Abstract

Loneliness is an unpleasant experience of lacking desired interpersonal relationships. Abundant evidence has clarified the negative outcomes of loneliness, such as anxiety, even suicidal behaviors. However, relatively few is known about the internal buffering elements for loneliness, especially in adolescents. The current research aimed to investigate the relationship between self-compassion and adolescents’ loneliness, as well as the mediating roles of fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety in this relationship. A total of 871 Chinese adolescents completed a set of questionnaires, including the measures of loneliness, self-compassion, social anxiety and the fear of negative evaluation. We tested the proposed serial mediation model and the results suggested that self-compassion was negatively associated with loneliness, and social anxiety served as a mediator in the relationship. Besides, we found that the fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety serially mediated the negative association. Specifically, self-compassionate adolescents reported less fear of negative evaluation, which resulted in decreased social anxiety symptoms. In turn, the decreased social anxiety was linked to reduced feelings of loneliness. The present study sheds lights on the mediating effects of fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety in the relationship between self-compassion and loneliness. The theoretical and practical implications, as well as the limitations of the present study, are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Adolescence is a challenging period for individuals (Collins and Steinberg 2007). Due to the dramatic changes in cognition, physiology and sociopsychology, adolescents are at high risks of mental health problems, such as the profound sense of loneliness (Hawthorne 2008). Loneliness refers to an unpleasant experience of lacking desired interpersonal relationships, and has become a growing concern for adolescents (Mahon et al. 2006). Since the desire of belonging is particularly salient during adolescence, chronic loneliness might have detrimental impact on both psychosocial functioning and physical development, such as increased depression, anxiety, stress, lower self-esteem, poorer perceived health, sleep problems, and even suicidal ideations and behaviors (Vanhalst et al. 2013a, b; Harris et al. 2013; Roberts et al. 1998).

Given the prevalence and the severity of maladjustment problems concerning loneliness, identifying protective factors that keep adolescents from experiencing loneliness has gained much interests. While some studies predominantly focused on exploring the environmental protective factors of loneliness (e.g., friendship quality; Nangle et al. 2003), relatively few is known about the internal buffering elements. A recent study found that self-compassion, an emotionally positive and healthy self-attitude, made unique contributions to the feelings of loneliness in university student samples, illustrating the potential protective effect of self-compassion in decreasing loneliness (Akin 2010). Nevertheless, it is not clear whether the same relation exists in adolescents and its underlying psychological mechanisms. Understanding the relationship between self-compassion and feelings of loneliness in adolescents and mechanisms behind may be very crucial for conducting health-based research, especially for preventative ones and relevant interventions for adolescents to prevent against or compensate the negative effects of loneliness. For this purpose, our current study aimed to better understand the relationship between self-compassion and loneliness in a relatively large Chinese adolescent sample, and further to reveal the potential mediating pathways underlying this association.

Self-Compassion and Loneliness

Self-compassion describes an emotionally positive self-attitude when faced with suffering, shortcomings and hardship (Neff 2003a). Specifically, self-compassion entails treating oneself with tenderness and understanding, recognizing one’s inadequacies as part of shared human experiences, and maintaining a balanced state when considering negative aspects of oneself or confronting stressful events (Neff et al. 2007). It is well-established that self-compassion robustly benefits various mental health indicators as well as overall well-being (Neff 2003a, b). Specifically, self-compassion helps generate more effective coping strategies, such as adaptive emotion-focused strategies, and thus protects individuals against negative self-feelings after experiencing great stress (Leary et al. 2007; Allen and Leary 2010). Also, research has shown that self-compassion could contribute to individuals’ social functioning. For instance, self-compassion has shown to be positively associated with extraversion, agreeableness, social connectedness, and prosocial behavior (Baker and McNulty 2011; Yang et al. 2019).

Loneliness involves the awareness of unfulfilled intimate social relationship and a deficiency in social needs (Akin 2010), while adopting a self-compassionate mindset may help cultivate healthy social connections and satisfy people’s social needs. Specifically, self-compassion aids individuals in recognizing that all humans, including self and others, are worthy to be treated kindly, since everyone might face inadequacies, stress, failures and difficulties inevitably, which helps generate a sense of connection with others and fulfill the need for relatedness (Akin 2010; Yang et al. 2019). Also, individuals with higher self-compassion report higher agreeableness (Neff et al. 2007), and are more likely to deal with interpersonal conflicts adaptively and maintain healthy interpersonal relationships (Allen and Leary 2010), which may promote social interaction and then protect against heightened feelings of loneliness. Empirically, recent studies have demonstrated that self-compassion is negatively related to the feelings of loneliness in graduate and university student samples (Akin 2010; Lyon 2015). Based on the literature above, we hypothesized that self-compassion would be negatively associated with loneliness in adolescents (H1).

