Abstract

Aged canines naturally accumulate several types of neuropathology that may have links to cognitive decline. On a gross level, significant cortical atrophy occurs with age along with an increase in ventricular volume based on magnetic resonance imaging studies. Microscopically, there is evidence of select neuron loss and reduced neurogenesis in the hippocampus of aged dogs, an area critical for intact learning and memory. The cause of neuronal loss and dysfunction may be related to the progressive accumulation of toxic proteins, oxidative damage, cerebrovascular pathology, and changes in gene expression. For example, aged dogs naturally accumulate human-type beta-amyloid peptide, a protein critically involved with the development of Alzheimer’s disease in humans. Further, oxidative damage to proteins, DNA/RNA and lipids occurs with age in dogs. Although less well explored in the aged canine brain, neuron loss, and cerebrovascular pathology observed with age are similar to human brain aging and may also be linked to cognitive decline. Interestingly, the prefrontal cortex appears to be particularly vulnerable early in the aging process in dogs and this may be reflected in dysfunction in specific cognitive domains with age.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The fastest growing segment of our population is individuals over the age of 85 years with the growth rate of those over 65 years doubling by the middle of the century (http://www.census.gov/population/www/pop-profile/elderpop.html). Increasing longevity however, raises the risk of developing age-associated neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Thus, identifying approaches that can promote healthy brain aging and reduce the risk of developing disease is critical. To do this, animal models can provide significant advances in identifying and testing preventive and/or therapeutic approaches to maintain healthy brain function.

There are many animal models of human brain aging from rodents up to nonhuman primates. Each has unique advantages but also associated challenges. For example, rodents are easily available, relatively inexpensive, and develop some of the same brain aging changes as observed in humans. Transgenic mice, in particular, have been instrumental to our understanding of aging and age-associated disease and allow researchers to identify proteins or processes that can be targets for therapeutics. Nonhuman primates are the closest evolutionarily to humans and exhibit higher order cognitive abilities, but are more difficult to obtain, have very long lifespans and are expensive to use in long-term treatment studies. Thus, it is important to consider many different model systems and to take advantage of unique features of each to provide robust data that can be applied to promoting successful aging in humans.

The aged canine naturally develops several similar features to human aging. Some aged dogs develop sufficient deficits in cognitive function and extensive neuropathology that resembles a spectrum encompassing mild cognitive impairment and possibly early AD in humans (Cotman and Head 2008). As discussed by Milgram et al. (this issue), aged dogs develop learning and memory deficits with age. Further, as with human aging, not all old dogs are equally affected and some remain cognitively intact whereas others develop significant dysfunction. Studying the brain changes of cognitively characterized dogs provides critical insights into the neurobiological basis for functional decline. These studies can be both correlative and hypothesis driven using targeted intervention strategies to measure outcomes on cognition and brain pathology. Work from our laboratory and others has established several key links between both cognitive or clinical decline (as measured in companion animals through veterinary clinicians) and neuropathology using various methodological approaches. These can range from macroscopic changes (e.g., brain atrophy), microscopic (e.g., beta-amyloid (Aβ) plaques, neuron loss), molecular changes (changes in specific proteins, receptors) to genetic modifications (changes in gene expression).

The dog is a domesticated subspecies of the wolf and includes over 400 different breeds (Parker et al. 2004). There can be significant variation in longevity in dogs depending on their breed, body weight, and environment. Typically, larger breeds of dogs have shorter lifespans than smaller breeds (Patronek et al. 1997; Galis et al. 2007; Greer et al. 2007). Thus, a unique feature to studying dog aging is addressing studies to genetic and environmental factors associated with longevity. But also, there is a suggestion that brain pathology, including the age of onset and extent may vary across breeds (Bobik et al. 1994). In laboratory beagles, the median lifespan (i.e., 50% have died) can be as high as 12–14 years depending on the colony evaluated (Lowseth et al. 1990; Albert et al. 1994). Of note, there are examples of “exceptional longevity” in pet/companion dogs (Cooley et al. 2003) consistent with increasing numbers of “oldest-old” human in our aging population (Head et al. 2007).

There are several ways to estimate the relationship between human and beagle age. It is estimated that 5.5–7 human years is approximately equivalent to 1 year of a beagle life (Albert et al. 1994). Alternative polynomial modeling suggests that beagles considered to be “aged” are over 9 years of age, which represents humans between the ages of 66–96 years (Patronek et al. 1997). Using this same model, middle aged beagles are between 5 and 9 years (∼40–60 years in humans) and young beagles are under 5 years (<40 years).

Macroscopic brain changes with age in the dog

Considerable variability in the weight or volume of the canine brain can occur depending on the size of the animal and breed. Indeed, it was this same variability that led to a shift away from using dogs in early psychological research. However, despite this confound, there are consistent and robust gross changes in brain structure that have been observed in aging animals. In vivo cross-sectional imaging studies show cortical atrophy (Su et al. 1998) and ventricular widening (Su et al. 1998; Gonzalez-Soriano et al. 2001; Kimotsuki et al. 2005) occurs with age in dogs. More recent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies suggest differential vulnerabilities of specific areas of cortex to aging. For example, the prefrontal cortex loses tissue volume at an earlier age than the hippocampus in aging beagles (Tapp et al. 2004). The hippocampus also shows progressive atrophy reaching significantly lower volumes when animals are over 11 years compared to young adult dogs. In longitudinal studies of MRI changes in brain structure, over a 3-year period of time, aged dogs showed progressive widening of the lateral ventricles but additional cortical atrophy was not observed (Su et al. 2005). Spontaneous lesions in the prefrontal cortex and the caudate nucleus were noted in increasing numbers of animals over the 3-year period; however, these lesions appeared to be clinically silent. There is a significant association between the extent of cortical atrophy and cognition; animals with more extensive atrophy perform more poorly on tests of learning and memory (Tapp et al. 2004). These results were confirmed in neurobiological experiments in a study of 30 dogs demonstrating a correlation between cortical atrophy (measured in coronal sections) and cognitive dysfunction (Rofina et al. 2006) similar to that seen in humans (Ezekiel et al. 2004; Du et al. 2005).

Interestingly, cortical and subcortical volume variation in measures of atrophy occurs as a function of sex in dogs (Tapp et al. 2006) suggesting differential vulnerabilities to the aging process in both gray and white matter in males and females. For these experiments, voxel-based morphometry analyses of MRI scans were used in a study of 62 beagles (31 males, 31 females) from 6 months to 15 years of age (Tapp et al. 2006). Although several regions show overlap in the extent of cortical atrophy as a function of age in males and females, such as in the parietal cortex, the prefrontal cortex shows larger losses in males relative to females. In contrast, females show larger losses of volume in the temporal cortex. Additional differences were noted in the white matter of aged males and females. Although both males and females showed equivalent atrophy of the internal capsula, females showed greater atrophy of the alveus of the hippocampus relative to males. Males, on the other hand, showed a reduction in the white matter tract volume of the optic nerve bundle. Although we have not observed any significant differences in cognition or in neuropathology between males and females, these results suggest that there may be differential structural changes with age as a function of sex in dogs. There have been similar patterns of gender-associated structural aging also reported in the human literature (e.g., Coffey et al. 1998). Female beagles undergo a progressive rather than abrupt (i.e., menopause) loss of reproductive ability with age but to what extent changes in hormonal status affect brain structures has not been explored.

