Abstract

Parents of children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) risk higher levels of stress and a lower quality of life compared to parents of typically developing children. Few parent training programs focus on parenting outcomes, and few authors evaluate the implementation fidelity of their program. A systematic review was conducted to target studies assessing the effects of group training programs on the stress levels or quality of life of parents of children with ASD as well as the implementation fidelity. A total of 12 studies were identified. Findings suggest that mindfulness could be a promising parent training tool to improve the well-being of parents of children with ASD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is now considered a neurodevelopmental disorder that is characterized by both difficulties in communication and social interactions and equally by restricted/repetitive interests, behaviors, and activities, including sensory sensitivities (American Psychiatric Association 2013). The prevalence of ASD in the world today is estimated to affect 6 in every 1000 children, and the care of people with ASD is a major public health issue (Bearss et al. 2015a, 2015b). Approximately 70% of people with ASD also present at least one other characteristic or associated disorder: neurodevelopmental, medical, genetic, or psychiatric conditions (NICE 2013). Certain activities of daily life of people with ASD can equally be affected, such as eating, toilet training, or sleep (NICE 2013). In addition, other domains of daily life can also be negatively impacted, such as social participation, financial independence, academic success (Robertson 2010), professional success, and personal relationships (Mazurek 2014). These can have major repercussions, not only on themselves but also on their family, although not all people with ASD encounter such difficulties (NICE 2013).

Quality of Life and Stress of Parents of Children with ASD

Today, it is well demonstrated that parents of children with ASD present significantly higher levels of stress when compared to parents of typically developing children [see Bonis 2016 for a review and Hayes and Watson 2013 for a meta-analysis] or present other developmental disorders, as seen, for example, among parents of children with Down syndrome (NICE 2013), other mental disorders such as mood disorders, or chronic illnesses (Barroso et al. 2017). It has equally been shown that the stress experienced by parents impacts, in turn, their conjugal relations, as well as their capacity to effectively manage the education of their child (Bonis 2016).

Regardless of country or culture, the quality of life of parents of children with ASD is lower than parents of typically developing children (Eapen and Guan 2016; Vasilopoulou and Nisbet 2016), especially concerning the physical domain (Vasilopoulou and Nisbet 2016).

Consequently, the psychological and social impact on families must be the primary focus of researchers and clinicians working with families of people with ASD, in order to offer them valuable support that is adapted to their personal needs.

Training Programs for Parents of Children with ASD

The participation of parents of children with ASD in intervention programs is essential (Cappe et al. 2011; Goussot et al. 2012; NICE 2013; Parsons et al. 2017; Pfeiffer et al. 2016; Strauss et al. 2013; Klinger et al. 2013). In fact, during the last several years, we have been witnessing an increased interest in parent training programs (Bearss et al. 2015a). Parents are often those demanding this type of intervention, and they are generally satisfied by their experience (Beaudoin et al. 2014; Benn et al. 2012; Dababnah and Parish 2016a, 2016b; Derguy et al. 2018; Ilg et al. 2017, 2018; Kuravackel et al. 2018; Mazzucchelli et al. 2018; Papageorgiou & Kalyva 2010, cited by Schultz et al. 2012; Parsons et al. 2017; Schultz et al. 2012). The interventions proposed today in the field of autism are mostly parent-mediated, especially among families with children at preschool age (Pickles et al. 2016).

Originally, parent training programs mainly targeted parents of children presenting challenging behaviors. Their beneficial effects were demonstrated on outcomes regarding parents’ level of knowledge and their capacity to manage their child’s behavior. These programs also had potential to reduce the parents’ stress and increase their sense of competence (Schultz et al. 2011). Among child mental health services, the term parent training is a synonym of parent-focused training, which is an evidence-based treatment for typically developing children with challenging behaviors (Bearss et al. 2015a, 2015b). By contrast, in the field of autism, the term parent training is associated with a variety of treatments that may or may not share common characteristics (Bearss et al. 2015a, 2015b). The complexity of ASD as well as the various targets of intervention may explain the ambiguity of the term parent training within the scientific literature (Bearss et al. 2015a, 2015b). In addition to being called parent training, the literature concerning treatments that focus on the parents of children with ASD includes other terminologies, such as parent education, parent-implemented, parent-mediated, and caregiver-mediated. All of these programs represent a variety of interventions with diverse treatment designs and objectives (Bearss et al. 2015a, 2015b; Preece and Trajkovski 2017). Although all of these interventions try to help parents foster more positive interactions and increase parental knowledge and skills as well as confidence in managing problem behaviors, their theoretical approaches vary considerably (O’Nions et al. 2018).

Bearss et al. (2015a, 2015b) distinguish between two types of training programs for parents of children with ASD: programs providing parental support that favor the acquisition of knowledge about autism (parent support) and programs that actively involve the parents by teaching them specific skills in order to promote behavioral change among their children (parent-mediated intervention (PMI)). The first type (parent support) targets parental knowledge resulting in secondary and indirect benefits for the child with ASD. Among the parent support programs, the authors distinguish between care coordination and psychoeducation. While the second type (PMI) targets the acquisition of specific parenting skills while directly involving the child. Hence, the child is a direct beneficiary of the intervention in which the parent is the mediator. Furthermore, among the PMI programs, the authors distinguish two subtypes: PMIs that target the core symptoms of autism and PMIs that target challenging behaviors (tantrums, aggressive behaviors), difficulties following daily routines, hyperactivity, sleep disturbance, toileting problems, etc. The PMIs can then be divided into primary and complementary interventions depending on who mainly implements specific techniques with the child. In the primary intervention, the parent is the principle agent of change, whereas in the complementary intervention, the therapists work mainly with the child and the parent is taught certain techniques by a member of the team. Bearss et al. (2015a, 2015b) report that interventions may also vary in terms of their design (the more current setup involves therapists coaching parents during parent–child interactions), their intensity (1–25 h per week), the location of the implementation (clinic, school, home, or, more recently, delivery via telehealth), their duration (1 week to 2 years), and the age of the child (preschool to adolescence).

There are already many systematic reviews or meta-analyses that support the use of parent training in the field of autism. Certain focus on interventions targeting skills related to the child, like generalization and the maintenance of social communication skills (Hong et al. 2018), challenging behaviors (Postorino et al. 2017), or restricted and repetitive behaviors (Harrop 2015). Others focus on interventions targeting all outcomes related to the parents, children, and family (Beaudoin et al. 2014; Oono et al. 2013; Patterson et al. 2012; McConachie and Diggle 2007; Schultz et al. 2011). There are also more specific systematic reviews that analyze the effects of training parents of only school-age children (Black and Therrien 2018) as well as a review evaluating parent-mediated intervention training delivered remotely (Parsons et al. 2017).

