Abstract

Introduction

Heller myotomy leads to good–excellent long-term results in 90% of patients with achalasia and thereby has evolved to the “first-line” therapy. Failure of surgical treatment, however, remains an urgent problem which has been discussed controversially recently.

Materials and Methods

A systematic review of the literature was performed to analyze the long-term results of failures after Heller’s operation with emphasis on treatment by remedial myotomy.

Discussion

Other reinterventions and their causes after failure of surgical treatment in patients with achalasia are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Achalasia is a rare motor disorder of the esophagus characterized by the loss of peristalsis and an inability of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) to relax—resulting in dysphagia, regurgitation, chest pain, and weight loss—the clinical hallmarks. As the etiology of achalasia still remains elusive, none of the current therapeutic options is able to the reverse the underlying neuropathology or associated impaired LES relaxation; thus, they remain strictly palliative. Targeting to reduce the LES resting pressure, all treatment modalities result in facilitating esophageal emptying by gravity—alleviating the symptoms associated with achalasia and preventing complications of retention. Results of prospective long-term investigations by Eckardt et al. showed that a postinterventional LES resting pressure of less than or equal to 10 mmHg was the most significant predictor of a favorable long-term remission.1,2 In 90% of patients with achalasia, good to excellent long-term results have been reported after Heller myotomy with antireflux plasty—using an open transabdominal or transthoracic or a laparoscopic or thoracoscopic approach.3–13 Minimally invasive surgery has influenced the treatment of achalasia more than any other gastrointestinal disorder. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy thereby has led to a significant change in the treatment algorithm of achalasia. Due to the high success rate of myotomy, it has been advocated as the “first line” therapy for achalasia, especially in younger patients <40 years.

Myotomy after failed pneumatic dilation has also proven significantly superior compared to patients with an “ideal” outcome in the course of only one dilatation.14

Thus, only one controlled trial has compared pneumatic dilation versus Heller myotomy, reporting 95% nearly complete symptom resolution in the surgical group and only 51% in the dilation group (p > 0.01) after 5 years.15 Results of a European prospective-randomized multicenter trial comparing laparoscopic myotomy with pneumatic dilation are about to be published.

The adequate myotomy should include 6–7 cm of the distal esophagus and be extended at least 2 cm on the gastric fundus, combined either with a 180° anterior (Dor) or a 270° posterior (Toupet) partial fundoplication. Data by Oelschlager et al. showed better clinical results when performing a Toupet fundoplication and an extended 3-cm myotomy on the gastric side than those obtained with a Dor fundoplication and a shorter 1.5-cm myotomy.16 However, it is difficult to interpret whether the improvements in outcomes were due to the sequential learning curve, the extension of the myotomy or the change in fundoplication.16

The operative procedure ought to be performed with careful attention to technical details to ensure completeness of the myotomy, to prevent later healing of the myotomy, and to avoid a too radical myotomy that might result in the development of gastroesophageal reflux (GER). Early operation before the progression of megaesophagus is recommended.

Through the reported high efficacy of Heller myotomy, it remains a matter of debate how to deal with failed surgery in patients with achalasia, which can be—according to the chronology of symptoms—divided into persistent and recurrent achalasia.

In detail, the following subgroups of failed surgical treatment for achalasia requiring reoperation can be identified:

-

1.

Persistent achalasia or early recurrence (incomplete myotomy, early fused or healed myotomy, early scarring or fibrosis)

-

2.

Failure of the co-combined antireflux procedure (hypercalibrated or floppy wrapping, “slipped fundoplication,” disruption of the wrap, paraesophageal hernia)

-

3.

GER

-

4.

Late recurrence of achalasia (late scarring or fibrosis, late fused or healed myotomy, progression to megaesophagus—with or without siphon formation)

-

5.

Progression to esophageal cancer (adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus following myotomy with GER, squamous cell carcinoma)

-

6.

Other (e.g., mucosal hernia, “diverticulization” of the mucosa, misdiagnosis at first operation, e.g., diffuse esophageal spasm, in which condition a routine myotomy is inadequate)

The aim was to analyze the long-term results of failures after Heller’s operation with emphasis on treatment by remedial myotomy and to discuss other reinterventions and their causes after failure of surgery in patients with achalasia.

