Abstract

Background

Surgical resection is currently indicated for all potentially resectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), but the survival outcomes and the prognostic factors have not been well-documented due to its rarity. This study aims to assess these in a large, consecutive series of patients with ICC treated surgically.

Methods

A retrospective study was conducted on 1,333 ICC patients undergoing surgery between January 2007 and December 2011. Surgical results and survival were evaluated and compared among different subgroups of patients. Univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to identify prognostic factors.

Results

R0, R1, R2 resection and exploratory laparotomy were obtained in 34.8, 44.9, 16.4, and 3.9 % of the patients, respectively. The overall 1-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates for the entire cohort were 58.2, 25.2, and 17.0 %, respectively, with corresponding rates of 79.1, 42.6, and 28.7 % for patients with R0 resection; 60.5, 20.1, and 13.9 % for patients with R1 resection; 20.5, 7.4, and 0 % for patients with R2 resection; and 3.8, 0, and 0 % for patients with an exploratory laparotomy. Independent factors for poor survival included positive resection margin, lymph node metastasis, multiple tumors, vascular invasion, and elevated CA19-9 and/or CEA, whereas hepatitis B virus infection and cirrhosis were independently favorable prognosis indicators.

Conclusions

R0 resection offers the best possibility of long-term survival, but the chance of a R0 resection is low when surgery is performed for potential resectable ICC. Further randomized trials are warranted to refine indications for surgery in the management of ICC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC), originating from small bile duct epithelium or hepatic progenitor cells within the liver,1 is the second most common primary liver cancer after hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Perhaps, under the shadows of HCC which has been extensively studied, ICC remains much less well understood.2 – 4 It is generally believed that ICC is primarily a surgical disease, and surgical resection offers the only prospect for long-term survival.5 – 8 Therefore, surgical resection is currently indicated for patients with potentially resectable ICC regardless of stage due to lack of other effective treatment options.7 , 9 – 13 However, although there have been increasing studies on ICC surgery,5 – 8 , 13 – 20 survival outcomes and the prognostic factors based on all potential resectable ICC have not been well-documented. The 5-year survival after surgical resection of ICC differed greatly among different research groups (ranging from 4.1 to 43.8 %), with a median survival time (MST) varying from 11.0 to 37.4 months,3 , 12 , 14 , 15 , 21 – 26 and many factors have been found to predict prognosis after surgical resection for ICC, but a consensus has not yet been reached with regard to the factors that could significantly and independently influence the survival.19 , 24 – 26 All of these may be due to the fact that, owing to rarity of ICC, most of the available data retrieved from studies on small series that usually spanned over a long study period of decades.

In recent years, both the incidence and mortality of ICC have risen worldwide,2 – 4 , 24 , 27 highlighting the need for more recent prognostic data from large series to define optimal surgical management of ICC. In this study, therefore, we investigated outcomes in a large cohort of patients who underwent surgery for potentially resectable ICC, with the aim of clarifying the current role of surgery in the management of ICC and the factors that have prognostic significance.

Patients and Methods

Patients and Operation

All consecutive patients with ICC who were treated surgically between January 2007 and December 2011 at our institution were retrospectively evaluated. The patients were identified through computerized hospital databases that encompassed all such cases. Demographic data were collected for each patient, including age, genders, symptoms, underlying liver diseases, image findings, laboratory tests, and pathological results.

Standard preoperative workup consisted of ultrasound scan; three-phase computed tomography (CT) and/or magnetic resonance imaging of the liver, cardiac, and pulmonary function testing; CT scan of the chest, endoscopic examination; and a range of laboratory tests. In some patients, positron emission tomography and CT was performed for further diagnostic workup and metastatic evaluation. If preoperative imaging studies indicated a potentially resectable ICC and there were no general contraindications for surgery, the patient underwent surgical exploration. At exploration, when multinodular intrahepatic tumor spread or peritoneal carcinomatosis or both were found, the patient underwent either biopsy for pathological confirmation of the diagnosis or palliative resection depending on intraoperative assessment. Otherwise, liver resections were performed with curative intention. All patients underwent a macroscopic assessment of lymph node (LN) status, and a lymphadenectomy was performed additionally in patients with suspected LN metastasis by intraoperative assessment as well as preoperative evaluation. Extrahepatic bile duct resection with Roux-en-Y reconstruction was carried out in some patients with LN involvement.

