Abstract

Purpose

We conducted a meta-analysis to evaluate and compare the short- and long-term results of laparoscopy-assisted and open rectal surgery for the treatment of patients with rectal cancer.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Science Citation Index, and the Cochrane Controlled Trial Register for relevant papers published between January 1990 and April 2011 by using the search terms “laparoscopy,” “laparoscopy assisted,” “surgery,” “rectal cancer,” and “randomized controlled trials.” We analyzed outcomes over short- and long-term periods.

Results

We identified 12 papers reporting results from randomized controlled trials that compared laparoscopic surgery with open surgery for rectal cancer. Our meta-analysis included 2,095 patients with rectal cancer; 1,096 had undergone laparoscopic surgery, and 999 had undergone open surgery. In the short-term period, 13 outcome variables were examined. In the long-term period, eight oncologic variables, as well as late morbidity, urinary function, and sexual function were analyzed. Laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer was associated with a reduction in intraoperative blood loss and the number of transfused patients, earlier resumption of oral intake, and a shorter duration of hospital stay over the short-term, but with similar short-term and long-term oncologic outcomes compared to conventional open surgery.

Conclusions

Laparoscopic surgery may be an acceptable alternative treatment option to conventional open surgery for rectal cancer.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer has been reported to achieve superior short-term outcomes, including earlier postoperative recovery, less postoperative morbidity,1,2 and better quality of life,3 compared with conventional open surgery for rectal cancer. The use of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer has recently become more widespread, and several articles have described long-term outcomes associated with the procedure.4–9 However, the curability of rectal cancer using laparoscopic surgery is controversial because the long-term oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic surgery, such as overall mortality, cancer-related mortality, and recurrence rate, remain uncertain. Laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer is a technically demanding procedure because the surgical space of the rectum is a narrow pelvic cavity surrounded by solid bones, which prevents the manipulation of laparoscopic instruments.

A radical excision of rectal cancers includes high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery for adequate lymphatic clearance and total mesorectal excision. It is difficult to assess the quality of total mesorectal excision in rectal cancer surgery; however, the rates of circumferential resection margin and distal resection margin involvement are the best direct measure of total mesorectal excision.10 The conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in colorectal cancer (CLASICC) trial reported the importance of the circumferential resection margin.8 The study showed that a conversion to an open from a laparoscopic surgery was associated with a significantly worse overall, but not disease-free, survival. To accurately evaluate the efficacy of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer, the short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic surgery must be compared to those of open surgery. For short-term outcomes, perioperative variables, pathologic factors, and the cost of surgery should be examined. For long-term outcomes, long-term oncologic results are the primary endpoint of interest, followed by late morbidity and quality of life. Recently, several randomized controlled trials comparing laparoscopic surgery with open surgery for rectal cancer have been published.11–18 We conducted a meta-analysis of the data from these randomized controlled trials to compare the short- and long-term outcomes of laparoscopic and open surgery for rectal cancer.

Materials and Methods

Literature Search

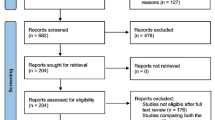

To identify papers relevant to our study, we searched the major medical databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, Science Citation Index, and the Cochrane Controlled Trial Register for studies published between January 1990 and April 2011. The following search terms were used: “laparoscopy,” “laparoscopy assisted,” “surgery,” “rectal cancer,” and “randomized controlled trials.” We treated studies that were part of a series as a single study.7–9,11,19,20 Appropriate data from such study series were used for this meta-analysis. This meta-analysis was prepared in accordance with the Quality of Reporting of Meta-analyses statement21 (Fig. 1).

Inclusion Criteria

To enter this meta-analysis, studies had to: (1) be described in English, (2) be a randomized controlled trial, (3) compare laparoscopic and open conventional surgery for rectal cancer, and (4) report on at least one of the outcome measures mentioned below.

Exclusion Criteria

Studies were excluded from this analysis if (1) the outcomes of interest were not reported for the two surgical techniques and if (2) they reported on rectal surgery for benign lesions.

