Abstract

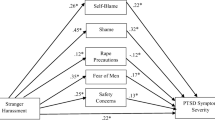

In the present research we explored how women are perceived as a function of their reactions to a harassing situation (piropo). Piropos, which are very common in Spain, are appearance-related comments directed by men to unknown women on the street. In Study 1, participants read hypothetical vignettes where a woman reacted positively, negatively, or indifferently (between-participants design) to a “mild/gallant” piropo. Men and women (n = 118) evaluated the competence, warmth, capacity for leadership, and superficiality/profoundness of the target of the piropo. Study 2 (n = 289) was similar to Study 1 (only with a within-participants design) and included additional dependent variables concerning the target’s likeability and participants’ intention to establish interpersonal relations with the woman in the scenario. Results showed that both male and female participants expressed less liking for the woman who reacted positively to the piropo as well as a lower intention to establish interpersonal relations with her; they also viewed this woman as less competent and more superficial. The relation between the woman’s reaction to the piropo and her likeability was mediated by the superficiality and competence with which she was perceived. The results of both studies revealed negative consequences for women who react positively to situations in which male strangers pay attention to their body. Policymakers, media, activists, and educators should be aware of how the conformity of women with traditional gender stereotypes--in this case feeling happy because they are valued by their physical appearance--can also have negative consequences for them similar to other hostile forms of stranger harassment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

According to a traditional conception of gender roles, women have appropriate characteristics for the relational domain but less suitable characteristics for more task-related domains (Fiske et al. 2007). Women’s physical appearance plays an important role in the relational domain, although empirical evidence shows that valuing women primarily because of their physical appearance leads to perceiving them as less competent, warm, human or moral, and lacking mental states (Heflick and Goldenberg 2009; Heflick et al. 2011; Loughnan et al. 2010). In all these studies, perceivers were instructed to focus on the appearance of women and then rate the target on several dimensions. However, we do not know if similar effects would have been found if instead of focusing on the appearance of women to get an impression of them, perceivers had observed women’s reactions to comments based on their physical appearance. These reactions of women may inform perceivers about whether or not women accept these traditional roles, which may somehow contribute to legitimizing perceptions in traditional gender terms.

The main goal of the present research was to analyze whether a woman who embraces her traditional role, in this case feeling happy after receiving a “mild/gallant” piropo (a type of street harassment), is seen as less competent--but warmer--and more superficial than a woman who feels upset about receiving the piropo. We also explore whether women’s reactions to a piropo influence the preference of participants--both men and women--to engage in meaningful relationships with them and whether this choice depends on the perceived competence and superficiality of such women.

Gender Stereotypes and Appearance

As part of gender stereotypes, there is a tendency for both men and women to mainly evaluate women--but not men--in physical terms instead of considering their personality or their achievements (Ellemers 2018). The theory that seems to have best analyzed the importance of physical appearance in traditional stereotypes about women is objectification theory (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). According to this theory, in Western culture women are seen as a body or a collection of body parts valued predominantly for their use by men, a process known as sexual objectification. This experience happens quite frequently in both interpersonal and social encounters and in audiovisual media. For instance, full-body image depictions of women in the media emphasize a stereotypical image of their bodies and facilitate their evaluation in terms of clothing and body shape (Matthews 2007)--a phenomenon termed bodyism (Unger and Crawford 1992). Additionally, when informing viewers about public figures, the media tend to focus on men’s accomplishments and emphasize women’s physical appearance or their personal life (Ellemers 2018).

As a result of these objectifying practices, women show greater levels of surveillance over their own body (Jackson and Chen 2015; Manago et al. 2015), get more involved in conversations about appearance (Jones and Crawford 2006), show greater sensitivity to appearance rejection than men (Park et al. 2009), and tend to base their self-esteem on appearance more than men do (Crocker et al. 2003; Moya-Garófano and Moya 2019). This tendency of girls and women to place excessive emphasis on their physical appearance is reflected for instance in the fact that, according to the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery (ISAPS 2017), women continued to drive the demand for cosmetic procedures in 2017, accounting for 86.2% of them, that is, 20,362,655 cosmetic procedures worldwide.

Research about sexism has also shown its relation with the importance of physical appearance for women. For instance, hostile sexism is positively correlated with the importance men place on women’s beauty, thinness, and overall attractiveness (Forbes et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2010), and men’s preference for attractive partners seems to be related to a dominance-based status-marker motive (Sibley and Overall 2011). Benevolent sexism also encourages women to adhere to their prescribed gender roles (Glick and Fiske 2001), among other things emphasizing their relational qualities and de-emphasizing their task-related characteristics (Barreto et al. 2010) and encouraging them to invest in their appearance (Mahalik et al. 2005) and use cosmetics (Forbes et al. 2004; Franzoi 2001). Consistent with these attitudes, women can even experience an increase in their self-esteem or feel empowered when they attract men’s sexual attention through their physical appearance (Liss et al. 2011; Nowatzki and Morry 2009). This positivity is in line with the phenomenon of enjoyment of sexualization, which happens when women find sexual attention based on their appearance pleasing and experience some sort of empowerment as a result (Liss et al. 2011).

Consequently, women who behave in accordance with what traditional gender stereotypes prescribe about physical appearance may be perceived as having other characteristics traditionally associated to them, such as communion (Haines et al. 2016). As research has shown, when an aspect or component of a stereotype is activated, it becomes easier to activate other components as well (Fiske and Taylor 2017). Thus, homemakers are usually perceived as warm but not competent outside the home, generating the “women are wonderful” effect (i.e., positive ratings of women primarily based on communal qualities; Eagly and Mladinic 1989). Women’s physical appearance also elicits specific associations in perceivers. For instance, women tend to be judged more negatively by both men and women when wearing provocative compared to conservative clothing (Abbey et al. 1987; Cahoon and Edmonds 1989) and to be perceived as more qualified for secretarial rather than managerial roles when they look sexy (Glick et al. 2005; Wookey et al. 2009).

Even dehumanization may be a negative consequence of appearance-related evaluations of women. In fact, several studies support the idea that objectified targets are to some extent dehumanized. Heflick and Goldenberg (2009) found that focusing on a female target’s appearance reduced the degree to which she was perceived as having characteristics typifying human nature. Similarly, sexualized models are perceived as being mindless (Loughnan et al. 2010), and sexualized images of women have been found to activate regions of the brain responsible for object usage--although only among male participants and especially those high in hostile sexism (Cikara et al. 2011). Heflick et al. (2011) further found that focusing on women’s--but not men’s--appearance led to their objectification and thus reduced their perceived warmth, morality, and competence; these effects were independent of women’s race/ethnicity, familiarity, physical attractiveness, and occupational status.

Stranger Harassment and Piropos

Stranger harassment has been defined as the “[sexual] harassment of women in public places by men who are strangers” (Bowman 1993, p. 519), and it “includes both verbal and nonverbal behaviors, such as wolf-whistles, leers, winks, grabs, pinches, catcalls, and stranger remarks; the remarks are frequently sexual in nature and comment evaluatively on a woman’s physical appearance or on her presence in public” (Bowman 1993, p. 523). Stranger harassment is perpetrated by men who are not known to the victim (i.e., not a co-worker, friend, family member, or acquaintance), and it occurs in public places (Fairchild and Rudman 2008). Although women perceive most stranger harassment situations negatively, there are circumstances in which at least some women perceive them positively. This is the case with some kinds of piropos.

Piropos are examples of stranger harassment that are typical in Spain yet also present in many countries with a Mediterranean culture and other Spanish-speaking countries (Fridlizius 2009). A piropo is “a short saying that praises a quality of someone, especially the beauty of a woman” (Real Academia Española [Royal Spanish Academy] 2019a). Piropos can vary in valence; some piropos are undoubtedly labeled as rude and lewd, but others are considered pleasant and even flattering (Moya-Garófano et al. 2019; Moya-Garófano et al. 2018). In the present research we explored the latter type. Although some people call for forbidding any kind of piropos, arguing that they are “an invasion of women’s privacy” (“La presidenta,” 2015, para. 2), others consider that some piropos can be pleasant and enjoyable, such as the “mild/gallant” ones which “try to attract women’s attention in order to court them or win their love” (Ferreras 2015, para. 1) and therefore should not be considered negative or be banned (Sust 2015, para. 5-6).

