Abstract

Background

Large epidemiological databases facilitate the study of medical care in different subgroups of the population and how such care compares with standard treatment guidelines. This study aimed for such analyses regarding utilization of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) for epilepsy in Germany.

Method

The data source was the Disease Analyzer® database that is representative for the German population and assembles anonymous demographic and medical (diagnoses, prescriptions) data obtained from the practice computer system of general practitioners and specialists throughout Germany. A total of 43,712 adult patients with an epilepsy diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition [ICD10] code: G40.X) seen in 2010–2012 by 346 neurologists were retrospectively analysed according to sociodemographic characteristics, comorbidity, and AED treatment. Multivariate logistic regression was applied to calculate adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs).

Results

As compared with women, men were less likely to receive lamotrigine (OR 0.68; 95 % CI 0.65–0.72; p < 0.001) and were treated preferably with carbamazepine (OR 1.29; 95 % CI 1.23–1.35; p < 0.001). As compared with patients covered by private health insurance (PHI), patients with statutory health insurance (SHI) were treated more often with valproate (OR 1.19; 95 % CI 1.07–1.31; p < 0.001) and showed a higher rate of obesity (SHI: 3.1 %; PHI: 1.6 %; p < 0.001), while PHI was associated with administration of levetiracetam (OR 1.27; 95 % CI 1.16–1.4; p < 0.001). Carbamazepine (OR 1.25; 95 % CI 1.17–1.31; p < 0.001) and primidone (OR 1.23; 95 % CI 1.08–1.38; p < 0.001) were administered to a larger extent in rural versus urban areas. Lamotrigine (OR 1.31; 95 % CI 1.23–1.39; p < 0.001) was used more often in West than in East Germany. Living in an urban community raised the likelihood of being treated with levetiracetam (OR 1.23; 95 % CI 1.17–1.28; p < 0.001).

Conclusions

In spite of common guidelines, AED treatment differed significantly among adults with epilepsy in Germany. Besides gender, type of health insurance and place of residence strongly influenced AED administration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In spite of common guidelines, antiepileptic drug (AED) treatment differed significantly among adults with epilepsy in Germany. |

The majority of patients received one of four AEDs, including valproate, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine. |

Gender, type of health insurance (private vs. statutory health insurance), and place of residence (urban vs. rural community, East vs. West Germany) strongly influenced AED administration. |

1 Introduction

A nationwide evaluation in Germany revealed a 2009 period prevalence of patients with epilepsy taking antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) of 9.1 per 1,000 [1]. More than 83 % of the patients were treated with one of four AEDs, including valproate, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine. A trend was noted towards increased administration of new AEDs and generic formulations [2]. This is in line with German guidelines (www.dgn.org/leitlinien-online-2012), which favor new AEDs, especially lamotrigine and levetiracetam, and discourage the use of old AEDs, such as carbamazepine or phenytoin, because of potential pharmacokinetic interactions and concerns regarding poor tolerability. However, these studies also provided doubts over whether, despite common guidelines, antiepileptic treatment is provided equally to all subgroups of the German population as, for example, elderly patients still frequently received phenytoin and primidone [1].

By analysing a large representative database of German prescriptions, the aim of the current study was to evaluate characteristics of anticonvulsant treatment in different subgroups of German adult patients with epilepsy.

2 Methods

2.1 Data Source

The Disease Analyzer® database designed and run by IMS Health GmbH & Co. (Frankfurt, Germany) served as the data source. It assembles drug prescriptions, diagnoses, and basic medical and demographic data obtained from the practice computer system of general practitioners and specialists throughout Germany. The sampling method of private practices for the Disease Analyzer® database is based on summary statistics of all physicians in private practice in Germany published yearly by the German Medical Association (Bundesaerztekammer; http://www.baek.de). The panel is designed according to the following strata: specialist group, German federal state, community size category, and age of physician. The database records physician specialty, region of office (West or East Germany), and the following patient data: age, gender, place of residence, insurance status (private or statutory health insurance [SHI]), diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 10th edition [ICD10]), date of visit, and medication, prescribed down to package level. The database does not designate any personal data but exclusively anonymous information (in accordance with § 3 Abs. 6 “Bundesdatenschutzgesetz”—German Federal Data Protection Act). The Disease Analyzer® database was found to be representative and valid for the German population with respect to epidemiological and pharmacoeconomic characteristics [3].