Materials and Methods

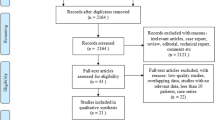

A systematic review of the literature was conducted including articles published in the English literature only and reflecting the time period from 1966 to August 31st, 2008. The search concentrated on the following databases and online catalogs: PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, and Current Contents Connect. Key terms searched for were “achalasia—treatment of surgical failure”, “remyotomy/re-do myotomy and achalasia,” “achalasia and relapse,” and “remedial/revisional surgery for achalasia”. Only series reporting on follow-up and focusing on long-term results after remedial myotomy following Heller’s operation were included in this analysis. Electronic searches identified 16 studies eligible for the above mentioned criteria.17–32

Results

Table 1 summarizes original articles reporting on persistent achalasia or early recurrence following open or minimally invasive Heller myotomy. With respect to articles of authors with multiple chronological series,18–21,23,24 only those ones with the largest number of patients (latest report) and/or the most detailed follow-up have been taken into account for this table.18,23

The largest series, reporting on 43 patients with repeated myotomy for a failed esophagomyotomy by Gayet and Fékété, followed up on their patients over a mean interval of 14 years after the last operation.23 Of the 43 patients described, n = 32 had inadequate primary myotomy, n = 3 interstitial sclerosis, n = 3 dolichomegaesophagus, n = 2 diffuse esophageal spasm (DES), and n = 3 secondary extended achalasia. Long-term results were “good” in 79%, “fair” in 9%, and a “poor” outcome in 12%. Reoperation in most cases was performed as a longer myotomy at the same site as the previous one or on the opposite side by a repeat laparotomy if a technical error was suspected. Only in patients in whom access to the esophagus was impeded by periesophageal sclerosis, a thoracotomy was opted for. Indications for a left transthoracic approach in this series were the confirmation by preoperative diagnostics that the initial myotomy had been performed correctly or if the myotomy needed to be extended in cases of DES. The transition from DES to achalasia with recurrent dysphagia has been described and requires reoperation with extension of the myotomy to include the LES.33

The second largest series presenting results of reoperative procedures for achalasia by Ellis at al. showed an “overall improvement” rate of 79%, including all other indications for reoperation (n = 66) in addition to remyotomy (such as antrectomy and Roux-Y diversion (n = 17), revision of fundoplication (n = 10), fundoplication (n = 5), esophagectomy (n = 5), and miscellaneous (n = 4)).18 In an earlier publication with a follow-up period of 1 month to 13 years (average, 5 years) after revisional myotomy, 12/18 patients (66.7%) revealed improved symptoms and the rate of poor results was rather high with 33.3%.19 Due to the relatively poor outcome following remyotomy or extension of a previously performed myotomy, they performed a discriminant analysis, including age, sex of patients, the interval between the original and the reoperation, as well as the cause of symptoms necessitating reoperation, which failed to disclose any predictors of good results.19

Publications on failure of laparoscopic myotomy and the need for reoperation include fewer patient numbers and shorter follow-up, if reported at all.26–28,30,32,34–36 One of the two largest series on laparoscopic reoperation reported on by Iqbal et al. comprised 11 patients with achalasia3 (others included had hypertensive lower esophageal sphincter and one had DES) and showed an overall symptom resolution of 40–89%.30 In this study, the interval between the first and the second operation was rather short with a mean of 23 (3–52) months and a mean follow-up of 30 months. Reasons for revisional myotomy were fibrosis (n = 4), incomplete myotomy (n = 5), and incomplete myotomy plus fibrosis (n = 3). In a recent study by Schuchert et al., seven out of 11 patients with redo-myotomy following minimally invasive myotomy were palliated successfully, whereas four out of 11 required subsequent esophagectomy.32 Laparoscopic redo procedures as published by Duffy,28 Gorecki,27 and Robinson26 exhibit similar good results in a rather short-term follow-up.

Discussion

Failures requiring postoperative treatment in patients with achalasia are reported with an incidence between 0% and 14% in open and minimally invasive series,19,23,37 although—probably due to the learning curve—the rate in latter series seems to be slightly higher. No data exist on the impact of pneumatic dilation and botulinum toxin injection prior to reoperation following myotomy on long-term outcomes. Although no prospective-randomized studies comparing pneumatic dilation, botulinum toxin injection, and remedial myotomy in patients with failure after Heller’s operation are available in the current literature, it is well accepted that—if a surgical–technical failure is assumed, as in most cases reported an incomplete or healed myotomy—the patient should be reoperated again. Comparisons of long-term results of reoperations after failure of Heller myotomy are made difficult due to a great variety of operative re-procedures, follow-up intervals, and the lack of standardized symptom scores as well as the incomplete use of objective measurements such as esophageal manometry, 24-h pH monitoring, and radiologic parameters. Although to be interpreted with caution due to the limited number of patients reported in the series of this review, a mixture of the results with other remedial procedures than remyotomy in some studies, different kinds of added antireflux procedure in revisional surgery and the type of objective assessment, the reported overall success rate is high—following open and minimally invasive remyotomy, and is liable to duplicate the good results of primary myotomy with respect to the symptomatic, radiologic, and manometric outcome.31

The best treatment for failed Heller myotomy is the prevention of failures. This can be achieved by routine use of intraoperative endoscopy to ensure that all muscle fibers have been separated properly, by an adequate length of the myotomy extending 2 to 3 cm on the gastric fundus, division of the short gastric vessels to perform a tension-free partial fundoplication—either according to Dor or Toupet—in order to prevent reflux and keep the edges of the myotomy wide open. Additional findings such as epiphrenic diverticulum or hiatal hernia should be repaired simultaneously. Diffuse esophageal spasm associated with achalasia requires extended myotomy best performed via a transthoracic route.

