Abstract

Background

The purpose of this paper was to search for predictive factors for proximal leakage after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) in a large cohort from a single referral center.

Materials and Methods

One thousand seven hundred and thirty-eight patients, collected in a prospectively held database from 2008 to 2016, were retrospectively analyzed. The correlation between postoperative leakage and both preoperative (age, gender, height, weight, BMI, and obesity-related morbidities) and operative variables (the distance from pylorus at which the gastric section was started, operative time, experience of surgeons who performed the LSG, and the surgical materials used) was analyzed. The experience of the surgeons was calculated in the number of LSGs performed. The surgical materials considered were stapler, cartridges, and reinforcement of the suture.

Results

Proximal leakage was observed in 45 patients out of 1738 (2.6%). No correlation was found between leakage and the preoperative variables analyzed. The operative variables that were found to be associated with lower incidence of leakage at the multivariate analysis (p < 0.05) were the reinforcement of the staple line (or overriding suture or buttressing materials) and the experience of the surgeons. A distance of less than 2 cm from the pylorus resulted to be significantly related to a higher incidence of fistula at the univariate analysis.

Conclusions

In this large consecutive cohort study of LSG, proximal staple line reinforcement (buttress material or suture) reduced the risk of a leak. The risk of a proximal leak was much higher in the surgeons first 100 cases, which has implications for training and supervision during this “learning curve” period.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Bariatric surgery is now widely accepted as the only long standing, effective therapy for morbid obesity. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) is one of the most performed surgical procedure in bariatric surgery [1,2,3,4,5]. An increasing number of large mono-centric studies and reviews are reporting good overall outcomes regarding the safety of the procedure, its medium-term results, and the positive impact on obesity-related morbidities [6,7,8,9,10].

Leakage is currently considered the main complication affecting LSG, with reported rates ranging between 0 and 8% [4, 11,12,13,14]. The localization is at the proximal third of the staple line in 89.9% of patients [12]. This constitutes the second cause of death after bariatric surgery with an overall mortality rate ranging from 0 to 1.4% [15].

The analysis from Aurora et al. [16] highlighted an increased risk in patients with a BMI > 50 kg/m2 and the use of a boogie size < 40-Fr during the procedure. A detailed analysis of 11,800 LSGs from the German Bariatric Surgery National Registry reported a significant decrease of staple line leak rate with a 10-minute longer operation time, the use of both suture and buttresses for staple line reinforcement, the avoidance of intra-operative leakage testing, and a lower median age of the patients [17].

One of the most reliable hypothesis for leakage development, proposed by Baker et al., identifies two groups of causes, related to mechanical and ischemic aspects [18, 19]. The mechanical factors are linked to the intrinsic characteristics of the long staple line of LSG and the thickness of the gastric wall. The correct choice of cartridge for stapling is very important.

Instead, the ischemic aspects are related to the most common location of the leakage, which is at the esophagogastric (EG) junction. Saber et al. [20] focused on the gastric wall perfusion based on CT scan evaluation. The authors demonstrated that gastric wall perfusion is significantly decreased at the angle of His and at the gastric fundus, as opposed to other gastric areas. This was particularly evident for obese patients in comparison to non-obese patients and was statistically significant only at the fundus. Ninety-six percent of the panel experts at the International Consensus Summit for Sleeve Gastrectomy “believed that it is important to stay away from the EG junction on the last firing” [21].

The main aim of this study is the search for a predictive factor for leakage following LSG in a large cohort from a single referral center.

Materials and Methods

This study is a retrospective analysis of a cohort of obese patients who underwent laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) from January 2008 to October 2016 [22]. The database was prospectively held and includes obese patients enrolled for LSG at San Giuseppe Hospital, Milan (2008–2010), and at San Marco Hospital, Zingonia, Bergamo (2010–2016). All patients were operated on by the same group of surgeons. Demographics, anthropometrics, comorbidities, perioperative, operative, and postoperative data were collected. Body mass index (BMI) was used to define the grade of obesity and its variations. Patients enrolled for LSG had a preoperative BMI > 40 kg/m2 or between 30 and 40 kg/m2 with obesity-related comorbidities. The preoperative workup included a multidisciplinary evaluation from a dedicated psychologist, dietitian, endocrinologist, and anesthesiologist. All patients signed an informed consent. Patients who underwent LSG after a previous different bariatric intervention were excluded from the analysis. Patients who underwent LSG in combination with another general surgery procedure were included.

