition and its management. In addition, in patients with diabetes, presence of dementia or cognitive impairment may alter the ability of patients to fully participate in their self-care and adhere to complex treatments without special assistance [29, 30]. In particular, the use of insulin is common among individuals with cognitive impairment; these patients are significantly more likely not to know what to do in the event of hypoglycemia, and they tend to give more incorrect responses when asked about diabetes mellitus management than do those who are cognitively intact [31].

Recommendation 3: In patients with a recent fall or high risk of falls or orthostatic hypotension, intensive blood pressure lowering (<130/80 mmHg) is not recommended.

Rationale: Blood pressure goals for diabetic patients are <130/80 mmHg, so that intervention is suggested for persons in the ‘pre-hypertension’ group. Available antihypertensive drugs are usually safe and can be used in combination to attain the suggested therapeutic goals. However, an obvious concern in elderly diabetic patients is the possibility of autonomic dysregulation and orthostatic hypotension, which is very common in this population [32]. Orthostatic hypotension has been related to poor cardiovascular prognosis and is a common cause of falls [33]. The number of medications in use is associated with postural blood pressure changes, and some classes of drugs used to treat multiple chronic conditions (antihypertensives in particular, but also nitrates, drugs for Parkinson’s disease, antipsychotics and tricyclic antidepressants) can have a causative role [34]. When patients start antihypertensive therapy, the patients’ orthostatic hypotension should be routinely checked and reassessed regularly. Therefore, in patients with known autonomic dysregulation, a history of falls, or a high risk for falls, the blood pressure goals should be less stringent. This advice seems prudent, particularly if stricter control must be attained with complex drug schedules.

Recommendation 4: Use of statins in older adults with limited life expectancy (<2 years) or advanced dementia is not recommended.

Rationale: There is ample evidence of the usefulness of statins in secondary prevention. Withholding statins in older diabetic patients after acute coronary syndromes or with known cardiovascular disease (CVD) should not be considered good medical practice. The benefit of statin therapy has been demonstrated in primary prevention in a high-risk population without overt CVD (although significant differences exist among the studies), as outlined by recent reviews [35, 36].

However, the benefits of statin use decrease with increasing age [37]. The results of a meta-analysis [38] in patients with diabetes indicated that the benefits of statin therapy are evident and substantial after at least 2 years of therapy. Therefore, the use of statins may not lead to any beneficial effect in patients with limited life expectancy, including those with advanced dementia. A consensus statement of geriatricians indicated that the use of statins is never appropriate in patients with advanced dementia [39].

Recommendation 5: Metformin should be avoided in malnourished (body mass index <18.5 kg/m 2) older adults.

Rationale: In overweight individuals, metformin has been associated with reductions in all-cause mortality and stroke compared with insulin or sulfonylureas [40]. These benefits seem related to the fact that metformin may cause anorexia and weight loss, and this effect is particularly relevant in older adults [41, 42]. For this reason, older patients who are frail, anorexic, or underweight may not be appropriate candidates for metformin therapy [42, 43].

3.2 Hypertension

Recommendation 1: In patients with dementia or cognitive impairment or functional limitation, a tight blood pressure control (<140/90 mmHg) is not recommended.

Rationale: To date, no evidence is available to demonstrate that treating older persons with blood pressure from 140 to 159 mmHg would improve morbidity or mortality. No trial in which a benefit was shown exhibited a systolic blood pressure average <140 mmHg. Although the data are strong and supportive of aggressive blood pressure reduction in older persons with a blood pressure of >160 mmHg, the probable increased risk of adverse effects and perceived lower benefits in the elderly may deter clinicians from aggressively treating hypertension in the elderly [44]. The reality of applying a tight blood pressure control to complex patients may be problematic because of limited compliance and potential medication errors, particularly in patients who have problems managing therapy (due to cognitive impairment, dementia or functional limitations) [45]. Additionally, several publications have suggested that low blood pressure levels are associated with a more rapid cognitive decline in patients with dementia [46–48].

Recommendation 2: In patients with dementia or cognitive impairment or functional limitation, use of more than three antihypertensive drugs should be avoided.

Rationale: Evidence from clinical trials is mostly derived from studies enrolling middle age patients with limited comorbidities and testing the efficacy of one to three antihypertensive agents. Scant data exist about the benefits of additional drugs [49]. Patients with dementia, cognitive impairment, or functional limitation may have difficulties in managing complex drug regimens and their adherence to treatment may be impaired [49, 50]. In particular, several studies have shown that mental health status, patient knowledge, skills in managing the illness, and participation in care affect adherence to the recommended treatments [51].

Recommendation 3: In patients with limited life expectancy (<2 years), a tight blood pressure control (<140/90 mmHg) is not recommended.

Rationale: Patients with terminal illness or end-stage non-CVD should be exempt from the use of complex drug regimens and strict blood pressure control because of different treatment priorities and goals of care, the need to prioritize a clinically dominant illness, and the expectation that the patients may not live long enough to receive the benefits of hypertension treatment [52]. Several studies have indicated that the gain in life expectancy and an event-free life expectancy related to the treatment of hypertension depend on the duration of treatment and, therefore, should be reduced in patients with a short life expectancy [53, 54].

