Abstract

Central neurocytoma is generally considered to be a benign tumor and the literature suggests that a cure may be attained by surgery ± adjuvant focal irradiation. However, there is a need for change in the therapeutic strategy for the subgroup of patients with aggressive central neurocytoma. An example case is presented and the literature on central neurocytoma cases with malignant features and dissemination via the cerebrospinal fluid is reviewed and the radiotherapeutic strategies available for central neurocytoma treatment is discussed. Nineteen cases including the present report with a malignant course and cerebrospinal fluid dissemination have been described to date, most of them involving an elevated MIB-1 labeling index. Our case exhibited atypical central neurocytoma with an initially elevated MIB-1 labeling index (25–30 %). The primary treatment included surgery and focal radiotherapy. Three years later the disease had disseminated throughout the craniospinal axis. A good tumor response and symptom relief were achieved with repeated radiation and temozolomide chemotherapy. Central neurocytoma with an initially high proliferation activity has a high tendency to spread via the cerebrospinal fluid. The chemo- and radiosensitivity of the tumor suggest a more aggressive adjuvant therapy approach. Cases with a potential for malignant transformation should be identified and treated appropriately, including irradiation of the entire neuroaxis and adjuvant chemotherapy may be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Detection of the malignant transformation of central neurocytoma (CN) at the time of the diagnosis is a rare feature of this basically benign tumor, which is mainly associated with a favorable outcome. Before the entity of neurocytoma was described by Hassoun et al. [1] in 1982 such tumors were referred to intraventricular ependymomas or sometimes oligodendrogliomas. The latest WHO classification categorizes CN as a grade II tumor [2–5]. Following the cellular origin, it has been established that neurocytoma has the properties of bipotential precursor cells, which can exhibit both glial and neuronal differentiation [6]. Immunohistochemical studies have identified markers of neuronal differentiation such as neuron-specific enolase and synaptophysin [7, 8], this staining confirming the diagnosis of neurocytoma. This tumor entity, which accounts for only 0.1–0.5 % of all brain neoplasms [9–12], displays a slow and benign clinical course with a low recurrence rate and a low tendency to spread. Most neurocytomas arise from the septum pellucidum, fornix or walls of the lateral ventricles, with relatively frequent extension to the lateral and third ventricles, often causing obstructive hydrocephalus in relation to the foramen of Monro. The lesions are mainly located in the midline supratentorially, and more commonly on the right side [13]. The occurrence of such tumors outside the cerebral ventricular system is infrequent [14], reported first in 1989 [15], and these lesions have been termed extraventricular neurocytomas. CN develops mainly in young adults around the third decade of life [10, 12] (ranging from childhood to 70 years). It has been detected with higher incidence in Asian populations, than among Caucasians. The majority of the case reports and accounts of small series originate from India [16–20], China [21–23], Japan [7, 24–29], and Korea [11, 30–34]. Gross total resection (GTR) ensures high progression-free and overall survival rates without recurrence [5], but rare cases of more aggressive behavior with dissemination in the craniospinal axis have been reported. On the basis of the histological findings, such as nuclear atypia, anaplasia, vascular endothelial proliferation, focal necrosis, and/or an increased mitotic index [2, 5, 35–37] a subgroup of this tumor entity is defined as atypical neurocytoma. An MIB-1 labeling index (MIB-1 LI) of ≥2 % or >3 % has been claimed to be associated with a significantly poorer survival and to correlate with a higher risk of relapse; moreover an MIB-1 LI of >4 % correlates significantly with an unfavorable clinical course [38, 39]. Such a high proliferation index is quite uncommon and the detection of malignant transformation at the time of the diagnosis is extremely rare. Adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) has been stated to be beneficial for patients with such atypical neurocytoma and incomplete resection. In general, irradiation of the whole craniospinal space is not recommended, but evidence has recently been accumulating of tumors that disseminate in the central nervous system.

Presentation of Our Example Case

In February 2007, a 40-year-old man presented to our hospital with a history of a few weeks of visual impairment, and diplopia. MRI revealed a mass at the bottom and in the posterior third of the third ventricle, which constricted the aqueduct and caused an occlusive hydrocephalus. Via an endoscopic ventriculostomy, aspiration biopsy was performed. The cytopathological analysis demonstrated a cell-dense tissue, with mild cellular atypia reminiscent of ependymal cells. A focal rosette structure was observed, but there was no glomeruloid vessel proliferation, necrosis, palisade necrosis or mitosis. At that time a WHO grade II ependymoma was diagnosed. One week later, GTR of the tumor was carried out through an occipital osteoplastic craniotomy. In the early postoperative period the patient was somnolent and displayed slowness of movements. Because of the abnormality of the CSF circulation, a ventricular drain was inserted. Several febrile episodes recurred and lumbar punctures demonstrated an elevated leukocyte count in the CSF; parenteral antibiotic was therefore administered, which resulted in an improvement of the condition of the patient and the circulation of the CSF normalized. The patient still presented diplopia, but no other neurological symptoms.