State of Current Research

Current research in the domain of training programs for parents of children with ASD is questionable for at least three reasons. First, the majority of parent training programs studied to date focus on the outcomes directly concerning the child but do not assess much of their impact on parenting issues (Wainer et al. 2017). Yet, diminishing parent stress and increasing quality of life are constant concerns of families of children with ASD (Hsiao et al. 2017). It is therefore important to take into account the effects of interventions on these priority variables for parents (Leadbitter et al. 2018). Moreover, given that the family is one of the pillars of our society, it is essential to study factors at the origin of family stress (Pastor-Cerezuela et al. 2016). Also, a better understanding of the quality of life of parents of children with ASD is crucial to identify those susceptible to stress and to clarify the areas requiring support (Vasilopoulou and Nisbet 2016). For example, two reviews specifically evaluate the effects of interventions involving the parents of children with ASD in different aspects of their mental health: measures of stress, anxiety, depression, quality of life, coping, subjective well-being, and self-efficacy [see Catalano et al. 2018 for a systematic review and Da Paz and Wallander 2017 for a narrative review].

Second, few authors propose to evaluate the implementation fidelity of their program. Thus, Schultz et al. (2011) did not identify any study evaluating the implementation fidelity of a program in their systematic review. However, implementation fidelity data is important to ensure that the program as defined in the manual has been implemented accurately and consistently (Alain and Dessureault 2009; Durlak 2010; Oono et al. 2013). This allows results to be correctly interpreted and programs to be replicable (Schultz et al. 2011). Finally, to evaluate the quality of the implementation, Durlak and DuPre (2008) recommend that every study should reflect the participants’ responsiveness, which evaluates if the program stimulates their interest and holds their attention; this is related to what is called the social validity of an intervention. This is divided into three levels that can be validated by society: the social significance of the objectives, the adequacy of the procedures, and the social importance of the effects (Clément and Schaeffer 2010).

Third, certain parent training programs are only evaluated on the basis of individual sessions (see, for example, Bradshaw et al. 2018; Goldman et al. 2017; Iadarola et al. 2018; Ibanez et al. 2018; Ingersoll et al. 2016; Kasari et al. 2015; Lecavalier et al. 2018; Reed et al. 2013; Poslawsky et al. 2015; Tellegen and Sanders 2014). This does not allow interventions to reach a large number of parents as is the case with group training programs (Schultz et al. 2011). When parent training programs are proposed in groups, the cost-effective ratio is more advantageous (Bearss et al. 2015a, 2015b; Brookman-Frazee et al. 2006), which is an important element for choosing an intervention (Shepherd et al. 2018). Furthermore, the social support provided by other parents of children with ASD in these groups is a factor that can improve parental well-being (Catalano et al. 2018; Derguy et al. 2015; Hock et al. 2015; Lovell et al. 2012; Samadi et al. 2012).

Overall, group sessions and assessing implementation fidelity are judged to be decisive factors for evaluating parent training programs of typically developing children (Matthews and Hudson 2001) as well as children with ASD (Schultz et al. 2011).

Objectives of the Present Study

The primary objective of this systematic review is to identify studies seeking to evaluate the implementation fidelity and social validity of group training programs for parents of children with ASD as well as the effect of these interventions on parental stress levels and quality of life. The second objective is to provide an overview of the different interventions proposed to groups of parents of children with ASD. The third objective is to provide an overview of the tools, methods, and findings used to evaluate parents’ quality of life, stress, and the programs’ implementation fidelity and social validity.

Methods

This review followed the PRISMA standards for reporting (Liberati et al. 2009).

Eligibility Criteria

Only studies published in English or French in a peer-reviewed journal were retained. The studies had to include an evaluation of a parent training program, either a qualitative or quantitative evaluation of program implementation fidelity, at least one quantitative evaluation regarding the effects on parental stress levels and quality of life, and a minimum of two parents per group. The presence of a control group was optional. The participants had to be the parents of a child with ASD of any age having received a diagnosis of ASD or PDD corresponding to the criteria of international classifications (CIM-10, DSM-IV-TR, or DSM-5). The diagnosis had to either be explicitly confirmed during the research procedure, extracted from the participants’ medical file, or obtained through other reliable sources (e.g., parental reports).

Information Sources and Research Strategies

An electronic search was conducted by one author (JL) in December 2018 and by another author (ND) in February 2019. The research was limited to the period 2011 to November 2018 in the databases PubMed, PsycINFO via the access provider EBSCOhost, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC), PubPsych, and Science Direct. Studies were included from 2011 as Schultz et al. (2011) did not identify in their systematic review any studies evaluating the implementation fidelity of training programs created for parents of children with ASD. The following keywords were used: autism, ASD, parent training, parent education, caregiver training, caregiver education, family training, parent-implemented, parent-mediated, caregiver-mediated, program, stress and quality of life. These terms were searched using Boolean operators and free-text terms. The algorithm used in each database was (autis* OR ASD) AND (“parent training” OR “parent education” OR “caregiver training” OR “caregiver education” OR “family training” OR program* OR “parent-implemented” OR “parent-mediated” OR “caregiver-mediated”) AND (stress OR “quality of life”). We applied this algorithm to title and abstract in PubMed, to abstracts for PsycINFO-EBSCO, to all fields for ERIC and PubPsych, and to title, abstract, or keywords for Science Direct. The bibliographies of examined articles were also searched in order to identify other suitable studies.

Study Selection

Two of the authors (JL and ND) independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts in order to determine whether they met inclusion criteria. This resulted in a 95% researcher agreement rate. A third author (EC) then reviewed the full texts of disputed articles in order to determine eligibility.

Data Extraction and Collection

Both authors (JL and ND) followed the same guidelines (Matthews and Hudson 2001; Schultz et al. 2011) to extract data concerning the studies’ various characteristics and programs, such as (1) the type of program proposed to parents; (2) the number of participants per group; (3) the duration of implementation, frequency, and duration of each session; (4) tools used to evaluate the program’s effect on the stress levels and/or quality of life of parents; (5) children’s age; (6) whether or not the child is directly involved in the intervention in addition to parent training; (7) whether or not there is a contribution of knowledge as well as teaching parents specific skills; (8) study design; (9) whether or not there is a follow-up and, if so, the duration of this follow-up; and (10) the methodological quality and level of evidence.

The following data used to evaluate the implementation fidelity of programs were extracted based on the following recommendations by Clément and Schaeffer (2010), Durlak (2010), and Durlak and DuPre (2008): (1) research tools, (2) methods, (3) evaluation frequency, (4) persons who carried out the evaluation, (5) results, and (6) variables retained for evaluating the interventions’ social validity. The findings from both authors were then discussed and reviewed in order to ensure consistency.