The primary end point of this study was the leakage rate following LSG. Leakage was defined as “an effluence of gastrointestinal contents through a suture line, which may collect near an anastomosis, or exit through the wall or the drain” [18]. Potential predictive preoperative and operative variables included in the study are shown respectively in Tables 1 and 2. The experience of the surgeons was considered as an operative variable, and it was calculated based on the number of LSGs performed, including those performed during the training years.

Intervention

LSG was performed using four trocars. Pneumoperitoneum was induced through a Veress needle placed in the left sub-costal space. A 10-mm trocar was placed in the left sub-costal space for the optic. The other trocars were placed under vision: a 5-mm trocar in the epigastrium, a 5-mm trocar in the right hypochondrium along the great gastric curvature in correspondence with the pylorus, and a 15-mm trocar in the mesogastrium along the great gastric curvature, slightly to the left of the midline, in line with the esophageal hiatus. A laparoscopic retractor for the liver was used to expose the surgical field. The great curvature was dissected and isolated from the gastrocolic ligament and the splenocolic ligament through an ultrasonic device (Harmonic ACE®, Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, Ohio) or a radiofrequency sealer device (LigaSure Maryland™ Jaw, Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland; or ConMed Altrus®, ConMed Electrosurgery, Centennial, CO, USA) or an integrated device of both advanced bipolar energy and ultrasonic energy (Thunderbeat®, Olympus Medical System Corp., Tokyo, Japan). The distance from the pylorus was measured by the laparoscopic grasper calculating the distance between the tips of the grasper as 2 cm when opened. The dissection was conducted up to the angle of His, freeing the fundus and the left pillar. If a hiatal hernia was present, it was reduced, and if necessary, a hiatoplasty was performed. A 38 Fr oro-gastric boogie was inserted, and the section was done staying a few millimeters away from the boogie, to avoid tissue stretching and the incomplete closure of the stapler. The linear stapler used were Covidien Endo GIA™ 60 Reloads with or without Tri-staple™ Technology (Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland) and Ethicon Echelon Flex™ 60 Endopath Stapler (Ethicon Endo-Surgery Inc., Cincinnati, OH). The choice of a particular cartridge depended on the tissue thickness according to the intra-operative perception and experience of the surgeon. We know from anatomical studies that gastric thickness decreases from the bottom to the top and from the medial to the lateral position [23, 24]. In most of the LSGs, the highest part of the suture was reinforced with an overriding suture: PDS 3/0 (MIC55E, PDS II, Ethicon Endo-Clip Suture, Cincinnati, OH, USA) or Polysorb 2/0 (Endostitch™ Suturing Device, Covidien, Dublin, Ireland), or with buttress material: bovine pericardium (Peri-strip® Dry, Synovis Life Technologies, Inc., St. Paul, MN, USA) or polyglycolic acid (Endo GIA™ Reinforced Reloaded with Tri-Staple™ Technology, Medtronic, Dublin, Ireland). At the end of the section, the oro-gastric boogie was extracted and a drainage was placed along the new gastric tubule. At the beginning of the experience, we used to perform an hydro-pneumatic test with methylene blue to intra-operatively check the presence of a leakage. We also used to place a nasogastric tube for the first two postoperative days.

Postoperative Course

On the first postoperative day, the patient was mobilized and the urinary catheter was removed. On the second day, the patient underwent upper GI series with water-soluble contrast by mouth (Gastrografin 370 mg iodine/ml gastroenteric solution, Bayer SPA). If the series showed a regular transit and no signs of leakage, the patient started a liquid diet on the same day. Blood tests were performed on the first and third postoperative days. In the case of a regular course, the patient was discharged in the fourth postoperative day with a liquid diet.

Statistics

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize patient characteristics. This included mean and standard deviation, minimum, maximum, and median with the inter-quartile range (IQR) for continuous variables and counts and percentages for categorical variables. Summary statistics were reported with a maximum of two decimals.