Persistent Achalasia or Early Recurrence

The most frequently reported reason for “early” reoperation in achalasia following Heller myotomy is inadequate myotomy (either upward or downward) or sclerosis and fibrosis of the myotomy fused or healed at an early stage. Incomplete myotomy on the gastric side as seen in Figs. 1 and 2 is often caused by the fear of producing mucosal injury, which typically occurs just below the esophagogastric junction, where the muscular layer diminishes. Failure to mobilize the underlying mucosa for one third to half of its circumference may lead to healing or early fusion of the myotomy resulting in persistent or early recurrent dysphagia. The impact of fibrosis—either as a primary finding or as a secondary development after myotomy—as well as postoperative sclerosis have not yet been fully understood and further prospective histopathologic studies of specimens taken at the first and the redo-operation should examine these aspects more closely. In contrast to these early postoperative phenomena, the development of a peptic stricture usually requires a much longer interval of months to years to occur. In the experience of Mercer and Hill, more than half of the reoperative procedures were necessitated by an incomplete or healed myotomy.17

a,b 49-year-old patient (♂) with two previous laparoscopic cardiomyotomies in an outside institution (2006 + 2007) and recurrent achalasia since 7/2007. Barium esophagogram (2/2008) revealed a relatively short narrow zone with diameter 3.8 mm at the esophagogastric junction. Remyotomy was performed 3/2008, and the previous myotomy was extended distally (+ Dor). The patient is completely free of symptoms ever since and gained 8 kg of weight since remedial (third) myotomy.

a,b 18-year-old patient (♂) with previous laparoscopic Heller myotomy in an outside institution (2006) and recurrent achalasia since 2007 with repeated unsuccessful pneumatic dilations postoperatively. Barium esophagogram (1/2008) showed a short narrow segment just above the cardia. Remyotomy was performed 3/2008, and muscle fibers cut at the previous site of the myotomy, which was extended 2.5 cm on the gastric cardia accomplished by Dor semifundoplication. The patient has a good swallowing function since remedial myotomy as well as weight gain, while dysphagia and regurgitation have been eliminated.

The finding of periesophageal sclerosis or fibrosis as a reason for fused or healed myotomy at an early stage might be related to imperfect hemostasis during the initial Heller’s operation.21,23 Diagnosis of interstitial esophageal sclerosis by radiologic or endoscopic examination is difficult, and in some cases, it can also be associated with esophagitis. Thus, the development of early scarring or fibrosis and re-fusion of the muscular edges of the myotomy has not been fully elucidated so far. Ellis and Olsen proposed that post-Heller scar formation complicates the course primarily through reapproximation of the cut edges of the distal musculature.38 In cases of revisional surgery, they found it “surprisingly difficult to identify the site of the previous myotomy.” In the series reported by Liu et al., periesophageal fibrosis was the second cause for reoperating after modified Heller esophagomyotomy alone or plus modified Belsey Mark IV antireflux procedure.39 Rosati et al. support limiting dissection in the parahiatal area and preserving the anatomical attachments of the region in order to prevent both postoperative reflux and fibrosis.12 Others contend that post-myotomy lateral submucosal dissection of the muscular edges reduces the incidence of fusion by further spreading of the cut muscular wall. Intraoperative mucosa perforation and consecutive repair has not been shown to be associated with a pathologic course influencing the final result.40

Even the event of scarring or fibrosis in patients with no previous surgery continues to be discussed controversially: smaller but significant amounts of spontaneous deep fibrosis have been reported in primary achalasia cases. Lendrum41 studied 13 patients with achalasia at autopsy and found no scarring in or around the narrow segment of the esophagus, but both Rake42 and MacCready43 stated that one of two autopsy cases revealed considerable fibrosis of the muscularis propria. Freeman44 emphasized the frequency of muscle atrophy in the vicinity of fibrosis between the two layers, although the usual interpretation is that such atrophy is merely a late response to esophageal retention, following a period of compensatory muscular hypertrophy.45,46 Goldblum et al.47 showed a secondary degeneration and fibrosis in 29/42 esophageal resectates with achalasia. Our own recent analyses of biopsies taken from the high pressure zone of the distal esophagus in patients undergoing surgery for achalasia revealed an association between the duration of symptoms prior to the operation and the degree of fibrosis.48 The crucial interpretational problem is whether intramuscular fibrosis can properly be considered part of the “retention esophagitis” that is rather frequently associated with untreated achalasia and often enough persists following Heller myotomy. Unfortunately, one can rarely find information on this matter in reports of surgical treatment of the disease. The amount of intramural fibrosis and periesophageal fibrosis added by the manipulation of Heller’s operation is less well known. In the paper by Steichen et al.,49 such fibrosis was considered a likely sequel to the operation unless precluded by gentle technique: post-Heller recurrences were “due mainly to periesophageal scarring and constriction, secondary to dissection in that region.”