Neuronal changes with age

Cortical atrophy, particularly in the hippocampus may result as a consequence of neuron loss, as reported in normal human brain aging (West 1993; Simic et al. 1997) with more extensive losses occurring in AD (Bobinski et al. 1997; West et al. 2000). Neurons were counted using unbiased stereological methods within individual subfields of the hippocampus and in the entorhinal cortex of young and aged beagles. The hilus of the dentate gryus showed a significant loss of neurons (∼30%) in the aged brain compared to young dogs (Siwak-Tapp et al. 2008). Although the sample size was relatively small (n = 5 young, n = 5 old), there was individual variability in numbers of hilar neurons in aged animals but only one aged dog (14.2 years) had hilar neuron counts within the range of the young dogs. To some extent, this variability related to cognitive function, dogs with higher numbers of neurons performed a size discrimination task, thought to be dependent on the medial temporal lobe, with fewer errors. Differences in neuron number were not detected in the remaining regions sampled including areas CA1, CA3, dentate granule cells, subiculum, and entorhinal cortex. Additional work is warranted as neuron loss has been reported in other dog hippocampal aging studies (Hwang et al. 2007; Hwang et al. 2008c) and in Purkinje cell loss in the cerebellum (Pugliese et al. 2007). The types of neurons lost with age may also have significant functional effects, and thus absolute number may not be as critical as the downstream consequences. For example and as will be described in a later section, γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)ergic, adrenergic, and serontonergic neurons are lost with age in dogs and would be predicted to have an impact on cognition.

Neurons lost with age may die through apoptotic mechanisms. Apoptosis is a highly regulated program of molecular pathways that lead to neuron shrinkage, DNA fragmentation, and activation of executioner enzymes called caspases (Rohn and Head 2008). Dogs over the age of 6 years show evidence of DNA fragmentation in both neurons and astrocytes that is correlated with behavioral dysfunction (Kiatipattanasakul et al. 1996) and with the extent of Aβ (Anderson et al. 2000). However, the presence of DNA fragmentation may also signal increasing DNA fragility with age (Borras et al. 2000). DNA fragmentation and the suggestion of apoptotic cell death have also been reported in the AD brain (Rohn and Head 2008) suggesting that both in human and canine brain, there may be similar pathogenic events (e.g., Aβ) that trigger neuron death.

Reduced neurogenesis may also contribute to age-associated cognitive decline and may be another mechanism underlying increasing cortical atrophy with age. The hippocampus is capable of generating new neurons in the subgranular layer throughout life (Eriksson et al. 1998), which can contribute to improvements in behavioral function (van Praag et al. 2002). To determine if aged beagles show changes in neurogenesis, counts of new neurons in the subgranular layer of the dentate gyrus labeled by bromodeoxyuridine given to animals prior to euthanasia have been reported. A significant loss in neurogenesis (90–95%) with age was observed in beagles over the age of 13 years (Siwak-Tapp et al. 2007). Further, the number of new neurons that were generated was correlated with cognitive function; animals with lower new neuron numbers had higher error scores of measures of learning and memory sensitive to medial temporal lobe function (Siwak-Tapp et al. 2007). Similar losses in neurogenesis have been reported in other laboratories using doublecortin protein as a marker of newly generated or differentiated neurons (Brown et al. 2003; Rao and Shetty 2004). Doublecortin protein levels are reduced by 80% in the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus in aging dogs (Hwang et al. 2007) and up to 96% in another study (Pekcec et al. 2008). Reduced doublecortin may not, however, be related to diffuse Aβ that can be present in aged dog brain (Pekcec et al. 2008).

Neuron loss in the canine brain with age is selective to brain subregions and to specific phenotypes and may proceed through apoptotic pathways. In addition to neuron loss, the ability to replace neurons through neurogenesis also appears impaired with age in the dog brain. In combination, loss of neurons and neurogenesis may both contribute to impaired cognitive function.

Aβ pathology

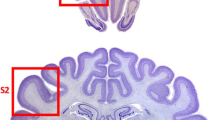

Neuron loss and cortical atrophy in vulnerable brain regions of the aged dog may be due to the accumulation of pathological proteins. Dogs deposit endogenous levels of Aβ that has an identical amino acid sequence to humans (Selkoe et al. 1987; Johnstone et al. 1991) and with similar posttranslational vulnerabilities (e.g., oxidation, racemization, isomerization; Satou et al. 1997; Azizeh et al. 2000) as they age. The dog β-amyloid precursor protein (APP) is virtually identical to human APP (∼98% homology), as established from the sequence published online for the dog genome (http://www.ensembl.org/Canis_familiaris/). Most of the deposits in the dog brain are of the diffuse subtype, but are fibrillar at the ultrastructural level and at an advanced stage, which models early plaque formation in humans (Torp et al. 2000a, b; Torp et al. 2003). We also observe intracellular Aβ using immunohistochemistry (Cummings et al. 1996b). Our work and the work of others demonstrate that specific brain regions show differential accumulation of Aβ, paralleling some reports in the aged human brain (Wisniewski et al. 1970; Selkoe et al. 1987; Giaccone et al. 1990; Wisniewski et al. 1990; Braak and Braak 1991; Ishihara et al. 1991; Braak et al. 1993; Head et al. 2000; Thal et al. 2002). When cortical regions are sampled for Aβ deposition, each region shows a different age of Aβ onset (Head et al. 2000). Aβ deposition occurs earliest in the prefrontal cortex of the dog and later in temporal and occipital cortex. Dog Aβ deposition follows a similar, although not identical, pattern of accumulation as reported in human brain. In the aging human brain, Aβ also appears early in neocortical regions, including the frontal cortex, with entorhinal and hippocampal Aβ appearing later, particularly with AD (Thal et al. 2002). Braak et al. also observe the earliest deposits of Aβ in the neocortex and particularly within basal portions of the frontal, temporal, and occipital lobes while the hippocampus remains devoid of pathology until later stages of AD (Braak and Braak 1991).

The extent of Aβ plaque deposition in the dog brain is linked to the severity of cognitive deficits (Cummings et al. 1996a; Head et al. 1998; Colle et al. 2000; Rofina et al. 2006). Age and cognitive status can predict Aβ pathology in discrete brain structures. For example, dogs with prefrontal cortex-dependent reversal learning deficits show significantly higher amounts of Aβ in this brain region (Cummings et al. 1996a, b, c, d; Head et al. 1998). On the other hand, dogs deficient on a size discrimination learning task, thought to be sensitive to temporal lobe function, show large amounts of Aβ deposition in the entorhinal cortex (Head et al. 1998). As in laboratory beagles, the extent of Aβ plaques varies as a function of age in companion dogs (including a wide variety of breeds and mixed breeds; Rofina et al. 2003; Rofina et al. 2004; Rofina et al. 2006). Further, the extent of Aβ plaques correlates with behavior changes and this association remains significant even if age is removed as a covariate (Colle et al. 2000; Rofina et al. 2006). Aβ plaques in the parietal lobe correlate with behavioral changes in aged companion animals related to appetite, drinking, incontinence, day and night rhythm, social behavior (interaction with owners and other dogs; personality), orientation, perception, and memory (Rofina et al. 2006). Interestingly, the accumulation of Aβ plaques in the brains of dogs does not begin until approximately 8 years of age. Thus, cognition declines prior to Aβ plaque accumulation and we hypothesize that cognitive impairment may be more tightly coupled to the production of toxic soluble assembly states of Aβ as reported in transgenic mice (Westerman et al. 2002; Lacor et al. 2004; Oddo et al. 2006). Consistent with this hypothesis, selective clearance of pre-existing Aβ diffuse plaques, but not soluble assembly states of Aβ, from the brains of aged dogs using active vaccination therapy does not lead to immediate improvements in learning (Head et al. 2008). However, prolonged treatment and reduction of Aβ is associated with a maintenance of prefrontal–cortex function over time (>2 years; Head et al. 2008). Thus, although there is good correlative evidence that Aβ contributes to cognitive decline in aged dogs, other pathologies may also make a significant contribution particularly in middle age such as cerebrovascular dysfunction, progressive oxidative damage, neurotransmitter systems changes, and alterations in gene expression.

