Abstract

Worldwide prevalence of dementia is predicted to double every 20 years. The most common cause in individuals over 65 is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but in those under 65, frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is as frequent. The physical and cognitive decline that characterizes these diseases is commonly accompanied by troublesome behavioral symptoms. These behavioral symptoms contribute to significant morbidity and mortality among both patients and caregivers. Medications have been largely ineffective in managing these symptoms and carry significant adverse effects. Non-pharmacological interventions have been recommended to precede the utilization of pharmacological treatments. This article reviews the research about these interventions with special attention to the variations by etiology, especially FTD. The authors offer recommendations for improving utilization of these strategies and future research recommendations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In 2010, the worldwide prevalence of dementia was estimated to be 35.6 million with a doubling predicted every 20 years [1]. The most common cause for dementia in individuals over 65 is Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but for those less than 65, frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is as frequent as AD [2, 3]. The physical and cognitive decline that characterizes these diseases is accompanied by symptoms that affect behavior and personality, occurring in 61–98 % of those with dementia sometime during the trajectory of their illness. [4–6]. In FTD, these behavioral symptoms are often the presenting symptom and a hallmark of the disease [7, 8]. Referred to as neuropsychiatric symptoms (NPS) or Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia (BPSD), they include sleep disruption, irritability, apathy, and mood and psychotic symptoms. There is increasing evidence that prevalence of these behaviors varies with the type of dementia although the specific profiles are inconsistent across studies [4, 9–12]. Research has linked the specific anatomical and chemical changes associated with differing pathologies to specific behaviors.

Regardless of etiology, behavioral symptoms are challenging for family caregivers and result in considerable consequences including caregiver burden and stress [13, 14] increased risk for placement [15–17] and significant cost to the health care system [18, 19]. Some data report that caregivers of people with FTD and dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) are particularly burdened by behavioral symptoms [20, 21]. FTD caregivers specifically report a loss of emotional attachment leading to isolation and anger due to behavioral symptoms [22]. Medication therapies have not proven effective in managing these symptoms and in fact, have significant adverse effects and risks [23–25]. Non-pharmacological strategies include interventions that target environmental adaptations, behavioral strategies, caregiver training, and education and have been recommended to precede consideration of pharmacological therapies [26, 27]. A meta-analysis suggested that interventions that use a non-pharmacological approach were more likely to be effective in managing these behavioral symptoms [28]. A more recent meta-analysis of 23 trials concluded significant benefits for interventions targeting both patient and caregiver that suggest they are comparable in efficacy to the use of antipsychotics with fewer risks [29••]. However, attention to specific etiologies has not been well studied, and in fact, only case studies and small series have been published in FTD. The purpose of this paper is to review the current literature regarding these symptoms and management strategies in community dwelling individuals with attention particularly to FTD.

Causes and Etiology

Anatomy

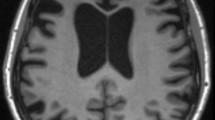

Neuropsychiatric symptoms in the dementia syndromes reflect the changes in the diseased brain. Anatomical changes related to neurodegeneration, pathology burden, hypometabolism and changes in neurotransmitters are all responsible for the observed clinical symptoms. A table of affected regions and corresponding symptoms in various syndromes are listed in Table 1. In general, disease in the left hemisphere (dominant) may produce more awareness of deficits, depression, and anxiety. Changes in the right hemisphere are associated with poorer insight into symptoms. The changes in behavior and personality seen in dementia are often associated with loss of function among various structures in the frontal and temporal lobes. Four behaviors: apathy, disinhibition, eating disorders, and aberrant motor behavior have been correlated with tissue loss in specific regions in the right frontal lobe [30].

In addition to anatomical substrates, disruptions in the serotonergic and cholinergic systems (5HT dysfunction) are linked to behavioral changes in AD along with a variety of other neurotransmitter systems including noradrenergic, dopaminergic, and glutamatergic [31]. The monoaminergic and glutamatergic systems have also been proposed to play a role in the modulation of behaviors in dementia patients [32•]. In FTD, pre- and postsynaptic changes in serotonin occur, and these changes may play a role in the behavioral disorders of this disease [33]. Although many symptoms may be anatomically specific, the disruption of circuits and networks in the brains of affected patients may produce behavioral symptoms associated with regions far from the areas of tissue loss [34]. These circuits include the dorsolateral circuit (which mediates aspects of executive function), the pre-prefrontal basal ganglia (responsible for motivation), and the orbitofrontal circuit (inhibition and social appropriateness) [32•].