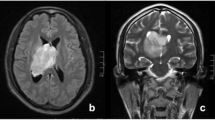

Cytopathological analysis demonstrated a cell-dense, well-vascularized tumor tissue. The nuclei were normal, and the cytoplasm was moderately granulated. The cells were positive for synaptophysin and negative for GFAP. The MIB-1 LI was 25–30 %. These findings corresponded to a diagnosis of WHO grade II CN (Figs. 1, 2 and 3).

The patient was prepared for whole-neuraxis irradiation, but the CSF was negative for tumor cells and there was no suggestion in this respect in the literature overview, so he finally participated in adjuvant, local RT by the 3D conformal technique with a cummulative dose of 60 Gy in daily fractions of 1.8 Gy to the primary tumor bed.

Until 2010 the patient was symptom-free, but in March of that year there were signs of muscle weakness, an increase in the deep tendon reflexes, moderate numbness in the left arm and paresthesia in the lateral proximal region (headzone C 7–8). A spinal MRI showed numerous small cervical, two thoracal and several lumbar, mostly extramedullary manifestations (Fig. 4.). Reoperation was performed and all tumor-seeming tissue was removed from the thoracal IV-VI region through hemilaminectomia and dura mater opening. The postoperative period was uneventful. Cytopathological analysis indicated a hypercellular, undifferentiated tumor tissue. Moderate cell atypia and several mitoses were observed. Immunohistological analysis demonstrated GFAP and CK-KL1 negativity, synaptophysin positivity, a highly positive MIB-1 LI of >40 %, NF: +/−, and CD99: +/−. This was characteristic of malignantly transformed, disseminated CN of WHO grade III. Postoperative, conformal irradiation of the whole spinal cord was performed in a total dose of 36 Gy in conventional fractionation, and a 10 Gy boost was delivered to the tumor bed in the thoracal IV–VI region.

In November 2010, the patient presented with severe pain in the shoulders, numbness in both arms and hands and moderate muscle weakness in the right arm. CT showed moderate tumor progression in the cervical spinal cord. At that time the patient underwent simultaneous chemoradiotherapy with 200 mg/m2 temozolomide five times per week in 28-days cycles and received an irradiation dose of 22.5 Gy in 1.5 Gy daily fractions to the cervical spinal region. He was then placed on 200 mg/m2 temozolomide monotherapy. He remained stable and symptom-free, and the repeated MRI examinations showed mild tumor regression until November 2011, when the follow-up MRI detected tumor recurrence in the left frontal lobe, in the occipital lobes on both sides, and in the left cerebellum (Figs. 5 and 6). Reirradiation was carried out to the whole brain in a cumulative dose of 27 Gy in 1.8 Gy daily fractions, with initial tumor bed avoidance, and an additional boost dose of 8 Gy in 1 Gy daily fractions to the cerebral and cerebellar manifestations. For a few months the good condition of the patient persisted, but a slow deterioration of his physical performance started in February 2012 and he died in April 2012, 62 months after the initial diagnosis and operation. Permission for autopsy was not granted by the family.

Discussion

There has so far been no randomized clinical trial involving CN because of the rarity of this tumor. Only case reports, retrospective case studies and meta-analyses of small numbers of patients are available with therapeutic recommendations. GTR provides the best local control and survival rates. Postoperative irradiation is beneficial after STR and for atypical CN cases [2, 40]. Peak et al. [41] reported on 6 cases of CN (no allusion to the typ of CN), who underwent postoperative RT after GTR (3 cases) or STR (3 cases). The patients were treated with Co-60 gamma-irradiation. The median total dose to the primary tumor was 54 Gy. At the last follow-up, the KPS scores had deteriorated, due to white-matter demyelination. This report demonstrates that RT can control residual CN effectively and is beneficial, but more sophisticated irradiation techniques should be used to avoid serious late sequelae.

