While on my way to work in the middle of the day in any area of my city, I get catcalled by a variety of men on the street. If I walk home from work at dusk, the comments only intensify. Old men, young men. Creepy men, adolescent boys. Whoever. They might say something fairly “benign,” such as, “You have very beautiful eyes” or they might say something very frightening, such as (approximately), “I want to bang you, b*tch.” Or just make some utterly degrading animal sound, laughing and giving their buddies a round of high-fives. Or, worst of all, pull over (nice car, beat up car—any class of men has its bottom-feeders), making such sounds from their car, then driving away, laughing maniacally.

I do not appreciate these comments AT ALL. If you think I have beautiful eyes, then appreciate them from afar instead of whispering a comment in my ear while I’m walking past you. I don’t care what your ‘complimentary’ intentions are. I’m trying to get to my job or to walk home or to run some errands, or maybe I’m just enjoying the day. There’s nothing that will wipe the smile off of my face faster than these comments. My policy is to ignore any comments, although somehow I can’t help looking painfully shocked by a remark/drive-by yell. Additionally, sometimes these comments rattle me and I can’t do my job as well as I’d like. From an anonymous poster on the blog.

Stop Street Harassment (2009)

Abstract

The current research suggests that perceptions of stranger harassment experiences (i.e., experiencing unwanted sexual attention in public) are altered by the context of the situation. Study one investigated which elements of the situation (context) might be most influential in increasing fear and enjoyment of the catcalling experience. Attractiveness and age of the perpetrator, time of day, and whether the victim was alone or with friends were some of the categories that were selected as influencing both fear and enjoyment. Study two used a perspective taking methodology to ask women to predict a target character’s emotions, fears, and behaviors in harassment situations that varied by context. Results mirror the sexual harassment literature and suggest that harassment by younger and attractive men is viewed as less harassing. Exploratory analyses were also conducted with women’s personal experiences with stranger harassment as well as gender differences in perceptions. Context plays a vital role in interpretation of stranger harassment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Fairchild and Rudman (2008) demonstrated that stranger harassment is a very real, common and often unpleasant experience in the lives of women. Being catcalled, stared at, whistled at, and even groped and grabbed are monthly and weekly experiences, and for some women a daily experience. In their research, Fairchild and Rudman (2008) demonstrate that stranger harassment functions akin to unwanted sexual attention (a subset of the sexual harassment spectrum) by eliciting reactions of ignoring the behavior. The authors even provide evidence of frequent experiences of stranger harassment correlating with more body objectification and fear of rape. The quote at the start of this article and many of the other submissions to Stop Street Harassment (http://streetharassment.wordpress.com/), The Street Harassment Project (http://www.streetharassmentproject.org/), HollabackNYC (http://www.hollabacknyc.blogspot.com/), and related websites suggest that many women find the experience of stranger harassment to be frightening, unpleasant, and disruptive; women frequently describe themselves as frustrated, disgusted, and angered by the experience.

On the other hand, Fairchild’s (2009) dissertation provides some intriguing tidbits that suggest that the harassment experience may not be universally loathed by women. This is also demonstrated in popular press discussions of stranger harassment or street harassment in which some women declaim harassment as invasions of their personal space, while others enjoy the attention (Grossman 2008). The title of Grossman’s article sums it up: “Catcalling: creepy or a compliment?”

Individual differences may account for women’s varying acceptance and rejection of stranger harassment. Yet, anecdotal evidence suggests that the same woman may enjoy a compliment 1 day, and be infuriated by a catcall the next. It seems highly likely that the context of the situation in which the harassing behavior occurs can alter the perception and perspective of the target. In one situation, a mild catcall may be threatening, but in another, it may be complimentary. As the author of the quote at the beginning of this article notes, harassment comes from many different types of men and the severity changes as day turns to night. The current research seeks to elucidate what contextual effects influence the perception of stranger harassment.

Stranger harassment or street harassment can be defined as the “[sexual] harassment of women in public places by men who are strangers” (Bowman 1993, p. 519) and includes “both verbal and nonverbal behavior, such as wolf-whistles, leers, winks, grabs, pinches, catcalls, and street remarks; the remarks are frequently sexual in nature and comment evaluatively on a woman’s physical appearance or on her presence in public” (p. 523). While being the recipient of any of the above behaviors may indicate one has been stranger harassed, like sexual harassment, it is the perception of the target or victim that determines if the event was indeed harassing. Sexual harassment researchers have noted that the official definition of sexual harassment provided by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) defines sexual harassment in terms of the perception of the victim in regard to frequency, coerciveness, and welcomeness (Faley 1982; Pryor 1985; Katz et al. 1996; Golden et al. 2001). Harassment is in the eye of the beholder; in other words, it is up to the victim to label the behavior harassment. Sexual harassment, and by extension stranger harassment, is a matter of individual perception. This suggests that there are a multitude of potential individual and situational variables that can influence the perception of harassment.

Context Effects

While under the greater umbrella of sexual harassment, stranger harassment has been rarely studied (Fairchild and Rudman 2008). However, because of the similarities between stranger harassment and sexual harassment’s unwanted sexual attention, an understanding of the sexual harassment literature can shed light on how women react to stranger harassment. Because sexual harassment is defined by the perception of the victim, many researchers have investigated the individual and contextual differences that may influence a victim’s interpretation. Katz et al. (1996) note that researchers have investigated the influence of variables such as observer gender, harasser’s age and marital status, observer’s occupation, and the severity of harassment on perceptions of sexual harassment. LaRocca and Kromrey (1999) add to this list that many have also studied the effects of power and attractiveness (of both the harasser and victim) on perceptions. Finally, Golden et al. (2001) highlight that researchers have also investigated the effects of responses made by the victim to the harassment and the gender composition of the occupation.

In his article on the “lay person’s understanding of sexual harassment,” Pryor (1985) reviews past research on the factors that influence an observer’s perception of whether sexual harassment has occurred in an ambiguous situation.Footnote 1 These factors range from characteristics of the perpetrator, victim, and observer to the relationship between the perpetrator and victim. Overall, it is clear that the unwelcomed sexual attention of sexual harassment is up to the individual’s interpretation, which is affected by a myriad of factors. Pryor (1985) deduces from the past research and a small study that Kelly’s attribution theory can be applied to determine whether an observer will label an ambiguous behavior as sexual harassment. Understanding the context behind the harassment event, especially details about the harasser that signify the consistency, distinctiveness, and consensus of his behavior, are influential in determining whether sexual harassment has occurred.

Terpstra and Baker (1986) develop a framework for the study of sexual harassment that argues that the perception of the behavior is what determines the response to and outcomes of the behavior more so than the actual behavior itself. This is the result of individuals interpreting similar events differently; what is sexual harassment to one person, may be viewed as funny by another, and inconsequential by a third. These authors suggest that potential variables that might influence an individual’s perception of sexual harassment include: sex, age, marital status, attractiveness, familiarity status, and job status of the perpetrator; demographic, psychological, and work-related factors of the victim; sex-role identity and attitudes toward women of the observer. Like Pryor (1985), Terpstra and Baker (1986) suggest Kelly’s attribution theory may be a good explanation for causal attributions of sexual harassment.

