Abstract

A variety of biological, psychological, and social factors interact to influence pain. This article focuses on two distinct, but connected, psychological factors—positive personality traits and pain catastrophizing—and their link with pain perception in healthy and clinical populations. First, we review the protective link between positive personality traits, such as optimism, hope, and self-efficacy, and pain perception. Second, we provide evidence of the well-established relationship between pain catastrophizing and pain perception and other related outcomes. Third, we outline the inverse relationship between positive traits and pain catastrophizing, and offer a model that explains the inverse link between positive traits and pain perception through lower pain catastrophizing. Finally, we discuss clinical practice recommendations based on the aforementioned relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Pain is a complex phenomenon influenced by a variety of biological, psychological, and social factors [1]. Psychological factors are powerful predictors of the experience of pain [2] and psychological models focus on the characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that influence pain perception. Personality is one such characteristic. Together, personality traits and other patterns of thoughts and feelings, such as depression and anxiety, are modeled as either protective or as risk factors for pain. The disease model has focused traditionally on psychological deficits that pose risk factors for pain and related outcomes, such as quality of life or functional impairment [3]. However, more holistic models have been developed to include a focus on protective psychological factors or attributes that promote health, lower pain perception, and increase quality of life [4, 5].

Considering psychological health, it is noted that health is not just the absence of stress or mental illness (i.e., languishing), but also the presence of flourishing (i.e., well-being) [6]. Flourishing entails three factors that reflect psychological health: positive emotions, which indicate emotional well-being, such as positive affect and quality of life; positive psychological functioning, which reflects psychological well-being, such as self-acceptance and personal growth; and positive social functioning, which indicates social well-being, such as social contribution and social integration. The presence of positive personality traits, such as optimism, is indicative of flourishing. This article examines the protective link provided by positive personality traits, including optimism, hope, and self-efficacy, and how these traits may influence pain perception. Further, we will discuss extensive research that has defined the well-established relationship between the potential risk factor, pain catastrophizing, a maladaptive coping mechanism, and pain perception and other related outcomes. Additionally, we will review the inverse relationship between positive traits and pain catastrophizing, and offer a model that explains the inverse link between positive traits and pain perception through lower pain catastrophizing. Finally, we discuss clinical practice recommendations based on the aforementioned relationships.

Methods

We reviewed primary source research articles that were published or in press from January 2000 to January 2013. We retrieved studies between September 2012 and January 2013 from the online databases PubMed, Psych Info, Google Scholar and Academic Premier using the following keywords alone and in combination: pain catastrophizing, pain perception, pain, positive traits, optimism, hope, self-efficacy, and depression.

Positive Traits and Pain Perception

Numerous studies have demonstrated a protective link between positive personality traits and pain perception [7]. A majority of studies have focused on optimism in clinical populations and shown how optimism may predict or indicate the strength of the relationship between pain and many important life outcomes. Optimism is a generalized expectancy for positive outcomes [8] and is often measured with the Life Orientation Test-Revised (see Table 1). Clinical populations studied include patients with cancer [9, 10], sickle cell disease [11], osteoarthritis [12], and face pain [13]. Among 218 late-stage cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, optimism played a small protective role with severity of pain [9]. Among 334 lung cancer patients, optimism partially mediated the link between pain and quality of life [10]. A similar finding emerged with 72 older adults with osteoarthritis in that optimism partially explained the relationship between pain and life satisfaction [12]. In a study of 27 adolescents with sickle cell disease, optimism moderated the relationship between use of pain medication and pain severity [11]. Specifically, an adaptive pattern of opioid use was present among those with medium and high, but not low, optimism.

Additionally, optimism has been linked with pain response among patients with temporomandibular disorder (TMD) [14]. In a case control study of 20 patients (TMD) and 28 pain-free controls, TMD patients with lower optimism had lower pain tolerance times and higher pain unpleasantness in an ischemic pain task following a stressor compared with controls and TMD patients with higher optimism. Furthermore, TMD patients with lower optimism had higher biomarkers of stress response [norepinephrine and interleukin-6 (IL-6)] during experimental stress compared with TMD patients with higher optimism. Interestingly, lower optimism was associated with higher IL-6 at baseline, indicating a possible susceptibility towards greater inflammatory stress response. A large (n = 5,696) cross-sectional study of TMD patients also found an inverse relationship between optimism and facial pain [13]. Importantly, the association was only present among patients without depression. In addition, studies have demonstrated that optimism is protective against pain when recovering from surgery, including inguinal hernia repair [15], arthroscopic knee surgery [16], and coronary artery bypass graft surgery [17].

Research with non-clinical samples has helped elucidate mechanisms by which optimism may protect against pain. Those higher in optimism were more responsive to a placebo expectation for analgesia, experiencing less pain in response to a cold pressor task than those in a no-expectation condition [18, 19]. It is speculated that those higher in optimism are more inclined to respond to positive placebo expectations [18]. Further, the placebo response characteristic of optimists is likely aided by lower state anxiety at subsequent painful events [19]. The consistent negative association between optimism and pain in many studies has led to concern that optimistic individuals may disengage from confronting health issues [20]. However, it has been demonstrated the healthy participants with higher optimism exhibit the expected pain response (less pain and cardiovascular reactivity) under typical circumstances, but that this pattern is eliminated when primed to think about health and wellness. The results of this study provide evidence that optimists do not “blindly” accept pain that warrants action, but that they shift into an approach-oriented coping mode. Finally, a healthy sample of 149 diverse participants demonstrated that the protective link between optimism and pain perception holds across ethnic groups [21].