Recommendation 4: In case of falls associated with orthostatic hypotension (or symptomatic orthostatic hypotension), the number of antihypertensive drugs should be reduced and concomitant use of multiple antihypertensive agents should be avoided.

Rationale: The use of antihypertensive medications is associated with an increased risk of falls [55]. This effect seems mediated by orthostatic hypotension. The concomitant use of three or more antihypertensive drugs is associated with an increased risk of orthostatic hypotension [56]. Multifactorial intervention strategies that have proven to prevent falls include a reduction in the number of hypotensive drugs in the presence of orthostatic hypotension [57]. Finally, a recent observational study showed that in hypertensive, community-dwelling, elderly patients, initiating an antihypertensive drug was associated with an immediate increased risk for hip fracture [58].

3.3 Congestive Heart Failure

Recommendation 1: In the presence of orthostatic hypotension or falls, increasing the dosage of antihypertensive drugs is not recommended; the reduction of drug dosages should be considered.

Rationale: Hypotension may be worsened by heart failure treatments, many of which (ACE inhibitors, β-blockers, nitrates, hydralazine) have been associated with decreased blood pressure [59, 60]. This risk for hypotension might also be increased by balance and proprioception decline, as well as the resulting bradyarrhythmias, which may be enhanced by the effects of drugs with negative chronotropic properties (β-blockers) [61]. In addition, patients with geriatric conditions, including falls, are usually excluded from clinical studies assessing the efficacy of drug treatments [62]. The dosage of these drugs should not be increased and the reduction of drug dosages might be considered to allow the continuation of treatment.

Recommendation 2: The chronic use of diuretics in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic older adults with a history of falls and increased fracture risk is not recommended.

Rationale: Non-potassium-sparing diuretics (primarily loop diuretics) remain the cornerstone of therapy for fluid management in patients with heart failure, despite the lack of large randomized trials evaluating their safety and optimal dosing regimens in acute and chronic settings. Chronic use of diuretics in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic heart failure patients, in the absence of signs of fluid retention, is potentially dangerous because of higher risks for hypotension, electrolyte disturbances and worsening renal function [63, 64]. Increased morbidity and mortality have been related to chronic diuretic use in heart-failure patients [65–67]. Increased risks for falls and fracture (both vertebral and hip) have been reported for patients who receive loop diuretics [68]. Diuretics increase the risk of postural and postprandial hypotension. Exposure to high doses of furosemide is associated with worsened outcomes and is broadly predictive of death and morbidity [65–67].

Recommendation 3: Pursuit of low blood pressure targets (systolic blood pressure <130 mmHg) in older adults with dementia or cognitive impairment is not recommended.

Rationale: There is ample evidence that low blood pressure values are associated with poor outcomes (increased mortality, higher hospitalization rate) in patients with heart failure, in the acute, post-acute, and chronic settings [69–74]. In particular, heart failure is a risk factor for cognitive decline and dementia; this association is stronger in the subgroup of patients with lower blood pressure values (systolic blood pressure <130 mmHg; diastolic blood pressure <70 mmHg) [75, 76].

3.4 Atrial Fibrillation

Recommendation 1: In patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and limited life expectancy (<6 months), the use of oral anticoagulants should be avoided.

Rationale: In the management of patients with limited life expectancy, it is important to realize that this type of patient was either excluded or underrepresented in all of the pivotal trials [77]. Expert consensus suggests to withdraw oral anticoagulants in patients with limited life expectancy [78].

Recommendation 2: In non-valvular atrial fibrillation, the use of warfarin in the presence of malnutrition or irregular food intake is not recommended.

Rationale: Nutritional status is a relevant issue in patients who receive warfarin. A stable anticoagulant effect of warfarin is dependent on consistent stores and intake of vitamin K. Impaired nutrition or irregular food intake are common issues in patients with limited life expectancy, and individuals with these conditions who receive warfarin are at risk for overanticoagulation [79, 80]. Additionally, warfarin pharmacokinetics are highly affected by dietary supplements, which are commonly used by malnourished patients [81].

Recommendation 3: In non-valvular atrial fibrillation, the use of anticoagulants is not recommended in elderly patients with dementia if any of the following characteristics are present: unable to manage medications and living alone or high risk for falls.

Rationale: There is consistent evidence that supports an association between atrial fibrillation and increased incidence of dementia, at least in patients with stroke [82]. However, dementia is clearly associated with inadequate international normalized ratio (INR) control, due to poor compliance with warfarin therapy [83–85]. The inability to manage medications, the high risk for falls, and irregular food intake are common conditions in dementia, which are associated with inadequate INR control. A consensus statement of geriatricians indicated that the use of warfarin is rarely appropriate in patients with advanced dementia [39].

Recommendation 4: In patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation and high risk for falls or poor physical performance, the use of anticoagulants is not recommended if the risk for stroke is low.