Stranger harassment and piropos are prototypical examples of objectifying situations and reflect gender stereotypes. When expressing a piropo, men treat women basically according to their physical appearance, presumably with some of the consequences we mentioned. Moreover, the positive appearance of a “gallant” or “mild” piropo can make it especially harmful, as shown by the literature on benevolent forms of sexism: Benevolent behaviors are less likely to be perceived as expressing prejudice (Barreto and Ellemers 2005), but despite their positive tone they still contribute to perpetuating the subordinate status of the recipient (Glick and Fiske 2001; Moya et al. 2007).

The Current Research

In two studies we presented Spanish participants (men and women) with a scenario in which a woman reacted in three different ways to a “mild/gallant” piropo: positively (with happiness), negatively (with anger), or indifferently. The following piropo was used: “Giiiirl, be careful because chocolates melt in the sun.” A previous study (Moya-Garófano et al. 2019) found that this piropo was perceived by female college students as slightly objectifying: on a four-item scale with answers ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (completely) (e.g., “It treats the woman as an object, not a person”, higher scores indicating higher objectification), the mean was 3.26; and it was assessed as moderately positive: on a two-item scale with answers ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (completely) (e.g., “expresses a positive image of the woman”, higher scores indicating a more positive view of women), the mean was 4.66. People who advocate the use of piropos usually insist on differentiating between the “lewd” or unpleasant ones, which are not well received, and the “mild/gallant” ones, which should be welcomed (Ferreras 2015). The target women in the scenarios of our studies reacted to this second type of piropo because we considered that it would be more credible for participants to expect different types of reactions toward this kind of piropo than toward a ruder one, which usually elicits negative reactions.

Our first hypothesis is related to different dimensions in the perception of women depending on their reactions to the piropo. We asked participants to express their assessments of these women in terms of competence and warmth (Studies 1 and 2), leadership (Study 1), and superficiality/profoundness (Studies 1 and 2). The main idea behind our first hypothesis was that the woman who reacted with happiness when receiving a mild comment would be perceived as less competent and with less capacity of leadership, as well as more sociable and superficial--because she was the woman who best reflected gender stereotypes. Specifically, regarding competence, we hypothesized that the target woman who felt good when receiving a “mild/gallant” piropo would be perceived as less competent than the woman who felt badly because competence is not associated with a traditional stereotype of women (Hypothesis 1a) (Ellemers 2018; Fiske et al. 2002). In this regard, Rudman and Borgida (1995) found that men considered women to be less competent after having just been exposed to a sexualized image of another woman, and Heflick and coworkers (Heflick and Goldenberg 2009; Heflick et al. 2011) found evidence that men and women focusing on the physical appearance of a woman--versus focusing on her as a person--perceived her as having a lower level of competence.

Warmth is a trait that is associated with traditional women so we expected that a target woman who reacts positively to the piropo will be perceived as being more sociable than a woman who reacts with displeasure (Fiske et al. 2002) (Hypothesis 1b). In research about confronting sexism--of which stranger harassment is clearly an expression--women who confront others are perceived as difficult people who react disproportionately or are regarded as whiny, hypersensitive, and cold at the interpersonal level (Becker et al. 2014; Czopp and Monteith 2003; Dodd et al. 2001). Confronters are also often considered impolite and aggressive (Swim and Hyers 1999). These perceptions may even increase when the sexist comment appears to be a compliment (Becker et al. 2011).

In terms of the capacity for leadership, we hypothesized that a target woman who felt good after such a piropo would be perceived as having less capacity for leadership than a woman who reacted with anger or indifference (Hypothesis 1c). According to the role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders (Eagly and Karau 2002), when women adhere to feminine stereotypes—in our research this would apply to the woman who happily accepts the piropo—they are perceived as weak leaders.

We included a new dimension to measure the impression of women based on their reaction to a piropo: profoundness/superficiality. According to the Real Academia Española [Royal Spanish Academy] (2019b), superficial [superficial] refers to “apparent, without soundness or substance; frivolous, without basis,” whereas someone who is profound [profundo] is someone “of a penetrating or profound understanding” (Real Academia Española 2019c). The meanings of the adjectives superficial and profound are quite similar in English and Spanish, according to the Oxford English Dictionary: Superficial: “lacking depth of character or understanding” ( n.d.); profound: [of a person or statement] “having or showing great knowledge or insight” ( n.d.). We thus regard profoundness and superficiality as endpoints on a single continuum.

In everyday parlance in Spain, it is very common to hear expressions about whether a person is more or less superficial--profound, however, is used less. Still, this continuum seems to capture a trait considered uniquely human (Haslam and Loughnan 2014). Research has shown that sexually objectified women are dehumanized by both men and women (Vaes et al. 2011), that objectification causes women to be perceived as less fully human (Heflick and Goldenberg 2009), and that objectified women are attributed less mind and accorded lesser moral status than non-objectified women (Loughnan et al. 2010). Therefore, Hypothesis 1d predicted that a target woman who felt happy after hearing a piropo (i.e., who was believed to embrace her traditional and objectifying role) would be perceived as being more superficial--with less profoundness--than a woman who reacted with anger (i.e., a response that is counter to traditional femininity).

Our second hypothesis, which we tested in Study 2, was related to women’s likeability and participants’ preference for sharing activities or engaging in relationships with them as a function of their reactions to the piropo. We expected participants’ judgments of likeability to be lower for the target woman who reacted happily (Hypothesis 2a). We also expected participants to report less preference for interacting or establishing significant social relationships with this target woman (Hypothesis 2b). However, we expected the woman who reacted with happiness to the piropo to be selected as often by participants when they were asked about their willingness to engage in a superficial relationship with her (Prediction 2c). We based this hypothesis on previous research that has shown a negative view of objectified and sexualized women (Cikara et al. 2011; Heflick and Goldenberg 2009; Infanger et al. 2016).

Our third hypothesis referred to some variables that may explain the relation between women’s reaction to the piropo and their likeability. We expected perceptions of competence (Hypothesis 3a) and superficiality (Hypothesis 3b) to mediate the relation between women’s reaction and their likeability and selection for meaningful relationships. Specifically, we expected the target who reacted with happiness to be less liked and chosen for meaningful relationships than the other two targets because the former would be perceived as less competent and more superficial. Regarding superficiality, this hypothesis was based on the fact that, according to studies conducted with U.S. undergraduates and samples from 37 countries, the most valuable characteristics of a heterosexual partner were dependable character, emotional stability/maturity, and a pleasing disposition (Buss et al. 1990; Buss et al. 2001). We also considered that competence would be valued in meaningful relationships because, although it is sometimes emphasized that men value physical appearance (i.e., “good looks”) more than women regarding mate preference, this characteristic is ranked, even by men, as less important than others that are more related to competence--such as education and intelligence (Buss et al. 1990, 2001).

Concerning the influence of participants’ gender on the perception of a target, we expected the following: Given that our female participants were assessing ingroup targets, the ingroup favoritism trend would lead to a more positive view of women in general, seeing them as being more competent and warm, having more leadership abilities, and being less superficial than men (Tajfel and Turner 1979). However, we did not expect to find an interaction between participants’ gender and their perceptions and evaluations of the target women depending on their reactions to the piropo. To the extent that both men and women might have an objectifying and traditional view of women, we did not expect their views about a woman who reacted positively to a piropo to differ.