Alternatively to remedial Heller myotomy after failure of surgery, Guarner and Gavino proposed the modified Heyrowsky operation associated with fundoplication, especially in patients with repeated unsuccessful myotomies.50 This procedure, including a latero-lateral anastomosis performed between the gastric fundus and the dilated lower segment of the esophagus, had been discarded almost immediately after its introduction in 1913 because of the severe reflux it had produced.51 In combination with a 360° fundoplication covering the anastomosis in six patients, five of whom had undergone multiple previous cardiomyotomies, the long-term results of Guarner and Gavino showed no gastroesophageal reflux in any patient, and only one patient developed infrequent dysphagia.50

Failure of the Co-Combined Antireflux Procedure

A major controversy relates to the type of fundoplication added to the myotomy associated with unsuccessful outcome after myotomy. Common failures of myotomy associated to the co-combined antireflux procedure are hypercalibrated or floppy wrapping, “slipped fundoplication,” disruption of the wrap, and development of paraesophageal hernia.

To perform or not to perform an antireflux procedure along with myotomy at all has been a matter of debate for a long time, and a metaanalysis failed to demonstrate a significant difference between wrapped and nonwrapped patients.52 Ellis, the pioneer of the transthoracic approach, advocated a limited (<1 cm) gastric myotomy without an antireflux procedure53 and in contrast to the previously reported low reoperation rate of 2.9% in patients with Heller’s operation19 at a very late follow-up, symptomatic improvement markedly deteriorated in the course of time with this approach, and the rate of excellent results progressively decreased from 54% at 10 years to 32% at 20 years.54

Nissen fundoplication may ultimatively lead to dysphagia, and a partial fundoplication is usually recommended in association with myotomy. Advocates of the Dor semifundoplication argue that the procedure is easier than a Toupet antireflux plasty, as the posterior esophageal attachments and the short gastric vessels may be kept untouched. Furthermore, it may protect against potential intraoperative unrecognized mucosal leaks. On the other side, authors advocating the Toupet procedure argue with the benefit of providing a better antireflux barrier and of keeping the edges of the myotomy distracted, in order to prevent postoperative recurrent dysphagia that may result from healing or refusion of the myotomy borders. The “ideal” added antireflux plasty to esophagomyotomy and the associated induction of additional scar/fibrosis formation is a matter of ongoing discussion and a prospective-randomized study is desirable for further clarification.

GER

Complications of Heller myotomy may also develop, when it is carried too far distally. Jara et al. have correlated the incidence of gastroesophageal reflux with the length of the myotomy performed on the stomach: if it was longer than 2 cm, reflux was always present postoperatively.55

The gastroesophageal junction becomes incompetent, and reflux occurs. Due to disordered or absent motility in the body of the esophagus in achalasia, prolonged contact of acid with the esophageal mucosa causes severe esophagitis.

Overzealous hiatal dissection, resulting in an iatrogenic hiatal hernia may also cause reflux esophagitis. To avoid this situation, the myotomy should be performed without mobilizing the gastroesophageal junction. If the phrenoesophageal bundles are damaged during surgery, the gastroesophageal junction and/or the concomitant semifundoplication is free to migrate into the mediastinum. The latter will cause a paraesophageal hernia or “slipped fundoplication.”

Gastroesophageal reflux deteriorates outcomes of Heller myotomy in the course of time and was the most frequent cause of failure with a reported incidence of 20.9% in very long-term follow-up after a mean of 190 months as reported by Csendes et al.56

Most patients can be successfully treated conservatively with proton pump inhibitor medication. However, development of peptic stricture in this setting is a major therapeutic challenge and surgical reinterventions are frequently required. Antrectomy and Roux-en-Y diversion for severe postoperative GER, frequently with resection of stricture, was the next most common operation in 25.8% of 66 reoperative procedures for failure after esophagomyotomy (with remyotomy being the most frequent) in a series reported by Ellis et al.18 Picchio et al.57 achieved good long-term results in 85% of 21 operated patients with jejunal interposition for peptic stenosis of the esophagus following esophagomyotomy for achalasia. Reflux esophagitis secondary to myotomy was the most common cause in 21 out of 37 patients with esophagogastric resection after Heller’s myotomy as described by Gayet and Fékété.23

Late Recurrence of Achalasia and Progression to Megaesophagus

The cause of late scarring or fibrosis, late fused, or healed myotomy—especially with regard to histopathological examinations—has not been fully understood. Re-fibrosis can be secondary to external fibrotic tissue that involves the myotomy site or internal fibrosis from gastroesophageal reflux. As GERD is often associated with a peptic (internal) stricture and will develop in the late course of myotomy, it can be easily differentiated from external fibrosis, which usually occurs in the medium follow-up after the original operation for achalasia. The transition from early scarring and early fibrosis seems to be fluently and can be, similar to the chronologically early variant, associated to surgical manipulation, bleeding, extensive paraesophageal scar, and adhesion formation. The type of (semi-)fundoplication added to the myotomy has been reported to affect the incidence of fibrosis significantly in the long run.

