Abstract

Purpose

Loneliness can affect people at any time and for some it can be an overwhelming feeling leading to negative thoughts and feelings. The current study, based on the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey in England, 2007, quantified the association of loneliness with a range of specific mental disorders and tested whether the relationship was influenced by formal and informal social participation and perceived social support.

Methods

Using a random probability sample design, 7,461 adults were interviewed in a cross-sectional national survey in England in 2007. Common Mental Disorders were assessed using the revised Clinical Interview Schedule; the diagnosis of psychosis was based on the administration of the Schedules of the Clinical Assessment of Neuropsychiatry, while loneliness was derived from an item in the Social Functioning Questionnaire.

Results

Feelings of loneliness were more prevalent in women (OR = 1.34, 95 % CI 1.20–1.50, P < 0.001) as well as in those who were single (OR = 2.24, 95 % CI 1.96–2.55, P < 0.001), widowed, divorced or separated (OR = 2.78, 95 % CI 2.38–3.23, P < 0.001), economically inactive (OR = 1.24, 95 % CI 1.11–1.44, P = 0.007), living in rented accommodation (OR = 1.73, 95 % CI 1.53–1.95, P < 0.001) or in debt (OR = 2.47, 95 % CI 2.07–1.50, P < 0.001). Loneliness was associated with all mental disorders, especially depression (OR = 10.85, 95 % CI 7.41–15.94, P < 0.001), phobia (OR = 11.66, 95 % CI 7.01–19.39, P < 0.001) and OCD (OR = 9.78, 95 % CI 5.68–16.86, P < 0.001). Inserting measures of formal and informal social participation and perceived social support into the logistic regression models did significantly reduce these odds ratios.

Conclusion

Increasing social support and opportunities for social interaction may be less beneficial than other strategies emphasising the importance of addressing maladaptive social cognition as an intervention for loneliness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Loneliness has been defined as an unwelcome feeling of lack or loss of companionship [1], a discrepancy between an individual’s perception and interpretation of what they have and what they desire [2] or a feeling of somehow being removed or dissociated from the world and the people in it [3]. Although all studies highlight that loneliness is different from solitude, loneliness is more prevalent among disabled people and those living in rural settings [4].

Studies that have investigated the relationship between loneliness and mental health propose loneliness as having a direct effect on feelings of depression or suicide [5] that may be mediated by major life events, such as loss of employment, breakdown of relationships, relocation, bereavement [3] highlighting solitude as a dimension in loneliness.

Studies on the relationship between loneliness and psychiatric morbidity have been paralleled by research looking at the effect of social relationships, social support and social networks on mental health. The early work examined loneliness as a mediator of stress [6] or as a moderator of well being [7], whereas more recent work has focused on the relationship between depression and social supports [8, 9]. The results from the first national survey of psychiatric morbidity in Great Britain [10] showed that a low level of perceived social support, a small primary support group and minimal involvement in social and leisure activities were all associated with a higher rate of common mental disorders. However, no measure of loneliness was included in the survey.

Very few studies have examined the prevalence of loneliness in large, national, representative samples, that is, covering men and women of all ages living in urban and rural settings, with the notable recent exception of one survey of 3,000 Australian adults [11]. Previous research has tended to concentrate on particular groups within the population. Older adults have been extensively covered-in the community [12, 13], in retirement communities [14], or in institutional care [15]. Other studies have looked at feelings of loneliness among young people [16–18], recent immigrants [19], homeless people [20, 21] and those living in remote communities [22, 23]. All of these studies highlight the association of loneliness with mental health problems, predominantly depression.

Reciprocal causality must be taken into account in considering the relationship between mental disorders and loneliness. Loneliness can be a risk factor for anxiety and depression, while anxious and depressed people may isolate themselves to reduce the stresses of life.

The relationship between loneliness and mental disorders is well established in studies of specific disorders: depression [24, 25]; anxiety—mainly among children [26]; and phobias—particularly social phobia [27]. The relationship between loneliness and psychosis has been viewed in psychoanalytical terms—the withdrawal into a fantasy world to cope with loneliness [28].

As no previous study has looked at loneliness across the age range in a national representative study and its relationship to a wide range of specific mental disorders, data were analysed from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007 (APMS 2007), a sample survey of all adults living in private households in England. The tested hypotheses were that (1) people with mental disorders will report high levels of loneliness, (2) co-morbid mental health problems will exacerbate feelings of loneliness, and (3) the relationship between loneliness and mental disorders will be influenced by relatively objective measures of social integration (in terms of frequent informal contact with friends, and involvement in formal social activities and organisations) as well as perceived social support.