Unfortunately, transferring the effects of context from the sexual harassment literature to stranger harassment is difficult. Because the perpetrator of a stranger harassment event is a stranger, it is impossible for the victim or even an observer to assess many of the attributes deemed important in determining the occurrence of sexual harassment through Kelly’s attribution theory as suggested by Pryor (1985) and Terpstra and Baker (1986). Victims can estimate age and attractiveness, but factors that would support Kelly’s attribution theory to demonstrate consistency, distinctiveness, and consensus of behavior are impossible to establish in a single episode. Moreover, the crucial outcomes of stranger harassment, such as the toll that it may take on women’s emotions, body image, and behaviors, are dependent on the individual woman perceiving the occurrence of harassment, not on an outside observer’s opinion of whether or not harassment occurred. While the use of Kelly’s attribution theory serves a good purpose in understanding how observers (who may be involved in determining the repercussions of a sexual harassment case) process and understand sexual harassment is useful knowledge, it is unhelpful in understanding what contextual effects may influence perceptions of stranger harassment.

Context Effects: Attractiveness of the Perpetrator

The contextual factor of attractiveness likely has an effect on the perception of harassment from both known and unknown others. The research on attractiveness and perceptions of sexual harassment suggest that the ambiguous behavior of attractive perpetrators is likely to be viewed as less sexual harassing than the same behaviors performed by unattractive perpetrators (Cartar et al. 1996; LaRocca and Kromrey 1999; Golden et al. 2001). LaRocca and Kromrey (1999) conducted a study in which participants read a vignette about an ambiguous sexual harassment situation; the attractiveness and gender of the perpetrator and victim were manipulated in each of the vignettes. Their results showed an interesting interaction between observer gender, perpetrator gender, and attractiveness. Both men and women viewed the opposite sex perpetrator as less harassing than the unattractive opposite sex perpetrator. In other words, for women, the behavior of the attractive male perpetrator in the vignette was rated as less harassing than the same behavior by an unattractive male perpetrator.

Golden et al. (2001) explain that the attractive perpetrator may be off the hook for his behaviors because of the attractiveness stereotype. Individuals who are attractive receive the benefit of the “halo effect” in which their attractiveness encourages others to ascribe positive traits and behaviors to them. An attractive individual may then be more likely to “get away with” ambiguous sexual harassment behaviors because of the additional good qualities he is assumed to have under the attractiveness stereotype. Because beautiful is believed to be good, the authors hypothesize that attractive male perpetrators will be viewed as less harassing in their behavior than unattractive male perpetrators. Their data support their hypothesis and they conclude that the effect of attractiveness on perceptions of sexual harassment stem directly from the stereotype of attractiveness. This supports the work of Trope (1986), Trope and Alfieri (1997) that suggests that elements of the context help to determine what happened in ambiguous situations.

For stranger harassment, these results suggest that attractiveness of the harasser may play a role in women’s perceptions regarding their own experiences. If an attractive man catcalls a woman, the woman may be more likely to view the incident as benign and potentially feel flattered. Likewise, a catcall from an unattractive man may lead to a more typical interpretation of the incident as harassment and a more negative reaction from the woman. Attractiveness of the perpetrator is a contextual factor that may have an effect on the perception of stranger harassment. While the behaviors of stranger harassment (catcalling, whistling, leering, etc.) are not as ambiguous as some of the unwanted sexual attention behaviors with sexual harassment, the intention behind the behaviors is ambiguous and therefore the victim is likely assessing the context to determine her emotional and physical reaction. Whistles from an attractive man may be perceived as less threatening than the same behavior from an unattractive man. What Cartar et al. (1996) suggest of sexual harassment is likely true for stranger harassment: “the male’s beauty would likely ‘soften’ the negative reaction of a female to his sexual advances” (p. 739).

Context Effects: Severity and Threat

Research by Cartar et al. (1996) investigated the relationship between attractiveness of the perpetrator and severity of the behaviors. The researchers predicted that varying the attractiveness of the perpetrator would have an effect on women’s perceptions of the situation including how flattered they felt, how violated, and how socially desirable the behavior was. In addition, the researchers predicted that varying the severity of the behavior would effect perceptions. Quite simply, they predicted that increasing the amount of coercion in the situation would increase the negative reaction in women; however, following prior research, women would regard all of the sexually coercive situations negatively, and that negativity would increase as the amount of coercion increases regardless of attractiveness of the perpetrator.

The researchers created three vignettes to represent low (gentle kiss), medium (touching of breast), and high (grabbing genitals) sexual coercion (Cartar et al. 1996). Each of the vignettes was described as being conducted by a very attractive or unattractive man. Participants rated the overall effect of the situation, social desirability of the actions, and how flattered they would feel. In addition, they rated how coercive the behavior was perceived to be and how attractive they believed the perpetrator to be. The results indicated that coercion and physical attractiveness were highly related. Specifically, as the men’s behavior became more coercive, their attractiveness decreased. In terms of flattery, the attractive male’s behavior in the least coercive condition was considered moderately flattering, followed by the unattractive male in the same condition whose behavior was considered moderately unflattering. The women did view all three acts as having a negative effect on them with the medium and high conditions being much more negative than the low condition.

Cartar et al. (1996) conclude that in low levels of coercion, women view themselves as objects of seduction and not as victims. This may come from the fact that they feel mildly flattered in these conditions; however, importantly, most of the women reported no interest in further sexual contact with the perpetrator. Overall, when the perpetrator is more attractive his behaviors (at least in the low and medium conditions) were viewed less harshly and as more flattering: “attractiveness of an opposite gender perpetrator alters how that person’s sexually coercive advances are perceived” (Cartar et al. 1996, p. 749).

Most incidents of stranger harassment represent low levels of coercion. Catcalls, whistles, and leers involve no physical contact. Fairchild and Rudman (2008) found that these types of unwanted sexual attention were the most frequently experienced by women and were experienced by the greatest number of women. Behaviors high in coercion such as groping and grabbing or unwanted sexual touching were less frequent and experienced by fewer women. This suggests that the behaviors indicative of stranger harassment may be more open to interpretation through context because of their low coercive nature. Being lower in coercion does not absolve the behavior of its negative effects (Cartar et al. (1996) demonstrated that low coercive behaviors still elicit a primarily negative effect), however, being lower in coercion allows stranger harassment behaviors to be more ambiguous in the intent of the harasser. A male harasser who leers at a woman may or may not have intentions or desires to pursue a sexual engagement; a male harasser who forcefully fondles a woman has a more clear sexual intent to his actions.

Level of coercion may be an imprecise stand-in for perceived amount of threat. Baker et al. (1990), in a study of reactions to sexual harassment, find that assessing perceived severity does not fully address the range of observed reactions. These authors suggest that instead of severity, a better measure might be the perceived level of threat. It is highly likely that the more threatening the behavior (e.g., forceful fondling), the more likely an assertive reaction or response is elicited. Thus it is presumed that “wolf-whistles” and obscene gestures will elicit more passive responses because they are viewed as less threatening. Baker et al. (1990) included whistles and obscene gestures in their study as forms of sexual harassment (performed by known others in the workplace) and found that they received passive reactions, such as ignoring. This fits with Fairchild and Rudman’s (2008) findings that most women respond passively to stranger harassment. However, their study did not assess the effect of context on reactions, which might, as Baker et al. (1990) suggest, alter women’s responses. In other words, while a catcall may appear low in severity, certain context effects (e.g., at night in an isolated location) may increase the perceived threat, thus changing the reaction of the victim to a potentially more active response.

