Opinion Statement

Benefits of liver transplantation (LT) for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) are well established. However, there is debate regarding optimal and equitable selection of patients best served by LT, particularly in the face of limited organ availability. Herein, we discuss topics regarding LT selection criteria for patients with HCC. Recent change in UNOS policy currently mandates a 6-month observation period prior to priority listing and institutes a cap of 34 MELD exception points for patients with HCC. Additionally, two further proposed changes to UNOS policy include (1) requiring locoregional therapy for those with small (2–3 cm) unifocal HCC prior to applying for exception points and (2) allowing downstaging in select patients with UNOS T3 lesions. These policies move beyond simply using tumor burden to using markers of tumor biology for selecting patients who have the lowest risk of post-transplant recurrence and best chance at long-term post-transplant survival. Given increasing time on transplant waiting lists and shortage of donor grafts, LT should be reserved for patients who may achieve significant benefit compared to non-transplant therapies. Potential benefit to HCC patients must be weighed against the harm from delaying or precluding LT for non-HCC patients on the waiting list, particularly in regions with limited donor availability. The relative benefit of LT in patients with small (<3 cm) HCC is likely limited; surgical resection (in absence of portal hypertension) and local ablative therapy (if portal hypertension present) are both efficacious and more cost-effective and should likely be regarded as first line therapies for these patients. Salvage LT can be considered as a rescue option for those with recurrent disease. Downstaging for selected patients with UNOS T3 lesions may identify those with good tumor biology and acceptable post-transplant outcomes; however, current studies have had a wide variation in reported outcomes. While awaiting more data, a standardized downstaging protocol including a priori inclusion criteria and a mandatory waiting time prior to LT to observe tumor biology likely yields the best outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the third leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide and a leading cause of death in patients with cirrhosis [1]. Despite advances in available therapies for HCC, median survival remains less than 1 year. Prognosis is largely determined by tumor stage, with curative options only available for patients with early stage tumors. Liver transplantation (LT) is an ideal treatment for selected patients with HCC, as it removes both the tumor and the underlying cirrhotic liver, with 5-year survival rates exceeding 70% [2]. Although the benefits of LT for patients with HCC are clear, there is ongoing debate regarding the selection of patients best served by LT, particularly in the face of limited organ availability. Proposals to amend current organ allocation policy aim to address the equitable allocation of organs for both HCC and non-HCC patients. These discussions are particularly significant and timely, as HCC patients comprise a growing proportion of the LT waitlist. In this review, we will discuss several topics regarding LT criteria for patients with HCC.

Delayed MELD exceptions points

The Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, a predictor of 3-month mortality in patients with cirrhosis, is used to prioritize patients for LT; however, it underestimates the risk of mortality in patients with HCC. Accordingly, patients with HCC within Milan criteria (single lesion ≤5 cm or up to 3 lesions ≤3 cm) were provided with additional MELD exception points starting in 2002 to balance their risk of tumor progression while awaiting LT compared to the 3-month liver-related mortality risk of non-HCC patients. Subsequent data suggested HCC patients were at a disproportionate advantage to receive LT compared to non-HCC patients, with additional MELD points often overestimating the likelihood of tumor progression and subsequent mortality. Thus, the MELD exception policy has since been adjusted several times (Table 1).

Revisions to UNOS policy in 2003 and 2005 focused on the number of exception points awarded to HCC patients, while the most recent change in 2015 instead addressed the timing of exception points. Previously, HCC patients were awarded priority listing with a MELD exception score of 22, which was subsequently increased every 3 months until either receipt of LT or drop-off from the waitlist. Under the recently adopted policy, patients are initially listed with their natural MELD score and are later awarded a MELD exception score of 28 points after a 6-month waiting period; exception points then increase every 3 months to a maximum score or “cap” of 34 points. Heimbach and colleagues explored the optimal timing of exception points in a modeling study using Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) data. They compared rates of transplant between HCC and non-HCC candidates using the following scenarios: allocation of an immediate MELD exception score of 22, 3-month delay before granting 25 exception points, 6-month delay before granting 28 exception points, and 9-month delay before granting 29 exception points. The strategies yielded transplant rates of 108.7, 65.0, 44.2, and 33.6 per 100 person-years, respectively, for HCC patients, compared to 30.1, 32.5, 33.9, and 34.8 transplants per 100-person years for non-HCC candidates [3••]. The authors concluded a 6–9-month delay in receipt of exception points reduces disparity in transplant rates between HCC and non-HCC candidates.