Cerebrovascular pathology

A common type of pathology observed in both normal human brain aging and particularly in AD is the accumulation of cerebrovascular amyloid angiopathy (CAA; Attems 2005; Attems et al. 2005; Herzig et al. 2006). CAA, involving the deposition of Aβ in association with blood vessels, may compromise the blood brain barrier, impair vascular function (constriction and dilation; Prior et al. 1996b), and cause microhemorrhages (Deane and Zlokovic 2007). CAA in the dog brain was first observed by Braunmuhl (1956) as early as 1956 and was subsequently confirmed by Wisniewski et al. (1990). Vascular and perivascular abnormalities and cerebrovascular Aβ pathology are frequently found in aged dogs (Giaccone et al. 1990; Uchida et al. 1990; Ishihara et al. 1991; Uchida et al. 1991; Shimada et al. 1992a; Uchida et al. 1992, 1993; Yoshino et al. 1996; Uchida et al. 1997). Cultured vascular smooth muscle cells from dog brain can mimic the pathological process (e.g., Aβ production and accumulation) that occurs in humans with AD and Down syndrome (Frackowiak et al. 1995; Prior et al. 1995, 1996a, b). Vascular Aβ is primarily the shorter 1–40 species, which is identical in dogs and humans (Wisniewski et al. 1996). Dog CAA can be associated with cerebral hemorrhage (Uchida et al. 1990; Uchida et al. 1991) and the distribution of CAA in dog brain also appears similar to humans with the occipital cortex being particularly vulnerable (Attems et al. 2005). The extent of CAA in aged dog brains can correlate with clinical signs of cognitive dysfunction in companion dogs (Colle et al. 2000). Overall, dogs are thought to be a good natural model for examining CAA and treatments for CAA (Walker 1997). Cerebrovascular pathology may contribute to impaired vasodilation or vasoconstriction, leakage of the blood brain barrier, and potentially reduced blood volume and flow to the brain. In turn, over time, reduced blood flow may lead to neuronal dysfunction and death and deficits in cognitive function.

Oxidative damage and inflammation

Aging and the production of free radicals can lead to oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and nucleotides that, in turn, may cause neuronal dysfunction and ultimately neuronal death. Normally, several mechanisms are in place that balances the production of free radicals such as endogenous antioxidants. However with age, a number of these protective mechanisms begin to fail. In AD, oxidative damage is particularly pronounced and significant increases in protein oxidation, lipid peroxidation and DNA/RNA oxidation have all been reported (Smith et al. 1991; Ames et al. 1993; Smith et al. 1996, 2000; Pratico et al. 1998; Lovell et al. 1999; Montine et al. 1999; Pratico and Delanty 2000; Montine et al. 2002; Pratico et al. 2002; Butterfield 2004; Butterfield et al. 2007; Butterfield and Sultana 2007; Lovell and Markesbery 2007b, 2008). Further, in humans with MCI, which is thought to represent early AD (Petersen et al. 1999; Morris et al. 2001), already show either intermediate or similar levels of oxidative damage as observed in AD (Pratico et al. 2002; Rinaldi et al. 2003; Keller et al. 2005; Butterfield et al. 2007; Butterfield and Sultana 2007; Lovell and Markesbery 2007a, b; Markesbery and Lovell 2007; Lovell and Markesbery 2008). There are a number of downstream consequences of oxidative modifications to proteins, lipids and DNA/RNA including a reduction in protein synthesis (Ding et al. 2007), altered proteasome function (Ding and Keller 2001), and impaired protein/enzyme function (Stadtman 1992; Stadtman and Berlett 1997). Further, selective oxidative modifications to key proteins identified using proteomics approaches may lead to neuronal dysfunction through abnormalities in pathways associated with energy metabolism, excitotoxicity, proteasomal dysfunction, lipid, synaptic dysfunction, and pH buffering (Butterfield and Sultana 2007).

In dog brain, carbonyl groups, which are a measure of oxidative damage to proteins, accumulates with age (Head et al. 2002; Skoumalova et al. 2003b) and is associated with reduced endogenous antioxidant enzyme activity or protein levels such as in glutamine synthetase and superoxide dismutase (Kiatipattanasakul et al. 1997; Head et al. 2002; Hwang et al. 2008a; Opii et al. 2008). In several studies, a relation between age and increased oxidative damage has been inferred by measuring the amount of end products of lipid peroxidation (oxidative damage to lipids) including the extent of 4-hydroxynonenal (Papaioannou et al. 2001; Rofina et al. 2004; Rofina et al. 2006; Hwang et al. 2008a), lipofuscin (Rofina et al. 2006), lipofuscin-like pigments (Papaioannou et al. 2001; Rofina et al. 2004), or malondialdehyde (Head et al. 2002). Last, evidence of increased oxidative damage to DNA or RNA (8O HdG) in aged dog brain has been reported (Rofina et al. 2006), a feature we have also subsequently observed (Cotman and Head 2008).

Oxidative damage may also be associated with behavioral decline in dogs. Rofina et al. found that increased oxidative end products (lipofuscin-like pigment and protein carbonyls) in aged companion dog brain (including several breeds and mixed breeds; Skoumalova et al. 2003a; Rofina et al. 2004; Rofina et al. 2006) correlate with severity of behavior changes due to cognitive dysfunction. Similarly, in our own studies of aging beagles, higher protein oxidative damage (3-nitrotyrosine) and lower endogenous antioxidant capacity (superoxide dismutase and glutathione-S-transferase) are all associated with poorer prefrontal-dependent and spatial learning (Opii et al. 2008). These correlative studies suggest a link between cognition and progressive oxidative damage in the dog. Indeed, when aged dogs are provided with an antioxidant-enriched diet, significant cognitive improvements are observed (Cotman et al. 2002; Milgram et al. 2002; Milgram et al. 2004; Milgram et al. 2005) along with reduced oxidative damage to the brain (Opii et al. 2008). Similarly, providing dogs with a nutraceutical containing antioxidants such as vitamin E also leads to improvements in spatial memory (Araujo et al. 2008).

