Abstract

Hydatidosis, an important parasitic zoonoses is a major public health as well as economic concern throughout the world. A total of 2100, sheep (2052) and goats (48), slaughtered or spontaneously dead, from various areas of Kashmir valley were screened for the presence of hydatidosis. Out of 2100 cases, 85 were positive for hydatidosis. The frequently infected organs were lungs and liver. The liver was observed to be the most frequently infected organ with relative prevalence of 61.17% followed by lungs (38.82%). The pulmonary cysts were more fertile (55%) compared to hepatic cysts (45%). Histopathologicallly, the cyst wall consisted of the inner germinal, middle lamellated/laminated, and outer fibrous layer. Inflammatory reaction around the cyst was variable and was characterized by an inner zone of loosely arranged fibroblasts infiltrated with mononuclear cells, followed by densely arranged fibroblasts along with mononuclear cells; and an outer layer of fibrous connective tissue. Fibroplasia and calcification were noted at places. In liver besides the cellular reaction against the expanding cyst, hepatocellular degeneration and cirrhosis were observed, the severity of which was inversely related to the distance from the cyst. The structural details of the protoscolices were clearly discernable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a zoonotic infection caused by larval forms (metacestodes) of the tapeworm Echinococcus. The World Health Organization has declared echinococcosis as a neglected zoonosis subgroup in its recent strategic plans for the regulation of tropical diseases that are neglected (da Silva 2010). CE is still an a challenge in the medical field and endemic in many countries across the world (Young 2005). Echinococcosis has carnivores (such as dogs) as definitive hosts and the herbivores and omnivores as intermediate hosts. Humans are infected accidently and are not a part of the natural life cycle of parasite. The adult worm, Echinococcus, develops in the small intestine of carnivores and intermediate stage hydatid cyst develops in the internal organs (mainly the liver and lungs) of humans and herbivores (sheep, horses, cattle, pigs, goats and camels) as fluid-filled bladders which are unilocular in nature (Ould et al. 2010). It’s pathogenicity depends upon the severity of the infection and the organ infected (Kebede et al. 2009). There are six species of Echinococcus: E. granulosus, E. multilocularis, E. vogeli, E. oligarthrus,, E. felidis and E. shiquicus (Hansen 1991). The latter Echinococcus species i.e. E. shiquicus and E. felidis are the recently discovered species which have been respectively isolated from the Tibetan mammals and African lions (Xiao et al. 2005; Huttner et al. 2008). Four species among the six known, E. multilocularis, E. granulosus, E. vogeli and E. oligartrus pose a severe threat to the human health (Johannes and Deplazes 2004; Pedro and Peter 2009).

Echinococcosis presents a serious public health problem (Lahmar et al. 2012) especially in the rural areas where the dogs are found in close association with man and other domestic animals, feeding on scraps and intestines of herbivores (Tilahun and Terefe 2013). Though the disease in domestic animals does not show major clinical signs and is detected only at the time of post-mortem yet it causes great economic losses by way of condemnation of livers and other organs besides lowered meat and milk production (Torgerson 2003). CE usually develops silently over decades until it surfaces with various clinical signs. Clinical symptoms are directly related to the location, size, and load of cysts present (Zhang et al. 2014).

Echinococcosis is diagnosed by different ways using X-ray, CT scan, immunological and serological tests including modern diagnostic technique i.e. polymerase chain reaction (PCR). It’s larval stage forms can usually be detected visually in organs. Microscopic examination of the tissue may confirm the diagnosis after the formalin-fixed tissue is processed by various conventional staining methods. The presence of a PAS positive and acellular layer with or without a cellular, germinal membrane that is nucleated can be considered as a characteristic of metacestodes of the Echinococcus (OIE 2008). The present study was envisaged to study histopathological and histochemical changes associated with cystic echinococcosis in sheep.

Materials and methods

Study material

The present study was conducted from the year 2013–2016 on locally reared sheep, including both slaughtered and naturally dead cases in different regions of Kashmir valley. Out of total 2100 heads screened, only 85 cases showed one or more cysts in lungs and livers.