A mandatory 6-month waiting period prior to application of MELD exception points facilitates selection of patients with good tumor biology and lower risk of post-transplant recurrence. Tumor burden, which is assessed by radiologic parameters and used for patient selection, is an imperfect surrogate for tumor biology, as there is variation in natural history and treatment responsiveness between patients. Although patients within Milan criteria typically have high recurrence-free survival rates, post-LT recurrence is still observed in ~10% of patients [4]. Many potential markers of tumor biology are unfortunately not available pre-transplant (e.g., presence of microvascular invasion), not validated, or insufficiently accurate. Although shorter wait times may reduce the risk of waitlist drop-out and pre-transplant mortality as a result of tumor progression, this does not allow for adequate time to assess tumor biology. An analysis of the UNOS database found HCC patients receiving LT in regions with shorter wait times have significantly higher risk of post-transplant mortality than those transplanted in long waiting time regions (HR 1.55, 95% CI 1.38–1.74) [5]. Similarly, a multi-center study with 881 HCC patients found waiting time less than 6 months is predictive of post-transplant recurrence (HR 3.0, 95% CI 1.2–7.0) [6•]. While patients with aggressive tumor biology can go unrecognized with short wait times, they would likely drop-off the waiting list due to tumor progression with observation over longer wait times.

Patients with UNOS T1 HCC

Patients with unifocal T1 lesions, i.e., smaller than 2 cm, are ineligible for MELD exception points given the potential for misdiagnosis, perceived low risk of drop-out, and availability of effective alternate therapies. There is practice variation in management of these lesions; some centers opt for close observation until the lesion reaches 2 cm, while others proceed with locoregional therapy before the patient qualifies for MELD exception points. While ablation of T1 lesions is associated with 5-year tumor-free survival rates of 38–60% and is cost effective in patients with compensated cirrhosis [7,8,9], the optimal strategy is less clear for those with decompensated cirrhosis who might otherwise benefit from LT. In a study evaluating the “Wait and not Ablate” strategy among 114 patients with 1–1.9 cm HCC, median tumor growth was only 0.14 cm/month; however, the probabilities of progressing from T1 to directly beyond T2 without transplant listing at 6 and 12 months were 4.4 and 9.0%, respectively [10•]. Although elevated AFP was a risk factor for tumor progression and waitlist drop-out, there are no predictive models available to accurately identify those at highest risk.

Patients with small (2–3 cm) UNOS T2 HCC

Multiple effective treatment options exist for patients with small, unifocal HCC, including surgical resection, local ablative therapies, and LT [11]. Although LT offers cure of the underlying cirrhosis in addition to lower HCC recurrence rates compared to resection or local ablative therapy, post-transplant patients require long-term immunosuppression, which also carries associated risks and costs. Further, limited organ availability can create prolonged waiting times, allowing potential for tumor progression and increasing waiting list drop-out for both HCC patients and non-HCC patients.

Due to logistical and ethical obstacles, randomized controlled trials comparing these therapies have not been conducted. Thus, current decisions are primarily informed by observational and modeling studies. A systematic review of observational studies demonstrated similar 1-year survival for LT compared to resection (OR 1.08, 95%CI 0.81–1.43), but improved 3- and 5-year survival rates for LT (OR 1.47, 95% CI 1.18–1.84 and OR 1.77, 95% CI 1.45–2.16, respectively) [12]. It is important to note these data have limitations including confounding given use of strict medical and social selection criteria for LT but not resection. Vitale and colleagues evaluated “transplant benefit”, defined as the difference in survival with and without LT, by comparing observed survival after resection to expected post-transplant survival among 1106 HCC patients with compensated cirrhosis [13•]. MELD score and microvascular invasion were the strongest predictors of transplant benefit, with transplant having a survival benefit only in patients with MELD ≥10 and without microvascular invasion. The 5-year survival rates were 67% in patients with MELD <10 vs. 47% in those with MELD ≥10.

Surgical resection is reserved for those with Child Pugh A cirrhosis and without portal hypertension, however, local ablative therapies can be used for patients with portal hypertension. Prior studies have demonstrated local ablative therapies to be highly effective with complete response rates exceeding 90% for small tumors less than 3 cm in maximum diameter [14]. Although 50–70% of patients have HCC recurrence within 5 years of local ablative therapy, some patients achieve a long-term complete response obviating the need for LT.