Pathological Evaluation

All the resected and biopsy specimens were examined pathologically for tumor size and number, capsule formation, histological differentiation, the presence of vascular and perineural invasion, and the presence of tumor in LN. The surgical margins were examined for the presence of residual tumor which was described by the residual tumor (R) classification: R0, no residual tumor and resection margin was >0 mm; R1, microscopic residual tumor or resection margin was nil; R2, macroscopic residual tumor.13 , 15 , 17 Each patient was staged according to the 7th edition American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging system for ICC.28 , 29

Follow-Up

After surgery, all patients received regular clinical follow-up including ultrasound scan, liver function tests, and measurement of carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA19-9) and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) at an interval of 1–3 months. Survival was evaluated from the date of surgery; patients were followed for survival until death or the study deadline date of 31 December 2012.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were presented as the mean ± standard deviation. Independence tests were performed using unpaired t test for continuous variables and chi-square or Wilcoxon test for categorical variables. Overall survival (OS) rates were calculated with the Kaplan-Meier method. The possible prognostic factors were analyzed by the univariate analysis and evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by the log-rank test. The multivariate analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model to identify the independent prognostic factors for survival. Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS 19.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Differences with P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Features

A total of 1,372 patients were reviewed, including 1,360 patients with mass-forming (MF) type ICC, 11 patients with intraductal growth type ICC, and one patient with periductal infiltration type ICC according to category of the gross type of ICC by the Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan.30 Because the number of cases was too small and they had different prognosis, the patients with the two latter types of ICC were excluded from the study. Another 27 patients were also excluded due to incomplete survival date. Finally, 1,333 patients with MF type ICC were included in the study. Table 1 describes the patient demographics and clinicopathological features of the ICC. The patients had a mean age of 54 years old, with male dominance. A majority of them (62 %) presented with symptoms such as epigastric pain, weight loss, hepatomegaly, and fever. The most common underlying liver disease in these patients was hepatic B virus infection as indicated by seropositivity for hepatitis B surface antigen (45.6 %); other underlying hepatobiliary diseases included cirrhosis (23.2 %), cholelithiasis (19.3 %), and schistosomiasis (5.3 %), but all the patients had well-compensated liver function. Elevated CA19-9 and CEA were detected in 56.4 and 17.3 % of the patients, respectively. The mean tumor size was 7.1 cm, and most of the patients (64.1 %) presented with solitary tumor. LN metastasis, vascular and perineural invasion, and capsule formation were observed in 28.1, 15.5, 7.3, and 5.8 % of the patients, respectively. According to the 7th AJCC staging system, 38.6 % of the patients were in stage I, 24.5 % in stage II, 7.8 % in stage III, and 29.1 % in stage IV.

Surgical Results

The overall resectability rate was 96.1 % (1,281/1,333); R0, R1, and R2 resections were obtained in 464 (34.8 %), 598 (44.9 %), and 219 (16.4 %) patients, respectively. The 52 (3.9 %) remaining patients had only an exploratory laparotomy with biopsy because of unresectable disease. The types of liver resection included extended right or left hemihepatectomy in 71 (5.6 %) patients, right or left hemihepatectomy in 428 (33.4 %) patients, bisegmentectomy in 528 (41.2 %) patients, and segmentectomy or local resection in 254 (19.8 %) patients; in patients with multiple tumors, anatomic and nonanatomic liver resections were performed in combination depending on the location and the number of the tumors.

LN metastasis, confirmed by final pathological assessment, occurred in 375 (28.1 %) patients and 41 % of them obtained complete LN dissection in addition to liver resection. Most lymphadenectomies were performed around the hepatoduodenal ligament. In patients with ICC originating from the left lobe, LN dissection along common hepatic and left gastric arteries was usually performed additionally, and in a small percentage of patients, LN dissection was even carried out into celiac trunk and para-aortic regions. However, half of the patients with LN metastasis obtained, in addition to liver resection, only a LN biopsy due to more extended nodal involvement such as fixed retropancreatic and celiac or para-aortic LN, which was classified as R2 resection. Another 9 % was among those who had an exploratory laparotomy alone.