Evaluation of the Methodological Quality and Level of Evidence of Studies

The STROBE guidelines (von Elm et al. 2008) were used for evaluating each study’s methodological quality. A total of 22 items in the guideline’s control list were rated as such: a score of 1 was attributed if all the item’s criteria were respected, 0.5 if the criteria were partially respected, and 0 if none of the criteria was found in the study. The global evaluation of each study was obtained by transforming the total score into a percentage of criteria respected.

The level of evidence was determined using the hierarchy of evidence as outlined in the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) guidelines (1999): levels varied between I (the highest level of evidence) and IV (the lowest level of evidence).

Risk of Bias Inherent in Each Randomized Controlled Trials

Both authors (JL and ND) independently evaluated the risk of bias inherent in each randomized controlled trial (RCT) with the help of the risk of bias tool as recommended by the Munder and Barth (2017), which includes these seven domains of bias: (1) the random sequence generation, (2) the allocation concealment, (3) performance bias, (4) detection bias, (5) attrition bias, (6) reporting bias, and (7) treatment implementation. For each domain, the risk of bias was evaluated as low (+), high (−), or unclear (?).

Risk of Bias across Studies

None of the researchers were authors of any of the included published studies. Hence, there was no bias of study selection in this systematic review.

Results

Study Selection

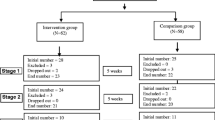

The PRISMA diagram is presented in Fig. 1. Of the 1269 abstracts identified, 1172 were rejected at abstract review, and 97 available full texts were assessed. Of these, 85 did not meet our inclusion criteria, resulting in the inclusion of 12 studies, 2 of which were additional references found through reference checking. The two articles by Studies of Dababnah and Parish (2016a, 2016b) were based on the outcomes from one study sample, so they were combined for reporting and discussion throughout this paper.

Characteristics of Included Studies and Their Programs

The characteristics of the included studies and their programs are presented in Table 1.

Study Participants

Two of the twelve studies selected for this review included not only parents of children on the autism spectrum but also parents of children with other developmental disorders (Benn et al. 2012; Dykens et al. 2014). The number of parents per group was not always specified by authors; however, the groups never exceeded 15 participants. The number of parent groups generally varied between 1 (Benn et al. 2012; Mazzucchelli et al. 2018) and 6 (Dykens et al. 2014). Three studies only included mothers (Dykens et al. 2014; Roberts et al. 2011; Schultz et al. 2012), and all the other studies included a minority of fathers compared to the number of mothers, except for studies of Dababnah and Parish (2016a, 2016b) in which there were a higher number of fathers than mothers. Kuravackel et al. (2018) and Radley et al. (2014) did not specify the mother-to-father ratio.

Interventions

The duration of implementation varied between 1 month (Matthews et al. 2018) and 12 months (Roberts et al. 2011) across studies. The duration and frequency of sessions also varied between programs. The sessions were once or twice a week and never exceeded 4 h (Roberts et al. 2011). In addition to group sessions, some programs also offered individual face-to-face sessions (Kuravackel et al. 2018), telephone sessions (Mazzucchelli et al. 2018), introduction sessions (Matthews et al. 2018; Radley et al. 2014), or complementary sessions (Benn et al. 2012). In this review, one study presented a program that notably combined parent-facilitated training groups in parallel to peer-mediated skill sessions involving typically developing peers (Radley et al. 2014).

All included studies proposed programs that taught techniques from the third wave of cognitive and behavioral therapies to parents. Indeed, there is an international consensus for using behavioral science to manage behaviors and difficulties associated with autism (for example, cognitive and behavioral therapy as well as applied behavior analysis are recommended by health authorities in France, the UK, Belgium, or New Zealand to manage and support individuals on the autism spectrum). Among the twelve included studies, six offered parent training programs based either primarily (Benn et al. 2012; Dykens et al. 2014; Ferraioli and Harris 2013) or partially (Dababnah and Parish 2016a, 2016b; Kuravackel et al. 2018) on learning mindfulness techniques. Programs based primarily on learning mindfulness techniques were quite different from the others, as parents were taught different skills to those directly linked to the education of their child.

In addition to training skills, two other programs also provided information on autism (Kuravackel et al. 2018; Matthews et al. 2018). Indeed, Kaminski, Valle, Filene, and Boyle (2008), quoted by Schultz et al. (2011), highlight that teaching parents specific skills is correlated with more positive outcomes than just providing them with general knowledge. Thus, Schultz et al. (2011) suggest that only parent programs offering training of specific skills should be considered, rather than programs focusing solely on knowledge acquisition. Nevertheless, certain authors indicate that parents of children with ASD give high priority to information about their children’s disabilities and often ask for access to parent education as a means of obtaining information on autism (Schultz et al. 2012). More generally, it is important to consider the characteristics and demands of people with ASD and their parents, regarding the variables that these programs should target (Clifford and Minnes 2013; MacCormack 2017; Schultz et al. 2011). It is unlikely that one intervention responds to the needs of all children and their parents, as well as being equally unlikely that all parents learn in the same manner (Siller et al. 2013).

In parallel to parent training, professionals directly taught children certain skills among five programs (Karst et al. 2015; Matthews et al. 2018; Radley et al. 2014; Roberts et al. 2011; Schultz et al. 2012).

All studies provided a more or less detailed description of the program’s curriculum. As suggested by Schultz et al. (2011), it is unlikely for studies to evaluate implementation fidelity without a standardized protocol.

Finally, two studies proposed to evaluate the effects of a program by implementing control groups to compare two conditions: either face-to-face in comparison to telehealth (Kuravackel et al. 2018) or institution compared to home-based intervention (Roberts et al. 2011). With regard to the study by Kuravackel et al. (2018), the authors showed that teaching skills to parental groups via telehealth did not significantly impact therapeutic alliance, social validity, implementation fidelity, or parental variables related to the face-to-face condition. This supports the use of remote training programs for parental groups, with the objective of reducing costs and improving accessibility (Schultz et al. 2011). Concerning the study of Roberts et al. (2011), the authors showed that group intervention in an institutional setting provides better results than individual interventions carried out at home, which confirms the pertinence of group training compared to individual training.

Study Design

Of the twelve studies included, five proposed a RCT design (Benn et al. 2012; Karst et al. 2015; Kuravackel et al. 2018; Roberts et al. 2011; Schultz et al. 2012), of which one included a follow-up at 2 months (Benn et al. 2012). Other research designs among the included studies consisted a randomized trial with an untreated control group (Dykens et al. 2014; Ferraioli and Harris 2013), a mixed methods design with no comparison group (Dababnah and Parish 2016a, 2016b), an iterative pretest–posttest control group design (Kuravackel et al. 2018), a pre–post comparison of treatment and control groups (Matthews et al. 2018), and a pretest–posttest single group (Radley et al. 2014).