We tested Hypotheses 1a, 1b, and 1d both in Studies 1 and 2, and Hypothesis 1c only in Study 1. We tested Hypotheses 2 and 3 in Study 2. In both studies, a neutral condition was added, with the aim of analyzing how a woman who reacted with indifference was evaluated in the different measures included. Comparisons with this neutral condition allowed us to infer whether the perceptions of the participants were guided by the woman who reacted with happiness or by the woman who reacted with anger. Our prediction was that the main differences would appear between the condition in which the woman experienced happiness after receiving the piropo and the other two conditions because the happiness condition was the situation that clearly reflected women’s traditional gender roles. The data files for Studies 1 and 2 are publicly available at https://osf.io/sn3j7/.

Study 1

Method

Participants

A total of 118 first-year students (Mage = 19.81, SD = 2.91, range = 18-38) at a university in the south of Spain--mostly women (n = 94, 79.7%)--participated in the study. Based on this sample size, the sensitivity analysis indicated a sensitivity to detect an effect size of ηp2 = .07, with 80% power and alpha equal to .05. The present study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Granada Ethics Committee for studies involving human participants.

Procedure

The study was conducted in Spanish wherein students completed a paper-and-pencil booklet in exchange for course credit. In the present study we used an experimental between-participants design with one independent variable, that is, the three conditions regarding the reactions of the target woman when exposed to a piropo (happiness or anger or indifference). Participants were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions. In all the groups, participants imagined what was described in the following scenario:

Lucía is walking along the street alone. She is walking briskly and thinking to herself, without paying too much attention to what is going on around her. When she crosses the road, she realizes that she is about to pass by a square where a group of young guys are sitting on a bench and looking at her. She continues walking and passes by without looking at them or paying attention to what they are doing. Then, as she is passing, one raises his voice and says to her:

“Giiiirl, be careful because chocolates melt in the sun.”

Until this point, the scenario was identical in the three conditions; next, the booklet included a brief paragraph describing the reaction of the woman (Lucía) to the piropo. (a) In the happiness condition the description read: “The girl feels good when she hears the piropo because it brings her happiness and optimism and increases her self-esteem. Far from irritating or bothering her, the piropo improves her mood.” (b) In the anger condition the description read: “The girl feels bad when she hears the piropo because it makes her angry, irritated and annoyed. Far from feeling happy, the piropo makes her feel undervalued and puts her in a bad mood.” (c) In the indifference condition the description was: “The girl is neither happy nor angry about the piropo; it simply does not elicit any emotion or special reaction in her. Her reaction is indifference.” (The scenarios are available in their original Spanish in the online supplement.)

Measures

After reading the scenario, participants expressed their impressions on a Likert answer scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (totally agree) about the woman along the following dimensions and in the following order.

Competence and Warmth

Three descriptors were used to measure competence (competent, intelligent, capable) (α = .83) following Heflick and Goldenberg (2009), who used these items with U.S. undergraduates, obtaining a similar reliability (α = .88). Four items were used to measure warmth (attentive, romantic, affectionate, warm) (α = .79). Three of them had been used by Barreto et al. (2010) with a Dutch sample; we added an additional item (affectionate) to increase the reliability found in the research by Barreto et al. (α = .38). Responses across items were averaged so that higher scores indicated higher competence and warmth.

Leadership

Six items measured the perceived capacity for leadership of the character in the vignette, inspired by the Affective-Identity measure of the Motivation to Lead Subscale (Chan and Drasgow 2001) (α = .75). Some examples of these items are: “If she were a university student, she would be a good student representative” and “If she worked in a company, she would be able to perform perfectly in an executive position.” The original scale has nine items and was designed to be answered in the first person. It has been validated with Singapore military and students and with U.S. students, showing high reliability coefficients (from .84 to .91). (The six items we used are available in the online supplement in both English and Spanish.)

Profoundness/Superficiality

To measure this dimension, we previously conducted a pilot study that allowed us to identify some traits of the superficiality-profoundness dimension. A total of 55 first-year students at a university in the south of Spain (n = 40, 72.7% women) evaluated 10 items about behaviors, habits, and interests as features of a superficial or a profound person on a scale from 1 (superficial) to 7 (profound). No gender differences were found in the item ratings. Four items were associated with the superficial pole (scoring significantly below the scale’s midpoint): “Would like to get married, have children, and stop working” (M = 3.30, SD = 1.74); “Enjoys going shopping” (M = 2.93, SD = 1.55); “Likes to talk about superficial topics with some friends” (M = 2.90, SD = 1.74); and “Likes to watch reality shows on TV” (M = 2.57, SD = 1.39). Six items were associated with the profound pole (scoring significantly above the scale’s midpoint): “Likes to watch the news on TV” (M = 4.63, SD = 1.65); “One of the things she values most about her job are the relationships with colleagues” (M = 5.37, SD = 1.25); “Enjoys reading good literature” (M = 5.02, SD = 1.69); “Has many professional aspirations” (M = 5.18, SD = 1.27); “Likes to talk about profound topics that concern their ideas and feelings” (M = 5.89, SD = 1.31); “Is very concerned with the political situation of our country” (M = 5.59, SD = 1.31). (The Spanish versions of these items can be found in the online supplement.)

In Study 1 participants expressed to what extent each of these ten characteristics could be attributed to the woman in the scenario. To simplify the analyses, the six items concerning profoundness were inverted, and the average of the ten items was calculated so that higher scores indicated that the person was perceived as being more superficial (α = .81).

In another study with a within-participants design, a total of 172 college students, mostly women (n = 133, 77.3%), evaluated two target women (the order of presentation was randomized). The description of one was based on the items considered representative of profoundness, whereas the description of the other was based on the items considered superficial. The item to evaluate both women was: “What type of impression do you have of this woman,” rated from 1 (very negative) to 7 (very positive). Mean scores showed that the superficial woman was evaluated more negatively (M = 3.16, SD = 1.34) than the profound one (M = 6.07, SD = 1.06), F(1,171) = 515.11, p < .001, ηp2 = .75.

Sociodemographic Data

Finally, participants provided information about their gender, age, and the degree that they were pursuing.

Results

Participants’ ratings about how they perceived women in terms of competence, warmth, leadership skills, and profoundness/superficiality were submitted to four separate 3 (Target Woman’s Reaction to the Piropo: happiness, anger, indifference) × 2 (Participant Gender) ANOVAs. Descriptive statistics are shown on Table 1. We also analyzed patterns of missing data for each variable. There was one missing value only in two items (in the scale about superficiality), representing .8% of the cases. A scale average was calculated for these participants, excluding the missing variable; we repeated all the subsequent analyses using multiple data imputation for missing values and the results were identical.

Regarding the competence measure, the effect of the experimental manipulation was significant, F(2, 112) = 4.85, p = .01, ηp2 = .08, confirming Hypothesis 1a. Post-hoc Bonferroni-corrected tests revealed that the woman in the happiness reaction condition was perceived as significantly less competent than the woman in the anger (p = .011, d = .64) and indifference (p = .027, d = .61) conditions; women in the last two conditions did not differ (p = .668, d = .07). In terms of warmth (p = .703) and the capacity for leadership (p = .505), the main effect of the experimental manipulation was not significant. Therefore, neither Hypothesis 1b nor Hypothesis 1c were confirmed in Study 1. Competence and warmth scores were positively correlated (r = .42, p < .001).

Concerning superficiality, we found a main effect of the experimental manipulation of the target woman’s reaction to the piropo, F(2, 112) = 15.07, p < .001, ηp2 = .21. Post-hoc Bonferroni-corrected tests revealed that the woman in the happiness reaction condition was perceived as being significantly more superficial than the woman in the anger (p < .001, d = 1.28) and indifference (p < .001, d = 1.05) conditions, confirming Hypothesis 1d. Perceptions of the women in the last two conditions did not differ significantly (p = .547, d = .35).

Regarding participants’ gender, no difference was found in the competence dimension, F(1, 112) = 3.53, p = .06, ηp2 = .03, (Mmen = 4.47, SD = 1.00; Mwomen = 4.80, SD = 1.04). A significant main effect was found in the superficiality dimension, F(2, 112) = 4.61, p = .03, ηp2 = .04: Male participants considered the female target as being more superficial (M = 3.99, SD = .80) than did female participants (M = 3.76, SD = .85). No significant interactions between gender and condition were found for any of the dependent measures analyzed.