2.2 Patients and Antiepileptic Drugs

The data from 346 neurological private practices throughout Germany, with approximately 1.8 million patients seen in the time period 2010–2012, formed the basis of the study. In Germany, patients usually and predominantly receive prescriptions from physicians in private practices. A minority of prescriptions is issued by a subset of hospitals with outpatient clinics, which were not part of the database used in this study. We included all adults (≥18 years) with the assured diagnosis ‘epilepsy’ (ICD10: G40.X: Epilepsy) documented by the treating neurologist between 1 January 2010 and 31 December 2012. The ICD10 code G40.X includes ‘localization-related epilepsy’ (G40.0, G40.1, G40.2), ‘generalized epilepsy’ (G40.3, G40.4), ‘special epileptic syndrome’ (G40.5), unspecified ‘grand mal seizures’ (G40.6), unspecified ‘petit mal seizures’ (G40.7), and other or unspecified epilepsy (G40.8, G40.9).

Recorded sociodemographic variables of each patient comprised gender, place of residence, and health insurance status. In addition, the following comorbidities were recorded, which may be associated with the epilepsy syndrome, influence the choice of AEDs, or occur as treatment-emergent side effects: mental retardation (F70–79); depression (F32–F33); alcohol abuse (F10); dissociative disorder (F44), including psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES); headache (G43–G44); and obesity (E66–E68).

The prescriptions of all drugs that were licensed or prescribed for the treatment of epilepsy in Germany were included. The vast majority were drugs listed under the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) code N03 ‘antiepileptics’. Every AED with the ATC code N03 was considered when it was marketed in Germany in 2010–2012, such as carbamazepine, clonazepam, eslicarbazepine, ethosuximide, felbamate, gabapentin, lacosamide, lamotrigine, levetiracetam, mesuximide, oxcarbazepine, phenobarbital, phenytoin, pregabalin, primidone, rufinamide, stiripentol, sulthiame, tiagabine, topiramate, valproate, vigabatrin, and zonisamide. In addition, the benzodiazepines clobazam, diazepam, and lorazepam, which are listed under the ATC code N05, were included because they are frequently prescribed in Germany as rescue medication for seizure clusters or status epilepticus. Bromide was also considered because it is licensed in Germany for generalized tonic-clonic seizures in childhood epilepsy. Each AED was further classified as an ‘old’ or ‘new’ AED, and all marketed AED were divided into ‘original’ and ‘generic’ brands. This was done to study the effects of evidence regarding probable advantages but higher costs of ‘new’ compared with ‘old’ AEDs [4] and to reflect reimbursement rules of statutory health insurers preferring more cost-efficient ‘generic’ AEDs over higher-priced ‘branded’ AEDs. Old AEDs were defined as drugs that were marketed in Germany before 1980. Market entry after 1980 defined ‘new’ AEDs. Old AEDs were bromide, carbamazepine, clonazepam, diazepam, ethosuximide, lorazepam, mesuximide, phenobarbital, phenytoin, primidone, sulthiame, and valproate. The remainder was classified as ‘new’ AEDs.

Brands that were initially marketed in Germany under patent protection of the specific drug were considered ‘branded’ AEDs. Generic versions of the brand-name drug that were first sold after the loss of patent protection of the specific drug were regarded as ‘generic’ AEDs.

In the presence of common guidelines to treat epilepsy issued by the German Neurological Society (http://www.dgn.org/leitlinien-online-2012), all neurologists in private practice in Germany have the right to prescribe any approved drug to any patient if felt necessary. However, SHI companies in particular may institute regulations of reimbursement favoring one drug or generic compound, which may influence treatment choices.

2.3 Statistics

The total patient group was divided into subgroups according to sociodemographic characteristics. The AED treatment was analysed separately according to gender, health insurance status (SHI vs. private health insurance [PHI]), region (West vs. East Germany), and size of residential community (urban [≥100,000 residents] vs. rural community [<100,000 residents]).

