Abstract

Polypyrrole (PPy) conducting films, doped with 4-amino-3-hydroxynaphthalene sulfonic acid (AHNSA), were electrosynthesized by anodic oxidation of pyrrole on Pt and steel electrodes in aqueous medium (0.01 M AHNSA +0.007 M NaOH, using cyclic voltammetry (CV), and their electrochemical properties were studied. Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy confirmed the formation of AHNSA-PPy films. Their morphology was characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and their optical properties, including UV-VIS absorption and fluorescence spectra, were also investigated. AHNSA-PPy films were used for the removal of chromium(VI) from aqueous solution, by means of the immersion method and the Cr(VI) electro-reduction method. The effect of various experimental parameters, including the adsorbent (polymer) mass, pH, type of electrodes, and current intensity, on the adsorption of chromium by the polymer was performed and optimized. The adsorption and electro-reduction of (Cr VI) on the AHNSA-PPy film surface were found to be highly pH-dependent, and the kinetics of Cr(VI) adsorption and electro-reduction followed second-order kinetic curves. Apparent second-order rate constants were about three times higher for the Cr(VI) electro-reduction method than for the immersion method, indicating that the use of electro-reduction method significantly accelerated the chromium adsorption process on polymer. The maximum adsorption capacity of the AHNSA-PPy film for chromium was 224 mg g−1. A 96% chromium removal from pure aqueous solution was reached within about 48 h by the immersion method, but only within about 6 h by the Cr(VI) electro-reduction method. Application of both methods to Cr(VI) fortified natural waters of Senegal led to chromium removal efficiency high values (93 to 96% according to the type of natural water).

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Because of their remarkable physicochemical and electrochemical properties, the conducting organic polymers (COPs) have opened very interesting perspectives in the field of new materials and modified electrodes. Due to their outstanding mechanical properties, resistance to corrosion, and low production cost, COPs have been able to complement and, in some cases, to replace metallic materials. They offer several important applications, such as energy storage (Yang et al. 2015; Saranya et al. 2015; Noël and Randriamahazaka 2012), protection against corrosion (Diaw et al. 2008; Flamini and Saidman 2010; Armelin et al. 2008; Porebska et al. 2005; Kowalski et al. 2007; Sheng et al. 2014; Lei et al., 2014a, b; González and Saidman 2012), and electronic components in various devices (Ke et al. 2015; Tsai 2007; Lange et al. 2008).

In recent years, COPs, and polymer nanocomposites and nanotubes have been widely used for the treatment of polluted waters (Setshedi et al. 2013; Omraei et al. 2011; Gupta and Suhas 2009; Riaz and Ashraf 2011; Pickup et al. 1998; Khan et al. 2011) and the removal of various heavy metal ions, such as chromium, cadmium, lead, and mercury, from aqueous solutions and waste waters (Wang et al. 2014; Kumar et al. 2008; Krishnani et al. 2013; Bhaumik et al. 2012; Ansari and Fahim 2007; Ghorbani and Eisazadeh 2012; Denizli et al. 2002; Gupta et al. 2004; Mansour et al. 2011).

Chromium is one of the most toxic heavy metals, especially under its hexavalent Cr(VI) form. Indeed, Cr(VI) is highly carcinogenic and can lead to the development of skin lesions, liver damages, and respiratory diseases (Xie et al. 2005; Poey and Philibert 2000). Moreover, chromium and other heavy metals present an acute toxicity for fry in contaminated water (Krishnani et al. 2003).

Two major strategies have been recently developed in the field of the treatment of waters containing heavy metals:

The first strategy consists to synthesize, generally by organic reactions, monomers functionalized with chelating groups, then to perform electropolymerization. For instance, Heitzmann et al. (2007a, b) have fixed chelating groups, including EDTA or malonic acid, on pyrrole, and used the corresponding electro-synthesized polymer for the electrochemical detection and elimination of metal cations. In their work, they have synthesized 3-(pyrrol-1-yl)propyl-malonic acid and N,N-ethylene bis [N-[(3-(pyrrol-1-yl)propyl)carbamoyl)methyl]glycine] that were electropolymerized by cyclic voltammetry. The obtained polymers showed a good capacity for fixing metal cations such as Cd(II), Cu(II), and Pb(II).

Similarly, El-Sherif et al. (2013) have chemically synthesized pyrrole-N-propyl acid and then have grafted cysteine on the corresponding electrosynthesized polymer. They have obtained cysteine-modified polymer nanofibers, which were applied to the rapid and efficient removal of Cr(III) from tannery waste water samples.

