Abstract

Background

The application of laparoscopy-assisted gastric surgery has been increasing rapidly for the treatment of early gastric cancer. However, there were few reports of laparoscopic surgery in the management of advanced gastric cancer (AGC), especially with T3 depth of invasion. The aim of this study was to compare the technical feasibility and oncologic efficacy of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) versus open distal gastrectomy (ODG) for advanced gastric cancer.

Methods

A retrospective case–control study was performed comparing LADG and ODG for AGC. Thirty-five consecutive patients with AGC undergoing LADG between August 2005 and December 2007 were enrolled and these patients were compared with 35 AGC patients undergoing ODG during the same period.

Results

Forty-two (60.0%) patients were T3 in terms of depth of invasion. Tumor location and histology were similar between the two groups. Operation time was significantly longer in the LADG group than in the ODG group. Estimated blood loss was significantly less in the LADG group. Hospital length of stay after LADG was significantly shorter than in the open group. Postoperative pain was significantly lower for laparoscopic patients. There were no significant differences in postoperative early and late complication and in the number of lymph nodes retrieved between the two groups, and the cumulative survival of the two groups was similar.

Conclusion

Our data indicate that LADG for AGC, mostly with T3 depth of invasion, yields good oncologic outcomes including the similar early and late complication and the cumulative survival between the two groups after 50 months of follow-up. To be accepted as a choice treatment for advanced distal gastric cancer, well-designed prospective trial to assess long-term outcomes is necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Laparoscopic gastrectomy is revolutionizing surgery in the world, especially in the east for the high incidence of gastric cancer. Reports of laparoscopic techniques for treating patients with early gastric cancer in the world literatures have shown oncologic equivalency to the open technique, with the known benefits of minimally invasive approach, including less pain, earlier recovery, shorter hospital stay, and better quality of life.1–3 However, application of laparoscopic techniques for advanced gastric cancer (AGC) remains controversial because of the technical difficulty of extraperigastric lymphadenectomy, possibility of peritoneal or port site seeding of malignant cells, and insufficient data related to the procedure’s oncologic adequacy, especially for patients with T3 depth of invasion.4,5 Moreover, according to reports about laparoscopic surgery for AGC, the depth of invasion was mostly limited to T2 and T3 was rarely concerned.6,7

In the present study, we described our experience with laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy (LADG) in the treatment of AGC, most of which had T3 depth of invasion, and evaluated the oncologic safety of this approach through a case–control study.

Patients and Methods

From August 2005 to December 2007, we performed 364 gastrectomies for gastric cancer at our hospital. Of these patients, laparoscopy-assisted technique for D2 radical distal gastrectomy was carried out in 36 patients with AGC (9.6%). Surgical procedures were performed after obtaining informed consent following the explanation of the advantages, disadvantages, and any possible outcomes of LADG and open distal gastrectomy (ODG) in detail, and the surgical procedure (LADG or ODG) was chosen by the patients. Inclusion criteria were as follows: histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the stomach, performance status of ECOG 0-1, location of the tumor in the lower third of the stomach, no evidence of distant metastasis or invasion to adjacent organs, and confinement in the serosal layer (T3). We assessed the depth of invasion preoperatively by means of endoscopy and endoscopic ultrasonography and assessed the presence or absence of lymph node metastases using extracorporeal ultrasonography and computed tomography. One patient was excluded because of conversion to open gastrectomy due to T4 depth of invasion. Thus, 35 patients who underwent LADG were enrolled and compared with 35 patients who underwent open distal gastrectomy for AGC during the same period. We selected these controls from our computer database and matched them with the laparoscopic group for age, gender, and stage of gastric cancer. Follow-up data were obtained from patients’ office records, and computed tomography and endoscopy were performed every 6 months after surgery.

All patients were subjected to follow-up. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS.v16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). The statistical analysis was done using Student’s t test or chi-square test, and cumulative survival was compared by Kaplan–Meier method and log rank test. Values of p <0.05 were considered to indicate significance.

Surgical Procedures

The surgical approach was as follows: Patients in both the lower and middle thirds underwent distal gastrectomy with D2 dissection (Fig. 1),8 followed by Billroth II reconstruction. Patients were placed in the supine position and subjected to a 20° head-up tilt. After the establishment of a pneumoperitoneum at 12 mmHg, one initial 10-mm camera port was introduced below the umbilicus. The stomach and the peritoneal cavity were inspected to rule out adjacent organ invasion and peritoneal seeding using a 30° forward oblique laparoscope. A 10/12-mm port was inserted percutaneously in the left upper quadrant as a major hand port. A 5-mm trocar was placed at the contralateral site. Another two 5-mm trocars were respectively inserted in both the left and right lower quadrants.