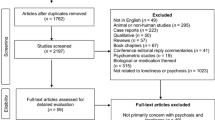

Methods

Sampling procedures

The third Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey was carried out in 2007 (29) as part of the extensive programme of national mental health surveys in Great Britain [30]. It was based on a stratified multi-stage random probability sample of adults living in households in England.

In the first phase of sampling, postcode sectors (on average 2,550 households) were stratified by socio-economic status within a regional breakdown. Postcode sectors were then sampled from each stratum with a probability proportional to size (where size was measured by the number of delivery points). In this way, a total of 519 postal sectors were selected.

In the second stage of sampling, 28 delivery points were randomly selected within each of the selected postal sectors. This yielded a total sample of 14,532 delivery points. Interviewers visited these addresses to identify private households with at least one person aged 16 and over. 9 % of the selected addresses did not contain private households, and were excluded. Within the potentially eligible sample of 13,171 addresses, interviews were sought with one person chosen at random from each household. The chosen residents, from 57 % of all eligible households, agreed to take part in the survey, yielding 7,461 participants in all.

Interviewers and interviewing procedures

Experienced interviewers from the National Centre for Social Research were selected to work on the survey, many of whom had worked previously on health-related surveys. Topics covered on the one-day survey-specific training included introducing the survey, the questionnaire content, confidentiality, and how to handle respondent distress. The fieldwork took place over the course of 1 year in 2007.

Instruments

Loneliness

All survey respondents were asked in the self-completion part of the interview the eight questions from the Social Functioning Questionnaire [31]. In question 7, respondents were presented with the statement “I feel lonely and isolated from other people” and then asked to rate their feelings in the past 2 weeks by choosing one of four response categories: very much, sometimes, not often or not at all. For analysis purposes, a dichotomous variable was created with very much or sometimes regarded as indicative of significant loneliness.

Common mental disorders (CMD)

Diagnoses of CMD were derived from responses to the revised Clinical Interview Schedule—the CIS-R [32]. Diagnostic algorithms were applied to the data to identify six categories of common mental disorder—generalised anxiety disorder, depression, obsessive–compulsive disorder, phobia, panic disorder, and mixed anxiety and depressive disorder. The latter is defined as having a CIS-R score of 12 or more, but falling short of the research diagnostic criteria for any other 5 Common Mental Disorders.

Psychosis

The probability of having a psychotic disorder was determined by taking in to consideration of the responses to several sections of the survey administered by interviewers and by a follow-up clinical interview. As part of the screening process information was gathered on whether respondents: (1) were currently on anti-psychotic medication, (2) had an inpatient stay for a mental or emotional problem in the past 3 months, or admission to a hospital or ward specialising in mental health problems at any time, (3) gave a positive response to auditory hallucination question in the Psychosis Screening Questionnaire [33], (4) self-reported a diagnosis of psychotic disorder or symptoms suggestive of it.

All respondents who met at least one of these criteria were approached for a SCAN (Schedules for the Clinical Assessment of Psychiatry) interview [34], a semi-structured interview that provides ICD-10 diagnoses of psychotic disorder. However, the term, “probable psychosis” is used here because the category includes SCAN non-respondents who met at least two psychosis screening criteria [35].

Indices of social participation and support

We used three measures of social participation and support. These can all be seen as broad indicators of social integration. The first can be termed informal social participation. It was derived from the question: “Thinking about all the people who do not live with you and whom you feel close to or regard as good friends, how many did you communicate with in the past week?” Answers ranged from 0 to 97 with a median value of 4. Hence, the sample was divided into those who reported communicating with 0–4 people and those who communicated with at least 5 people in the past week. The second measure was indicative formal social participation. Respondents were asked if they were actively involved in any of the following clubs or associations: sports or sport supporters club; hobby or interest group; political party, neighbourhood watch scheme, parent teacher association, tenants’ group, residents’ group, neighbourhood council, religious group or any other local group A binary variable was created, distinguishing people involved at any level from those who were not involved at all.

Finally, perceived social support was measured. This was based on the respondents’ ratings of seven items. After the introductory clause—there are people I know, among my family and friends—the items listed were: do things to make me happy, make me feel loved, can be relied on no matter what happens, would see that I am taken care of if I needed to be, accept me just as I am, make me feel an important part of their lives, and give me support and encouragement. Perceived social support was classified as severe lack, moderate lack and no lack. This set of questions has been used in UK national surveys over the past 25 years, in particular the Health and Lifestyle Survey [36] and the Health Survey for England [37].