The second strategy is based on the functionalizing or doping of the polymer chain with a chelating salt, in order to remove heavy metal ions.

For example, Ballav et al. (2012) have utilized a glycine-doped polypyrrole film to remove Cr(VI). Also, Tian et al. (2012) and Tian and Yang (2007) have electrochemically synthesized polypyrrole films doped with sodium toluene sulfonate (PTS), which were applied to the electroreduction of Cr(VI) under potentiostatic and potentiodynamic conditions.

Moreover, Wanekaya and Sadik (2002) have developed an electrochemical method for the determination of lead by using an over-oxidized polypyrrole (OPPy) electrode, doped with 2(2-pyridylazo) chromotropic acid anion (PACh2−). PACh2− was found to act both as a chelating agent and a counter-anion within the polypyrrole matrix, and Pb2+ was accumulated on the solid electrode via the formation of a lead–PACh complex.

Also, Zanganeh and Amini (2008) have used a modified polypyrrole electrode, prepared by pyrrole electropolymerization in the presence of an anionic complexing ligand, namely [2-hydroxy-1-(1-hydroxy-2-naphthylazo)-naphthalene-4-sulfonic acid sodium] salt, for the selective detection of Cu2+ ions (concentration range = 5 × 10−8–1 × 10−2 M) in aqueous solution.

All these results demonstrated the great interest of developing novel electrochemical methods, based on COPs, for the determination and removal of toxic heavy metals from aqueous solutions and other media. However, until now, polymers applied to the treatment of wastewaters, polluted with heavy metals, were mostly obtained by chemical synthesis, which generally required a complex and time-consuming process, resulting into the formation of impure and insoluble products, and requesting difficult investigation on the impact of adsorbed heavy metal ions on the polymer properties (Bhaumik et al. 2012; Ansari and Fahim. 2007; Ghorbani and Eisazadeh 2012; Denizli et al. 2002; Gupta et al. 2004; Mansour et al. 2011). In the present study, we selected, 4-amino-3-hydroxynaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (AHNSA, chemical structure in Scheme 1), recently utilized for the fluorescent sensing of CN− in water (Shi et al. 2013), as a functionalized salt to electropolymerize and dope pyrrole, in order to obtain an efficient trap of heavy metal ions such as chromium ions. We reported the electro-synthesis and characterization of AHNSA-doped polypyrrole (AHNSA-PPy) films and their application to the removal of Cr(VI) from aqueous solutions. We compared the performances of two chromium removal methods, including the immersion method and the electro-reduction method, and we applied both methods to the removal of Cr(VI) from fortified natural waters.

Experimental

Chemicals and preparation of solutions

Pyrrole (Py 99%), 4-amino-3-hydroxynaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (AHNSA), sodium hydroxide (NaOH), dimethylformamide (DMF), and potassium dichromate (K2Cr2O7) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received.

The aqueous medium used for Py electropolymerization was constituted of 0.01 M AHNSA +0.007 M NaOH. To increase the solubility of poorly hydro-soluble AHNSA, this mixture was stirred in an ultrasound bath for 5 min. Finally, a clear solution of pH = 5.1 was obtained, and an amount of Py corresponding to a 0.1 M concentration was added.

Electrochemical measurements

All electrochemical measurements were performed in a single compartment three-electrode cell using an EG&G Princeton Applied Research Model potentiostat/galavanostat, equipped with a Kipp & Zonen X-Y recorder for electrochemical studies, and a Hameg Triple Power Supply Model HMB 7042–5 for chromium electro-reduction process. A Pt disk (diameter = 5 mm) and/or a Pt-coated glass plate was used as working electrode, whereas a saturated calomel electrode (SCE) and a stainless grid were utilized, respectively, as reference electrode and counter electrode. The electropolymerization of Py was performed anodically by cyclic voltammetry (−0.8–1.0 V/SCE).

Spectral measurements

Fourier transform-infra red (FT-IR) absorption spectra were obtained on a Magna-IR 860 FT-IR spectrometer (Nicolet Instrument Corp., Madison, WI), at a 2 cm−1 spectral resolution. FT-IR spectra of the monomers (Py and AHNSA) were recorded in pressed KBr pellets, using a standard DTGS detector, by collecting 50 scans. The spectra of the corresponding polymer films (AHNSA-PPy) were analyzed on Pt-coated glass plates by infrared-reflexion absorption spectroscopy (IR-RAS), with a 30° incidence angle accessory. All spectra were baseline corrected, using OMNIC internal software, and were unsmoothed.

