Abstract

In mammals, LPS regulate feeding primarily through the 5-HT1A and 5-HT2c receptors within the brain. However, the central effect of 5-HT1A and 5-HT2c on LPS-induced feeding behavior has not been studied in non-mammalian species. Also, the role of glutamatergic system in LPS-induced anorexia has never been examined in either mammalian or non-mammalian species. Therefore, in this study, we examined the role of serotonergic and glutamatergic systems on LPS-induced anorexia in chickens. Food intake was measured in chickens after centrally administered lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (20 ng) (0 h), followed by intracerebroventricular (ICV) injection of the 5-HT1A autoreceptor agonist (8-OH-DPAT, 61 nmol), 5-HT2c receptor antagonist (SB 242084, 30 nm), and NMDA receptor antagonist (DL-AP5, 5 nm) at the onset of anorexia (4 h). In the following experiments, we used DL-AP5 before 5-HT (10 μg) and SB242084 before glutamate (300 nm) for evaluation of the interaction between 5-HTergic and glutamatergic systems on food intake. The results of this study showed that SB 242084 and DL-AP5 significantly attenuated food intake reduction caused by LPS (P < 0.05) but 8-OH-DPAT had no effect. In addition, 5-HT-induced anorexia was significantly attenuated by DL-AP5 pretreatment (P < 0.05), while SB 242084 had no effect on glutamate-induced hypophagia. These results indicated that 5-HT and glutamate (via 5-HT2c and NMDA receptor, respectively) dependently regulate LPS-induced hypophagia in chickens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The appetite regulatory network is modulated at the hypothalamic level by the interaction of hormonal and neuronal signaling [1]. Aminergic neurotransmitters have long been implicated in feeding control at the hypothalamic level [2]. Glutamate and serotonin (5-HT), two major excitatory neurotransmitters in the central nervous system (CNS), have been suggested to be the endogenous agents involved in the neural control of food intake and body weight in mammals [3] and birds [4–6]. Glutamate receptors have been found to be widely distributed in the avian CNS [7], and can be involved in learning and memory processes, as well as neuroendocrine control mechanism, in chickens [8]. In opposition to mammals, it has been shown that intracerebroventricular injection of glutamate in 24-h food-deprived pigeons and chickens decreases food intake in a dose-dependent manner [4, 5, 9]. Early investigations showed that increased circulating tryptophan availability (initial precursor of 5-HT synthesis) or centrally administration of tryptophan promotes satiety in birds [3, 10, 11]. Increase of 5-HTergic transmission by treatment with 5-HT releasers also has inhibitory influence on feeding behavior [12]. The participation of 5-HT2c and NMDA receptors in the anorectic response has been reported in birds [4, 9, 12].

Lipopolysaccharides (LPS) from Gram-negative bacterial cell walls are major promoters of the acute phase response and reduce food intake after parenteral administration in animals [13]. The food intake reduction during bacterial infections is most likely the result of complex neural, neurohumoral, and endocrine interactions between bacterial products and endogenous mediators in the periphery as well as in the brain. Several cytokines, like tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and interleukin (IL)-1, are supposed to play a role as endogenous mediators of the hypophagic effects of bacterial products such as LPS [14]. Both LPS and IL-1β increase 5-HTergic activity in the brain when injected peripherally [15] or centrally [16]. On the other hand, it has been reported that the specific 5-HT1A autoreceptor agonist 8-hydroxy-2-(Di-N-propylamino) tetraline (8-OH-DPAT) and the specific 5-HT2c receptor antagonist (SB 242084) attenuate the anorexia following peripheral administration of LPS in rats, suggesting that an increase in 5-HTergic activity is involved in mediating the feeding suppressive effect of peripheral LPS [17]. It has also been suggested that LPS could alter central glutamatergic activity via cytokines like TNF-α and contribute to pathophysiological conditions in mammals [18–20]. Nevertheless, the role of 5-HTergic and glutamatergic systems in LPS-induced anorexia has never been examined in chickens.