Currently, some patients with small unifocal HCC who are candidates for locoregional therapies and may otherwise do well without LT still undergo transplantation. Thus, the MELD Exceptions and Enhancements Subcommittee is considering a change to the current MELD exception policy for patients with small (2–3 cm) unifocal lesions, requiring use of locoregional therapy prior to the allocation of MELD exception points. Patients with compensated cirrhosis and complete response to locoregional therapy would not be awarded exception points, while those with residual HCC would be prioritized. Patients with tumor recurrence after locoregional therapy could be awarded exception points without having to complete the 6-month waiting period. In patients for whom locoregional therapy is not possible, transplant centers may ask the regional review board for an exception to this policy.

Patients with UNOS T3 HCC

While patients with HCC exceeding Milan criteria are typically ineligible for priority listing, some question whether the Milan criteria are too restrictive and preclude LT in a subset of patients who might benefit from transplant. Therefore, several potential expanded selection criteria have been proposed with acceptable post-transplant outcomes [15,16,17] (Table 2). Notably, most studies comparing outcomes between expanded criteria and Milan criteria used pathologic data (which is may not be available pre-transplant without biopsy) rather than radiographic data, which only has 44% concordance [18]. Further, several studies reported data as a single cohort, in which data from expanded criteria patients were mixed with patients within Milan criteria, which may result in underestimation of recurrence risk and overestimation of post-transplant survival. Finally, most studies had small sample sizes, which inherently limit statistical power.

In a single-center study from UCLA, patients within UCSF criteria (n = 185) had numerically lower survival than patients within Milan criteria (n = 173), with 5-year recurrence-free survival rates of 65 vs. 74%, although this did not reach statistical significance (p = 0.09) [19]. Similarly, a retrospective analysis among 6012 HCC patients from the China Liver Transplant Registry found patients exceeding Milan but fulfilling UCSF or Hangzhou criteria had lower recurrence-free post-transplant survival, though again, the difference did not reach statistical significance [20]. However, data from the Simmons Transplant Institute suggest patients meeting Region 4 criteria (n = 49) had significantly worse outcomes compared to those meeting Milan criteria (n = 176) [21]. Patients meeting Region 4 criteria were significantly more likely to have microvascular invasion on explant (22 vs. 5%, p = 0.002), higher AFP levels (median 21.9 vs.8.5, p = 0.01), higher recurrence rates (13 vs. 5%, p = 0.05), and worse survival (5-year survival 69 vs. 79%, p = 0.03). A meta-analysis including 19 studies found patients exceeding Milan criteria had higher post-transplant mortality (HR 1.68, 95% CI 1.39–2.03) than those meeting Milan criteria [2].

In order to more directly assess tumor biology prior to LT, the Toronto criteria have been proposed as a way to select which patients may be transplantable beyond Milan criteria. The authors propose use of histology (i.e., poorly differentiated tumors on biopsy), presence of HCC-related symptoms (weight loss, decline in functional status), and markedly elevated AFP (AFP > 500 ng/mL) in deciding which patients should be excluded from LT consideration. In a prospective analysis comparing post-LT outcomes of patients who met traditional Milan criteria (n = 138) to those who were beyond Milan but met Toronto criteria (n = 105), the patients beyond Milan had higher post-LT recurrence (29.8%) but still had 10-year survival exceeding 40%, which is higher than expected for patients with T3 HCC [22]. The excellent post-LT survival was in part secondary to aggressive post-LT HCC surveillance and management of recurrent HCC. While this criterion requires further validation, it is the most direct measure of tumor biology prior to LT that has been proposed to date.

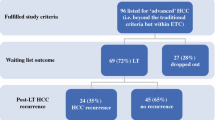

Downstaging, i.e., use of locoregional therapies to bring UNOS T3 tumors within Milan criteria has multiple benefits. It not only allows for reduction in tumor burden, potentially facilitating LT, but also provides an observation period to assess tumor biology. In a single center study among 114 patients, Yao and colleagues used a prospective downstaging protocol, with a priori inclusion criteria and a mandatory 3-month waiting period prior to LT [23]. After a median 9.8-month time from downstaging to LT, downstaging was successful in 65.3% and post-transplant recurrence rates were 7.5%, which was comparable to those who initially presented within Milan criteria. When a similar downstaging protocol was expanded to several Region 5 centers, similar results were observed, with 13% 5-year recurrence rates [24]. While these results are favorable, they are not universal, as shown in a systematic review of the literature [25•]. While more data is needed, it appears a priori inclusion criteria, a mandatory waiting time prior to LT to observe tumor biology, and a standardized downstaging protocol is an approach that may yield the best outcomes and minimize post-transplant recurrence.