Although the link between optimism and pain has received a majority of attention in the literature, some research exists on the link between hope and pain. Whereas optimism is a generalized expectancy for positive outcomes [8], hope taps goal-directed thinking and consists of pathways (perceived routes toward goals) and agency (motivation to pursue routes toward goals), as conceptualized by Snyder [22]. Among healthy participants, higher dispositional hope has been linked with higher pain threshold, longer pain tolerance, and lower pain perception in a cold pressor task [23]. Furthermore, healthy participants receiving an intervention designed to increase hope demonstrated longer pain tolerance than controls [24].

Hope has been most often studied among cancer patients. However, the relationship between hope and pain is not always as clear as with optimism and pain, which may stem from a greater variety of measures employing different operational definitions to measure hope (see Table 1). In some studies hope was comparable between those with and without pain [25, 26], but in others those with higher hope had fewer pain symptoms and fatigue [27], lower pain interference [25, 28] and higher meaning ascribed to pain [26]. Of note, in one study, those with cancer pain had lower hope than those without pain [28]. Pain intensity among cancer patients has been associated with hope in some (e.g., Hsu [28]) studies and not others (e.g., Lin [25]). Furthermore, hope was not associated with pain among patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain and it was speculated that this surprising results may have been owing to a restricted range of pain scores [29].

Additional research has examined the link between self-efficacy, pain, and related outcomes, such as functional impairment and quality of life [30–33]. Self-efficacy is the belief that one has the ability to achieve a particular goal [34]. Self-efficacy beliefs for managing pain have been linked to pain and related outcomes among arthritis patients in numerous studies [35–37]. Self-efficacy may explain gender differences often observed in clinical and experimental pain responding [38]. Jackson et al. [39] found that physical and task specific self-efficacy fully mediated the link between gender and pain perception in a cold pressor task. In addition, self-efficacy accounted for a substantial amount of variance in experimental pain tolerance between marathon runners and matched controls [40]. In another study, individuals with high self-efficacy who were provided a choice of coping strategies displayed increased tolerance of acute pain and lower pain reports [41]. Overall, the current research into the relationship between positive psychological traits and pain perception provides a comprehensive picture that optimism, hope, and self-efficacy positively influence well-being and health, and that flourishing may be protective against negative health outcomes.

Pain Catastrophizing and Pain Perception

In contrast to the way that positive psychological traits often buffer pain experience, certain cognitive factors (the way one thinks about painful experiences) can heighten pain perception. Pain catastrophizing is one such cognitive factor that is a negative amplification of pain-related thoughts through rumination (repetitive thoughts about pain), magnification (exaggerated concern about negative consequences of pain), and helplessness (believing nothing will change the pain) [42]. Pain catastrophizing has been linked with pain in hundreds of studies in varied patient populations [42, 43]. Indeed, the results are maintained after controlling for depression [44] and anxiety [45]. Likewise, pain catastrophizing has been the strongest predictor of pain among other related constructs such as fear and body vigilance [46]. Pain catastrophizing has explained observed ethnic [47] and gender [48] differences in pain perception. Moreover, age differences in pain catastrophizing appear to be based on type of pain, as well as whether pain characteristics are sensory or affective [49].

Important research established the direction of the relationship between catastrophizing and pain among healthy participants, such that catastrophizing precedes increased pain response [50]. Similarly, prospective studies have demonstrated that reducing pain catastrophizing brings about lower pain and disability [42, 51]. Critically, reductions in pain catastrophizing have been achieved through cognitive behavioral interventions [52–54]. Experimental work has demonstrated that catastrophizing can be manipulated and that catastrophic thinking is linked with lower pain endurance compared with those employing positive coping self-statements [55].

Some work suggests a differential relationship between trait and state catastrophizing. Trait or general catastrophizing is assessed by asking how participants typically respond to pain, whereas state- or situation-specific catastrophizing is assessed by asking about pain response in a particular situation, such as during or following a specific experiment. In some cases, clinical and non-clinical participants differ in trait and state pain catastrophizing. Fibromyalgia (FMS) patients had greater trait catastrophizing than controls, but similar state in response to thumbnail pressure pain. Further, only in FMS patients was there a correlation between activation of the left posterior parietal cortex and state catastrophizing. This brain region is an integration center for somatosensory information [56]. Similarly, within some studies trait catastrophizing was stable across ethnicity in healthy participants, whereas some variation in situational catastrophizing exists [57]. Variation in research results across studies may stem from differences in the catastrophizing construct under examination (trait vs state). It is important that investigators be clear about what type of catastrophizing is being assessed to improve methodological consistency across the literature.

Some research has examined the possible mechanisms that explain the link between pain catastrophizing and pain perception. Higher catastrophizing during experimental pain is associated with lower activation of descending pain-inhibitory controls (DNIC), especially among women [58]. Interestingly, women also showed a lower DNIC response than men, which could help explain greater pain perception and more negative pain outcomes among women. It would be advantageous for future research to determine whether modifying pain catastrophizing affects DNIC processes [58].

