Abstract

Background

Secondary achalasia or pseudoachalasia is a clinical presentation undistinguishable from achalasia in terms of symptoms, manometric, and radiographic findings, but associated with different and identifiable underlying causes.

Methods

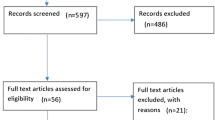

A literature review was conducted on the PubMed database restricting results to the English language. Key terms used were “achalasia-like” with 63 results, “secondary achalasia” with 69 results, and “pseudoachalasia” with 141 results. References of the retrieved papers were also manually reviewed.

Results

Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment were reviewed.

Conclusions

Pseudoachalasia is a rare disease. Most available evidence regarding this condition is based on case reports or small retrospective series. There are different causes but all culminating in outflow obstruction. Clinical presentation and image and functional tests overlap with primary achalasia or are inaccurate, thus the identification of secondary achalasia can be delayed. Inadequate diagnosis leads to futile therapies and could worsen prognosis, especially in neoplastic disease. Routine screening is not justifiable; good clinical judgment still remains the best tool. Therapy should be aimed at etiology. Even though Heller’s myotomy brings the best results in non-malignant cases, good clinical judgment still remains the best tool as well.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The modern concept of achalasia, and this term as a matter of fact, is credited to Lendrum [1] when associated the disease to an incomplete relaxation of the lower esophageal (LES) sphincter (LES) in 1937. Chicago Classification in its 4.0 version in 2021 [2], the most accepted classification for esophageal motility disorders based on high-resolution manometry, defines achalasia by an abnormal relaxation of the LES, as defined manometrically as an elevated median integrated relaxation pressure and total failed peristalsis. The Classification also categorized achalasia into three different subtypes based on esophageal pressurization during swallows: Type I is characterized by no pressurization, Type II by panesophageal pressurization occurring in ≥ 20% swallows, and Type III by premature/spastic contractions in ≥ 20% swallows.

Primary achalasia is understood as an idiopathic disease with loss of esophageal myenteric ganglia [3, 4]. Some patients, however, develop a clinical presentation undistinguishable from achalasia in terms of symptoms, manometric, and radiographic findings, but associated with identifiable underlying causes. This condition is known as secondary achalasia or pseudoachalasia, first described by Olgivie in 1947 [5]. Different etiologies for pseudoachalasia were described: neoplastic (mainly cardia cancer, but also malignant mesothelioma, breast cancer, sarcoma, and other tumors) [5,6,7,8,9], post-Nissen fundoplication [10], bariatric surgery [4, 11, 12], amyloidosis [13], etc.

Very interestingly, the interest in pseudoachalasia oscillated along time. Initial studies were numerous with a high concern for the disease, then for some time, this theme was left aside, but with the ascension of bariatric surgery, pseudoachalasia returned to the focus of studies again to decrease once more after changes in the trends for bariatric techniques. This pendulum of interest brought some insights into the pathophysiology and treatment of pseudoachalasia.

Methods

A literature review was conducted on the PubMed database restricting results to the English language. Key terms used were “achalasia-like” with 63 results, “secondary achalasia” with 69 results, and “pseudoachalasia” with 141 results. References of the retrieved papers were also manually reviewed.

Etiology

More than 25 different causes for pseudoachalasia have been described [14, 15]. Most causes are linked to esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction or neuronal damage. In achalasia series, pseudoachalasia comprises 1.5–5% of all cases [16,17,18].

Neoplastic obstruction

Tumors at the cardia were the first and most described causes for pseudoachalasia [16, 17]. It is the most common cause in compilations of literature series, comprising 70% of the cases, with a preponderance of cardia cancer in 50% and other malignancies in 20% [16]. It is virtually impossible to estimate the number of patients with a tumor that presents with pseudoachalasia since esophageal manometry and barium swallow will not be part of the workup of these individuals and symptoms overlap.

Tumoral invasion, intrinsic or extrinsic, could limit esophagogastric junction outflow, leading to peristalsis deterioration. A tumor may also invade the esophageal submucosa and destroy the esophageal myenteric plexus precluding adequate LES relaxation [14, 15].

Paraneoplastic syndrome

Cancer may lead to pseudoachalasia beyond the mechanical hypotheses. Paraneoplastic syndrome may encompass secondary achalasia. Pathophysiology is linked to the release by the tumor of neurotoxic substances [19], antibodies, or myenteric plexus infiltration by lymphocytes and plasma cells leading to neuronal degeneration [20].