Gross pathology

The affected organs were examined for any gross alterations associated with the cysts.

Histopathology

Representative tissue samples associated with hydatid cyst in different organs were collected and preserved in 10% formalin. The fixed tissue samples were processed by routine paraffin embedding technique. Briefly, the samples were cut into pieces of thickness 2–3 mm and washed under water for a few hours prior to dehydrating in ascending grades of alcohol and later cleared in benzene and embedded in paraffin. Tissue sections of 4–5 µm thickness were stained using the Harri’s Haematoxilin and Eosin method (Luna 1968).

Results

Gross pathology

Grossly, the lungs revealed single to multiple hydatid cysts of varying sizes. These were usually of table tennis ball shape but occasionally were as big as a cricket ball. The cysts were either fully embedded in the lung parenchyma or were partially embedded when they were visible from the lung surface. Both, dorsal and ventral aspect of the lungs were affected. Diaphragmatic lobe of the lung was frequently affected. Single to multiple cysts of varying size were observed from the visceral and/or parietal surfaces of liver. In general the cysts were soft and doughy to touch and were filled with clear to slightly turbid fluid. On aspiration of fluid, the cyst collapsed and the cyst membrane, appearing creamy white, could be easily removed from the organ and its fluid contents were found clear to slightly turbid. However, some cysts were appearing firm and contained inspissated contents. Also, some cysts were calcified, gritty and hard to cut (Fig. 1). The liver was observed to be the most frequently infected organ with relative prevalence of 61.17% followed by lungs (38.82%). The pulmonary cysts were mostly fertile (55%) compared to hepatic cysts (45%).

Histopathology

Lung

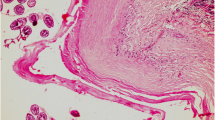

The cysts consisted of a thin inner germinal layer followed by laminated layer and an outer adventitial layer. Parasitic membranes (laminated membranes and germinal layers) were obvious in most examined sections, some were continuous and intact containing brood capsules with protoscolices (Fig. 2). Occasionally the cyst membrane was disrupted while in others only remnants of the membranes, and degenerated protoscolices were observed. In fertile hydatid cysts the germinal layer consisted of thick eosinophilic layer from which buds of brood capsules, containing potoscolices, projected into the cyst lumen. Laminated membranes varied with respect to thickness and number of laminations. Occasionally the laminated membrane was shrunk due to encroaching surrounding cellular reaction. The adventitial layer adjoining the laminated layer often showed variable features even within a single cyst. The inflammatory reaction, consisting of eosinophils, mononuclear cells, was seen immediate to the cyst layer and often extended into the surrounding alveoli (Fig. 3) and even to the adjacent terminal and small bronchioles. The lung parenchyma adjacent to the cysts was atelectatic or emphysematic and showed congestion and haemorrhage as well. In the majority of cases, whether the hydatid cyst was intact or degraded, segments of pulmonary parenchyma was visible. In some cases these sections were adjoining with palisading macrophages, eosinophils, epithelioid cells and multinucleated giant cells. The giant cells were either round oval or fusiform with nuclear pattern resembling the Langhan’s type of giant cell (Fig. 4). The degenerated hydatid cyst was surrounded by concentrically arranged mature fibrous tissue or early reactive fibroplasias. In some cases, there were foci of mineralization in the adventitial layer of the cyst (Fig. 5). Some cysts revealed numerous macrophages in multiple layers immediate to cyst membrane which was then surrounded by loose fibrillar layer followed by bundles of fibrous tissue. The associated changes in the lung were severe infiltration of eosinophils and alveolar macrophages in the bronchioles and alveoli. Peribronchiolar lymphoid hyperplasia, and bronchiolar epithelial hyperplasia were the additional findings (Fig. 6).