The gastrocolic ligament was divided using an ultrasonically activated shear along the border of the transverse colon, thus including the greater omentum in the specimen to be resected. The dissection moved to the hepatic flexure and the pylorus. The right gastroepiploic vein was divided between titanium clips flush with the Henle’s trunk and ended up in the Fredet area, where group 14v was removed. Right gastroepiploic artery was vascularized and cut at its origin from the gastroduodenal artery with titanium clips, just above the pancreatic head, to dissect group 6. The stomach was lifted headward to expose the gastropancreatic fold. The left gastric vein was carefully prepared and separately divided at the upper border of pancreatic body and then the left gastric artery was vascularized to remove group 7. The lymph nodes along the proximal splenic artery (group 11p) were removed. Subsequently, the dissection was continued rightward along the artery to remove the nodes along the celiac axis and the common hepatic artery (group 9, 8a) by retraction on left artery. The left gastric artery was cut between titanium clips at its origin from the celiac axis. The right gastric artery was divided at its origin from the common hepatic artery to dissect group 5. Along the border of liver, the lesser omentum was dissected and the lymph nodes of the anterior region of the hepatoduodenal ligament (group 12a) were dissected and removed. The first part of the duodenum was dissected and then transected 2 cm below the pylorus with a 45-mm laparoscopic cartridge linear stapling device (endo-GIA, US Surgical Corporation, Norwalk, CT, USA) through a major hand port. The dissection of the gastrocolic ligament was continued toward the spleen with the removal of group 4sb; all short gastric vessels (group 4sa) were divided close to the spleen. Before gastric transection, the cardiac nodes were dissected en bloc including right cardiac nodes (group1) and left cardiac nodes (group 2). Two surgical instruments were used for such bit and precise dissection involved in ultrasonic devices (Ultracision–Harmonic Scalpel; Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH) and electrocautery. A small laparotomy incision was made under the xyphoid (5–7 cm). Gastrectomy and Billroth II anastomosis were extracorporeally performed using hand-sewn method. The specimen was pulled out of the peritoneal cavity through the small laparotomy incision.

For open procedure, approximately 15- to 20-cm length incision was made from falciform process to periumbilical area. Distal gastrectomy and D2 lymph node dissection were performed basically. Billroth II method was used for gastric reconstruction.

Results

Patient Demographics

Of the 70 case-matched patients evaluated, ten patients (14%) were women, with median age of 59 years. Median body mass index (BMI) for the laparoscopic group was 21 kg/m2 (range 18–30 kg/m2) compared with 23 kg/m2 (range 16–28 kg/m2) among the open surgery group. Patients from the laparoscopic group underwent a lower number of prior abdominal operations compared with the open group (14.3% versus 25.7%). All patients of the two groups did not undergo neoadjuvant chemotherapy (Table 1).

Operative Characteristics and Complications

The patients in both groups underwent distal gastrectomy with a Billroth II anastomosis. The median operative time was 320 min (range 260–570 min) for the laparoscopic procedure compared with 210 min (range 138–300 min) for the open procedure (p < 0.01). The median blood loss in the laparoscopic group was 200 ml (range 100–600 ml) compared with 300 ml (range 100–1,000 ml) in the open group (p < 0.05). The patient hospital length of stay after laparoscopic gastrectomy was 12 days (range 5–36 days) compared with 17 days (range 8–45 days, p < 0.01). Postoperative pain, as measured by number of days of IV narcotic use, was significantly lower for laparoscopic patients, with a median of 3.0 days (range 0–5 days) compared with 4.0 days (range 1–6 days) in the open group(p < 0.01, Table 2). No significant difference was observed between the two groups in the postoperative early complications (up to 30 days). Total early complications in the laparoscopic group were found in 2 of 35 patients, including wound infection (n = 1) and pancreatitis (n = 1). In the open group, complications occurred in 3 of 35 patients, including wound infection (n = 2) and wound dehiscence (n = 1). There were no late complications observed in the two groups.

Pathologic Characteristics

Pathology analyses were reviewed by a pathologist specializing in gastrointestinal diseases. Reports revealed no differences in histological type and tumor location among patients of both groups. Twenty-six patients of the laparoscopic group have tubular adenocarcinoma compared with 28 patients of the open group. In the laparoscopic group, the tumor locations of 21 and 14 patients were located in the body and antrum, respectively, compared with 22 and 13 patients in the open group. No positive resection margins were found in all of the resected specimens. The median number of lymph nodes resected following D2 dissection for laparoscopic surgery was 35 (range 7–63) compared with 38 (range 6–66) resected through open surgery (p = NS, Table 3). There was no significant difference between the two groups in depth of invasion, and 24.3%, 15.7%, and 60.0% of all the patients were T2A, T2B, T3, respectively (Table 4). There were no significant differences in extent of tumor invasion, pN stage, and TNM stage between the two groups. Twenty-eight patients (40.0%) were T2 (T2A or T2B) and 20 (60.0%) patients were T3. According to the International Union against Cancer (UICC) classification of gastric cancer,9 23 cases (32.9%) were at stage Ib, 23 cases (32.9%) at stage II, 16 cases (22.9%) at stage IIIa, and 8 cases (11.4%) at stage IIIb (Table 4).