There have been several reports on small numbers of CN cases treated with conformal, adjuvant RT. Kim et al. [31] concluded that better local control rates can be achieved with RT. Schild et al. [42] and Rades et al. [43] retrospectively analyzed the available CN small-series literature reports and archives from their institution (32 and 85 cases, respectively). Those authors concluded that postoperative RT should be considered only in cases of STR and should involve only the initial tumor bed, because CNs neither infiltrate the brain parenchyma nor metastasize.

Rades et al. [44] reviewed and retrospectively analyzed 89 published incompletely resected cases of CN and recommended a guideline for the local RT: the target volume should include the preoperative tumor volume and 2 cm safety margin and should be irradiated with a total dose of 54–62.2 Gy. Leenstra et al. [2] likewise concluded that postoperative RT significantly improved the local control rate. They confirmed a nonsignificant tendency toward a better local control rate at 5 years when the MIB-1 LI was ≤2 %. This demonstrated that the MIB-1 LI could be used as a predictive marker of the clinical outcome. Several reports have been published on the usage and effectiveness of the gamma knife and stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS) for typical CN [34, 45].

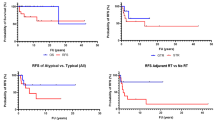

In opposite to the localised benign CN, 19 cases including the present report have been described in the literature with unfavorable clinical course and rapid progression: high rates of local recurrence and craniospinal dissemination prior to the diagnosis or following surgical resection (Table 1). 11 of the 13 patients for whom data were accessible had an initial MIB-1 LI >2 %. The MIB-1 LI was not significantly higher among the patients who died because of disease progression. For the group of patients in whom the first tumor recurrence or dissemination occurred within 12 months, a higher mean MIB-1 LI was observed (mean 17.82 %, range 4.4–37.3 %). There was a nonsignificant tendency toward an unfavorable clinical course if the MIB-1 LI was initially elevated. The same phenomenon was observed for the patients who developed spinal metastases, who exhibited an initial mean MIB-1 LI of 13.4 %.

There were no differences in age and gender distribution and in localisation between the typical and atypical CN. Malignant CN arises mainly from the septum pellucidum (n = 4), fornix or walls of the ventricles (lateral (n = 8), third and (n = 1), fourth ventricles (n = 1)) with relatively frequent spreading to the surrounding structures: to the thalamus (n = 5), the frontal lobe (n = 1) and the ventricles(n = 4) and in one case the tumor was already multifocally spread. Due to the diffuse growth toward the adjacent structures GTR could be carried out in only 3/18 cases, 13 patients underwent STR, and 2 biopsy only. Reoperation was carried out in 4 cases.

16/18 patients received adjuvant treatment, i.e. RT ± chemotherapy. A huge variety of RT techniques (SRS = 3, conformal RT = 12), doses (25–66 Gy) and cytotoxic agents and combination were used (etoposide, carboplatin, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, vincristine, cytarabine, ifosfamide, imatinib, temozolomide, toptecan, thioTEPA, and nimustine). Four patients received only chemotherapy and two patients did not get any postoperative treatment. The whole craniospinal axis was treated only in the cases with proven manifestation in the spinal cord (n = 2). In case 8 [51], 39.6 Gy was administered to the entire neuraxis and an additional 14.4 Gy to the thoracal spine, sequential to cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and cisplatin. In case 17 [58], the craniospinal axis was treated with 36 Gy, and a 20 Gy boost was given to the tumor bed and to the upper cervical spine. Reirradiation was carried out in 3 cases, and diverse chemotherapeutic regimes were performed for the treatment of recurrences. In our patient temozolomide resulted in good response lasting for 12 months.

The clinical outcome was available for all cases. 7 patients died because of tumor dissemination and disease progression. The estimated mean survival was 27.9 months (range 5–46). 7 patients were in a stable condition at the time of their last follow-up examination. The mean follow-up period was 32.4 month (range 7–72). 2 patients were in disease progression at their last follow-up 15 and 7 months after the first operation. 2 patients were disease-free 9 and 132 months after the first tumor removal. The estimated mean progression-free survival was 15.3 months, ranging from 2 to 36 months.

One patient had multifocal disseminated disease at the time of the diagnosis. In the other cases, recurrence was always observed. CSF spreading was detected in 16/18 cases (ventricular n = 5 on average 11 months after the first operation and spinal metastases n = 11 an average of 21.1 months (range 5–36)). One patient exhibited peritoneal dissemination through the ventriculo-peritoneal shunt 43 months after the diagnosis.