Though selected patients with HCC exceeding Milan criteria may benefit from LT, this benefit must be weighed against the potential harm from delaying or preventing transplantation for other non-HCC patients on the waiting list, particularly in regions with limited donor availability. The harms of expanding selection criteria typically outweigh the benefits when 5-year post-transplant survival rates fall below 61% [26]. As expected, the risk-benefit ratio varies significantly between regions, with less harm to non-HCC patients in regions with higher organ availability.

The MELD exceptions and Enhancements Subcommittee are considering a change to the MELD exception policy in which patients with tumor burden exceeding Milan criteria would be eligible for inclusion in a downstaging protocol. This includes patients with 1 lesion >5 cm and ≤8 cm, those with 2–3 lesions each <5 cm and total diameter ≤ 8 cm, and those with 4–5 lesions each <3 cm with total diameter ≤ 8 cm. Patients must complete locoregional therapy and subsequently meet requirements for T2 HCC. Similar to the mandatory 6-month waiting period, this policy change aims to select patients with good tumor biology and lower risk of post-transplant recurrence.

Summary

LT plays an important role in the management of patients with HCC, providing the best opportunity for long-term recurrence-free survival. However, given increasing time on transplant waiting lists and a shortage of donor grafts, LT should be reserved for patients who achieve significant benefit compared to non-transplant therapies. We have proposed an algorithm with recommended treatments for patients with HCC in Fig. 1.

There have been recent changes in UNOS policy to aid in the selection of patients who derive most benefit from LT. The most recently implemented change in UNOS policy mandates a 6-month observation period prior to priority listing and instituted a cap of 34 MELD exception points. Two proposed changes to the MELD exception policy currently under consideration include requiring locoregional therapy for those with small (2–3 cm) unifocal HCC prior to applying for exception points and allowing downstaging for select patients with lesions exceeding Milan criteria. These policies signify a change in philosophy of moving beyond tumor burden, which is insufficiently predictive of post-transplant outcomes, to assessing markers of tumor biology to select those who have the lowest risk of post-transplant recurrence and best chance of long-term post-transplant survival. Doing so should maximize LT benefit in HCC patients while promoting the more equitable allocation of a limited supply of donor organs between HCC and non-HCC patients on the waiting list.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1118–27.

Mazzaferro V, Bhoori S, Sposito C, et al. Milan criteria in liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: an evidence-based analysis of 15 years of experience. Liver Transpl. 2011;17(Suppl 2):S44–57.

•• Heimbach JK, Hirose R, Stock PG, et al. Delayed hepatocellular carcinoma model for end-stage liver disease exception score improves disparity in access to liver transplant in the United States. Hepatology. 2015;61(5):1643–50. Authors demonstrated a 6–9-month delay in receipt of MELD exception points reduces disparity in transplant rates between HCC and non-HCC candidates.

Sotiropoulos GC, Molmenti EP, Losch C, et al. Meta-analysis of tumor recurrence after liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma based on 1,198 cases. Eur J Med Res. 2007;12(10):527–34.

Halazun KJ, Patzer RE, Rana AA, et al. Standing the test of time: outcomes of a decade of prioritizing patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, results of the UNOS natural geographic experiment. Hepatology. 2014;60(6):1957–62.

• Mehta N, Heimbach J, Harnois DM, et al. Short waiting time predicts early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after liver transplantation: a multicenter study supporting the “ablate and wait” principle. Paper presented at: The Liver Meeting 2014; Boston, MA. Multi-center study demonstrated liver transplant waiting times less than 6 months is predictive of post-transplant recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Wang JH, Wang CC, Hung CH, et al. Survival comparison between surgical resection and radiofrequency ablation for patients in BCLC very early/early stage hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56(2):412–8.

Hung HH, Chiou YY, Hsia CY, et al. Survival rates are comparable after radiofrequency ablation or surgery in patients with small hepatocellular carcinomas. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(1):79–86.