The most common tumors associated with pseudoachalasia are small-cell lung carcinoma; however, other neoplasms are also associated, such as anaplastic lung adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, and ovarian papillary serous adenocarcinoma [18, 20,21,22].

Postoperative

Pseudoachalasia has been described after different operations at the cardia or proximal stomach. It may be diagnosed very precociously [23], with an average of 4 months after the index operation [24], or very late [25] although one may question if very later an idiopathic achalasia developed independent of the operation—metachronous primary achalasia [24]. It must be emphasized that some authors described a reversible esophageal ileus following antireflux surgery with 50% of aperistalsis on a postoperative day 1 [26]. Thus, diagnosis of pseudoachalasia very early or very late in evolution must be cautiously done.

Pseudoachalasia may occur in about 3% of the cases after a Nissen fundoplication [24]. One case after magnetic ring sphincter augmentation has been reported [27]. Adjustable gastric banding, fortunately falling into disuse, is an operation with a high risk of postoperative pseudoachalasia [28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35]. Pseudoachalasia is rare after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy [36]. Again, the incidence of pseudoachalasia post-bariatric surgery may be lower than reported since cases may correspond to classic achalasia as esophageal manometry is not recommended in the preoperative work-up of these patients [37], and achalasia in the morbidly obese population may be asymptomatic [38, 39].

One hypothesis proposed for pathophysiology is vagal nerve injury during the operation with LES denervation [24]. There are, however, strong arguments against this proposal. First, there are some case reports [40,41,42], but pseudoachalasia is rare following surgical vagotomy, an operation extensively performed during peptic ulcer surgery. Also, periesophageal fibrosis cannot be excluded as a cause since there are cases after highly selective vagotomy that excludes cardiac denervation [43]. Moreover, vagal damage is more common after reoperations at the esophagogastric junction [44] and paraesophageal hernia repair [45], but we could not find cases reported after these operations.

Another hypothesis proposed for pathophysiology is chronic outflow obstruction. Experiments in cats show an achalasia-like motility pattern when the distal esophagus of cats is partially obstructed by a band [46, 47]. A mechanical obstruction or anatomic failure of the fundoplication, however, cannot be demonstrated in most cases of post-Nissen pseudoachalasia [24]. We can parallel this finding with a series of conversion from total to partial fundoplication. Most of the patients in these series do not have a mechanical obstruction or anatomic failure and are unresponsive to endoscopic dilatation [27, 48]. Total fundoplication is probably just an obstacle to the esophageal peristalsis in this small percentage of individuals. Very interestingly, we could not find cases reported after a partial fundoplication.

Parallel with achalasia

Pseudoachalasia may give some insights into achalasia pathophysiology and vice versa. Traditionally, the combination of LES dysfunctional relaxation and aperistalsis guided the diagnosis. Advances in esophageal manometry improved the understanding and classification of achalasia. New variants of achalasia were proposed, with incidences that are not insignificant [2, 49]. These variants question the all or nothing at all concept for aperistalsis but, more importantly, suggest that LES dysfunction may be the initial cause, similar to pseudoachalasia, at least in postoperative cases. Thus, esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction, a disease per se according to the Chicago Classification, may be an achalasia variant or early form [50].

Apart from the LES, dysmotility exclusively of the esophageal body such as esophageal spasm can degenerate in achalasia. This deterioration occurs independently of LES dysfunction [51]. This may parallel some cases of pseudoachalasia with disease limited to the esophageal body sparing the LES such as aortic aneurysm compressing the esophagus [52]. These cases, however, are anecdotal cases, most without a previous workup to exclude the epiphenomenon of a conventional achalasia misdiagnosed until the presentation of the second disease [52].

Diagnosis

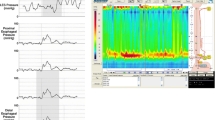

We mentioned before that pseudoachalasia has a clinical presentation undistinguishable from achalasia in terms of symptoms, manometric, and radiographic findings. For postoperative cases, the correct diagnosis demands preoperative demonstration of peristalsis and complete relaxation of the LES [24] (Fig. 1) since 45% of patients with untreated achalasia had been prescribed acid-suppressing medications on the assumption that gastroesophageal reflux disease was the cause of the symptoms [53], and misdiagnose of achalasia in patients that undergo antireflux operations may reach 4% [54].