Operative death, which was defined as death within 30 days of surgery or death that occurred during same admission period, occurred in eight patients with an operative mortality of 0.6 %. Postoperative complications developed in 153 (11.5 %) patients. According to the Clavien-Dindo classification, grade I complications were observed in 71 (46.4 %) cases, grade II complications in 39 (25.5 %) cases, grade IIIa complications in 19 (12.4 %) cases, grade IIIb complications in 10 (6.5 %) cases, and grade IV complications in 14 (8.2 %) cases. Except for the eight patients who died of hepatic failure or multiple organ failure, all the patients successfully recovered from the complications.

Adjuvant Therapy

Adjuvant chemotherapy was not recommended for patients with R0 resection, while 23.6 % of patients with R1 resection received transarterial chemoembolization 4 weeks after surgery and 10.1 % of the patients with unresectable disease or with R2 resection received adjuvant chemo/radiotherapy. The most common chemotherapy regimen was 5-fluorouracil combined with cisplatin and gemcitabine, and three dimensional conformal radiotherapy was the stander radiation therapy that was used mainly for residual positive LN.

Survival

At a median follow-up period of 19.7 months (range, 1–72 months), the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates for the entire cohort were 58.2, 25.2, and 17.0 %, respectively, with a MST of 14.4 months. On univariate analysis, the presence of HBV infection (P < 0.001) and cirrhosis (P = 0.009), elevated CA19-9 and/or CEA (P < 0.001), tumor size (P < 0.001) and tumor number (P < 0.001), surgical margin status (P < 0.001), the presence of tumor capsule (P < 0.001), LN metastasis (P < 0.001), vascular invasion (P = 0.002), and perineural invasion (P = 0.005) were factors that significantly influenced OS. On multivariate analysis, elevated CA19-9 and/or CEA (P < 0.001), multiple tumors (P < 0.001), positive surgical margin (P < 0.001), lymph node metastasis (P = 0.002), and vascular invasion (P = 0.011) were found to be significant and independent predictors of poor survival, whereas the presence of HBV infection (P < 0.001) and cirrhosis (P = 0.024) were significant and independent predictors of favorable survival (Table 2).

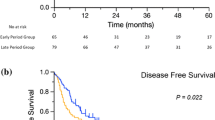

Survival According to the Stages

The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 76.9, 41.4, and 29.0 %, respectively, for patients with stage I (MST, 29.0 months); 66.4, 23.8, and 15.9 % for patients with stage II (MST, 16.0 months); 36.5, 10.6, and 6.0 % for patients with stage III (MST, 10.0 months); and 32.3, 8.1, and 4.0 % for patients with stage IV (MST, 8.0 months). Except between the patients with stage III and stage IV, the survival rates were significantly different between any other two groups of patients (Fig. 1).

Survival According to the Surgical Margin Status

The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 79.1, 42.6, and 28.7 %, respectively, for patients with R0 resection (MST, 30.0 months); 60.5, 20.1, and 13.9 % for patients with R1 resection (MST, 15.0 months); 20.5, 7.4, and 0 % for patients with R2 resection (MST, 6.0 months); and 3.8, 0, and 0 % for patients with an exploratory laparotomy alone (MST, 4.0 months) (Fig. 2). As shown in Table 3, surgical margin status was associated with pathological features of ICC such as tumor size, single or multiple, and presence or absence of capsule formation, vascular invasion, and LN metastasis.

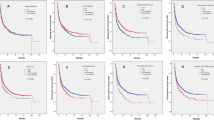

Survival According to the Levels of CA19-9 and CEA

The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates for patients with elevated and normal CA19-9 and/or CEA levels were 46.3, 15.3, and 8.7 % (MST, 11 months) and 75.5, 39.2, 29.0 % (MST, 26 months), respectively (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3a). When patients with elevated CA19-9 and/or CEA were subdivided according to the degree of elevation, those with CA19-9 >1,000 U/ml and/or CEA >100 ng/ml had significant poorer survival than the others with raised CA19-9 and/or CEA below these values, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates being 25, 2.5, 4.3, 2.1 % and 57.3, 21.2, and 12.3 %, respectively (Fig. 3b).