Statistical analysis

SPSS (version 16.0) was used to analyse the survey data, as it allows for the use of clustered data inherent in complex survey designs. Initially, both univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were carried out to examine the association between socio-demographic and socio-economic variables and feelings of loneliness. Significant correlates were then carried forward as potential confounders in further multivariate logistic regression modelling to investigate the relationship between specific mental disorders and feelings of loneliness. These confounders have also been shown to have a significant relationship with common mental disorders [29].

We tested the extent to which social participation and support influenced the relationship between mental disorders and loneliness by inserting the three measures separately into the multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Weighting

Data were weighted to take account of non-response so that the results were representative of the household population aged 16 years and over in England. Weighting occurred in three steps. First, sample weights were applied to take account of the different probabilities of selecting respondents in different sized households. Second, to reduce household non-response bias, a household level weight was calculated from a logistic regression model using interviewer observation and area-level variables (collected from Census 2001 data) available for responding and non-responding households. Finally, weights were applied using the techniques of calibration weighting based on the age, sex and region to weight the data up to represent the structure of the national population, taking account of differential non-response between regions, and age-by-sex groups. The population control totals used were the Office for National Statistics (ONS) 2006 mid-year household population estimates. Young men have the worse response rates to surveys, and hence generally have bigger weights than other groups.

Results

About one in five adults in England, 18.0 % of men and 22.7 % of women, reported feeling lonely in the 2 weeks prior to interview.

Several socio-demographic and socio-economic factors were identified in unadjusted logistic regression analyses which increased the odds of loneliness (Table 1). Feelings of loneliness were more prevalent in women (OR = 1.34, 95 % CI 1.20–1.50, P < 0.001) as well as in those who were single (OR = 2.24, 95 % CI 1.96–2.55, P < 0.001), widowed, divorced or separated (OR = 2.78, 95 % CI 2.38–3.23, P < 0.001), economically inactive (OR = 1.24, 95 % CI 1.11–1,44, P = 0.007), living in rented accommodation (OR = 1.73, 95 % CI 1.53–1.95, P < 0.001) or in debt (OR = 2.47, 95 % CI 2.07–1.50, P < 0.001).

When all these factors were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model, all the characteristics were retained as significant correlates of loneliness apart from educational qualifications and being unemployed (Table 1). The largest adjusted odds ratios were found for those who were widowed, divorced or separated compared with married or cohabiting individuals (OR = 2.67, 95 % CI 2.25–3.17, 95 %, P < 0.001), being single (OR = 2.07, 95 % CI 1.76–2.43 P < 0.001), and for those in debt (OR = 1.95, 95 % CI 1.61–2.37, P < 0.001).

The data in Table 2 show strong correlations between loneliness and all mental disorders especially depression (OR = 10.85, 95 % CI 7.41–15.94, P < 0.001), phobia (OR = 11.66, 95 % CI 7.01–19.39, P < 0.001) and OCD (OR = 9.78, 95 % CI 5.68–16.86, P < 0.001). Table 2 also shows the marked effect of comorbid mental disorders with a 20-fold increase in feelings of loneliness for those with two (OR = 18.73, 95 % CI 11.92–29.43, P < 0.001) or three (OR = 22.83, 95 % CI 11.23–344.20, P < 0.001) mental disorders compared with the group with no mental disorder.

Formal and informal social participation and perceived social support all had an independent relationship with feelings of loneliness (Table 3). Having less than the median number of contacts per week doubled the likelihood of loneliness (OR = 1.99, 95 % CI 1.76–2.26, P < 0.001); the lack of active involvement in clubs was associated with approximately a 50 % increase (OR = 1.45, 95 % CI 1.24–1.60, P < 0.001), while a severe lack of social support quadrupled the odds (OR = 3.77, 95 % CI 3.12–4.56, P < 0.001).

Further analysis was carried out by inserting all three social integration variables into the logistic regression model, contact with friends and relatives and active involvement in clubs or associations had very little influence on the relationship between mental disorders and feelings of loneliness (Table 4). The increased odds of someone with any mental disorder when compared with someone without a mental disorder feeling lonely was 7.60, 95 % CI 6.56–8.81, P < 0.001 (adjusted for socio-demographic factors). Adjusting for social support reduced the odds minimally (OR = 7.42, 95 % CI 6.39–8.62. P < 0.001) with a similar result found for club participation (OR = 7.50, 95 % CI 6.48–8.69, P < 0.001). Level of social support did reduce the odds ratio, but only minimally (OR = 7.06, 95 % CI 6.08–8.20, P < 0.001).