Outcomes

All studies evaluated parents’ stress levels using different tools, the most frequent being the Parenting Stress Index (either the third or fourth edition of this tool in the short or full version), which was used in eight of the twelve studies. Parents’ stress levels were not significantly reduced by the parent program among four studies (Karst et al. 2015; Matthews et al. 2018; Mazzucchelli et al. 2018; Roberts et al. 2011). Mazzucchelli et al. (2018) showed, nevertheless, a unique and significant effect at follow-up. It is worth mentioning that among the other eight studies showing a significant effect of the program on the reduction of parental stress levels, six offered an intervention based primarily or partially on mindfulness training. Only Radley et al. (2014) and Schultz et al. (2012) showed that their program significantly reduced parental stress levels without using this type of training.

Two studies also evaluated parental quality of life, using either the Ryff Scales of Psychological Well-Being and Life Satisfaction Scale (Dykens et al. 2014) or the Beach Family Quality of Life Questionnaire (Roberts et al. 2011). Roberts et al. (2011) did not observe a significant effect of the program in improving parental quality of life. Dykens et al. (2014) observed a significant improvement in the scores of the Ryff Scales of Psychological Well-Being only at follow-up (but not at posttest) and observed a significant improvement of scores on the Life Satisfaction Scale only at posttest (but not at follow-up).

Implementation Process Assessment

Table 2 presents the data on the assessment of the implementation process.

The research tools and methods used to evaluate program implementation vary between studies. Nevertheless, an observation checklist was the most employed tool for verifying that no program components had been omitted. Therefore, they primarily evaluated the program’s contents. Hence, evaluations were binary, depending on the absence or presence of items presented in the manual. Although one study did not specify the used measuring tool (Karst et al. 2015) and two other studies only provided observation feedbacks without specifying the measuring tools (Benn et al. 2012; Dykens et al. 2014), it should also be noted that the study by Schultz et al. (2012) was the only one to have evaluated both the implementation process and content, and Radley et al. (2014) was the only study to propose a semi-structured questionnaire in addition to an observation checklist.

Observations were made either directly during sessions (Benn et al. 2012; Dababnah and Parish 2016a, 2016b; Karst et al. 2015; Kuravackel et al. 2018; Mazzucchelli et al. 2018; Radley et al. 2014; Roberts et al. 2011; Schultz et al. 2012) or from videos (Ferraioli and Harris 2013; Matthews et al. 2018), by one or multiple observers. In this last case, an interobserver agreement was sometimes calculated (Matthews et al. 2018; Mazzucchelli et al. 2018; Schultz et al. 2012). It is also worth noting that in the research of Kuravackel et al. (2018), the observer was a parent. Among the studies, the implementation process of sessions was evaluated either fully (Benn et al. 2012; Dababnah and Parish 2016a, 2016b; Ferraioli and Harris 2013; Kuravackel et al. 2018; Mazzucchelli et al. 2018; Radley et al. 2014) or partially (Dykens et al. 2014; Karst et al. 2015; Matthews et al. 2018; Roberts et al. 2011; Schultz et al. 2012). One study also limited itself to evaluating only the process of implementing the procedure practiced by the parents rather than evaluating the implementation fidelity of the programs’ facilitators (Matthews et al. 2018). This was analyzed by assessing the evolution over time and not by calculating the average of the data used to evaluate the process. The evaluation of parent’s implementation fidelity of a program is an important measure, as an increase in parents’ adherence to the program can have long-term effects on the parent (Oono et al. 2013; Strauss et al. 2012).

Dababnah and Parish (2016a, 2016b) were the only ones to adapt their program during implementation (the facilitators chose to change the focus of certain domains of the program depending on the participants’ needs). Ferraioli and Harris (2013) also suggested ways to adapt their program for future implementation. Effectively, Durlak and DuPre (2008) and Durlak (2010) highlight the importance of reporting any changes made to the initial program during implementation. For Webster-Stratton (2007, cited by Dababnah and Parish 2016a), being able to adapt the content of a program to correspond to the needs of different groups is a necessary element for implementation fidelity. Finally, Ferraioli and Harris (2013) was the only study to mention a source of potential bias due to implementation fidelity data being collected by the first author.

Eight of the twelve studies were interested in assessing the social validity of the program, either through questionnaires (Kuravackel et al. 2018; Matthews et al. 2018; Mazzucchelli et al. 2018; Radley et al. 2014), open-ended questions (Benn et al. 2012; Dababnah and Parish 2016a, 2016b), or a combination of these two methods (Schultz et al. 2012).

Methodological Quality and Levels of Evidence

The methodological scores and levels of evidence are included in Table 1.

The percentage of adherence to the STROBE guidelines varied between 84% (Benn et al. 2012) and 100% (Karst et al. 2015; Matthews et al. 2018).

The level of evidence determined among the NHMRC guidelines varied between II (Benn et al. 2012; Karst et al. 2015; Kuravackel et al. 2018; Roberts et al. 2011) and III-1 (Schultz et al. 2012) for five RCT studies and between III-1 and IV for the studies using other research designs.

Risk of Bias in Individual Studies

The risk of bias assessment of RCT studies is included in Table 3.

It was considered that Schultz et al. (2012) used a RCT research methodology even though the authors reported that their research methodology was only quasi-experimental because parents were assigned based on chosen time slots as opposed to a completely randomized control trial. Consequently, the study by Schultz et al. (2012) was the only study out of the five considered to have a high selection risk of bias.

Discussion

This systematic review provides preliminary evidence about the effects of group training programs for parents of children with ASD on their stress levels and/or quality of life. The scope of the results is limited by a low number of participants, sociodemographic heterogeneity, various research methods, an elevated risk of bias of RCTs, a variety of tools used to measure parental stress and quality of life, as well as important variations among programs with regard to the manner in which they evaluated program implementation fidelity.

Programs of the included studies showed overall good implementation fidelity. Nevertheless, it should be noted that none of them assessed all of the areas advocated by Durlak and DuPre (2008) and Durlak (2010). Indeed, these authors suggest five main areas that should be documented in implementation studies: (1) fidelity, the extent to which the program implemented adheres to the original program; (2) dosage, which refers to how much of the original program has actually been delivered; (3) quality, which refers to how well the different components have actually been delivered (clearly and correctly); (4) participant responsiveness, which evaluates if the program stimulates participants’ interest and holds their attention; and (5) program differentiation, the extent to which a program can be distinguished from other existing programs (program’s uniqueness). They also name three additional areas: (6) monitoring control groups, which involves describing the nature and quantity of services received by members of these groups (treatment contamination, usual care, alternative services); (7) program reach (e.g., participation rates, program scope), which refers to the rate of involvement and representativeness of program participants; and (8) program adaptations that refer to changes made in the original program during implementation (program modification, reinvention).