Overall survival (OS) of patients stratified by the level of CA19-9 and/or CEA, lymph node status, tumor number, and vascular invasion. a OS in patients with normal (N = 543) and elevated (N = 790) CA19-9 and/or CEA; b OS in patients with CA19-9 >1,000 U/ml and/or CEA >100 ng/ml (N = 270) and those with elevated CA19-9 and/or CEA below these values (N = 520); c OS in patients with (N = 375) and without (N = 958) lymph node (LN) metastasis; d OS in patients with hepatoduodenal LN metastasis (N = 175) and those with retropancreatic, celiac, or paraaortic LN metastasis besides hepatoduodenal ligament area (N = 200); e OS in patients with single (N = 854) and multiple (N = 479) tumors; f OS in patients with multiple tumors ≤3 (N = 421) and >3 (N = 58); g OS in patients with (N = 206) and without (N = 1127) vascular invasion; h OS in patients with microscopically (N = 100) and macroscopically (N = 106) vascular invasion

Survival According to the LN Status

The patients with LN metastasis had 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates of 33.1, 8.4, and 4.1 %, respectively, with a MST of 9.0 months, significantly lower than those without LN metastasis who had 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates of 68.1, 31.6, and 21.7 %, respectively, with a MST of 19.0 months (Fig. 3c). In the patients with LN metastasis, those (N = 200) with more extended node involvement such as retropancreatic, celiac, or para-aortic LN metastasis had significantly poorer survival than those (N = 175) with hepatoduodenal LN metastasis, the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates being 23.5, 6.4, 0 % and 34.6, 8.6, and 3.7 %, respectively (P = 0.012) (Fig. 3d). The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 52.6, 12.5, and 4.7 %, respectively, for patients receiving LN dissection (MST, 13.0 months) and 23.9, 7.1, and 0 %, respectively, for patients receiving LN biopsy (MST, 7.0 months) (P < 0.001). In the presence of LN metastasis, patients with R0 resection (N = 21) had similar survival as those with R1 resection (N = 127), the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates being 68.2, 22.5, and 0 % (MST, 14 months) and 50.0, 11.1, and 5.3 % (MST, 12 months), respectively (P = 0.266).

Survival According to Tumor Number

Patients with single tumor had the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates of 66.7, 32.2, and 21.2 %, respectively, and those with multiple tumors had the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates of 43.0, 12.2, and 8.2 %, respectively (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3e). In the patients with multiple tumors, those with more than three tumors (N = 58) had significantly poorer survival than those with two to three tumors (N = 421), the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates being 15.5, 6.2, and 3.1 % and 46.8.5, 12.9, and 9.9 %, respectively (Fig. 3f).

Survival According to Tumor Invasion of Blood Vessel

The 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates were 56.8, 16.5, and 9.4 %, respectively, for patients with vascular invasion poorer than those without vascular invasion who had the 1-, 3-, and 5-year OS rates of 58.5, 26.8, and 18.5 %, respectively (P = 0.002) (Fig. 3g). No significant difference in survival was found between patients with macroscopically (N = 106) and microscopically (N = 100) vascular invasion (P = 0.790) (Fig. 3h).

Discussion

It is acknowledged that ICC is associated with poor prognosis poorer than that of HCC after surgical treatment,6 , 17 , 21 , 31 but its actual postoperative prognosis remains less clear owing to a paucity of prognostic data for ICC. To our knowledge, the present series is one of the largest in the literature, so the results of our study would most likely reflect the current status of surgical treatment of ICC which, as documented by our results, is indeed not encouraging.

Guideline for the treatment of ICC has not been developed; in our current clinical practice (and that of others,5 , 7 , 12 , 13) surgical resection was attempted whenever possible.29 As shown in the present study, this strategy led to ICC resection with varied surgical radicality, including R0, R1, R2 resections and even exploratory laparotomy with only biopsy. There is a significant discrepancy from center to center in the rates of R0 resection for ICC ranging from 19.8 to 80.0 %,6 , 13 , 15 , 17 , 26 , 31 , 32 which appears to depend mainly on the indications for resection because there is a corresponding difference in the resectability rates ranging from 18 to 77 %.4 – 6 , 8 , 13 , 16 , 17 , 31 The overall resectability rate in the present study reached 96.1 %, the highest in the literature which might partly account for relatively low R0 resection rate (34.8 %) achieved in the current series. A lower R0 resection rate would be expected when surgery was indicated for all potential resectable ICC because, as shown in Table 3, most patients with R0 resection had single, smaller tumors with favorable pathological characteristics and at earlier stages, whereas most potential resectable ICC were larger or multiple with LN or vascular involvement at time of surgery, and for patients with such tumors, it is often difficult to obtain an adequate safety margin. Whether more aggressive surgery to increase R0 resection rate could improve the prognosis of ICC requires further validation.5 , 13 , 15 , 17 , 33