Recent advances regarding the genetics of FTD have further expanded knowledge in the field, particularly genetic forms of the disease. Delusions as a presenting neuropsychiatric manifestation were more common in FTD patients who were C9ORF72 (C9) gene carriers [35]. In addition to psychosis, other psychiatric manifestations at onset of disease are seen in C9 carriers and also carriers of the granulin (GRN) gene, including bipolar presentations and compulsive disorders [36•]. While some symptoms may directly correlate to a specific brain region, the behavioral manifestations of dementia syndromes remain a complex of patient factors, environmental influences, and caregiver adaptation.

Theoretical Models

Theoretical models have been used to guide the understanding of dementia-related behaviors. These models provide a rationale for why behaviors occur and have been used to direct clinical care, caregiver training, and research in a variety of settings (nursing home, day program, and home). The Unmet Needs Model proposes that problematic behaviors result when the environment and/or the caregiver are not supportive of the person’s changing functional deficits and diminished ability to communicate [37]. For example, agitation occurs when the person is bored and cannot communicate his or her need for activity. Repetitive vocalizations may represent pain and discomfort in a patient that can no longer express the sensation of pain via typical speech [38]. The Progressively Lowered Stress Threshold (PLST) model suggests that dementia-related behaviors arise when cognitive deficits disrupt the person’s interpretation of the environment [39]. Thus, when environmental demands exceed the person’s cognitive abilities, stress manifests as behaviors such as agitation, nighttime sleep disruption, and combativeness. The PLST promotes the need for coherence between environmental demands and patient’s abilities [40]. A comprehensive, conceptual model encompassing the interaction of these factors and how they relate to symptoms and approach has recently been proposed and will be discussed in greater detail below [27].

Assessment

Tools

Formal tools have been validated to assess behavioral symptoms in dementia and can be helpful in ensuring that a comprehensive inventory of behaviors is obtained in a consistent manner. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) uses an informant interview to determine the presence of 12 common behavioral symptoms in dementia and includes frequency, severity, and level of distress to the caregiver [41]. A shortened version has been validated, and there have been modifications for use in a nursing home, self-completion by a caregiver, and recently, one by clinician assessment without caregiver interview [42–44]. The BEHAVE—AD scale is another well-validated tool which specifically targets the behavioral symptoms associated with AD [45, 46]. Because these tools were developed to focus on symptoms associated with memory deficits, they have been modified to better reflect the changes characteristic in FTD and include the modified Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) scale [47] and the FTD rating scale [48]. There are also tools that target a particular behavior such as agitation or apathy and can be helpful in developing a logical and targeted approach to a very specific symptom. A recent meta-analysis can be used to identify well-validated general and targeted measures according to behavior, setting, and time [49].

Framework

Once a behavioral symptom is identified, the use of a standardized framework allows the assessment and management plan to be comprehensive and targeted to the patient’s individual situation. The ABC model first described by Buckwalter [50] has been the most commonly used. This model focuses on the identification of trigger(s) or events thought to be causing the behavior and the consequences or responses that may improve or worsen the symptoms. It has been used to guide the development of protocols to train caregivers to manage the NPS associated with dementia [51] and is recommended in FTD [52]. This approach has been further refined with the DICE model (Describe, Investigate, Create, and Evaluate) and reflects consensus by an expert panel, of the approach once a problematic behavior has been identified [27]. The steps include a description of the behavior (D) that includes timing, location, people involved, and detailed characteristics of the behavior. Investigation of causes (I) addresses the patient, caregiver, and environmental factors involved and includes medical sources that should be ruled out especially in an acute onset where they are commonly implicated [53, 54]. Creating a plan (C) involves development of targeted strategies to address the behavior and underlying causes. Finally, evaluation of efficacy (E) is ongoing and includes being mindful to set realistic goals, perhaps reducing rather than eliminating some behaviors.

Non-pharmacological Strategies

The overall aim of using non-pharmacological strategies includes prevention of problematic behaviors, behavior symptom relief, and a lessening of caregiver distress [55]. Several professional organizations have suggested that drug therapy should be used only after the failure of non-pharmacological strategies or in cases of grave danger or distress [26, 54, 56] and that these strategies should be specifically targeted to stage of dementia [57]. For the purpose of discussion, we have divided these strategies into categories of environmental, caregiver, and behavioral approaches.