Multivariate logistic regression was applied to calculate odds ratios (ORs) with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) as estimates reflecting the influence of male versus female, SHI versus PHI, size of residential community (urban vs. rural community), and West versus East Germany. The individual ORs were adjusted for all other variables considered. Because of multiple comparisons, findings were considered relevant and are mentioned when the significance level p was below 0.001 and the OR was <0.85 or >1.15. In addition, the chi-squared quadrat test was used to assess group differences. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

3 Results

A total of 43,712 patients were included (Table 1). The majority of patients (79 %) received one of four AEDs, including valproate, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine. However, the utilization of these four AEDs varied significantly between patient subgroups. Patients with PHI were treated to the largest extent with levetiracetam (33 %) compared with patients with SHI, resulting in fewer prescriptions of valproate (25 %) and carbamazepine (15 %) in PHI patients. Carbamazepine was administered most often to East German patients (22 %) among all subgroups considered in this study, and women with epilepsy showed the highest rate of lamotrigine prescription (22 %).

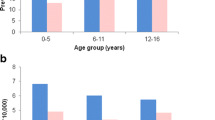

3.1 Gender

Men with epilepsy were more frequently diagnosed with alcohol abuse than were women (female 2.5 %; male 7.1 %; p < 0.001). Women with epilepsy showed a higher rate of depression (female 23.7; male 15.7 %; p < 0.001), headache (female 7.3 %; male 3.5 %; p < 0.001), and dissociative disorders including PNES (women 1.4 %; men 0.9 %; p < 0.001) than men.

Men were treated preferably with carbamazepine (OR 1.29; 95 % CI 1.23–1.35), oxcarbazepine (OR 1.38; 95 % CI 1.27–1.49), or valproate (OR 1.12; 95 % CI 1.07–1.16) (in total: male 60.0 %; female 40.5 %; p < 0.001) as compared with women, while women were more likely to receive lamotrigine than men (female 21.7 %; male 16.7 %; OR 1.47; 95 % CI 1.38–1.53; p < 0.001). As implied by women with epilepsy more frequently complaining of headache, topiramate was more often prescribed to female than male patients (female 5.4 %; male 4.4 %; OR 1.28; 95 % CI 1.17–1.40; p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in administration of levetiracetam (female 26.4 %; male 27.1 %; OR 1.07; 95 % CI 1.02–1.11; p = 0.0035).

3.2 Health Insurance

Patients with epilepsy covered by PHI showed a lower rate of mental retardation than patients with SHI (PHI 2.0 %; SHI 7.4 %; p < 0.001) and were diagnosed less often with alcohol abuse than SHI patients (PHI 3.0 %; SHI 4.9 %; p < 0.001). Obesity was more frequent in patients with SHI than in those with PHI (SHI 3.1 %; PHI 1.6 %; p < 0.001).

There was a marked difference in the use of branded or generic AEDs between both groups, favoring branded AEDs in PHI patients (branded AEDs: PHI 64.4 %; SHI 48.4 %; OR 1.89; 95 % CI 1.73–2.07; p < 0.001; generic AEDs: PHI 63.9 %; SHI 81.7 %; OR 0.41; 95 % CI 0.37–0.45; p < 0.001).

Similarly, in East and West Germany, patients covered with SHI were treated more often with carbamazepine than were patients with PHI (total patient group: PHI 15.0 %; SHI 20.4 %; OR 1.54; 95 % CI 1.35–1.72; p < 0.001), and patients with PHI were associated with more frequent prescriptions of levetiracetam than were patients with SHI (PHI 32.6 %; SHI 26.5 %; OR 1.27; 95 % CI 1.16–1.4; p < 0.001). There was a preponderance of males among patients with PHI (PHI 58.5 %; SHI 49.3 %; p < 0.001) and females in patients with SHI. However, this did not lead to a higher likelihood of administration of valproate in the PHI or lamotrigine in the SHI group. On the contrary, valproate was prescribed to a larger extent to SHI patients (PHI 25.7 %; SHI 29.7 %; OR 1.19; 95 % CI 1.07–1.31; p < 0.001), while both groups were equally treated with lamotrigine (PHI 19.1 %; SHI 19.2 %; OR 1.08; 95 % CI 0.96–1.20; p = 0.21). However, women of child-bearing age (between 18 and 45 years of age) were treated with valproate to a similar extent, irrespective of their health insurance status (women of child-bearing age with SHI 29.8 %; with PHI 29.5 %; p = 0.94).