In the present study, we provide evidence indicating involvement of the 5-HTergic and glutamatergic systems in LPS-induced feeding behavior in chickens. To this end, we examined the intracerebroventricular injection of DL-AP5 (NMDA) receptor antagonist, specific 5-HT1A autoreceptor agonist (8-OH-DPAT), and 5-HT2c receptor antagonist (SB 242084) on LPS-induced anorexia in chickens.

Materials and methods

Animals

Chickens (Eshragh, Iran) were reared in heated batteries with continuous lighting until 3 weeks of age. Birds were provided with a mash diet (21 % protein and 2,869 kcal/kg of metabolizable energy) and water ad libitum. At approximately 2 weeks of age, the birds were transferred to individual cages. The temperature and relative humidity of the animal room were maintained at 22 ± 1 °C and 50 %, respectively, in addition to the continuous lighting condition [21].

Drugs

Drugs used included LPS from Escherichia coli, serotype 0111: B4 (No. L-2630; Sigma), 5-HT1A-autoreceptor agonist 8-hydroxy-2-(Di-N-propylamino) tetraline (8-OH-DPAT)(No. L-57H4131; Sigma), 5HT2c receptor antagonist (SB 242084) (No. L-060K4608; Sigma), DL-AP5 (NMDA receptor antagonist) (Tocris Cookson, Bristol, UK), glutamate (Tocris Cookson) diluted in pyrogen-free 0.9 % NaCl solution (saline) that served as control. Doses of LPS, 8-OH-DPAT, SB 242084, DL-AP5, and glutamate were chosen on the basis of previous [4–6, 17, 22] and preliminary studies.

Surgical preparation

At 3 weeks of age, chickens were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (Sagatal; Rhone Merieux) (25 mg/kg body weight, i.v.), and a 23-gauge thin-walled stainless steel guide cannula was stereotaxically implanted into the right lateral ventricle, according to the technique previously described by Denbow et al. [23]. The stereotaxic coordinates were AP = 6.7, L = 0.7, H = 3.5–4 mm below the dura matter with the head oriented as described by Van Tienhoven and Juhaz [24]. The cannula was secured with 3 stainless steel screws placed in the calvaria surrounding each guide cannula, then acrylic dental cement (Pars acryl) was applied to the screws and guide cannula. An orthodontic # 014 wire (American Orthodontics) trimmed to the exact length of the guide cannula was inserted into the guide cannula while the chicks were not being used for experiments. Lincospectin (Razak) was applied to the incision to prevent infection. The birds were allowed a minimum of 5 days recovery prior to injection.

Experimental procedures

For the possible involvement of 5-HTergic and glutamatergic systems in the brain in LPS-induced eating response, the effects of centrally administered 8-OH-DPAT, SB 242084, DL-AP5, and glutamate on LPS-induced eating response was determined in chickens. Injections were made with a 29-gauge, thin-walled stainless steel injecting cannula which extends 1.0 mm beyond the guide cannula. This injecting cannula was connected through a 60-cm-long PE-20 tubing to a 10-μl Hamilton syringe. Tubing and syringes were kept in 70 % ethanol. Solutions were injected over a period of 60 s. A further 60-s period was allowed to permit the solution to diffuse from the tip of the cannula into the ventricle. All experimental procedures were performed between 0800 and 1600 hours. Before injection, the birds were removed from their individual cages, restrained by hand, then put back into their cages immediately after the injections. Birds were handled and mock-injected daily during the 5-day recovery period, in order to get used in the injection procedure. Chickens received food and water ad libitum. Placement of the guide cannula into the ventricle was verified by the presence of cerebrospinal fluid and intracerebroventricular injection of methylene blue followed by slicing the frozen brain tissue at the end of the experiments.

In this study, Experiment 1 was performed to examine the effect of ICV injection of LPS on food intake in chickens (n = 7–9 for each group). The birds received 5, 10, and 20 ng LPS in 10 μl saline. The control group was injected with 10 μl of saline. Fresh food was supplied at the time of injection, and food intake (g) was recorded at 2, 4, 6, and 8 h after injection.