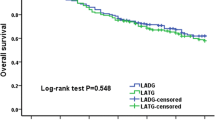

Median follow-up for the LADG group was 36.5 months (range 23–50 months) and for the ODG group was 38.5 months (range 27–50 months). There was no significant difference in the cumulative survival rate between the two groups after 50 months of follow-up (median follow-up of 35 months, p = 0.399; Fig. 2), and the cumulative survival of T2 and T3 in the LADG group was similar (p = 0.316, Fig. 3).

Discussion

Since Kitano et al. 10 performed the first laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy by a Billroth I reconstruction for a patient with gastric cancer, the use of laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer has been generally attempted in Japan and Korea, and the popularity of laparoscopic gastrectomy with lymph node dissection has increased rapidly.

For distal AGC, the Japanese Gastric Cancer Association has presented complete D2 lymphadenectomy including lymph nodes 11p, 12a, and 14v as the standard therapy. Nevertheless, laparoscopic D2 lymph node dissection has not been widely investigated since it is considered to be technically difficult and was performed only in a few institutes by highly experienced surgeons.11–14 Despite the ongoing controversy about whether laparoscopic gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer was safe and effective, the most recent clinical trials showed that laparoscopic D2 lymph node dissection was a safe procedure for advanced gastric cancer if the surgery was performed by experienced surgeons.11,15–17 Moreover, the most objective index of lymphadenectomy for gastric cancer is the comparison of the number of nodes obtained between open and laparoscopic surgery. According to the UICC TNM classification,9 surgical removal of at least 15 lymph nodes is advocated in gastric cancer. Many authors have reported no major difference between the LADG and ODG procedures in terms of the number of retrieved lymph nodes.12,18,19 We performed D2 lymph node dissection in both laparoscopic and open groups, and there was no significance between the two groups in the number of resected lymph nodes (median number 35 in the laparoscopic group versus 38 in the open group). This number is comparable to that reported by other authors who performed laparoscopic surgery for AGC.18,20,21

Although LADG has several advantages over conventional open surgery including less invasiveness, less pain, and earlier recovery, the question exists whether complications are prevalent with it. According to data from a nationwide questionnaire survey in Japan, the complication rate was 8.71% and the mortality rate was 0.083%.22 In the present study, the complication rate for all cases was 7.1% (5 in 70)—four of them were wound problems and one was mild pancreatitis—but these problems were resolved by conservative management. No patient died during hospitalization.

The majority of the studies about laparoscopic surgery for gastric cancer were focused on early gastric cancer, and only few reports have addressed the application of a laparoscopic procedure to patients with AGC and evaluate its safety in terms of clinicopathologic surgical outcomes and long-term follow-up results.6,13,17,20,23 Moreover, most of these reports mainly concerned cases with T2 or lower depth of invasion, and the number and proportion of T3 cases in these literatures were very small. Of the cases in the present study, 42 patients (60.0%) were diagnosed as having T3 gastric cancer. Though some surgeons thought that laparoscopic curative surgery for T3 AGC was not yet acceptable, for there could be peritoneal seeding of malignant cells in dealing with possible metastatic lymph nodes or gastric lesion or there could be a risk of port site recurrence,24 the results of the present study and other reports 7,19,20 showed good outcomes. There were few case–control studies on the outcome of LADG for AGC mainly with T2 and T3 depth of invasion published before. Strong et al.19 reported a case–control study about totally laparoscopic surgery for subtotal gastrectomy. They compared 30 patients undergoing laparoscopic gastrectomy with 30 matched open gastrectomy, and their results indicated technical feasibility and equivalent short-term recurrence-free survival of laparoscopic subtotal gastrectomy for gastric cancer when compared with open procedure. However, 33 patients (55%) in their study had early-stage disease (Ia/Ib).

Although the present study was not a randomized controlled study and the follow-up period was not long enough, the survival rate of patients with AGC who underwent LADG was shown to be good. In conclusion, this study showed that LADG for AGC has several advantages over ODG, and LADG yielded similar oncologic outcomes including early and late complication and cumulative survival after 50 months of follow-up. To be accepted as a choice treatment for advanced distal gastric cancer, well-designed prospective trial to assess long-term outcomes is necessary.

References

Hyung WJ, Cheong JH, Kim J, Chen J, Choi SH, Noh SH. Application of minimally invasive treatment for early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2004; 85:181–185; discussion 186.