A growing body of work has begun to assess the neural correlates of pain catastrophizing during the administration of noxious stimuli. Catastrophizing is linked with increased brain activity in regions associated with anticipation of pain [medial frontal cortex (MFC), cerebellum), attention to pain [dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus, rostral anterior cingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPF)], emotional aspects of pain (claustrum, closely connected to amygdala) and motor activity [44, 59]. Furthermore, pain catastrophizing is associated with different patterns of cortical response depending on the intensity of the pain [59]. Specifically, during moderate as opposed to mild pain, pain catastrophizing is linked with lower activity in the DLPF and MFC—regions of the brain responsible for top-down pain suppression [59].

Among individuals with major depressive disorder and not in healthy controls the helplessness subscale of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (see Table 1) was related to activation of the right amygdala during the anticipation of pain [60]. This brain region has been found to be associated with passive coping styles. Other recent research demonstrated that pain catastrophizing is related to phantom limb pain in upper limb amputees. Further, using electroencephalography, associations between pain catastrophizing and N/P135 dipole located in the area around the secondary somatosensory cortex were found. This area is predominately related to discriminative and affective-motivational aspects of human pain processing [61•]. In addition, temporal summation, a marker of central pain facilitation, has also been linked with pain catastrophizing [58]. This validates psychological approaches that seek to modify attentional focus, interpretation, and emotional processes surrounding pain as are often found in cognitive behavioral therapy [62].

Some research has demonstrated that positive psychological traits, such as self-efficacy, can also act as mediators between catastrophizing and pain and catastrophizing and pain-related outcomes [63, 64]. The belief in one’s ability to control pain fully mediated the link between pain catastrophizing and pain among osteoarthritis patients, while perceptions of ability for physical functions fully explained the relationship between pain catastrophizing and physical disability [64]. Indeed, the belief in one’s ability for dealing with emotional symptoms of arthritis partially explained the link between pain catastrophizing and psychological disability. In a similar study, beliefs about the ability to cope with arthritis symptoms partially explained the relationship between pain catastrophizing and physical functioning among osteoarthritis patients [63]. All of these studies highlight the importance of understanding pain catastrophizing, as it appears critical in determining pain experience. This promising body of research indicates that understanding whom, why, and when individual’s catastrophize, and that recognizing possible neural mechanisms involved will give a better insight into pain perception.

Positive Traits and Pain Catastrophizing

Ample research has linked pain catastrophizing with negative psychological experiences, such as depression, anxiety, and fear [44, 45, 65–69]. Pain catastrophizing fully mediated the relationship between pain and emotional distress among 46 back pain outpatients [70]. Furthermore, pain catastrophizing has explained the link between pre-surgical anxiety and post-surgical pain [71]. Given the positive relationship between pain catastrophizing and negative psychological experiences it stands to reason that pain catastrophizing would be linked inversely with positive psychological qualities. Those with higher levels of positive traits such as optimism [72•, 73•], hope [73•, 74], and self-efficacy [63, 64, 75] are, in fact, less likely to engage in pain catastrophizing. Furthermore, positive emotions and resiliency are associated with lower pain catastrophizing [76].

The inverse relationship between positive traits and pain catastrophizing might be understood in the context of the link between positive traits and mental health. Positive traits such as hope [77] and self-efficacy [75] are associated inversely with negative psychological sequelae, such as depression. Individuals high in hope have been found to cope better with daily stress and negative emotions, whereas those low in hope have shown stronger stress reactions and poorer emotional recovery [78]. In predicting future outcomes, it has also been demonstrated that hope can act as a resiliency factor. Those higher in hope have lower future levels of depression and anxiety than those with low in hope [79]. Further, among patients with depression, those with higher levels of optimism experience better coronary artery bypass surgery treatment outcomes [80].

Individuals who possess higher levels of positive traits, such as hope or optimism, are more likely to experience higher levels of positive emotions. Hope and optimism are thinking processes about the pursuit of a goal, and higher levels can create “a sense of affective zest” [22]. Correspondingly, those who experience greater levels of positive emotions possess higher resilience, which equips them to confront difficult experiences, which could include pain [81, 82]. Experimental studies have demonstrated that positive emotions counteract negative emotions [82]. Participants underwent a negative emotion induction by preparing for a time-pressured speech. Then they were assigned randomly to films, which induced either positive, negative, or neutral emotions. Those who experienced positive emotions following the stressful task experienced faster cardiovascular recovery, suggesting the health benefits of positive emotions, which should, theoretically, extend to pain.

Link Between Positive Traits, Pain Catastrophizing, and Pain Perception

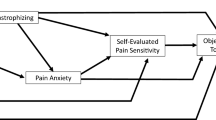

Although there is accumulating evidence about positive traits, pain catastrophizing, and pain perception, it was only recently that research established that the link between positive traits and pain perception operates through pain catastrophizing (see Fig. 1). The first study to demonstrate this link sampled a healthy community sample of 114 men and women [73•]. Both trait hope and optimism were associated inversely with pain response in a cold pressor task. All three dimensions of pain catastrophizing (rumination, magnification, and helplessness) partially mediated the link between hope and optimism with pain perception in independent models. Since then, this study has been replicated with a sample of 140 osteoarthritis patients and expanded upon by using a different pain stimulus (heat), a different measure of pain catastrophizing coping strategies questionnaire (CSQ), and temporal summation as an outcome measure, which reflects central pain facilitation [72•]. Similar to previous research, those with higher levels of optimism displayed lower temporal summation, which indicates less pain facilitation. In addition, pain catastrophizing was a significant mediator of the link between optimism and temporal summation.