High-resolution manometry tracings for pseudoachalasia after Nissen fundoplication. Esophageal motility is normal before operation (A), deteriorated to distal esophageal spams in 30 days after the operation (B), and finally aperistalsis and lack of relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter 4 months after the operation (C)

Some claim that pseudoachalasia symptoms may be of shorter duration with more pronounced weight loss and older age [8, 14, 15, 17, 55], but this is an occurrence usually in neoplastic pseudoachalasia due to cancer and not due to esophageal disease.

Some authors tried to find distinguishable manometric traits, such as compartmentalized pressurization or Chicago type [55, 56]. These findings, however, overlap with achalasia and are not extremely common or pathognomonic of pseudoachalasia.

Image tests (upper endoscopy, barium swallow, endoscopic ultrasound, and tomography) may obviously demonstrate the presence of a tumor as the cause, although some cases are not diagnostic [8, 18, 57, 58]. A feature in barium swallow that some authors point out is a longer segment of distal narrowing with a less marked esophageal dilatation [57,58,59].

Upper endoscopy may fail to reveal neoplastic infiltration in up to 60% of the cases and tomography in 20–100% [60,61,62,63].

Interestingly, fluoroscopy magnetic resonance seems to be a promising method [64].

Treatment

Since several etiologies could induce pseudoachalasia, management of this condition is variable.

Therapy is directed towards oncologic treatment in cases secondary to neoplasms. Symptoms may resolve with tumor remission and in some cases, peristalsis is restored [65,66,67]. Achalasia treatment may be used in cases of unresectable tumors in patients with severe symptoms. Outcomes of these procedures are shown in Table 1.

Precocious relief of reversible esophagogastric junction obstruction, if possible, may resolve the problem and even bring motility back to normal. This has been reported in cases of deflation or removal of adjustable gastric banding [28, 30, 31, 35] or drainage of a pseudocyst compressing the cardia [78]. Relief cannot be obtained if obstruction is chronic (over 8 years) [29].

Endoscopic forceful dilatation of the cardia is probably the most used treatment irrespective of etiology (Table 1). In our personal experience and others, dilatation after Nissen fundoplication is inefficient, and myotomy is necessary [68, 70]. Some believe that dysmotility may be reversible depending on the period for symptoms onset and dilatation with eventual anatomic repair is sufficient if symptoms occur early after a fundoplication [23] Conversion to partial fundoplication seldom solves symptoms [24, 71] (Table 1).

Heller’s myotomy and partial fundoplication always show good outcomes (Table 1), except perhaps with certain underlying conditions such as the coexistence of diffuse leiomyomatosis [79].

Peroral endoscopic myotomy (POEM) has been used after bariatric operations in a few cases, usually after the failure of other options (Table 1).

Conclusion

Pseudoachalasia is a rare condition. Most available evidence regarding this condition is based on case reports or small retrospective series. There are different causes but all culminating in outflow obstruction. Clinical presentation and image and functional tests overlap with primary achalasia or are inaccurate, thus the identification of secondary achalasia can be delayed. Inadequate diagnosis leads to futile therapies and could worsen prognosis, especially in neoplastic disease. Routine screening is not justifiable; good clinical judgment still remains the best tool [18]. Therapy should be aimed at etiology. Even though Heller’s myotomy brings the best results in non-malignant cases, again, good clinical judgment still remains the best tool.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

Lendrum FC (1937) Anatomic features of the cardiac orifice of the stomach with special reference to cardiospasm. Arch Intern Med 59:474–451

Yadlapati R, Kahrilas PJ, Fox MR et al (2021) Esophageal motility disorders on high-resolution manometry: Chicago classification version 4.0©. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 33(1):e14058. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.14058. (Erratum in: Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2022 5;:e14179)

Kahrilas PJ, Boeckxstaens G (2013) The spectrum of achalasia: lessons from studies of pathophysiology and high-resolution manometry. Gastroenterology 145:954–965

Ravi K, Sweetser S, Katzka DA (2016) Pseudoachalasia secondary to bariatric surgery. Dis Esophagus 29(8):992–995

Ogilvie H (1947) The early diagnosis of cancer of the oesophagus and stomach. Br Med J 2(4523):405–407. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.2.4523.405

Hejazi RA, Zhang D, McCallum RW (2009) Gastroparesis, pseudoachalasia and impaired intestinal motility as paraneoplastic manifestations of small cell lung cancer. Am J Med Sci 338(1):69–71. https://doi.org/10.1097/MAJ.0b013e31819b93e5