Data Extraction

Three researchers (H.O., Y.T., and K.H.) extracted data from each article by using a structured sheet and entered the data into a database. Because this analysis was performed on the principle of intention-to-treat,22 all patients converted from the laparoscopic group to the open group remained in the laparoscopic group for analysis. We conducted separate meta-analyses for two different postoperative time periods: short-term and long-term. For the short-term analysis, we collected data on operation time, estimated blood loss, number of transfused patients, number of dissected lymph nodes, hospital stay, time to oral diet, period of parenteral analgesic administration, overall complications, anastomotic leakage, perioperative mortality, circumferential resection margin, distal resection margin, and cost of surgery. The cost of surgery consisted of operating and hospitalization costs. We also examined the relationship between the conversion rate from laparoscopic to open surgery and single-institution versus multicenter trials. For the oncologic results in the long-term analysis, we used data on the rate of overall recurrence, local recurrence, distant metastasis, wound site recurrence, cancer-related mortality, overall mortality, and disease-free survival at 3 and 5 years after surgery. For late morbidity in the long-term analysis, we used data on the rate of overall late morbidity, ileus, and incisional hernia. For quality of life in the long-term analysis, we used data on urinary and sexual dysfunction. Where necessary, we contacted the authors of the original papers to receive further information.

Assessment of Study Quality

The quality of the randomized controlled trials was assessed using Jadad’s scoring system.23 Two reviewers (H.O., Y.T.) assessed all studies that met the inclusion criteria (Table 1).

Statistical Analysis

Weighted mean differences and odds ratios were used for the analysis of continuous and dichotomous variables, respectively. Random effects models were used to identify heterogeneity between the studies,24 and the degree of heterogeneity was assessed using the chi-square test. For the analysis of the conversion rate, the chi-square test was used. The confidence interval (CI) was established at 95%, and p values of less than 0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance. As the cost data of one article19 were precious and had neither a range nor any other measure of dispersion, the standard deviation was estimated by halving the mean.25 One Euro and British pound were converted to US $1.4 and US $1.6, respectively. The statistical analyses were performed using the Review Manager (RevMan) software, version 5.1.1, provided by the Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark.

Results

We identified 12 papers reporting results of randomized controlled trials that compared laparoscopic and open surgery for rectal cancer.3–18 The characteristics of each randomized controlled trial are presented in Table 1. Our meta-analysis included 2,095 patients with rectal cancer; of these, 1,096 had undergone laparoscopic surgery, and 999 had undergone conventional open surgery. Short-term and long-term results are shown in Figs. 2 and 3, respectively. Late morbidity rate, urinary dysfunction, and sexual dysfunction are shown in Fig. 4.

Short-Term Outcomes

The operative time for laparoscopic surgery was significantly greater, by 40.96 min, than that for open surgery (weighted mean difference = 40.96; 95% CI = 25.53–56.38; p < 0.00001). The intraoperative blood loss and the number of transfused patients in the laparoscopic group were significantly lower than in the open group. There was no significant difference in the number of harvested lymph nodes. The duration of hospital stay and the time to oral diet were significantly shorter with laparoscopic surgery than open surgery (p = 0.0001 and 0.02, respectively). There was no significant difference in the period of parenteral analgesic administration. Overall complications and anastomotic leakage did not differ significantly between the two groups. We found no significant difference between patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery and those who underwent conventional open surgery for perioperative mortality.

Positive Circumferential Resection Margin

Seven articles reported data on the circumferential resection margin. Five of these compared data between laparoscopic and open groups. All five articles reported that there was no significant difference in the positive circumferential resection margin between the two groups. In an analysis of pooled data, we found that there was no significant difference in the positive circumferential resection margin between the two groups. There was no significant difference in the distal resection margin.

Cost of Surgery

In an analysis of the cost of surgery, there was no significant difference between the two groups. The cost of open surgery was similar among the three articles that assessed open surgery cost.