Ultraviolet–visible (UV–VIS) absorption spectra of Py, AHNSA, and AHNSA-PPy were recorded with a Lambda 10 Perkin-Elmer UV–VIS absorption spectrometer in DMF solution and/or in the solid state on indium tin oxide (ITO) plates. The fluorescence excitation and emission spectra of AHNSA, Py, and AHNSA-PPy were obtained in DMF solutions, using a Kontron SFM-25 spectrofluorimeter, interfaced with a microcomputer.

The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) photos of AHNSA-PPy films were obtained on a S 440 model Leica instrument equipped with a tungsten filament, using a four sector detector for secondary and retro-diffused electrons.

The chromium concentrations in aqueous solution were analyzed by means of a Perkin-Elmer Optima 8300 inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometer (ICP-OES). The natural water samples were analyzed after filtration through 0.7-μm glass fiber filters.

Procedures for the determination of chromium removal

A modified steel plate covered with AHNSA-PPy film was immersed in an aqueous solution of 50 mg L−1 K2Cr2O7 (corresponding to a chromium (VI) concentration of 18 mg L−1), and the evolution of the chromium (VI) 350-nm and 260-nm UV-VIS absorption bands was followed in function of the polymer impregnation time, medium pH, and polymer mass.

The effect of chromic solution pH changes on the polymer adsorption capacity was examined between pH values of 1.0 and 12.0 by measuring the Cr(VI) solution UV-VIS absorbance. The solution pH values were adjusted by adding small amounts of H2SO4 or HNO3. The final metal concentrations were determined by applying the Beer-Lambert law.

The Cr(VI) removal efficiency (% R) of the polymer was estimated as a function of Cr(VI) concentration using Eq. (1):

where C 0 and C t are, respectively, the concentrations (mg L−1) of Cr(VI) at times t = 0 and t.

The adsorption capacity of the polymer at the time t (q t ) was calculated by means of Eq. (2):

where C 0 and C t are, respectively, the Cr(VI) concentrations (mg L−1) at times t = 0 and t, m = polymer mass (g), V = potassium dichromate solution volume (L).

For the application to natural waters, the different aqueous samples under study were first filtered using 0.7-μm glass fiber filters. Then, the filtered samples were fortified by dissolving 50 mg of potassium dichromate in a 1-L volume of these samples, to reach an initial concentration = 50 mg L−1 and adjusted at the optimum pH value.

Results and discussion

Electrosynthesis and electrochemical properties of AHNSA-PPy

Electropolymerization

Firstly, electropolymerization was performed by cyclic voltammetry (CV) in an aqueous medium containing 0.01 M AHNSA +7.10−3 M NaOH +0.1 M Py. Under these conditions, upon repetitively scanning the potential between −0.8 and 1.0 V/SCE at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1, we were able to obtain adherent, thin, electroactive, blackish PPy films on Pt electrode. After the first scan, the CV curves presented three anodic and three cathodic peaks, respectively, located at −0.3, 0.0, and 0.7 V/SCE and at −0.1, −0.3, and −0.6 V/SCE (Fig. 1). These anodic and cathodic peaks were attributed, respectively, to the PPy oxidation and reduction processes. The intensity of these peaks steadily increased with the number of cycles, which indicated a gradual growth of the polymer film on the electrode surface.

In order to confirm this assignation, we also recorded the voltammograms of an aqueous solution containing only 0.01 M AHNSA +7.10−3 M NaOH without Py, upon scanning the potential between −0.8 and 1.0 V/SCE during 10 cycles. The corresponding CV curves exhibited only two anodic and cathodic peaks, appearing, respectively, at −0.2 and +0.65 V/SCE, and at −0.35 and −0.7 V/SCE that we attributed to the oxidation and reduction processes of AHNSA. Under these conditions, no film was deposited on the Pt electrode, and the peak intensity decreased with the number of cycles. These electrochemical features indicated that there was no electropolymerization of AHNSA, which suggested that the formed PPy film was doped (or functionalized) with AHNSA.

Electro-activity and stability of AHNSA-PPy films

The electrochemical behavior of AHNSA-PPy films, electrodeposited on Pt by CV (20 cycles), was investigated in 0.01 M AHNSA +0.007 M NaOH monomer-free aqueous solutions, upon scanning the potential between −0.8 and 1.0 V/SCE.