Current Studies

The current studies were designed to assess which context effects may be important in the perception of stranger harassment and how those context effects may alter women’s emotions, fear of rape, and behavioral reactions. Study one presented women with an array of contextual influences regarding both the situation and the perpetrator. Perpetrator characteristics included attractiveness, age, and number of harassers. Situational characteristics included time of day, location, and whether the victim was alone or with others. Participants categorized each potential factor as to whether it would make a typical stranger harassment situation more frightening or more enjoyable. Based on the women’s categorizations in study one, study two was developed to assess how changing the context might alter women’s emotions, fear of rape, and behavioral reactions to a typical stranger harassment situation. Through the use of a vignette, participants were presented with the same typical stranger harassment situation which varied only in one contextual feature at a time. The women were asked to take the perspective of the target woman in the vignette and predict her emotions, fear of rape, and behavioral reactions. It was predicted that the changing context would alter the emotions, fear, and reactions that were ascribed to the target character in line with the findings from study one as to which elements of context make the situation more fearful or more enjoyable.

Study One: Determining Context

The first study was intended as an exploratory assessment of the contextual elements that may be involved in a stranger harassment experience. A list of contextual elements was developed by the researcher and research assistants based on personal experiences and anecdotal stories from acquaintances’ experiences. Additionally, the study sought to replicate the prevalence findings of Fairchild and Rudman (2008) in a non-college, internet sample.

Method

Participants

The survey received 1,698 responses. Eight individuals (.5%) declined the informed consent and did not complete the study. Twenty-seven individuals (1.7%) reported their sex as male; their data were dropped from the study. As Tuten et al. (2002) note, it is impossible to accurately assess response rates to Web-based surveys because unlike emailed or mailed surveys, the entirely Web-based survey is not addressed to a specific population; the common method for estimating response rates for Web-based surveys is to report the total number of useable participants. Of the remaining participants, 1,277 (76.8%) completed enough of the survey to be used in the data analysis.

The 1,277 remaining participants all reported their gender as female. The majority (87.2%) reported white for their race and heterosexual (74.2%) for their sexual orientation. The mean age of the participants was 28.11 years old (SD = 9.29); reported ages ranged from 15 to 71 years old.

Materials

Stranger Harassment

Experiences with stranger harassment were assessed using the modified version of the Sexual Experiences Questionnaire (SEQ; Fitzgerald et al. 1995) developed by Fairchild and Rudman (2008). Participants first responded “yes” or “no” to having ever experienced nine different behaviors from strangers that ranged in severity from unwanted sexual attention to forceful fondling (e.g., “Have you ever experienced unwanted sexual attention or interaction from a stranger?”; Have you ever experienced catcalls, whistles, or stares from a stranger?; “Have you ever experienced direct or explicit pressure to cooperate sexually from a stranger?”; and “Have you ever experienced direct or forceful fondling or grabbing from a stranger?”). Participants then responded to the same behaviors in terms of frequency regarding how often they had experienced each of the behaviors (1 = once; 2 = once a month; 3 = 2–4 times per month; 4 = every few days; 5 = every day). Table 1 provides a list of the behaviors.

Contextual Factors

Participants were presented with a list of 17 context factors including (attractiveness, time of day, race, and location) and asked to select which of the features would make a typical stranger harassment experience more fearful, which would make the experience more enjoyable, and which would make them more likely to react verbally (an active coping strategy). The active coping strategy of verbally responding is borrowed from Fitzgerald’s (1990) Coping with Harassment Questionnaire (CHQ). The items on this portion of the scale include: “I let him know I didn’t like what he was doing” and “I talked to someone about what happened.” These items are interpreted by Fairchild and Rudman (2008) to demonstrate active coping through verbally responding to the harasser in contrast to passive coping through ignoring the situation. Table 2 presents the context factors. Each of the questions was asked separately and the participants were allowed to select as many factors as they wanted for each question. The instructions simply stated that the participants were to think of a typical experience with strangers in public places as exemplified by the items they had responded to previously (the stranger harassment index items) and select the factors that would increase fear (or enjoyment or verbal response).

Procedure

In order to attract participants to the survey, the researcher and her research assistants posted the link in various web forums; the links advertising the study invited the participants to take part in a study on experiences in public places and importantly, the term stranger harassment was never used. Some websites were devoted to psychological research, while others were related to topics that women would be interested in (i.e., women’s magazines, knitting, health and fitness). When participants arrived at the website for the survey, they first read the informed consent, which was carefully worded to avoid using the term stranger harassment. If they consented to participate, they clicked the “next” button at the bottom of the screen. Each survey measure was presented on successive pages of the survey.Footnote 2 Participants were required to answer each question before being able to continue to the next measure. The components of the study were presented in the following order: demographics, Stranger Harassment Index (first “have you ever experienced…”, and then on the next page, “how frequently have you experienced…”), and Contextual factors (first fearful, then enjoyable, and finally more likely to respond verbally). After completing the survey, participants were debriefed with a final screen that described the study’s hypotheses regarding stranger harassment; this is the first and only time the words “stranger harassment” appeared in the survey. Participants could quit the study at any time by clicking “exit this survey” or by simply closing their web browser.

Results and Discussion

Prevalence of Stranger Harassment

Table 1 displays women’s reported frequencies of stranger harassment experiences. “Catcalls, whistles, or stares” and “unwanted sexual attention” were each reported to be experienced once a month by 29% of the sample. Further, 28% reported experiencing “catcalls, whistles, or stares” from strangers every few days or more. These percentages and those reported in Table 1 are inline with Fairchild and Rudman (2008). The current sample’s reported experiences are somewhat less frequent than those found by Fairchild and Rudman, but this is likely due to the near 10 year mean age difference between the samples (Fairchild and Rudman’s sample had a mean age of 19).

Contextual Factors

Participants responded to the contextual factors by selecting as many of the sixteen factors (or “none”) that would likely increase their fear, enjoyment, and likelihood to verbally respond to a typical stranger harassment situation. Table 2 displays the percentages of participants who selected each of the sixteen items or “none.” This table shows an interesting (yet logical) contrast between the contextual factors that increase fear and enjoyment. Twenty-seven percent of respondents selected that an attractive harasser would make the experience more enjoyable and 20% selected that an unattractive harasser would make the experience more fearful. This suggests that attractiveness of the perpetrator may function similarly to how attractiveness of the perpetrator functions in sexual harassment research; simply, similar behaviors from an attractive and unattractive man are viewed differently with the attractive man receiving more leeway in the potentially harassing behaviors. Likewise, there is a contrast between younger harasser (18% responded more enjoyable) and older harasser (33% responded more frightening); this suggests that age may be an important contextual factor, particularly for determining if a situation is threatening enough to induce fear. Being alone (72%) and nighttime (75%) were the most selected items for increasing the fear felt during a typical stranger harassment situation. Public places such as the street (35%), public transportation (32%), and parks/gardens (22%) were likely to be sites of more fear. Finally, 46% of respondents selected “none” in regard to what would make the situation more enjoyable. Because this data was a simple checklist, it can only be assumed that the women feel that stranger harassment is an unpleasant experience that cannot be improved. However, it is equally likely that these women (or some of them) find the experience highly enjoyable and such enjoyment cannot be increased. With this data set, it is impossible to interpret the “none” response.