Patients requiring reoperation after cardiomyotomy in the form of esophagectomy—due to irreversible progression of the disease and development of megaesophagus, are usually older and have a longer duration of the disease and a longer interval between the first and the redo operation as compared to patients with remyotomy for failure of Heller’s operation.31 Although the functional results after primary myotomy in patients with a dilated sigmoid-shaped megaesophagus continue to be discussed controversially in the literature,58,59 general consensus exists regarding the surgical procedure for advanced megaesophagus with or without siphon formation after prior myotomy. Resections of the esophagus as a result of a dolichomegaesophagus are described in the literature with a frequency of 8% to 9% in relation to the total number of treated achalasia patients,19,60 whereas this frequency in patients with Chagas disease is markedly higher (14%).61

The resection and reconstruction of megaesophagus following myotomy in the long-term course lead to a marked functional improvement with elimination of dysphagia. These decompensated end stages of achalasia are usually irreversible and cannot be improved by conservative or nonresecting surgical procedures. The choice of the operative approach and the type of interposition are strongly determined by the type of previous surgery. Esophagectomy—open62–66 or minimally invasive32,67–69—with gastric pull-up or colon interposition is the preferred procedure and can be performed with low morbidity, leading to symptomatic relief and restoration of alimentation and quality of life.

Progression to Esophageal Cancer

It is questionable if progression to esophageal cancer following Heller myotomy (adenocarcinoma in Barrett’s esophagus or squamous cell carcinoma) is a failure of surgery or a failure of follow-up. Since the original report by Fagge in 1872,70 the risk of developing esophageal squamous cell carcinoma in patients with long-standing achalasia has been estimated to occur from 1% up to 33% of patients.71–75 Streitz et al. reported a prevalence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma of 3.7%, a risk that was found to be 14.5 times greater than an age- and sex-adjusted control group.74 Development of adenocarcinoma after myotomy in the sequelae of Barrett’s esophagus might be due to a too long myotomy and only few case reports on this association are available.76,77

Comment

Remyotomy is of high efficacy in patients with failure after Heller’s operation. However, the best treatment for patients with achalasia should be to prevent symptom recurrence by adequate primary therapy. Intraoperative endoscopy is valuable to control the completeness and proper length of the myotomy. When symptoms—especially dysphagia—do persist or recur after a short interval following Heller myotomy, intensive examinations, namely barium esophagogram, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, functional testing with esophageal manometry, and—in cases with suspected development of gastroesophageal reflux—24-h pH monitoring are mandatory to determine the cause of failure exactly. Individualized remedial surgery is required to correct the problem. Further prospective-randomized studies should focus on comparing—in patients with similar diameters of the esophagus and presurgical treatment—the length of the myotomy, the type of added antireflux procedure and histopathologic/immunohistochemic findings with regard to scarring in untreated and repeatedly myotomized patients. Laparoscopic revision for failed Heller myotomy is feasible with low morbidity and results are encouraging. Reoperation for achalasia may require esophagectomy to relieve symptoms if other measures fail.

References

Eckardt VF, Aignherr C, Bernhard G. Predictors of outcome in patients with achalasia treated by pneumatic dilation. Gastroenterology 1992;103:1732–1738.

Eckardt VF, Gockel I, Bernhard G. Pneumatic dilation for achalasia: late results of a prospective follow-up investigation. Gut 2004;53:629–622. doi:10.1136/gut.2003.029298.

Gockel I, Junginger T, Eckardt VF. Long-term results of conventional Heller-myotomy in patients with achalasia: a prospective 20-year analysis. J Gastrointest Surg 2006;10:1400–1408. doi:10.1016/j.gassur.2006.07.006.

Costantini M, Zaninotto G, Guirroli E, Rizzetto C, Portale G, Ruol A, Nicoletti L, Ancona E. The laparoscopic Heller-Dor operation remains an effective treatment for esophageal achalasia at a minimum 6-year follow-up. Surg Endosc 2005;19:345–351. doi:10.1007/s00464-004-8941-7.

Moreno Gonzales E, Garcia Alvares A, Landa Garcia I, Gutierrez M, Rico Selas P, Garcia Garcia I, Jover Navalon JM, Ari Diaz J. Results of surgical treatment of esophageal achalasia. Multicenter retrospective study of 1856 cases. Int Surg 1988;73:69–77.

Csendes A, Braghetto I, Mascaro J, Henriquez A. Late subjective and objective evaluation of the results of esophagomyotomy in 100 patients with achalasia of the esophagus. Surgery 1988;104:469–475.

Desa LA, Spencer J, McPherson S. Surgery for achalasia cardiae: the Dor operation. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 1990;72:128–131.