The voltammograms recorded in these conditions presented three well-defined anodic and cathodic peaks, respectively, located at about −0.3, 0.0, and 0.7 V/SCE, and −0.1, −0.3, and −0.5 V/SCE, which suggests that the polymer film under study was electro-active and that its doping and undoping processes took place in a well-organized polymeric system (Fig.2).

Electro-activity of an AHNSA-PPy film in a 0.01 M AHNSA +0.007 M NaOH monomer-free aqueous solution. Voltammograms were performed at various scan rates v = 100 (a), 20 (b), 50 (c), and 100 mV s−1 (d). In insert: linear variation of the AHNSA-doped polypyrrole current density of anodic and cathodic peaks (at 0.7 and −0.5 V/SCE) with the scan rate

As seen in the insert of Fig. 2, the current density (J) values of the anodic and cathodic peaks varied linearly with the scan rate (v) in the range 10–100 mV s−1, which indicates that the PPy redox processes were controlled by reactions of surface-localized electroactive species on the film-covered Pt electrode, a behavior generally observed for conducting polymers (Dahlgren et al. 2000; Fouad et al. 2004; Lô et al. 2006; Diaw et al. 2013).

To investigate the electrochemical stability of these films, we submitted them to 50 successive redox cycles. We found that the films presented a loss of electro-activity of only about 13% after 14 cycles. For a larger number of cycles, there was practically no additional decrease of the current density value. These results indicate a rather satisfactory electrochemical stability of AHNSA-PPy films prepared in aqueous solutions.

Characterization of the AHNSA-PPy films

In order to characterize the molecular structure and type of coupling of the AHNSA-PPy films, we recorded the FT-IR spectra of monomers (Py and AHNSA), and we compared them to the AHNSA-PPy polymer spectrum. We also studied the morphology of these films by means of scanning electron microscopy (SEM).

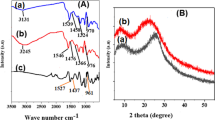

FT-IR spectroscopic analysis

We investigated the FT-IR spectra of Py and of AHNSA in KBr pellets, and those of the oxidized AHNSA-PPy films, obtained by CV (20 cycles) on ITO plates in the above-described aqueous medium. All FT-IR spectroscopic data, including the vibration wavenumbers, relative intensities and assignments of the main IR bands, are given in Table 1. The assignment of the main IR bands of Py and of AHNSA-PPy was performed by comparing our IR results with those described in the case of several analogous compounds (Fall et al. 2001; Johans et al. 2002; Just et al. 1999, 2001; Socrates 2004; Lu et al. 2009).

We essentially focused our IR study on the bands located in the 600–2000 cm−1 region, in which most spectral changes occurring upon electropolymerization of pyrrole were generally observed. The partial IR spectra (600–2000 cm−1 region) of Py, AHNSA, and AHNSA-PPy oxidized film are presented in Fig. 3.

The Py FT-IR spectrum (Fig. 3a and Table 1) was rather complex in this region, because it contained the heterocyclic ring C-H, C-C, and C = C in-plane (ip) and out-of-plane (oop) bending and stretching vibrations, corresponding to the usual features of Py. It appeared nine strong or very strong bands at 730, 1015, 1050, 1070, 1425, 1528, and 1680 cm−1, and also some weak or very weak bands at 800, 867, 1150, 1279, 1472, and 1570 cm−1. The very strong band observed at 730 cm−1 can be attributed to the γC-H oop bending vibrations of Py ring four adjacent hydrogens.

The strong or very strong bands located at 1015, 1050, and 1070 cm−1 were ascribed to the γC-H oop bending vibrations of two hydrogens in α-position of the Py ring. Moreover, several bands occurring in the 1200–1300 and 1425–1570 cm−1 regions were assigned, respectively, to the νC-N stretching vibrations of the pyrrolyl group and to the νC = C stretching vibrations of the Py ring.

On the other hand, the AHNSA IR spectrum (Fig. 3b) exhibited five weak or medium bands appearing at 712, 750, 770, 890, and 940 cm−1, attributed to γC-H bending vibrations of the naphthalene cycle un-substituted and tri-substituted phenyl groups. Also, two strong and very strong bands, located at 1035 and 1170 cm−1, can be assigned to the symmetric and asymmetric νS-O stretching vibrations of the SO3H substituent. Two other bands, occurring at 1220 cm−1 (strong) and 1283 cm−1 (weak), corresponded, respectively, to the naphthol and naphthylamine C-O and C-N stretching vibrations. Also, one strong band, appearing at about 1565 cm−1, was assigned to the naphthalene cycle νC = C stretching vibrations. Moreover, we noted the presence of bands at 3250 and 3350 cm−1, characteristic, respectively, of the νN-H and νO-H stretching vibrations of NH2 and OH substituents.