In terms of what contextual factors would increase the likelihood that a woman would verbally respond demonstrating an active coping strategy (Fairchild and Rudman 2008), several factors were commonly selected. Fifty-three percent of respondents and 28% of respondents selected that they would be more likely to verbally respond if they were with a group of girlfriends or a male companion, respectively. In contrast to being alone eliciting more fear, it would seem that being with others would diffuse any threat in the situation and potentially inspire an active response. Taken together with 27% of women responding that a typical stranger harassment experience would be more enjoyable with a group of girlfriends, there may be less “harassment” viewed when with a group and more flirtation perceived. This speculation can be supported by the 24% of women who would be more likely to verbally respond to a situation in a bar/restaurant, which might indicate an acknowledgement of sexual attention through flirting as a more accepted practice in a bar and therefore more proclivity to say “I’m not interested.” Ultimately, these data cannot provide definite answers to what the women may have been thinking while responding. The speculation of dividing stranger harassment experiences into harassment and flirting needs to be tested through future research.

Overall, study one suggests that the sample surveyed are experiencing stranger harassment behaviors somewhat frequently. This mirrors the frequency rates found by Fairchild and Rudman (2008) even with a sample that is approximately 10 years older. In addition, this study highlights some of the important contextual factors that may play a role in women’s perceptions of stranger harassment as frightening or enjoyable and in women’s coping strategies (i.e., verbally responding). These factors include attractiveness and age of the perpetrator, time of day, location, and whether the woman is alone or with others. Study two was designed to manipulate some of these factors to assess direct differences in emotional reactions, fear, and coping.

Study Two: Manipulating Context

Based on the results of study one, study two asked participants to take the perspective of a target of stranger harassment and predict how she would feel and react. Research by Davis et al. (1996) suggests that when people take the perspective of another person, they readily ascribe their self-related traits to the target individual. Perspective taking is known to increase the cognitive overlap between the self and other; this overlap may become possible through the perspective taker asking herself how she would feel in the same situation (Davis et al. 1996). Additional research suggests that it does not matter whether a perspective taker is instructed to imagine herself or imagine the target (other) in the situation; both perspectives elicit empathy emotions (Baston et al. 1997). Baston et al. (1997) demonstrated that imaging the self in the situation also elicits feelings of personal distress, but these feelings of distress are more evident when the target is experiencing physical harm. Personal distress is less evident in situations involving psychological harm. Regardless, the experience of personal distress may add a dimension in which there is increased empathy and desire to help (Baston et al. 1997). In all, perspective taking seems an effective tool for indirectly assessing individuals’ reactions to a stranger harassment situation.

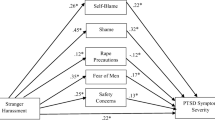

Study two presented participants with one of eleven vignettes and asked them to predict how the target woman would feel emotionally, how afraid she would be of rape, and how she would cope with the situation. The control vignette represented a generic stranger harassment situation without any direct manipulation of the event. Five pairs of alternate vignettes were created to manipulate attractiveness of the harasser, age of the harasser, whether the target was alone or with friends, time of day, and the number of harassers. It was hypothesized that women would predict a more negative emotional reaction, increased fear of rape, and more passive reactions to the vignettes that featured the unattractive harasser, the older harasser, being alone, nighttime, and a solo harasser. The opposing characteristics (attractive harasser, younger harasser, being with friends, daytime, and multiple harassers) were predicted to elicit a slightly less negative response on all three outcomes measures. The control vignette was predicted to fall in the between the scores for each pair.

Method

Participants

The survey received 818 responses. One individual declined the informed consent and did not complete the study. Eighty-six individuals (10.5%) reported their sex as male; their data will be discussed separately. Of the remaining participants, 464 (63.3%) completed enough of the survey to be used in the data analysis.

The 464 remaining participants all reported their gender as female. The majority (82.1%) reported white for their race and heterosexual (83.0%) for their sexual orientation. The mean age of the participants was 29.76 years old (SD = 10.49); reported ages ranged from 14 to 65 years old. Fifty percent of the participants reported living in an urban setting and 37% reported living in a suburban setting.

Materials

Stranger Harassment

Study two employed the same measure for stranger harassment that is described for study one. This measure was used to assess the participants’ frequency of experiences with stranger harassment.

Contextual Effects

To study the effects of manipulating the context on the perceived emotions and behavioral reactions of the target character, a brief vignette that could be easily modified was created. The control condition presented the basic vignette without any manipulation and reflects a typical stranger harassment experience: “Angie is walking down the street. She notices a man sitting on a bench. As she passes the man, he calls out to her ‘Hey, sexy baby. Looking hot today!’” Five pairs of alternate vignettes were created to manipulate attractiveness of the harasser, age of the harasser, whether the target was alone or with friends, time of day, and the number of harassers. Each of the alternate vignettes maintained the same basic plot of the control condition, but inserted descriptions that were intended to focus the reader on the desired manipulation. For attractiveness, the new vignette read: “Angie is walking down the street. She notices a very attractive (very unattractive) man sitting on a bench. As she passes the man, he calls out to her ‘Hey, sexy baby. Looking hot today!’” (italics added for emphasis). To manipulate the age of the harasser, the phrase “who appears about 15 years younger” or “who appears about 15 years older” was inserted into the control vignette. To manipulate whether the target woman was alone or with friends, the phrase “alone” or “with two friends” was added. To manipulate time of day, the phrase “at night” or “during the day” was included. Finally, to manipulate the number of harassers, the phrase “sitting alone” or “sitting with two other men” was incorporated into the vignette.

Predicted Outcomes

In order to assess women’s predictions of the target’s emotional state, participants were prompted with: “Imagine how Angie would feel in the situation just described and answer the following questions from her point of view.” Participants then rated the target’s emotions on a 6-point Likert scale from not at all to very much. The eleven emotions included: happy, indifferent, disgusted, anxious, complimented, nervous, excited, joyous, angry, fearful, and sad. The positive emotions were reverse scored and the combined emotions scale was created with a high score reflecting more negative emotion (α = .88).

Participants were asked to predict how fearful the target woman would be in her day-to-day life of being raped by a stranger and being raped by an acquaintance. Fear was rated on a 10-point Likert scale from not at all to very much. Because fear of rape by a stranger and an acquaintance were highly correlated (r = .75), the two items were averaged into the Fear of Rape scale (α = .86). Likewise, two items assessing fear of harassment (being a victim of unwanted sexual attention and being a victim of sexual harassment) were highly correlated (r = .79) and averaged to create the Fear of Harassment scale (α = .88). Fear of rape and fear of harassment were assessed separately from negative emotions because each may represent a more motivational factor than that assessed by negative emotions. Feeling angry, sad, or disgusted may or may not motivate behavioral changes in the woman, but research by Fisher and Sloan (2003) and Hickman and Muehlenhard (1997) suggest that fear of rape motivates precautionary behaviors. Hickman and Muehlenhard (1997) specifically found that as women’s fear of rape increased, so did their precautionary behaviors. Fairchild and Rudman (2008) found that fear of rape was positively correlated with women restricting their movement in public places (i.e., avoiding areas where harassment may occur), but that stranger harassment was not directly linked to such precautionary behaviors. While the current study does not specifically assess precautionary behaviors, it is assumed the fear of rape (and fear of harassment) may be motivational stand-ins for behavioral intentions, and that manipulation of the context may heighten or lessen these fears.