Conversion Rate

Ten articles reported data on the conversion rate from laparoscopic to open surgery, which ranged from 0% to 34% (Table 1). In an analysis of the conversion rate, there was no significant difference between the trials performed by a single institution and those performed on a multicenter basis (p = 0.51).

Long-Term Outcomes

First, oncologic results of the long-term period were examined. Second, long-term morbidity and quality of life were evaluated.

Tumor Recurrence

Eight, eight, and seven articles reported data on overall recurrence, local recurrence, and distant metastasis, respectively. Four, five, and four articles, respectively, compared these variables between laparoscopic and open surgery groups; none reported any significant difference. In an analysis of the pooled data, we found no significant difference in the overall recurrence, local recurrence, and distant metastasis between patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery and those who underwent open surgery. Further, no significant difference was found for wound site recurrence using the pooled data.

Mortality

Seven, five, two, and four articles reported data on overall mortality, cancer-related mortality, disease-free survival at 3 years after surgery, and that at 5 years, respectively. Five, two, one, and four articles, respectively, compared these variables between laparoscopic and open surgery groups; none reported any significant difference. In an analysis of the pooled data, we found no significant difference in the overall mortality, cancer-related mortality, and disease-free survival at 3 and 5 years after surgery between patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery and those who underwent conventional open surgery.

Long-Term Morbidity

Two, three, and three articles reported data on overall late morbidity, ileus, and incisional hernia, respectively. In an analysis of the pooled data, the rate of overall late morbidity in the laparoscopic group was significantly lower than that in the open group (odds ratio = 0.31; 95% CI = 0.14–0.67; p = 0.003); however, we found no significant difference for ileus and incisional hernia between the two groups.

Long-Term Quality of Life

Three and two articles reported data on urinary and sexual dysfunction, respectively.

Urinary dysfunction did not differ significantly between the two groups (odds ratio = 1.11; 95% CI = 0.57–2.19; p = 0.75). There was no significant difference in male, female, and both male and female sexual dysfunction between laparoscopic and open groups.

Heterogeneity

In the short-term period, a significant heterogeneity was found between studies with respect to operative time, duration of hospital stay, time to oral diet, and cost of surgery. In the long-term period, we found no significant heterogeneity between studies.

Discussion

In this meta-analysis, the examination of short-term outcomes showed that laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer is associated with a significantly longer operative time, but significantly less intraoperative blood loss and the number of transfused patients compared with conventional open surgery. These results are consistent with those of recent randomized controlled trials.3,6,12 Potential explanations for the abovementioned results include meticulous dissection facilitated by instruments for laparoscopic surgery and videoscopic magnification.26–28 Patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer resumed oral intake significantly earlier and had significantly shorter hospital stays than did patients who underwent conventional open surgery; this finding suggests that laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer leads to faster recovery. In this meta-analysis, there was no significant difference in the period of parenteral analgesic administration between the two groups; however, Ng et al. reported that the number of postoperative analgesic requirements was significantly lower following laparoscopic surgery than conventional open surgery, both for upper and low rectal cancer.14,15 The shorter surgical wound in laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer may reduce the number of postoperative analgesic requirements, but not the duration of analgesic administration. No significant difference was found for overall perioperative complications, anastomotic leakage, and perioperative mortality between the two surgery groups; this finding suggests that the safety and feasibility of a laparoscopic surgery is similar to that of a conventional open surgery for rectal cancer. Further, the quality of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer appears to be similar to that of conventional open surgery, as shown by an insignificant difference in the number of dissected lymph nodes16 and the rate of positive circumferential resection margin and distal resection margin10 in this meta-analysis and previous studies.5,13,15 In the analysis of the cost of surgery, we found no significant overall difference between laparoscopic and open surgery. The cost of open surgery for rectal cancer was similar among the three articles that assessed open surgery costs.12,14,19 However, the operating costs were higher, and the hospitalization costs were lower for laparoscopic surgery compared with open surgery.