Discussion

This study highlighted the strength of the association between loneliness and all the common mental disorders as well as with psychosis and the considerable impact of co-occurring disorders. However, people with common mental disorders even when they communicate with many other people and join clubs or associations seem to feel just as lonely as those who do not participate socially.

Socio-demographic and socio-economic correlates of loneliness

The socio-demographic and socio-economic factors associated with loneliness were similar to those found in the national survey in Australia [11]. Females were more likely to report loneliness than males and that the least lonely people were those in the older age groups. Both surveys, in Australia and England, also found the most marked differences by marital status. When compared with those living with a partner, single, separated, divorced or widowed people were far more likely to feel lonely. Childlessness did not appear to have an effect—the lack or loss of a partner was the key element [13]. Both surveys also showed that economically inactive people were lonelier than employed people and that relative poverty and indebtedness were also associated with feelings of loneliness. Those with time on their hands may not have the financial means to socialise.

Mental health problems and loneliness

All the common mental disorders were associated with increased odds of loneliness with depression and phobia having particular strong associations. The 11-fold increase in odds of loneliness for depression is an adjusted odds ratio—adjusted for age, sex ethnicity, marital status, employment, tenure and debt. This strong association has been found in other large scale epidemiological studies where adjustment was also made for age, gender, ethnicity, education, income, marital status, social support, and perceived stress [38].

For our analysis agoraphobia (with and without panic disorder), social phobia and specific isolated phobias were subsumed under the general category of phobia. An association with social and agoraphobia might be expected; loneliness has been linked to shyness, social withdrawal, poor quality social interaction with social discomfort and distrust, low self-esteem, and decreased feelings of social competency [38–40]. In addition, loneliness has been directly associated with social anxiety [41].

Mental disorders, loneliness and social participation

It appears that human interaction whether by conversation or in group settings may relieve the loneliness of people without mental disorders, but may have a minimal effect on those who are anxious or depressed. There may be several explanations for this somewhat surprising finding. First, the measures of social participation used in the survey are crude in that they do not give a measure of the extent, duration, nature or quality of the social interaction. Second, there may be differences in responses to loneliness depending on the severity of the mental disorder which in the current analysis is subsumed under one diagnostic category. Third, participation in social events may relieve a sense of solitude but not necessarily mitigate feelings of loneliness.

Should we intervene in loneliness?

Some argue that loneliness should command clinicians’ attention in its own right—not just as an adjunct to the treatment of other problems such as depression [40]. The findings of a recent study using careful cross-lagged methodology gave further emphasis to this—loneliness predicted depressive symptomatology, but the reverse was not true [42]. Importantly loneliness has also been shown to be related to mortality and suicide [43–45].

Loneliness also appears to be an important risk factor for poor physical health (in particular reduced immunity and elevated blood pressure) as well as alcohol misuse, and even the development of cognitive impairment and progression of Alzheimer’s disease [41, 46, 47]. There is a clear public health message that innovative policies need to be developed to help people overcome loneliness.

What interventions for loneliness?

A number of strategies for reducing feelings of loneliness have been developed; namely, improving social skills, enhancing social support, increasing opportunities for social interaction, and addressing maladaptive social cognition [48]. The results of our study suggest increasing social support and opportunities for social interaction are likely to be less beneficial than other strategies. In a meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness, Masi et al. [28] concur with our observation—in the analysis of randomised studies, interventions targeting maladaptive social cognition were more effective than those focusing on social support, increased social interaction, or social skills [48]. Research focusing on maladaptive cognition has often centred on cognitive and behavioural techniques, including identifying automatic negative thoughts, cognitive restructuring, and stress management [48]. Our study would suggest that any effective program would need to target those at particular risk, i.e. women (particularly aged 35–54), the widowed, divorced, or separated, those unemployed or economically inactive, or in debt.

Other possible management strategies include animal-assisted therapy; this has been found to be of benefit in older people in institutional environments [49].

Advantages and limitations of the study

The main advantages of our study include the sampling procedures that provided a large nationally representative community sample across the age spectrum, the ability to control for important confounding factors, and the use of well-validated instruments and epidemiological methods to detect common mental disorder. The main drawback is the cross-sectional design, thereby limiting the ability to examine causal relationships. Although the response rate of 57 % might potentially influence the results, very careful weighting procedures were performed to reduce potential non-response biases.