Environmental Approaches

These strategies target the etiology of behaviors as patients struggle to accurately interpret, understand, and react to their environment in the setting of the pathological processes in their brain and emphasize increasing activity and simplifying the environment and activities of the individual with dementia [32•]. Deficits in information processing related to temporal/parietal dysfunction may produce limited ability for comprehension and can lead to irritability, aggression, and anxiety when an individual is distracted or overwhelmed. In FTD, the impaired ability to accurately interpret and respond to subtle emotional cues may make attention to the environment especially important [58]. Reducing noise and stimulation, lessening clutter, turning off music, or simplifying social situations can help these patients to accurately focus on a designated task or response. Removing access to problematic items (credit cards, mail) or modifying public outings to reduce the opportunity for inappropriate interactions are examples of FTD-specific environmental manipulations [52].

There are other behavioral modifications that have been studied in dementia that have potential application to FTD. A meta-analysis of activities suggested that a supportive environment with normal lighting, moderate sound, and small number of people and appropriate cueing were more likely to decrease behavioral symptoms in dementia [59]. Anecdotal reports and case studies of changing mealtime routines, including playing music, suggested positive results but have not been replicated in trials [60]. Certainly, addressing sensory needs that may not be able to be verbally communicated—hearing, vision, warmth, satiety, and comfort—is encouraged to avoid the expression of an unmet need through a behavioral symptom. Implementation of hearing aids in a community dwelling cohort demonstrated improved behavioral symptoms in all enrolled participants [61]. Research has identified evidence suggesting music therapy may be beneficial in managing and treating behavioral symptoms perhaps meeting an unmet need for stimulation although most research has been done in facility settings [62, 63].

Modification of activities to accommodate functional changes has been suggested to reduce agitation by reducing activation of the PLST [64]. The Tailored Activities Program (TAP) identified strengths and deficits and recommended adjustments in the physical environment to accommodate these, resulting in a significant reduction in agitation [65–67]. Case reports identify success in FTD using this approach as well [68]. Introducing old hobbies and games was successful in reducing disinhibition and inappropriate behaviors in FTD [69]. An apathy trial showed structured occupational therapy activities were more effective than “free time” in mixed group of AD, DLB, and vascular dementia patients, and music was felt to be most helpful [70]. A small but significant improvement in behavioral symptoms has been reported in a meta-analysis of occupational therapy trials using sensory stimulation [71].

Exercise has been suggested to reduce behavioral symptoms [72, 73] although a recent Cochrane review of 17 trials found no evidence of benefit of exercise on neuropsychiatric symptoms [74]. Increased daytime walking coupled with exposure to bright light did result in fewer nighttime awakenings and less time awake in the NITE-AD study [75]; however, a recent review found insufficient evidence to recommend the use of light therapy for sleep or behavioral symptoms in dementia [76]. Aberrant motor behavior may respond to physical activity, and anecdotal reports have found that environments that encourage safe wandering and ambulation may reduce attempts to exit but evidence is inconsistent [63].

Strategies for psychotic symptoms are not well studied. Confronting delusions or hallucinations using logic often results in more agitation; reassurance and distraction can be more successful. Environmental modifications such as removing mirrors or increasing lighting that may reduce the propensity for misinterpretation may be effective according to the anecdotal reports [63].

Caregiver Approaches

In the caregiver literature, there is strong evidence for the benefits of using non-pharmacological strategies. The promotion of more effective communication and pursuing ways to appropriately match the activity and environmental demands to patient abilities through education, support, and coaching has shown effectiveness in minimizing the negative outcomes associated with behavioral symptoms [29••, 77, 78]. Courses on home safety, problem solving, stress reduction, and health promotion lessened the impact of behavioral symptoms while protecting caregiver health in the NIH Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health (REACH) program [79]. Coaching via phone calls regarding caregiver stress and finding ways to create a better match between the person with dementia and their environment helped caregivers cope with behaviors [80]. Among FTD caregivers, the provision of disease education and access to support groups was reported to facilitate acceptance of the disease and an exchange of problem-solving strategies [81].

In one study, a specialty clinic focused on providing objective data relating to patient’s cognitive and functional abilities to the caregiver [82]. A reduction in behavioral symptoms and improved caregiver outcomes resulted from caregiver training using the ABC strategy for behavior management [51, 80]. Programs such as the SAVVY Caregiver have shown similar results in promoting caregiver mastery regarding behavior management and reduced caregiver stress [83–85]. The Savvy Caregiver has been adopted by some organizations for ongoing education including some chapters of the Alzheimer’s Association, allowing easy replication and transfer of proven strategies.