Among the studies included in this review, the Parenting Stress Index (PSI) is the most used tool for evaluating stress levels. Correspondingly, parental stress levels are mainly evaluated with this instrument within the ASD literature (Hayes and Watson 2013). It consists of a self-report questionnaire completed by a parent that enables them to measure their level of stress in two domains for the long form: the child domain (which references the stress caused by taking care of child and the child’s characteristics that make educating them more difficult) and the parental domain (which refers to the stress derived directly from parental characteristics and functioning). The short form consists of the following three subscales: Parental Distress, Parent-Child Dysfunctional Interaction, and Difficult Child (Hayes and Watson 2013). Recently, authors have criticized the use of these self-reports by questioning their pertinence in relation to physiological measures. Factor et al. (2018) assessed the stress levels of 27 mothers of children with ASD using the Perceived Stress Reactivity Scale (PSRS) and a measurement of their heart rate variability during interaction tasks. The authors observed that the two measures were not significantly correlated, suggesting that they could reflect different components in participants’ stress experiences. Interestingly, these results could be linked with the work of Nabi et al. (2013) in their large cohort study. These researchers found that people with the same perceived stress level presented different physiological reactions to stress. In fact, participants who thought stress could affect their health had an increased risk of coronary heart disease, regardless of their perceived stress level, compared to participants who did not report that stress could affect their health.

Only two included studies evaluated parental quality of life of parents. Even though quality of life is a main concern of health organizations (Soulas and Brédart 2012), it is considered as the gold standard in terms of evaluating health interventions (Jonsson et al. 2017). This concept not only allows us to operationalize the well-being of individuals in an attempt to improve it but also serves as a common language to allow stakeholders to collaborate on making positive changes (Schalock 2004, cited by Chiang and Wineman 2014). Within the literature concerning the quality of life of parents with children with ASD (Eapen and Guan 2016; Vasilopoulou and Nisbet 2016), the primary measures are the WHOQOL-BREF (the World Health Organization Quality of Life Assessment) and the SF-36 or SF-12 (Short Form Health Survey version). Nevertheless, Eapen and Guan (2016) suggest using specific measures to evaluate the quality of life of families of a child with ASD, such as Quality of Life Measure for Parents of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder, a measure developed by Eapen et al. (2014) (cited by Eapen and Guan 2016). Other authors (e.g., Cappe et al. 2011; Cappe, Poirier, Sankey, Belzil, & Dionne 2017) have also created a specific tool.

Among the twelve studies included in this review, four did not observe a significant effect from the intervention on the parents’ stress level, two of which were RCTs. In their review, Bonis (2016) emphasizes that although parent training programs have been shown to be effective on certain outcomes, parents continue to report high levels of stress. These results also agree with the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE 2013) and the review by Oono et al. (2013) that only consider RCTs. They concluded a lack of statistical evidence concerning the improvement of parental stress following intervention. Among the eight studies included in this review that showed a significant effect of their program on the parents’ stress level, six proposed mindfulness training to parents. This approach consists of paying attention to an experience in a particular way: consciously, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally (Kabat-Zinn 1994). It is at the core of the so-called “third wave” interventions among cognitive and behavioral therapies (Heeren 2011). Mindfulness training is compatible with parents who are confronted to certain difficulties, such as a child with a disability or a chronic illness (Blackledge and Hayes 2006; Minor et al. 2006, cited by Deplus 2011). For example, a mindfulness intervention involving mothers of children on the autism spectrum perceived a decreased level of stress and an increase in their feeling of parental sense of competence (Singh et al. 2004, 2006, 2007, as cited by Deplus 2011). In addition, these same authors indicated that changes are observed among the children, especially concerning a decrease of aggressive behaviors and an improvement of social skills. The mothers learned another way to relate to events and not a series of specific skills aimed at changing their child’s behavior (Singh et al. 2006, cited by Deplus 2011). It seems that teaching parents educational skills in direct connection with their children is not necessarily a requirement for lowering their stress levels.

To obtain the benefits of these mindfulness-training programs, it is essential to practice outside of sessions (Biegel et al. 2009, cited by Deplus 2011). Parents who stopped practicing at the end of the program could be the reason why observed improvements in parental stress at posttest were not observed at the follow-up of the two included studies proposing mindfulness exercises (Dykens et al. 2014; Ferraioli and Harris 2013).

Results of this review are supported by two recent literature reviews that were specifically interested in the effects of programs created for parents of children with ASD on parental outcomes [see Catalano et al. 2018 for a systematic review and Da Paz and Wallander 2017 for a narrative review]. Thus, Catalano et al. (2018) identified different themes and subthemes as being central components for improving parental well-being, such as training in stress management strategies (e.g., mindfulness) or acceptance. Da Paz and Wallander (2017) concluded that the most promising interventions for improving parents’ mental health seem to be part of the third wave of cognitive and behavioral therapies (notably, relaxation techniques, stress management, reducing stress based on mindfulness, and acceptance and commitment therapy). Similarly, many researchers have shown promising effects in acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) for helping parents to adapt better to the difficulties associated with the education of their child on the autism spectrum (Blackledge and Hayes 2006; Gould et al. 2018; Poddar et al. 2017). ACT is a recent implementation from the behavioral science research that corresponds to this third wave, of which mindfulness training is one of the components. In ACT, the presence of a difficult psychological event does not define a disorder, but rather a persistence in trying to escape it unsuccessfully. Therefore, the reduction of stress is not the primary goal, instead the therapy seeks to significantly increase people’s behaviors that are in line with their values (Monestès and Villatte 2011). Parents of children with ASD are susceptible to continue experiencing elevated stress levels, this stress can affect their ability to engage in behaviors based on personal values, which are most likely to be a source of well-being.

Recommendations for Future Research

Future experimental studies on the effectiveness of parent training programs in the field of autism should focus on parents’ quality of life measures. More research is needed to determine the validity of stress measures for parents of children with ASD and develop tools to measure quality of life more specific to families of children with ASD. Researchers should also be alert to measure the multiple aspects of their intervention’s implementation as recommended by Durlak and DuPre (2008) and Durlak (2010). Finally, emerging evidence suggests mindfulness training is a promising tool for improving the well-being among parents of children with ASD. Further investigation is needed to explore the positive effects of other methods proposed by the third wave of cognitive and behavioral therapies, such as ACT.

Limitations

This systematic review has methodological limitations; notably, the included articles are only in English or French. The fact that two studies in this review do not exclusively include parents of children with ASD could also be considered a limitation. The included studies did not use the same procedure to confirm ASD diagnosis. Finally, the small number of articles included and the fact that they were only scattered across 2 countries (the USA and Australia) limit the generalizability of findings to the target population.