Rationale: Patients at high risk for falls with atrial fibrillation are at risk for intracranial hemorrhage, especially traumatic intracranial hemorrhage [86]. Several risk scores for bleeding incorporate high risk for falls [87]. However, because of their high stroke rate, atrial fibrillation patients at risk for falls appear to benefit from anticoagulant therapy if they have multiple stroke risk factors [86, 88]. A very low risk for intracranial hemorrhage has been reported by several authors [88]. For patients at risk for falls, indication to anticoagulant therapy should be based on relative risk for stroke/transient ischemic attack (TIA), so that it is no more justified if the risk is low (i.e. CHADS2 score <2 or CHA2DS2-VASc <2) [89]. Poor physical performance is associated with an increased risk for bleeding and falls; individuals with this condition are excluded systematically from trials that assess the efficacy of warfarin in secondary prevention [90–92]. Only 8 % of the 17,046 patients screened were enrolled into the Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Study [91]. Patients with repeated falls or unstable gait were excluded. In the European Atrial Fibrillation Trial of secondary prevention after TIA or minor stroke, 35 % of the patients were ineligible for anticoagulant therapy, with the exclusion of those with moderate-to-severe disability [92]. For this reason, in individuals with low risk for stroke and poor physical performance, use of anticoagulants should be avoided.

Recommendation 5: In patients with known difficulties in managing therapy (i.e. cognitive impairment) and lack of assistance (i.e. caregiver), the use of drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, including digoxin and warfarin, is not recommended.

Rationale: Patients with impaired cognition and low health literacy do not only have limitations in reading, but they may also have difficulties processing oral communication and conceptualizing risk [84, 93]. These patients have greater difficulties naming their medications and describing their indications; they more frequently hold health beliefs that interfere with adherence, and they are more likely to have a poor understanding of their condition and its management. Dementia and cognitive impairment alter the ability of patients to fully participate in their self-care and adhere to complex treatments (including the use of drugs with a narrow therapeutic index, such as digoxin or warfarin) without special assistance [29, 94].

3.5 Coronary Artery Disease

Recommendation 1: The use of statins for secondary prevention in older adults with limited life expectancy (<2 years) or advanced dementia is not recommended.

Rationale: There is evidence of the usefulness of statins in secondary prevention. However, existing data show a reduction in the rate of major cardiovascular events after 2 years of treatment [95]. These data, together with the evidence that the benefits of statin use decrease with increasing age [37], suggest that the use of statins may not lead to any beneficial effect in patients with limited life expectancy (<2 years), including those with advanced dementia. In this context, a consensus statement of geriatricians indicated that the use of statins is never appropriate in patients with advanced dementia [39].

Recommendation 2: In case of orthostatic hypotension, the dosage of antihypertensive drugs should be reduced and the concomitant use of multiple antihypertensive agents should be avoided.

Rationale: Use of antihypertensive medications is associated with an increased risk for falls [55]. This effect seems mediated by orthostatic hypotension. The concomitant use of three or more antihypertensive drugs is associated with an increased risk for orthostatic hypotension [56]. Orthostatic hypotension increases the risk for ischemic heart disease and all-cause mortality in elderly people [96, 97]. Additionally, the early administration of antihypertensive drugs had a potential pro-ischemic effect in hypotension-prone patients after a myocardial infarction [98, 99]. Multifactorial intervention strategies that have proven to prevent falls include the reduction in the dosage of hypotensive drugs in the presence of orthostatic hypotension [57].

4 Conclusions

Prescribing in complex older adults represents a challenging task, and guidelines do not always properly address the appropriateness of medication use in complex older adults. The strength of the CRIME recommendations relates to the fact that they are aimed to evaluate the appropriateness of pharmacological prescription in older complex patients, translating the recommendations of clinical guidelines to patients with limited life expectancy, functional and cognitive impairment, and geriatric syndromes. However, a relevant limitation of these recommendations is due to the fact that they addressed appropriateness of treatment of five chronic diseases and other common conditions (i.e. chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, infective diseases) were not examined. Indeed, the five selected diseases were chosen because they were associated with the highest pharmacological burden and because the drugs used in their treatment most frequently cause adverse drug reactions [5–7]. In addition, level of evidence for the proposed recommendations was not provided because most of the recommendations derived from observational studies, since clinical trials were not performed in patients with the geriatric conditions examined.

In conclusion, these recommendations could represent a tool to improve the quality of prescribing in older adults independent of setting and nationality, but the recommendations are not meant to replace existing clinical guidelines. Clinical studies are needed to test if implementation of these recommendations may result in improving quality of prescribing and reducing the risk of negative outcomes in complex older adults.

References

Lee PG, Cigolle C, Blaum C. The co-occurrence of chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes: the health and retirement study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:511–6.

Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti M, Kuchel GA. Geriatric syndromes: clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780–91.

Onder G, Lattanzio F, Battaglia M, Cerullo F, Sportiello R, Bernabei R, Landi F. The risk of adverse drug reactions in older patients: beyond drug metabolism. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:647–51.

Fusco D, Lattanzio F, Tosato M, Corsonello A, Cherubini A, Volpato S, Maraldi C, Ruggiero C, Onder G. Development of CRIteria to assess appropriate Medication use among Elderly complex patients (CRIME) project: rationale and methodology. Drugs Aging. 2009;26(Suppl 1):3–13.