Our study clearly demonstrated that the patients with different margin status had significant different survival (Fig. 2). As expected, R0 resection offered the most advantageous outcome, with a 5-year OS rate of 28.1 % and a MST of 30 months. Interestingly, there exists remarkable difference in 5-year survival following R0 resection of ICC between Western and Eastern countries, with much higher survival (39–63 %) reported from Europe and America.12 , 13 , 16 , 34 In present series, we observed a relatively low 5-year survival after R0 resection (28.1 %), but it was comparable to that reported from Asia (22.0–33.9 %).18 , 20 , 26 , 35 Maybe there is a possibility that ICC differs in biological features between Western and Eastern world as in this cohort, we observed remarkably more ICC (59.3 %) associated with elevated CA19-9 and/or CEA than those reported from Western world.12 , 14 , 36 , 37 Elevation of CA19-9 and/or CEA was found in this study to be an independently prognostic factor for poorer survival (Table 2) (Fig. 3a). Moreover, we found that the higher the level of elevated CA19-9 and/or CEA, the poorer the prognosis of ICC; patients with CA19-9 >1,000 U/ml and/or CEA >100 ng/ml had significant worse survival than those with elevated CA19-9 and/or CEA below these values (Fig. 3b).

There have been controversies about the influence of R1 resection on patient survival. Although most studies looking at the significance of resection margin on survival showed that R1 status was a negative predictive factor,5 , 16 , 36 , 38 , 39 it was also reported that the effect of an R1 resection was not statistically significant in terms of survival,13 , 15 and a higher survival was even observed in R1-resected patients as compared to those with R0 resection.17 These conflicting results were usually retrieved from studies with limited number of cases which might result in misleading conclusions. The present study, using a large cohort of patients, revealed that R1 resection had a profound negative impact on survival, with R1-resected patients having a MST of 15 versus 30 months for patients with R0 resection (P < 0.001).

The justification for R2 resection, which occurred in 16 % of our patients, has been highly controversial. Some authors reported that R2 resection did not provide any survival benefit except the risks of major hepatic surgery,5 , 9 , 36 whereas others believed that some patients could benefit from R2 resection.16 , 40 In our series, the patients with R2 resection, in fact, could be subdivided into those with residual tumor in the LN and those with residual tumor in the liver, and we found that only the former survived significantly longer than the patients undergoing exploratory laparotomy; patients with residual tumor in the liver had a similar disappointing survival as those with exploratory laparotomy alone. This finding suggested that R2 resection due to residual positive LN might offer a survival advantage over laparotomy but not when macroscopic tumors were left in the liver.

Using the 7th AJCC staging system, our patients were stratified into discrete prognostic groups except between those with stage III and stage IV (Fig. 1). The 7th AJCC staging system includes the number but not the size of tumors as a factor for staging ICC.28 , 29 Conflicting results exist regarding whether tumor size is a relevant prognostic factor.14 , 37 , 41 – 43 On univariate analysis in this study, both the number and the size of tumors were factors that significantly influenced the OS; however, only the number of tumor independently influenced patients’ survival on multivariate analysis (Table 2), confirming some earlier observations.28 , 29 , 41 Moreover, our study also showed that among patients with multiple tumors, those with more than three tumors had even more dismal survival as compared with those with two to three tumors (Fig. 3e, f).

Among the components of AJCC staging system, LN status is the most important prognostic factor, probably due to the fact that LN metastasis is one of the important biological features of ICC.20 , 29 , 32 The true incidence of LN metastasis among all patients undergoing surgery for ICC remains unclear estimated between 20 and 0 %19 because lymphadenectomy is currently not routinely performed for LN evaluation during ICC surgery.12 , 44 In the current study, we performed LN dissection when pre- and intraoperative evaluation suggested a N1 disease, and LN metastasis was found in 28.1 % of the entire cohort, which was very close to 29.8 % (74/248) of N1 incidence revealed by routine lymphadenectomy for LN evaluation,19 suggesting the risk of undetectable occult N1 is very small following preoperative imaging evaluation and intraoperative macroscopical assessment.16 , 45 Nevertheless, routine LN evaluation should be considered in patients undergoing resection of ICC at least in the hepatoduodenal ligament area.