Song CW, Chun HJ, Kim CD, Ryu HS, Hyun JH, Kahrilas PJ (1999) Association of pseudoachalasia with advancing cancer of the gastric cardia. Gastrointest Endosc 50(4):486–491. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5107(99)70070-2

Parkman HP, Cohen S (1993) Malignancy-induced secondary achalasia. Dysphagia. 8(3):292–6 (Corrected and republished in: Dysphagia. 1994 9(2):292-6)

Moonka R, Pellegrini CA (1999) Malignant pseudoachalasia. Surg Endosc 13(3):273–275. https://doi.org/10.1007/s004649900962

Wehrli NE, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Katzka DA, Laufer I (2007) Secondary achalasia and other esophageal motility disorders after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication for gastroesophageal reflux disease. AJR Am J Roentgenol 189(6):1464–1468. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.07.2582

Casas MA, Schlottmann F, Herbella FAM, Buxhoeveden R, Patti MG (2019) Esophageal achalasia after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass for morbid obesity. Updates Surg 71(4):631–635. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13304-019-00688-3

Abu Ghanimeh M, Qasrawi A, Abughanimeh O, Albadarin S, Clarkston W (2017) Achalasia after bariatric Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery reversal. World J Gastroenterol 23(37):6902–6906. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v23.i37.6902

Suris X, Moyà F, Panés J, del Olmo JA, Solé M, Muñoz-Gómez J (1993) Achalasia of the esophagus in secondary amyloidosis. Am J Gastroenterol 88(11):1959–1960

Haj Ali SN, Nguyen NQ, Abu Sneineh AT (2021) Pseudoachalasia: a diagnostic challenge. When to consider and how to manage? Scand J Gastroenterol. 56(7):747–752. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365521.2021.1925957

Schizas D, Theochari NA, Katsaros I, Mylonas KS, Triantafyllou T, Michalinos A, Kamberoglou D, Tsekrekos A, Rouvelas I (2020) Pseudoachalasia: a systematic review of the literature. Esophagus 17(3):216–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10388-020-00720-1

Campo SM, Zullo A, Scandavini CM, Frezza B, Cerro P, Balducci G (2013) Pseudoachalasia: a peculiar case report and review of the literature. World J Gastrointest Endosc 5(9):450–454. https://doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v5.i9.450

Ponds FA, van Raath MI, Mohamed SMM, Smout AJPM, Bredenoord AJ (2017) Diagnostic features of malignancy-associated pseudoachalasia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 45(11):1449–1458. https://doi.org/10.1111/apt.14057

Katzka DA, Farrugia G, Arora AS (2012) Achalasia secondary to neoplasia: a disease with a changing differential diagnosis. Dis Esophagus 25:331–336

Fredens K, Tøttrup A, Kristensen IB, Dahl R, Jacobsen NO, Funch-Jensen P, Thommesen P (1989) Severe destruction of esophageal nerves in a patient with achalasia secondary to gastric cancer. A possible role of eosinophil neurotoxic proteins. Dig Dis Sci. 34(2):297–303. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01536066

Lee HR, Lennon VA, Camilleri M, Prather CM (2001) Paraneoplastic gastrointestinal motor dysfunction: clinical and laboratory characteristics. Am J Gastroenterol 96(2):373–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03454.x

Fabian E, Eherer AJ, Lackner C, Urban C, Smolle-Juettner FM, Krejs GJ (2019) Pseudoachalasia as first manifestation of a malignancy. Dig Dis 37(5):347–354. https://doi.org/10.1159/000495758

Lennon VA, Sas DF, Busk MF, Scheithauer B, Malagelada JR, Camilleri M, Miller LJ (1991) Enteric neuronal autoantibodies in pseudoobstruction with small-cell lung carcinoma. Gastroenterology 100(1):137–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(91)90593-a

Poulin EC, Diamant NE, Kortan P, Seshadri PA, Schlachta CM, Mamazza J (2000) Achalasia developing years after surgery for reflux disease: case reports, laparoscopic treatment, and review of achalasia syndromes following antireflux surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 4(6):626–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1091-255x(00)80113-4

Stylopoulos N, Bunker CJ, Rattner DW (2002) Development of achalasia secondary to laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication. J Gastrointest Surg 6:368–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1091-255X(02)00019-7