The Mediation Role of Fear of Negative Evaluation and Social Anxiety between Self-Compassion and Loneliness

What mechanisms may explain the association between self-compassion and reduced loneliness? The present study aimed to explore the mediation role of social anxiety and fear of negative evaluation between self-compassion and loneliness. Social anxiety is conceptualized as the integrated feelings apprehension and worry that people would experience when they expect to behave well and obtain praise (La Greca and Lopez 1998), while the fear of negative evaluation is defined as a fear of individual’s potential and possible negative evaluation from others in a social context (Weeks et al. 2005). Although some scholars suggested that fear of negative evaluation could be included in the measurement of social anxiety (La Greca and Lopez 1998), other researchers regarded fear of negative evaluation as an independent factor from social anxiety (e.g., Leary 1983; Kocovski and Endler 2000). By definition, the fear of negative evaluation places emphasis on the fear or dread of being evaluated unfavorably in social situations, whereas social anxiety pertains to the affective reactions, mainly anxiety, to such circumstances. Fear and anxiety are two related but distinct emotions associated with different behavioral characteristics, with anxiety being the emotional byproduct of fearful cognitions (Sylvers et al. 2011). In line with this point of view, social anxiety is an emotional response of fear of evaluation in general (Carleton et al. 2007; Weeks et al. 2008b). Thus, it is reasonable and also necessary to consider fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety as separate constructs. In our study we intended to test the respective roles of these two related but distinct constructs in explaining the relationship between self-compassion and loneliness.

Social anxiety has been evidenced to be a profound predictor of loneliness during adolescence and adulthood, that is, individuals with higher levels of social anxiety demonstrated heightened feelings of loneliness (Mahon et al. 2006; Lim et al. 2016). The feeling of anxiety in social situations is a powerful motivator triggering avoidance of anxiety-provoking situation (Watson and Nesdale 2012), so that people tend to be socially withdrawn when they are about to or already feel anxious, which might generate the sense of loneliness since the need for belongingness cannot be satisfied (Liao et al. 2014).

On the other hand, self-compassion may reduce the generation of social anxiety. Self-compassion allows individuals to treat themselves with kindness, realize that others may also have bad performance in everyday social interaction, and maintain a balanced mindset dealing with social anxiety, all of which make people less anxious about manifesting themselves in an embarrassing or unfavorable manner (Blackie and Kocovski 2018). Empirical research has pointed out that individuals with higher self-compassion tend to experience lower social anxiety (Potter et al. 2014; Blackie and Kocovski 2018). In addition, Arch and his colleagues found that compared to the control group, women who accepted brief self-compassion training showed a significantly reduction in state anxiety under stressful situations, suggesting that self-compassion is a promising approach in diminishing potential negative psychological and biological effects when faced with social stress (Arch et al. 2014). Harwood and Kocovski (2017) also found that students who were asked to write self-compassionately reported lower levels of anticipatory anxiety than control group. Therefore, we hypothesized that social anxiety may mediate the relationship between self-compassion and loneliness in adolescents (H2a).

Fear of negative evaluation is becoming a prevalent and salient phenomenon during adolescence, and is associated with various maladaptive consequences, including loneliness (Jackson et al. 2002). Fear of negative evaluation is derived from past experiences and core beliefs about others, and would affect individuals’ coping abilities in daily life (Gill et al. 2018). In other words, fear of negative evaluation interferes with individual’s attempts to interact with others, which may detrimentally affect appropriate social interaction and may elevate the experience of loneliness (Jackson et al. 2002). Empirical studies have supported the arguments, showing that the fear of negative evaluation is significantly associated with loneliness in both adolescent and undergraduate samples (Jackson 2007).