There are fewer studies describing inflammatory changes in the aged dog brain, which is a key feature of the aging human and AD brain (Akiyama et al. 2000). Gliosis has been reported with increasing age in the canine cerebellum and hippocampus (Shimada et al. 1992b; Kiatipattanasakul et al. 1998; Pugliese et al. 2006; Pugliese et al. 2007; Hwang et al. 2008d). However, as opposed to the AD brain, increased neuroinflammatory cells have not be found in association with canine Aβ deposits, which are diffuse in nature (Cummings et al. 1996c). As will be described in a later section, there is evidence to suggest that gene expression associated with inflammatory processes is increased with age in dogs.

Neurotransmitter systems and aging

Neurotransmitter deficits as a function of age in the dog have not been as well explored as in human aging and disease. Of the limited studies reported, similar neurotransmitter system losses and changes appear to occur in the canine brain as with the human brain during aging and AD (Meltzer et al. 1998; Ballard et al. 2005; Schliebs and Arendt 2006; Rissman et al. 2007). In the aged canine dorsal and median raphe nuclei, there appears to be no significant losses in tryptophan hydroxylase positive neurons estimated using unbiased stereology methods (Bernedo et al. 2009). However, significant losses in serotonergic neurons were observed in aged dogs with Aβ plaque accumulation in the gyrus proreus (a region of the prefrontal cortex; Bernedo et al. 2009). In vivo receptor binding, using single photon emission tomography and a selective 5-HT2A receptor ligand also decreases in dogs over the age of 8 years particularly in the front-cortical region with a significant negative correlation with age in the right fronto-cortical region (Peremans et al. 2002).

Similar outcomes were observed in a study of locus ceruleus noradrenergic neurons labeled by tyrosine hydroxylase, with no age effects observed but lower numbers in dogs with higher Aβ plaques in the prefrontal cortex. Further, noradrenergic cell loss was associated with cognitive dysfunction (Insua et al. 2008). Acetylcholinesterase density, which may reflect cholinergic neurons in the cerebellum of dogs, was reduced in granule cells with age, although this was not associated with cognitive dysfunction (Pugliese et al. 2007). Further, providing aged dogs with the cholinergic agonist, phenserine, leads to improved complex discrimination learning in mildly impaired aged animals (Studzinski et al. 2005).

GABA interneuron losses in the prefrontal cortex of dogs aged 8–15 years old has also been reported (Pugliese et al. 2004). Specifically, neurons containing the calcium binding protein, calbindin, were depleted whereas parvalbumin or calretinin positive neurons remained intact (Pugliese et al. 2004). A similar lack of age-dependent losses of parvalbumin positive neurons was also reported for area CA1 and dentate gyrus of the hippocampus (Hwang et al. 2008b). An earlier study, however, did not observe calbindin D-28 k positive neurons in cortex but only in the cerebellum, which was decreased with advanced age in dogs (Siso et al. 2003). Consistent with (Ballard et al. 2005) prefrontal losses in GABAergic interneurons, hippocampal neurons positive for the rate-limiting enzyme for GABA synthesis, glutamic acid decarboxylase 67, were reduced in area CA1 in dogs 10 years and older (Hwang et al. 2008c). Thus, as with human aging and AD, dogs show modifications to the serontonergic, cholinergic, and GABAergic systems with age that in some studies is linked to Aβ accumulation and to cognitive dysfunction. Thus, some evidence suggests that the loss of neurotransmitter-producing neurons with age in the dog that parallel human brain aging and disease, which can make significant contributions to cognitive dysfunction.

Gene expression changes with age

With the development of microarray technology, it is now possible to obtain a broad view of the changes in gene expression that can occur with age across many species. In mice and humans, increases in expression of genes associated with inflammation, oxidative stress, and DNA repair have been consistently reported (Lee et al. 2000; Jiang et al. 2001; Weindruch et al. 2002; Lu et al. 2004; Erraji-Benchekroun et al. 2005). Further, decreases in expression for genes associated with neurotrophic support, mitochondrial function, and for synaptic plasticity are also consistently observed. Many of these events are exacerbated in AD relative to nondemented elderly controls (Blalock et al. 2004). Swanson et al. reported the first canine gene microarray study of aging comparing 12- to 1-year-old beagles (Swanson et al. 2007). The expression of 963 genes increased or decreased with age in the dog cortex. Transcripts that were upregulated in aged beagles included genes associated with apoptosis, cell signaling and signal transduction, cell development, cellular trafficking and protein processing, and immune function. In contrast, ATP synthesis, neurogenesis, metabolic and subsets of cellular trafficking, development, and protein processing all showed decreased gene expression. These canine brain changes are consistent with reports in other species and in humans and suggests conservation of specific gene families compromised with age.

Summary

Aged dogs naturally develop a broad spectrum of neuropathology and neurobiological changes that parallels observations in aging human, mild cognitive impairment, and early AD. Overall, the prefrontal cortex may be particularly vulnerable to the aging process as this region shows the earliest signs of atrophy, Aβ deposition, and additional changes such as 5-HT receptor dysfunction and oxidative damage. The hippocampus and medial temporal lobe also accumulate Aβ and selective neuron loss and dysfunction, consistent with human brain aging. The molecular and genetic pathways that are engaged and lead to neuronal dysfunction and losses have yet to be fully identified but may include oxidative damage, cerebrovascular, and metabolic changes and possibly reduced expression of genes involved with signal transduction, protein processing, neurogenesis, and neurotrophic support as indicated by microarray studies.

References

Akiyama H, Barger S, Barnum S, Bradt B, Bauer J, Cole GM, Cooper NR, Eikelenboom P, Emmerling M, Fiebich BL, Finch CE, Frautschy S, Griffin WST, Hampel H, Hull M, Landreth G, Lue L-F, Mrak R, Mackenzie IR, McGeer PL, O’Banion MK, Pachter J, Pasinetti G, Plata-Salaman C, Rogers J, Rydel R, Shen Y, Streit W, Strohmeyer R, Tooyoma I, Van Muiswinkel FL, Veerhuis R, Walker D, Webster S, Wegrzyniak B, Wenk G, Wyss-Coray T (2000) Inflammation and Alzheimer’s disease: Neuroinflammation Working Group. Neurobiol Aging 21:383–421

Albert RE, Benjamin SA, Shukla R (1994) Life span and cancer mortality in the beagle dog and humans. Mech Ageing Dev 74:149–159

Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM (1993) Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:7915–7922

Anderson AJ, Ruehl WW, Fleischmann LK, Stenstrom K, Entriken TL, Cummings BJ (2000) DNA damage and apoptosis in the aged canine brain: relationship to Ab deposition in the absence of neuritic pathology. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 24:787–799

Araujo JA, Landsberg GM, Milgram NW, Miolo A (2008) Improvement of short-term memory performance in aged beagles by a nutraceutical supplement containing phosphatidylserine, Ginkgo biloba, vitamin E, and pyridoxine. Can Vet J 49:379–385

Attems J (2005) Sporadic cerebral amyloid angiopathy: pathology, clinical implications, and possible pathomechanisms. Acta Neuropathol 110:345–359

Attems J, Jellinger KA, Lintner F (2005) Alzheimer’s disease pathology influences severity and topographical distribution of cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol 110:222–231

Azizeh BY, Head E, Ibrahim MA, Torp R, Tenner AJ, Kim RC, Lott IT, Cotman CW (2000) Molecular dating of senile plaques in aged down’s syndrome and canine brains. Exp Neurol 163:111–122

Ballard CG, Greig NH, Guillozet-Bongaarts AL, Enz A, Darvesh S (2005) Cholinesterases: roles in the brain during health and disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 2:307–318