Budnitz DS, Lovegrove MC, Shehab N, Richards CL. Emergency hospitalizations for adverse drug events in older Americans. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2002–12.

Onder G, Petrovic M, Tangiisuran B, Meinardi MC, Markito-Notenboom WP, Somers A, Rajkumar C, Bernabei R, van der Cammen TJ. Development and validation of a score to assess risk of adverse drug reactions among in-hospital patients 65 years or older: the GerontoNet ADR risk score. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1142–8.

Tangiisuran B, Davies JG, Wright JE, Rajkumar C. Adverse drug reactions in a population of hospitalized very elderly patients. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:669–79.

Zhang M, Holman CD, Price SD, Sanfilippo FM, Preen DB, Bulsara MK. Comorbidity and repeat admission to hospital for adverse drug reactions in older adults: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2009;338:a2752.

Beckman AG, Parker MG, Thorslund M. Can elderly people take their medicine? Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59:186–91.

Vetrano DL, Tosato M, Colloca G, Topinkova E, Fialova D, Gindin J, van der Roest HG, Landi F, Liperoti R, Bernabei R, Onder G; SHELTER Study. Polypharmacy in nursing home residents with severe cognitive impairment: results from the SHELTER Study. Alzheimers Dement 2013 Sep;9(5):587-93

Colloca G, Tosato M, Vetrano DL, Topinkova E, Fialova D, Gindin J, van der Roest HG, Landi F, Liperoti R, Bernabei R, Onder G, SHELTER project. Inappropriate drugs in elderly patients with severe cognitive impairment: results from the shelter study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46669.

Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Boland B, Rexach L. Drug therapy optimization at the end of life. Drugs Aging. 2012;29:511–21.

Wenger NS, Roth CP, Shekelle P, ACOVE Investigators. Introduction to the assessing care of vulnerable elders-3 quality indicator measurement set. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(Suppl 2):S247–52.

Ray KK, Seshasai SR, Wijesuriya S, et al. Effect of intensive control of glucose on cardiovascular outcomes and death in patients with diabetes mellitus: a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Lancet. 2009;373:1765–72.

Bremer JP, Jauch-Chara K, Hallschmid M, et al. Hypoglycemia unawareness in older compared with middle-aged patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1513–7.

Chelliah A, Burge MR. Hypoglycaemia in elderly patients with diabetes mellitus: causes and strategies for prevention. Drugs Aging. 2004;21:511–30.

Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes Study Group, Gerstein HC, Miller ME, Byington RP, et al. Effects of intensive glucose lowering in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 2008;358:2545–59

Vijan S, Hofer TP, Hayward RA. Estimated benefits of glycemic control in microvascular complications in type 2 diabetes. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:788–95.

Huang ES, Zhang Q, Gandra N, et al. The effect of comorbid illness and functional status on the expected benefits of intensive glucose control in older patients with type 2 diabetes: a decision analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:11–9.

Schwartz AV, Vittinghoff E, Sellmeyer DE. Diabetes-related complications, glycemic control, and falls in older adults. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:391–6.

Monami M, Cresci B, Colombini A. Bone fractures and hypoglycemic treatment in type 2 diabetic patients: a case–control study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:199–203.

Volpato S, Leveille SG, Blaum C. Risk factors for falls in older disabled women with diabetes: the women’s health and aging study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1539–45.

Berlie HD, Garwood CL. Diabetes medications related to an increased risk of falls and fall-related morbidity in the elderly. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:712–7.

Nelson JM, Dufraux K, Cook PF. The relationship between glycemic control and falls in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:2041–4.

Bruce DG, Davis WA, Casey GP, Clarnette RM, Brown SG, Jacobs IG, Almeida OP, Davis TM. Severe hypoglycaemia and cognitive impairment in older patients with diabetes: the Fremantle Diabetes Study. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1808–15.

Feil DG, Rajan M, Soroka O, Tseng CL, Miller DR, Pogach LM. Risk of hypoglycemia in older veterans with dementia and cognitive impairment: implications for practice and policy. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:2263–72.

Whitmer RA, Karter AJ, Yaffe K, Quesenberry CP Jr, Selby JV. Hypoglycemic episodes and risk of dementia in older patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2009;301:1565–72.

Bauduceau B, Doucet J, Bordier L, Garcia C, Dupuy O, Mayaudon H. Hypoglycaemia and dementia in diabetic patients. Diabetes Metab. 2010;36(Suppl 3):S106–11.

Brauner DJ, Muir JC, Sachs GA. Treating nondementia illnesses in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2000;283:3230–5.

Grant RW, Devita NG, Singer DE, Meigs JB. Polypharmacy and medication adherence in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1408–12.

Hewitt J, Smeeth L, Chaturvedi N, Bulpitt CJ, Fletcher AE. Self management and patient understanding of diabetes in the older person. Diabet Med. 2011;28:117–22.

Wu JS, Yang YC, Lu FH. Population-based study on the prevalence and risk factors of orthostatic hypotension in subjects with pre-diabetes and diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:69–74.