Since individuals with more fear of negative evaluation would tend to feel much worse about receiving negative evaluations (Leary 1983), holding a self-compassionate mindset may offer unique benefits. Characterized by kindness and non-judgmental attitude towards oneself, self-compassion has been evidenced to buffer individuals against social threats of their failures, and engender a positive self-feeling when life goes badly (Leary et al. 2007). Hence, self-compassionate people might not be as much affected by the fear of negative evaluations from others as people with low self-compassion. In line with the reasoning, considerable studies have found that self-compassion is negatively correlated with fears of positive or negative evaluation by others (Werner et al. 2012; Weeks et al. 2008a, b). Therefore, we hypothesized that fear of negative evaluation may mediate the relationship between self-compassion and loneliness in adolescents (H2b).

What’s more, the cognitive behavioral model of social anxiety posited that individuals’ attention to the evaluation from others is one of the main causes of social anxiety (Heimberg et al. 2010; Clark and Wells 1995). That is, people who view the social world as a potentially social-evaluative situations may more frequently perceive the fear of negative evaluation from others who they interact with (Heimberg et al. 2010), and such profound feelings of fear would in turn result in social anxiety syndromes, which suggested that fear of negative evaluation may be one of the antecedents of social anxiety (Cheng et al. 2015; Weeks et al. 2008a, 2008b). Empirically, recent research has demonstrated that fears of both negative and positive evaluations lead to social anxiety and submissive withdrawal (Weeks et al. 2005). Also, research has indicated that fear of negative evaluation is the largest contribution to social anxiety compared with other variables (Teale Sapach et al. 2015). Thus, it is plausible to assume that fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety may serially mediate the effects of self-compassion on loneliness in adolescents, showing an indirect effect of self-compassion through fear of negative evaluation to social anxiety, then ultimately to loneliness (H3).

The Present Study

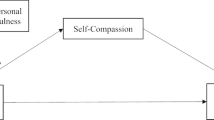

The present study seeks to explore the relationship between self-compassion and loneliness in adolescent samples and illuminate the roles of social anxiety and fear of negative evaluation by testing a multiple mediation model. Based on the review above, we hypothesized that there may exist two different models, with fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety mediating the link both parallelly and sequentially at the same time (Model 1), or only mediating the link parallelly (Model 2), see Fig. 1.

Accordingly, we raised the following three hypotheses:

-

H1: Self-compassion would be negatively associated with adolescents’ loneliness;

-

H2a: Social anxiety would mediate the relationship between self-compassion and loneliness in adolescents;

-

H2b: Fear of negative evaluation would mediate the relationship between self-compassion and loneliness in adolescents;

-

H3: Fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety serially mediate the effects of self-compassion on loneliness in adolescents.

Method

Participants

The convenient sampling method was used to collect data. As we were not sure of the appropriate sample size, we recruited as many participants as resources permitted prior to any data analysis (One grade, N = 871). A total of 871 students in senior one from 18 classes were finally recruited from a high school in Shanxi, China. All adolescents agreed to participate in our study completed and return the questionnaire after providing their and their parental informed consent. No respondents were removed or excluded, and all the 871 participants (Male = 469, 53.9%; Female = 395, 45.3%; Unreported = 7, 0.08%) were used for analyses, with age ranging from 13 to 18 years old (Mage = 15.18, SD = 0.10).

Measures

Loneliness

We measured adolescents’ loneliness through a 16-item self-report scale by Asher and Wheeler's (1985), items were rated on a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 5 (totally agree). The scale was translated into Chinese, and has shown good reliabilities in previous (e.g., Tian et al. 2012; Tian et al. 2014). The internal reliability in the present study was excellent (α = .91).

Self-Compassion

We measured adolescents’ self-compassion through the 26-items Self-Compassion Scale (SCS; Neff 2003b), which included three main components of self-compassion (e.g., “I’m kind to myself when I’m experiencing suffering.”) and their negative counterparts (e.g., “When I see aspects of myself that I don’t like, I get down on myself”). Participants were asked to rate each item on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Almost never) to 5 (Almost always). All items from three negative counterparts wound be reverse-coded and summed with the remaining items, with a higher mean score indicating higher self-compassion. Our measures demonstrated high internal consistency (α = .95). The Chinese version of the SCS has been demonstrated to be a reliable measurement in Chinese populations (e.g., Yang et al. 2019).