Our data, consistent with previous reports,13 , 16 , 20 , 29 , 32 , 35 , 37 showed that LN metastasis was a significant independent variable that unfavorably influenced the prognosis of ICC (Table 1) (Fig. 3c). Patients with LN metastasis had significantly poorer survival compared with those without LN metastasis and, moreover, patients with extended LN metastasis extra the hepatoduodenal ligament area had even worse survival than those with LN metastasis around the hepatoduodenal ligament (Fig. 3d) due to the fact that in the majority of the former LN dissection was impossible. We also found that, in the presence of LN metastasis, patients had similar survival whether they obtained R0 or R1 resection. This result might partly explain the reported conflicting results about the influence on patient survival of resection margins (R0 or R1),5 , 13 , 15 – 17 , 38 , 39 i.e., resection margin status had a significant influence on survival only in the patients without LN metastasis.13 Surgical therapy for ICC with LN metastasis is still a controversy and not standardized,20 , 45 and debate also exists for whether LN dissection could necessarily contribute to prolong long-term survival.33 , 37 , 46 – 48 In the current series, patients obtained LN dissection survived significantly longer than those with LN biopsy (MST, 13 versus 6 months), indicating that LN dissection should be performed when possible even though, as shown by our study, only a small subset of such patients could obtain long-term survival.

Two limits to this study need to be acknowledged. First, it is a retrospective study, although containing the largest and most current case series of ICC patients treated surgically. Second, we do not routinely perform lymphadenectomy for LN evaluation, and the patients without LN metastasis in our current series are actually Nx patients who were assumed to have N0 disease, so their survival results should be interpreted with caution even though the N1 incidence in our series is very close to that of pN1 reported in the literature.

In conclusion, R0 resection offers the best possibility of long-term survival, but the chance of a R0 resection is low when surgery is performed for potential resectable ICC, which might explain the present unsatisfactory results in surgical treatment of ICC. From the analysis of our data, R1 resection, including R2 resection in some cases, can be performed because it offers better survival than laparotomy alone, and LN dissection should be performed in cases with N1 disease as it can prolong such patients’ survival compared with those with residual positive node. However, a MST of 12.9 months was recently reported for unresectable ICC by palliative chemoradiotherapy25; this result is comparable to ours achieved in patients with N1 disease by liver resection coupled with LN dissection (MST, 13 months), suggesting that, in the era of effective chemoradiotherapy,49 , 50 it seems necessary to modify current surgical treatment strategy for ICC. As revealed in the present large cohort study, the potentially resectable ICC could be divided into different subgroups according to the independent predictive factors and further randomized controlled trials comparing surgical with nonsurgical treatment in the subgroups of ICC patients, which will become feasible with increasing incidence of ICC, will help define the reasonable indications for surgery in the management of ICC.

References

Patel T. Cholangiocarcinoma--controversies and challenges. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;8:189–200.

Khan SA, Thomas HC, Davidson BR, Taylor-Robinson SD. Cholangiocarcinoma. Lancet 2005;366:1303–14.

Poultsides GA, Zhu AX, Choti MA, Pawlik TM. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Surg Clin North Am 2010;90:817–37.

Sempoux C, Jibara G, Ward S, Fan C, Qin L, Roayaie S et al. Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: New Insights in Pathology. Seminars in Liver Disease 2011;31:049–60.

Lang H, Sotiropoulos GC, Fruhauf NR, Domland M, Paul A, Kind EM et al. Extended hepatectomy for intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma (ICC): when is it worthwhile? Single center experience with 27 resections in 50 patients over a 5-year period. Ann Surg 2005;241:134–43.

Endo I, Gonen M, Yopp AC, Dalal KM, Zhou Q, Klimstra D et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: rising frequency, improved survival, and determinants of outcome after resection. Ann Surg 2008;248:84–96.

Tan JC, Coburn NG, Baxter NN, Kiss A, Law CH. Surgical management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma--a population-based study. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:600–8.

Jonas S, Thelen A, Benckert C, Biskup W, Neumann U, Rudolph B et al. Extended liver resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: A comparison of the prognostic accuracy of the fifth and sixth editions of the TNM classification. Ann Surg 2009;249:303–9.

Roayaie S, Guarrera JV, Ye MQ, Thung SN, Emre S, Fishbein TM et al. Aggressive surgical treatment of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: predictors of outcomes. J Am Coll Surg 1998;187:365–72.

Meyer CG, Penn I, James L. Liver transplantation for cholangiocarcinoma: results in 207 patients. Transplantation 2000;69:1633–7.