Bernedo V, Insua D, Suarez ML, Santamarina G, Sarasa M, Pesini P (2009) Beta-amyloid cortical deposits are accompanied by the loss of serotonergic neurons in the dog. J Comp Neurol 513:417–429

Blalock EM, Geddes JW, Chen KC, Porter NM, Markesbery WR, Landfield PW (2004) Incipient Alzheimer’s disease: microarray correlation analyses reveal major transcriptional and tumor suppressor responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:2173–2178

Bobik M, Thompson T, Russell MJ (1994) Amyloid deposition in various breeds of dogs. Society for Neuroscience Abstracts 20 172

Bobinski M, Wegiel J, Tarnawski M, Bobinski M, Reisberg B, de Leon MJ, Miller DC, Wisniewski HM (1997) Relationships between regional neuronal loss and neurofibrillary changes in the hippocampal formation and duration and severity of Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 56:414–420

Borras D, Pumarola M, Ferrer I (2000) Neuronal nuclear DNA fragmentation in the aged canine brain: apoptosis or nuclear DNA fragility? Acta Neuropathol 99:402–408

Braak H, Braak E (1991) Neuropathological stageing of Alzheimer-related changes. Acta Neuropathol 82:239–259

Braak H, Braak E, Bohl J (1993) Staging of Alzheimer-related cortical destruction. Review in Clin Neurosci 33:403–408

Braunmuhl A (1956) Kongophile angiopathie und senile plaques bei greisen hunden. Arch Psychiatr Nervenkr 194:395–414

Brown JP, Couillard-Despres S, Cooper-Kuhn CM, Winkler J, Aigner L, Kuhn HG (2003) Transient expression of doublecortin during adult neurogenesis. J Comp Neurol 467:1–10

Butterfield DA (2004) Proteomics: a new approach to investigate oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease brain. Brain Res 1000:1–7

Butterfield DA, Sultana R (2007) Redox proteomics identification of oxidatively modified brain proteins in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: insights into the progression of this dementing disorder. J Alzheimers Dis 12:61–72

Butterfield DA, Reed T, Newman SF, Sultana R (2007) Roles of amyloid beta-peptide-associated oxidative stress and brain protein modifications in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment. Free Radic Biol Med 43:658–677

Coffey CE, Lucke JF, Saxton JA, Ratcliff G, Unitas LJ, Billig B, Bryan RN (1998) Sex differences in brain aging: a quantitative magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch Neurol 55:169–179

Colle M-A, Hauw J-J, Crespeau F, Uchiara T, Akiyama H, Checler F, Pageat P, Duykaerts C (2000) Vascular and parenchymal Ab deposition in the aging dog: correlation with behavior. Neurobiol Aging 21:695–704

Cooley DM, Schlittler DL, Glickman LT, Hayek M, Waters DJ (2003) Exceptional longevity in pet dogs is accompanied by cancer resistance and delayed onset of major diseases. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 58:B1078–B1084

Cotman CW, Head E (2008) The canine (dog) model of human aging and disease: dietary, environmental and immunotherapy approaches. J Alzheimers Dis 15:685–707

Cotman CW, Head E, Muggenburg BA, Zicker S, Milgram NW (2002) Brain aging in the canine: a diet enriched in antioxidants reduces cognitive dysfunction. Neurobiol Aging 23:809–818

Cummings BJ, Head E, Afagh AJ, Milgram NW, Cotman CW (1996a) Beta-amyloid accumulation correlates with cognitive dysfunction in the aged canine. Neurobiol Learn Mem 66:11–23

Cummings BJ, Head E, Ruehl WW, Milgram NW, Cotman CW (1996b) The canine as an animal model of human aging and dementia. Neurobiol Aging 17:259–268

Cummings BJ, Head E, Ruehl W, Milgram NW, Cotman CW (1996c) The canine as an animal model of human aging and dementia. Neurobiol Aging 17:259–268

Cummings BJ, Head E, Ruehl WW, Milgram NW, Cotman CW (1996d) Beta-amyloid accumulation correlates with cognitive dysfunction in the aged canine. Neurobiol Learn Mem 66:11–23

Deane R, Zlokovic BV (2007) Role of the blood-brain barrier in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 4:191–197

Ding Q, Keller JN (2001) Proteosomes and proteosome inhibition in the central nervous system. Free Radic Biol Med 31:574–584

Ding Q, Dimayuga E, Keller JN (2007) Oxidative damage, protein synthesis, and protein degradation in Alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 4:73–79

Du AT, Schuff N, Chao LL, Kornak J, Ezekiel F, Jagust WJ, Kramer JH, Reed BR, Miller BL, Norman D, Chui HC, Weiner MW (2005) White matter lesions are associated with cortical atrophy more than entorhinal and hippocampal atrophy. Neurobiol Aging 26:553–559

Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Bjork-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, Gage FH (1998) Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat Med 4:1313–1317

Erraji-Benchekroun L, Underwood MD, Arango V, Galfalvy H, Pavlidis P, Smyrniotopoulos P, Mann JJ, Sibille E (2005) Molecular aging in human prefrontal cortex is selective and continuous throughout adult life. Biol Psychiatry 57:549–558

Ezekiel F, Chao L, Kornak J, Du AT, Cardenas V, Truran D, Jagust W, Chui H, Miller B, Yaffe K, Schuff N, Weiner M (2004) Comparisons between global and focal brain atrophy rates in normal aging and Alzheimer disease: boundary shift integral versus tracing of the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 18:196–201

Frackowiak J, Mazur-Kolecka B, Wisniewski HM, Potempska A, Carroll RT, Emmerling MR, Kim KS (1995) Secretion and accumulation of Alzheimer’s beta-protein by cultured vascular smooth muscle cells from old and young dogs. Brain Res 676:225–230

Galis F, Van der Sluijs I, Van Dooren TJ, Metz JA, Nussbaumer M (2007) Do large dogs die young? J Exp Zoolog B Mol Dev Evol 308:119–126

Giaccone G, Verga L, Finazzi M, Pollo B, Tagliavini F, Frangione B, Bugiani O (1990) Cerebral preamyloid deposits and congophilic angiopathy in aged dogs. Neurosci Lett 114:178–183

Gonzalez-Soriano J, Marin GP, Contreras-Rodriguez J, Martinez-Sainz P, Rodriguez-Veiga E (2001) Age-related changes in the ventricular system of the dog brain. Ann Anat 183:283–291

Greer KA, Canterberry SC, Murphy KE (2007) Statistical analysis regarding the effects of height and weight on life span of the domestic dog. Res Vet Sci 82:208–214

Head E, Callahan H, Muggenburg BA, Cotman CW, Milgram NW (1998) Visual-discrimination learning ability and beta-amyloid accumulation in the dog. Neurobiol Aging 19:415–425

Head E, McCleary R, Hahn FF, Milgram NW, Cotman CW (2000) Region-specific age at onset of beta-amyloid in dogs. Neurobiol Aging 21:89–96

Head E, Liu J, Hagen TM, Muggenburg BA, Milgram NW, Ames BN, Cotman CW (2002) Oxidative damage increases with age in a canine model of human brain aging. J Neurochem 82:375–381