In Experiment 2, chickens were used to test the effect of 8-OH-DPAT on ICV LPS-induced anorexia. Each bird received two injections. The first injection consisted of either 0 or 20 ng LPS in 5 μl saline. The second injection consisted of either 0 or 61 nmol 8-OH-DPAT in 5 μl saline, at the onset of anorexia (4 h after the first injection) (n = 7–9 for each group). Food intake (g) was recorded at 0–2 and 0–4 h after the onset of anorexia.

Experiment 3 was designed to test the effect of SB 242084 on ICV LPS-induced anorexia. Each bird received two injections. The first injection consisted of either 0 or 20 ng LPS in 5 μl saline. The second injection consisted of either 0 or 30 nm SB 242084 in 5 μl saline, at the onset of anorexia (4 h after the first injection). Food intake (g) was recorded at 0–2 and 0–4 h after the onset of anorexia.

Experiments 4 was conducted similarly to the second experiment except that the chicks received 0 or 5 nmol DL-AP5 instead of 8-OH-DPAT, and food intake (g) was recorded at 0–2 and 0–4 h after the onset of anorexia.

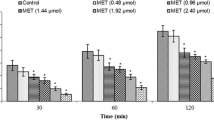

Experiment 5 was designed to evaluate the effect of DL-AP5 on ICV 5-HT-induced anorexia. Each bird received two injections with a 15-min interval between them. The first injection consisted of either 0 or 5 nmol DL-AP5 in 5 μl saline. The second injection consisted of either 0 or 10 μg 5-HT in 5 μl saline. Cumulative food intake (g) was recorded at 1, 2, 3, and 4 h after the second injection.

In Experiment 6, chickens were used to test the effect of SB 242084 on ICV glutamate-induced anorexia. The experimental procedure was similar to the 5 other experiments except that the chicks received 0 or 30 nmol SB 242084 instead of DL-AP5 and 0 or 300 nmol glutamate instead of 5-HT.

Statistical analysis

Cumulative food intake was analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), and is presented as mean ± SEM, for treatment showing a main effect by ANOVA, means have compared by post hoc Bonferroni and Dunnett tests. P ≤ 0.05 was considered as a significant difference between treatments.

Results

The food intake response to ICV injection of LPS, 8-OH-DPAT (5-HT1A autoreceptor agonist) and SB242084 (5HT2c receptor antagonist), DL-AP5 (NMDA receptor antagonist), and glutamate in chickens is presented in Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6.

In Experiment 1, during the 0–2 h period after ICV administration of LPS or saline, average food intake of both groups was between 9 and 12 g regardless of treatment. ICV LPS (5, 10, and 20 ng) significantly reduced cumulative food intake between 4 and 8 h after LPS injection in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1) (P < 0.05). We did not observe endotoxic effects and other behavioral changes in chickens after ICV administration of LPS.

In Experiment 2, 8-OH-DPAT appeared to attenuate the ICV LPS- induced anorexia between 4 and 6 h (0–2 h after 8-OH-DPAT) and 4–8 h (0–4 h after 8-OH-DPAT), but this difference was not significant (Fig. 2) (P > 0.05).

In Experiment 3, SB 242084 attenuated the LPS-induced anorexia significantly between 4 and 6 h (0–2 h after SB 242084) and 4–8 h (0–4 h after SB 242084) (Fig. 3) (P < 0.05).

In Experiment 4, DL-AP5 attenuated the LPS-induced anorexia significantly between 4 and 6 h (0–2 h after DL-AP5) and 4–8 h (0–4 h after DL-AP5) (Fig. 4) (P < 0.05).

In Experiments 5 and 6, 5-HT induced anorexia was significantly attenuated by DL-AP5 pretreatment (Fig. 5) (P < 0.05); but SB 242084 had no effect on feeding behavior induced by glutamate (Fig. 6) (P > 0.05).