Behavioral Approaches

The literature on behavioral modification in FTD is sparse and consists mostly of case studies and anecdotal reports [86••]. Clinicians have focused on lack of motivation or apathy, and compulsive behaviors, when targeting challenging behaviors. Interventions for these behaviors have included using dietary or monetary rewards for desired behaviors such as showering or grooming. The use of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has been mentioned as a potential strategy for dealing with mood and behavior issues in dementia [26, 87]. In one RCT for anxiety in dementia, CBT was found to be feasible but there was no measureable impact on anxiety [88]. More investigation of this type of therapy is needed, including feasibility and efficacy in different types and severities of dementia.

Substitutions for compulsive activities, especially when out in public, might consist of offering a squeeze ball to hold, instead of touching strangers, or offering a lollipop to diminish repetitive and compulsive vocalizations [89, 90]. One case study reports the effectiveness in treating uncontrollable sexual behavior by substituting a large stuffed Pink Panther for the patient to touch and fondle [91]. These types of interventions require careful observation, and creative and individualized approaches are encouraged [90].

Conclusion

Behavioral symptoms are significant and can be disruptive to the patient, caregiver, and family. Non-pharmacological approaches to managing these symptoms with randomized, controlled trials are inconclusive; however, there is increasing evidence that these strategies when targeted and individualized with caregiver education and support exceed the benefits of pharmacological interventions and have very limited adverse effects [29••, 92]. Despite the success reported with these individualized treatments, reviews continue to provide only weak evidence for recommending these interventions on a consistent basis [63, 90].

Significant limitations around study design are evident, and only mild efficacy is suggested in the literature. Although there are behavioral profiles that represent different etiologies, it is possible that the unique individual reason for the behavior may limit measurement by traditional approaches. It may not be possible to study large numbers of patients with the same behavior who respond to the same intervention because the trigger or cause may be different. It is also possible that we are measuring the wrong outcome when we look at reduction of behavioral symptoms. It may be that accommodating the behavior in a safe environment while supporting the caregiver to reduce distress is more important than actually extinguishing the behavior. The literature is particularly robust around the efficacy of education and support on caregiver outcomes and may more accurately reflect the goal of management [32•].

It has been suggested that the non-pharmacological management of these symptoms will require multiple approaches that are individualized in the home with adequate follow-up regarding outcomes [29••]. The development of these strategies requires expertise and time, something that primary care providers do not always have. Educating providers about an approach to assessment and then identifying community resources and experts to assist in managing these symptoms will be essential, especially in syndromes such as FTD [58]. Occupational therapists have been successful developing individualized regimens incorporating environmental and behavioral strategies [66, 93]. The role of creative thinking in developing individualized approaches cannot be minimized, and publication of these anecdotal reports and case studies should be encouraged [89, 91]. These represent thoughtful interventions targeted to specific individuals but may inform others managing similar challenging behaviors. Recognition of this expertise, providing opportunities for training for professionals and non-professionals along with attempts to provide adequate reimbursement for these services may increase their availability and accessibility.

Very little attention in studies of NPS has been paid to pathologically confirmed dementia syndromes. It may be that different strategies work for different pathologies and this may be important in designing interventions and measuring efficacy. In FTD, the significant behavioral changes are particularly isolating and contribute to significant disability in both the patient and family, and yet, there are only non-systematic trials of non-pharmacological interventions in this population [86••]. The cognitive profile requires different strategies from the traditional interventions that are effective with amnestic patients. Even with promising disease modifying trials underway, the number of patients who develop dementia and suffer from these symptoms will be significant. It is imperative that we identify and communicate effective, individualized strategies to manage these debilitating symptoms according to the cognitive and behavioral profile of their disease.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently have been highlighted as • Of importance •• Of major importance

Prince M, Bryce R, Albanese E, Wimo A, Ribeiro W, Ferri CP. The global prevalence of dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(1):63,75. e2.

Waldo ML. The frontotemporal dementias. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2015;38(2):193–209.

Seltman RE, Matthews BR. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: epidemiology, pathology, diagnosis and management. CNS Drugs. 2012;26(10):841–70.