Social Anxiety

Social anxiety was assessed through the subscale of the Social Anxiety Scale (La Greca and Lopez 1998). The subscale comprises 6 items (e.g., “I get nervous when I meet new kids”), measuring adolescents’ social avoidance and distress in social situations with peers. Items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (all the time). Total scores are obtained by summing relevant items and can range from 6 to 30. Because there was no corresponding Chinese version of the scale, we invited two English major graduates with a background in psychology to translate and back translate the questionnaire (translation-back-translation procedure; Brislin 1970). The internal consistency is acceptable (α = .80). We also used confirmatory factor analysis to test its construct validity, and the indices (χ2 = 44.54, df = 9, χ2/ df = 4.95, CFI = 0.97, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.03) indicated an adequate fit of a single-factor model.

Fear of Negative Evaluation

Fear of negative evaluation was assessed using the subscale of the Social Anxiety Scale, which includes 8 items (e.g., “I worry about what other kids think of me.”). Participants were asked to rate each item on a scale of 1 (totally disagree) to 5 (totally agree). The same procedure of translation was used (Brislin 1970). This subscale demonstrated high internal consistency in the present study (α = .90). We also used confirmatory factor analysis to test its construct validity, and the indices (χ2 = 426.15, df = 20, χ2/ df = 21.31, CFI = 0.90, RMSEA = 0.15, SRMR = 0.05) indicated an acceptable fit of a single-factor model.

Statistical Analysis

SPSS 24.0 was used to calculate descriptive statistics and correlations of all the key variables. As for the missing data, mean substitutes were used for descriptive analyses by SPSS 24.0, and the measurement model and structural model would be tested by Mplus 7.4, the full information maximum likelihood method was used in the structural equation modeling analysis.

According to Anderson and Gerbing (1988), the one-step approach may not detect the presence of interpretational confounding, and it would result in fit being maximized at the expense of meaningful interpretability of the constructs. So, the present study used the two-step procedure which recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) to analyze the mediation effects. The measurement model was first tested to assess whether each of the latent variables was represented by its indicators, then test the structural model using maximum likelihood estimation (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2006) by Mplus 7.4 program if the measurement model was satisfactory.

To control for inflated measurement errors caused by multiple items for the latent variable, a parceling approach procedure was used to aggregate items to form manifest indicators per construct, in which we use the highest loadings to anchor each of the three parcels, and then placed lower loaded items with higher loaded items to create overall balanced parcels (Little et al. 2002). The measure of loneliness, social anxiety and fear of negative evaluation were unidimensional, so we examined the standardized factor loadings of each item from a single-factor model and then balanced the best and worst items across the parcels (Little et al. 2002). Since self-compassion was a multidimensional measure, we created a latent variable by three component-scores as parcels. Specifically, the linear combination of scores from each component were parceled and used as observed variables (parcel 1: self-kindness and the reverse scored self-judgment; parcel 2: common humanity and the reverse scored isolation; parcel 3: mindfulness and the reverse scored overidentification) based on theories (Neff 2003b). So, we created three parcels for the latent variable of self-compassion as prior studies did (e.g., Joeng and Turner 2015).

On the other hand, the measurement model and structural model would be considered acceptable when the CFI and TLI values are above .90, and the RMSEA and SRMR values are below .08 (Hu and Bentler 1999). The accelerated-bias-corrected bootstrap estimation procedure was used to test the significance of the indirect effects. In the procedure, the given sample size was randomly resampled 1000 times with replacement, and then 1000 estimations of the indirect effect were calculated. When the 95% confidence interval (CI) for an indirect effect did not include 0, the indirect effect was significant (MacKinnon et al. 2004).

Results

Preliminary Analysis

The post-hoc power analysis using G*Power revealed that the large sample (N = 871) and the effect size of r = − 0.413 provided sufficient power (around 100%) to detect key findings, using an alpha level of 0.05.

Table 1 shows the preliminary analysis results. The internal consistencies of self-compassion (including all the subscales), social anxiety, fear of negative evaluation and loneliness were all satisfactory. As expected, self-compassion was negatively associated with social anxiety, fear of evaluation and loneliness, while loneliness was positively associated with social anxiety and fear of negative evaluation. Besides, social anxiety was positively associated with fear of evaluation.

Measurement Model

The measurement model consisted of 4 latent constructs (self-compassion, fear of negative evaluation, social anxiety and loneliness). An initial test of the measurement model revealed a very satisfactory fit to the data: χ2/df = 3.740, p < .001, RMSEA = .056, SRMR = .035, CFI = .973, TLI = .964. All the factor loadings of the indicators of the latent variables were reliable (p < .001), suggesting that all the latent constructs were well represented by their respective indicators.

