Abstract

Objectives

Hip fracture is one of the most common public health problems with a significant financial burden on the patient and on the healthcare system. This study was conducted to assess the 3-month and 1-year mortality rates of patients with operated hip fractures and to determine the influence of predictors of mortality.

Methods

In this prospective cross-sectional study, all admitted patients aged more than 50 years with hip fracture at Chamran Hospital from January 2008 to August 2013 were enrolled. The characteristic data obtained included demographic information, body mass index (BMI), smoking, any previous history of osteoporotic fracture, and comorbidities. In addition, the mechanism of fracture, fracture type, and treatment method were recorded. A follow-up with the patients was conducted at 3 months and 1 year through a telephonic interview to ask about possible mortalities. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 17.0 for Windows.

Results

A total of 1015 patients aged 50 years and older with hip fracture underwent surgery. Only 724 patients (71.3 %) completed the survey and the 1-year follow-up interview. The mean age was 75.7 ± 10.6 years. Overall, the 3-month and 1-year mortality rates were 14.5 and 22.4 %, respectively. Multivariate logistic regression analysis recognized age (OR 1.08; 95 % CI 1.05, 1.11, p < 0.001), BMI (OR 0.88; 95 % CI 0.82, 0.96, p = 0.003), and smoking (OR 1.76; 95 % CI 1.05, 2.96, p = 0.03) as major independent risk factors for mortality.

Conclusion

It is clear that modifiable factors like quitting the habit of smoking and gaining more energy with better nutrition could reduce the mortality rate if hip fracture occurs in the elderly.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hip fracture is mostly seen among old osteoporotic people, with falling down being the major cause. Notably, it is one of the most common public health problems. Hip fracture represents a significant financial burden not only on the government but also on the patient, resulting in functional impairment and compelling the patient’s family to devote time to caring for the patient. Changes in the incidence of hip fracture have been well reported in different parts of the world [1, 2]. In Iran, age-adjusted incidence rates of hip fracture were reported as 384.6 per 10,000 for men and 548.1 per 100,000 for women in 2005 [3]. During 2008–2010, the standardized age-related incidence was 329.6 per 100,000 in men and 1589.7 per 100,000 in women. This is expected to increase as a result of demographic aging [4].

Despite improvements in medical and surgical techniques, and the adoption of healthier lifestyles, risk of mortality and morbidity in patients with hip fracture is high, especially in an elderly population with several medical comorbidities [5–12]. In developed countries, multiple studies have clarified the incidence rate of mortality and its associated factors following hip fractures in the elderly. The highest mortality risk occurred during the first year following surgery, with a greater risk for men. The 1-year mortality rate reported ranged from 27.8 to 40.5 % in men and from 15.8 to 23.3 % in women [12–16]. Determining the mortality rate after hip fracture and its risk factors is crucial for public health policy and early intervention, but research on risk-associated mortality is scarce in our region. So, this study was conducted to assess 3-month and 1-year mortality rates among elderly patients with operated hip fractures and to determine the influence of predictors of mortality, including demographic and other variables.

Patients and methods

Setting and patients

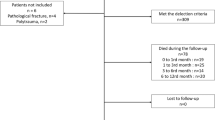

After approval of the study by the ethics committee of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, all consecutively admitted patients aged more than 50 years with hip fracture at Chamran University Hospital—the main orthopedic center in the south of Iran —from January 2008 to August 2013 were prospectively enrolled in this study. Exclusion criteria were patients with pathologic fractures, hip fracture dislocations, non-surgically treated cases, patients who died within the first day of admission, and patients who did not sign the written consent form to participate in the assessment.

Characteristic data were obtained on the patient’s arrival by filling the questionnaire. The data included demographic information, body mass index (BMI), smoking, any previous history of osteoporotic fracture, and comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus and ischemic heart disease. In addition, the mechanism of fracture, either falling down or an accident, was particularly documented. Fracture side, fracture type (i.e., femoral neck fracture, intertrochanteric fracture, and subtrochanteric fracture), and treatment method (i.e., hip arthroplasty, and reduction and fixation) were recorded through reviewing the operation notes of the patients.

Mortality assessment

A follow-up was conducted with the patients at 3 months and 1 year using telephonic interviews to ask about possible mortalities. Hence, we calculated the mortality rate at 3 months and 1 year following surgery. Possible correlations between mortality and prognostic factors—including age, gender, and fracture risk factors, such as BMI, history of pervious osteoporotic fracture, smoking, and medical comorbidities—were evaluated. Moreover, the mechanism of fracture, type of fracture, method of surgery, and length of hospital stay (defined as number of days from admission to surgery plus days from surgery to discharge) have been considered as the probable risk factors for mortality following hip fracture surgery.