3.3 West Germany versus East Germany

Patients with epilepsy treated in West Germany were more often diagnosed with depression (West 20.5 %; East 16.9 %; p < 0.001) or dissociative disorders including PNES than patients treated in East Germany (West 1.3 %; East 0.6 %; p < 0.001), while mental retardation (West 6.7 %; East. 9.0 %; p < 0.001) and alcohol abuse (West 4.6 %; East 5.5 %; p < 0.001) was seen more frequently in East than in West German patients.

Lamotrigine was used more often in West than in East Germany (West 20.2 %; East 16.0 %; OR 1.31; 95 % CI 1.23–1.39; p < 0.001). Carbamazepine was used preferably in East as compared with West Germany (West 19.6 %; East 22.0 %; OR 1.14; 95 % CI 1.08–1.20; p < 0.001). West German patients were more likely to receive pregabalin than East German patients (West 4.3 %; East 3.4 %; OR 1.31; 95 % CI 1.16–1.48; p < 0.001) but were treated to a smaller extent with topiramate (West 4.6 %; East 5.9 %; OR 1.31; 95 % CI 1.19–1.44; p < 0.001). However, the most marked difference was seen in the use of benzodiazepines. While benzodiazepines (clobazam, clonazepam, diazepam, or lorazepam) were prescribed to 18.4 % of East German patients, 25.3 % of West German patients were treated with this group of AEDs (p < 0.001). There were no significant differences in the administration of levetiracetam (West 26.9 %; East 26.2 %; OR 1.05; 95 % CI 1.0–1.11; p = 0.06) or valproate (West 29.6 %; East 29.3 %; OR 1.01; 95 % CI 0.96–1.06; p = 0.78).

3.4 Rural versus Urban Communities

In rural areas, patients with epilepsy were more often diagnosed with mental retardation than were patients living in urban communities (urban 5.4 %; rural 7.9 %; p < 0.001). Old AEDs, such as carbamazepine (urban 17.5 %; rural 21.2 %; OR 0.80; 95 % CI 0.76–0.85; p < 0.001) and primidone (urban 2.9 %; rural 3.6 %; OR 0.81; 95 % CI 0.72–0.92; p < 0.001) were infrequently administered in urban areas, while living in an urban community raised the likelihood of being treated with levetiracetam (urban 29.4 %; rural 25.7 %; OR 1.23; 95 % CI 1.17–1.28; p < 0.001).

4 Discussion

This study used a large, epidemiological database to identify and analyse disparities in healthcare provided to adult patients with epilepsy in Germany. All neurologists in private practice in Germany have the right to prescribe any approved drug they feel necessary to any patient. Four AEDs (valproate, levetiracetam, carbamazepine, and lamotrigine) by far dominated German prescriptions for epilepsy, confirming previous findings [1]. As compared with a German study of 2009 [1], the results highlight the general trend to new AEDs in recent years, with proportions of carbamazepine rapidly lowering but valproate showing stable and frequent utilization. Beyond epileptologic evidence and common guidelines, sociodemographic characteristics of patients with epilepsy strongly influenced administration of AEDs. East German males living in rural communities and covered by SHI were still highly likely to receive old AEDs such as carbamazepine or valproate, while new AEDs, such as lamotrigine or levetiracetam were clearly favored in urban West German patients with PHI. This contrasts with the declared political will to provide adequate and equal healthcare to all German residents regardless of their sociodemographic status. The results of this study suggest a possible treatment gap in epilepsy within Germany that is not characterized by people with epilepsy who require but do not receive any treatment [5], but is expressed by the type of treatment that patients receive.