Head E, Corrada MM, Kahle-Wrobleski K, Kim RC, Sarsoza F, Goodus M, Kawas CH (2009) Synaptic proteins, neuropathology and cognitive status in the oldest-old. Neurobiol Aging 30(7):1125–1134

Head E, Pop V, Vasilevko V, Hill M, Saing T, Sarsoza F, Nistor M, Christie LA, Milton S, Glabe C, Barrett E, Cribbs D (2008) A two-year study with fibrillar beta-amyloid (Abeta) immunization in aged canines: effects on cognitive function and brain Abeta. J Neurosci 28:3555–3566

Herzig MC, Van Nostrand WE, Jucker M (2006) Mechanism of cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathy: murine and cellular models. Brain Pathol 16:40–54

Hwang IK, Yoo KY, Li H, Choi JH, Kwon YG, Ahn Y, Lee IS, Won MH (2007) Differences in doublecortin immunoreactivity and protein levels in the hippocampal dentate gyrus between adult and aged dogs. Neurochem Res 32:1604–1609

Hwang IK, Yoon YS, Yoo KY, Li H, Choi JH, Kim DW, Yi SS, Seong JK, Lee IS, Won MH (2008a) Differences in lipid peroxidation and Cu, Zn-superoxide dismutase in the hippocampal CA1 region between adult and aged dogs. J Vet Med Sci 70:273–277

Hwang IK, Yoon YS, Yoo KY, Li H, Sun Y, Choi JH, Lee CH, Huh SO, Lee YL, Won MH (2008b) Sustained expression of parvalbumin immunoreactivity in the hippocampal CA1 region and dentate gyrus during aging in dogs. Neurosci Lett 434(1):99–103

Hwang IK, Li H, Yoo KY, Choi JH, Lee CH, Chung DW, Kim DW, Seong JK, Yoon YS, Lee IS, Won MH (2008c) Comparison of glutamic acid decarboxylase 67 immunoreactive neurons in the hippocampal CA1 region at various age stages in dogs. Neurosci Lett 431:251–255

Hwang IK, Choi JH, Li H, Yoo KY, Kim DW, Lee CH, Yi SS, Seong JK, Lee IS, Yoon YS, Won MH (2008d) Changes in glial fibrillary acidic protein immunoreactivity in the dentate gyrus and hippocampus proper of adult and aged dogs. J Vet Med Sci 70:965–969

Insua D, Suarez ML, Santamarina G, Sarasa M, Pesini P (2010) Dogs with canine counterpart of Alzheimer’s disease lose noradrenergic neurons. Neurobiol Aging 31(4):625–635

Ishihara T, Gondo T, Takahashi M, Uchino F, Ikeda S, Allsop D, Imai K (1991) Immunohistochemical and immunoelectron microscopial characterization of cerebrovascular and senile plaque amyloid in aged dogs’ brains. Brain Res 548:196–205

Jiang CH, Tsien JZ, Schultz PG, Hu Y (2001) The effects of aging on gene expression in the hypothalamus and cortex of mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:1930–1934

Johnstone EM, Chaney MO, Norris FH, Pascual R, Little SP (1991) Conservation of the sequence of the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid peptide in dog, polar bear and five other mammals by cross-species polymerase chain reaction analysis. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 10:299–305

Keller JN, Schmitt FA, Scheff SW, Ding Q, Chen Q, Butterfield DA, Markesbery WR (2005) Evidence of increased oxidative damage in subjects with mild cognitive impairment. Neurology 64:1152–1156

Kiatipattanasakul W, Nakamura S, Hossain MM, Nakayama H, Uchino T, Shumiya S, Goto N, Doi K (1996) Apoptosis in the aged dog brain. Acta Neuropathol 92:242–248

Kiatipattanasakul W, Nakamura S, Kuroki K, Nakayama H, Doi K (1997) Immunohistochemical detection of anti-oxidative stress enzymes in the dog brain. Neuropathology 17:307–312

Kiatipattanasakul W, Nakayama H, Nakamura S-I, Doi K (1998) Lectin histochemistry in the aged dog brain. Acta Neuropathol 95:261–268

Kimotsuki T, Nagaoka T, Yasuda M, Tamahara S, Matsuki N, Ono K (2005) Changes of magnetic resonance imaging on the brain in beagle dogs with aging. J Vet Med Sci 67:961–967

Lacor PN, Buniel MC, Chang L, Fernandez SJ, Gong Y, Viola KL, Lambert MP, Velasco PT, Bigio EH, Finch CE, Krafft GA, Klein WL (2004) Synaptic targeting by Alzheimer’s-related amyloid beta oligomers. J Neurosci 24:10191–10200

Lee CK, Weindruch R, Prolla TA (2000) Gene-expression profile of the ageing brain in mice. Nat Genet 25:294–297

Lovell MA, Markesbery WR (2007a) Oxidative DNA damage in mild cognitive impairment and late-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Nucleic Acids Res 35:7497–7504

Lovell MA, Markesbery WR (2007b) Oxidative damage in mild cognitive impairment and early Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci Res 85:3036–3040

Lovell MA, Markesbery WR (2008) Oxidatively modified RNA in mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Dis 29:169–175

Lovell MA, Gabbita SP, Markesbery WR (1999) Increased DNA oxidation and decreased levels of repair products in Alzheimer’s disease ventricular CSF. J Neurochem 72:771–776

Lowseth LA, Gillett NA, Gerlach RF, Muggenburg BA (1990) The effects of aging on hematology and serum chemistry values in the beagle dog. Vet Clin Path 19:13–19

Lu T, Pan Y, Kao S-Y, Li C, Kohane I, Chan J, Yankner BA (2004) Gene regulation and DNA damage in the ageing human brain. Nature 429:883–891

Markesbery WR, Lovell MA (2007) Damage to lipids, proteins, DNA, and RNA in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 64:954–956

Meltzer CC, Smith G, DeKosky ST, Pollock BG, Mathis CA, Moore RY, Kupfer DJ, Reynolds CF III (1998) Serotonin in aging, late-life depression, and Alzheimer’s disease: the emerging role of functional imaging. Neuropsychopharmacology 18:407–430

Milgram NW, Head E, Muggenburg BA, Holowachuk D, Murphey H, Estrada J, Ikeda-Douglas CJ, Zicker SC, Cotman CW (2002) Landmark discrimination learning in the dog: effects of age, an antioxidant fortified diet, and cognitive strategy. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 26:679–695

Milgram NW, Head E, Zicker SC, Ikeda-Douglas C, Murphey H, Muggenberg BA, Siwak CT, Tapp DP, Lowry SR, Cotman CW (2004) Long-term treatment with antioxidants and a program of behavioral enrichment reduces age-dependent impairment in discrimination and reversal learning in beagle dogs. Exp Gerontol 39:753–765

Milgram NW, Head E, Zicker SC, Ikeda-Douglas CJ, Murphey H, Muggenburg B, Siwak C, Tapp D, Cotman CW (2005) Learning ability in aged beagle dogs is preserved by behavioral enrichment and dietary fortification: a two-year longitudinal study. Neurobiol Aging 26:77–90

Montine TJ, Beal MF, Cudkowicz ME, O’Donnell H, Margolin RA, McFarland L, Bachrach AF, Zackert WE, Roberts LJ, Morrow JD (1999) Increased CSF F2-isoprostane concentration in probable AD. Neurology 52:562–565