Bonavina L, Nosadini A, Bardini R, Baessato M, Peracchia A. Primary treatment of esophageal achalasia. Long-term results of myotomy and Dor fundoplication. Arch Surg 1992;127:222–227.

Picciocchi A, Cardillo G, D’Ugo D, Castrucci G, Mascellari L, Granone P. Surgical treatment of achalasia: a retrospective comparative study. Surg Today 1993;23:855–859. doi:10.1007/BF00311361.

Mattioli S, Di Simone MP, Bassi F, Pilotti V, Felice V, Pastina M, Lazzari A, Gozzetti G. Surgery for esophageal achalasia. Long-term results with three different techniques. Hepatogastroenterology 1996;43:492–500.

Graham AJ, Finley RJ, Worsley DF, Dong SR, Clifton JC, Storseth C. Laparoscopic esophageal myotomy and anterior partial fundoplication for the treatment of achalasia. Ann Thorac Surg 1997;64:785–789. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(97)00628-0.

Rosati R, Fumagalli U, Bona S, Bonavina L, Pagani M, Peracchia A. Evaluating results of laparoscopic surgery for esophageal achalasia. Surg Endosc 1998;12:270–273. doi:10.1007/s004649900649.

Patti MG, Fisichella PM, Perretta S, Galvani C, Gorodner MV, Robinson T, Way LW. Impact of minimally invasive surgery on the treatment of esophageal achalasia: a decade of change. J Am Coll Surg 2003;196:698–703. doi:10.1016/S1072-7515(02)01837-9.

Gockel I, Junginger T, Bernhard G, Eckardt VF. Heller myotomy for failed pneumatic dilation in achalasia: How effective is it. Ann Surg 2004;239:371–377. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000114228.34809.01.

Csendes A, Braghetto I, Henriquez A, Cortes C. Late results of a prospective randomised study comparing forceful dilatation and oesophagomyotomy in patients with achalasia. Gut 1989;30:299–304. doi:10.1136/gut.30.3.299.

Oelschlager BK, Chang L, Pellegrini CA. Improved outcomes after extended gastric myotomy for achalasia. Arch Surg 2003;138:490–497. doi:10.1001/archsurg.138.5.490.

Mercer CD, Hill LD. Reoperation after failed esophagomyotomy for achalasia. Can J Surg 1986;29:177–180.

Ellis FH Jr. Failure after esophagomyotomy for esophageal motor disorders. Causes, prevention, and management. Chest Clin N Am 1997;7:477–488.

Ellis FH Jr, Crozier RE, Gibb SP. Reoperative achalasia surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1986;92:859–865.

Ellis FH Jr, Gibb SP. Reoperation after esophagomyotomy for achalasia of the esophagus. Am J Surg 1975;129:407–412. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(75)90185-3.

Patrick DL, Payne WS, Olsen AM, Ellis FH Jr. Reoperation for achalasia of the esophagus. Arch Surg 1971;103:122–1228.

Nelems JM, Cooper JD, Pearson FG. Treatment of achalasia: esophagomyotomy with antireflux procedure. Can J Surg 1980;23:588–589.

Gayet B, Fékété F. Surgical management of failed esophagomyotomy (Heller’s operation). Hepatogastroenterol 1991;38:488–492.

Fékété F, Breil P, Tossen JC. Reoperation after Heller’s operation for achalasia and other motility disorders of the esophagus: a study of eighty-one reoperations. Int Surg 1982;67:103–110.

Bove A, Corbellini L, Catania A, Chiarini S, Bongarzoni G, Stella S, De Antoni E, De Matteo G. Surgical controversies in the treatment of recurrent achalasia of the esophagus. Hepatogastroenterol 2001;48:715–717.

Robinson TN, Galvani CA, Dutta SK, Gorodner MV, Patti MG. Laparoscopic treatment of recurrent dysphagia following transthoracic myotomy for achalasia. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2003;13:401–403. doi:10.1089/109264203322656487.

Gorecki PJ, Hinder RA, Libbey JS, Bammer T, Floch N. Redo laparoscopic surgery for achalasia: Is it feasible. Surg Endosc 2002;16:772–776. doi:10.1007/s00464-001-8178-7.

Duffy PE, Awad ZT, Filipi CJ. The laparoscopic reoperation of failed Heller myotomy. Surg Endosc 2993;17:1046–1049.

Kiss J, Vörös A, Szirányi E, Altorjay A, Bohák A. Management of failed Heller’s operations. Surg Today 1996;26:541–545. doi:10.1007/BF00311564.

Iqbal A, Tierney B, Haider M, Salinas VK, Karu A, Turaga KK, Mittal SK, Filipi CJ. Laparoscopic reoperation for failed Heller myotomy. Dis Esophagus 2006;19:193–199. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2050.2006.00564.x.