The software SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used to perform statistical analyses. Statistical tests were based on a two-sided significance level of 0.05.

The analysis regarding the main aim was performed using the logistic regression model. Bivariate odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were estimated for each potential predictor present in the database. The multivariate logistic regression model was performed using both the stepwise selection procedure considering all the variables collected in the database and the selection based on the significant association (p ≤ 0.05) identified from the bivariate logistic analysis. In order to avoid an over-fitted and unstable model, the correlation coefficient between the variables should be less than 0.20. For the multivariate models, the presence of the event will be the dependent variable.

Results

Demographics and Operative Findings

A total of 1738 patients who underwent LSG were analyzed. The baseline and demographic characteristics are summarized in Table 1. One thousand six hundred and eighty-two (96.8%) patients underwent LSG alone. Fifty-six patients underwent LSG plus additional procedures: four had resection of gastric tumors (GIST), one had a removal of a benign omental nodule, 16 patients had a resection of benign hepatic nodules, one had an umbilical hernioalloplasty, one had a genital frenectomy, 23 had a hiatoplasty, one had a removal of an intragastric balloon, and nine had a cholecystectomy. The majority of the patients were operated by expert surgeons. In the past 8 years, 14 surgeons have been involved in our bariatric team. The operative findings and the materials used are summarized in Table 2. The choice of the cartridges was Green for Echelon and Black for Tri-Staple at the antrum and Gold for Echelon and Purple for Tri-Staple at the mid-body. We noticed a big variability regarding the choice of the cartridge for the fundus, as reported in Table 2. A mean number of six cartridges was used for each procedure.

Leakage Rate and Presentation:

Leakage was observed in 48 patients out of 1738 (2.8%). In three patients, the leakage appeared at the bottom of the gastric suture (0.2%), and it was related to a mechanical problem during the gastric section. In all three cases, the leakage was evident at the routine upper GI series on the second postoperative day, and it was easily managed by a laparoscopic intervention with suture of the gastric dehiscence. In 45 patients, the leakage appeared at the proximal part of the gastric suture (2.6%). Seven patients were diagnosed by routine postoperative upper GI series, with evidence of proximal leakage (15.6%). Eighty-four percent of the patients developed leakage later, with a mean time of onset after surgery of 18.7 ± 10.7 days. These patients had a negative upper GI series on day two; they started a liquid diet and were discharged without clinical or laboratory signs of leakage. In the majority of patients, the diagnosis was made within 3 weeks after surgery (88.9%). In three patients, the leakage appeared between the third and sixth weeks (6.7%), and in two patients, it appeared between the seventh and ninth weeks after surgery (4.4%). All patients who developed a proximal leakage came back to our department with abdominal pain and fever. They underwent blood tests showing leukocytosis and had a CT scan with gastrografin per os showing leakage. In 42 cases (93.3%), the leakage was associated with an abdominal abscess (between 1 and 6 cm), and in 24 cases (53%), there was evidence of free intra-abdominal air.

Risk Factors for Leakage

Baseline and operative variables collected in our LSG database, summarized in Tables 1 and 2, were analyzed in correlation with the proximal leakage rate in a univariate logistic regression. The results are summarized in Table 3. There was no difference in the development of a leakage between LSG alone and LSG plus additional procedure, even when the additional procedure was hiatoplasty.

A higher rate of leakage was associated with a gastric resection started at a distance less than 2 cm from the pylorus, 5.5% (p = 0.026, OR = 2.44, 95% CI 1.11–5.33), and with the use of stapler cartridges without reinforcement in the section of the gastric fundus, 4.9% (p = 0.040, OR = 2.18, 95% CI 1.03–4.61).