The principal objective of the 2007 Adult Psychiatric Survey in Great Britain was to estimate the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity according to diagnostic category in the adult household population in England [29]. The survey included the assessment of common mental disorders, psychosis, borderline and anti-social personality disorder, Asperger’s syndrome, substance misuse and dependence; and suicidal thoughts, attempts and self-harm. At the time, the survey was designed the sole question on loneliness was one item in the Social Functioning Questionnaire [31]. A full battery of questions of loneliness would have been preferable but there are limitations to use pre-existing sources of data, despite the many benefits. However, both the assessment of loneliness and the mental disorders have similar reference periods.

This study has highlighted the strong association between loneliness and mental disorder, especially depression and phobias. Being in contact with others whether talking or actively participating in a shared interest or even having a strong sense of social support does not mitigate the feelings of loneliness. Addressing loneliness is important, and interventions influencing social cognition in targeted ‘at risk’ populations need to be further evaluated.

References

Cattan M, Newell C, Bond J, White M (2003) Alleviating social isolation and loneliness among older people. Int J Mental Health Promot 5(3):20–30

Drennan J, Treacy M, Butler M, Bryne A, Fealy G, Frazer K, Irving K (2008) The experience of social and emotional loneliness among older people in Ireland. Ageing Soc 28:1113–1132

Hole K (2011) Loneliness compendium: examples from research and practice. JRF Programme paper: Neighbourhood Approaches to Loneliness, Joseph Rowntree Foundation. http://www.jrf.org.uk/sites/files/jrf/loneliness-neighbourhoods-engagement-full.pdf

Tidy C (2010) Social isolation—how to help patients be less lonely’ patient UK, EMIS, Document ID: 2791. http://www.patient.co.uk/doctor/Social-Isolation-How-to-Help-Patients-be-Less-Lonely.htm

Griffin J (2010) The lonely society? Mental Health Foundation, London. http://www.its-services.org.uk/silo/files/the-lonely-society.pdf

Cobb S (1976) Social support as a moderator of life stress. Psychosom Med 317:300–314

Turner RJ (1981) Social support as a contingency in psychological wellbeing. J Health Soc Behav 22:357–367

Kaplan GA, Roberts RE, Camacho TC, Coyne JC (1987) Psychosocial predictors of depression. Prospective evidence from the human population laboratory studies. Am J Epidemiol 125:206–220

Kawachi I, Colditz G, Ascherio A, Rimm E, Giovannucci E, Stampfer M, Willett W (1996) A prospective study of social networks in relation to total mortality and cardiovascular disease in men in the USA. J Epidemiol Commun Health 50:245–251

Meltzer H, Gill B, Petticrew K, Hinds K (1995) OPCS surveys of psychiatric morbidity in Great Britain, Report 3, economic activity and social functioning of adults with psychiatric disorders. HMSO, London

Hawthorne G (2008) Perceived social isolation in a community sample: its prevalence and correlates with aspects of people’s lives. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 43:140–150

Theeke LA (2010) Socio-demographic and health-related risks for loneliness and outcome differences by loneliness status in a sample of US older adults. Res Gerontol Nurs 3(2):113–125

Koropeckyi-Cox T (1998) Loneliness and depression in middle and old age: are the childless more vulnerable? J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 53(6):S303–S312

Adams KB, Sanders S, Auth EA (2004) Loneliness and depression in independent living retirement communities: risk and resilience factors. Aging Ment Health 8(6):475–485

Grenade L, Boldy D (2008) Social isolation and loneliness among older people: issues and future challenges in community and residential settings. Aust Health Rev 53(3):468–478

Henwood PG, Solano CH (1994) Loneliness in young children and their parents. J Genet Psychol 155(1):35–45

Junttila N, Vauras M (2009) Loneliness among school-aged children and their parents. Scand J Psychol 50(3):211–219

Williams EG (1983) Adolescent loneliness. Adolescence 18(69):51–66

Ponizovsky AM, Ritsner MS (2004) Patterns of loneliness in an immigrant population. Compr Psychiatry 45(5):408–414

Rokach A (2005) The causes of loneliness in homeless youth. J Psychol 139(5):469–480

Sumerlin JR (1995) Adaptation to homelessness: self-actualization, loneliness, and depression in street homeless men. Psychol Rep 77(1):295–314

Havens B, Hall M, Sylvestre G, Jivan T (2004) Social isolation and loneliness: differences between older rural and urban Manitobans. Can J Aging 23(2):129–140