References

Alain, M., & Dessureault, D. (2009). Elaborer et évaluer les programmes d’intervention psychosociale. Québec: Presses de l’Université du Québec.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Barroso, N. E., Mendez, L., Graziano, P. A., & Bagner, D. M. (2017). Parenting stress through the lens of different clinical groups: a systematic review & meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(3), 449–461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0313-6.

Bearss, K., Burrell, T. L., Stewart, L. M., & Scahill, L. (2015a). Parent training in autism spectrum disorder: what’s in a name? Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 18(2), 170–182. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-015-0179-5.

Bearss, K., Johnson, C., Smith, T., Lecavalier, L., Swiezy, N., Aman, M., et al. (2015b). Effect of parent training vs parent education on behavioral problems in children with autism spectrum disorder. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA, 313(15), 1524–1533. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.3150.

Beaudoin, A. J., Sébire, G., & Couture, M. (2014). Parent training interventions for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Autism Research and Treatment. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/839890.

Benn, R., Akiva, T., Arel, S., & Roeser, R. W. (2012). Mindfulness training effects for parents and educators of children with special needs. Developmental Psychology, 48, 1476–1487. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027537.

Black, M. E., & Therrien, W. J. (2018). Parent training programs for school-age children with autism: a systematic review. Remedial and Special Education, 39(4), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932517730645.

Blackledge, J. T., & Hayes, S. (2006). Using acceptance and commitment training in the support of parents of children diagnosed with autism. Child and Family Behavior Therapy, 28(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1300/J019v28n01_01.

Bonis, S. (2016). Stress and parents of children with autism: a review of literature. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(3), 153–163. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2015.1116030.

Bradshaw, J., Koegel, L. K., & Koegel, R. L. (2017). Improving functional language and social motivation with a parent-mediated intervention for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(8), 2443–2458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3155-8.

Bradshaw, J., Bearss, K., McCracken, C., Smith, T., Johnson, C., Lecavalier, L., et al. (2018). Parent education for young children with autism and disruptive behavior: response to active control treatment. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 0(0), 1–11,. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2017.1381913.

Brookman-Frazee, L., Stahmer, A., Baker-Ericzen, N. J., & Tsai, K. (2006). Parenting interventions for children with autism spectrum and disruptive behavior disorders: opportunities for cross-fertilization. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 9(3–4), 181–200. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-006-0010-4.

Cappe, E., Wolff, M., Bobet, R., & Adrien, J.-L. (2011). Quality of life: a key variable to consider in the evaluation of adjustment in parents of children with autism spectrum disorders and in the development of relevant support and assistance programmes. Quality of Life Research, 20(8), 1279–1294. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-011-9861-3.

Cappe, E., Poirier, N., Sankey, C., Belzil, A. & Dionne, C. (2017). Quality of life of french canadian parents raising a child with autism spectrum disorder and effects of psychosocial factors. Quality of Life Research, 27(4), 955–967. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-017-1757-4.

Catalano, D., Holloway, L., & Mpofu, E. (2018). Mental health interventions for parent carers of children with autistic spectrum disorder: practice guidelines from a critical interpretive synthesis (CIS) systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(2), 341. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15020341.

Chiang, H. M., & Wineman, I. (2014). Factors associated with quality of life in individuals with autism spectrum disorders: a review of literature. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8, 974–986. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2014.05.003.

Clément, C., & Schaeffer, E. (2010). Evaluation de la validité sociale des interventions menées auprès des enfants et adolescents avec un TED. Revue de Psychoéducation, 39(2), 207–218.

Clifford, T., & Minnes, P. (2013). Who participates in support groups for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders? The role of beliefs and coping style. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43(1), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1561-5.

Da Paz, N. S., & Wallander, J. L. (2017). Interventions that target improvements in mental health for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: a narrative review. Clinical Psychology Review, 51, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.10.006.

Dababnah, S., & Parish, S. L. (2016a). Feasibility of an empirically based program for parents of preschoolers with autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 20(1), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314568900.

Dababnah, S., & Parish, S. L. (2016b). Incredible years program tailored to parents of preschoolers with autism: pilot results. Research on Social Work Practice, 26(4), 372–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731514558004.

Deplus, S. (2011). Les interventions psychologiques basées sur la pleine conscience pour l’enfant, l’adolescent et leurs parents. In I. Kotsou & A. Heeren (Eds.), Pleine Conscience et Acceptation (pp. 61–81). Bruxelles: De Boeck.

Derguy, C., Michel, G., M’Bailara, K., Roux, S., & Bouvard, M. (2015). Assessing needs in parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: a crucial preliminary step to target relevant issues for support programs. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 40(2), 156–166. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2015.1023707.

Derguy, C., Poumeyreau, M., Pingault, S., & M’Bailara, K. (2018). Un programme d’éducation thérapeutique destiné à des parents d’enfant avec un TSA: résultats préliminaires concernant l’efficacité du programme ETAP. L’Encéphale. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2017.07.004.

Durlak, J. A. (2010). The importance of doing well in whatever you do: a commentary on the special section, “implementation research in early childhood education”. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 25, 348–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2010.03.003.

Durlak, J. A., & DuPre, E. P. (2008). Implementation matters: a review of research on the influence of implementation on program outcomes and the factors affecting implementation. American Journal of Community Psychology, 41(3–4), 327–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-008-9165-0.

Dykens, E. M., Fisher, M. H., Taylor, J. L., Lambert, W., & Miodrag, N. (2014). Reducing distress in mothers of children with autism and other disabilities: a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 134(2), e454–e453. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-3164.

Eapen, V., & Guan, J. (2016). Parental quality of life in autism spectrum disorder: current status and future directions. Acta Psychopathologica, 2(5). https://doi.org/10.4172/2469-6676.100031.

Factor, R. S., Swain, D. M., & Scarpa, A. (2018). Child autism spectrum disorder traits and parenting stress: the utility of using a physiological measure of parental stress. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48, 1081–1091. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3397-5.

Ferraioli, S. J., & Harris, S. L. (2013). Comparative effects of mindfulness and skills-based parent training programs for parents of children with autism: feasibility and preliminary outcome data. Mindfulness, 4, 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0099-0.

Goldman, S. E., Glover, C. A., Lloyd, B. P., Barton, E. E., & Mello, M. P. (2017). Effects of parent implemented visual schedule routines for african american children with ASD in low-income home settings. Exceptionality, 26(3), 162–175.

Gould, E. R., Tarbox, J., & Coyne, L. (2018). Evaluating the effects of acceptance and commitment training on the overt behavior of parents of children with autism. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 7, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.06.003.

Goussot, T., Auxiette, C., & Chambres, P. (2012). Réussir la prise en charge des parents d’enfants autistes pour réussir la prise en charge de leur enfant. Annales Médico Psychologiques, 170, 456–460. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2010.11.021.