Montine TJ, Neely MD, Quinn JF, Beal MF, Markesbery WR, Roberts LJ, Morrow JD (2002) Lipid peroxidation in aging brain and Alzheimer’s disease. Free Radic Biol Med 33:620–626

Morris JC, Storandt M, Miller JP, McKeel DW, Price JL, Rubin EH, Berg L (2001) Mild cognitive impairment represents early-stage Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol 58:397–405

Oddo S, Caccamo A, Tran L, Lambert MP, Glabe CG, Klein WL, LaFerla FM (2006) Temporal profile of amyloid-beta (Abeta) oligomerization in an in vivo model of Alzheimer disease. A link between Abeta and tau pathology. J Biol Chem 281:1599–1604

Opii WO, Joshi G, Head E, Milgram NW, Muggenburg BA, Klein JB, Pierce WM, Cotman CW, Butterfield DA (2008) Proteomic identification of brain proteins in the canine model of human aging following a long-term treatment with antioxidants and a program of behavioral enrichment: relevance to Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging 29:51–70

Papaioannou N, Tooten PCJ, van Ederen AM, Bohl JRE, Rofina J, Tsangaris T, Gruys E (2001) Immunohistochemical investigation of the brain of aged dogs. I. Detection of neurofibrillary tangles and of 4-hydroxynonenal protein, an oxidative damage product, in senile plaques. Amyloid: J Protein Folding Disord 8:11–21

Parker HG, Kim LV, Sutter NB, Carlson S, Lorentzen TD, Malek TB, Johnson GS, DeFrance HB, Ostrander EA, Kruglyak L (2004) Genetic structure of the purebred domestic dog. Science 304:1160–1164

Patronek GJ, Waters DJ, Glickman LT (1997) Comparative longevity of pet dogs and humans: implications for gerontology research. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 52:B171–B178

Pekcec A, Baumgartner W, Bankstahl JP, Stein VM, Potschka H (2008) Effect of aging on neurogenesis in the canine brain. Aging Cell 7:368–374

Peremans K, Audenaert K, Blanckaert P, Jacobs F, Coopman F, Verschooten F, Van Bree H, Van Heeringen C, Mertens J, Slegers G, Dierckx R (2002) Effects of aging on brain perfusion and serotonin-2A receptor binding in the normal canine brain measured with single photon emission tomography. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 26:1393–1404

Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E (1999) Mild cognitive impairment: clinical characterization and outcome. Arch Neurol 56:303–308

Pratico D, Delanty N (2000) Oxidative injury in diseases of the central nervous system: focus on Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Med 109:577–585

Pratico D, Lee MY, Trojanowski JQ, Rokach J, Fitzgerald GA (1998) Increased F2-isoprostanes in Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for enhanced lipid peroxidation in vivo. FASEB J 12:1777–1783

Pratico D, Clark CM, Liun F, Lee VY-M, Trojanowski JQ (2002) Increase of brain oxidative stress in mild cognitive impairment. Arch Neurol 59:972–976

Prior R, D’Urso D, Frank R, Prikulis I, Pavloakovic G (1995) Experimental deposition of Alzheimer amyloid beta-protein in canine leptomeningeal vessels. NeuroReport 6:1747–1751

Prior R, D’Urso D, Frank R, Prikulis I, Wihl G, Pavlakovic G (1996a) Canine leptomeningeal organ culture: a new experimental model for cerebrovascular beta-amyloidosis. J Neurosci Meth 68:143–148

Prior R, D’Urso D, Frank R, Prikulis I, Pavlakovic G (1996b) Loss of vessel wall viability in cerebral amyloid angiopathy. NeuroReport 7:562

Pugliese M, Carrasco JL, Geloso MC, Mascort J, Michetti F, Mahy N (2004) Gamma-aminobutyric acidergic interneuron vulnerability to aging in canine prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci Res 77:913–920

Pugliese M, Geloso MC, Carrasco JL, Mascort J, Michetti F, Mahy N (2006) Canine cognitive deficit correlates with diffuse plaque maturation and S100beta (-) astrocytosis but not with insulin cerebrospinal fluid level. Acta Neuropathol 111:519–528

Pugliese M, Gangitano C, Ceccariglia S, Carrasco JL, Del Fa A, Rodriguez MJ, Michetti F, Mascort J, Mahy N (2007) Canine cognitive dysfunction and the cerebellum: acetylcholinesterase reduction, neuronal and glial changes. Brain Res 1139:85–94

Rao MS, Shetty AK (2004) Efficacy of doublecortin as a marker to analyse the absolute number and dendritic growth of newly generated neurons in the adult dentate gyrus. Eur J Neurosci 19:234–246

Rinaldi P, Polidori MC, Metastasio A, Mariani E, Mattioli P, Cherubini A, Catani M, Cecchetti R, Senin U, MEcocci P (2003) Plasma antioxdiants are similarly depleted in mild cognitive impairment and in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurbiol Aging 24:915–919

Rissman RA, De Blas AL, Armstrong DM (2007) GABA(A) receptors in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurochem 103:1285–1292

Rofina J, van Andel I, van Ederen AM, Papaioannou N, Yamaguchi H, Gruys E (2003) Canine counterpart of senile dementia of the Alzheimer type: amyloid plaques near capillaries but lack of spatial relationship with activated microglia and macrophages. Amyloid 10:86–96

Rofina JE, Singh K, Skoumalova-Vesela A, van Ederen AM, van Asten AJ, Wilhelm J, Gruys E (2004) Histochemical accumulation of oxidative damage products is associated with Alzheimer-like pathology in the canine. Amyloid 11:90–100

Rofina JE, van Ederen AM, Toussaint MJ, Secreve M, van der Spek A, van der Meer I, Van Eerdenburg FJ, Gruys E (2006) Cognitive disturbances in old dogs suffering from the canine counterpart of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Res 1069:216–226

Rohn TT, Head E (2008) Caspase activation in Alzheimer’s disease: early to rise and late to bed. Rev Neurosci 19:383–393

Satou T, Cummings BJ, Head E, Nielson KA, Hahn FF, Milgram NW, Velazquez P, Cribbs DH, Tenner AJ, Cotman CW (1997) The progression of beta-amyloid deposition in the frontal cortex of the aged canine. Brain Res 774:35–43

Schliebs R, Arendt T (2006) The significance of the cholinergic system in the brain during aging and in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neural Transm 113:1625–1644

Selkoe DJ, Bell DS, Podlisny MB, Price DL, Cork LC (1987) Conservation of brain amyloid proteins in aged mammals and humans with Alzheimer’s disease. Science 235:873–877

Shimada A, Kuwamura M, Akawkura T, Umemura T, Takada K, Ohama E, Itakura C (1992a) Topographic relationship between senile plaques and cerebrovascular amyloidosis in the brain of aged dogs. J Vet Med Sci 54:137–144

Shimada A, Kuwamura M, Awakura T, Umemura T, Itakura C (1992b) An immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study on age-related astrocytic gliosis in the central nervous system of dogs. J Vet Med Sci 54:29–36

Simic G, Kostovic I, Winblad B, Bogdanovic N (1997) Volume and number of neurons of the human hippocampal formation in normal aging and Alzheimer’s disease. J Comp Neurol 379:482–494