Discussion

The first experiment examined the hypophagic effect of intracerebroventricularly administered LPS in chickens. In accordance with previous studies [13, 17], parenteral administration of LPS resulted in reduced food intake. Kerryn et al. [25] reported that peripheral injection of LPS in chickens leads to reduced appetite. The new finding in the present study is the central feeding behavior of LPS with respect to its hypophagic effect. The mechanisms by which LPS treatments decrease appetite in birds have not been fully elucidated. Many of the physiological effects of LPS are mediated by cytokines, like TNF- α and interleukin (IL)-1, which are released from activated cells of monocyte/macrophage lineage [26–28]. TNF-α, IL-1α, and IL-1β potently reduce food intake after either peripheral or central administration in mammals [29], and are therefore implicated in the hypophagic effect of LPS.

The results obtained in Experiments 2 and 3 showed that both ICV injections of 8-OH DPAT, 5-HT1A receptor agonist, and SB 242084, 5-HT2c receptor antagonist, increase food intake in comparison with control group, but only the administration of SB 242084 had significant effect. Our findings are consistent with previous reports that have shown a physiological correlation between 5-HTergic system activity and control of feeding behavior in birds [6, 10]. In fowls, a dense 5-HTergic -fiber distribution has been identified in diencephalic regions known to be involved in controlling feeding behavior [30], and binding sites for classical 5-HTergic agonists have been described [31]. In Experiment 2, we showed that the activation of 5-HT1A receptors induce a non-significant increase of food intake in satiated chickens. This finding is similar to a previous study that suggested that the agonist 8-OH-DPAT did not significantly alter the food intake when the chickens were fed 60 min before the injection, while it stimulates feeding in fasted then re-fed ones [32]. In another study with chickens from a low-growth strain (layer strain), it has been reported that the agonist 8-OH-DPAT, injected intravenously, stimulates feeding in fed ones [31]. It was found that the 5-HT1A receptor agonists produce hyperphagia in non-deprived rats and pigs [33, 34]. Our results are contrary to the observed effects in mammals and in layer-strain chickens, because, probably, the selection for rapid growth rate in chickens causes modifications in the feeding control pattern. The result obtained in Experiment 3 is in agreement with Cedraz-Mercez et al. [12] who showed that treatment with 5-HT2C receptor agonists induce significant inhibition of food intake in fasted or normally fed fowls. Thus, the hyperphagic responses achieved with SB242084, which is a powerful 5-HT2C antagonist, provide evidence of the central mediation of appetite by 5-HT.

In Experiment 2, we found that central activation of 5-HT1A receptors by 8-OH-DPAT had no effect on LPS-induced anorexia, which is consistent with previous studies in rat [17]. In contrast, Hrupka and Langhans [35] suggested that injection of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist, 8-OH-DPAT directly into the midbrain raphe ameliorated the LPS-induced hypophagia. In Experiment 3, inhibition of 5-HT2c receptors by SB 242084 significantly attenuated the food intake reduction caused by LPS between 0–2 and 0–4 h after onset of anorexia (Fig. 3). Our finding is in line with previous reports in mammals [17, 35, 36] showing that 5-HT2C receptor blockade by SB 242084 attenuate central and peripheral LPS- induced anorexia. These controversial effects of 5-HT receptors on LPS anorexia may be related to their different way of action. For instance, most 5-HT1A receptors are somatodendritic autoreceptors with a negative-feedback function, while it has been suggested that SB 242084 completely blocks the LPS-induced increases in C-Fos expression in the several areas of brain that are involved in food intake, such as the paraventricular nucleus, and partially suppresses it in the A1 noradrenergic area of the ventrolateral medulla [36]. Numerous studies also implicate central 5-HT in LPS anorexia. The ratios of the 5-HT catabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid to 5-HT were elevated 2 h after intraperitoneal LPS injection both in the hypothalamus and brain stem, indicating increased 5-HT release [37]. In this regard, Dunn et al. [15] reported that LPS-induced anorexia is mediated via cytokines like IL-1 and TNF-α, and that these cytokines increase serotonin release in brain. IL-1 receptors are present on the POMC neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus which release α-MSH [38]. Ultimately, α-MSH activation of melanocortin receptor 4 results in reduced food intake [38, 39]. On the other hand, it is believed that melanocortin circuitry is a primary mechanism underlying 5-HT’s effects on energy balance [4, 12]. Taken together, it is possible to speculate that 5-HT augmentation in infectious diseases promotes hypophagia. These results collectively demonstrate the potential involvement of central 5-HT2c receptors in LPS-induced hypophagia in chickens.