Awad ZT, Selima MA, Filipi CJ (2002) Pseudoachalasia as a late complication of gastric wrap performed for morbid obesity: report of a case. Surg Today 32(10):906–909. https://doi.org/10.1007/s005950200178

Myers JC, Jamieson GG, Wayman J, King DR, Watson DI (2007) Esophageal ileus following laparoscopic fundoplication. Dis Esophagus 20(5):420–427. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00643.x

Schwameis K, Ayazi S, Zaidi AH, Hoppo T, Jobe BA (2020) Development of pseudoachalasia following magnetic sphincter augmentation (MSA) with restoration of peristalsis after endoscopic dilation. Clin J Gastroenterol 13(5):697–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12328-020-01140-5

Arias IE, Radulescu M, Stiegeler R et al (2009) Diagnosis and treatment of megaesophagus after adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis 5(2):156–159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2008.11.007

Losh JM, Sanchez B, Waxman K (2017) Refractory pseudoachalasia secondary to laparoscopically placed adjustable gastric band successfully treated with Heller myotomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis 13(2):e4–e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2016.10.005

Khan A, Ren-Fielding C, Traube M (2011) Potentially reversible pseudoachalasia after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. J Clin Gastroenterol 45(9):775–779

Facchiano E, Scaringi S, Sabate JM et al (2007) Is esophageal dysmotility after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding reversible? Obes Surg 17(6):832–835

Wiesner W, Hauser M, Schöb O, Weber M, Hauser RS (2001) Pseudo-achalasia following laparoscopically placed adjustable gastric banding. Obes Surg 11(4):513–518. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089201321209440

Robert M, Golse N, Espalieu P et al (2012) Achalasia-like disorder after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: a reversible side effect? Obes Surg 22(5):704–711

Naef M, Mouton WG, Naef U, van der Weg B, Maddern GJ, Wagner HE (2011) Esophageal dysmotility disorders after laparoscopic gastric banding–an underestimated complication. Ann Surg 253(2):285–290. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e318206843e

Lipka S, Katz S (2013) Reversible pseudoachalasia in a patient with laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Gastroenterol Hepatol (N Y) 9(7):469–471

Herbella FAM, Patti MG (2021) The Impact of bariatric procedures on esophageal motility. Foregut 1(3):268–276. https://doi.org/10.1177/26345161211043462

Campos GM, Mazzini GS, Altieri MS, Docimo S Jr, DeMaria EJ, Rogers AM (2021) Clinical Issues Committee of the American Society for metabolic and bariatric surgery. ASMBS position statement on the rationale for performance of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy before and after metabolic and bariatric surgery. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 17(5):837–847. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2021.03.007

Lemme EMO, Alvariz AC, Pereira GLC (2021) Esophageal functional disorders in the pre-operatory evaluation of bariatric surgery. Arq Gastroenterol. 58(2):190–194. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0004-2803.202100000-34

Jaffin BW, Knoepflmacher P, Greenstein R (1999) High prevalence of asymptomatic esophageal motility disorders among morbidly obese patients. Obes Surg 9(4):390–395. https://doi.org/10.1381/096089299765552990

Chuah SK, Kuo CM, Wu KL, Changchien CS, Hu TH, Wang CC, Chiu YC, Chou YP, Hsu PI, Chiu KW, Kuo CH, Chiou SS, Lee CM (2006) Pseudoachalasia in a patient after truncal vagotomy surgery successfully treated by subsequent pneumatic dilations. World J Gastroenterol. 12(31):5087–90. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v12.i31.5087

Sharp JR (1979) Mechanical and neurogenic factors in postvagotomy dysphagia. J Clin Gastroenterol 1(4):321–324. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004836-197912000-00008

Gelfand MD (1981) Irreversible esophageal motor dysfunction in postvagotomy dysphagia. Am J Gastroenterol 76(4):347–350

Duntemann TJ, Dresner DM (1995) Achalasia-like syndrome presenting after highly selective vagotomy. Dig Dis Sci 40(9):2081–2083. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02208682

Singhal S, Kirkpatrick DR, Masuda T, Gerhardt J, Mittal SK (2018) Primary and redo antireflux surgery: outcomes and lessons learned. J Gastrointest Surg 22(2):177–186. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-017-3480-4

Trus TL, Bax T, Richardson WS, Branum GD, Mauren SJ, Swanstrom LL, Hunter JG (1997) Complications of laparoscopic paraesophageal hernia repair. J Gastrointest Surg. 1(3):221–7; discussion 228. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1091-255x(97)80113-8