Participants were asked to rate the severity of the situation with one question that assessed how threatening the target character would perceive the situation to be; this Likert scale was anchored from “not at all threatening” (1) to “very threatening” (7).

Participants rated how likely the target would be to have 21 different thoughts and reactions. The thoughts and reactions were taken from the Coping with Stranger Harassment Scale that Fairchild and Rudman (2008) created based on the Coping with Harassment Questionnaire (CHQ; Fitzgerald 1990). The items represent passive, active, self-blame, and benign coping strategies. The active items (e.g., “I let him know I didn’t like what he was doing”) were predicted to be less frequently attributed to the target than the passive items (e.g., “I pretended nothing was happening”). Study one suggested that active (i.e., verbal) responses to stranger harassment were only likely in a few situations, such as when with girlfriends or during the daytime. In regard to whether the participants would predict that the target would see the experience as though it were benign (e.g., “I considered it flattering”), it was predicted that the same conditions that would elicit slightly less negative emotion would elicit slightly more benign reactions (i.e., perceiving less threat). There were no a priori predictions about the amount of self-blame (e.g., “I realized I had probably brought it on myself”) participants would ascribe to the target. The four coping scales had adequate reliability (all αs > .70).

Finally, participants predicted how likely it was for the target to ascribe to beliefs that would represent a vain personality. Netemeyer et al.’s (1995) Vanity Scale’s subscale for physical concern was included to assess whether the participants might view the target as seeking attention from men. Physical concern (α = .94) relates to worry about one’s appearance (e.g., “I am very concerned about my appearance”; “I would feel embarrassed if I was around people and did not look my best”). It is speculated that an individual with a vain personality might seek out attention and comments from strangers. If participants perceive the target as vain, this should correlate strongly with them perceiving her as enjoying the experience more. In her dissertation, Fairchild (2009) found that physical concern vanity was positively correlated with stranger harassment. She speculated that women who are more concerned with their appearance (physical concern vanity) may be more likely to dress in ways that attract stranger harassment. If female participants view the target as vain, they may have less empathy for her (in terms of perspective taking) and produce results that show more enjoyment and less fear.

Procedure

The procedure for obtaining participants and the survey hosting was identical to study one. Additionally, as in study one, the term stranger harassment did not appear in the informed consent or in the survey until the debriefing page. Once participants reached the survey, they were presented with an informed consent. Their demographic information was asked first followed by the randomization procedure for the vignettes. After reading their assigned vignette, the participants responded to the emotion items, fear of rape items, vanity items, and coping items. Finally, the participants reported their own experiences with stranger harassment and the frequency of those experiences.

Results

Prevalence of Stranger Harassment

Table 3 displays women’s reported frequencies of stranger harassment experiences. “Catcalls, whistles, or stares” and “unwanted sexual attention” were each reported to be experienced once a month by 24% of the sample. Further, 27% reported experiencing “catcalls, whistles, or stares” from strangers every few days or more. These percentages and those reported in Table 3 are similar to those found in Study one.

Contextual Factors

Collapsing across vignettes, the participants viewed the harassment as emotionally negative (M = 4.35, SD = .90). They also predicted that the target character would experience moderate amounts of fear of rape (M = 4.58, SD = 2.62) and fear of harassment (M = 5.98, SD = 2.68). Severity was rated to be moderate on a 1–7 scale (M = 4.06, SD = 1.36). The target character was rated as moderately vain (M = 3.50, SD = .97), but low in likelihood to use self-blame coping strategies (M = 2.34, SD = 1.07). Overall, the target character was predicted to frequently use passive coping strategies (M = 4.45, SD = 1.05), but to use benign (M = 2.37, SD = .91) or active (M = 2.55, SD = .97) coping strategies only moderately.

Correlations between the independent variables (collapsing across vignettes) show a logical pattern (see Table 4). Negative emotion is strongly positively correlated with fear of rape, fear of harassment, and ascribing a high amount of severity/threat to the situation. Predictions of negative emotions in the target character were positively correlated with her adopting passive and active coping strategies, and negatively correlated with viewing the situation as benign. Fear of harassment and severity were both positively correlated with self-blame and active coping strategies, yet negatively correlated benign strategies. Finally, predictions that the target character was vain were positively correlated with all outcome measures except for passive coping strategies.

An ANOVA was conducted to assess the effects of the 11 vignettes on the dependent variables: emotion, fear of rape, fear of harassment, severity, vanity, passive coping strategies, self-blame coping strategies, benign coping strategies, and active coping strategies. Even though the trials ranged in number of participants from 25 to 46, the test of equal variances was not violated.

Several significant results were highlighted in the ANOVA. First, there was a significant effect of trial on emotion (F(10, 400) = 6.98, p = .00). Second, there was a significant effect of trial on the predicted use of benign coping strategies (F(10, 400) = 2.28, p = .01). Finally, there was a significant effect of trial on the perceived severity or threat of the situation (F(9, 231) = 3.69, p = .00).Footnote 3 None of the remaining dependent variables illustrated significant differences because of trial (all Fs(10, 400) < 1.64, all ps < .10).

Tukey’s post-hoc tests elaborate the significant differences found through the ANOVA. Table 5 presents the mean comparisons for the vignettes that differed significantly in the post-hoc tests. The comparisons in Table 5 suggest that less negative emotion was experienced in the condition with the attractive harasser (2) than the conditions with the older man (5), at night (8), and a single harasser (10). The younger man (4) also elicited less negative emotion than the older man (5), being alone (6), at night (8), a single harasser (10), or multiple harassers (11). Being with two girlfriends (7) was viewed as less negative emotionally than the conditions with the older man (5), alone (6), at night (8), or a single harasser (10). Interestingly for emotions, the control condition was viewed as more negative than the conditions with the attractive man (2), the younger man (4), and with two girlfriends (7). For severity/threat of the situation, the younger man (4) is viewed as more benign and less threatening than the control condition (1) and night condition (8). Finally, the younger man (4) is viewed as less threatening than the conditions with a single harasser (10) and multiple harassers (11). Post hoc tests did not reveal any specific effects for the vignettes on benign coping strategies.