In this study, we provide the first evidence that a glutamatergic system in the brain may be involved in the genesis of LPS-induced hypophagia in chicks. The results obtained from Experiment 4, which show that the blockage of NMDA receptors increase food intake in chickens, are in line with earlier findings [4, 9]. Furthermore, these findings, and the results obtained from Experiments 5 and 6 ,confirm our previous studies and other findings which have shown that intracerebroventricular infusion of glutamate inhibits food intake in chickens [4, 5, 9]. Glutamate, a major excitatory neurotransmitter in the CNS, has been suggested to be an endogenous agent involved in the neural control of food intake and body weight [3]. In Experiment 4, the decreased food consumption induced by the intracerebroventricular injection of LPS was attenuated by application of DL-AP5. It showed that the inhibitory effect of LPS on food intake is modulated by the pathway(s) linked to the NMDA receptor. Several lines of evidence suggest that glutamatergic system may be involved in the pathophysiological effects of LPS [41–43]. For instance, the LPS-induced fever could be mimicked by direct injection of glutamate into the rabbit’s brain and pretreatment with NMDA-receptor antagonists effectively suppresses this effect [39, 40]. It is well known that many of the physiological effects of LPS are mediated by cytokines which are released from activated mononuclear cells [26–28, 42]. Takeuchi et al. [18] showed that TNF-α is the key cytokine that stimulates extensive microglial glutamate release in an autocrine manner by up-regulating glutaminase and enhances excitotoxicity through stimulation of NMDA receptor [18]. Additionally, it has been demonstrated that hypothalamic cytokine elevations caused by systemic injection of LPS were significantly reduced by NMDA-receptor antagonists [42]. On the other hand, it has been revealed that phenotypes of many neurons in the arcuate nucleus are glutamatergic, and glutamate is involved in the innervation of arcuate neurons [43], a key site for the interaction between circulating agents and the CNS [3]. Therefore, it seems that LPS may interact with glutamatergic neurons of arcuate nucleus in the hypothalamus to suppress food intake in chickens. The results obtained from Experiments 3 and 4 showed that SB 242084 and DL-AP5 increased food intake without LPS. Thus, we cannot strongly indicate that LPS-induced hypophagia is mediated by 5-HT and glutamate. However, in Experiment 6, SB 242084 increased food intake alone, but cumulative food intake of glutamate was not altered by SB 242084 treatment. So, further studies may also be necessary to clarify whether or not LPS-induced hypophagia is mediated by 5-HT and glutamate.

The results obtained from Experiments 5 and 6 showed that the hypophagic effect of 5-HT was significantly attenuated by pretreatment with DLAP-5, but SB 242084 could not alter glutamate-induced anorexia. These data indicate that there is an interaction between 5-HT and glutamate (via NMDA receptors) on food intake in chickens. In this regard, approximately 60 % of 5-HTergic raphe neurons evoke excitatory post-synaptic potentials (EPSPs), indicating that most of these neurons in addition to 5-HT use glutamate as a co-transmitter [44]. Gandolfi et al. [45] reported that the effects mediated by NMDA and 5-HT2 receptors converge on the same signal transduction mechanism (phosphatidylinositol breakdown), and 5-HT2 receptor activation increases glutamate release and enhances the amplitude of glutamatergic EPSCs by inducing a sub-threshold sodium current in the neurons [46]. In the ventrobasal thalamus, 5-HT enhances both NMDA- and non-NMDA-mediated effects, and activation of 5-HT receptors modulates some typical NMDA-receptor-mediated behaviors [47]. Modulation of glutamate transmission by 5-HT has also been observed in other brain areas involved in different functions. For example, in the tractus solitarius nucleus [48], dorsal vagal motor nucleus [49], and area postrema [50], 5-HT stimulates glutamate release [51] that these areas are involved in feeding behavior. As discussed above, 5-HT modulates glutamate-mediated effects in CNS. Thus, based on these data, there is perhaps an interaction between 5-HTergic and glutamatergic systems (via 5-HT2c and NMDA receptors, respectively) on food intake. In addition, 5-HT and glutamate dependently regulate LPS-induced hypophagia. However, further studies may also be necessary.