Liver

The histological picture of the hydatid cyst in liver resembled to that in the lung. The cyst had a laminated membrane revealing presence of numerous protoscolices from within or outside the brood capsule. The cyst wall was surrounded by the adventitial layer which in turn was surrounded by the inflammatory cells comprising of eosinophils, mononuclear cells and a few fibroblasts. The adjacent liver parenchyma showed haemorrhages. The laminated cysts wall was soetimes surrounded immediately by macrophage cell layer followed by a layer of infiltrating cells of eosinophils and mononuclear cells and then followed by fibroblastic cell layer (Fig. 7). Occasionally in chronic cases fibroplasia was more evident adjacent to the cysts, when the disrupted hepatocytes were evident in between the proliferating fibrous tissue. In such cases the fibroplasia was even seen in the portal triads resembling the portal cirrhosis. The hepatocytes revealed severe degenerative changes and pyknotic nuclei. Biliary hyperplasia and degenerative changes in biliary epithelium along with infiltration of inflammatory cells were observed in some liver affected with hydatidosis.

Discussion

Gross pathology

Grossly, the lungs revealed single to multiple hydatid cysts of variable size, either fully or partially embedded in the lung parenchyma especially in the diaphragmatic lobes. Both, dorsal and ventral aspects of the lungs were affected. Similar findings have been reported by investigators from other places (Canda et al. 2003; Rashed et al. 2004; Ibrahim and Gameel 2014). Lung parenchyma being spongy with greater capillary bed, besides favouring a greater distribution of onchospheres provides a more space for development of larger embedded cysts (Njoroge et al. 2002; Fakhar and Sadjjadi 2007; Ernest et al. 2009; Kebede et al. 2009). The cysts were soft with clear to slightly turbid fluid. While others were inspissated, caseated or calcified. Similar observations had been made by Ibrahim and Gameel (2014). It is opined that doughy cysts with inspissated contents observed in some cases probable reflect an attempt on part of the host to contain the cyst development. Such efforts might have favoured the degeneration and calcification of the cyst with advanced age. Single or multiple, mostly small to medium sized, partially or fully embedded cysts were observed on both parietal and visceral surfaces of liver (Anwar et al.1999). Liver has been regarded as one of the most favoured sites for development of hydatid cyst (Kebede et al. 2009). However, depending upon the immune competence of the host, the compact tissue resists development of larger cysts and favours cyst calcification (Torgerson 2003). Seadawy and Al-Kaled (2012) reported calcifications, blood patches, inflammatory zone around cysts and pale margins of liver.

Histopathology

Earlier studies have shown that the initial development of the cyst is achieved very quickly (within 10–14 days) but its growth is slow being achieved in a variable time, depending on the species of the infected animal, its age and location. The time required for formation of fertile cysts with complete structure is minimum 10 months in most species (Mitrea 1998; Thompson and Lymbery 1988). In the present study the cyst wall in lung presented the characteristic trilaminar structure with germinal membranes and brood capsules, and free scolex as reported earlier by (Ibrahim and Gameel 2014). Solcan et al. (2010) observed that in case of lungs, hydatid cyst wall, from inside to outside was composed of germinal membrane, laminated membrane and pericyst. There is a space between pericyst and ectocyst through which the tissue fluid and the nutrient medium flows. This space is the place of precipitation for neutral and acid polysaccharide, especially in sheep. The laminated membrane varied in thickness and in some sections was not clearly visible. The degenerated laminated membranes, presently observed, were associated with heavy infiltration of inflammatory cells in the inner side of the fibrous capsule. These features have been previously described by earlier workers (Barnes et al. 2011; Kul and Yildiz 2010; Verma and Swamy 2009).