Data analysis

Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD, and categorical variables and ranges were stated as absolute numbers or percentages. Chi-square tests or Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare differences in categorical variables, and Student’s t tests were used for continuous variables. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify independent predictive causal factors for mortality after surgically treated hip fractures. In addition, adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were calculated using logistic regression. Variables achieving statistical significance in the univariate analysis were considered for multivariate analysis. ORs with 95 % confidence intervals (CIs) are presented for each studied variable. Differences were considered significant at the 5 % level. All P-values reported were two-sided. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS software version 17.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

During the study period, a total of 1015 patients aged 50 years and older with hip fracture underwent surgery. Only 724 patients (71.3 %) completed the survey with a 1-year follow-up interview. Of these, 318 were male and 406 were female. The mean age was 75.7 ± 10.6 years. The mean length of hospital stay was 7.1 ± 2.6 days (injury to surgery interval: 3.4 ± 2.2 days; surgery to discharge interval: 3.7 ± 1.5 days). Falling down was the cause of 651 (89.9 %) hip fractures. Intertrochanteric fracture was the most common type of hip fracture (72.2 %), followed by femoral neck fracture and subtrochanteric fracture. Reduction and internal fixation was the most commonly used surgical management of hip fractures in studied patients (91.6 %). More than half of the patients had one or more comorbidities. About a third of the cases (239) had previous history of osteoporotic fracture.

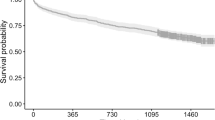

Overall, the 3-month and 1-year mortality rates were 14.5 and 22.4 %, respectively. Comparisons of baseline clinical and demographic characteristics of patients with hip fractures according to mortality status are given in Table 1. In both the 3-month and 1-year follow-ups, the mean age of the deceased patients was higher than that of the surviving patients (74.6 vs. 82.2 years; p < 0.001, 74 vs. 81.8 years; p < 0.001). BMI was lower in deceased patients, with a significant difference in the 3-month and 1-year follow-ups. A Chi-square test demonstrated a significant association between smoking (p < 0.001; p = 0.002), previous history of osteoporotic fracture (p = 0.001; p = 0.03), and mechanism of fractures (p = 0.02; p = 0.001) with a risk of mortality in both timeframes.

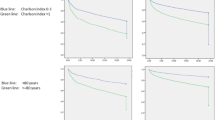

The results of multivariate logistic regression analysis to identify significant prognostic factors for mortality following hip fracture surgeries in the elderly are presented in Table 2. At 3 months following surgery, multivariate logistic regression analysis recognized age (OR 1.08; 95 % CI 1.05, 1.11, p < 0.001), BMI (OR 0.88; 95 % CI 0.82, 0.96, p = 0.003), and smoking (OR 1.76; 95 % CI 1.05, 2.96, p = 0.03) as major independent risk factors for mortality. Every year’s increase in age (odds ratio 1.08) could result in an 8 % higher risk of death, each unit of increase in BMI may result in a 10 % lower chance of death, and smoking increased the odds of mortality by 76 and 46 % in the 3-month and 1-year follow-up periods. History of previous fractures and the mechanism of fracture failed to achieve significance, based on consideration of the OR, in either primary or secondary analysis. In addition, multivariate analysis indicated that falling down was an independent predictive factor in the 1-year follow-up (OR 0.36; 95 % CI 0.14, 0.95, p = 0.04).

Discussion

The mortality rates following hip fracture surgery in our study (14.5 % at 3 months and 22.4 % at 1 year) are similar to previous studies in developed countries, which presented an increased rate of death ranging from 13 to 19 % at 3 months to 19–37 % at 1 year [17–21].

The demographic and fracture characteristics of the patients were examined as prognostic factors of mortality. In univariate analyses, age, BMI, smoking, previous history of fracture, and mechanism of fracture have significant associations with mortality. It appears that motor vehicle accidents were the cause more often in younger patients while falling down was usually seen in older persons; hence, more death in cases after falling down is the result of age and not the mechanism of injury.

Multivariate logistic regression analyses confirmed age, BMI, and smoking to be the independent factors that could significantly increase the risk of mortality. In a meta-analysis study, it was stated that age is a significant indicator for mortality following hip fracture surgery, with the risk of dying being about 70 % less in people below 85 years of age [22].

BMI is the most usual anthropometric assessment of nutritional status in old people [23]. High BMI in elderly patients shows the capability of achieving and storing energy. So, patients with higher BMI could provide the energy required for the surgery and the healing process of the fracture. Obesity, with a BMI of more than 26 in elderly patients with hip fracture, could increase the 1-year survival rate by about 2.6 [23]. About 58 % undernourishment among community-dwelling older persons admitted for hip fracture in hospitals has been reported in the literature [24]. The higher risk of death in underweight and malnourished patients is clearly explained by others [25, 26].