Srikanth S, Nagaraja AV, Ratnavalli E. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia-frequency, relationship to dementia severity and comparison in Alzheimer’s disease, vascular dementia and frontotemporal dementia. J Neurol Sci. 2005;236(1–2):43–8.

Lyketsos CG, Lopez O, Jones B, Fitzpatrick AL, Breitner J, DeKosky S. Prevalence of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: results from the cardiovascular health study. JAMA. 2002;288(12):1475–83.

Lyketsos CG, Steinberg M, Tschanz JT, Norton MC, Steffens DC, Breitner JC. Mental and behavioral disturbances in dementia: findings from the Cache County Study on Memory in Aging. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):708–14.

Miller BL, Darby A, Benson DF, Cummings JL, Miller MH. Aggressive, socially disruptive and antisocial behaviour associated with fronto-temporal dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:150–4.

Shinagawa S, Ikeda M, Fukuhara R, Tanabe H. Initial symptoms in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia compared with Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;21(2):74–80.

Bathgate D, Snowden JS, Varma A, Blackshaw A, Neary D. Behaviour in frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001;103(6):367–78.

Sadak TI, Katon J, Beck C, Cochrane BB, Borson S. Key neuropsychiatric symptoms in common dementias: prevalence and implications for caregivers, clinicians, and health systems. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2014;7(1):44–52.

Simard M, van Reekum R, Cohen T. A review of the cognitive and behavioral symptoms in dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(4):425–50.

Thompson C, Brodaty H, Trollor J, Sachdev P. Behavioral and psychological symptoms associated with dementia subtype and severity. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(2):300–5.

Allegri RF, Sarasola D, Serrano CM, Taragano FE, Arizaga RL, Butman J, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms as a predictor of caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2006;2(1):105–10.

Matsumoto N, Ikeda M, Fukuhara R, Shinagawa S, Ishikawa T, Mori T, et al. Caregiver burden associated with behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in elderly people in the local community. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2007;23(4):219–24.

Okura T, Plassman BL, Steffens DC, Llewellyn DJ, Potter GG, Langa KM. Neuropsychiatric symptoms and the risk of institutionalization and death: the aging, demographics, and memory study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(3):473–81.

Yaffe K, Fox P, Newcomer R, Sands L, Lindquist K, Dane K, et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002;287(16):2090–7.

Gilley DW, Bienias JL, Wilson RS, Bennett DA, Beck TL, Evans DA. Influence of behavioral symptoms on rates of institutionalization for persons with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychol Med. 2004;34(6):1129–35.

World Alzheimer Report 2012: Overcoming the stigma of dementia [Internet].; 2012 []. Available from: http://www.alz.org/documents_custom/world_report_2012_final.pdf.

Beeri MS, Werner P, Davidson M, Noy S. The cost of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD) in community dwelling Alzheimer’s disease patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2002;17(5):403–8.

de Vugt ME, Riedijk SR, Aalten P, Tibben A, van Swieten JC, Verhey FR. Impact of behavioural problems on spousal caregivers: a comparison between Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(1):35–41.

Ricci M, Guidoni SV, Sepe-Monti M, Bomboi G, Antonini G, Blundo C, et al. Clinical findings, functional abilities and caregiver distress in the early stage of dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2009;49(2):e101–4.

Massimo L, Evans LK, Benner P. Caring for loved ones with frontotemporal degeneration: the lived experiences of spouses. Geriatr Nurs. 2013;34(4):302–6.

Ma H, Huang Y, Cong Z, Wang Y, Jiang W, Gao S, et al. The efficacy and safety of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of dementia: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Alzheimers Dis. 2014;42(3):915–37.

Schneider LS, Dagerman KS, Insel P. Risk of death with atypical antipsychotic drug treatment for dementia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. JAMA. 2005;294(15):1934–43.

Schneider LS, Tariot PN, Dagerman KS, Davis SM, Hsiao JK, Ismail MS, et al. Effectiveness of atypical antipsychotic drugs in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1525–38.

Sadowsky CH, Galvin JE. Guidelines for the management of cognitive and behavioral problems in dementia. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(3):350–66.

Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG, Detroit Expert Panel on Assessment and Management of Neuropsychiatric Symptoms of Dementia. Management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in clinical settings: recommendations from a multidisciplinary expert panel. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):762–9.

Ayalon L, Gum AM, Feliciano L, Arean PA. Effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions for the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with dementia: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(20):2182–8.