Weimann A, Varnholt H, Schlitt HJ, Lang H, Flemming P, Hustedt C et al. Retrospective analysis of prognostic factors after liver resection and transplantation for cholangiocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg 2000;87:1182–7.

DeOliveira ML, Cunningham SC, Cameron JL, Kamangar F, Winter JM, Lillemoe KD et al. Cholangiocarcinoma: thirty-one-year experience with 564 patients at a single institution. Ann Surg 2007;245:755–62.

Farges O, Fuks D, Boleslawski E, Le Treut YP, Castaing D, Laurent A et al. Influence of surgical margins on outcome in patients with intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicenter study by the AFC-IHCC-2009 study group. Ann Surg 2011;254:824–9.

Uenishi T, Yamazaki O, Yamamoto T, Hirohashi K, Tanaka H, Tanaka S et al. Serosal invasion in TNM staging of mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2005;12:479–83.

Shimada K, Sano T, Sakamoto Y, Esaki M, Kosuge T, Ojima H. Clinical impact of the surgical margin status in hepatectomy for solitary mass-forming type intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma without lymph node metastases. J Surg Oncol 2007;96:160–5.

Konstadoulakis MM, Roayaie S, Gomatos IP, Labow D, Fiel MI, Miller CM et al. Fifteen-year, single-center experience with the surgical management of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: operative results and long-term outcome. Surgery 2008;143:366–74.

Tamandl D, Herberger B, Gruenberger B, Puhalla H, Klinger M, Gruenberger T. Influence of hepatic resection margin on recurrence and survival in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2008;15:2787–94.

Shirabe K, Mano Y, Taketomi A, Soejima Y, Uchiyama H, Aishima S et al. Clinicopathological prognostic factors after hepatectomy for patients with mass-forming type intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: relevance of the lymphatic invasion index. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1816–22.

de Jong MC, Nathan H, Sotiropoulos GC, Paul A, Alexandrescu S, Marques H et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: an international multi-institutional analysis of prognostic factors and lymph node assessment. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:3140–5.

Uchiyama K, Yamamoto M, Yamaue H, Ariizumi S, Aoki T, Kokudo N et al. Impact of nodal involvement on surgical outcomes of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a multicenter analysis by the Study Group for Hepatic Surgery of the Japanese Society of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreatic Surgery. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci 2011;18:443–52.

Li YY, Li H, Lv P, Liu G, Li XR, Tian BN et al. Prognostic value of cirrhosis for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after surgical treatment. J Gastrointest Surg 2011;15:608–13.

Nanashima A, Sumida Y, Abo T, Nagasaki T, Takeshita H, Fukuoka H et al. Patient outcome and prognostic factors in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after hepatectomy. Hepatogastroenterology. 2007;54(80):2337–42.

Jan YY, Yeh CN, Yeh TS, Chen TC. Prognostic analysis of surgical treatment of peripheral cholangiocarcinoma: two decades of experience at Chang Gung Memorial Hospital. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(12):1779–84.

Nathan H, Pawlik TM, Wolfgang CL, Choti MA, Cameron JL, Schulick RD. Trends in survival after surgery for cholangiocarcinoma: a 30-year population-based SEER database analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:1488–96.

Dhanasekaran R, Hemming AW, Zendejas I, Treatment outcomes and prognostic factors of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2013;29(4):1259–67.

Wang Y, Li J, Xia Y, Gong R, Wang K, Yan Z et al. Prognostic nomogram for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after partial hepatectomy. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:1188–95.

Shaib YH, Davila JA, McGlynn K, El-Serag HB. Rising incidence of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States: a true increase? J Hepatol 2004;40:472–7.

Edge SB, Compton CC. The American Joint Committee on Cancer: the 7th edition of the AJCC cancer staging manual and the future of TNM. Ann Surg Oncol 2010;17:1471–4.

Nathan H, Pawlik TM. Staging of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010;26:269–73.

The general rules for the clinical and pathological study of primary liver cancer. Liver Cancer Study Group of Japan. Jpn J Surg 1989; 19:98–129.

Zhou XD, Tang ZY, Fan J, Zhou J, Wu ZQ, Qin LX et al. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: report of 272 patients compared with 5,829 patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 2009;135:1073–80.