Little AG, Correnti FS, Calleja IJ, Montag AG, Chow YC, Ferguson MK, Skinner DB (1986) Effect of incomplete obstruction on feline esophageal function with a clinical correlation. Surgery 100(2):430–436

Schneider JH, Peters JH, Kirkman E, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR (1999) Are the motility abnormalities of achalasia reversible? An experimental outflow obstruction in the feline model. Surgery 125(5):498–503

McKellar SH, Allen MS, Cassivi SD, Nichols FC 3rd, Shen KR, Wigle DA, Deschamps C (2011) Laparoscopic conversion from Nissen to partial fundoplication for refractory dysphagia. Ann Thorac Surg 91(3):932–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.07.090

Galey KM, Wilshire CL, Niebisch S, Jones CE, Raymond DP, Litle VR, Watson TJ, Peters JH (2011) Atypical variants of classic achalasia are common and currently under-recognized: a study of prevalence and clinical features. J Am Coll Surg. 213(1):155–61; discussion 162-3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.02.008

Bredenoord AJ, Babaei A, Carlson D, Omari T, Akiyama J, Yadlapati R, Pandolfino JE, Richter J, Fass R (2021) Esophagogastric junction outflow obstruction. Neurogastroenterol Motil 33(9):e14193. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.14193

Fontes LH, Herbella FA, Rodriguez TN, Trivino T, Farah JF (2013) Progression of diffuse esophageal spasm to achalasia: incidence and predictive factors. Dis Esophagus 26(5):470–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2050.2012.01377.x

Dejaeger M, Lormans M, Dejaeger E, Fagard K (2020) Case report: an aortic aneurysm as cause of pseudoachalasia. BMC Gastroenterol. 20(1):63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-020-01198-y

Fisichella PM, Raz D, Palazzo F, Niponmick I, Patti MG (2008) Clinical, radiological, and manometric profile in 145 patients with untreated achalasia. World J Surg 32(9):1974–1979. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-008-9656-z

Floch NR, Hinder RA, Klingler PJ, Branton SA, Seelig MH, Bammer T, Filipi CJ (1999) Is laparoscopic reoperation for failed antireflux surgery feasible? Arch Surg 134(7):733–737. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.134.7.733

Gergely M, Mello MD, Rengarajan A, Gyawali CP (2021) Duration of symptoms and manometric parameters offer clues to diagnosis of pseudoachalasia. Neurogastroenterol Motil 33(1):e13965. https://doi.org/10.1111/nmo.13965

Sutton RA, Gabbard SL (2017) High-resolution esophageal manometry findings in malignant pseudoachalasia. Dis Esophagus. 30(12):1–3. https://doi.org/10.1093/dote/dox095

Gupta P, Debi U, Sinha SK, Thapa BR, Prasad K (2015) Primary versus secondary achalasia: a diagnostic conundrum. Trop Gastroenterol 36(2):86–95. https://doi.org/10.7869/tg.259

Gupta P, Debi U, Sinha SK, Prasad KK (2015) Primary versus secondary achalasia: new signs on barium esophagogram. Indian J Radiol Imaging 25(3):288–295. https://doi.org/10.4103/0971-3026.161465

Woodfield CA, Levine MS, Rubesin SE, Langlotz CP, Laufer I (2000) Diagnosis of primary versus secondary achalasia: reassessment of clinical and radiographic criteria. AJR Am J Roentgenol 175(3):727–731. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.175.3.1750727

Licurse MY, Levine MS, Torigian DA, Barbosa EM Jr (2014) Utility of chest CT for differentiating primary and secondary achalasia. Clin Radiol 69(10):1019–1026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crad.2014.05.005

Moonka R, Patti MG, Feo CV, Arcerito M, De Pinto M, Horgan S, Pellegrini CA (1999) Clinical presentation and evaluation of malignant pseudoachalasia. J Gastrointest Surg 3(5):456–461. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1091-255x(99)80097-3

Carter M, Deckmann RC, Smith RC, Burrell MI, Traube M (1997) Differentiation of achalasia from pseudoachalasia by computed tomography. Am J Gastroenterol 92(4):624–628

Tracey JP, Traube M (1994) Difficulties in the diagnosis of pseudoachalasia. Am J Gastroenterol 89(11):2014–2018