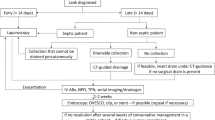

Two factors resulted to be protective against leakage: the experience of the surgeon and the use of reinforcement over the proximal third of the staple line. An increase of the number of LSGs performed by the surgeon seems to be related to a decrease of the leakage rate (Fig. 1). We noticed that those two surgeons who had performed a larger number of LSGs in the study (1015 out of a total of 1738; 58.4%) had a mean rate of leakage of 1.8%, with a risk of leakage significantly lower than the other surgeons (p = 0.013, OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.25–0.85). There was evidence of a lower rate of leakage with the use of reinforcement in the proximal part of the gastric suture, 2.3% (p = 0.040, OR = 0.46, 95% CI 0.22–0.97), regardless of the types of reinforcement. With buttressing material, we had a lower rate of leakage than with overriding suture (1.8 and 2.4%, respectively), but this was not significant (p = 0.438 and 0.365, respectively).

The analysis did not show other differences in terms of materials used (staplers and cartridges) related to the rate of leakage. Methylene blue test and nasogastric tube placement were not related to a better outcome in terms of leakage development (Table 3).

A stepwise multivariable analysis was performed to look for independent predictors of leakage. Two different models are represented in Table 4 according to the variables included in the analysis. In the first model, all the variables collected in the database were included. The reinforcement of the suture over the proximal part of the stomach resulted to be the only independent protective factor against leakage in this first model (p = 0.002, OR = 0.29, 95% CI 0.13–0.64).

In the second model, we considered only the variables whose results were significant at the univariate analysis (p < 0.05): the use of reinforcement materials (p < 0.001, OR = 0.19, 95% CI 0.09–0.45) and the surgeon’s experience (p = 0.036, OR = 0.49, 95% CI 0.25–0.95), both resulted as independent protective factors against leakage development.

A distance from the pylorus of less than 2 cm did not result in correlation with the development of leakage (p = 0.054, OR = 0.82, 95% CI 0.66–1.01), despite the correlation at the univariate analysis.

Conclusion

The reported rate of leakage in the cohort analyzed was 2.8%: 2.6% in the proximal part of the gastric suture and 0.2% in the lower part. In the literature, the rate of leakage after LSG is described to be between 0 and 8% [4, 11,12,13,14]. The leakage at the lower part of the stomach is mainly related to technical problems. Issues can derive from the choice of an incorrect length of the cartridges for a thick tissue or from inappropriate traction during the section of the stomach. The real concerns of the surgeons are related to proximal leakage because of its difficult management and resolution, with greater discomfort for the patient compared to a lower leakage. In this study, we focused on the correlations between the proximal leakage rate and any of the variables collected in our prospectively held database.

No correlation was noted between leakage and the preoperative variables analyzed (age, sex, BMI, comorbidities). This finding does not confirm the evidence about BMI from the systematic analysis of the literature done by Aurora et al. [16], in which a higher incidence of leakage in super obese patients (BMI > 50 kg/m2) was described. The heavier the patient, the more difficult the intervention and the higher is the risk of leakage. Despite this assumption, we report that a higher BMI is not significantly correlated with an increased incidence of leakage. In our experience, the rate of leakage decreased considering higher BMI: in the 50–59 kg/m2 BMI class, we had a 1.3% rate, and in the class of BMI > 60 kg/m2, we had 1.9% compared to the 2.6% rate in the total population (Table 3).

As described by other authors [17, 25], we found that in the obese male population, the rate of leakage was higher (3.0%) than in females (2.4%), but without statistical significance.

The first independent variable that resulted to be related to a lower incidence of leakage was the reinforcement of the staple line (Table 4), with a p = 0.002 (OR = 0.289, 95% CI 0.130–0.642) at the stepwise model 1 and with a p < 0.001 (OR = 0.198, 95% CI 0.086–0.453) at the stepwise model 2. Many authors posed the question of the utility of reinforcing the staple line with an overriding suture or buttressing materials. From our data, we can say that the use of reinforcement over the proximal part of the staple line is correlated to a reduced rate of leakage. The leakage rate decreased from 4.9% in staple line without reinforcement to 2.3% in patients with staple line reinforcement. We did not find a significant difference between over-sewing the staple line and using buttressing materials, although when treated with buttressing materials, patients had a lower rate of leakage (Table 3). In the literature, this finding is still the object of debate. Some authors show that reinforcement may decrease the incidence of leakage, others that it has no impact or that it can even increase the incidence of leakage [11, 16, 17]. Most of the authors suggest attention in the evaluation of the thickness of the gastric wall in order to select the right cartridges for the stapling [18, 19, 23, 24]. The choice of the wrong cartridge can lead to the formation of an area of weakness along the staple line. The thickness of the buttressing material over an inadequate cartridge may lead to a higher risk of leakage. In the same way, over-sewing a previously ischemic staple line, due the choice of the wrong cartridge related to the thickness of the gastric wall, can increase the weakness of the tissue. For this reason, the choice of the right cartridges for the right part of the stomach is critical.