The consistent results in correlational analyses have led to an investigation into whether positive traits could be related causally to experimental pain. Hanssen et al. [83••] addressed this question by manipulating optimism experimentally. They demonstrated a causal link between optimism and pain perception. Healthy participants were assigned randomly to visualization and writing about a future best possible self to induce optimism, or visualization and writing about a typical day (control). Participants then completed the cold pressor task with a visual analog scale measure of pain perception taken at intervals throughout the task, as well as a post-measure. Those in the optimism condition consistently reported lower pain throughout the cold pressor task. Consistent with prior research, situational pain catastrophizing mediated the relationship between optimism and pain [83••]. This study demonstrates that optimism can not only be modified, but that doing so diminishes the experience of pain.

Practice Implications

It is recommended that psychological approaches to pain reduction include a focus on reducing pain catastrophizing and increasing thoughts, feelings, and behaviors associated with positive traits, such as hope, optimism, and self-efficacy. Cognitive behavioral interventions are the most widely used approaches for modifying pain catastrophizing and have proven effective in multiple studies [52–55]. Psychological treatment often involves multiple sessions over several months to achieve sustained treatment outcomes [52]. Modifying catastrophizing may include activities such as examining automatic thoughts, restructuring unhelpful thoughts, planning, and positive-self-talk [53].

Briefer cognitive behavioral interventions have also proven effective for modifying pain catastrophizing and reducing experimental pain [54]. A manualized protocol included instruction in three strategies for reducing catastrophic thinking: distraction, mindfulness and acceptance, and cognitive restructuring. Researchers provided examples of distraction and mindfulness/acceptance. Cognitive restructuring was taught by an interactive discussion lasting approximately 5 mins of how to examine a thought and reframe it in a more helpful or realistic way. Then, participants practiced restructuring thoughts with assistance from a trained research assistant as needed. The entire intervention lasted approximately 10 mins and was effective in reducing pain catastrophizing, increasing pain tolerance, and reducing subjective pain report [54]. Given evidence that brief cognitive interventions may be associated with changes in future coping behaviors [84], it is necessary for prospective studies to try to determine the long-term effects of brief interventions.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) [85] is another successful approach for the treatment of pain [86]. In contrast to traditional cognitive behavioral approaches, the focus of ACT is on committing to pursuing valued activities without trying to avoid or control pain. A goal is to improve psychological flexibility and reduce the effect of pain on functioning [87]. There is evidence that pain acceptance is linked with better adjustment among chronic pain patients [88] and that acceptance-based coping is a stronger predictor of adjustment than control-based coping [89]. Furthermore, the benefits of pain acceptance coping on activity have been demonstrated prospectively [90]. The link between pain intensity and fear about pain among patients with chronic pain was less strong among those with higher acceptance [91], suggesting a protective role of acceptance in the negative emotional sequelae of pain. Furthermore, patients who increase acceptance of pain show decreased pain anxiety, which is linked with better treatment outcomes [92].

Acceptance has been increased successfully through brief coping instructions in laboratory settings involving shifting attention and focus [93]. Furthermore, the teaching of acceptance and commitment through experiential activities and metaphors is associated with a variety of adaptive treatment outcomes [93]. Acceptance of pain and commitment to pursuing valued activities may be viewed a marker of resilience [94•]. Similarly, dispositional optimism is often viewed as a source of an individual’s resilience [94•], and the experience of positive emotions plays a significant role in promoting mental activities and fostering experiences that build resilience [82]. Given that both acceptance and positive emotions are conceptualized as forms of resilience, and that they both play a prominent role in pain perception and pain catastrophizing, it would be advantageous if future research and therapeutic interventions assessed these resilience mechanisms together.

Much research has shown that mood can be manipulated and that interventions targeted to increase positive traits translate to improved experimental pain outcomes. Positive mood inductions include activities such as showing clips from humorous films or brief stories that invoke positive feelings, such as joy, are associated with better pain tolerance and reduced pain perception [95, 96]. Advising patients to engage with media containing humorous or other positive emotional content could yield benefits in a variety of contexts. In an acute situation, such as prior to undergoing a medical procedure, a humorous video clip could be shown or an inspirational story could be read. In chronic situations, such as a prolonged illness or injury, a regimen containing “infusions” of positive emotions throughout the day in either regular or variable intervals could be implemented. Non-media-based approaches, such as journaling for increasing positive emotions, such as gratitude, have also proven effective [97, 98], and may be useful in situations where using technology is not feasible or appropriate.

Brief interventions targeting positive traits have also been effective in improving experimental pain outcomes among healthy participants. An intervention to increase hope consisted of a structured 16-min session. The session included: (i) guided imagery—instruction to think of a desired goal and build motivation and strategies to accomplish the goal, and considered how the experience might help in achieving future goals and dialogue; and (ii) a discussion of why the identified goal is important and verbalization of the material visualized in the previous step. Next, there was a strategies instruction, which provided information on how to increase goal-directed thinking, pathways thinking, and agency, with tips translating this general information for use on the cold pressor task. Finally, they completed a worksheet with instructions to write about another experience in pursuing goals, listing positive self-talk statements and strategies for the cold pressor task, and providing an estimate of expected pain tolerance time. This intervention was successful and individuals in the hope treatment condition experienced significantly longer tolerance in the cold pressor task than those in the control group [24]. Future work to test this protocol with pain patients is recommended.