Several reports have shown that conversion from laparoscopic to open surgery is associated with inferior surgical outcomes.11,29 In this analysis, the conversion rate was not significantly related to the type of study, i.e., single institution or multicenter. Both the CLASICC trial and Stohlein et al. reported that tumor infiltration/fixation and obesity were the most common reasons for conversion.11,29

In the long-term period, we found no significant difference in the overall recurrence, local recurrence, and distant metastasis between the two surgery groups. There was also no significant difference in wound site recurrence between the two groups, with the rate of wound site recurrence very small in the laparoscopic and open surgery groups. No significant difference was found in overall mortality, cancer-related mortality, and disease-free survival at 3 and 5 years after surgery. The abovementioned findings suggest that laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer is comparable to conventional open surgery with respect to long-term oncologic results.

In the evaluation of long-term morbidity, the morbidity rate following laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer was found to be significantly lower than that following conventional open surgery. Similarly, Ng et al. and Braga et al. described a high rate of adhesion-related bowel obstruction15 and incisional hernia6 in the conventional open surgery group, respectively, compared with the laparoscopic surgery group. No significant difference was found in the analysis of pooled data for the incidence of ileus between the two groups. There also was no significant difference in the analysis of pooled data for the rate of incisional hernia between the two surgery groups.

Urinary dysfunction and sexual dysfunction were examined in this analysis to evaluate long-term quality of life. Injury to the autonomic nervous system causes variable symptoms of bladder and sexual dysfunction.30–32 The incidence of bladder and sexual dysfunction in patients with rectal cancer has diminished since total mesorectal excision was introduced and the need to preserve the autonomic nervous system was recognized.32,33 However, few randomized controlled trials have reported data on urinary and sexual dysfunction in this patient population.17,20 No significant difference was found in the analysis of pooled data for urinary dysfunction between laparoscopic and open surgery groups, which compares favorably with other reports. Further, in this meta-analysis, no significant differences were detected in the analysis of pooled data for male, female, and male and female sexual dysfunction, whereas Jayne et al. reported a trend towards worse male sexual dysfunction20 and Quah et al. described a higher rate of male sexual dysfunction17 in laparoscopic surgery compared with open surgery groups. In the CLASICC trial, total mesorectal excision was found to be more commonly performed in laparoscopic surgery than conventional open surgery, which was postulated to be the reason for the worse postoperative sexual function in men who underwent laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer.20 On the other hand, there is an idea that laparoscopic total mesorectal excision will allow for better preservation of the pelvic nervous system because the magnified view of the pelvis under the laparoscope allows for easier identification of pelvic nerves.34,35 Because of the limited data, it is difficult to accurately quantify the influence of laparoscopic surgery on sexual function.

A significant heterogeneity between studies was observed only for short-term outcomes, including operative time, duration of hospital stay, time to oral diet, and cost of surgery. In the long-term period, we found no significant heterogeneity between studies. The reason for the observed heterogeneity in operative time may be variations in the skill of the surgeon and the condition of the tumor. Differences in the clinical approach at different institutions may have caused the heterogeneity in the duration of hospital stay and time to oral diet. Reasons for the heterogeneity in the cost of surgery may include variations in operative time and the cost of laparoscopic instruments.

In conclusion, this meta-analysis showed that laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer is associated with a reduction in intraoperative blood loss and the number of transfused patients, earlier resumption of oral intake, and shorter duration of hospital stay over the short-term, but is associated with similar short-term and long-term oncologic outcomes compared to conventional open surgery. Therefore, laparoscopic surgery may be an acceptable alternative treatment option to conventional open surgery for rectal cancer.

References

Aziz O, Constantinides V, Tekkis PP, Athanasiou T, Purkayastha S, Paraskeva P, Darzi AW, Heriot AG. Laparoscopic versus open surgery for rectal cancer: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:413–424.

Gao F, Cao YF, Chen LS. Meta-analysis of short-term outcomes after laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2006;21:652–656.