The growing experience of the surgeons resulted to be the second most related variable to a lower incidence of leakage at the stepwise model 2 (p = 0.036, OR = 0.490, 95% CI 0.252–0.953). This finding is in accordance with the large study based on the German Bariatric Surgery Registry [17], and it could be explained by the fact that experienced operators are more familiar with the international recommendation and standards of practice: to staple not too close to the oro-gastric boogie, regardless of its caliber; to give the right tension to the tissues along the staple line without stretching the vessels and creating a weak ischemic area; to stay away from the EG junction when firing the last cartridges; to choose the right material for stapling. These recommendations come from expert surgeons to avoid mechanical and ischemic issues that could be at the origin of leakage [20, 21]. Considering our data, it is difficult to indicate a precise number of LSGs that could be considered a cut off for a complete learning curve. In Fig. 1, it is shown that the curve of leakage rate continuously decrease after a personal experience of 150–200 LSGs. Even lowering that number, we found that the data became significant, in terms of reducing leakage, only for the two surgeons who performed more LSGs (58.4% of the total). The risk of a proximal leak was much higher in the surgeons’ first 100 cases, even though they were expert laparoscopic surgeons. This has implications for training and supervision during the “learning curve” period. LSG seems to be an easy intervention for expert laparoscopic surgeons, but Fig. 1 shows that it should not be underestimated. Considering our recent data, our policy is to let surgeons perform LSG during their learning curve, even if expert in laparoscopic surgery, under the supervision of an experienced surgeon in LSG.

The distance from the pylorus at which we started the gastric section was another operative variable related to the development of leakage at the univariate analysis (p = 0.026, OR = 2.44, 95% CI 1.11–5.33) but not at the multivariate models. The patients in which we started the section at a distance lower than 2 cm had an incidence of leakage of 5.5%, significantly higher than others. This finding is controversial in literature. The first report from the MBSAQIP (Metabolic and Bariatric Accreditation and Quality Improvement Program) and a meta-analysis of 9991 cases showed that the distance from the pylorus does not impact on leakage [12, 26]. However, this evidence may be interesting because it highlights an intrinsic feature of the new gastric tubule after LSG: the intraluminal pressure is higher compared to the stomach before LSG. The pylorus works as a sphincter and the pressure in this area is the highest. An area of weakness due to technical or ischemic problems when exposed to high pressures can be at risk of leakage.

Finally, as already described [17], we found a higher incidence of leakage after longer interventions even if it was not significant (Table 3). We found that for procedures that lasted longer than 90 min, the rate of leakage was 5.6% (p = 0.109, OR = 2.37, 95% CI 0.82–6.80). It is easy to think that a longer procedure is more demanding for the operator and can lead to technical errors. A higher BMI, the presence of an associated procedure (e.g., hiatoplasty and others), and the experience of the operator were not related to a longer procedure.

In conclusion, despite the limitations of a retrospective study, we feel that the data from the large series of patients analyzed allow us to suggest to reinforce the last part of the staple line with buttressing or an overriding suture, to have a complete learning curve or to work under the supervision of an expert surgeon, and to start the dissection at a distance >2 cm from the pylorus.

References

Deitel M, Crosby RD, Gagner M. The First International Consensus Summit for Sleeve Gastrectomy (SG), New York City, October 25-27, 2007. Obes Surg. 2008;18(5):487–96.

Gagner M, Deitel M, Kalberer TL, et al. The Second International Consensus Summit for Sleeve Gastrectomy, March 19-21, 2009. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2009;5(4):476–85.

Deitel M, Gagner M, Erickson AL, et al. Third International Summit: current status of sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7(6):749–59.