Kim MC, Kim KH, Kim HH, Jung GJ. Comparison of laparoscopy-assisted by conventional open distal gastrectomy and extraperigastric lymph node dissection in early gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2005;91:90–94.

Kim YW, Baik YH, Yun YH, Nam BH, Kim DH, Choi IJ, Bae JM. Improved quality of life outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy for early gastric cancer: results of a prospective randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2008;248:721–727..

Hirabayashi Y, Yamaguchi K, Shiraishi N, Adachi Y, Saiki I, Kitano S. Port-site metastasis after CO2 pneumoperitoneum: role of adhesion molecules and prevention with antiadhesion molecules. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:1113–1117.

Memon MA, Khan S, Yunus RM, Barr R, Memon B. Meta-analysis of laparoscopic and open distal gastrectomy for gastric carcinoma. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1781–1789.

Lee JH, Kim YW, Ryu KW, Lee JR, Kim CG, Choi IJ, Kook MC, Nam BH, Bae JM. A phase-II clinical trial of laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3148–3153.

Lee J, Kim W. Long-term outcomes after laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: analysis of consecutive 106 experiences. J Surg Oncol. 2009;100:693–698.

Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese Classification of Gastric Carcinoma—2nd English Edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24.

Sobin LH, CW, editors. International Union Against Cancer (UICC) TNM classification of malignant tumors. 5th edition. New York: Wiley; 1997.

Kitano S, Iso Y, Moriyama M, Sugimachi K. Laparoscopy-assisted Billroth I gastrectomy. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1994;4:146–148.

Hur H, Jeon HM, Kim W. Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy for T2b advanced gastric cancers: three years’ experience. J Surg Oncol. 2008;98:515–519.

Kawamura H, Homma S, Yokota R, Yokota K, Watarai H, Hagiwara M, Sato M, Noguchi K, Ueki S, Kondo Y. Inspection of safety and accuracy of D2 lymph node dissection in laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy. World J Surg. 2008;32:2366–2370.

Tanimura S, Higashino M, Fukunaga Y, Takemura M, Tanaka Y, Fujiwara Y, Osugi H. Laparoscopic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: experience with more than 600 cases. Surg Endosc. 2008;22:1161–1164.

Bo T, Zhihong P, Peiwu Y, Feng Q, Ziqiang W, Yan S, Yongliang Z, Huaxin L. General complications following laparoscopic-assisted gastrectomy and analysis of techniques to manage them. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1860–1865.

Shinohara T, Kanaya S, Taniguchi K, Fujita T, Yanaga K, Uyama I. Laparoscopic total gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Arch Surg. 2009;144:1138–1142.

Du XH, Li R, Chen L, Shen D, Li SY, Guo Q. Laparoscopy-assisted D2 radical distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer: initial experience. Chin Med J (Engl). 2009;122:1404–1407.

Tokunaga M, Hiki N, Fukunaga T, Nohara K, Katayama H, Akashi Y, Ohyama S, Yamaguchi T. Laparoscopy-assisted distal gastrectomy with D2 lymph node dissection following standardization--a preliminary study. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1058–1063.

Hwang SI, Kim HO, Yoo CH, Shin JH, Son BH. Laparoscopic-assisted distal gastrectomy versus open distal gastrectomy for advanced gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1252–1258.

Strong VE, Devaud N, Allen PJ, Gonen M, Brennan MF, Coit D. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma: a case-control study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1507–1513.

Huscher CG, Mingoli A, Sgarzini G, Sansonetti A, Di Paola M, Recher A, Ponzano C. Laparoscopic versus open subtotal gastrectomy for distal gastric cancer: five-year results of a randomized prospective trial. Ann Surg. 2005;241:232–237.

Noshiro H, Nagai E, Shimizu S, Uchiyama A, Tanaka M. Laparoscopically assisted distal gastrectomy with standard radical lymph node dissection for gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1592–1596.

Japan Society for Endoscopic Surgery. The 8th questionnaire survey of endoscopic surgery. J Jpn Soc Endosc Sur. 2006;5:528–628.

Pugliese R, Maggioni D, Sansonna F, Ferrari GC, Forgione A, Costanzi A, Magistro C, Pauna J, Di Lernia S, Citterio D, Brambilla C. Outcomes and survival after laparoscopic gastrectomy for adenocarcinoma. Analysis on 65 patients operated on by conventional or robot-assisted minimal access procedures. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2009;35:281–288.

Lee YJ, Ha WS, Park ST, Choi SK, Hong SC. Port-site recurrence after laparoscopy-assisted gastrectomy: report of the first case. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007;17:455–457.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Shuang, J., Qi, S., Zheng, J. et al. A Case–Control Study of Laparoscopy-Assisted and Open Distal Gastrectomy for Advanced Gastric Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg 15, 57–62 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-010-1361-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-010-1361-1