Structural Model

In order to determine which model fits our data better, we tested two models discussed above. The fit indices of model 1 were χ2 = 255.095, df = 69, χ2 /df = 3.697, p < .001, RMSEA = .056, SRMR = .036, CFI = .973, TLI = .965, model 2 were χ2 = 446.338, df = 70, χ2 /df = 6.376, p < .001, RMSEA = .079, SRMR = .073, CFI = .946, TLI = .929, revealing that both models were acceptable. A further comparison between Model 1 and Model 2 showed a significant chi-square difference, Δχ2 (1, 864) = 190.388, p < .001, indicating that Model 1 was the best model.

As shown in Fig 2, the serial mediation model’s results showed that self-compassion was negatively associated with fear of negative evaluation (β = −.584, p < .001), and with social anxiety (β = −.111, p < .05), while social anxiety was positively associated with fear of negative evaluation (β = .626, p < .001), and with loneliness (β = .334, p < .001). The total effect of self-compassion on loneliness was significant (β = −.474, p < .001, 95% CI = −.176 to −.059), while the direct effect of self-compassion on loneliness (β = −.356, p < .001) was also significant. Furthermore, as presented in Table 2, the mediation effect of social anxiety on self-compassion to loneliness was significant (β = −.122, p < .001, 95% CI = −.072 to −.002), while the mediation effect of fear of negative evaluation on the negative association was nonsignificant (β = .042, p > .05, 95% CI = −.031 to .115). Moreover, the indirect effect of fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety as serial mediators in the relation between self-compassion and loneliness was significant (β = −.037, p < .05, 95% CI = −.171 to −.073).

The finalized structural model with gender as covariable (N = 864). Note: Standardized coefficients are reported. The factor loadings were standardized. SC1-SC3 = three parcels of self-compassion; FNE1-FNE3 = three parcels of fear of negative evaluation; SA1-SA3 = three parcels of social anxiety; AL1-AL4 = four dimensions of loneliness. Form **p < 0.05, ***p < 0.01, c′ = direct effect, c = total effect

Discussion

In the present study, we used a relatively large Chinese adolescent sample to examine the association between self-compassion and loneliness, and further investigated the mediation effects of fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety underlying the relationship. Consistent with our hypotheses, adolescents with higher levels of self-compassion would experience decreased loneliness, with social anxiety serving as a mediator. In addition, the serial mediation model (self-compassion → fear of negative evaluation → social anxiety → loneliness) yielded a significant result, indicating that self-compassionate adolescents would experience less fear of negative evaluation and suffer less from social anxiety, thus protecting them from experiencing loneliness.

Consistent with the prior research that self-compassion is negatively associated with loneliness in adults (Akin 2010), we yielded a similar result in adolescent population. These findings reflect that self-compassion has great implications in mitigating individuals’ loneliness not only in adulthood, but also in adolescence. Self-compassionate individuals have stable self-worth and unconditional self-acceptance, view one’s imperfections and sufferings as human shared conditions, and be aware of present painful experiences in a balanced way (Neff 2003a, 2003b; Neff and Vonk 2009). These qualities may influence adolescents’ perception of evaluations about themselves and provide themselves feelings of warmth, kindness, and interconnectedness with the rest of humanity when they face negative events (Neff and Vonk 2009), which contribute to generating more positive and less negative self-feelings and helping them experience less feelings of loneliness (Akin 2010).

Furthermore, we found the positive linkage of fear of negative evaluation, social anxiety and loneliness. The results not only supported the positive association between loneliness and social anxiety (Meltzer et al. 2013), but also extended findings about associations between fear of negative evaluation and loneliness. Jackson et al. (2002) found that highly shy individuals considered themselves as having underdeveloped interpersonal skills, and reported experiencing less social support and more loneliness. Possibly, people who are afraid of receiving negative evaluations and easy to be anxious in social situations are relatively more focused on others’ disapproval, which hampers you from obtaining enough social connectedness and support, and thus contributes to loneliness.

With respect to the mediation effect of social anxiety, results suggested that adolescents with higher levels of self-compassion would have lower levels of social anxiety, and thus experiencing less feelings of loneliness. This finding provides more empirical evidence for the claim that individuals with higher levels of social anxiety would prefer to choose cognitive and behavioral avoidance strategies (McManus et al. 2008), which hinders individuals from getting involved in social activities and results in experiencing more loneliness. Also, self-compassion helps reduce individuals’ needs to engage in cognitive avoidance when facing difficulties and thus, have a buffering effect on psychological distress (Gill et al. 2018). When faced with new situations, adolescents with higher levels of self-compassion would use more positive strategies (e.g., positive comprehension and acceptance of new situation) to cope with challenges so that they could reduce the generation of social anxiety, which may lead to fewer cognitive and behavioral withdrawal, and experience less loneliness.