Discussion

As predicted, results showed that the reactions of the woman in the vignette to the piropo affected how participants perceived her in terms of competence and profoundness/superficiality. When the woman was happy after receiving the piropo, she was viewed as less competent and more superficial than when she reacted with anger or indifference. We did not find the expected effect of perceiving woman who reacted with happiness as being warmer. However, it is important to note that scores in competence and warmth were positively correlated, showing that competence and warmth were not orthogonal or antagonistic traits in this case (Abele and Wojciszke 2014). In addition, the fact that perceptions of women who reacted with anger and indifference did not differ in competence and superficiality suggests that the effects found in Study 1 were mainly driven by the perception of the women who reacted with happiness.

Study 2

After obtaining some evidence that the reaction of women who are the target of a piropo has an impact on the way they are perceived by others, we conducted a second study with the following goals: (a) to replicate the results of Study 1 (Hypothesis 1) using a within-participants design, which minimizes the influence of participants’ individual differences; (b) to analyze whether the target woman’s reactions to the piropo affected her likeability and selection for meaningful social relationships (Hypothesis 2); and (c) to test if this likeability and selection were mediated by her perceived competence and superficiality (Hypothesis 3). Because of the unbalanced gender composition of the sample in the first study, we recruited a larger number of men. The scenario of Study 1 was also used in the present study. Study 2 was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Granada Ethics Committee for studies involving human participants. The data file for Study 2 is publicly available at https://osf.io/sn3j7/.

The design was a within-participants design with just one independent variable with three levels (i.e., we asked participants to imagine three different women who each reacted differently to the piropo: with happiness, anger, or indifference). Perceptions of each target woman in terms of competence, warmth, and superficiality were measured. The likeability and selection of each of target for meaningful and less meaningful activities were also measured.

Method

Participants

A total of 290 college students at a university in the south of Spain (Mage = 19.42, SD = 2.37, range = 17-34)--174 men (60.2%) and 115 women (39.8%)--participated in the study. One participant did not report his/her gender and was eliminated. Based on this sample size, the sensitivity analysis indicated a sensitivity to detect an effect size of ηp2 = .01, with 80% power and alpha equal to .05.

Procedure

The study was conducted in Spanish wherein students completed a questionnaire in exchange for course credit. They received a web link to answer the online questionnaire; a code guaranteed their anonymity and made it possible to reward them with course credit. In all the groups, participants imagined what was being described in the scenario: a woman receives a piropo on the street (“Giiiirl, be careful because chocolates melt in the sun”).

Given the within-participants design, we asked participants to imagine three different women: Ana, Lucía, and María, each one reacting in a different way to the piropo. First, we presented Ana’s reaction to the piropo, then Lucía’s reaction, and finally María’s reaction. The order of presentation of the three reactions of the women was counterbalanced. Thus, we created three conditions that differed in the order of presentation to ensure that it did not affect participants’ responses. The order was: (a) happiness-anger-indifference; (b) anger-indifference-happiness; and (c) indifference-happiness-anger. The names of the women remained in the same order regardless of the condition: Ana was always in the first place, Lucía was the second one, and María appeared in the third place. Thus, the three women experienced the three possible reactions.

Measures

After being presented with each reaction, participants answered the following questions about their impression of the target woman. The measures of competence and warmth were the same as in Study 1. Cronbach’s alphas were all acceptable: Competence (α = .87 for happiness, α = .87 for anger, α = .85 for indifference) and warmth (α = .77 for happiness, α = .77 for anger, α = .78 for indifference). Except when otherwise specified, the measures used a scale that ranged from 1(strongly disagree) to 7 (totally agree).

Profoundness/Superficiality

To confirm the findings of Study 1 with a different measure of profoundness/superficiality, we included 14 items from a previous pilot study that analyzed the assessment of a series of characteristics and preferences as superficial or profound. Because we are not aware of any previous studies that have measured this construct in the perception of people (except for some studies in which maturity has been explored; Buss et al. 2001), we decided to measure it in a different way from Study 1. If the results were similar, the attribution of the findings to the specific measure used would lose strength.

In the pilot study, a total of 172 first-year students at a university in the south of Spain (n = 133, 77.3% women) completed a questionnaire about 14 behaviors, habits, and interests, evaluating each one as characteristic of a superficial person (1) or a profound person (7). We found no gender differences. There were significant differences from the scale’s midpoint (using the one-sample t-test) for all the items. Eight items were associated with the superficial pole: “Gives a lot of importance to appearance” (M = 1.99, SD = 1.08); “Loves brands and expensive things” (M = 1.89, SD = 1.07); “Shows lack of reflection and profoundness of thought” (M = 2.19, SD = 1.54); “Judges people on initial impressions” (M = 1.79, SD = .98); “Has little ability to analyze situations that occur to her/him” (M = 2.35, SD = 1.12); “Is immature” (M = 2.33, SD = 1.11); “Has little interest in other people’s feelings” (M = 2.15, SD = 1.18), and “Having a lot of money is her/his priority in life” (M = 2.30, SD = 1.12). Six items were associated with the profound end: “Likes to read and to find out about current issues” (M = 6.0, SD = .96); “Attempts to understand what she/feels and what other people feel” (M = 6.18, SD = .98); “Is sensible, prudent” (M = 5.4, SD = 1.03); “Is interested in meeting people regardless of their aspect” (M = 6.24, SD = .95); “Is critical” (M = 5.38, SD = 1.53); “Has the ability to assess people beyond their appearance” (M = 6.28, SD = .84). (The Spanish versions of these items can be found in the online supplement.)

In Study 2 the eight items concerning profoundness were inverted, and we computed an averaged overall score in which higher scores indicated that the person was perceived as being more superficial. Alpha coefficients for the three conditions were: α = .82 (happiness), α = .86 (anger), α = .80 (indifference).

Likeability

We used a four-item scale to measure the likeability of the female target: (a) “What impression do you have of this person?” [“¿Qué impresión te ha causado esta persona?”] (1, very negative; 7, very positive); (b) “How much do you think you would like this person?”[“¿Qué estima crees que le tendrías a esta persona?”] (1, very little; 7, very much); (c) “How important do you think that a person like this would be in your life?” [“¿Cómo de importante crees que sería una persona así en tu vida?”] (1, very unimportant; 7, very important); and (d) “To what extent would you want to be like this person?” [“¿En qué medida te gustaría parecerte a esta persona?”] (1, not at all; 7, very much). Alpha coefficients for the likeability measure in the three experimental conditions were: α = .87 (happiness), α = .90 (anger), α = .84 (indifference). Responses were averaged to compute the likeability index so that higher scores indicated a higher likeability.

Activities Participants Would Like to Share with the Target Woman

Finally, participants read a list of 10 items that represented different types of activities or roles. They scored the probability with which they would like to take part in each of them with the target woman described using a Likert-type response scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 7 (completely). Five of the items were concerned with meaningful aspects related to the personal realm and can be considered highly relevant for one’s personal life and well-being (e.g., “Being your best friend”; “Being your emotional support”). (All items, in both the original Spanish and in English, are available in the online supplement.) Alpha coefficients in the three conditions related to relevant activities for one’s personal life were: α = .91 (happiness), α = .91(anger), α = .85 (indifference).

The other five activities and roles were related to more mundane activities of everyday life--more superficial and less relevant (e.g., “Talking to you while in line at the supermarket”; “Being your instructor at the gym”). Alpha coefficients for this index were: α = .85 (happiness), α = .82 (anger), α = .82 (indifference). Responses for both subscales (i.e., meaningful and everyday) were averaged to develop two indices reflecting the preference for sharing relevant and superficial activities with the target woman, so that higher scores indicated higher preference for sharing the activities.