Gagner M, Deitel M, Erickson AL, et al. Survey on laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) at the Fourth International Consensus Summit on Sleeve Gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2013;23(12):2013–7.

Gagner M, Hutchinson C, Rosenthal R. Fifth International Consensus Conference: current status of sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(4):750–6.

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Bariatric surgery worldwide 2013. Obes Surg. 2015;25(10):1822–32.

Juodeikis Ž, Brimas G. Long-term results after sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13(4):693–9.

Gadiot RP, Biter LU, van Mil S, et al. Long-term results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity: 5 to 8-year results. Obes Surg. 2017;27(1):59–63.

Sakran N, Raziel A, Goitein O, et al. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for morbid obesity in 3003 patients: results at a high-volume bariatric center. Obes Surg. 2016;26(9):2045–50.

Wang X, Chang XS, Gao L, et al. Effectiveness of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for weight loss and obesity-associated co-morbidities: a 3-year outcome from Mainland Chinese patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12(7):1305–11.

Gagner M, Buchwald JN. Comparison of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy leak rates in four staple-line reinforcement options: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10(4):713–23.

Berger ER, Clements RH, Morton JM, et al. The impact of different surgical techniques on outcomes in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies: the first report from the metabolic and bariatric surgery accreditation and quality improvement program (MBSAQIP). Ann Surg. 2016;264(3):464–73.

Stroh C, Birk D, Flade-Kuthe R, et al. Results of sleeve gastrectomy—data from a nationwide survey on bariatric surgery in Germany. Obes Surg. 2009;19(5):632–40.

Hutter MM, Schirmer BD, Jones DB, et al. First report from the American College of Surgeons Bariatric Surgery Center Network: laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy has morbidity and effectiveness positioned between the band and the bypass. Ann Surg. 2011;254(3):410–20. discussion 420-2

Jurowich C, Thalheimer A, Seyfried F, et al. Gastric leakage after sleeve gastrectomy-clinical presentation and therapeutic options. Langenbeck's Arch Surg. 2011;396(7):981–7.

Aurora AR, Khaitan L, Saber AA. Sleeve gastrectomy and the risk of leak: a systematic analysis of 4,888 patients. Surg Endosc. 2012;26(6):1509–15.

Stroh C, Köckerling F, Volker L, et al. Results of more than 11,800 sleeve gastrectomies: data analysis of the German Bariatric Surgery Registry. Ann Surg. 2016;263(5):949–55.

Iossa A, Abdelgawad M, Watkins BM, et al. Leaks after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: overview of pathogenesis and risk factors. Langenbeck's Arch Surg. 2016;401(6):757–66.

Baker RS, Foote J, Kemmeter P, et al. The science of stapling and leaks. Obes Surg. 2004;14(10):1290–8. Review. Erratum in: Obes Surg. 2013 Dec;23(12):2124

Saber AA, Azar N, Dekal M, et al. Computed tomographic scan mapping of gastric wall perfusion and clinical implications. Am J Surg. 2015;209(6):999–1006.

Rosenthal RJ, International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel, Diaz AA, et al. International Sleeve Gastrectomy Expert Panel Consensus Statement: best practice guidelines based on experience of >12,000 cases. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2012;8(1):8–19.

Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61(4):344-9.

Elariny H, González H, Wang B. Tissue thickness of human stomach measured on excised gastric specimens from obese patients. Surg Technol Int. 2005;14:119–24.

Huang R, Gagner M. A thickness calibration device is needed to determine staple height and avoid leaks in laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2015;25(12):2360–7.

Sakran N, Goitein D, Raziel A, et al. Gastric leaks after sleeve gastrectomy: a multicenter experience with 2,834 patients. Surg Endosc. 2013;27(1):240–5.

Parikh M, Issa R, McCrillis A, et al. Surgical strategies that may decrease leak after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of 9991 cases. Ann Surg. 2013;257(2):231–7.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Ethical Approval

For this type of study formal consent is not required.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(XLS 584 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cesana, G., Cioffi, S., Giorgi, R. et al. Proximal Leakage After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy: an Analysis of Preoperative and Operative Predictors on 1738 Consecutive Procedures. OBES SURG 28, 627–635 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2907-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-017-2907-z