Kang SB, Park JW, Jeong SY, Nam BH, Choi HS, Kim DW, Lim SB, Lee TG, Kim DY, Kim JS, Chang HJ, Lee HS, Kim SY, Jung KH, Hong YS, Kim JH, Sohn DK, Kim DH, Oh JH. Open versus laparoscopic surgery for mid or low rectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy (COREAN trial): short-term outcomes of an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:637–645.

Araujo SE, da Silva eSousa AH Jr, de Campos FG, Habr-Gama A, Dumarco RB, Caravatto PP, Nahas SC, da Silva J, Kiss DR, Gama-Rodrigues JJ. Conventional approach x laparoscopic abdominoperineal resection for rectal cancer treatment after neoadjuvant chemoradiation: results of a prospective randomized trial. Rev Hosp Clin Fac Med Sao Paulo. 2003;58:133–140.

Baik SH, Gincherman M, Mutch MG, Birnbaum EH, Fleshman JW. Laparoscopic vs open resection for patients with rectal cancer: comparison of perioperative outcomes and long-term survival. Dis Colon Rectum. 2011;54:6–14.

Braga M, Frasson M, Vignali A, Zuliani W, Capretti G, Di Carlo V. Laparoscopic resection in rectal cancer patients: outcome and cost-benefit analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:464–471.

Jayne DG, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H, Quirke P, Copeland J, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM; UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. Randomized trial of laparoscopic-assisted resection of colorectal carcinoma: 3-year results of the UK MRC CLASICC Trial Group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:3061–3068.

Jayne DG, Thorpe HC, Copeland J, Quirke P, Brown JM, Guillou PJ. Five-year follow-up of the Medical Research Council CLASICC trial of laparoscopically assisted versus open surgery for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1638–1645.

Mirza MS, Longman RJ, Farrokhyar F, Sheffield JP, Kennedy RH. Long-term outcomes for laparoscopic versus open resection of nonmetastatic colorectal cancer. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:679–685.

Poon JT, Law WL. Laparoscopic resection for rectal cancer: a review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:3038–3047.

Guillou PJ, Quirke P, Thorpe H, Walker J, Jayne DG, Smith AM, Heath RM, Brown JM; MRC CLASICC trial group. Short-term endpoints of conventional versus laparoscopic-assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:1718–1726.

Arteaga González I, Díaz Luis H, Martín Malagón A, López-Tomassetti Fernández EM, Arranz Duran J, Carrillo Pallares A (2006) A comparative clinical study of short-term results of laparoscopic surgery for rectal cancer during the learning curve. Int J Colorectal Dis. 21:590–595.

Lujan J, Valero G, Hernandez Q, Sanchez A, Frutos MD, Parrilla P. Randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic and open surgery in patients with rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2009;96:982–989.

Ng SS, Leung KL, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Li JC, Teoh AY, Leung WW. Laparoscopic-assisted versus open abdominoperineal resection for low rectal cancer: a prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2418–2425.

Ng SS, Leung KL, Lee JF, Yiu RY, Li JC, Hon SS. Long-term morbidity and oncologic outcomes of laparoscopic-assisted anterior resection for upper rectal cancer: ten-year results of a prospective, randomized trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:558–566.

Park IJ, Choi GS, Lim KH, Kang BM, Jun SH. Laparoscopic resection of extraperitoneal rectal cancer: a comparative analysis with open resection. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1818–1824.

Quah HM, Jayne DG, Eu KW, Seow-Choen F. Bladder and sexual dysfunction following laparoscopically assisted and conventional open mesorectal resection for cancer. Br J Surg. 2002;89:1551–1556.

Zhou ZG, Hu M, Li Y, Lei WZ, Yu YY, Cheng Z, Li L, Shu Y, Wang TC. Laparoscopic versus open total mesorectal excision with anal sphincter preservation for low rectal cancer. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1211–1215.