Sociodemographic Information

Finally, information about participants’ gender, age, and the degree that was being pursued was requested.

Results

All the dependent variables were analyzed using a mixed 3 × 2 ANOVA with the condition of Woman’s Reaction to the Piropo (reactions of happiness, anger, and indifference) as a repeated-measure factor and Participant Gender as a between-participants factor. We performed pairwise comparisons using a Bonferroni correction and included the order of presentation of the three women’ s reactions as a covariate. We also analyzed patterns of missing data for each variable. There were missing values in only seven items, representing 2.4% of the cases. No item had more than 1% of missing values. We calculated a scale average for these participants, excluding the missing variable; we repeated all subsequent analyses using multiple data imputation for missing values and the results were identical.

Perceived Competence, Warmth, and Superficiality

The hypotheses concerning these perceptions were mainly confirmed (see Table 2 for relevant statistics). Regarding competence, the main effect of condition was found to be significant, F(2, 284) = 9.87, p < .001, ηp2 = .065: The woman who reacted with happiness (M = 4.00, SD = 1.31) was perceived as being significantly less competent than the woman who reacted with anger (M = 4.90, SD = 1.23, p < .001, d = .49) and indifference (M = 5.04, SD = 1.17, p < .001, d = .71), confirming Hypothesis 1a. The perceived competence of the last two target women did not differ (p = .282, d = .11). The main effect of participants’ gender was also significant, F(1, 285) = 16.53, p < .001, ηp2 = .055, with female participants (M = 4.80, SE = .08) rating the target woman as being more competent than did male participants (M = 4.48, SE = .07). The interaction between participants’ gender and the repeated measure of women’s reaction to the piropo was not significant, F(2, 284) = .97, p = .379, ηp2 = .007.

In terms of perceived warmth, there was a significant main effect of experimental condition, F(2, 284) = 5.93, p = .003, ηp2 = .04. However, the woman who reacted happily to the piropo was perceived as being warmer (M = 4.49, SD = 1.21) only in comparison to the woman who reacted with indifference (M = 4.32, SD = 1.16, p = .022, d = .12). There was no significant difference when comparing women in the happiness and anger conditions (M = 4.32, SD = 1.08, p = .067, d = .11); perceptions of targets in the anger and indifference conditions also did not differ significantly (p = .997, d = 0). The main effect of participants’ gender indicated that female participants (M = 4.57, SE = .08) rated the target woman as warmer than male participants did (M = 4.25, SE = .06), F(1, 285) = 9.92, p = .002, ηp2 = .03. The interaction between participants’ gender and the woman’s reaction was significant, F(2, 284) = 3.12, p = .045, \( {\upeta}_{\mathrm{p}}^2 \) = .02. Women, in comparison to men, rated the woman who reacted with happiness as warmer, t(287) = −3.95, p < .001; however, women and men did not differ in how they perceived the woman in terms of sociability when she responded with anger, t(287) = −1.39, p = .167, or with indifference, t(287) = −1.54, p = .125. Competence and warmth scores were positively correlated (r = .69, p < .001 in the happiness condition; r = .72; p < .001 in the anger condition; and r = .66, p < .001 in the indifference condition).

Concerning superficiality, Hypothesis 1d was also confirmed, F(2, 284) = 18.75, p < .001, ηp2 = .12: The woman who reacted with happiness (M = 4.23, SD = .81) was perceived as more superficial than the one who reacted with anger (M = 3.25, SD = .90, p < .001, d = .72) or with indifference (M = 3.33, SD = .73, p < .001, d = .78); women in the last two conditions did not significantly differ in how superficial they were perceived to be (p = .223, d = .08). Regarding participants’ gender, the difference was not significant, F(1, 285) = 3.27, p = .072, ηp2 = .011 (Mwomen = 3.55, SE = .04; Mmen = 3.65, SE = .03). However, the interaction between participants’ gender and target reaction to the piropo was significant, F(2, 284) = 6.75, p = .001, ηp2 = .045. There was no difference between male and female participants when they judged the superficiality of the target woman who reacted with indifference, t(287) = 1.24, p = .215; however, female participants rated the woman who reacted with happiness as being more superficial than male participants did, t(287) = −2.25, p = .025, and male participants rated the woman who reacted with anger as being more superficial than female participants, t(287) = 3.80, p < .001 (see Table 2).

Likeability and Preference for Sharing Activities

Hypotheses concerning these aspects were mainly confirmed (see Table 2 for relevant statistics). The results supported Hypothesis 2a because the likeability of the woman depicted in the scenario was dependent on her reaction to the piropo, F(2, 284) = 15.22, p < .001, ηp2 = .097. Participants liked the woman who reacted with happiness (M = 3.6, SD = 1.29) less than the one who reacted with anger (M = 4.33, SD = 1.33, p < .001, d = .36) and the one who reacted with indifference (M = 4.75, SD = 1.16, p < .001, d = .69); participants also liked the woman who reacted with anger less than the one who reacted with indifference (p < .001, d = .24). There was also a main effect of participants’ gender, F(1, 285) = 8.14, p = .005, ηp2 = .028: Female participants (M = 4.38, SE = .07) liked the targets more than men did (M = 4.13, SE = .06). The Participant Gender x Woman’s Reaction interaction was not significant, F(2, 284) = 2.47, p = .087, ηp2 = .017.

We also found a significant influence of target’s reactions on the participants’ preferences to interact with her for personally meaningful activities or tasks (e.g., best friend), F(2, 284) = 11.96, p < .001, ηp2 = .08, confirming Hypothesis 2b. The woman who reacted with happiness (M = 3.44, SD = 1.35) was clearly less preferred than the one who reacted with anger (M = 4.28, SD = 1.28, p < .001, d = .42), and the one who reacted with indifference (M = 4.26, SD = 1.14, p < .001, d = .51); no differences were found in the preferences showed by the participants for the woman in the anger condition in relation to the indifference condition (p = .711, d = .01). In this case, female participants also scored (M = 4.24, SE = .07) higher than male participants (M = 3.83, SE = .06), F(1, 285) = 18.94, p < .001, ηp2 = .06. The Gender x Condition interaction was significant, F(2, 284) = 3.55, p = .03, \( {\upeta}_{\mathrm{p}}^2 \) = .024. There was no difference between male and female participants in their preference for meaningful relationships with the woman who reacted with happiness, t(287) = −.53, p = .17 p = .594; however, female participants liked the woman who reacted with anger, t(287) = −4.63, p < .001, and also the woman who reacted with indifference, t(287) = −3.58, p < .001, more than male participants did.

Finally, in the case of everyday activities (e.g., “Talking to you while in line at the supermarket”), there was no main effect of condition, F(2, 284) = 1.99, p = .139, ηp2 = .014, in line with Prediction 2c. However, there was a difference according to participants’ gender: Female participants scored (M = 4.57, SE = .08) higher than male participants (M = 3.94, SE = .06), F(1, 285) = 39.63, p < .001, \( {\upeta}_{\mathrm{p}}^2 \) = .122. The interaction between participants’ gender and women’s reaction was not significant, F(2, 284) = .54, p = .584, ηp2 = .004.

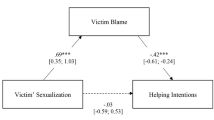

Mediation Analysis

According to our third hypothesis, the relation between target women’s reaction to the piropo and their likeability and selection for meaningful relationships by participants was expected to be mediated by competence (Hypothesis 3a) and superficiality (Hypothesis 3b). We used the MEMORE macro (Montoya and Hayes 2017), which estimates the total, direct, and indirect effects for within-subjects designs following the methodology proposed by Judd et al. (2001). This macro has the advantage of exploring the indirect effect of each mediator while controlling for the indirect effects of the others. This procedure is ideal in cases where mediating variables may potentially be correlated with each other. MEMORE also allows the size of indirect effects to be directly compared, which provides insight regarding which mechanisms have the strongest influence on the dependent variable (Montoya and Hayes 2017).