Brodaty H, Arasaratnam C. Meta-analysis of nonpharmacological interventions for neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(9):946–53. Brodaty et al. reviewed 23 studies between 1985 and 2010 of trials and discuss the limitations and strengths. They propose a similar efficacy to pharmacological management in these studies.

Rosen HJ, Allison SC, Schauer GF, Gorno-Tempini ML, Weiner MW, Miller BL. Neuroanatomical correlates of behavioural disorders in dementia. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 11):2612–25.

Garcia-Alloza M, Gil-Bea FJ, Diez-Ariza M, Chen CP, Francis PT, Lasheras B, et al. Cholinergic-serotonergic imbalance contributes to cognitive and behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychologia. 2005;43(3):442–9.

Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. Assessment and management of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. BMJ. 2015;350:h369. Kales et al. reviewed manuscripts between 1992 and 2014 and present a thorough review of pharmacological and nonpharmacological management as well as a logical framework for providers to approach assessment of these symptoms.

Sparks DL, Markesbery WR. Altered serotonergic and cholinergic synaptic markers in Pick’s disease. Arch Neurol. 1991;48(8):796–9.

Geda YE, Schneider LS, Gitlin LN, Miller DS, Smith GS, Bell J, et al. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: past progress and anticipation of the future. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(5):602–8.

Sha SJ, Takada LT, Rankin KP, Yokoyama JS, Rutherford NJ, Fong JC, et al. Frontotemporal dementia due to C9ORF72 mutations: clinical and imaging features. Neurology. 2012;79(10):1002–11.

Lanata SC, Miller BL. The behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) syndrome in psychiatry. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015. Lanata and Miller review the overlap between the clinical symptoms of FTD and several primary psychiatric disorders by reviewing cases originally diagnosed with psychiatric disorders. They also discuss the current genetic implications.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Billig N. Agitated behaviors in the elderly. I. A conceptual review. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34(10):711–21.

Cohen-Mansfield J, Werner P, Marx MS. An observational study of agitation in agitated nursing home residents. Int Psychogeriatr. 1989;1(2):153–65.

Hall GR, Buckwalter KC. Progressively lowered stress threshold: a conceptual model for care of adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1987;1(6):399–406.

Richards KC, Beck CK. Progressively lowered stress threshold model: understanding behavioral symptoms of dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(10):1774–5.

Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, Rosenberg-Thompson S, Carusi DA, Gornbein J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44(12):2308–14.

de Medeiros K, Robert P, Gauthier S, Stella F, Politis A, Leoutsakos J, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory-Clinician rating scale (NPI-C): reliability and validity of a revised assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia. Int Psychogeriatr. 2010;22(6):984–94.

Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Ketchel P, Smith V, MacMillan A, Shelley T, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinical form of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233–9.

Wood S, Cummings JL, Hsu MA, Barclay T, Wheatley MV, Yarema KT, et al. The use of the neuropsychiatric inventory in nursing home residents. characterization and measurement. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2000;8(1):75–83.

Reisberg B, Borenstein J, Salob SP, Ferris SH, Franssen E, Georgotas A. Behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer’s disease: phenomenology and treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(Suppl):9–15.

Reisberg B, Monteiro I, Torossian C, Auer S, Shulman MB, Ghimire S, et al. The BEHAVE-AD assessment system: a perspective, a commentary on new findings, and a historical review. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2014;38(1–2):89–146.

Knopman DS, Kramer JH, Boeve BF, Caselli RJ, Graff-Radford NR, Mendez MF, et al. Development of methodology for conducting clinical trials in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 11):2957–68.

Mioshi E, Hsieh S, Savage S, Hornberger M, Hodges JR. Clinical staging and disease progression in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2010;74(20):1591–7.

Gitlin LN, Marx KA, Stanley IH, Hansen BR, Van Haitsma KS. Assessing neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with dementia: a systematic review of measures. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(11):1805–48.

Smith M, Buckwalter K. Back to the A-B-C’s: understanding and responding to behavioral symptoms in dementia. Geriatr Mental Health Train Ser,. Rev 2005.

Teri L, McCurry SM, Logsdon R, Gibbons LE. Training community consultants to help family members improve dementia care: a randomized controlled trial. Gerontologist. 2005;45(6):802–11.

Merrilees J. A model for management of behavioral symptoms in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2007;21(4):S64–9.

Hodgson NA, Gitlin LN, Winter L, Czekanski K. Undiagnosed illness and neuropsychiatric behaviors in community residing older adults with dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25(2):109–15.