Gockel I, Junginger T, Eckardt VF. Persistent and recurrent achalasia after Heller myotomy. Analysis of different patterns and long-term results of reoperation. Arch Surg 2007;142:1093–1097. doi:10.1001/archsurg.142.11.1093.

Schuchert MJ, Luketich JD, Landreneau RJ, Kilic A, Gooding WE, Alvelo-Rivera M, Christie NA, Gilbert S, Pennathur A. Minimally-invasive esophagomyotomy in 200 consecutive patients: factors influencing postoperative outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1729–1734. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.11.017.

Vantrappen G, Janssens J, Hellemans J, Coremans G. Achalasia, diffuse esophageal spasm, and related motility disorders. Gastroenterology 1979;76:450–457.

Patti MG, Molena D, Fisichella PM, Whang K, Yamada H, Perretta S, Way LW. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy and Dor fundoplication for achalasia. Analysis of successes and failures. Arch Surg 2001;136:870–877. doi:10.1001/archsurg.136.8.870.

Patti MG, Pellegrini CA, Horgan S, Arcerito M, Omelanczuk P, Tamburini A, Diener U, Eubanks TR, Way LW. Minimally invasive surgery for achalasia. An 8-year experience with 168 patients. Ann Surg 1999;230:587–594. doi:10.1097/00000658-199910000-00014.

Zaninotto G, Costantini M, Portale G, Battaglia G, Molena D, Carta A, Costantino M, Nicoletti L, Ancona E. Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of failures after laparoscopic Heller myotomy for achalasia. Ann Surg 2002;235:186–192. doi:10.1097/00000658-200202000-00005.

Perrone JM, Frisella MM, Desai KM, Soper NJ. Results of laparoscopic Heller-Toupet operation for achalasia. Surg Endosc 2004;18:1565–1571.

Ellis FH Jr, Olsen AM. Achalasia of the Esophagus. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders Co., 1969, p 215.

Liu HC, Huang BS, Hsu WH, Huang CJ, Hou SH, Huang MH. Surgery for achalasia: long-term results in operated achalasic patients. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;4:312–320.

Costantini M, Rizzetto C, Zanatta L, Finotti E, Amico A, Nicoletti L, Guirroli E, Zaninotto G, Ancona E. Accidental mucosal perforation during laparoscopic Heller-Dor myotomy does not effect the final outcome of the operation (2008) SSAT abstract M1530, Digestive Disease Week, May 18–21, San Diego

Lendrum FC. Anatomic features of the cardiac orifice of the stomach with special reference to cardiospasm. Arch Intern Med 1937;59:474–511.

Rake GW. On the pathology of achalasia of the cardia. Guys Hosp Rep 1927;77:141–150.

MacCready PB. Cardiospasm: report of two cases with post-mortem observations. Arch Otolaryng 1935;633–647.

Freeman EB. Chronic cardiospasm: report of fatal case with pathological findings. South Med J 1933;26:71–76.

Beattie WJH. Achalasia of the cardia with a report on ten cases. St Bart Hosp Rep 1931;64:39–84.

Walton AJ. The surgical treatment of cardiospasm. Br J Surg 1925;12:701–737. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800124807.

Goldblum JR, Whyte RI, Orringer MB, Appelman HD. Achalasia. A morphologic study of 42 resected specimens. Am J Surg Pathol 1994;18:327–337.

Gockel I, Bohl JR, Doostkam S, Eckardt VF, Junginger T. Spectrum of histopathologic findings in patients with achalasia reflects different etiologies. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;21:727–733. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04250.x.

Steichen FM, Heller E, Ravitch MM. Achalasia of the esophagus. Surgery 1960;47:846–876.

Guarner V, Gavino J. The Heyrowsky operation associated with fundoplication for the treatment of patients with achalasia of the esophagus after failure of the cardiomyotomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1983;157:450–454.

Heyrowsky H. Casuistik und Therapie der idiopathischen Dilatation der Speiseröhre, Oesophagogastroanastomose. Arch Chir 1913;100:703–715.

Lyass S, Thoman D, Steiner JP, Phillips E. Current status of an antireflux procedure in laparoscopic Heller myotomy. Surg Endosc 2003;17:554–558. doi:10.1007/s00464-002-8604-5.

Ellis FH Jr, Crozier RE, Watkins E Jr. Operation for esophageal achalasia. Results of esophagomyotomy without an antireflux operation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1984;88:344–351.

Ellis FH Jr. Oesophagomyotomy for achalasia: a 22-year experience. Br J Surg 1993;80:882–885. doi:10.1002/bjs.1800800727.

Jara FM, Toledo-Pereyra LH, Lewis JW, Magilligan DJ. Long term results of esophagomyotomy for achalasia of the esophagus. Arch Surg 1979;114:935–936.

Csendes A, Braghetto I, Burdiles P, Korn O, Csendes P, Henríquez A. Very late results of esophagomyotomy for patients with achalasia. Clinical, endoscopic, histologic, manometric and acid reflux studies in 67 patients for a mean follow-up of 190 months. Ann Surg 2006;243:196–203. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000197469.12632.e0.