We conducted two different analyses with the MEMORE macro, one with likeability and the other with selection for meaningful relationships as dependent variables; the mediators--perceived competence and superficiality--were included in parallel in both analyses. Because the anger and indifference conditions were not significantly different in the ANOVAs (except for likeability), we decided to group the scores on these variables. The number of samples for Monte Carlo confidence intervals was 10,000, the level of confidence for all confidence intervals in the output was 95%, and an effect is considered significant when the confidence interval does not span across zero. The order of presentation of the three women’ s reactions was included as a covariate.

As regards the likeability of the target woman who reacted with happiness (coded 0) and the other two target women (coded 1) (who reacted with anger and indifference), the indirect effect was significant for superficiality (.74, 95% CI [.91, .58]) and competence (.35, 95% CI [.47, .23]). Pairwise comparisons between both indirect effects showed that superficiality significantly differed from competence (-.39, 95% CI [-.16, -.64]). The same pattern of results was found for preference for meaningful relationships: the indirect effect was .43 (95% CI [.54, .33]) for superficiality and .16 (95% CI [.24, 09]) for competence; pairwise comparisons between both indirect effects showed that superficiality significantly differed from competence (-.27, 95% CI [-.11, -.43]). See Fig. 1 for diagrams of these mediation models.

Discussion

The results of Study 2 replicated those of Study 1 concerning perceived competence and superficiality, this time using a within-participants design: The target woman who reacted with happiness to a piropo was seen as less competent and more superficial than the target women who reacted with anger or indifference. Moreover, in Study 2 participants perceived the woman who reacted with happiness to the piropo as being warmer only compared to the woman who reacted with indifference. The reactions of women receiving a piropo influenced not only the impression that they caused but also their likeability and the type of interpersonal relationship that observers would like to maintain with them. An important finding of Study 2 is that the lower likeability and lesser preference for meaningful relationships of the woman who reacted with happiness were due in part to participants’ perception of this woman as being less competent and especially more superficial.

General Discussion

Results of both studies showed that both male and female participants reported liking the woman who reacted positively to the piropo less and also expressed a lower intention to establish interpersonal relations with her; they also viewed this woman as less competent and more superficial. The relation between the woman’s reaction to the piropo and her likeability was mediated by the superficiality and competence with which she was perceived.

Piropos are a very common form of sexual objectification and street harassment in Spain and other Spanish-speaking and Mediterranean countries. In the Spanish media and social networks, there is agreement on rejecting “lewd” piropos. However, opinions regarding “mild/gallant” piropos are divergent because they are accepted by some and rejected by others. The aim of the present research was to determine how women’s reactions after receiving “mild” piropos can affect how they are perceived. Based on the literature on person perception and attitudes toward gender roles, we explored how women are perceived based on whether they feel happy, angry, or indifferent when receiving a “mild/gallant” piropo. Our hypotheses were that women who reacted with happiness would be perceived according to traditional gender roles, that is, as less competent, less capable of leadership, more sociable, and more superficial. Consequently, women who reacted with happiness would be less liked and preferred for meaningful activities. Overall, the results supported our hypotheses, except in the case of capacity for leadership.

First, concerning the likeability of women and preference for sharing meaningful activities with them depending of their reactions to a “mild” piropo, some people argue that women should feel happy and empowered when receiving men’s attention to their bodies because that leads to a better assessment by others. Nevertheless, our results showed that male and female observers preferred the women who reacted with anger or with indifference (i.e., women who do not accept the traditional role related to women’s physical appearance). Thus, not only can women suffer negative consequences of not being valued or loved (i.e., backlash effects) when they behave in a masculine-stereotyped way (Rudman and Phelan 2008), but they also can be seen negatively when they behave in a feminine-stereotyped way by accepting the piropo, that is, reacting with happiness after being objectified by men because of their physical appearance. Our results are similar to those of Infanger et al. (2016) in that there are negative consequences for a woman who accepts the traditional role and is objectified by men--although the operationalization of this acceptance of the gender role is not the same in both studies--and that these effects are independent of the observer’s gender. However, the research by Infanger et al. (2016) supported the idea that the lower likeability of self-sexualized women in their research was due to the fact that women were perceived as powerful and challenging the gender hierarchy; by contrast, our results suggest a different explanation for the punishment of these women who conform to traditional roles. In our study, the lower likeability of women who feel happy when exposed to a piropo was due to them being perceived as more superficial and less competent. This pattern was quite consistent, and it was found not only in likeability judgments, but also in participants’ preferences for sharing meaningful relationships and activities with these women.

Second, perceiving the woman who reacted with happiness when exposed to a piropo as less competent supports traditional conceptions of women’s gender roles, according to which competence is not associated with women (Ellemers 2018; Fiske et al. 2002). The prescriptive aspect of female gender stereotypes (i.e., what women should be) indicates that women ought to be communal (i.e., kind, thoughtful, and sensitive to others’ feelings) (Rudman and Glick 2001) and not competent (Eagly and Mladinic 1989), at least not in masculine realms. Our results regarding competence are consistent with others that have shown that participants perceive women as being less competent after having just been exposed to a sexualized image of another woman (Rudman and Borgida 1995) or after focusing on the physical appearance of a woman versus focusing on her as a person (Heflick and Goldenberg 2009). Competence and warmth are two basic dimensions in social cognition, both for individuals and groups. The way in which we perceive others in these dimensions has important consequences for our relationships with them (Fiske et al. 2007; Wojciszke 2005). Specifically, to cite just a few examples, considering someone to be more or less competent influences how he or she is perceived in terms of leadership, in his or her assessment as a political candidate, in terms of interpersonal attraction, and whether he or she is hired and promoted within an organization (Cuddy et al. 2011). Our results support the idea that a woman who reacts with happiness when she is objectified and valued by her appearance--which is traditionally more associated to women than to men--is seen as less competent, a finding that we corroborated in two studies with different designs.

Regarding warmth, overall our results did not support our predictions. In Study 1, the three targets were evaluated similarly on this dimension. In Study 2, the woman who reacted with happiness was perceived as warmer only in comparison to the woman who reacted with indifference to a piropo. These results are in line with other studies that have shown that women are not always perceived as warm when they conform to traditional gender roles. For instance, Heflick et al. (2011) found in three studies that when perceivers focused on the target’s appearance (vs. on performance in Studies 1 and 3; vs. on the person in Study 2), they rated women (but not men) as less competent, warm, and moral. Moreover, competence and warmth were positively correlated in both Studies 1 and 2 by Heflick et al. (2011) suggesting that competence and warmth are not orthogonal, unrelated, or negatively related dimensions, but instead are positively related, perhaps reflecting the same positive evaluative meaning (Abele and Wojciszke 2014). In our study, the woman in the happiness condition may have been generally disliked for her reaction, which was reflected in the two measures of warmth and competence.

Perceptions of superficiality have scarcely been studied in previous research but our results show how important they are for likeability and interpersonal relationships. Superficiality is a negatively evaluated feature (as suggested by the results of a pilot study included in the Method section of Study 1), so it seems obvious that people will not like to have meaningful relationships with a superficial person. The finding concerning superficiality also supports our prediction that both men and women tend to dehumanize sexually objectified women (Heflick and Goldenberg 2009; Heflick et al. 2011; Vaes et al. 2011) in that profoundness could be considered as a uniquely human trait (Haslam and Loughnan 2014). The fact that the woman who reacted with happiness was clearly perceived as more superficial than the other two targets in both studies, with different measures of profoundness/superficiality, implies a negative view of this woman. It also suggests, as shown by the mediation analysis, that this view affected her likeability and selection for relevant relationships. Mediation analyses also indicated that superficiality was even more important than competence in terms of predicting likeability and preference for the targets.