In our case, we planned irradiation of the entire neuraxis as initial therapy, but the literature review at that time led us to change our treatment strategy to focal irradiation only. Irradiation of the recurrencies resulted in a good tumor response lasting from some months to years. The clinical course of the disease proved the inappropriateness of our decision on the postoperative treatment (local irradiation only), because this review of the separately reported malignant CN cases shows high probability of spread via the CSF (89 %) and the tumor exhibits good radiosensitivity.

Conclusions

There is currently no standard accepted therapeutic option for atypical CN; a rare central nervous system malignancy. The patients are treated with a large variety of different approaches. The conclusions drawn from meta-analyses of reports on benign CN can not be applied in cases with aggressive behavior. Our systematic evaluation of the available sporadic case reports has demonstrated that the cases with potential malignant transformation should be differentiated, and treated accordingly. Apart from the nuclear atypia, anaplasia, vascular endothelial proliferation, focal necrosis, and/or an increased mitotic index, correct evaluation of the MIB-1 LI can help in the identification of these patients. In that cases after the largest possible surgical removal, adjuvant neuroaxis irradiation should be considered.

References

Hassoun J, Gambareli D, Grisoli F, Pellet W, Salamon G, Pellisier JF, Toga M (1982) Central neurocytoma—an electron-microscopic study of 2 cases. Acta Neuropathol 56:151–156

Leenstra JL, Rodriguez FJ, Frechette CM, Giannini C, Stafford SL, Pollock BE, Schild SE, Scheithauer BW, Jenkins RB, Buckner JC, Brown PD (2007) Central neurocytoma: management recommendations based on a 35-year experience. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 67:1145–1154

Rades D, Fehlauer F, Lamszus K, Schild SE, Hagel C, Westphal M, Alberti W (2005) Well-differentiated neurocytoma: what is the best available treatment? Neuro-Oncol 7:77–83

Schmidt MH, Gottfried ON, von Koch CS, Chang SM, McDermott MW (2004) Central neurocytoma: a review. J Neurooncol 66:377–384

Vasiljevic A, Francois P, Loundou A, Fevre-Montange M, Jouvet A, Roche PH, Figarella-Branger D (2012) Prognostic factors in central neurocytomas: a multicenter study of 71 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 36:220–227

Kane AJ, Sughrue ME, Rutkowski MJ, Tihan T, Parsa AT (2011) The molecular pathology of central neurocytomas. J Clin Neurosci 18:1–6

Kubota T, Hayashi M, Kawano H, Kabuto M, Sato K, Ishise J, Kawamoto K, Shirataki K, Iizuka H, Tsunoda S, Katsuyama J (1991) Central neurocytoma - immunohistochemical and ultrastructural-study. Acta Neuropathol 81:418–427

Von Deimling A, Janzer R, Kleihues P, Wiestler OD (1990) Patterns of differentiation in central neurocytoma—an immunohistochemical study of 11 biopsies. Acta Neuropathol 79:473–479

Coca S, Moreno M, Martos JA, Rodriguez J, Barcena A, Vaquero J (1994) Neurocytoma of spinal-cord. Acta Neuropathol 87:537–540

Hassoun J, Soylemezoglu F, Gambarelli D, Figarella-Branger D, Von Ammon K, Kleihues P (1993) Central neurocytoma—a synopsis of clinical and histological features. Brain Pathol 3:297–306

Kim DG, Chi JG, Parks SH, Chang KH, Lee SH, Jung HW, Kim HJ, Cho BK, Choi KS, Han DH (1992) Intraventricular neurocytoma - clinicopathological analysis of 7 cases. J Neurosurg 76:759–765

Figarella-Branger D, Söylemezoglu F, Kleihues P, Hassoun J, Cavenee WK (2000) Central neurocytoma. In: Kleihues P (ed) World health classification of tumours. Tumours of the nervous system. Pathology and genetics. IARC, Lyon, pp 107–109

Sharma MC, Deb P, Sharma S, Sarkar C (2006) Neurocytoma: a comprehensive review. Neurosurg Rev 29:270–285

Giangaspero F, Cenacchi G, Losi L, Cerasoli S, Bisceglia M, Burger PC (1997) Extraventricular neoplasms with neurocytoma features—a clinicopathological study of 11 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 21:206–212

Ferreol E, Sawaya R, de Courten-Myers GM (1989) Primary cerebral neuro-blastoma (neurocytoma) in adults. J Neurooncol 7:121–128