That smoking is a significant risk factor for death after hip fractures has been confirmed by several articles with a hazard ratio of 2.5 [27, 28].

Surprisingly, length of hospital stay and time from admission to surgery as well as type of fracture and treatment did not result in increased risk of death after surgically treated hip fractures. This is in contrast to previous studies [22, 29]; nevertheless, no correlation between delayed surgery and postoperative mortality (p > 0.05) has been reported by Williams and Jester [30]. Moreover, we could not find any relationship between the male gender and risk of mortality (p = 0.41 at 3 months, p = 0.61 at 1 year). Although another study from the west of Iran described loss of significant correlation between old male patients with hip fracture and increased risk of mortality [31], others from outside of Iran explained an increased risk of dying in male patients compared with female cases within the first year following surgery [17, 32].

In our study, the following limitations should be considered: First, time of death has been reported by family members. Second, the study was performed in the main referral center of orthopedic surgery in the south of Iran ; hence, our results could not be generalized to the entire Iranian in an elderly population. Third, approximately 30 % of patients have not completed the survey after 1 year. Fourth, details of comorbidities were sought from the patients and their family members; hence, a loss of relationship between the comorbidities and increased chance of death could not be definitely concluded.

In conclusion, decreased BMI, increased age, and smoking are the major predictors of mortality after surgery of hip fracture in the elderly population. It is clear that modifiable factors like quitting the smoking habit and gaining more energy with better nutrition could reduce the mortality rate if hip fracture occurs in the elderly.

References

Søgaard AJ, Holvik K, Meyer HE, Tell GS, Gjesdal CG, Emaus N, et al. (2016) Continued decline in hip fracture incidence in Norway: a NOREPOS study. Osteoporos Int 27(7):2217–2222

Briot K, Maravic M, Roux C (2015) Changes in number and incidence of hip fractures over 12 years in France. Bone 81:131–137. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2015.07.009

Soveid M, Serati AR, Masoompoor M (2005) Incidence of hip fracture in Shiraz, Iran. Osteoporos Int 16(11):1412–1416

Maharlouei N, Khodayari M, Forouzan F, Rezaianzadeh A, Lankarani KB (2014) The incidence rate of hip fracture in Shiraz, Iran during 2008–2010. Arch Osteoporos 9:165. doi:10.1007/s11657-013-0165-9

Belmont PJ Jr, Garcia EJ, Romano D, Bader JO, Nelson KJ, Schoenfeld AJ (2014) Risk factors for complications and in-hospital mortality following hip fractures: a study using the National Trauma Data Bank. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 134(5):597–604. doi:10.1007/s00402-014-1959-y

Tarazona-Santabalbina FJ, Belenguer-Varea A, Rovira-Daudi E, Salcedo-Mahiques E, Cuesta-Peredó D, Doménech-Pascual JR et al (2012) Early interdisciplinary hospital intervention for elderly patients with hip fractures: functional outcome and mortality. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 67(6):547–556

Patel KV, Brennan KL, Brennan ML, Jupiter DC, Shar A, Davis ML (2014) Association of a modified frailty index with mortality after femoral neck fracture in patients aged 60 years and older. Clin Orthop Relat Res 472(3):1010–1017. doi:10.1007/s11999-013-3334-7

Schilling P, Goulet JA, Dougherty PJ (2011) Do higher hospital-wide nurse staffing levels reduce in-hospital mortality in elderly patients with hip fractures: a pilot study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 469(10):2932–2940. doi:10.1007/s11999-011-1917-8

Pereira SR, Puts MT, Portela MC, Sayeg MA (2010) The impact of prefracture and hip fracture characteristics on mortality in older persons in Brazil. Clin Orthop Relat Res 468(7):1869–1883. doi:10.1007/s11999-009-1147-5

Sullivan KJ, Husak LE, Altebarmakian M, Brox WT (2016) Demographic factors in hip fracture incidence and mortality rates in California, 2000–2011. J Orthop Surg Res 11(1):4. doi:10.1186/s13018-015-0332-3

Hietala P, Strandberg M, Kiviniemi T, Strandberg N, Airaksinen KE (2014) Usefulness of troponin T to predict short-term and long-term mortality in patients after hip fracture. Am J Cardiol 114(2):193–197. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.04.026

Frost SA, Nguyen ND, Black DA, Eisman JA, Nguyen TV (2011) Risk factors for in-hospital post-hip fracture mortality. Bone 49(3):553–558. doi:10.1016/j.bone.2011.06.002

Norring-Agerskov D, Laulund AS, Lauritzen JB, Duus BR, van der Mark S, Mosfeldt M et al (2013) Metaanalysis of risk factors for mortality in patients with hip fracture. Dan Med J 60(8):A4675