A brief intervention to increase optimism using a best possible self-activity that included writing and visualization has also proven successful [83••]. Participants were instructed to think about their best possible self for 1 min, then to write about this topic for 15 mins, and, finally, to imagine the story they recorded vividly for 5 mins. This approach has been used successfully to increase optimism in previous studies [99, 100]. Those in the best possible self-condition experienced a change in expectations for future outcomes and reported correspondingly lower pain intensity during a cold pressor task compared with those in the control group [83••]. Extending this approach to clinical pain patients and observing long-term outcomes would be valuable.

Approaches to increase self-efficacy often provide education or coping skills [101]. It has been suggested that approaches for improving self-efficacy should increase their use of technology [101]. This is especially important for patients who work full-time or have other time restrictions, which may pose barriers to regular clinic visits over a sustained period of time [101]. Online dissemination of positive psychology exercises has proven feasible and effective [102].

Conclusion

The benefit of high levels of the positive personality traits optimism, hope, and self-efficacy has been demonstrated in clinical and healthy populations exposed to pain. Further, these traits provide a protective influence for pain perception. Conversely, certain cognitive factors (the way one thinks about painful experiences) can be maladaptive and negatively influence pain perception. Pain catastrophizing is a well-established risk factor for increased pain perception and there are numerous neurological studies that have revealed activity in brain regions associated with pain control and integration, which provides support for this relationship. Ample research has linked pain catastrophizing with negative psychological experiences, such as depression and anxiety. Foremost for this review, a corresponding, but smaller, body of research demonstrates the inverse relationship between pain catastrophizing and the positive traits of optimism, hope, and self-efficacy. Recent research has provided an integrated psychological model examining positive traits and pain catastrophizing together to understand pain perception. Specifically, lower levels of pain catastrophizing explain the inverse link between positive traits and pain perception. These basic science approaches answer fundamental questions that can be translated into evidence-based treatments. Practice implications for reducing pain perception include a focus on cognitive behavioral strategies for improving levels of hope, optimism, and self-efficacy, and reducing pain catastrophizing. It will be important for future research to determine whether there is a causal link between positive traits and pain catastrophizing. Understanding whether increasing positive traits reduces catastrophizing or whether reducing catastrophizing increases positive traits will provide direction in crafting psychological interventions to reduce the experience of pain.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Gatchel RJ, Peng YB, Peters ML, et al. The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain: scientific advances and future directions. Psychol Bull. 2007;133:581–624.

Sullivan MJL, Rodgers WM, Kirsch I. Catastrophizing, depression and expectancies for pain and emotional distress. Pain. 2001;91:147–54.

Salovey P, Rothman AJ, Detweiler JB, Steward WT. Emotional states and physical health. Positive psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. p. 110–21.

Pressman SD, Cohen S. Does positive affect influence health? Psychol Bull. 2005;131:925–71.

Seligman MEP, Csikszentmihalyi M. Positive psychology: an introduction. Positive psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2000. p. 5–14.

Keyes CLM. Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: a complementary strategy for improving national mental health. Am Psychol. 2007;62:95–108.

Rasmussen HN, Scheier MF, Greenhouse JB. Optimism and physical health: a meta-analytic review. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:239–56.

Scheier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping, and health: assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychol. 1985;4:219–47.

Kurtz ME, Kurtz JC, Given CW, Given BA. Patient optimism and mastery-do they play a role in cancer patients' management of pain and fatigue? J Pain Symptom Manag. 2008;36:1–10.

Wong WS, Fielding R. Quality of life and pain in Chinese lung cancer patients: is optimism a moderator or mediator? Qual Life Res. 2007;16:53–63.

Pence L, Valrie CR, Gil KM, et al. Optimism predicting daily pain medication use in adolescents with sickle cell disease. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2007;33:302–9.

Ferreira VM, Sherman AM. The relationship of optimism, pain and social support to well-being in older adults with osteoarthritis. Aging Mental Health. 2007;11:89–98.

Sipila K, Ylostalo PV, Ek E, et al. Association between optimism and self-reported facial pain. Acta Odontol Scand. 2006;64:177–82.

Costello NL, Bragdon EE, Light KC, et al. Temporomandibular disorder and optimism: relationships to ischemic pain sensitivity and interleukin-6. Pain. 2002;100:99–110.

Powell R, Johnston M, Smith WC, et al. Psychological risk factors for chronic post-surgical pain after inguinal hernia repair surgery: a prospective cohort study. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:600–10.

Rosenberger PH, Kerns R, Jokl P, Ickovics JR. Mood and attitude predict pain outcomes following arthroscopic knee surgery. Ann Behav Med. 2009;37:70–6.

Mahler HM, Kulik JA. Optimism, pessimism and recivery from coronary bypass surgery: prediction of affect, pain, and functional status. Psychol Health Med. 2000;5:347–58.

Geers AL, Wellman JA, Fowler SL, et al. Dispositional optimism predicts placebo analgesia. J Pain. 2010;11:1165–71.

Morton DL, Watson A, El-Deredy W, Jones AKP. Reproducibility of placebo analgesia: effect of dispositional optimism. Pain. 2009;146:194–8.