4.1 Health Insurance

The type of health insurance in particular led to marked differences in AED prescriptions, favoring new and branded AEDs in patients with PHI as compared with patients covered by SHI. Strict regulation by SHI companies regarding which drugs or generic compounds are reimbursed may be one reason for this disparity. Patients’ insurance status may be a surrogate for their income level because, in Germany, SHI is compulsory for all employees with an individual monthly income below a certain limit (€4,162.50 in 2010 and €4,237.50 in 2012), who account for more the 80 % of the German working population. Employees with an income above this level and entrepreneurs may opt out and seek PHI. The results suggest that the German healthcare system provides treatment not only according to the needs of patients but also according to their sociodemographic status. Whether this may or may not translate into differing treatment success remains a subject for further studies. However, the frequent use of valproate in patients with SHI, which is accompanied by an increased obesity rate, may fuel this discussion [6].

4.2 Place of Residence

The patient’s place of residence (East or West Germany) influenced the choice of AEDs in addition to whether the patient lived in a rural or urban community. West German patients received pregabalin and especially benzodiazepines to a larger extent than did East German residents, while more East Germans than West were treated with topiramate. The different historical background of East and West German provinces, including medical training, may contribute to these variations.

The different treatment patterns in rural and urban communities confirm previous studies [8]. The reason for this in Germany remains unclear, especially because the current study identified these differences among treating neurologists, excluding other groups of physicians possibly caring for epilepsy patients, such as family physicians. Other studies from Europe [1, 10] and the USA [11] reported a wide range of physicians and specialists involved in epilepsy care and large differences in treatment patterns between specialists and generalists. Living in rural communities was associated with treatment with carbamazepine and primidone, while levetiracetam was preferred in urban areas.

4.3 Patients’ Characteristics

The results support the view that patients’ characteristics, including comorbidities, are considered when prescribing AEDs to individual patients. The different patterns of AED treatment according to the gender of the patient follow common guidelines [12, 13] (www.dgn.org/leitlinien-online-2012), which discourage valproate and recommend lamotrigine in women of child-bearing age with epilepsy. This was followed equally in women with SHI and those with PHI. However, evidence of low teratogenicity of carbamazepine [14] was not associated with preferential administration of this AED in women with epilepsy. As to be expected with the more frequent complaints of headache in women with epilepsy, topiramate, which is approved for prevention of migraine headache in Germany, was prescribed to a larger extent to female than to male patients with epilepsy.

4.4 Strengths and Limitations

The strength of this study was the use of a large, representative database containing physician-based ICD diagnoses along with detailed information on AED prescription. The combination of prescription data and ICD codes for epilepsy was found to be the best model to identify epilepsy cases in managed care organizations [15]. However, diagnostic uncertainty cannot be excluded, particularly regarding the classification of the specific epilepsy syndrome and, hence, the suitability of the AED administered. Moreover, the database did not record detailed characteristics of the patients or the epilepsy syndromes, such as treatment success, adverse reactions, or duration of epilepsy, which may have also influenced treatment choices. In addition, we had only information on prescribed drugs rather than drugs that were actually taken by the patient. Another limitation of the current study is that data on hospital-based patients were missing. In addition, the study lacks a direct measure of socioeconomic status, such as income or years of education, but these data are not readily available in Germany.

5 Conclusions

This retrospective study used a large epidemiological database to analyse administration of AEDs to adults with epilepsy in Germany. In spite of common guidelines, AED treatment differed significantly between subgroups of the population. Besides gender, the type of health insurance and place of residence strongly influenced AED administration. These data may help to better understand treatment disparities in Germany and may guide public health officials to allocate resources according to the needs of different patient groups and the popularity of certain healthcare plans in the population [16]. Prospective studies are needed to assess the extent to which the observed differences are important to patient-related outcomes such as quality of life and seizure freedom.

References

Hamer HM, Dodel R, Strzelczyk A, Balzer-Geldsetzer M, Reese JP, Schoffski O, et al. Prevalence, utilization, and costs of antiepileptic drugs for epilepsy in Germany—a nationwide population-based study in children and adults. J Neurol. 2012;259(11):2376–84.

Strzelczyk A, Haag A, Reese JP, Nickolay T, Oertel WH, Dodel R, et al. Trends in resource utilization and prescription of anticonvulsants for patients with active epilepsy in Germany. Epilepsy Behav. 2013;27(3):433–8.