Kulinna-Cosentini C, Schima W, Ba-Ssalamah A, Cosentini EP (2014) MRI patterns of Nissen fundoplication: normal appearance and mechanisms of failure. Eur Radiol 24(9):2137–2145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-014-3267-x

Nasa M, Bhansali S, Choudhary NS, Sud R (2018) Uncommon cause of dysphagia: paraneoplastic achalasia. BMJ Case Rep. 2018(7):bcr2017223929. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2017-223929

Ulla JL, Fernandez-Salgado E, Alvarez V, Ibañez A, Soto S, Carpio D, Vazquez-Sanluis J, Ledo L, Vazquez-Astray E (2008) Pseudoachalasia of the cardia secondary to nongastrointestinal neoplasia. Dysphagia 23(2):122–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00455-007-9104-5

Branchi F, Tenca A, Bareggi C, Mensi C, Mauro A, Conte D, Penagini R (2016) A case of pseudoachalasia hiding a malignant pleural mesothelioma. Tumori 102(Suppl. 2). https://doi.org/10.5301/tj.5000521

Bonavina L, Bona D, Saino G et al (2007) Pseudoachalasia occurring after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication and crural mesh repair. Langenbecks Arch Surg 392:653–656

Harbaugh JW, Clayton SB (2020) Pseudoachalasia Following Nissen fundoplication. ACG Case Rep J 7(2):e00318. https://doi.org/10.14309/crj.0000000000000318.

Ellingson TL, Kozarek RA, Gelfand MD, Botoman AV, Patterson DJ (1995) Iatrogenic achalasia. A case series J Clin Gastroenterol 20(2):96–99. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004836-199503000-00004

Gockel I, Eckardt VF, Schmitt T, Junginger T (2005) Pseudoachalasia: a case series and analysis of the literature. Scand J Gastroenterol 40(4):378–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/00365520510012118

Ramos AC, Murakami A, Lanzarini EG, Neto MG, Galvão M (2009) Achalasia and laparoscopic gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis 5(1):132–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soard.2008.05.004

Torghabeh MH, Afaneh C, Saif T, Dakin GF (2015) Achalasia 5 years following Roux-en-y gastric bypass. J Minim Access Surg 11(3):203–204. https://doi.org/10.4103/0972-9941.159854

Kolb JM, Jonas D, Funari MP, Hammad H, Menard-Katcher P, Wagh MS (2020) Efficacy and safety of peroral endoscopic myotomy after prior sleeve gastrectomy and gastric bypass surgery. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 12(12):532–541. https://doi.org/10.4253/wjge.v12.i12.532

Aiolfi A, Foschi D, Zappa MA, Dell’Era A, Bareggi E, Rausa E, Micheletto G, Bona D (2021) Laparoscopic Heller myotomy and Dor fundoplication for the treatment of esophageal achalasia after sleeve gastrectomy-a video vignette. Obes Surg 31(3):1392–1394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-020-05114-x

Dufour JF, Fawaz KA, Libby ED (1997) Botulinum toxin injection for secondary achalasia with esophageal varices. Gastrointest Endosc 45(2):191–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70248-7

Fishman VM, Parkman HP, Schiano TD, Hills C, Dabezies MA, Cohen S, Fisher RS, Miller LS (1996) Symptomatic improvement in achalasia after botulinum toxin injection of the lower esophageal sphincter. Am J Gastroenterol 91(9):1724–1730

Woods CA, Foutch PG, Waring JP, Sanowski RA (1989) Pancreatic pseudocyst as a cause for secondary achalasia. Gastroenterology 96(1):235–239. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-5085(89)90786-5

Sousa RG, Figueiredo PC, Pinto-Marques P, Meira T, Novais LA, Vieira AI, Luz C, Borralho P, Freitas J (2013) An unusual cause of pseudoachalasia: the Alport syndrome-diffuse leiomyomatosis association. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 25(11):1352–1357. https://doi.org/10.1097/MEG.0b013e328361dd17

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LYKZ: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and final approval of the version to be published. FAMH: conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting the article, and final approval of the version to be published. VV: conception and design, review for intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published. MGP: conception and design, review for intellectual content, and final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zanini, L.Y.K., Herbella, F.A.M., Velanovich, V. et al. Modern insights into the pathophysiology and treatment of pseudoachalasia. Langenbecks Arch Surg 409, 65 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-024-03259-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00423-024-03259-2