The inflammatory reaction, consisting of infiltrating eosinophils, mononuclear cells, epithelioid cells and the multinucleated giant cells, were seen immediate to the cyst wall and oftenly extended into the surrounding alveoli. Adjacent to the cysts lung parenchyma was atelectatic or emphysematic and showed congestion and haemorrhage as well. Sakamoto and Gutierrez (2005) reported that many granulocytes, mainly derived from infiltrating eosinophils, were in the border zone between the laminated and adventitial layers and the adventitial layer surrounding the echinococcal cyst comprised an anuclear fibrous zone and a connective tissue zone and hemorrhagic foci and congestion was in the border zone between the adventitia and the lung tissue. Histopathological picture of the cysts in liver was similar to that observed in lungs (Anwar et al. 1999; Rashed et al. 2004; Ibrahim and Gameel 2014). Liver sections prepared from the areas neighbouring the cyst wall showed congestion, haemorrhage, hepatocyte necrosis and atrophy together with fibrosis and cellular infiltration of mainly macrophages, lymphocytes and plasma cells seen mostly in the inner side of the fibrous capsule which appeared broad as reported earlier by Singh et al. (2014). There was dilatation of sinusoids, and in central veins. Fibrosis was, also, seen in the portal area as reported earlier by Ibrahim and Gameel (2014). Further, the extensive fibroplasia and cirrhosis observed in some cases was attributed to immunological reactions of the host tissue (Khadidja et al. 2014). Biliary hyperplasia and degenerative changes in biliary epithelium along with infiltration of inflammatory cells were observed in some affected livers which is in accordance with Solcan et al. (2010).

In conclusion, gross and histopathological examinations constitute a golden tool for postmortem diagnosis of hydatidosis. However, epidemiological monitoring and surveillance in economically important animals warrants development of field oriented diagnostics. Also, the pathogenicity to the individual cysts is variable and related to the age of the cysts.

References

Anwar Z, Tanveer A, Bashir S (1999) Echinococcus granulosus: histopathology of naturally infected sheep liver. Punjab Univ J Zool 14:105–111

Barnes TS, Hinds LA, Jenkins DJ, Bielefeldt-Ohmann H, Lightowlers MW, Coleman GT (2011) Comparative pathology of pulmonary hydatid cysts in macropods and sheep. J Comp Pathol 144:113–122

Canda MS, Ray MG, Canda TL, Astarcioúlu HS (2003) The pathology of echinococcosis and the current echinococcosis problem in Western Turkey (A report of pathologic features in 80 cases). Turk J Med Sci 33:369–374

da Silva A (2010) Human echinococcosis: a neglected disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract 6:1–9

Ernest E, Nonga HE, Kassuku AA, Kazwala RR (2009) Echinococcosis of slaughtered animals in Ngorongoro district of Arusha region, Tanzania. Trop Anim Health Prod 41:1179–1185

Fakhar M, Sadjjadi SM (2007) Prevalence of hydatidosis in slaughtered herbivores in Qom Province, Central Part of Iran. Vet Res Com 31:993–997

Hansen B (1991) New York City epidemics and history for the public. In: Harden VA, Risse GB (eds) AIDS and the historian. Bethesda, National Institutes of Health, pp 21–28

Huttner M, Nakao M, Wassermann T, Siefert L, Boomker JD (2008) Genetic characterization and phylogenetic position of Echinococcus felidis (Cestoda: Taeniidae) from the African lion. Int J Parasitol 7:861–868

Ibrahim SEA, Gameel AA (2014) Pathological, histochemical and Immunohistochemical studies of lungs and livers of cattle and sheep infected with hydatid disease. In: Proceedings of 5th annual conference-agricultural and veterinary research–February 2014, Khartoum, Sudan, vol 2, pp 1–17

Johannes E, Deplazes P (2004) Biological, Epidemio-logical, and clinical aspects of echinococcosis, a zoonosis of increasing concern. Clin Microbio Rev 17:107–135

Kebede N, Mitiku A, Tilahun G (2009) Echinococcosis of slaughtered animals in Bahir Dar Abattoir, Northwestern Ethiopia. Trop Anim Health Prod 41:43–50

Khadidja H, Achour Y, Houcin B, Vasile C (2014) Histological Appearance of Echinococcus Granulosus in the Camel Species in Algeria. Bulletin UASVM Vet Med 71:79–84

Kul O, Yildiz K (2010) Multivesicular cysts in cattle: Characterisation of unusual hydatid cyst morphology caused by Echinococcus granulosus. Vet Parasitol 170:162–166

Lahmar S, Trifi S M, Ben-Naceur S, Bouchhima T, Lahouar N, Lamouchi I, Maamouri N, Selmi R, Dhibi M, Torgerson PR (2012) Cystic echinococcosis in slaughtered domestic ruminnats from Tunisia. J Helminthol 87:1–8