Another novel finding of the present study was the serial mediating effects of fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety, suggesting that self-compassionate adolescents may have fewer fear of negative evaluation and experience decreased social anxiety, which ultimately attenuated the possibility of going through loneliness. In line with prior studies, individuals with higher level of self-compassion would have greater abilities to keep negative situations in perspective and achieve more accurate self-evaluations, instead of having fear about others’ evaluations (Leary et al. 2007). Besides, self-compassionate individuals were less likely to become overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy and more able to cope with fears of negative evaluation since they can alter their relationships with themselves and other’s evaluations, and thus have impact on their feeling of social anxiety and loneliness (Gill et al. 2018; Neff 2003a). Our findings indicated that self-compassion might help adolescents decrease the attentional resources towards worrying about others’ view and be more adapt in social lives.

Limitations and Implications

The current study has several limitations. The primary limitation of this work is that the cross-sectional nature of the data does not allow us to draw inferences about the causal associations among variables. Future studies should extend findings by using longitudinal data or experimental methods to interpret the causal relationships between self-compassion and loneliness. Furthermore, the measures we used are all self-reports, which might be susceptible to bias such as the social approval effect or demand characteristics. Thus, researchers can use more objective measurement tools in the future. Finally, there may exists factors interplaying in the association between self-compassion and loneliness that were not included in this study.

Despite these limitations, the current research highlights the protective role of self-compassion on Chinese adolescents’ loneliness and emphasized the mediating roles of both fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety. From a theoretical perspective, our findings contributed to the limited but growing body of research that examines the functional role of self-compassion on social context, especially in adolescence. Furthermore, the present study indicated that fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety displayed different role in the relationship of self-compassion and loneliness, supported that the necessity to distinct fear of negative evaluation from social anxiety. From a practical perspective, the present research confirmed that apart from executing intervention programs aimed at improving social relations (e.g., social skills training, increasing social support, enhancing social networks) or changing internal characteristics (e.g., reducing expectations of rejection, enhancing interpersonal efficacy) to ameliorate loneliness (Jackson et al. 2002; Winningham and Pike 2007), interventions related to promoting the levels of self-compassion can also aid in gaining more realistic appraisal of oneself and establishing intimate social bonds so that benefit lonely people. The previous studies indicated that self-compassion can be cultivated and learned (Neff and Costigan 2014), and empirical results also proved the efficiency for self-compassion interventions. Germer and Neff (2013) developed an 8-week mindful self-compassion training program, and the results indicated that participants would report increase on self-compassion, and decrease in anxiety, stress, and emotional avoidance after finished the intervention plan. So, it is reasonable to take self-compassion interventions to promote adolescence’ self-compassion, which lead to decrease level of fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety, furthermore, reduce their feeling of loneliness. Our data also suggested that forming the habit of adopting a self-compassionate mindset in everyday life can help decrease social anxiety and fear of negative evaluations from others as well.

References

Akin, A. (2010). Self-compassion and loneliness. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 2(3).

Allen, A. B., & Leary, M. R. (2010). Self-compassion, stress, and coping. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(2), 107–118.

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423.

Arch, J. J., Brown, K. W., Dean, D. J., Landy, L. N., Brown, K. D., & Laudenslager, M. L. (2014). Self-compassion training modulates alpha-amylase, heart rate variability, and subjective responses to social evaluative threat in women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 42, 49–58.

Asher, S. R., & Wheeler, V. A. (1985). Children's loneliness: A comparison of rejected and neglected peer status. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 53(4), 500–505.

Baker, L. R., & McNulty, J. K. (2011). Self-compassion and relationship maintenance: The moderating roles of conscientiousness and gender. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(5), 853–873.

Blackie, R. A., & Kocovski, N. L. (2018). Examining the relationships among self-compassion, social anxiety, and post-event processing. Psychological Reports, 121(4), 669–689.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216.

Carleton, R. N., Collimore, K. C., & Asmundson, G. J. (2007). Social anxiety and fear of negative evaluation: Construct validity of the BFNE-II. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 21(1), 131–141.