Stranger Harassment Experiences

To assess if participants’ own experiences with stranger harassment were reflected in their responses, correlations between the stranger harassment scale (SHS) and the outcome measures were analyzed. Scores on the SHS were positively correlated with negative emotions, fear of rape, fear of harassment, passive coping strategies, and self-blame (all rs > .12, all ps < .05). Additionally, SHS was negatively correlated with viewing the harassment situation as benign (r = −.10, p = .05). Differences between high and low scorers on SHS were assessed via t-test on the dependent measures. Because of very small Ns for each vignette when splitting participants based on SHS scores over and under the mean, all analyses were collapsed across vignette. Significant differences for participants scoring above (M = 4.47, SD = .91) and below (M = 4.24, SD = .86) the mean on SHS were found on negative emotions (t(404) = 2.57, p = .01). Female participants who more frequently experience stranger harassment themselves predicted more negative emotions from the situation presented in the vignette. On the measure of fear of rape, women with more frequent experiences of stranger harassment predicted higher fears of rape for the target (M = 4.96, SD = 2.49) than women with fewer stranger harassment experiences (M = 4.33, SD = 2.62; t(423) = 2.48, p = .01). The same pattern is seen for fear of harassment with high SHS predicting higher fears of harassment (M = 6.91, SD = 2.49) than low SHS (M = 5.30, SD = 2.57; t(426) = 6.49, p = .00). Women scoring high on SHS viewed the target as more likely to use passive strategies (M = 4.64, SD = .96) than women scoring lower on SHS (M = 4.33, SD = 1.06; t(416) = 3.14, p = .002). High SHS scores predicted viewing the harassment as less benign (M = 2.28, SD = .95) than low SHS (M = 2.51, p = .88; t(422) = 2.59, p = .01). Interestingly, high SHS scores predicted more self-blame (M = 2.50, SD = 1.16) than low SHS scores (M = 2.26, SD = .98; t(422) = 2.32, p = .02).

Gender Differences

Finally, using the sample of 86 men who were removed from the above analyses along with an additional 16 male participants collected in a psychology class, gender differences were compared between 102 male and 102 female subjects. The 102 female subjects were randomly selected via SPSS from the larger female data set. Demographic statistics and means for this subsample were not significantly different from the means and statistics reported above. Because of the small Ns per vignette cell, the analyses were collapsed across vignette to explore any gender differences.

The results demonstrated a clear distinction in men’s and women’s interpretations of the harassment situation. In terms of emotions, vanity, and two of the four strategies for dealing with harassment (benign and active), t-tests showed a significant difference in men’s and women’s responses (see Table 6). These results suggest that men perceive the stranger harassment situation as less negative emotionally than women. In addition, men believed that the target character was more vain than women believed and that the target character was more likely to brush off the harassment as benign and harmless. Finally, men were more likely than women to believe that the target character would employ active strategies such as confronting the harasser. No gender differences were found between men and women in perceptions of the target character’s fear of rapeFootnote 4 or use of passive and self-blame strategies.

Correlational data from the men provide some interesting clues to the gender differences. The male participants completed the Tolerance of Sexual Harassment scale (Lott et al. 1982), which assesses how tolerant a man is of sexual harassment in everyday life. High scores on this scale indicate that men are more tolerant or accepting of sexual harassment. Correlations with the dependent measures suggest that men who are tolerant of sexual harassment are more likely to see stranger harassment as an enjoyable experience for women (r = −.47, p < .01). In addition, there is a relationship between tolerance of sexual harassment and the target using self-blame strategies (r = .25, p < .05). This suggests that men who tolerate sexual harassment believe in part that women provoke or encourage such behavior.

Discussion

Study one illuminated some of the important factors that may play a role in women’s perceptions of stranger harassment situations. Age and attractiveness of the harasser, time of day, location, and whether the woman is alone or with friends were all implicated in making a harassment situation more frightening or more enjoyable. There was also some evidence that manipulating these context factors would inspire women to more actively respond to their harassers. Study two was conducted to manipulate these factors and to have participants adopt the perspective of the harassed woman and predict her responses. Study two predicted that the stories featuring an unattractive harasser, an older harasser, a solo harasser, the woman being alone, and nighttime would elicit predictions of more negative emotion, increased fear of rape and harassment, and more passive reactions or coping strategies. The opposing context factors were predicted to produce slightly less negative emotion, fear, and passive strategies.

Context Effects

The results of study two provide some support for the hypotheses as well as some interesting results. The ANOVA highlighted a significant effect of the vignettes or context factors on negative emotion, but not fears of rape and harassment, or passive coping strategies. Across all conditions, the target woman was predicted to be equally fearful and to as frequently use passive coping strategies to ignore the harassment. In other words, context effects did not affect a woman’s level of fear or first tendency to ignore the event. For negative emotions, the pattern of results fits the predictions from study one: an attractive or younger harasser and being with friends would elicit less negative emotion than the other conditions. Less negative emotion was experienced in the condition with the attractive harasser and the younger harasser than the conditions with the older man, at night, and a single harasser; the younger harasser also elicited less negative emotion than being alone and having multiple harassers. This reflects the findings in the sexual harassment literature that the behavior of attractive men is viewed to be less harassing than the behavior of less attractive men (Cartar et al. 1996; LaRocca and Kromrey 1999; Golden et al. 2001). In addition, the post-hoc tests revealed that as predicted being with two girlfriends was viewed as less negative emotionally than the conditions with the older man, alone, at night, or a single harasser. This may reflect a “safety in numbers” mentality, but because being with friends had no effect on fears of rape and harassment or actively responding, it may be a false or fleeting sense of safety. An alternative explanation may be that being with girlfriends allows women to defuse the situation by discussing, laughing about, or ranting about the situation. Additional research could unveil why being with friends slightly lessens the negative emotions of the harassment experience. The most interesting finding regarding emotions was that the control condition was viewed as more negative than the conditions with the attractive man, the younger man, and with two girlfriends. This was not predicted and presents a curious result. Because the control condition did not include details about the harasser, harassee, or situation, it is quite likely that participants added their own interpretations to the story or possibly even elaborated the story with their own personal experiences. Future research is needed to tease out why the control condition elicited greater predictions of negative emotion.

The context effects in the vignettes produced two other noteworthy, but not predicted, differences. First there was a significant effect on benign coping strategies. This effect was driven by a difference between the younger man condition and the control and night conditions. The data suggests that women predicted that the target character would be more likely to view the harassment as harmless or a joke when the harasser is younger than the target woman in comparison to the at night or control conditions. This is mirrored in that the younger man was also viewed as less threatening than the same conditions, as well as the conditions with a single harasser and multiple harassers. Age appears to be an important factor in determining the threat that the harasser poses. A strong negative correlation between severity/threat and benign coping strategies further solidifies the idea that less threatening situations are able to be viewed as meaningless or jokes. Likewise, the predicted emotional reactions show that the younger man elicits less negative emotion than many of the other conditions. The current research only addressed benign strategies (viewing the harassment as a joke) and did not investigate viewing the harassment as a compliment. Future research should attempt to use these context effects to determine if and when harassment many be viewed as not only benign, but complimentary.

Correlation Results

Collapsing across the scenarios, the correlations between the dependent measures followed the predictable pattern. Stronger negative emotion was positively correlated with more fear of rape and harassment and viewing the situation as severe/threatening. In addition, negative emotions were positively correlated with adopting passive and active coping strategies. The means suggest that passive strategies are more common than active coping strategies; in other words, women are more likely to ignore the harassment than to verbally respond with disapproval to the harassment. Additional research is needed to assess which negative emotions are correlating with each coping strategy. A quick correlational analysis revealed a strong correlation between active coping strategies and anger, disgust, fear, and anxiety (rs > .11, ps < .05); no correlations between the individual emotions and passive coping strategies was found. Finally, negative emotion was negatively correlated with benign coping strategies, which clearly indicates that negative emotions are not compatible with thinking of the harassment as meaningless or a joke.