Luukinen H, Koski K, Laippala P, Kivelä SL. Prognosis of diastolic and systolic orthostatic hypotension in older persons. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:273–80.

Hiitola P, Enlund H, Kettunen R. Postural changes in blood pressure and the prevalence of orthostatic hypotension among home-dwelling elderly aged 75 years or older. J Hum Hypertens. 2009;23:33–9.

Mangoni AA, Jackson HD. The implications of a growing evidence base for drug use in elderly patients. Part 1. Statins for primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:494–501.

Brugts JJ, Yetgin T, Hoeks SE. The benefits of statins in people without established cardiovascular disease but with cardiovascular risk factors: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2009;338:b2376. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2376.

Heart Protection Study Collaborative, Mihaylova B, Briggs A, Armitage J, Parish S, Gray A, Collins R. Lifetime cost effectiveness of simvastatin in a range of risk groups and age groups derived from a randomised trial of 20,536 people. BMJ 2006;333:1145.

Cholesterol Treatment Trialists' (CTT) Collaborators Efficacy of cholesterol-lowering therapy in 18,686 people with diabetes in 14 randomised trials of statins: a meta-analysis. Lancet 2008;371:117–25.

Holmes HM, Sachs GA, Shega JW, Hougham GW, Cox Hayley D, Dale W. Integrating palliative medicine into the care of persons with advanced dementia: identifying appropriate medication use. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1306–11.

UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) Group. Effect of intensive blood-glucose control with metformin on complications in overweight patients with type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 34) [published erratum appears in Lancet 1998;352:1558]. Lancet. 1998;352:854–65.

Haas L. Management of diabetes mellitus medications in the nursing home. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:209–18.

Neumiller JJ, Setter SM. Pharmacologic management of the older patient with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7:324–42.

Kirpichnikov D, McFarlane SI, Sowers JR. Metformin: an update. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:25–33.

Kapoor JR, Chaudry S, Agostini JV, Foody JA. Systolic hypertension in older persons: how aggressive should treatment be? Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 2006;48:397–406.

Razay G, Williams J, King E, Smith AD, Wilcock G. Blood pressure, dementia and Alzheimer’s disease: the OPTIMA longitudinal study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;28:70–4.

Nilsson SE, Read S, Berg S, Johansson B, Melander A, Lindblad U. Low systolic blood pressure is associated with impaired cognitive function in the oldest old: longitudinal observations in a population-based sample 80 years and older. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2007;19:41–7.

Molander L, Lövheim H, Norman T, Nordström P, Gustafson Y. Lower systolic blood pressure is associated with greater mortality in people aged 85 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1853–9.

Qiu C, Winblad B, Fratiglioni L. The age-dependent relation of blood pressure to cognitive function and dementia. Lancet Neurol. 2005;4:487–99.

Steinman MA, Goldstein MK. When tight blood pressure control is not for everyone: a new model for performance measurement in hypertension. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36:164–72.

Vinyoles E, De la Figuera M, Gonzalez-Segura D. Cognitive function and blood pressure control in hypertensive patients over 60 years of age: COGNIPRES study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2008;24:3331–9.

Cooper LA. A 41-year-old African American man with poorly controlled hypertension: review of patient and physician factors related to hypertension treatment adherence. JAMA. 2009;301:1260–72.

Kassai B, Gueyffier F, Boissel JP, Boutitie F, Cucherat M. Absolute benefit, number needed to treat and gain in life expectancy: which efficacy indices for measuring the treatment benefit? J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:977–82.

Mazza A, Ramazzina E, Cuppini S, Armigliato M, Schiavon L, Rossetti C, Marzolo M, Santoro G, Ravenni R, Zuin M, Zorzan S, Rubello D, Casiglia E. Antihypertensive treatment in the elderly and very elderly: always “the lower, the better?”. Int J Hypertens. 2012;2012:590683.

Montgomery AA, Fahey T, Ben-Shlomo Y, Harding J. The influence of absolute cardiovascular risk, patient utilities, and costs on the decision to treat hypertension: a Markov decision analysis. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1753–9.

Woolcott JC, Richardson KJ, Wiens MO, Patel B, Marin J, Khan KM, Marra CA. Meta-analysis of the impact of 9 medication classes on falls in elderly persons. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1952–60.

Kamaruzzaman S, Watt H, Carson C, Ebrahim S. The association between orthostatic hypotension and medication use in the British Women’s Heart and Health Study. Age Ageing. 2010;39:51–6.

Tinetti ME. Clinical practice: preventing falls in elderly persons. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:42–9.

Butt DA, Mamdani M, Austin PC, Tu K, Gomes T, Glazier RH. The risk of hip fracture after initiating antihypertensive drugs in the elderly. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1739–44.

Weir RA, McMurray JJ, Puu M, Solomon SD, Olofsson B, Granger CB, Yusuf S, Michelson EL, Swedberg K, Pfeffer MA, CHARM Investigators. Efficacy and tolerability of adding an angiotensin receptor blocker in patients with heart failure already receiving an angiotensin-converting inhibitor plus aldosterone antagonist, with or without a beta blocker. Findings from the Candesartan in Heart failure: Assessment of Reduction in Mortality and morbidity (CHARM)-Added trial. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10:157–63.