Segal-Gidan F, Cherry D, Jones R, Williams B, Hewett L, Chodosh J, et al. Alzheimer’s disease management guideline: update 2008. Alzheimers Dement. 2011;7(3):e51–9.

Gitlin LN, Kales HC, Lyketsos CG. Nonpharmacologic management of behavioral symptoms in dementia. JAMA. 2012;308(19):2020–9.

Dementia: principles of care for patients with dementia resulting from alzheimer disease [Internet].; 2006 []. Available from: www.aagponlin.org/positionstatement.

APA Work Group on Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias, Rabins PV, Blacker D, Rovner BW, Rummans T, Schneider LS. American Psychiatric Association practice guideline for the treatment of patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. Second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(12 Suppl):5–56.

Kortte KB, Rogalski EJ. Behavioural interventions for enhancing life participation in behavioural variant frontotemporal dementia and primary progressive aphasia. Int Rev Psychiatr. 2013;25(2):237–45.

Trahan MA, Kuo J, Carlson MC, Gitlin LN. A systematic review of strategies to foster activity engagement in persons with dementia. Health Educ Behav. 2014;41(1 Suppl):70S–83S.

Watson R, Green SM. Feeding and dementia: a systematic literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(1):86–93.

Palmer CV, Adams SW, Bourgeois M, Durrant J, Rossi M. Reduction in caregiver-identified problem behaviors in patients with Alzheimer disease post-hearing-aid fitting. J Speech Lang Hear Res. 1999;42(2):312–28.

Raglio A, Bellelli G, Traficante D, Gianotti M, Ubezio MC, Villani D, et al. Efficacy of music therapy in the treatment of behavioral and psychiatric symptoms of dementia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2008;22(2):158–62.

Livingston G, Johnston K, Katona C, Paton J, Lyketsos CG, Old Age Task Force of the World Federation of Biological Psychiatry. Systematic review of psychological approaches to the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(11):1996–2021.

Moniz Cook ED, Swift K, James I, Malouf R, De Vugt M, Verhey F. Functional analysis-based interventions for challenging behaviour in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2:CD006929.

O’Connor CM, Clemson L, Brodaty H, Jeon YH, Mioshi E, Gitlin LN. Use of the Tailored Activities Program to reduce neuropsychiatric behaviors in dementia: an Australian protocol for a randomized trial to evaluate its effectiveness. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(5):857–69.

Gitlin LN, Winter L, Burke J, Chernett N, Dennis MP, Hauck WW. Tailored activities to manage neuropsychiatric behaviors in persons with dementia and reduce caregiver burden: a randomized pilot study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2008;16(3):229–39.

Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hodgson N, Hauck WW. Targeting and managing behavioral symptoms in individuals with dementia: a randomized trial of a nonpharmacological intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(8):1465–74.

O’Connor CM, Clemson L, Brodaty H, Gitlin LN, Piguet O, Mioshi E. Enhancing caregivers’ understanding of dementia and tailoring activities in frontotemporal dementia: two case studies. Disabil Rehabil. 2015;9:1–11.

Ikeda M, Tanabe H, Horino T, Komori K, Hirao K, Yamada N, et al. Care for patients with Pick’s disease by using their preserved procedural memory. Sheishin Shinkeigaku Zasshi. 1995;97:179.

Ferrero-Arias J, Goni-Imizcoz M, Gonzalez-Bernal J, Lara-Ortega F, da Silva-Gonzalez A, Diez-Lopez M. The efficacy of nonpharmacological treatment for dementia-related apathy. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2011;25(3):213–9.

Kim SY, Yoo EY, Jung MY, Park SH, Park JH. A systematic review of the effects of occupational therapy for persons with dementia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. NeuroRehabilitation. 2012;31(2):107–15.

Hulme C, Wright J, Crocker T, Oluboyede Y, House A. Non-pharmacological approaches for dementia that informal carers might try or access: a systematic review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2010;25(7):756–63.

Teri L, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, Logsdon RG, Buchner DM, Barlow WE, et al. Exercise plus behavioral management in patients with Alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290(15):2015–22.

Forbes D, Forbes SC, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, Forbes S. Exercise programs for people with dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;4:CD006489.

McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Logsdon RG, Vitiello MV, Teri L. Nighttime insomnia treatment and education for Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53(5):793–802.