References

Kalra SP, Dube MG, Pu S, Xu B, Horvath TL, Kalra PS (1999) Interacting appetite-regulating pathways in the hypothalamic regulation of body weight. Endocr Rev 20:68–100

Orlando G, Brunetti L, Di Nisio C, Michelotto B, Recinella L, Ciabattoni G, Vacca M (2001) Effects of cocaine- and amphetamine-regulated transcript peptide, leptin, and orexins on hypothalamic serotonin release. Eur J Pharmacol 430:269–272

Meister B (2007) Neurotransmitters in key neurons of the hypothalamus that regulate feeding behavior and body weight. Physiol Behav 92:263–271

Taati M, Nayebzadeh H, Zendehdel M (2011) The effects of DL-AP5 and glutamate on ghrelin-induced feeding behavior in 3-h food-deprived broiler cockerels. J Physiol Biochem 67:217–223

Zendehdel M, Baghbanzadeh A, Babapour V, Cheraghi J (2009) The effects of bicuculline and muscimol on glutamate-induced feeding behavior in broiler cockerels. J Comp Physiol A 195:715–720

Steffen SM, Casas DC, Milanez BC, Freitas CG, Paschoalini MA, Marino-Neto J (1997) Hypophagic and dipsogenic effects of central 5-HT injections in pigeons. Brain Res Bull 44(6):681–688

Ottiger HP, Gerin-Moser A, Del Principe F, Dutly F, Streit P (1995) Molecular cloning and differential expression patterns of avian glutamate receptor mRNAs. J Neurochem 64:2413–2426

Porter MH, Arnold M, Langhans W (1998) TNF-a tolerance blocks LPS-induced hypophagia but LPS tolerance fails to prevent TNF-a-induced hypophagia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 274:741–745

Zeni LA, Seidler HB, De Carvalho NA, Freitas CG, Marino-Neto J, Paschoalini MA (2000) Glutamatergic control of food intake in pigeons: effects of central injections of glutamate, NMDA, and AMPA receptor agonists and antagonists. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 65(1):67–74

Reis LC, Almeida AC, Cedraz-Mercez PL, Olivares EL, Marinho JRA, Thomaz CM (2005) Evidence indicating participation of the serotonergic system in controlling feeding behavior in Coturnix japonica (Galliformes: Aves). Braz J Biol 65(2):353–361

Simansky KJ (1996) Serotonergic control of the organization of feeding and satiety. Behav Brain Res 73:37–42

Cedraz-Mercez PL, Almeida AC, Costa-e-Sousa RH, Badauê Passos JD, Castilhos LR, Olivares EL, Marinho JA, Medeiros MA, Reis LC (2005) Influence of serotonergic transmission and postsynaptic 5-HT2C action on the feeding behavior of Coturnix japonica (Galliformes: Aves). Braz J Biol 65(4):589–595

Langhans W, Balkowski G, Savoldelli D (1991) Differential feeding responses to bacterial lipopolysaccharide and muramyl dipeptide. Am J Physiol 261:659–664

Laye S, Gheusi G, Cremona S, Combe C, Kelley K, Dantzer R, Parnet P (2000) Endogenous brain IL-1 mediates LPS-induced anorexia and hypothalamic cytokine expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 279:93–98