Harrop, C. (2015). Evidence-based, parent-mediated interventions for young children with autism spectrum disorder: the case of restricted and repetitive behaviors. Autism, 19(6), 662–672. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314545685.

Hayes, S. A., & Watson, S. L. (2013). The impact of parenting stress: a meta-analysis of studies comparing the experience of parenting stress in parents of children with and without autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 43, 629–642. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-012-1604-y.

Heeren, A. (2011). Processus psychologiques et pleine conscience: au cœur de la troisième vague. In I. Kotsou & A. Heeren (Eds.), Pleine conscience et acceptation (pp. 61–81). Bruxelles: De Boeck.

Hock, R., Yingling, M. E., & Kinsman, A. (2015). A parent-informed framework of treatment engagement in group-based interventions. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 3372–3382. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0139-1.

Hong, E. r., Neely, L., Gerow, S., & Gann, C. (2018). The effect of caregiver-delivered social-communication interventions on skill generalization and maintenance in ASD. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 74, 57–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2018.01.006.

Hsiao, Y. J., Higgins, K., Pierce, T., & Whitby, S. (2017). Parental stress, family quality of life, and family-teacher partnerships: families of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 70, 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.08.01.

Iadarola, S., Levato, L., Harrison, B., Smith, T., Lecavalier, L., Johnson, C., et al. (2018). Teaching parents behavioral strategies for autism spectrum disorder (ASD): effects on stress, strain, and competence. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1031–1040. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3339-2.

Ibanez, L. V., Kobak, K., Swanson, A., Wallace, L., Warren, Z., & Stone, W. L. (2018). Enhancing interactions during daily routines: a randomized controlled trial of a web-based tutorial for parents of young children with ASD. Autism Research, 11(4), 667–678. https://doi.org/10.1002/aur.1919.

Ilg, J., Jebrane, A., Dutray, B., Wolgensinger, L., Rousseau, M., & Paquet, A. (2017). Évaluation d’un programme francophone de formation aux habiletés parentales dans le cadre des troubles du spectre de l’autisme auprès d’un groupe pilote. Annales Médico-psychologiques, revue psychiatrique, 175(5), 430–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amp.2016.01.018.

Ilg, J., Jebrane, A., Paquet, A., Rousseau, M., Dutray, B., Wolgensinger, et al. (2018). Evaluation of a french parent-training program in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Psychologie Française, 63(2), 181–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psfr.2016.12.004.

Ingersoll, B., Wainer, A. L., Berger, N. I., Pickard, K. E., & Bonter, N. (2016). Comparison of a self-directed and therapist-assisted telehealth parent-mediated intervention for children with ASD: a pilot RCT. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 46(7), 2275–2284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2755-z.

Jonsson, U., Alaie, I., Wilteus, A. L., Zander, E., Marschik, P. B., Coghill, et al. (2017). Annual research review: quality of life and childhood mental and behavioral disorders—a critical review of the research. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(4), 439–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12645.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: mindfulness meditation in everyday life. New York: Hyperion.

Kaminski, J. W., Valle, L. A., Filene, J. H., & Boyle, C. L. (2008). A Meta-Analytic Review of Components Associated with Parent Training Program Effectiveness. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(4), 567–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-007-9201-9.

Karst, J. S., Van Hecke, A. M., Carson, A. M., Stevens, S., Schohl, K., & Dolan, B. (2015). Parent and family outcomes of PEERS: a social skills intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45, 752–765. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2231-6.

Kasari, C., Gulsrud, A., Paparella, T., Hellemann, G., & Berry, K. (2015). Randomized comparative efficacy study of parent-mediated interventions for toddlers with autism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 83(3), 554–563. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039080.

Klinger, L. G., Ence, W., & Meyer, A. (2013). Caregiver-mediated approaches to managing challenging behaviors in children with autism spectrum disorder. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 15(2), 225–233.

Kuravackel, G. M., Ruble, L. A., Reese, R. J., Ables, A. P., Rodgers, A. D., & Toland, M. D. (2018). COMPASS for hope: evaluating the effectiveness of a parent training and support program for children with ASD. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(2), 404–416. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3333-8.

Leadbitter, K., Aldred, C., McConachie, H., Le Couteur, A., Kapadia, D., Charman, T., et al. (2018). The autism family experience questionnaire (AFEQ): an ecologically-valid, parent-nominated measure of family experience, quality of life and prioritised outcomes for early intervention. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1052–1062. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3350-7.

Lecavalier, L., Pan, X., & Smith, T. (2018). Parent stress in a randomized clinical trial of atomoxetine and parent training for children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 980–987. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3345-4.

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., & Ioannidis, J. P. A. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700.

Lovell, B., Moss, M., & Wetherell, M. A. (2012). With a little help from my friends: psychological, endocrine and health corollaries of social support in parental caregivers of children with autism or ADHD. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33, 682–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.11.014.

MacCormack, J. W. H. (2017). What youths with autism spectrum disorder and their parents want from social competence programs. Exceptionality Education International, 27, 116–146.

Matthews, J. M., & Hudson, A. M. (2001). Guidelines for evaluating parent training programs. Family Relations, 50, 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2001.00077.x.

Matthews, N. L., Orr, B. C., Harris, B., McIntosh, R., Openden, D., & Smith, C. J. (2018). Parent and child outcomes of jumpstart, an education and training program for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 56, 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2018.08.009.

Mazurek, M. O. (2014). Loneliness, friendship, and well-being in adults with autism spectrum disorders. Autism, 18(3), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361312474121.

Mazzucchelli, T. G., Jenkins, M., & Sofronoff, K. (2018). Building bridges triple P: pilot study of a behavioral family intervention for adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 76, 46–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2018.02.018.

McConachie, H., & Diggle, T. (2007). Parent implemented early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 13, 120–129.

Monestès, J. L., & Villatte, M. (2011). La thérapie d’acceptation et d’engagement ACT. Issy-les-Moulineaux: Elsevier Masson.

Munder, T., & Barth, J. (2017). Cochrane’s risk of bias tool in the context of psychotherapy outcome research. Psychotherapy Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1411628.

Nabi, H., Kivimäki, M., Batty, G. D., Shipley, M. J., Britton, A., Brunner, E. J., et al. (2013). Increased risk of coronary heart disease among individuals reporting adverse impact of stress on their health: the Whitehall II prospective cohort study. European Heart Journal, 34(34), 2697–2705. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/eht216.

National Health Medical Research Council. (1999). A guide to the development, implementation and evaluation of clinical practice guidelines. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). (2013). Autism: the management and support of children and young people on the autism spectrum. London: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

O’Nions, E., Happé, F., Evers, K., Boonen, H., & Noens, I. (2018). How do parents manage irritability, challenging behavior, non-compliance and anxiety in children with autism spectrum disorders? A meta-synthesis. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1272–1286. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3361-4.