Geers AL, Wellman JA, Helfer SG, et al. Dispositional optimism and thoughts of well-being determine sensitivity to an experimental pain task. Ann Behav Med. 2008;36:304–13.

Goodin BR, Kronfli T, King CD, et al. Testing the relation between dispositional optimism and conditioned pain modulation: does ethnicity matter? J Behav Med. Epub ahead of print 25 Feb 2012 Feb.

Snyder CR. Hope theories: rainbows in the mind. Psychol Inq. 2002;13(4):249–75.

Snyder CR, Berg C, Woodward JT, et al. Hope against the cold: individual differences in trait hope and acute pain tolerance on the cold pressor task. J Pers. 2005;73:287–312.

Berg CJ, Snyder CR, Hamilton N. The effectiveness of a hope intervention in coping with cold pressor pain. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:804–9.

Lin C-C, Lai Y-L, Ward SE. Effect of cancer pain on performance status, mood states, and level of hope among Taiwanese cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2003;25:29–37.

Chen ML. Pain and hope in patients with cancer: a role for cognition. Cancer Nurs. 2003;26:61–7.

Berendes D, Keefe FJ, Somers TJ, et al. Hope in the context of lung cancer: relationships of hope to symptoms and psychological distress. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2010;40:174–82.

Hsu TH, Lu MS, Tsou TS, Lin CC. The relationship of pain, uncertainty, and hope in Taiwanese lung cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manag. 2003;26:835–42.

Wright MA, Wren AA, Somers TJ, et al. Pain acceptance, hope, and optimism: relationships to pain and adjustment in patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain. J Pain. 2011;12:1155–62.

Focht BC, Rejeski WJ, Ambrosius WT, et al. Exercise, self-efficacy, and mobility performance in overweight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;53:659–65.

Maly MR, Costigan PA, Olney SJ. Determinants of self efficacy for physical tasks in people with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;55:94–101.

Marks R, Allegrante JP, Lorig K. A review and synthesis of research evidence for self-efficacy-enhancing interventions for reducing chronic disability: implications for health education practice (Part I). Health Promot Pract. 2005;6:37–43.

Sharma L, Cahue S, Song J, et al. Physical functioning over three years in knee osteoarthritis: role of psychosocial, local mechanical, and neuromuscular factors. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:3359–70.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215.

Pariser D, O'Hanlon A. Effects of telephone intervention on arthritis self-efficacy, depression, pain, and fatigue in older adults with arthritis. J Geriatr Phys Ther. 2005;28:67–73.

Somers TJ, Shelby RA, Keefe FJ, et al. Disease severity and domain-specific arthritis self-efficacy: relationships to pain and functioning in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 2010;62:848–56.

Pells JJ, Shelby RA, Keefe FJ, et al. Arthritis self-efficacy and self-efficacy for resisting eating: relationships to pain, disability, and eating behavior in overweight and obese individuals with osteoarthritic knee pain. Pain. 2008;136:340–7.

Fillingim RB, King CD, Ribeiro-Dasilva MC, et al. Sex, gender, and pain: a review of recent clinical and experimental findings. J Pain. 2009;10:447–85.

Jackson T, Iezzi T, Gunderson J, et al. Gender differences in pain perception: the mediating role of self-efficacy beliefs. Sex Roles. 2002;47:561–8.

Johnson MH, Stewart J, Humphries SA, Chamove AS. Marathon runners reaction to potassium iontophoretic experimental pain: pain tolerance, pain threshold, coping and self-efficacy. Eur J Pain. 2012;16:767–74.

Rokke PD, Fleming-Ficek S, Siemens NM, Hegstad HJ. Self-efficacy and choice of coping strategies for tolerating acute pain. J Behav Med. 2004;27:343–60.

Sullivan MJL. The pain catastrophzing scale user manual. Montreal: McGill University; 2009.

Quartana PJ, Campbell CM, Edwards RR. Pain catastrophizing: a critical review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2009;9:745–58.

Gracely RH, Geisser ME, Giesecke T, et al. Pain catastrophizing and neural responses to pain among persons with fibromyalgia. Brain. 2004;127:835–43.

Granot M, Ferber SG. The roles of pain catastrophizing and anxiety in the prediction of postoperative pain intensity: a prospective study. Clin J Pain. 2005;21:439–45.

Sorbi MJ, Peters ML, Kruise DA, et al. Electronic momentary assessment in chronic pain i: psychological pain responses as predictors of pain intensity. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:55–66.

Hsieh AY, Tripp DA, Ji L-J, Sullivan MJL. Comparisons of catastrophizing, pain attitudes, and cold-pressor pain experience between Chinese and European Canadian young adults. J Pain. 2010;11:1187–94.

Keefe FJ, Lefebvre JC, Egert JR, et al. The relationship of gender to pain, pain behavior and disability in osteoarthritis patients: the role of catastrophizing. Pain. 2000;87:325–34.

Ruscheweyh R, Nees F, Marziniak M, et al. Pain catastrophizing and pain-related emotions: influence of age and type of pain. Clin J Pain. 2011;27:578–86.

Campbell CM, Quartana PJ, Buenaver LF, et al. Changes in situation-specific pain catastrophizing precede changes in pain report during capsaicin pain: a cross-lagged panel analysis among healthy, pain-free participants. J Pain. 2010;11:876–84.