Dunn AJ, Wang J, Ando T (1999) Effects of cytokines on cerebral neurotransmission. Comparison with the effects of stress. Adv Exp Med Biol 461:117–127

Zubareva OE, Krasnova IN, Abdurasulova IN, Bluthe RM, Dantzer R, Klimenko VM (2001) Effects of serotonin synthesis blockade on interleukin-1β action in the brain of rats. Brain Res 915:244–247

Von Meyenburg C, Langhans W, Hrupka BJ (2003) Evidence that the anorexia induced by lipopolysaccharide is mediated by the 5-HT2C receptor. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 74:505–512

Takeuchi H, Jin S, Wang J, Zhang G, Kawanokuchi J, Kuno R, Sonobe Y, Mizuno T, Suzumura A (2006) Tumor necrosis factor-α induces neurotoxicity via glutamate release from hemichannels of activated microglia in an autocrine manner. J Biol Chem 281(30):21362–21368

Lin H, Wan FJ, Kang BH, Wu CC, Tseng CJ (1999) Systemic administration of lipopolysaccharide induces release of nitric oxide and glutamate and c-fos expression in the nucleus tractus solitarii of rats. Hypertension 33:1218–1224

Taguchi K, Tamba M, Bannai S, Sato H (2007) Induction of cystine/glutamate transporter in bacterial lipopolysaccharide induced endotoxemia in mice. J Inflamm (Lond) 4:20

Olanrewaju HA, Thaxton JP, Dozier WA, Purswell J, Roush WB, Branton SL (2006) A review of lighting programs for broiler production. Int J poultry Sci 5(4):301–308

Yakabi K, Sadakane C, Noguchi M, Ohno S, Ro S, Chinen K, Aoyama T, Sakurada T, Takabayashi H, Hattori T (2010) Reduced ghrelin secretion in the hypothalamus of rats due to cisplatin-induced anorexia. Endocrinology 151(8):3773–3782

Denbow DM, Cherry JA, Siegel PB, Van Kery HP (1981) Eating, drinking and temperature response of chicks to brain catecholamine injections. Physiol Behav 27:265–269

Van Tienhoven A, Juhaz LP (1962) The chicken telencephalon, diencephalons and mesencephalon in stereotaxic coordinates. J Comp Neural 118:185–197

Kerryn M, Sell Simon F, Crowe SK (2003) Lipopolysaccharide induces biochemical alterations in chicks trained on the passive avoidance learning task. Physiol Behav 78:679–688

Beutler B, Greenwald D, Hulmes JD (1985) Identity of tumor necrosis factor and the macrophage-secreted factor cachectin. Nature 316:552–554

Dinarello CA (1996) Biological basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood 87:2095–2147

Marinkovic S, Jahreis GP, Wong GG (1989) IL-6 modulates the synthesis of a specific set of acute phase proteins in vivo. J Immunol 142:808–812

Langhans W, Savoldelli D, Weingarten S (1993) Comparison of the feeding responses to bacterial lipopolysaccharide and interleukin-1beta. Physiol Behav 53:643–649

Sako H, Kojima T, Okado N (1986) Immunohistochemical study on the development of serotoninergic neurons in the chick: I. Distribution of cell bodies and fibers in the brain. J Comp Neurol 253:61–78

Saadoun A, Cabrera MC (2002) Effect of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT on food and water intake in broiler chickens. Physiol Behav 75:271–275

Saadoun A, Cabrera MC (2008) Hypophagic and dipsogenic effect of the 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT in chicken chickens. J Anim Physiol Anim Nutr (Berl) 92:597–604

Ebenezer IS (1992) Effect of the 5-HT1A agonist 8-OH-DPAT on food intake in food-deprived rats. Neuroreport 3:1019–1022

Ebenezer IS, Parrott RF, Vellucci SV (1999) Effect of 5-HT1A receptor agonist 8-OH-DPAT on food intake in food-deprived pigs. Physiol Behav 67:213–217