Tamandl D, Kaczirek K, Gruenberger B, Koelblinger C, Maresch J, Jakesz R et al. Lymph node ratio after curative surgery for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg 2009;96:919–25.

Ohtsuka M, Ito H, Kimura F, Shimizu H, Togawa A, Yoshidome H et al. Results of surgical treatment for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and clinicopathological factors influencing survival. Br J Surg 2002;89:1525–31.

Sotiropoulos GC, Bockhorn M, Sgourakis G, Brokalaki EI, Molmenti EP, Neuhäuser M et al. R0 liver resections for primary malignant liver tumors in the noncirrhotic liver: a diagnosis-related analysis. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54(4):887–94.

Zhou HB, Wang H, Li YQ, Li SX, Zhou DX, Tu QQ et al. Hepatitis B virus infection: a favorable prognostic factor for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma after resection. World J Gastroenterol 2011;17:1292–1303.

Puhalla H, Schuell B, Pokorny H, Kornek GV, Scheithauer W, Gruenberger T. Treatment and outcome of intrahepatic cholangiocellular carcinoma. Am J Surg 2005;189:173–7.

Nakagawa T, Kamiyama T, Kurauchi N, Matsushita M, Nakanishi K, Kamachi H et al. Number of lymph node metastases is a significant prognostic factor in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. World J Surg 2005;29:728–33.

Paik KY, Jung JC, Heo JS, Choi SH, Choi DW, Kim YI. What prognostic factors are important for resected intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma? J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008;23:766–70.

Miwa S, Miyagawa S, Kobayashi A, Akahane Y, Nakata T, Mihara M et al. Predictive factors for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma recurrence in the liver following surgery. J Gastroenterol 2006;41:893–900.

Lang H, Sotiropoulos GC, Sgourakis G, Schmitz KJ, Paul A, Hilgard P et al. Operations for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: single-institution experience of 158 patients. J Am Coll Surg 2009;208:218–28.

Nathan H, Aloia TA, Vauthey JN, Abdalla EK, Zhu AX, Schulick RD et al. A proposed staging system for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Ann Surg Oncol 2009;16:14–22.

Morimoto Y, Tanaka Y, Ito T, Nakahara M, Nakaba H, Nishida T et al. Long-term survival and prognostic factors in the surgical treatment for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg 2003;10:432–40.

Okabayashi T, Yamamoto J, Kosuge T, Shimada K, Yamasaki S, Takayama T et al. A new staging system for mass-forming intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: analysis of preoperative and postoperative variables. Cancer 2001;92:2374–83.

Patel T. Increasing incidence and mortality of primary intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma in the United States. Hepatology. 2001;33:1353–7.

Grobmyer SR, Wang L, Gonen M, Fong Y, Klimstra D, D’Angelica M et al. Perihepatic lymph node assessment in patients undergoing partial hepatectomy for malignancy. Ann Surg. 2006;244(2):260–4.

Shimada M, Yamashita Y, Aishima S, Shirabe K, Takenaka K, Sugimachi K. Value of lymph node dissection during resection of intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Br J Surg 2001;88:1463–6.

Uenishi T, Hirohashi K, Kubo S, Yamamoto T, Yamazaki O, Shuto T et al. Clinicopathologic features in patients with long-term survival following resection for intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Hepatogastroenterology 2003;50:1069–72.

Inoue K, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, Torzilli G, Yamamoto J, Shimada K et al. Long-term survival and prognostic factors in the surgical treatment of mass-forming type cholangiocarcinoma. Surgery 2000;127:498–505.

Rana A, Hong JC. Orthotopic liver transplantation in combination with neoadjuvant therapy: a new paradigm in the treatment of unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2012;28:258–65.

Zeng ZC, Tang ZY, Fan J, Zhou J, Qin LX, Ye SL et al. Consideration of the role of radiotherapy for unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: a retrospective analysis of 75 patients. Cancer J 2006;12:113-22.

Conflict of interest

There is no potential conflict of interest for the individual authors, study participants, or any company.

Funding

We have no sources of funding for research and/or publication of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Xian-wu Luo and Lei Yuan contributed equally to this work.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luo, X., Yuan, L., Wang, Y. et al. Survival Outcomes and Prognostic Factors of Surgical Therapy for All Potentially Resectable Intrahepatic Cholangiocarcinoma: a Large Single-Center Cohort Study. J Gastrointest Surg 18, 562–572 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2447-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-013-2447-3