Oono, I. P., Honey, E. J., & McConachie, H. (2013). Parent-mediated early intervention for young children with autism spectrum disorders (ASD). Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 4(CD009774). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009774.pub2.

Parsons, D., Cordier, R., Vaz, S., & Lee, H. C. (2017). Parent-mediated intervention training delivered remotely for children with autism spectrum disorder living outside of urban areas: systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(8), e198. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.6651.

Pastor-Cerezuela, G., Fernandez-Andres, M. I., Tarraga-Minguez, R., Navarro-Pena, J. M., et al. (2016). Parental stress and ASD: relationship with autism symptom severity, IQ, and resilience. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 31(4), 300–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357615583471.

Patterson, S. Y., Smith, V., & Mirenda, P. (2012). A systematic review of training programs for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders: single subject contributions. Autism, 16(5), 498–522. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361311413398.

Pfeiffer, B., Piller, A., Giazzoni-Fialko, T., & Chainani, A. (2016). Meaningful outcomes for enhancing quality of life for individuals with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 42(1), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250.2016.1197893.

Pickles, A., Le Couteur, A., Leadbitter, K., Salomone, E., Cole-Fletcher, R., Tobin, H., et al. (2016). Parent-mediated social communication therapy for young children with autism (PACT): long-term follow-up of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 388, 2501–2509. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31229-6.

Poddar, S., Sinha, V. K., & Mukherjee, U. (2017). Impact of acceptance and commitment therapy on valuing behavior of parents of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. Psychology and Behavioral Science, 3(3). https://doi.org/10.19080/PBSIJ.2017.03.555614.

Poslawsky, I. E., Naber, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., van Daalen, E., van Engeland, H., van Jzendoorn, I., et al. (2015). Video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting adapted to autism (VIPP-AUTI): a randomized controlled trial. Autism, 19(5), 588–603. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361314537124.

Postorino, V., Sharp, W. G., McCracken, C. E., Bearss, K., Burrell, T. L., et al. (2017). A systematic review and meta-analysis of parent training for disruptive behavior in children with autism spectrum disorder. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20(4), 391–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-017-0237-2.

Preece, D., & Trajkovski, V. (2017). Parent education in autism spectrum disorder- a review of the literature. Hrvatska revija za rehabilitacijska istraživanja, 53(1), 128–138. https://doi.org/10.31299/hrri.53.1.10.

Radley, K. C., Jenson, W. R., Clark, E., & O’Neill, R. E. (2014). The feasibility and effects of a parent-facilitated social skills training program on social engagement of children with autism spectrum disorders. Psychology in the Schools, 51(3), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21749.

Reed, P., Osborne, L. A., Makrygianni, M., Waddington, E., Etherington, A., & Gainsborough, J. (2013). Evaluation of the barnet early autism model (BEAM) teaching intervention programme in a ‘real world’ setting. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 7(6), 631–638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2013.02.009.

Roberts, J., Williams, K., Carter, M., Evans, D., Parmenter, T., Silove, N., Clark, T., Warren, A., et al. (2011). A randomised controlled trial of two early intervention programs for young children with autism: centre-based with parent program and home-based. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5, 1553–1566. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.03.001.

Robertson, S. M. (2010). Neurodiversity, quality of life, and autistic adults: shifting research and professional focuses onto real-life challenges. Disability Studies Quarterly, 30(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.18061/dsq.v30i1.1069.

Samadi, S. A., McConkey, R., & Kelly, G. (2012). Enhancing parental well-being and coping through a family-centred short course for Iranian parents of children with an autism spectrum disorder. Autism, 17(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361311435156.

Schultz, T. R., Schmidt, C. T., & Stichter, J. P. (2011). A review of parent education programs for parents of children with autism spectrum disorders. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 26(2), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088357610397346.

Schultz, T. R., Stichter, J. P., Herzog, M. J., McGhee, S. D., & Lierheimer, K. (2012). Social competence intervention for parents (SCI-P): comparing outcomes for a parent education program targeting adolescents with ASD. Autism Research and Treatment. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/681465.

Shepherd, D., Csako, R., Landon, J., Goedeke, S., & Ty, K. (2018). Documenting and understanding parent’s intervention choices for their child with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 988–1001. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3395-7.

Siller, M., Morgan, L., Turner-Brown, L., Baggett, K. M., Baranek, G. T., Brian, J., et al. (2013). Designing studies to evaluate parent-mediated interventions for toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Early Intervention, 35(4), 355–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815114542507.

Soulas, T., & Brédart, A. (2012). Qualité de vie et santé. In S. Sultan & I. Varescon (Eds.), Psychologie de la Santé (pp. 17–40). Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Strauss, K., Vicari, S., Valeri, G., D’Elia, L., Arima, S. & Fava, F. (2012). Parent inclusion in Early Intensive Behavioral Intervention: The influence of parental stress, parent treatment fidelity and parent-mediated generalization of behavior targets on child outcomes. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33, 688–703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.11.008.

Strauss, K., Mancini, F., & Fava, L. (2013). Parent inclusion in early intensive behavior interventions for young children with ASD: a synthesis of meta-analyses from 2009 to 2011. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 34(9), 2967–2985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2013.06.007.

Tellegen, C. L., & Sanders, M. R. (2014). A randomized controlled trial evaluating a brief parenting program with children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 82(6), 1193–1200. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037246.

Vasilopoulou, E., & Nisbet, J. (2016). The quality of life of parents of children with autism spectrum disorder: a systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 23, 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2015.11.008.

von Elm, E., Altman, D. G., Egger, M., Pocock, S. J., Gotzsche, P. C., & Vandenbroucke, J. P. (2007). The strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 61(4), 344–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008 Lancet, 370, 1453-1457.

Wainer, A. L., Hepburn, S., & McMahon Griffith, E. (2017). Remembering parents in parent-mediated early intervention: an approach to examining impact on parents and families. Autism, 21(1), 5–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361315622411.

Wheeler, J. J., Carter, S. L., Mayton, M. R. & Thomas, R. A. (2002). Structural analysis of instructional variables and their effects on task-engagement and selfaggression. Education and Training in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 37(4), 391–398.

Funding

This study has received funding from the Caisse Nationale de Solidarité pour l’Autonomie (CNSA) through the call for the project “Autism 2014” proposed by the Institut de Recherche En Santé Publique (IRESP).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lichtlé, J., Downes, N., Engelberg, A. et al. The Effects of Parent Training Programs on the Quality of Life and Stress Levels of Parents Raising a Child with Autism Spectrum Disorder: a Systematic Review of the Literature. Rev J Autism Dev Disord 7, 242–262 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00190-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00190-x