Cheng, G., Zhang, D., & Ding, F. (2015). Self-esteem and fear of negative evaluation as mediators between family socioeconomic status and social anxiety in Chinese emerging adults. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(6), 569–576.

Clark, D. M., & Wells, A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In R. G. Heimberg, M. R. Liebowitz, D. A. Hope, & F. R. Schneier (Eds.), Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment (pp. 69–93). New York: Guilford Press.

Collins, W. A. & Steinberg, L. (2007). Adolescent development in interpersonal context. Handbook of child psychology, 3.

Germer, C. K., & Neff, K. D. (2013). Self-compassion in clinical practice. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69, 856–867.

Gill, C., Watson, L., Williams, C., & Chan, S. W. (2018). Social anxiety and self-compassion in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 69, 163–174.

Harris, R. A., Qualter, P., & Robinson, S. J. (2013). Loneliness trajectories from middle childhood to pre-adolescence: Impact on perceived health and sleep disturbance. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1295–1304.

Harwood, E. M., & Kocovski, N. L. (2017). Self-compassion induction reduces anticipatory anxiety among socially anxious students. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1544–1551.

Hawthorne, G. (2008). Perceived social isolation in a community sample: Its prevalence and correlates with aspects of peoples’ lives. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 43(2), 140–150.

Heimberg, R, G., Brozovich, F, A., & Rapee, R, M. (2010). A cognitive behavioral model of social anxiety disorder: Update and extension. In Social anxiety (pp. 395-422). Academic press.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Jackson, T. (2007). Protective self-presentation, sources of socialization, and loneliness among Australian adolescents and young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(6), 1552–1562.

Jackson, T., Fritch, A., Nagasaka, T., & Gunderson, J. (2002). Towards explaining the association between shyness and loneliness: A path analysis with American college students. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 30(3), 263–270.

Joeng, J. R., & Turner, S. L. (2015). Mediators between self-criticism and depression: Fear of compassion, self-compassion, and importance to others. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(3), 453–463.

Kocovski, N. L., & Endler, N. S. (2000). Social anxiety, self-regulation, and fear of negative evaluation. European Journal of Personality, 14(4), 347–358.

La Greca, A. M., & Lopez, N. (1998). Social anxiety among adolescents: Linkages with peer relations and friendships. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26(2), 83–94.

Leary, M. R. (1983). A brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9(3), 371–375.

Leary, M. R., Tate, E. B., Adams, C. E., Batts Allen, A., & Hancock, J. (2007). Self-compassion and reactions to unpleasant self-relevant events: The implications of treating oneself kindly. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(5), 887–904.

Liao, C., Liu, Q., & Zhang, J. (2014). The correlation between social anxiety and loneliness of left-behind children in rural China: Effect of coping style. Health, 6(14), 1714–1723.

Lim, M. H., Rodebaugh, T. L., Zyphur, M. J., & Gleeson, J. F. (2016). Loneliness over time: The crucial role of social anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(5), 620–630.

Little, T. D., Cunningham, W. A., Shahar, G., & Widaman, K. F. (2002). To parcel or not to parcel: Exploring the question, weighing the merits. Structural Equation Modeling, 9(2), 151–173.

Lyon, T, A. (2015). Self-compassion as a predictor of loneliness: The relationship between self-evaluation processes and perceptions of social connection.

MacKinnon, D. P., Lockwood, C. M., & Williams, J. (2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39(1), 99–128.

Mahon, N. E., Yarcheski, A., Yarcheski, T. J., Cannella, B. L., & Hanks, M. M. (2006). A meta-analytic study of predictors for loneliness during adolescence. Nursing Research, 55(5), 308–315.

McManus, F., Sacadura, C., & Clark, D. M. (2008). Why social anxiety persists: An experimental investigation of the role of safety behaviours as a maintaining factor. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 39(2), 147–161.

Meltzer, H., Bebbington, P., Dennis, M. S., Jenkins, R., McManus, S., & Brugha, T. S. (2013). Feelings of loneliness among adults with mental disorder. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 48(1), 5–13.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2006). Mplus: Statistical analyses with latent variables. User's guide. Los Angeles: Author

Nangle, D. W., Erdley, C. A., Newman, J. E., Mason, C. A., & Carpenter, E. M. (2003). Popularity, friendship quantity, and friendship quality: Interactive influences on children's loneliness and depression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 32(4), 546–555.

Neff, K. D. (2003a). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2(2), 85–101.