Jneid H, Moukarbel GV, Dawson B, Hajjar RJ, Francis GS. Combining neuroendocrine inhibitors in heart failure: reflections on safety and efficacy. Am J Med 2007;120:1090.e1–8.

Cheng JW, Nayar M. A review of heart failure management in the elderly population. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2009;7:233–49.

Cherubini A, Oristrell J, Pla X, Ruggiero C, Ferretti R, Diestre G, Clarfield AM, Crome P, Hertogh C, Lesauskaite V, Prada GI, Szczerbinska K, Topinkova E, Sinclair-Cohen J, Edbrooke D, Mills GH. The persistent exclusion of older patients from ongoing clinical trials regarding heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:550–6.

Leipzig RM, Cumming RG, Tinetti ME. Drugs and falls in older people: a systematic review and meta-analysis: II. Cardiac and analgesic drugs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:40–50.

Mehagnoul-Schipper DJ, Colier WN, Hoefnagels WH, Verheugt FW, Jansen RW. Effects of furosemide versus captopril on postprandial and orthostatic blood pressure and on cerebral oxygenation in patients > or = 70 years of age with heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90:596–600.

Ahmed A, Husain A, Love TE, Gambassi G, Dell’Italia LJ, Francis GS, Gheorghiade M, Allman RM, Meleth S, Bourge RC. Heart failure, chronic diuretic use, and increase in mortality and hospitalization: an observational study using propensity score methods. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:1431–9.

Abdel-Qadir HM, Tu JV, Yun L, Austin PC, Newton GE, Lee DS. Diuretic dose and long-term outcomes in elderly patients with heart failure after hospitalization. Am Heart J. 2010;160:264–71.

Eshaghian S, Horwich TB, Fonarow GC. Relation of loop diuretic dose to mortality in advanced heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2006;97:1759–64.

Lim LS, Fink HA, Blackwell T, Taylor BC, Ensrud KE. Loop diuretic use and rates of hip bone loss and risk of falls and fractures in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:855–62.

Lee DS, Ghosh N, Floras JS, Newton GE, Austin PC, Wang X, Liu PP, Stukel TA, Tu JV. Association of blood pressure at hospital discharge with mortality in patients diagnosed with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:616–23.

Muzzarelli S, Leibundgut G, Maeder MT, Rickli H, Handschin R, Gutmann M, Jeker U, Buser P, Pfisterer M, Brunner-La Rocca HP, TIME-CHF Investigators. Predictors of early readmission or death in elderly patients with heart failure. Am Heart J. 2010;160:308–14.

Banach M, Bhatia V, Feller MA, Mujib M, Desai RV, Ahmed MI, Guichard JL, Aban I, Love TE, Aronow WS, White M, Deedwania P, Fonarow G, Ahmed A. Relation of baseline systolic blood pressure and long-term outcomes in ambulatory patients with chronic mild to moderate heart failure. Am J Cardiol. 2011;107:1208–14.

Desai RV, Banach M, Ahmed MI, Mujib M, Aban I, Love TE, White M, Fonarow G, Deedwania P, Aronow WS, Ahmed A. Impact of baseline systolic blood pressure on long-term outcomes in patients with advanced chronic systolic heart failure (insights from the BEST trial). Am J Cardiol. 2010;106:221–7.

Vidán MT, Bueno H, Wang Y, Schreiner G, Ross JS, Chen J, Krumholz HM. The relationship between systolic blood pressure on admission and mortality in older patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:148–55.

Gheorghiade M, Abraham WT, Albert NM, Greenberg BH, O’Connor CM, She L, Stough WG, Yancy CW, Young JB, Fonarow GC, OPTIMIZE-HF Investigators and Coordinators. Systolic blood pressure at admission, clinical characteristics, and outcomes in patients hospitalized with acute heart failure. JAMA. 2006;296:2217–26.

Qiu C, Winblad B, Marengoni A, Klarin I, Fastbom J, Fratiglioni L. Heart failure and risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease: a population-based cohort study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1003–8.

Zuccalà G, Onder G, Pedone C, Carosella L, Pahor M, Bernabei R, Cocchi A, GIFA-ONLUS Study Group [Gruppo Italiano di Farmacoepidemiologia nell'Anziano]. Hypotension and cognitive impairment: selective association in patients with heart failure. Neurology. 2001;11(57):1986–92.

Spiess JL. Can I stop the warfarin? A review of the risks and benefits of discontinuing anticoagulation. J Palliat Med. 2009;12:83–7.

Kierner KA, Gartner V, Schwarz M, Watzke HH. Use of thromboprophylaxis in palliative care patients: a survey among experts in palliative care, oncology, intensive care, and anticoagulation. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2008;25:127–31.

Lurie Y, Loebstein R, Kurnik D, Almog S, Halkin H. Warfarin and vitamin K intake in the era of pharmacogenetics. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;70:164–70.