Kulkarni V, Rajshekhar V, Haran RP, Chandi SM (2002) Long-term outcome in patients with central neurocytoma following stereotactic biopsy and radiation therapy. Br J Neurosurg 16:126–132

Sharma MC, Rathore A, Karak AK, Sarkar C (1998) A study of proliferative markers in central neurocytoma. Pathology 30:355–359

Sharma MC, Sarkar C, Karak AK, Gaikwad S, Mahapatra AK, Mehta VS (1999) Intraventricular neurocytoma: a clinicopathological study of 20 cases with review of the literature. J Clin Neurosci 6:319–323

Sharma S, Sarkar C, Gaikwad S, Suri A, Sharma MC (2005) Primary neurocytoma of the spinal cord: a case report and review of literature. J Neurooncol 74:47–52

Jaiswal S, Vij M, Rajput D, Mehrotra A, Jaiswal AK, Srivastava AK, Behari S, Krishnani N (2011) A clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and neuroradiological study of eight patients with central neurocytoma. J Clin Neurosci 18:334–339

Chen CM, Chen KH, Jung SM, Hsu HC, Wang CM (2008) Central neurocytoma: 9 case series and review. Surg Neurol 70:204–209

Chen H, Zhou R, Liu J, Tang J (2012) Central neurocytoma. J Clin Neurosci 19:849–853

Chen CL, Shen CC, Wang J, Lu CH, Lee HT (2008) Central neurocytoma: a clinical, radiological and pathological study of nine cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 110:129–136

Ishiuchi S, Nakazato Y, Iino M, Ozawa S, Tamura M, Ohye C (1998) In vitro neuronal and glial production and differentiation of human central neurocytoma cells. J Neurosci Res 51:526–535

Ishiuchi S, Tamura M (1997) Central neurocytoma: an immunohistochemical, ultrastructural and cell culture study. Acta Neuropathol 94:425–435

Kawashima M, Suzuki SO, Doh-ura K, Iwaki T (2000) alpha-Synuclein is expressed in a variety of brain tumors showing neuronal differentiation. Acta Neuropathol 99:154–160

Nakagawa K, Aoki Y, Sakata K, Sasaki Y, Matsutani M, Akanuma A (1993) Radiation-therapy of well-differentiated neuroblastoma and central neurocytoma. Cancer 72:1350–1355

Namiki J, Nakatsukasa M, Murase I, Yamazaki K (1998) Central neurocytoma presenting with intratumoral hemorrhage 15 years after initial treatment by partial removal and irradiation—case report. Neurol Med 38:278–282

Nishio S, Takeshita I, Kaneko Y, Fukui M (1992) Cerebral neurocytoma—a new subset of benign neuronal tumors of the cerebrum. Cancer 70:529–537

Kim DG, Kim JS, Chi JG, Park SH, Jung HW, Choi KS, Han DH (1996) Central neurocytoma: proliferative potential and biological behavior. J Neurosurg 84:742–747

Kim DG, Paek SH, Kim IH, Chi JG, Jung HW, Han DH, Choi KS, Cho BK (1997) Central neurocytoma—the role of radiation therapy and long term outcome. Cancer 79:1995–2002

Kim DH, Suh YL (1997) Pseudopapillary neurocytoma of temporal lobe with glial differentiation. Acta Neuropathol 94:187–191

Kim DG, Choe WJ, Chang KH, Song IC, Han MH, Jung HW, Cho BK (2000) In vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy of central neurocytomas. Neurosurgery 46:329–333

Kim CY, Paek SH, Jeong SS, Chung HT, Han JH, Park CK, Jung HW, Kim DG (2007) Gamma knife radiosurgery for central neurocytoma—primary and secondary treatment. Cancer 110:2276–2284

Rades D, Schild SE (2006) Treatment recommendations for the various subgroups of neurocytomas. J Neurooncol 77:305–309

Soylemezoglu F, Scheithauer BW, Esteve J, Kleihues P (1997) Atypical central neurocytoma. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 56:551–556

Mackenzie IRA (1999) Central neurocytoma—histologic atypia, proliferation potential, and clinical outcome. Cancer 85:1606–1610

Lenzi J, Salvati M, Raco A, Frati A, Piccirilli M, Delfini R (2006) Central neurocytoma: a novel appraisal of a polymorphic pathology—our experience and a review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev 29:286–292

Rades D, Schild SE, Fehlauer F (2004) Prognostic value of the MIB-1 labeling index for central neurocytomas. Neurology 62:987–989