Neff, K. D. (2003b). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2(3), 223–250.

Neff, K, D., & Costigan, A, P. (2014). Self-compassion, Wellbeing, and Happiness. 114–119.

Neff, K. D., & Vonk, R. (2009). Self-compassion versus global self-esteem: Two different ways of relating to oneself. Journal of Personality, 77(1), 23–50.

Neff, K. D., Rude, S. S., & Kirkpatrick, K. L. (2007). An examination of self-compassion in relation to positive psychological functioning and personality traits. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(4), 908–916.

Potter, R. F., Yar, K., Francis, A. J., & Schuster, S. (2014). Self-compassion mediates the relationship between parentalcriticism and social anxiety. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 14(1), 33–43.

Roberts, R. K., Roberts, C. R., & Chen, Y. R. (1998). Suicidal thinking among adolescents with a history of attempted suicide. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 37(12), 1294–1300.

Sylvers, P., Lilienfeld, S. O., & LaPrairie, J. L. (2011). Differences between trait fear and trait anxiety: Implications for psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(1), 122–137.

Teale Sapach, M. J., Carleton, R. N., Mulvogue, M. K., Weeks, J. W., & Heimberg, R. G. (2015). Cognitive constructs and social anxiety disorder: Beyond fearing negative evaluation. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 44(1), 63–73.

Tian, L., Chen, G., Wang, S., & Zhang, W. (2012). 父母支持、友谊支持对早中期青少年孤独感和抑郁的影响 [effect of Paretal support and friendship support on loneliness and depression during early and middle adolescence]. 心理学报, 044(007), 944-956.

Tian, L., Zhang, W., & Chen, G. (2014). 父母支持、友谊质量对孤独感和抑郁的影响:检验个间接效应模型 [effect of parental support, friendship quality on loneliness and depression: To test an indirect effect model]. 心理学报, 46(2), 238-251.

Vanhalst, J., Goossens, L., Luyckx, K., Scholte, R. H., & Engels, R. C. (2013a). The development of loneliness from mid-to late adolescence: Trajectory classes, personality traits, and psychosocial functioning. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1305–1312.

Vanhalst, J., Rassart, J., Luyckx, K., Goossens, E., Apers, S., Goossens, L., Moons, P., & i-DETACH Investigators. & i-DETACH Investigators. (2013b). Trajectories of loneliness in adolescents with congenital heart disease: Associations with depressive symptoms and perceived health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(3), 342–349.

Watson, J., & Nesdale, D. (2012). Rejection sensitivity, social withdrawal, and loneliness in young adults. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 42(8), 1984–2005.

Weeks, J. W., Heimberg, R. G., Fresco, D. M., Hart, T. A., Turk, C. L., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2005). Empirical validation and psychometric evaluation of the brief fear of negative evaluation scale in patients with social anxiety disorder. Psychological Assessment, 17(2), 179–190.

Weeks, J. W., Heimberg, R. G., & Rodebaugh, T. L. (2008a). The fear of positive evaluation scale: Assessing a proposed cognitive component of social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(1), 44–55.

Weeks, J. W., Heimberg, R. G., Rodebaugh, T. L., & Norton, P. J. (2008b). Exploring the relationship between fear of positive evaluation and social anxiety. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(3), 386–400.

Werner, K. H., Jazaieri, H., Goldin, P. R., Ziv, M., Heimberg, R. G., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Self-compassion and social anxiety disorder. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 25(5), 543–558.

Winningham, R. G., & Pike, N. L. (2007). A cognitive intervention to enhance institutionalized older adults’ social support networks and decrease loneliness. Aging & Mental Health, 11(6), 716–721.

Yang, Y., Guo, Z., Kou, Y.*, & Liu, B. (2019). Linking Self-Compassion and Prosocial Behavior in Adolescents: The Mediating Roles of Relatedness and Trust. Child Indicators Research. 12(6), 2035-2049.

Funding

This research was sponsored by Shanghai Sailing Program (19YF1413400), China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2019 M651440), MOE (Ministry of Education) Youth Project of Humanities and Social Science (20YJC190026), The National Social Science Fund of China (19ZDA357) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (2019ECNU-HWFW019).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, X., Yang, Y., Wu, H. et al. The roles of fear of negative evaluation and social anxiety in the relationship between self-compassion and loneliness: a serial mediation model. Curr Psychol 41, 5249–5257 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01001-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-01001-x