Naugler WE, Sonnenberg A. Survival and cost-effectiveness analysis of competing strategies in the management of small hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl. 2010;16(10):1186–94.

• Mehta N, Sarkar M, Dodge JL, Fidelman N, Roberts JP, Yao FY. Intention-to-treat outcome of T1 hepatocellular carcinoma with the “wait and not ablate” approach until meeting T2 criteria for liver transplant listing. Liver Transpl. 2016;22(2):178–87. The risk of tumor progression from T1 directly to beyond T2 is low (< 5%) within 6 months, although the ideal strategy in these patients (immediate ablation vs. watchful waiting) remains unknown.

Nathan H, Segev DL, Mayo SC, et al. National trends in surgical procedures for hepatocellular carcinoma: 1998-2008. Cancer. 2012;118(7):1838–44.

Zheng Z, Liang W, Milgrom DP, et al. Liver transplantation versus liver resection in the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Transplantation. 2014;97(2):227–34.

• Vitale A, Huo TL, Cucchetti A, et al. Survival benefit of liver transplantation versus resection for hepatocellular carcinoma: impact of MELD score. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22(6):1901–7. Surgical resection is the cost effective approach to HCC patients with compensated cirrhosis if MELD score is below 10 and there is no evidence of microvascular invasion.

Cho YK, Kim JK, Kim MY, et al. Systematic review of randomized trials for hepatocellular carcinoma treated with percutaneous ablation therapies. Hepatology (Baltimore, Md). 2009;49(2):453–9.

Zheng SS, Xu X, Wu J, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: Hangzhou experiences. Transplantation. 2008;85(12):1726–32.

Guiteau JJ, Cotton RT, Washburn WK, et al. An early regional experience with expansion of Milan criteria for liver transplant recipients. Am J Transplant Off J Am Soc Transplant Am Soc Transplant Surg. 2010;10(9):2092–8.

Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. 2001;33(6):1394–403.

Freeman RB, Mithoefer A, Ruthazer R, et al. Optimizing staging for hepatocellular carcinoma before liver transplantation: a retrospective analysis of the UNOS/OPTN database. Liver Transpl. 2006;12(10):1504–11.

Duffy JP, Vardanian A, Benjamin E, et al. Liver transplantation criteria for hepatocellular carcinoma should be expanded: a 22-year experience with 467 patients at UCLA. Ann Surg. 2007;246(3):502–9. discussion 509-511

Xu X, Lu D, Ling Q, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria. Gut. 2016;65(6):1035–41.

Kim PT, Onaca N, Chinnakotla S, et al. Tumor biology and pre-transplant locoregional treatments determine outcomes in patients with T3 hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing liver transplantation. Clin Transpl. 2013;27(2):311–8.

Sapisochin G, Goldaracena N, Laurence JM, et al. The extended Toronto criteria for liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective validation study. Hepatology. 2016;64(6):2077–88.

Yao FY, Mehta N, Flemming J, et al. Downstaging of hepatocellular cancer before liver transplant: long-term outcome compared to tumors within Milan criteria. Hepatology. 2015;61(6):1968–77.

Mehta N, Guy J, Frenette CT, et al. Multicenter Study of Down-staging of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) to within Milan criteria before liver transplantation (LT). Paper presented at: The Liver Meeting Boston, MA; 2014

• Parikh ND, Waljee AK, Singal AG. Downstaging hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Liver Transpl. 2015;21(9):1142–52. There is variation in post-transplant recurrence rates and post-transplant survival with downstaging, although a priori inclusion criteria, mandatory waiting time prior to transplantation, and a standardized downstaging protocol are the approaches that likely yield the best outcomes.

Volk ML, Vijan S, Marrero JA. A novel model measuring the harm of transplanting hepatocellular carcinoma exceeding Milan criteria. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(4):839–46.

Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):35–43.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Nicole Rich and Neehar D. Parikh declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Amit G. Singal reports personal fees from Bayer, Eisai, EMD Serano, and Wako Diagnostics but none are directly relevant to this manuscript.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Liver

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rich, N.E., Parikh, N.D. & Singal, A.G. Hepatocellular Carcinoma and Liver Transplantation: Changing Patterns and Practices. Curr Treat Options Gastro 15, 296–304 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-017-0133-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11938-017-0133-3