Lee J, Chang SM, McDermott MW, Parsa AT (2003) Intraventricular neurocytomas. Neurosurg Clin N Am 14:483–508

Paek SH, Han JH, Kim JW, Park CK, Jung HW, Park SH, Kim IH, Kim DG (2008) Long-term outcome of conventional radiation therapy for central neurocytoma. J Neurooncol 90:25–30

Schild SE, Scheithauer BW, Haddock MG, Schiff D, Burger PC, Wong WW, Lyons MK (1997) Central neurocytomas. Cancer 79:790–795

Rades D, Fehlauer F, Schild SE (2004) Treatment of atypical neurocytomas. Cancer 100:814–817

Rades D, Schild SE, Ikezaki K, Fehlauer F (2003) Defining the optimal dose of radiation after incomplete resection of central neurocytomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 55:373–377

Rades D, Schild SE (2006) Value of postoperative stereotactic radiosurgery and conventional radiotherapy for incompletely resected typical neurocytomas. Cancer 106:1140–1143

Neto MC, Ramina R, de Meneses MS, Arruda WO, Milano JB (2003) Peritioneal dissemination from central neurocytoma—case report. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 61:1030–1034

Stapleton CJ, Walcott BP, Kahle KT, Codd PJ, Nahed BV, Chen L, Robison NJ, Delalle I, Goumnerova LC, Jackson EM (2012) Diffuse central neurocytoma with craniospinal dissemination. J Clin Neurosci 19:163–166

Amini E, Roffidal T, Lee A, Fuller GN, Mahajan A, Ketonen L, Kobrinsky N, Cairo MS, Wells RJ, Wolff JEA (2008) Central neurocytoma responsive to topotecan, ifosfamide, carboplatin. Pediatr Blood Cancer 51:137–140

Elek G, Slowik F, Eross L, Tóth S, Szabó Z, Bálint K (1999) Central neurocytoma with malignant course: neuronal and glial differentiation and craniospinal dissemination. Pathol Oncol Res 5:155–159

Eng DY, DeMonte F, Ginsberg L, Fuller GN, Jaeckle K (1997) Craniospinal dissemination of central neurocytoma—report of two cases. J Neurosurg 86:547–552

Brandes AA, Amista P, Gardiman M, Volpin L, Danieli D, Guglielmi B, Carollo C, Pinna G, Turazzi S, Monfardini S (2000) Chemotherapy in patients with recurrent and progressive central neurocytoma. Cancer 88:169–174

Ando K, Ishikura R, Morikawa T, Nakao N, Ikeda J, Matsumoto T, Arita N (2002) Central neurocytoma with craniospinal dissemination. Magn Reson Med Sci 1:179–182

Tran H, Medina-Flores R, Cerilli LA, Phelps J, Lee FC, Wong G, Turner P (2010) Primary disseminated central neurocytoma: cytological and MRI evidence of tumor spread prior to surgery. J Neurooncol 100:291–298

Ogawa Y, Sugawara T, Seki H, Sakuma T (2006) Central neurocytomas with MIB-1 labeling index over 10% showing rapid tumor growth and dissemination. J Neurooncol 79:211–216

Takao H, Nakagawa K, Ohtomo K (2003) Central neurocytoma with craniospinal dissemination. J Neurooncol 61:255–259

Amagasa M, Yuda F, Sat S, Kojima H (2008) Central neurocytoma with remarkably large rosette formation and rapid malignant progression: a clinicopathological follow-up study with autopsy report. Clin Neuropathol 27:252–257

Tomura N, Hirano H, Watanabe O, Watarai J, Itoh Y, Mineura K, Kowada M (1997) Central neurocytoma with clinically malignant behavior. Am J Neuroradiol 18:1175–1178

Cook DJ, Christie SD, Macaulay RJB, Rheaume DE, Holness RO (2004) Fourth ventricular neurocytoma: case report and review of the literature. Can J Neurol Sci 31:558–564

Bertalanffy A, Roessler K, Koperek O, Gelpi E, Prayer D, Knosp E (2005) Recurrent central neurocytomas. Cancer 104:135–142

Acknowledgments

The research project was supported by the OTKA fund No. 75833. The OTKA is an official grant provided by the Hungarian government via the Hungarian Scientific Academy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mozes, P., Szanto, E., Tiszlavicz, L. et al. Clinical Course of Central Neurocytoma with Malignant Transformation—An Indication for Craniospinal Irradiation. Pathol. Oncol. Res. 20, 319–325 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-013-9697-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12253-013-9697-y