Adams H, Ellis T, Stanish WD, Sullivan MJL. Psychosocial factors related to return to work following rehabilitation of whiplash injuries. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17:305–15.

Smeets RJ, Vlaeyen JW, Kester AD, Knottnerus JA. Reduction of pain catastrophizing mediates the outcome of both physical and cognitive-behavioral treatment in chronic low back pain. J Pain. 2006;7:261–71.

Thorn BE, Pence LB, Ward LC, et al. A randomized clinical trial of targeted cognitive behavioral treatment to reduce catastrophizing in chronic headache sufferers. J Pain. 2007;8:938–49.

Stonerock Jr GL. The utility of brief cognitive skills training in reducing pain catastrophizing during experimental pain. Chapel Hill, NC: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2012.

Roditi D, Robinson ME, Litwins N. Effects of coping statements on experimental pain in chronic pain patients. J Pain Res. 2009;2009:109–16.

Burgmer M, Petzke F, Giesecke T, et al. Cerebral activation and catastrophizing during pain anticipation in patients with fibromyalgia. Psychosom Med. 2011;73:751–9.

Fabian LA, McGuire L, Goodin BR, Edwards RR. Ethnicity, catastrophizing, and qualities of the pain experience. Pain Med. 2011;12:314–21.

Goodin BR, McGuire L, Allshouse M, et al. Associations between catastrophizing and endogenous pain-inhibitory processes: sex differences. J Pain. 2009;10:180–90.

Seminowicz DA, Davis KD. Cortical responses to pain in healthy individuals depends on pain catastrophizing. Pain. 2006;120:297–306.

Strigo IA, Simmons AN, Matthews SC, et al. Association of major depressive disorder with altered functional brain response during anticipation and processing of heat pain. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:1275–84.

• Vase L, Egsgaard LL, Nikolajsen L, et al. Pain catastrophizing and cortical responses in amputees with varying levels of phantom limb pain: a high-density EEG brain-mapping study. Exp Brain Res. 2012;218:407–17. Demonstrated cortical responses to acute stimuli associated with attentional processes relevant to pain catastrophizing.

Michael ES, Burns JW. Catastrophizing and pain sensitivity among chronic pain patients: moderating effects of sensory and affect focus. Ann Behav Med. 2004;27:185–94.

McKnight PE, Afram A, Kashdan TB, et al. Coping self-efficacy as a mediator between catastrophizing and physical functioning: treatment target selection in an osteoarthritis sample. J Behav Med. 2010;33:239–49.

Shelby RA, Somers TJ, Keefe FJ, et al. Domain specific self-efficacy mediates the impact of pain catastrophizing on pain and disability in overweight and obese. J Pain. 2008;9:912–9.

Borsbo B, Peolsson M, Gerdle B. Catastrophizing, depression, and pain: correlation with and influence on quality of life and health - a study of chronic whiplash associated disorders. J Rehabil Med. 2008;40:562–9.

Drahovzal DN, Stewart SH, Sullivan MJL. Tendency to catastrophize somatic sensations: pain catastrophizing and anxiety sensitivity in predicting headache. Cogn Behav Ther. 2006;35:226–35.

Edwards RR, Smith MT, Kudel I, Haythornthwaite J. Pain-related catastrophizing as a risk factor for suicidal ideation in chronic pain. Pain. 2006;126:272–9.

Leeuw M, Goossens MEJB, Linton SJ, et al. The fear-avoidance model of musculoskeletal pain: current state of scientific evidence. J Behav Med. 2007;30:77–94.

Willoughby SG, Hailey BJ, Mulkana S, Rowe J. The effect of laboratory-induced depressed mood state on responses to pain. Behav Med. 2002;28:23–31.

Moldovan AR, Onac IA, Vantu M, et al. Emotional distress, pain catastrophizing and expectancies in patients with low back pain. J Cogn Behav Psychother. 2009;9:83–93.

Pinto PR, McIntyre T, Almeida A, Araújo-Soares V. The mediating role of pain catastrophizing in the relationship between presurgical anxiety and acute postsurgical pain after hysterectomy. Pain. 2012;153:218–26.

• Goodin BR, Glover TL, Sotolongo A, et al. The association of greater dispositional optimism with less endogenous pain facilitation is indirectly transmitted through lower levels of pain catastrophizing. J Pain. 2013;14:126–35. Documented the link between higher optimism, lower pain catastrophizing, and lower pain in a clinical sample.

• Hood A, Pulvers K, Carrillo J, et al. Positive traits linked to less pain through lower pain catastrophizing. Personal Individ Differ. 2012;52:401–5. First study to document that the link between higher optimism and hope with lower pain perception operates through lower pain catastrophizing.

Smedema SM, Catalano D, Ebener DJ. The relationship of coping, self-worth, and subjective well-being: a structural equation model. Rehabil Counsel Bull. 2010;53:131–42.

Lumley MA, Smith JA, Longo DJ. The relationship of alexithymia to pain severity and impariment among patients with chronic myofascial pain: comparisons with self-efficacy, catastrophizing and depression. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:823–30.

Ong AD, Zautra AJ, Reid MC. Psychological resilience predicts decreases in pain catastrophizing through positive emotions. Psychol Aging. 2010;25:516–23.

Hartley SM, Vance DE, Elliott TR, et al. Hope, self-efficacy, and functional recovery after knee and hip replacement surgery. Rehabil Psychol. 2008;53:521–9.