In Study 2 we found that women perceived the targets (i.e., other women) as more competent, warmer, and less superficial than men, and women also liked the targets more and preferred them for both meaningful and less important activities and tasks. Specifically, the interaction between gender and target reaction to the piropo reflect a tendency of male participants to see the target who reacted with anger or indifference more negatively than female participants; women perceived these two targets as warmer and more likeable and preferred them for meaningful relationships more than men did. In regard to the target who reacted with happiness, female participants saw her as being more superficial, and both male and female participants did not show differences in terms of their assessments of her sociability, likeability, or selection for meaningful activities. These gender patterns can be explained in terms of women’s ingroup favoritism (Tajfel and Turner 1979), that is, a general tendency of women to evaluate other women more positively. Yet, it is also possible that men particularly reject women who do not accept traditional gender roles (i.e., those who react with indifference or anger) because they do not feel attracted to such women. For instance, the research of Vaes et al. (2011) showed a link between sexual attraction and objectification/dehumanization of women among men (but not among women).

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Some limitations of the current research open up new topics that could be explored in further research. One is related to the characteristics of the participants in both studies: college students. Research has shown that the opinion of the Spanish population is relatively negative towards gender stereotypes and sexism (Moya et al. 2000) and that this is especially true for college students (Moya et al. 2006). Yet, other studies with Spanish adolescents suggest that young men consider young women high in ambivalent sexism to be most attractive (Montañés et al. 2013). Therefore, studies with people from the general population might find less rejection of the woman who enjoyed the “mild” piropo, given that studies conducted in Spain (Moya et al. 2006) have shown that both age and educational level are negatively correlated with sexism.

A second limitation is related to the type of activities and relationships that we explored. We focused on some of them but there are obviously many more. Thus, future studies could analyze if the pattern of results we found is replicated in other types of relationships. We found a similar pattern of answers across male and female participants but the pattern may differ in other relationships and activities. The choice of testing only one example of piropos is also a limitation. A future line of research could examine whether the perceptions of women based on their reactions are the same with a “lewd” piropo, for example. Finally, many other mediators can be considered in the relation between a woman’s reaction to the piropo and her evaluation and likeability, such as woman’s perception in terms of humanity (Heflick and Goldenberg 2009) or as a threat (Infanger et al. 2016).

Practice Implications

Unlike other forms of harassment that are clearly rejected, piropos generate very diverse reactions among the Spanish population (Moya-Garófano et al. 2019). People who reject any type of piropos essentially consider that they reflect the objectification of women and the invasion of their privacy (Agudo 2015). However, others paint these perceptions as exaggerated and consider that receiving piropos is a natural practice that women should appreciate (Sust 2015). A more nuanced position is expressed by people who feel that certain obscenities that are shouted at women on the street should not be tolerated but that kind and pleasant comments need not be viewed as bad or prohibited (Ferreras 2015). This positive vision of some verbal comments from strangers does not seem limited to Spanish society. Recent legal measures trying to regulate stranger harassment in countries such as Portugal, Netherlands, and France suggest that directing comments to stranger women in a public space may still be a habitual and normalized practice within these societies. For instance, Ferreira Leite, a female Portuguese politician, points out that the recent law to combat stranger harassment in Portugal has its limits, for example, by “saying that someone is pretty doesn’t count” (Kearl 2016).

However, our results show that conforming with the traditional gender stereotype--in our study, a woman feeling happy because she is valued by her physical appearance-does not lead to a positive evaluation by social perceivers. Thus, raising awareness of the potential negative consequences of piropos with empirical data that counteract what some people defend based just in their opinions could be one of the first steps to fight for the eradication of this still extensive practice. Research may serve here as an important tool to reinforce a feminist message. Policymakers, media, activists, and educators should be concerned about combating not only the more direct and hostile forms of stranger harassment, but also the more subtle ones that may have a benevolent appearance but can still be damaging for women.

Conclusions

The main conclusion of our research is that conforming with the traditional gender stereotype--in our case a woman feeling happy because she is valued by her physical appearance--is not positively rewarded. Women, but also men, prefer to engage in important relationships with women who do not fit with the traditional gender role because both men and women prefer women who are competent and not superficial. Regarding those who argue that an elegant street piropo is something that does not hurt women and should therefore be welcomed (Ferreras 2015; Sust 2015), our results show that reacting with happiness to this kind of piropo has negative consequences for women. Our research does not show whether the woman who is happy when receiving a “mild/gallant” piropo feels empowered or increases her self-esteem, as the phenomenon known as “enjoyment of sexualization” suggests (Liss et al. 2011), but it does allow us to state that it does not increase her positive evaluation by social perceivers.

References

Abbey, A., Cozzarelli, C., McLaughlin, K., & Harnish, R. J. (1987). The effects of clothing and dyad sex composition on perceptions of sexual intent: Do women and men evaluate these cues differently? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 17, 108-126. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1987.tb00304.x.

Abele, A. E., & Wojciszke, B. (2014). Communal and agentic content in social cognition. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 50, 195-255. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-800284-1.00004-7.

Agudo, A. (2015, January 19). Carmona, no estás sola [Carmona, you are not alone]. [Web log post]. Retrieved from http://blogs.elpais.com/mujeres/2015/01/carmona-no-estás-sola.html.

Barreto, M., & Ellemers, N. (2005). The burden of benevolent sexism: How it contributes to the maintenance of gender inequalities. European Journal of Social Psychology, 33(5), 633-642. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.270.

Barreto, M., Ellemers, N., Piebinga, L., & Moya, M. (2010). How nice of us and how dumb of me: The effect of exposure to benevolent sexism on women’s task and relational self-descriptions. Sex Roles, 62, 532-544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9699-0.

Becker, J. C., Glick, P., Ilic, M., & Bohner, G. (2011). Damned if she does, damned if she doesn’t: Consequences of accepting versus confronting patronizing help for the female target and male actor. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 761-773. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.823.

Becker, J. C., Zawadzki, M. J., & Shields, S. A. (2014). Confronting and reducing sexism: A call for research on intervention. Journal of Social Issues, 70, 603-614. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12081.

Bowman, C. G. (1993). Street harassment and the informal ghettoization of women. Harvard Law Review, 106, 517-580 https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/facpub/142.

Buss, D. M., Abbott, M., Angleitner, A., Asherian, A., Biaggio, A., Blanco-Villasenor, A., … Yang, K. S. (1990). International preferences in selecting mates: A study of 37 cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 21, 5-47. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022190211001.

Buss, D. M., Shackelford, T. K., Kirkpatrick, L. A., & Larsen, R. J. (2001). A half century of mate preferences: The cultural evolution of values. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63(2), 491-503. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00491.x.

Cahoon, D. D., & Edmonds, E. M. (1989). Male-female estimates of opposite-sex first impressions concerning females’ clothing styles. Bulletin of the Psychonomic Society, 27, 280-281. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03334607.

Chan, K. Y., & Drasgow, F. (2001). Toward a theory of individual differences and leadership: Understanding the motivation to lead. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86, 481-498.

Cikara, M., Eberhardt, J. L., & Fiske, S. T. (2011). From agents to objects: Sexist attitudes and neural responses to sexualized targets. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23(3), 540-551. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2010.21497.

Crocker, J., Karpinski, A., Quinn, D. M., & Chase, S. K. (2003). When grades determine self-worth: Consequences of contingent self-worth for male and female engineering and psychology majors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 507-516. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.3.507.

Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Beninger, A. (2011). The dynamics of warmth and competence judgments, and their outcomes in organization. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 73-98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2011.10.004.

Czopp, A. M., & Monteith, M. J. (2003). Confronting prejudice (literally): Reactions to confrontations of racial and gender bias. Bulletin Personality and Social Psychology, 29, 532-544. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167202250923.

Dodd, E. H., Giuliano, T., Boutell, J., & Moran, B. E. (2001). Respected or rejected: Perceptions of women who confront sexist remarks. Sex Roles, 45, 567-577. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1014866915741.

Eagly, A. H., & Karau, S. J. (2002). Role congruity theory of prejudice toward female leaders. Psychological Review, 109, 573-598. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-295X.109.3.573.