Forbes D, Blake CM, Thiessen EJ, Peacock S, Hawranik P. Light therapy for improving cognition, activities of daily living, sleep, challenging behaviour, and psychiatric disturbances in dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD003946.

Kales HC, Gitlin LN, Lyketsos CG. The time is now to address behavioral symptoms of dementia. Generations - J Am Soc Aging. 2014;38(86–95).

Parker D, Mills S, Abbey J. Effectiveness of interventions that assist caregivers to support people with dementia living in the community: a systematic review. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2008;6(2):137–72.

Gitlin LN, Winter L, Corcoran M, Dennis MP, Schinfeld S, Hauck WW. Effects of the home environmental skill-building program on the caregiver-care recipient dyad: 6-month outcomes from the Philadelphia REACH Initiative. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):532–46.

Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Hodgson N, Hauck WW. A biobehavioral home-based intervention and the well-being of patients with dementia and their caregivers: the COPE randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(9):983–91.

Diehl J, Mayer T, Kurz A, Forstl H. Features of frontotemporal dementia from the perspective of a special family support group. Nervenarzt. 2003;74(5):445–9.

Barton C, Merrilees J, Ketelle R, Wilkins S, Miller B. Implementation of advanced practice nurse clinic for management of behavioral symptoms in dementia: a dyadic intervention (innovative practice). Dementia (London). 2014;13(5):686–96.

Samia LW, Aboueissa AM, Halloran J, Hepburn K. The Maine Savvy Caregiver Project: translating an evidence-based dementia family caregiver program within the RE-AIM Framework. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57(6–7):640–61.

Kally Z, Cote SD, Gonzalez J, Villarruel M, Cherry DL, Howland S, et al. The Savvy Caregiver Program: impact of an evidence-based intervention on the well-being of ethnically diverse caregivers. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2014;57(6–7):681–93.

Hepburn K, Lewis M, Tornatore J, Sherman CW, Bremer KL. The Savvy Caregiver program: the demonstrated effectiveness of a transportable dementia caregiver psychoeducation program. J Gerontol Nurs. 2007;33(3):30–6.

Hinagawa S, Nakajima S, Plitman E, Graff-Guerrero A, Mimura M, Nakayama K, et al. Non-pharmacological management for patients with frontotemporal dementia: a systematic review. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45(1):283–93. Shinagawa et al. reviewed the literature for evidence of efficacy of nonpharmacological strategies in managing the challenging behaviors in FTD. They found no randomized controlled trials and make recommendations for future research.

Buchanan JA, Christenson A, Houlihan D, Ostrom C. The role of behavior analysis in the rehabilitation of persons with dementia. Behav Ther. 2011;42(1):9–21.

Spector A, Charlesworth G, King M, Lattimer M, Sadek S, Marston L, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for anxiety in dementia: pilot randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2015;206(6):509–16.

Fick WF, van der Borgh JP, Jansen S, Koopmans RT. The effect of a lollipop on vocally disruptive behavior in a patient with frontotemporal dementia: a case-study. Int Psychogeriatr. 2014;26(12):2023–6.

Lavretsky H. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer disease and related disorders: why do treatments work in clinical practice but not in the randomized trials? Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2008;16(7):523–7.

Tune LE, Rosenberg J. Nonpharmacological treatment of inappropriate sexual behavior in dementia: the case of the pink panther. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2008;16(7):612–3.

Covinsky KE, Johnston CB. Envisioning better approaches for dementia care. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(10):780–1.

Fraker J, Kales HC, Blazek M, Kavanagh J, Gitlin LN. The role of the occupational therapist in the management of neuropsychiatric symptoms of dementia in clinical settings. Occup Ther Health Care. 2014;28(1):4–20.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Cynthia Barton, Robin Ketelle, and Jennifer Merrilees each declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Bruce Miller receives grant support from the NIH/NIA and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) as grants for the Memory and Aging Center. As an additional disclosure, Dr. Miller serves as Medical Director for the John Douglas French Foundation; Scientific Director for the Tau Consortium; Director/Medical Advisory Board of the Larry L. Hillblom Foundation; and Scientific Advisory Board Member for the National Institute for Health Research Cambridge Biomedical Research Centre and its subunit, the Biomedical Research Unit in Dementia (UK).

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Behavior

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Barton, C., Ketelle, R., Merrilees, J. et al. Non-pharmacological Management of Behavioral Symptoms in Frontotemporal and Other Dementias. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep 16, 14 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-015-0618-1

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11910-015-0618-1