Hrupka BJ, Langhans W (2001) A role for serotonin in lipopolysaccharide-induced anorexia in rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 68:355–362

Kopf BS, Langhans W, Geary N, Asarian L (2010) Serotonin 2C receptor signaling in a diffuse neuronal network is necessary for LPS anorexia. Brain Res 1306:77–84

Dunn AJ (1992) Endotoxin-induced activation of cerebral catecholamine and serotonin metabolism: comparison with interleukin-1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 261:964–969

Scarlett JM, Jobst EE, Enriori PJ, Bowe DD, Batra AK, Grant WF, Cowley MA, Marks DL (2007) Regulation of central melanocortin signaling by interleukin-1 beta. Endocrinol 148:4217–4225

Huang QH, Hruby VJ, Tatro JB (1999) Role of central melanocortins in endotoxin induced anorexia. Am J Physiol 276(45):864–871

Huang WT, Tsai SM, Lin MT (2001) Involvement of brain glutamate release in pyrogenic fever. Neuropharmacology 41:811–818

Huang WT, Lin MT, Chang CP (2006) An NMDA receptor-dependent hydroxyl radical pathway in the rabbit hypothalamus may mediate lipopolysaccharide fever. Neuropharmacology 50:504–511

Kao CH, Kao TY, Huang WT, Lin MT (2007) Lipopolysaccharide- and glutamate-induced hypothalamic hydroxyl radical elevation and fever can be suppressed by N-methyl-d-aspartate-receptor antagonists. J Pharmacol Sci 104(2):130–136

Van den Pol AN, Trombley PQ (1993) Glutamate neurons in hypothalamus regulate excitatory transmission. J Neurosci 13:2829–2836

Johnson MD (1994) Synaptic glutamate release by postnatal rat serotonergic neurons in microculture. Neuron 12(2):433–442

Gandolfi O, Dall’Olio R, Roncada P, Montanaro N (1990) NMDA antagonists interact with 5-HT-stimulated phosphatidylinositol metabolism and impair passive avoidance retention in the rat. Neurosci Lett 113(3):304–308

Aghajanian GK, Marek GJ (1997) Serotonin induces excitatory postsynaptic potentials in apical dendrites of neocortical pyramidal cells. Neuropharmacology 36(4–5):589–599

Mjellem N, Lund A, Eide PK, Storkson R, Tjolsen A (1992) The role of 5-HT1A and 5-HT1B receptors in spinal nociceptive transmission and in the modulation of NMDA induced behaviour. Neuroreport 3(12):1061–1064

Ashworth-Preece MA, Jarrott B, Lawrence AJ (1995) 5-Hydroxytryptamine3 receptor modulation of excitatory amino acid release in the rat nucleus tractus solitarius. Neurosci Lett 191(1–2):75–78

Wang Y, Ramage AG, Jordan D (1998) Presynaptic 5-HT3 receptors evoke an excitatory response in dorsal vagal preganglionic neurones in anaesthetized rats. J Physiol 509(Pt 3):683–694

Funahashi M, Mitoh Y, Matsuo R (2004) Activation of presynaptic 5-HT3 receptors facilitates glutamatergic synaptic inputs to area postrema neurons in rat brain slices. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 26(8):615–622

Pickard GE, Smith BN, Belenky M, Rea MA, Dudek FE, Sollars PJ (1999) 5-HT1B receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition of retinal input to the suprachiasmatic nucleus. J Neurosci 19(10):4034–4045

Acknowledgments

This study was a DVM thesis supported by a grant from Research Council of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, University of Tehran. Animal handling and experimental procedures were performed according to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals published by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH publication NO.85-23, revised 1996) and also with the current laws of Iran.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Zendehdel, M., Taati, M., Jonaidi, H. et al. The role of central 5-HT2C and NMDA receptors on LPS-induced feeding behavior in chickens. J Physiol Sci 62, 413–419 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-012-0218-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-012-0218-7