Becher H, Kostev K, Schroder-Bernhardi D. Validity and representativeness of the “Disease Analyzer” patient database for use in pharmacoepidemiological and pharmacoeconomic studies. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2009;47(10):617–26.

Marson AG, Al-Kharusi AM, Alwaidh M, Appleton R, Baker GA, Chadwick DW, et al. The SANAD study of effectiveness of carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate for treatment of partial epilepsy: an unblinded randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9566):1000–15.

Meyer AC, Dua T, Ma J, Saxena S, Birbeck G. Global disparities in the epilepsy treatment gap: a systematic review. Bul World Health Organ. 2010;88(4):260–6.

Huber J, Mielck A. Morbidity and healthcare differences between insured in the statutory (“GKV”) and private health insurance (“PKV”) in Germany. Review of empirical studies. Bundesgesundheitsblatt Gesundheitsforschung Gesundheitsschutz. 2010;53(9):925–38.

Odeyemi IA, Nixon J. The role and uptake of private health insurance in different health care systems: are there lessons for developing countries? Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:109–18.

Mattsson P, Tomson T, Eriksson O, Brannstrom L, Weitoft GR. Sociodemographic differences in antiepileptic drug prescriptions to adult epilepsy patients. Neurology. 2010;74(4):295–301.

Meyer AC, Dua T, Boscardin WJ, Escarce JJ, Saxena S, Birbeck GL. Critical determinants of the epilepsy treatment gap: a cross-national analysis in resource-limited settings. Epilepsia. 2012;53(12):2178–85.

Malmgren K, Flink R, Guekht AB, Michelucci R, Neville B, Pedersen B, et al. ILAE Commission of European Affairs Subcommission on European Guidelines 1998–2001: the provision of epilepsy care across Europe. Epilepsia. 2003;44(5):727–31.

Begley CE, Basu R, Reynolds T, Lairson DR, Dubinsky S, Newmark M, et al. Sociodemographic disparities in epilepsy care: results from the Houston/New York City health care use and outcomes study. Epilepsia. 2009;50(5):1040–50.

Harden CL, Meador KJ, Pennell PB, Hauser WA, Gronseth GS, French JA, et al. Practice parameter update: management issues for women with epilepsy—focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): teratogenesis and perinatal outcomes: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee and Therapeutics and Technology Assessment Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and American Epilepsy Society. Neurology. 2009;73(2):133–41.

Nunes VD, Sawyer L, Neilson J, Sarri G, Cross JH. Diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults and children: summary of updated NICE guidance. BMJ. 2012;344:e281.

Tomson T, Battino D, Bonizzoni E, Craig J, Lindhout D, Sabers A, et al. Dose-dependent risk of malformations with antiepileptic drugs: an analysis of data from the EURAP epilepsy and pregnancy registry. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(7):609–17.

Holden EW, Grossman E, Nguyen HT, Gunter MJ, Grebosky B, Von Worley A, et al. Developing a computer algorithm to identify epilepsy cases in managed care organizations. Dis Manag. 2005;8(1):1–14.

Schnusenberg O, Loh CP, Nihalani K. The role of financial wellbeing, sociopolitical attitude, self-interest, and lifestyle in one’s attitude toward social health insurance. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2013;11(4):369–81.

Disclosures

The authors report the following possible sources of conflicts of interest.

Dr. Hamer has served on the scientific advisory board of cerbomed, Eisai, Pfizer, and UCB Pharma. He served on the speakers’ bureau of Cyberonics, Desitin, Eisai, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis, and UCB Pharma and received research funding from Desitin, Janssen-Cilag, GlaxoSmithKline, and UCB Pharma.

K. Kostev is an employee of IMS HEALTH, a company that focuses on analysis of pharmacy records and runs the database used in this analysis. However, this study was not part of any business project.

No funding was received for the study or publication of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hamer, H.M., Kostev, K. Sociodemographic Disparities in Administration of Antiepileptic Drugs to Adults with Epilepsy in Germany: A Retrospective, Database Study of Drug Prescriptions. CNS Drugs 28, 753–759 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-014-0187-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40263-014-0187-x