Ho CA, Li CY, Hsieh KS, Chen HF (2010) Factors determining the 1-year survival after operated hip fracture: a hospital-based analysis. J Orthop Sci 15(1):30–37

Pretto M, Spirig R, Kaelin R, Muri-John V, Kressig RW, Suhm N (2010) Outcomes of elderly hip fracture patients in the Swiss healthcare system: a survey prior to the implementation of DRGs and prior to the implementation of a Geriatric Fracture Centre. Swiss Med Wkly 24(140):w13086. doi:10.4414/smw.2010.13086

Holvik K, Ranhoff AH, Martinsen MI, Solheim LF (2010) Predictors of mortality in older hip fracture inpatients admitted to an orthogeriatric unit in oslo, norway. J Aging Health 22(8):1114–1131. doi:10.1177/0898264310378040

Kannegaard PN, van der Mark S, Eiken P, Abrahamsen B (2010) Excess mortality in men compared with women following a hip fracture. National analysis of comedications, comorbidity and survival. Age Ageing 39(2):203–209. doi:10.1093/ageing/afp221

Brox WT, Chan PH, Cafri G, Inacio MC (2016) Similar mortality with general or regional anesthesia in elderly hip fracture patients. Acta Orthop 87(2):152–157

da Costa JA, Ribeiro A, Bogas M, Costa L, Varino C, Lucas R et al (2009) Mortality and functional impairment after hip fracture—a prospective study in a Portuguese population. Acta Reumatol Port 34(4):618–626

Tsuboi M, Hasegawa Y, Suzuki S, Wingstrand H, Thorngren KG (2007) Mortality and mobility after hip fracture in Japan: a ten-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 89(4):461–466

Seyedi HR, Mahdian M, Khosravi G, Bidgoli MS, Mousavi SG, Razavizadeh MR et al (2015) Prediction of mortality in hip fracture patients: role of routine blood tests. Arch Bone Jt Surg 3(1):51–55

Smith T, Pelpola K, Ball M, Ong A, Myint PK (2014) Pre-operative indicators for mortality following hip fracture surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing 43(4):464–471. doi:10.1093/ageing/afu065

Flodin L, Laurin A, Lökk J, Cederholm T, Hedström M (2016) Increased 1-year survival and discharge to independent living in overweight hip fracture patients. Acta Orthop 87(2):146–151

Fiatarone Singh MA, Singh NA, Hansen RD, Finnegan TP, Allen BJ, Diamond TH et al (2009) Methodology and baseline characteristics for the Sarcopenia and Hip Fracture study: a 5-year prospective study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 64(5):568–574. doi:10.1093/gerona/glp002

Juliebø V, Krogseth M, Skovlund E, Engedal K, Wyller TB (2010) Medical treatment predicts mortality after hip fracture. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 65(4):442–449. doi:10.1093/gerona/glp199

Bell JJ, Pulle RC, Crouch AM, Kuys SS, Ferrier RL, Whitehouse SL (2016) Impact of malnutrition on 12-month mortality following acute hip fracture. ANZ J Surg 86(3):157–161. doi:10.1111/ans.13429

Hung LW, Tseng WJ, Huang GS, Lin J (2014) High short-term and long-term excess mortality in geriatric patients after hip fracture: a prospective cohort study in Taiwan. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 15:151. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-15-151

Heyes GJ, Tucker A, Marley D, Foster A (2015) Predictors for 1-year mortality following hip fracture: a retrospective review of 465 consecutive patients. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. doi:10.1007/s00068-015-0556-2 [Epub ahead of print]

Nikkel LE, Kates SL, Schreck M, Maceroli M, Mahmood B, Elfar JC (2015) Length of hospital stay after hip fracture and risk of early mortality after discharge in New York State: retrospective cohort study. BMJ 351:h6246. doi:10.1136/bmj.h6246

Williams A, Jester R (2005) Delayed surgical fixation of fractured hips in older people: impact on mortality. J Adv Nurs 52(1):63–69

Valizadeh M, Mazloomzadeh S, Golmohammadi S, Larijani B (2012) Mortality after low trauma hip fracture: a prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 13:143. doi:10.1186/1471-2474-13-143

Man LP, Ho AW, Wong SH (2016) Excess mortality for operated geriatric hip fracture in Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J 22(1):6–10. doi:10.12809/hkmj154568

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Vice-Chancellor for Research at Shiraz University of Medical Sciences. The authors would like to thank Mrs. Zeinab Kargar for collecting the data and also Dr. Asmarian for analyzing them.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Vosoughi, A.R., Emami, M.J., Pourabbas, B. et al. Factors increasing mortality of the elderly following hip fracture surgery: role of body mass index, age, and smoking. Musculoskelet Surg 101, 25–29 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12306-016-0432-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12306-016-0432-1