Siso S, Tort S, Aparici C, Perez L, Vidal E, Pumarola M (2003) Abnormal neuronal expression of the calcium-binding proteins, parvalbumin and calbindin D-28 k, in aged dogs. J Comp Pathol 128:9–14

Siwak-Tapp CT, Head E, Muggenburg BA, Milgram NW, Cotman CW (2007) Neurogenesis decreases with age in the canine hippocampus and correlates with cognitive function. Neurobiol Learn Mem 88:249–259

Siwak-Tapp CT, Head E, Muggenburg BA, Milgram NW, Cotman CW (2008) Region specific neuron loss in the aged canine hippocampus is reduced by enrichment. Neurobiol Aging 29:521–528

Skoumalova A, Rofina J, Schwippelova Z, Gruys E, Wilhelm J (2003a) The role of free radicals in canine counterpart of senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Exp Gerontol 38:711–719

Skoumalova A, Rofina J, Schwippelova Z, Gruys E, Wilhelm J (2003b) The role of free radicals in canine counterpart of senile dementia of the Alzheimer type. Exp Gerontol 38:711–719

Smith CD, Carney JM, Starke-Reed PE, Oliver CN, Stadtman ER, Floyd RA, Markesbery WR (1991) Excess brain protein oxidation and enzyme dysfunction in normal aging and in Alzheimer disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88:10540–10543

Smith MA, Sayre LM, Monnier VM, Perry G (1996) Oxidative posttranslational modifications in Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Chem Neuropathol 28:41–48

Smith MA, Rottkamp CA, Nunomura A, Raina AK, Perry G (2000) Oxidative stress in Alzheimer’s disease. Biochim Biophys Acta 1502:139–144

Stadtman ER (1992) Protein oxidation and aging. Science 257:1220–1224

Stadtman ER, Berlett BS (1997) Reactive oxygen-mediated protein oxidation in aging and disease. Chem Res Toxicol 10:485–494

Studzinski CM, Araujo JA, Milgram NW (2005) The canine model of human cognitive aging and dementia: pharmacological validity of the model for assessment of human cognitive-enhancing drugs. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 29:489–498

Su M-Y, Head E, Brooks WM, Wang Z, Muggenberg BA, Adam GE, Sutherland RJ, Cotman CW, Nalcioglu O (1998) MR imaging of anatomic and vascular characteristics in a canine model of human aging. Neurobiol Aging 19:479–485

Su MY, Tapp PD, Vu L, Chen YF, Chu Y, Muggenburg B, Chiou JY, Chen C, Wang J, Bracco C, Head E (2005) A longitudinal study of brain morphometrics using serial magnetic resonance imaging analysis in a canine model of aging. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 29:389–397

Swanson KS, Vester BM, Apanavicius CJ, Kirby NA, Schook LB (2009) Implications of age and diet on canine cerebral cortex transcription. Neurobiol Aging 30(8):1314–1326

Tapp PD, Siwak CT, Gao FQ, Chiou JY, Black SE, Head E, Muggenburg BA, Cotman CW, Milgram NW, Su MY (2004) Frontal lobe volume, function, and beta-amyloid pathology in a canine model of aging. J Neurosci 24:8205–8213

Tapp PD, Head K, Head E, Milgram NW, Muggenburg BA, Su MY (2006) Application of an automated voxel-based morphometry technique to assess regional gray and white matter brain atrophy in a canine model of aging. Neuroimage 29:234–244

Thal DR, Rub U, Orantes M, Braak H (2002) Phases of A beta-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology 58:1791–1800

Torp R, Head E, Cotman CW (2000a) Ultrastructural analyses of beta-amyloid in the aged dog brain: neuronal beta-amyloid is localized to the plasma membrane. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 24:801–810

Torp R, Head E, Milgram NW, Hahn F, Ottersen OP, Cotman CW (2000b) Ultrastructural evidence of fibrillar b-amyloid associated with neuronal membranes in behaviorally characterized aged dog brains. Neuroscience 93:495–506

Torp R, Ottersen OP, Cotman CW, Head E (2003) Identification of neuronal plasma membrane microdomains that colocalize beta-amyloid and presenilin: implications for beta-amyloid precursor protein processing. Neuroscience 120:291–300

Uchida K, Miyauchi Y, Nakayama H, Goto N (1990) Amyloid angiopathy with cerebral hemorrhage and senile plaque in aged dogs. Nippon Juigaku Zasshi 52:605–611

Uchida K, Nakayama H, Goto N (1991) Pathological studies on cerebral amyloid angiopathy, senile plaques and amyloid deposition in visceral organs in aged dogs. J Vet Med Sci 53:1037–1042

Uchida K, Tani Y, Uetsuka K, Nakayama H, Goto N (1992) Immunohistochemical studies on canine cerebral amyloid angiopathy and senile plaques. J Vet Med Sci 54:659–667

Uchida K, Okuda R, Yamaguchi R, Tateyama S, Nakayama H, Goto N (1993) Double-labeling immunohistochemical studies on canine senile plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. J Vet Med Sci 55:637–642

Uchida K, Kuroki K, Yoshino T, Yamaguchi R, Tateyama S (1997) Immunohistochemical study of constituents other than beta-protein in canine senile plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Acta Neuropathol 93:277–284

van Praag H, Schinder AF, Christie BR, Toni N, Palmer TD, Gage FH (2002) Functional neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. Nature 416:1030–1034

Walker LC (1997) Animal models of cerebral beta-amyloid angiopathy. Brain Res Rev 25:70–84

Weindruch R, Kayo T, Lee CK, Prolla TA (2002) Gene expression profiling of aging using DNA microarrays. Mech Ageing Dev 123:177–193

West MJ (1993) Regionally specific loss of neurons in the aging human hippocampus. Neurobiol Aging 14:287–293

West MJ, Kawas CH, Martin LJ, Troncoso JC (2000) The CA1 region of the human hippocampus is a hot spot in Alzheimer’s disease. Ann NY Acad Sci 908:255–259

Westerman MA, Cooper-Blacketer D, Mariash A, Kotilinek L, Kawarabayashi T, Younkin LH, Carlson GA, Younkin SG, Ashe KH (2002) The relationship between Ab and memory in the Tg2576 mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci 22:1858–1867

Wisniewski HM, Johnson AB, Raine CS, Kay WJ, Terry RD (1970) Senile plaques and cerebral amyloidosis in aged dogs. Lab Invest 23:287–296

Wisniewski HM, Wegiel J, Morys J, Bancher C, Soltysiak Z, Kim KS (1990) Aged dogs: an animal model to study beta-protein amyloidogenesis. In: Maurer PRK, Beckman H (eds) Alzheimer’s disease. epidemiology, neuropathology, neurochemistry and clinics. Springer, New York, pp 151–167

Wisniewski T, Lalowski M, Bobik M, Russell M, Strosznajder J, Frangione B (1996) Amyloid Beta 1–42 deposits do not lead to Alzheimer’s neuritic plaques in aged dogs. Biochem J 313:575–580

Yoshino T, Uchida K, Tateyama S, Yamaguchi R, Nakayama H, Goto N (1996) A retrospective study of canine senile plaques and cerebral amyloid angiopathy. Vet Pathol 33:230–234

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

About this article

Cite this article

Head, E. Neurobiology of the aging dog. AGE 33, 485–496 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-010-9183-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11357-010-9183-3