Sebastian JL, Tresch DD. Use of oral anticoagulants in older patients. Drugs Aging. 2000;16:409–35.

Ansell J, Hirsh J, Hylek E, Jacobson A, Crowther M, Palareti G. Pharmacology and management of the vitamin K antagonists: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition). Chest. 2008;133:160–98.

Kwok CS, Loke YK, Hale R, Potter JF, Myint PK. Atrial fibrillation and incidence of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2011;76:914–22.

Rose AJ, Hylek EM, Ozonoff A, Ash AS, Reisman JI, Berlowitz DR. Patient characteristics associated with oral anticoagulation control: results of the Veterans AffaiRs Study to Improve Anticoagulation (VARIA). J Thromb Haemost. 2010;8:2182–91.

van Deelen BA, van den Bemt PM, Egberts TC, van 't Hoff A, Maas HA. Cognitive impairment as determinant for sub-optimal control of oral anticoagulation treatment in elderly patients with atrial fibrillation. Drugs Aging. 2005;22:353–60.

Flaker GC, Pogue J, Yusuf S, Pfeffer MA, Goldhaber SZ, Granger CB, Anand IS, Hart R, Connolly SJ; Atrial Fibrillation Clopidogrel Trial With Irbesartan for Prevention of Vascular Events (ACTIVE) Investigators. Cognitive function and anticoagulation control in patients with atrial fibrillation. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2010;3:277–83.

Gage BF, Birman-Deych E, Kerzner R, Radford MJ, Nilasena DS, Rich MW. Incidence of intracranial hemorrhage in patients with atrial fibrillation who are prone to fall. Am J Med. 2005;118:612–7.

Gage BF, Yan Y, Milligan PE, Waterman AD, Culverhouse R, Rich MW, Radford MJ. Clinical classification schemes for predicting hemorrhage: results from the National Registry of Atrial Fibrillation (NRAF). Am Heart J. 2006;151(3):713–9.

Man-Son-Hing M, Nichol G, Lau A, Laupacis A. Choosing antithrombotic therapy for elderly patients with atrial fibrillation who are at risk for falls. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(7):677–85.

Sellers MB, Newby LK. Atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation, fall risk, and outcomes in elderly patients. Am Heart J. 2011;161(2):241–6.

Kaplan RC, Heckbert SR, Koepsell TD, Furberg CD, Polak JF, Schoen RE, Psaty BM. Risk factors for hospitalized gastrointestinal bleeding among older persons. Cardiovascular Health Study Investigators. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:126–33.

Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation study: final results. Circulation 1991;84:527–39

Secondary prevention in non-rheumatic atrial fibrillation after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke. EAFT (European Atrial Fibrillation Trial) Study Group. Lancet 1993;342:1255–62

Diug B, Evans S, Lowthian J, Maxwell E, Dooley M, Street A, Wolfe R, Cameron P, McNeil J. The unrecognized psychosocial factors contributing to bleeding risk in warfarin therapy. Stroke. 2011;42:2866–71.

Arlt S, Lindner R, Rösler A, von Renteln-Kruse W. Adherence to medication in patients with dementia: predictors and strategies for improvement. Drugs Aging. 2008;25:1033–47.

Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, Kirby A, Sourjina T, Peto R, Collins R, Simes R, Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaborators. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–78.

Verwoert GC, Mattace-Raso FU, Hofman A, Heeringa J, Stricker BH, Breteler MM, Witteman JC. Orthostatic hypotension and risk of cardiovascular disease in elderly people: the Rotterdam study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:1816–20.

Luukinen H, Koski K, Laippala P, Airaksinen KE. Orthostatic hypotension and the risk of myocardial infarction in the home-dwelling elderly. J Intern Med. 2004;255:486–93.

Søgaard P, Thygesen K. Potential proischemic effect of early enalapril in hypotension-prone patients with acute myocardial infarction. The CONSENSUS II Holter Substudy Group. Cardiology. 1997;88:285–91.

Avanzini F, Ferrario G, Santoro L, Peci P, Giani P, Santoro E, Franzosi MG, Tognoni G, Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell’Infarto miocardico-3 Investigators. Risks and benefits of early treatment of acute myocardial infarction with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in patients with a history of arterial hypertension: analysis of the GISSI-3 database. Am Heart J. 2002;144:1018–25.

Acknowledgments

The CRIME project was funded by a grant from the Italian Ministry of Labour, Health and Social Policy (Bando Giovani Ricercatori 2007, convenzione no. 4). The authors have no conflicts of interest that are directly relevant to this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: List of Guidelines Examined

1.1 Heart Failure

Hunt SA, Abraham WT, Chin MH, Feldman AM, Francis GS, Ganiats TG, Jessup M, Konstam MA, Mancini DM, Michl K, Oates JA, Rahko PS, Silver MA, Stevenson LW, Yancy CW; American College of Cardiology Foundation; American Heart Association. 2009 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the diagnosis and management of heart failure in adults. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines Developed in Collaboration With the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009 Apr 14;53(15):e1–e90.