Franks PJ, Bosanquet N, Thorpe H, Brown JM, Copeland J, Smith AM, Quirke P, Guillou PJ; CLASICC trial participants. Short-term costs of conventional vs laparoscopic assisted surgery in patients with colorectal cancer (MRC CLASICC trial). Br J Cancer. 2006;95:6–12.

Jayne DG, Brown JM, Thorpe H, Walker J, Quirke P, Guillou PJ. Bladder and sexual function following resection for rectal cancer in a randomized clinical trial of laparoscopic versus open technique. Br J Surg. 2005;92:1124–1132.

Moher D, Cook DJ, Eastwood S, Olkin I, Rennie D, Stroup DF. Improving the Quality of Reports of Meta-Analyses of Randomised Controlled Trials: The QUOROM Statement. Onkologie. 2000;23:597–602.

Kuhry E, Schwenk WF, Gaupset R, Romild U, Bonjer HJ. Long-term results of laparoscopic colorectal cancer resection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 (2):CD003432

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12.

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–188.

Hosono S, Ohtani H, Arimoto Y, Kanamiya Y. Endoscopic stenting versus surgical gastroenterostomy for palliation of malignant gastroduodenal obstruction: a meta-analysis. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42:283–290.

Bonjer HJ, Hop WC, Nelson H, Sargent DJ, Lacy AM, Castells A, Guillou PJ, Thorpe H, Brown J, Delgado S, Kuhrij E, Haglind E, Påhlman L; Transatlantic Laparoscopically Assisted vs Open Colectomy Trials Study Group. Laparoscopically assisted vs open colectomy for colon cancer: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2007;142:298–303.

Leroy J, Jamali F, Forbes L, Smith M, Rubino F, Mutter D, Marescaux J. Laparoscopic total mesorectal excision (TME) for rectal cancer surgery: long-term outcomes. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:281–289.

Lee SI, Kim SH, Wang HM, Choi GS, Zheng MH, Fukunaga M, Kim JG, Law WL, Chen JB. Local recurrence after laparoscopic resection of T3 rectal cancer without preoperative chemoradiation and a risk group analysis: an Asian collaborative study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:933–938.

Ströhlein MA, Grützner KU, Jauch KW, Heiss MM. Comparison of laparoscopic vs. open access surgery in patients with rectal cancer: a prospective analysis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2008;51:385–91

Masui H, Ike H, Yamaguchi S, Oki S, Shimada H. Male sexual function after autonomic nerve-preserving operation for rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1140–1145.

Maas CP, Moriya Y, Steup WH, Kiebert GM, Kranenbarg WM, van de Velde CJ. Radical and nerve-preserving surgery for rectal cancer in The Netherlands: a prospective study on morbidity and functional outcome. Br J Surg. 1998;85:92–97.

Nesbakken A, Nygaard K, Bull-Njaa T, Carlsen E, Eri LM. Bladder and sexual dysfunction after mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2000;87:206–210.

Havenga K, Enker WE, McDermott K, Cohen AM, Minsky BD, Guillem J. Male and female sexual and urinary function after total mesorectal excision with autonomic nerve preservation for carcinoma of the rectum. J Am Coll Surg. 1996;182:495–502.

Liang JT, Lai HS, Lee PH. Laparoscopic pelvic autonomic nerve-preserving surgery for patients with lower rectal cancer after chemoradiation therapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1285–1287.

Asoglu O, Matlim T, Karanlik H, Atar M, Muslumanoglu M, Kapran Y, Igci A, Ozmen V, Kecer M, Parlak M. Impact of laparoscopic surgery on bladder and sexual function after total mesorectal excision for rectal cancer. Surg Endosc 2009;23:296–303.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ohtani, H., Tamamori, Y., Azuma, T. et al. A Meta-analysis of the Short- and Long-Term Results of Randomized Controlled Trials That Compared Laparoscopy-Assisted and Conventional Open Surgery for Rectal Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 15, 1375–1385 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-011-1547-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-011-1547-1