Picchio M, Lombardi A, Zolovkins A, Della Casa U, Paolini A, Fegiz G, Mihelson M. Jejunal interposition for peptic stenosis of the esophagus following esophagomyotomy for achalasia. Int Surg 1997;82:198–200.

Pechlivanides G, Chrysos E, Athanasakis E, Tsiaoussis J, Vassilakis JS, Xynos E. Laparoscopic Heller cardiomyotomy and Dor fundoplication for esophageal achalasia. Arch Surg 2001;136:1240–3. doi:10.1001/archsurg.136.11.1240.

Patti MG, Feo CV, Diener U, Tamburini A, Arcerito M, Safadi B, Way LW. Laparoscopic Heller myotomy relieves dysphagia in achalasia when the esophagus is dilated. Surg Endosc 1999;13:843–847. doi:10.1007/s004649901117.

Miller DL, Allen MS, Trastek VF, Deschamps C, Pairolero PC. Esophageal resection for recurrent achalasia. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60:922–925. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(95)00522-M.

Pinotti HW, Cecconello I, da Rocha JM, Zilberstein B. Resection for achalasia of the esophagus. Hepatogastroenterology 1991;38:470–473.

Orringer MB, Marshall B, Stirling MC. Transhiatal esophagectomy for benign and malignant disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1993;105:265–277.

Deveney EJ, Lannettoni MD, Orringer MB, Marshall B. Esophagectomy for achalasia: patient selection and clinical experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:854–858. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(01)02890-9.

Peters JH, Kauer WK, Crookes PF, Ireland AP, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR. Esophageal resection with colon interposition for end-stage achalasia. Arch Surg 1995;130:632–637.

Watson TJ, DeMeester TR, Kauer WK, Peters JH, Hagen JA. Esophageal replacement for end-stage benign esophageal disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1998;115:1241–1249. doi:10.1016/S0022-5223(98)70205-3.

Glatz SM, Richardson JD. Esophagectomy for end stage achalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 2007;11:1134–1137. doi:10.1007/s11605-007-0226-8.

Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Jategaonkar PA, Maheshkumaar GS, Anand NV. Laparoscopic transhiatal esophagectomy for “sigmoid” megaesophagus following failed cardiomyotomy: Experience of 11 patients. Dig Dis Sci 2008;53:1513–1518. doi:10.1007/s10620-007-0050-8.

Luketich JD, Nguyen NT, Weigel T, Ferson P, Keenan R, Schauer P. Minimally invasive approach to esophagectomy. JSLS 1998;2:243–247.

Luketich JD, Fernando HC, Christie NA, Buenaventura PO, Keenan RJ, Ikramuddin S, Schauer PR. Outcomes after minimally invasive esophagomyotomy. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72:1909–1912. doi:10.1016/S0003-4975(01)03127-7.

Fagge CH. A case of simple stenosis of the esophagus, followed by epithelioma. Guys Hosp Rep 1872;17:413–415.

Aggestrup S, Holm JC, Sorensen HR. Does achalasia predispose to cancer of the esophagus. Chest 1992;102:1013–1016. doi:10.1378/chest.102.4.1013.

Meijssen MAC, Tilanus HW, van Blankenstein M, Hop WC, Ong GL. Achalasia complicated by oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective study in 195 patients. Gut 1992;33:155–158. doi:10.1136/gut.33.2.155.

Peracchia A, Segalin A, Bardini R, Ruol A, Bonavina L, Baessato M. Esophageal carcinoma and achalasia: prevalence, incidence and results of treatment. Hepatogastroenterology 1991;130:514–516.

Streitz JM, Ellis FH, Gibb SP, Heatley GM. Achalasia and squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: analysis of 241 patients. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;59:1604–1609. doi:10.1016/0003-4975(94)00997-L.

Brücher BL, Stein HJ, Bartels H, Feussner H, Siewert JR. Achalasia and esophageal cancer: incidence, prevalence, and prognosis. World J Surg 2001;25:745–749. doi:10.1007/s00268-001-0026-3.

Ruffato A, Mattioli S, Lugaresi ML, D’Ovidio F, Antonacci F, Di Simone MP. Long-term results after Heller-Dor operation for oesophageal achalasia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2006;29:914–919. doi:10.1016/j.ejcts.2006.03.044.

Gaissert HA, Lin N, Wain JC, Fankhauser G, Wright CD, Mathisen DJ. Transthoracic Heller myotomy for esophageal achalasia: analysis of long-term results. Ann Thorac Surg 2006;81:2044–2049. doi:10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.01.039.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gockel, I., Timm, S., Sgourakis, G.G. et al. Achalasia—If Surgical Treatment Fails: Analysis of Remedial Surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 14 (Suppl 1), 46–57 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-009-1018-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-009-1018-0