Eagly, A. H., & Mladinic, A. (1989). Gender stereotypes and attitudes toward women and men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15, 543-558. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167289154008.

Ellemers, N. (2018). Gender stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(1), 275-298. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719.

Fairchild, K., & Rudman, L. (2008). Everyday stranger harassment and women’s objectification. Social Justice Research, 21, 338-357. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-008-0073-0.

Ferreras, C. (2015, January 15). Quieren prohibir el piropo [they want to forbid the piropo]. La Opinión de Zamora. Retrieved from http://www.laopiniondezamora.es/opinion/2015/01/15/quieren-prohibir-piropo/815536.html.

Fiske, S. T., & Taylor, S. E. (2017). Social cognition: From brains to culture (3rd ed.). London: Sage.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 878-902. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.82.6.878.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social perception: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Science, 11, 77-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005.

Forbes, G. B., Doroszewicz, K., Card, K., & Adams-Curtis, L. (2004). Association of the thin body ideal, ambivalent sexism, and self-esteem with body acceptance and the preferred body size of college women in Poland and the United States. Sex Roles, 50, 331-345. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:sers.0000018889.14714.20.

Forbes, G. B., Collinsworth, L. L., Jobe, R. L., Braun, K. D., & Wise, L. M. (2007). Sexism, hostility toward women, and endorsement of beauty ideals and practices: Are beauty ideals associated with oppressive beliefs? Sex Roles, 56, 265-273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9161-5.

Franzoi, S. L. (2001). Is female body esteem shaped by benevolent sexism? Sex Roles, 44, 177-188. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:101090300.

Fredrickson, B., & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173-206. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Fridlizius, N. (2009). Me gustaría ser baldosa…Un estudio cualitativo sobre el uso actual de los piropos callejeros en España [I would like to be a paving stone… A qualitative study about the current use of street piropos in Spain] (doctoral dissertation). Göteborgs Universitet. Retrieved from https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/21649?mode=full.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). Ambivalent sexism. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 33, pp. 115-188). Thousand Oaks, CA: Academic Press.

Glick, P., Larsen, S., Johnson, C., & Branstiter, H. (2005). Evaluations of sexy women in low- and high-status jobs. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 29, 389-395. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00238.x.

Haines, E. L., Deaux, K., & Lofaro, N. (2016). The times they are a-changing … or are they not? A comparison of gender stereotypes, 1983-2014. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 40(3), 353-363. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684316634081.

Haslam, N., & Loughnan, S. (2014). Dehumanization and infrahumanization. Annual Review of Psychology, 65, 399-423. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115045.

Heflick, N., & Goldenberg, J. (2009). Objectifying Sarah Palin: Evidence that objectification causes women to be perceived as less competent and less fully human. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 598-601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.008.

Heflick, N., Goldenberg, J., Cooper, D., & Puvia, E. (2011). From women to objects: Appearance focus, target gender, and perceptions of warmth, morality and competence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 572-581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2010.12.020.

Infanger, M., Rudman, L. A., & Sczesny, S. (2016). Sex as a source of power? Backlash against self-sexualizing women. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19(1), 110-124. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430214558312.

International Society of Aesthetics Plastic Surgery. (2017). 2017 ISAPS Global Survey. Retrieved from https://www.isaps.org/medical-professionals/isaps-global-statistics.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2015). Features of objectified body consciousness and sociocultural perspectives as risk factors for disordered eating among late-adolescent women and men. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(4), 741-752. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000096.

Jones, D. C., & Crawford, J. K. (2006). The peer appearance culture during adolescence: Gender and body mass variations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 2, 257-269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-9006-5.

Judd, C. M., Kenny, D. A., & McClelland, G. H. (2001). Estimating and testing mediation and moderation in within-subject designs. Psychological Methods, 6(2), 115-134. https://doi.org/10.1037//1082-989X.6.2.115.

Kearl, H. (2016, February 19). Portugal’s law against street harassment [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.stopstreetharassment.org/2016/02/portugallaw/.

La presidenta del Observatorio contra la Violencia de Género pide que se erradique el piropo [The president of the Spanish Observatory of Violence Against Women asks for the eradication of piropo]. (2015, January 9). El Periódico. Retrieved from http://www.elperiodico.com/es/noticias/sociedad/observatorio-contra-violencia-genero-pide-vetar-piropo-3838083

Lee, T. L., Fiske, S. T., Glick, P., & Chen, Z. (2010). Ambivalent sexism in close relationships: (hostile) power and (benevolent) romance shape relationship ideals. Sex Roles, 62, 583-601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9770-x.

Liss, M., Erchull, M. J., & Ramsey, L. R. (2011). Empowering or oppressing? Development and exploration of the enjoyment of Sexualization scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(1), 55-68. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167210386119.

Loughnan, S., Haslam, N., Murnane, T., Vaes, J., Reynolds, C., & Suitner, C. (2010). Objectification leads to depersonalization: The denial of mind and moral concern to objectified others. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40, 709-717. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.75510.1002/ejsp.755.

Mahalik, J. R., Morray, E. B., Coonerty-Femiano, A., Ludlow, L. H., Slattery, S. M., & Smiler, A. (2005). Development of the conformity to feminine norms inventory. Sex Roles, 52(7/8), 417-435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-3709-7.

Manago, A. M., Ward, M. L., Lemm, K. M., Reed, L., & Seabrook, R. (2015). Facebook involvement, objectified body consciousness, body shame, and sexual assertiveness in college women and men. Sex Roles, 72, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0441-1.

Matthews, J. L. (2007). Hidden sexism: Facial prominence and its connections to gender and occupational status in popular print media. Sex Roles, 57(7-8), 515-525.

Montañés, P., de Lemus, S., Moya, M., Bohner, G., & Megías, J. L. (2013). How attractive are sexist intimates to adolescents? The influence of sexist beliefs and relationship experience. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(4), 494-506. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313475998.

Montoya, A. K., & Hayes, A. F. (2017). Two condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: A path-analytic framework. Psychological Methods, 22, 6-27. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000086.

Moya, M., Expósito, F., & Ruiz, J. (2000). Close relationships, gender, and career salience. Sex Roles, 42(9/10), 825-846. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1007094232453.

Moya, M., Expósito, F., & Padilla, J. L. (2006). Revisión de las propiedades psicométricas de las versiones larga y reducida de la Escala sobre Ideología de Género [review of the psychometrics properties of the long and short gender ideology scale]. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 6, 709-727.

Moya, M., Glick, P., Expósito, F., de Lemus, S., & Hart, J. (2007). It’s for your own good: Benevolent sexism and women’s reactions to protectively justified restrictions. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(10), 1421-1434. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207304790.

Moya-Garófano, A., & Moya, M. (2019). Focusing on one’s own appearance leads to body shame in women but not men: The mediating role of body surveillance and appearance-contingent self-worth. Body Image, 29, 58-64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.02.008.

Moya-Garófano, A., Rodríguez-Bailón, R., Moya, M., & Megías, J. L. (2018). Stranger harassment (“piropo”) and women's self-objectification: The role of anger, happiness and empowerment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518760258.

Moya-Garófano, A., Megías, J. L., Moya, M. & Rodríguez-Bailón, R. (2019). Ambivalent sexism and women’s reactions to stranger harassment: The case of piropos in Spain. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Nowatzki, J., & Morry, M. M. (2009). Women’s intentions regarding, and acceptance of, self-sexualizing behavior. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 95-107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01477.x.

Park, L. E., Diraddo, A. M., & Calogero, R. M. (2009). Sociocultural influence and appearance-based rejection sensitivity among college students. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 108-119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01478.x.

Profound (n.d.). In http://www.OxfordDictionaries.com. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/profound.

Real Academia Española. (2019a). Piropo [Piropo]. In Diccionario de la lengua española [Dictionary of the Spanish language] (23rd ed.). Madrid, Spain: Author. Retrieved from http://buscon.rae.es/srv/search?id=Qnd2pX8okE2x5wMBqzWG.