Additional correlations of note include the positive correlation between fear of harassment and severity with self-blame and active coping strategies. These correlations seem to suggest that more perceived fear and perceived severity are related to more thoughts of “I brought this on myself.” Likewise, more fear and severity are related to taking an active stance and defending oneself from the harassment. As with the correlation between negative emotions and passive and active coping strategies, there is more research needed to tease apart which aspects of fear of harassment and severity drive some women to predict self-blame and others to predict active coping. The negative correlation between fear of harassment as well as severity with benign coping strategies is logical; the more fearful and severe the harassment, the less likely it is to be viewed as a joke.

The final correlations of interest about which there were not a priori predictions are vanity and the remaining outcome measures. Participants perceptions of vanity in the target character (without any more information about her than the simple vignette story) were positively correlated to their ratings on fear of rape, fear of harassment, severity/threat, and self-blame, benign, and active coping strategies. The most understandable of these correlations is between vanity and self-blame; the assumption may be made by the participants that a vain individual (interested highly in her own looks) is seeking attention and yet when she receives it as harassment, recognizes that she brought the situation on herself. An explanation for the other correlations is unclear at this time. The author is currently conducting research on the attractiveness and sexiness of the target to elaborate on the effects of perceived vanity on these and other outcomes measures.

Exploratory Analyses

Several exploratory analyses were conducted to assess the effect of participants’ own experiences with stranger harassment as well as the possible gender differences in perceptions of the outcomes of the harassment experience. Because participants’ own experiences with stranger harassment were correlated with the outcome measures, additional analyses were conducted to explore the nature of personal experiences on their predictions for the target character. A mean-split was used because the nature of the investigation was preliminary and a more refined analysis ought to start with a more thorough picture of participants’ stranger harassment experiences. The t-tests showed significant differences between participants scoring above and below the mean on the stranger harassment scale (SHS). Females with more personal experience of stranger harassment predicted that the target character would feel more negative emotions. This suggests that women with more experience of stranger harassment are more familiar with their own negative emotional reaction and ascribe that to the target character. As Davis et al. (1996) suggest, perspective taking leads individuals to ascribe self-related traits to the target. This is also demonstrated in the difference in scores for fear of rape and fear of harassment. Women with more experiences with stranger harassment predicted the target would be more fearful of both rape and harassment. Additionally, women scoring higher on the SHS predicted the target woman would be passive in dealing with the harassment and not likely to view the situation as benign. Again, these results suggest that women with more experiences of stranger harassment ascribe to the target character the characteristics and reactions that are typical of women who are harassed (see Fairchild and Rudman 2008). Finally, there was an odd finding that women high in SHS predicted more self-blame than women low in SHS. The means in both cases are on the low side of self-blame (less than 2.5 on a 6 point scale), thus it is not clear if this difference is an artifact or suggests that women who experience more stranger harassment may actually blame themselves and thus blame the target character. More research is needed to elaborate the connection between women’s experiences and their reactions.

An exploratory analysis was also conducted on a subsample of the women’s responses to compare them with a sample of men’s responses. The t-tests demonstrated a clear and distinct difference between men’s and women’s predicted reactions for the target character. Mirroring the research on gender differences in sexual harassment (e.g., Katz et al. 1996), these analyses showed that women viewed the situation as creating more negative emotions, as less benign, and the target as less likely to use active coping strategies. Research on sexual harassment suggests that ambiguous situations and hostile environment sexual harassment are the situations most likely to be perceived differently by men and women (Elkins and Velez-Castrillon 2008). In this ambiguous situation of stranger harassment, the gender difference is clear; men believed the target character to be more vain, less negative emotionally, more likely to react actively, and also more likely to think of the incident as harmless or a joke. Correlations between the men’s scores and their score on the Tolerance of Sexual Harassment Scale (Lott et al. 1982) suggest that men who are more tolerant of sexual harassment view the stranger harassment experience as eliciting less negative emotion, which would suggest that they believe that women enjoy these incidents. This assumption is qualified by the correlation between tolerance and self-blame, which suggests that these men believe that the woman is provoking or at least encouraging the harassing behavior. More research on men’s views of stranger harassment and their predictions of women’s responses is warranted by these results.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current study is a first step exploration of the effect of context on women’s perceptions of stranger harassment experiences. As a first step, it is limited in its scope and conclusions. While the vignettes were designed to evoke a generic and somewhat ambiguous stranger harassment experience, the results suggest that participants may have incorporated their own experiences and beliefs in their judgment of the story, especially the control condition. When this is taken with the participant recruitment process of self-selection, there is the possibility that more positive perceptions of stranger harassment were not found because it is possible that only the women with negative reactions completed the entire survey. Because of the ease of quitting a study administered via the internet, it is possible that women with more positive experiences were “turned off” and quit early on despite the care taken to hide the true purpose of the study and avoid the phrase “stranger harassment.” Unfortunately, we do not know the differences between the participants who completed the study and those who quit the study early. However, because the results found do mirror Fairchild and Rudman’s (2008) and Fairchild’s (2009) results, which were collected through more traditional (laboratory) methods, it would not be incorrect to assume that for the majority of women negative experiences will be most frequent. Future research may wish to incorporate longer vignettes that elaborate the details of the situation to ensure that all participants are evaluating the vignette similarly. Likewise, future research ought to solicit from participants information about their interpretation of the vignette; for example, asking participants if they have been in the same situation as the target character or know someone who has.

Another limitation of the current study is that each participant rated only one stranger harassment situation. The set-up did not allow for rating of multiple situations without the participant becoming highly aware of the hypotheses of the study. However, a creative solution that would allow a researcher to test multiple scenarios on the same participant would truly illuminate the differences between the context effects. Though not likely, there is a chance that the differences found between the vignettes is the result of some cohort effect of the group that responded to that vignette.

The results of the study highlight three major context factors that can alter the interpretation of the situation: attractiveness, age, and being alone or with friends. It is highly likely that these three factors (as well as others) may interact to influence a woman’s perception of any harassment experience. Future research should attempt to look at the factors in relation to each other as well as in conjunction with each other. For example, would a woman respond more positively to an older, attractive harasser when she is with friends as compared to a younger, unattractive harasser when she is alone? The combinations are many, but all of these factors are being assessed simultaneously by the victim. Moreover, the question arises as to which factor is most important. The sexual harassment literature has focused on attractiveness and severity. Are these the most important factors for stranger harassment situations, or might age and whether or not a woman is alone be more influential?

Moreover, because the study focused on perspective taking and did not assess women’s personal experiences, it is difficult to absolutely state that the perceived reactions and emotions are representative of how women actually interpret the situation in the moment. The research on perspective taking (Baston et al. 1997; Davis et. al. 1996) does give confidence in the results being representative of women’s personal reactions, especially when taken along with the fact that the perceived reactions found here mirror women’s actual reactions found by Fairchild and Rudman (2008). The important element, though, that is missing from this research through the perspective taking paradigm is the effect of characteristics of the target on perceptions of stranger harassment. While there is some evidence from the exploratory analyses with women’s own frequency of experience with stranger harassment as a target characteristic, this study does not account for target age, attractiveness, race, etc. Future research should investigate the characteristics of the target/victim as additional elements of the context.