Ong AD, Edwards LM, Bergeman CS. Hope as a source of resilience in later adulthood. Personal Individ Differ. 2006;41:1263–73.

Arnau RC, Rosen DH, Finch JF, et al. Longitudinal effects of hope on depression and anxiety: a latent variable analysis. J Pers. 2007;75:43–63.

Tindle H, Belnap BH, Houck PR, et al. Optimism, response to treatment of depression, and rehospitalization after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Psychosom Med. 2012;74:200–7.

Cohn MA, Fredrickson BL, Brown SL, et al. Happiness unpacked: positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion. 2009;9:361–8.

Fredrickson BL. The role of positive emotions in positive psychology. The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am Psychol. 2001;56:218–26.

•• Hanssen MM, Peters ML, Vlaeyen JW, et al. Optimism lowers pain: evidence of the causal status and underlying mechanisms. Pain. 2013;154:53–8. First study to demonstrate a causal link between higher optimism and lower pain perception.

Tsao JC, Fanurik D, Zeltzer LK. Long-term effects of a brief distraction intervention on children's laboratory pain reactivity. Behav Modif. 2003;27:217–32.

Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and commitment therapy: an experiential approach to behavior change. New York: Guilford Press; 1999.

Wetherell JL, Afari N, Rutledge T, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain. 2012;152:2098–107.

Thompson M, McCracken LM. Acceptance and related processes in adjustment to chronic pain. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2011;15:144–51.

Reneman MF, Dijkstra A, Geertzen JHB, Dijkstra PU. Psychometric properties of chronic pain acceptance questionnaires: a systematic review. Eur J Pain. 2010;14:457–65.

McCracken LM, Vowles KE, Gauntlett-Gilbert J. A prospective investigation of acceptance and control-oriented coping with chronic pain. J Behav Med. 2007;30:339–49.

Cho S, McCracken LM, Heiby EM, et al. Pain acceptance-based coping in complex regional pain syndrome Type I: daily relations with pain intensity, activity, and mood. J Behav Med. Epub ahead of print 2 Aug 2012.

Crombez G, Viane I, Eccleston C, et al. Attention to pain and fear of pain in patients with chronic pain. J Behav Med. Epub ahead of print 22 May 2012.

Huggins JL, Bonn-Miller MO, Oser ML, et al. Pain anxiety, acceptance, and outcomes among individuals with HIV and chronic pain: a preliminary investigation. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50:72–8.

Ruiz FJ. A review of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) empirical evidence: correlational, experimental psychopathology, component and outcome studies. Int J Psychol Psychol Ther. 2010;10:125–62.

• Sturgeon JA, Zautra AJ. Psychological resilience, pain catastrophizing, and positive emotions: perspectives on comprehensive modeling of individual pain adaptation. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2013;17:317. Review article on psychological vulnerability and resilience factors associated with pain response.

Loggia ML, Mogil JS, Bushnell MC. Experimentally induced mood changes preferentially affect pain unpleasantness. J Pain. 2008;9:784–91.

Meagher MW, Arnau RC, Rhudy JL. Pain and emotion: effects of affective picture modulation. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:79–90.

Seligman MEP, Steen TA, Park N, Peterson C. Positive psychology progress: empirical validation of interventions. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005. p. 410–21.

Emmons RA, McCullough ME. Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:377–89.

Meevissen YMC, Peters ML, Alberts HJEM. Become more optimistic by imagining a best possible self: effects of a two week intervention. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2011;42:371–8.

Peters ML, Flink IK, Boersma K, Linton SJ. Manipulating optimism: can imagining a best possible self be used to increase positive future expectancies? J Posit Psychol. 2010;5:204–11.

Somers TJ, Wren AA, Shelby RA. The context of pain in arthritis: self-efficacy for managing pain and other symptoms. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:502–8.

Schueller SM, Parks AC. Disseminating self-help: positive psychology exercises in an online trial. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14:e63.

Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1994;67:1063–78.

Lorig K, Chastain RL, Ung E, et al. Development and evaluation of a scale to measure perceived self-efficacy in people with arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1989;32:37–44.

Nicholas MK. Self-efficacy and chronic pain. St Andrews: British Psychological Society; 1989.

Schwarzer R, Jerusalem M. Generalized self-efficacy scale. In: Weinman J, Wright S, Johnston M, editors. Measures in health psychology: a user's portfolio causal and control beliefs. Windsor: Nfer-Nelson; 1995. p. 35–7.

Snyder CR, Harris C, Anderson JR, et al. The will and the ways: development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;60:570–85.

Snyder CR, Sympson SC, Ybasco FC, et al. Development and validation of the State Hope Scale. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70:321–35.

Herth K. Abbreviated instrument to measure hope: development and psychometric evaluation. J Adv Nurs. 1992;17:1251–9.

Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7:524–32.

Rosenstiel AK, Keefe FJ. The use of coping strategies in chronic low back pain patients: relationship to patient characteristics and current adjustment. Pain. 1983;17:33–44.

Conflict of Interest

Kim Pulvers declares she has no conflict of interest.

Anna Hood declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Psychiatric Management of Pain

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pulvers, K., Hood, A. The Role of Positive Traits and Pain Catastrophizing in Pain Perception. Curr Pain Headache Rep 17, 330 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-013-0330-2

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11916-013-0330-2