McMurray JJ, Adamopoulos S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Böhm M, Dickstein K, Falk V, Filippatos G, Fonseca C, Gomez-Sanchez MA, Jaarsma T, Køber L, Lip GY, Maggioni AP, Parkhomenko A, Pieske BM, Popescu BA, Rønnevik PK, Rutten FH, Schwitter J, Seferovic P, Stepinska J, Trindade PT, Voors AA, Zannad F, Zeiher A; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 2012 Jul;33(14):1787–847.

1.2 Hypertension

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, Roccella EJ; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure; National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report. JAMA 2003 May 21;289(19):2560–72.

Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Cifkova R, Fagard R, Germano G, Grassi G, Heagerty AM, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Narkiewicz K, Ruilope L, Rynkiewicz A, Schmieder RE, Boudier HA, Zanchetti A, Vahanian A, Camm J, De Caterina R, Dean V, Dickstein K, Filippatos G, Funck-Brentano C, Hellemans I, Kristensen SD, McGregor K, Sechtem U, Silber S, Tendera M, Widimsky P, Zamorano JL, Erdine S, Kiowski W, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Lindholm LH, Viigimaa M, Adamopoulos S, Agabiti-Rosei E, Ambrosioni E, Bertomeu V, Clement D, Erdine S, Farsang C, Gaita D, Lip G, Mallion JM, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, O’Brien E, Ponikowski P, Redon J, Ruschitzka F, Tamargo J, van Zwieten P, Waeber B, Williams B; Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension; European Society of Cardiology. 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). J Hypertens 2007 Jun;25(6):1105–87.

1.3 Atrial Fibrillation

Fuster V, Rydén LE, Cannom DS, Crijns HJ, Curtis AB, Ellenbogen KA, Halperin JL, Kay GN, Le Huezey JY, Lowe JE, Olsson SB, Prystowsky EN, Tamargo JL, Wann LS. 2011 ACCF/AHA/HRS focused updates incorporated into the ACC/AHA/ESC 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines developed in partnership with the European Society of Cardiology and in collaboration with the European Heart Rhythm Association and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011 Mar 15;57(11):e101–98.

European Heart Rhythm Association; European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery, Camm AJ, Kirchhof P, Lip GY, Schotten U, Savelieva I, Ernst S, Van Gelder IC, Al-Attar N, Hindricks G, Prendergast B, Heidbuchel H, Alfieri O, Angelini A, Atar D, Colonna P, De Caterina R, De Sutter J, Goette A, Gorenek B, Heldal M, Hohloser SH, Kolh P, Le Heuzey JY, Ponikowski P, Rutten FH. Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: the Task Force for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J 2010 Oct;31(19):2369–429.

1.4 Coronary Artery Disease

Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, Berra K, Blankenship JC, Dallas AP, Douglas PS, Foody JM, Gerber TC, Hinderliter AL, King SB 3rd, Kligfield PD, Krumholz HM, Kwong RY, Lim MJ, Linderbaum JA, Mack MJ, Munger MA, Prager RL, Sabik JF, Shaw LJ, Sikkema JD, Smith CR Jr, Smith SC Jr, Spertus JA, Williams SV; American College of Cardiology Foundation. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association task force on practice guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation 2012 Dec 18;126(25):3097–137.

Fox K, Garcia MA, Ardissino D, Buszman P, Camici PG, Crea F, Daly C, De Backer G, Hjemdahl P, Lopez-Sendon J, Marco J, Morais J, Pepper J, Sechtem U, Simoons M, Thygesen K, Priori SG, Blanc JJ, Budaj A, Camm J, Dean V, Deckers J, Dickstein K,Lekakis J, McGregor K, Metra M, Morais J, Osterspey A, Tamargo J, Zamorano JL; Task Force on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology; ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines (CPG). Guidelines on the management of stable angina pectoris: executive summary: The Task Force on the Management of Stable Angina Pectoris of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J 2006 Jun;27(11):1341–81.

1.5 Diabetes

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes–2012. Diabetes Care 2012 Jan;35 Suppl 1:S11–63.

Brown AF, Mangione CM, Saliba D, Sarkisian CA; California Healthcare Foundation/American Geriatrics Society Panel on Improving Care for Elders with Diabetes. Guidelines for improving the care of the older person with diabetes mellitus. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003 May;51(5 Suppl Guidelines):S265–80.

Appendix 2: Names and Affiliations of Experts

Name | Affiliation | Country |

|---|---|---|

Antonio Cherubini | University of Perugia | Italy |

Stefano Volpato | University of Ferrara | Italy |

Andrea Corsonello | Italian National Research Center on Aging (INRCA) | Italy |

Eva Topinkova | Prague University | Czech Republic |

Mirko Petrovic | Ghent University | Belgium |

Tischa Van der Cammen | Erasmus Medical Center | The Netherlands |

Dorom Garfinkel | Shoham Geriatric Medical Center | Israel |

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Onder, G., Landi, F., Fusco, D. et al. Recommendations to Prescribe in Complex Older Adults: Results of the CRIteria to Assess Appropriate Medication Use Among Elderly Complex Patients (CRIME) Project. Drugs Aging 31, 33–45 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0134-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40266-013-0134-4