The current study, additionally, focused solely on a heterosexual model in which females are the victim of men’s unwanted sexual attention. It is important to note that while concrete numbers on male victim-female harasser and same-sex stranger harassment are not available, anecdotal evidence suggests that these experiences do exist and it would be worthwhile to investigate how context may influence these situations. The literature on sexual harassment suggests that males are frequently the victim of sexual harassment in the workplace. Waldo et al. (1998) found that male-to-male sexual harassment was nearly as common in their samples as female-to-male harassment. In their study, Waldo and colleagues found that men were the victims of both unwanted sexual attention and gender harassment by women and men, but that the victims rated their experiences as only “slightly upsetting.” This suggests that the men may not view the behaviors addressed in the study as harassment. The most upsetting category to the men was gender harassment that enforced the male gender role. While stranger harassment has been defined in terms of behaviors that represent unwanted sexual attention (i.e., catcalls, whistles, stares), future research should expand this definition to include gender enforcing behaviors that may capture a broader range of gender policing that occurs in public spaces. It is likely that men are not only harassing women in public, but are also harassing their fellow men; moreover, there are likely men who experience being harassed by female strangers. Future research ought to vary the genders of the victim and perpetrator to assess stranger harassment from all angles.

Conclusion

This is the first research to suggest that when women are catcalled on the street they assess the context in formulating their reactions. Similar research from the field of sexual harassment supports such a conclusion. Many sexual harassment researchers have found that manipulating the context of the situation (i.e., attractive versus unattractive harasser) changes perceptions of the severity of the harassment. As highlighted throughout the Discussion section, there are a multitude of follow up studies that can elaborate the processes involved in these context effects. A more thorough understanding of the experiences and mental processes of women during stranger harassment situations can ultimately lead to programs for reducing its ill effects such as increased self-objectification and fear of rape (Fairchild and Rudman 2008).

Notes

It is important to note that most of the sexual harassment research focuses on the perception of harassment from the standpoint of an outside observer. The perceptions of outside observers of harassment have important legal ramifications for sexual harassers. It is the human resources department at a company or even a jury in a legal case that determine whether harassment has occurred and how it should be handled. While the victim needs to identify it as harassment to herself in order to file a complaint, it is the outside observer who has the power of instituting penalties for harassing behavior. Therefore, the sexual harassment literature focuses on understanding how observers interpret situations of sexual harassment. In the current investigation of context effects and stranger harassment, it is the victim’s perception that is sought through a perspective taking study because legal consequences are not typically a result of stranger harassment.

This presentation format has been shown by Granello and Weaton (2004) to be successful in attaining high completion rates. It is likely that more participants were retained in the current study by the use of a meter or gauge letting the participants know how many questions remained.

Due to an error in the survey administration, the severity/threat question did not appear for all participants. A total of 232 participants responded to the severity question. Importantly, no participants in trial 7 (Angie walking with two girlfriends) received the severity question.

The fear of harassment questions were not assessed for all male participants and thus removed from the analyses.

References

Baker, D. D., Terpstra, D. E., & Larntz, K. (1990). The influence of individual characteristics and severity of harassing behavior on reactions to sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 22(5–6), 305–325.

Baston, C. D., Early, S., & Salvarani, G. (1997). Perspective taking: Imagining how another feels versus imaging how you would feel. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23(7), 751–759.

Bowman, C. G. (1993). Street harassment and the informal ghettoization of women. Harvard Law Review, 106, 517–580.

Cartar, L., Hicks, M., & Slane, S. (1996). Women’s reactions to hypothetical male sexual touch as a function of initiator attractiveness and level of coercion. Sex Roles, 35(11/12), 737–750.

Davis, M. H., Conklin, L., Smith, A., & Luce, C. (1996). Effect of perspective taking on the cognitive representation of persons: A merging of self and other. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(4), 713–726.

Elkins, T. J., & Velez-Castrillon, S. (2008). Victims’ and observers’ perceptions of sexual harassment: Implications for employers’ legal risk in North America. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 19(8), 1435–1454.

Fairchild, K. (2009). Everyday stranger harassment: Frequency and consequences. Doctoral dissertation, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ.

Fairchild, K., & Rudman, L. A. (2008). Everyday stranger harassment and women’s objectification. Social Justice Research, 21(3), 338–357.

Faley, R. (1982). Sexual harassment: A critical review of legal cases with general principles and preventive measures. Personnel Psychology, 35, 583–600.

Fisher, B. S., & Sloan, J. J. (2003). Unraveling the fear of victimization among college women: Is the “shadow of sexual assault hypothesis” supported? Justice Quarterly, 20(3), 633–659.

Fitzgerald, L. F. (1990, March). Assessing strategies for coping with sexual harassment: A theoretical/empirical approach. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Association for Women in Psychology, Tempe, AZ.

Fitzgerald, L. F., Gelfand, M. J., Drasgow, F. (1995). Measuring sexual harassment: Theoretical and psychometric advances. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17(4), 425–445.

Golden, J. H., III, Johnson, C. A., & Lopez, R. A. (2001). Sexual harassment in the workplace: Exploring the effects of attractiveness on perception of harassment. Sex Roles, 45(11/12), 767–784.

Granello, D. H., & Wheaton, J. E. (2004). Online data collection: Strategies for research. Journal of Counseling and Development, 82, 387–393.

Grossman, A. J. (2008, May 14). Catcalling: Creepy or a compliment? Retrieved May 15, 2008, from http://www.cnn.com/2008/LIVING/personal/05/14/lw.catcalls/index.html.

Hickman, S. E., & Muehlenhard, C. L. (1997). College women’s fears and precautionary behaviors relating to acquaintance rape and stranger rape. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 527–547.

Katz, R. C., Hannon, R., & Whitten, L. (1996). Effects of gender and situation on the perception of sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 34(1/2), 35–42.

LaRocca, M. A., & Kromrey, J. D. (1999). The perception of sexual harassment in higher education: Impact of gender and attractiveness. Sex Roles, 40(11/12), 921–940.

Lott, B., Reilly, M. E., & Howard, D. (1982). Sexual assault and harassment: A campus community case study. Signs, 8, 296–319.

Netemeyer, R. G., Burton, S., & Lichtenstein, D. R. (1995). Trait aspects of vanity: Measurement and relevance to consumer behavior. Journal of Consumer Research, 21, 612–626.

Pryor, J. B. (1985). The lay person’s understanding of sexual harassment. Sex Roles, 13(5/6), 273–286.

Stop Street Harassment. (2009, September 11). A trip to the store. Retrieved September 22, 2009, from http://streetharassment.wordpress.com/2009/09/11/a-trip-to-the-store/.

Terpstra, D. E., & Baker, D. D. (1986). A framework for the study of sexual harassment. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 7(1), 17–34.

Trope, Y. (1986). Identification and inferential processes in dispositional attribution. Psychological Review, 93, 239–257.

Trope, Y., & Alfieri, T. (1997). Effortfulness and flexibility of dispositional judgment processes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 662–674.

Tuten, T. L., Urban, D. J., & Bosnjak, M. (2002). Internet surveys and data quality: A review. In B. Batinic, U. D. Reips, & M. Bosnjak (Eds.), Online social sciences (pp. 7–26). Seattle: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers.

Waldo, C. R., Berdahl, J. L., & Fitzegerald, L. F. (1998). Are men sexually harassed? If so, by whom? Law and Human Behavior, 22(1), 59–79.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fairchild, K. Context Effects on Women’s Perceptions of Stranger Harassment. Sexuality & Culture 14, 191–216 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-010-9070-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-010-9070-1