Luna LG (1968) Manual of histologic staining methods of the Armed forces, Institute of Pathology, 3rd edn. Mc Graw Hill Book Company, New York

Mitrea IL (1998) Research regarding immunodiagnostics, immune response and immune prophylaxis in hydatidosis in ruminants [In Romanian]. PhD thesis, USAMV Bucharest, Romania

Njoroge EM, Mbithi PM, Gathuma JM, Wachira TM, Magambo JK, Zeyhle EA (2002) Study of cystic echinococcosis in slaughter animals in three selected areas of northern Turkana, Kenya. Vet Parasitol 104:85–91

OIE (2008) Echinococcosis/hydatidosis. OIE terrestrial manual pp 175–190

Ould CB, Schneegans F, Chollet JY, Jemli MH (2010) Prevalence and aspects of lesions of echinococcosis in camel in Northern Mauritania. Revue Elev Méd Vét Pays Trop 63:23–28

Pedro M, Peter MS (2009) Echinococcosis: a review. Int J Infect Dis 13:125–133

Rashed AA, Omer HM, Fouad MAH, Al-Shareef AMF (2004) The effect of severe cystic hydatidosis on the liver of a Najdi sheep with special reference to the cyst histology and histochemistry. J Egypt Soc Parasitol 34:297–304

Sakamoto T, Gutierrez C (2005) Pulmonary complications of cystic echinococcosis in children in Uruguay. Pathol Int 55:497–503

Seadawy MAH, Al-Kaled MJA (2012) Gross and histological comparison of hydatid cyst infection in livers of sheep and cows. AL-Qadisiya J Vet Med Sci 11(2):1643–1646

Singh BB, Sharma R, Sharma JK, Mahajan V, Gill JPS (2014) Histopathological changes associated with E. granulosus echinococcosis in food producing animals in Punjab (India). J Parasit Dis 40:1–3

Solcan C, Solcan G, Ioniţă M, Hristescu DV, Mitrea IL (2010) Histological aspects of cystic echinococcosis in goats. Sci Parasitol 11:191–198

Thompson RCA, Lymbery AJ (1988) The nature, extent and significance of variation within the genus Echinococcus. Adv Parasitol 27:209–258

Tilahun A, Terefe Y (2013) Echinococcosis: prevalence, cyst distribution and economic significance in cattle slaughtered at Arbaminch municipality abattoir, Southern Ethiopia. Glob Vet 11:329–334

Torgerson PR (2003) The economic effects of echinococcosis. Acta Trop 85:113–118

Verma Y, Swamy M (2009) Prevalence and pathology of hydatidosis in buffalo liver. Buffalo Bull 28:207–211

Xiao N, Qiu JM, Nakao M, Li TY, Yang W (2005) Echinococcus shiquicus n.sp., a taeniid cestod from Tibetan fox and plateau pika in China. Int J Parasitol 35:693–701

Young ED (2005) Brucella species. In: Mandell GL, Douglos RG, Bennett JE (eds) Principles and practice of infectious disease, 6th edn. Churchill Livingstone, Pensylvania, pp 3290–3292

Zhang T, Yang D, Zeng Z, Zhao W, Liu A, Piao D, Jiang T, Cao J, Shen Y, Liu H, Zhang W (2014) Genetic characterization of human-derived hydatid cysts of Echinococcus granulosus Sensu Lato in Heilongjiang Province and the first report of G7 genotype of E. canadensis in humans in China. PLoS ONE 9:10

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Study conception and design: A. B. Beigh, M.M. Darzi. Acquisition of data: A. B. Beigh. Analysis and interpretation of data: B. kashani, A. Shah. Drafting of manuscript: S. Bashir. Critical revision: S. Shah.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no personal or financial relationships between the authors and other people or organizations which have inappropriately influenced this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Beigh, A.B., Darzi, M.M., Bashir, S. et al. Gross and histopathological alterations associated with cystic echinococcosis in small ruminants. J Parasit Dis 41, 1028–1033 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12639-017-0929-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12639-017-0929-z