Woodward JC, Frank BD (1988) Rural adolescent loneliness and coping strategies. Adolescence 23(91):559–565

Luanaigh CO, Lawlor BA (2008) Loneliness and the health of older people. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 23(12):1213–1221

Cacioppo JT, Hughes ME, Waite LJ, Hawkley LC, Thisted RA (2006) Loneliness as a specific risk factor for depressive symptoms: cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses. Psychol Aging 21(1):140–151

Stednitz JN, Epkins CC (2006) Girls’ and mothers’ social anxiety, social skills, and loneliness: associations after accounting for depressive symptoms. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 35(1):148–154

Marshall JR (1991) Social phobia. Helping patients who are disabled by fear. Postgrad Med 90(8):187–188, 191–192, 194

De Masi F (2006) Psychotic withdrawal and the overthrow of psychic reality. Int J Psychoanal 87(Pt 3):789–807

McManus S, Meltzer H, Brugha T, Bebbington P, Jenkins R (2009) Adult Psychiatric Morbidity in England, 2007: results of a household survey. National Centre for Social Research, London

Jenkins R, Meltzer H, Bebbington P, Brugha T, Farrell M, McManus S, Singleton N (2009) The British Mental Health Survey Programme: achievements and latest findings. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 44:899–904

Tyrer P, Nur A, Crawfoed M, Karlsen S, MacLean C, Rao B, Johnson T (2005) The social functioning questionnaire: a rapid and robust measure of perceived functioning. Int J Soc Psychiatr 51:265–275

Lewis G, Pelosi AJ, Araya R, Dunn G (1992) Measuring psychiatric disorder in the community: a standardised assessment for use by lay interviewers. Psychol Med 22:465–486

Bebbington P, Nayani T (1995) The psychosis screening questionnaire. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res 5:1–19

World Health Organisation, Division of Mental Health (1999) Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Version 2.1. WHO, Geneva

Sadler K, Bebbington P (2009) Psychosis. In: McManus S, Meltzer H, Brugha TS, Bebbington PE, Jenkins R (eds) Adult psychiatric morbidity in England, 2007: results of a household survey. The NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care, Leeds

Health Promotion Research Trust (1987) The Health and Lifestyle Survey

Breeze E, Maidment A, Bennett N, Flatley J, Carey S (1994) Health Survey for England 1992. HMSO, London

Cacioppo J, Hawkley L, Ernst J et al (2006) Loneliness within a nomological net: an evolutionary perspective. J Res Perspect 40:1054–1085

Hawkley L, Burleson M, Bernston G, Cacioppo J (2003) Loneliness in everyday life: cardiovascular activity, psychosocial context, and health behaviours. J Pers Soc Psychol 85:105–120

Heinrich LM, Gullone E (2006) The clinical significance of loneliness: a literature review. Clin Psychol Rev 26(6):695–718

Anderson C, Harvey R (1988) Discriminating between problems in living: an examination of measures of depression, loneliness, shyness, and social anxiety. J Soc Clin Psychol 6:482–491

Cacioppo J, Hawkley L, Thisted R (2010) Perceived isolation makes me sad: 5-year cross-lagged analyses of loneliness and depressive symptomatology in the Chicago Health, Aging and social relations study. Psychol Aging 25:453–463

Patterson AC, Veenstra G (2010) Loneliness and risk of mortality: a longitudinal investigation in Alameda County. California Soc Sci Med 71(1):181–186

Shiovitz-Ezra S, Ayalon L (2010) Situational versus chronic loneliness as risk factors for all-cause mortality. Int Psychogeriatr 22(3):455–462

Stravynski A, Boyer R (2001) Loneliness in relation to suicide ideation and parasuicide: a population-wide study. Suicide Life Threat Behav 31(1):32–40

Cacioppo J, Hawkley L (2009) Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends Cogn Sci 13:447–454

Wilson R, Krueger K, Arnold S et al (2007) Loneliness and risk of Alzheimer disease. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64:234–240

Masi C, Chen H-Y, Hawkley L, Cacioppo J A meta-analysis of interventions to reduce loneliness. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. doi:10.1177/1088868310377394

Nimer J, Lundahl B (2007) Animal-assisted therapy: a meta-analysis. Anthrozoos 20:225–238

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

An erratum to this article is available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00127-014-0977-y.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Meltzer, H., Bebbington, P., Dennis, M.S. et al. Feelings of loneliness among adults with mental disorder. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 48, 5–13 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0515-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-012-0515-8