The IR spectrum of AHNSA-PPy film, electrosynthesized in the above-described aqueous medium by CV (20 cycles), was also compared to the spectra of Py and AHNSA (Table 1 and Fig. 3c). We observed several important spectral changes relative to the Py spectrum, especially in the 600–2000 cm−1 region, due to the couplings which occurred during the electropolymerization reaction. The main important change was that the monomer very strong band at 730 cm−1 attributed to the γC-H oop bending vibrations of the Py ring four adjacent hydrogens, completely vanished in the polymer spectrum, which indicated that the Py rings underwent coupling reactions during the electropolymerization process. Another notable point was that the monomer bands located at 1015, 1050, and 1070 cm−1, ascribed to the γC-H bending vibrations of two hydrogen atoms in α-position of Py ring, disappeared entirely in the AHNSA-PPy spectrum, which confirmed that, as expected, the coupling took place in the α-positions of the Py rings during the electropolymerization reaction. Moreover, it appeared simultaneously in the polymer spectrum a new, very strong band occurring at 925 cm−1, probably due to the oop γC-H vibrations of two adjacent hydrogens in 2,5-disubstituted Py ring(s).

In contrast, there was no important modification between the AHNSA and the AHNSA-PPy IR spectra, in the position of the weak or medium bands, characteristic of the γC-H oop bending vibrations of the naphthalene cycle un-substituted and tri-substituted phenyl groups, which appeared at 712, 770, and 940 cm−1 (shoulder) in the polymer spectrum. This suggests that no significant change took place in the degree of substitution of the AHNSA naphthalene cycle which, therefore, was not involved in the electropolymerization process and that AHNSA, under its amphoteric salt form, doped the polymer chain. In addition, it occurred two bands, located at about 1565 and 1700 cm−1, that were assigned to the νC = C stretching vibrations of the naphthalene cycle, and two strong bands appearing at 3400 and 3235 cm−1, respectively, due to the νN-H and νO-H stretching vibrations of the naphthalene cycle hydrogen-bonded NH2 and OH substituents.

Film morphology

The morphology of oxidized AHNSA-PPy films, electrodeposited by CV (20 cycles) on ITO plates in 0.01 M AHNSA +0.007 M NaOH aqueous solution, was studied by scanning electron microscopy (SEM). The SEM micrographs presented in Fig.4a, b were obtained, respectively, before and after Cr(VI) adsorption. Figure 4a shows that the AHNSA-PPy films in the oxidized state presented a relatively homogeneous, but rough surface, with fairly regular and ordered grits. Moreover, the film width values ranged between about 34.5 and 46.5 μm. This SEM photo also indicates that the AHNSA-PPy films had a shape similar to those of PPy films doped with sodium para-toluene sulfonate and used for the electroreduction of Cr(VI) by Tian et al. (2012). In Fig. 4b, realized after Cr(VI) adsorption, it can be seen that the AHNSA-PPy film exhibited a less homogeneous and less regular surface, which indicated the probable existence of ionic interactions between Cr(VI) and various sites of AHNSA-PPy, as confirmed below in our study on the effect of chromium adsorption on the polymer FT-IR spectra.

Optical properties of the AHNSA-PPy films

UV-VIS electronic absorption spectra

In order to assign the AHNSA-PPy polymer absorption spectrum bands, we studied in parallel the experimental UV-VIS absorption spectral properties of the monomers (Py and AHNSA) and of the polymer in DMF diluted solution at room temperature (Fig. 5 and Table 2). For this purpose, the UV-VIS absorption spectra of Py, AHNSA and of the oxidized polymer were compared with previous papers concerning the UV-VIS absorption spectral data of Py derivatives, substituted naphthalenes, and the corresponding polymers (Shi et al. 2013, Bhandari et al. 2011; Banjoko et al. 2009; Ozser et al. 2013; Armarego 1971).

The Py spectrum presented two relatively narrow, well-resolved, intense main absorption bands at around 212 and 265 nm (Fig. 5 and Table 2). The shortest-wavelength band, which possessed the highest molar absorption coefficient (ε) value (log ε max = 4.17), and the longest-wavelength band with a smaller ε value (log ε = 3.84), were ascribed to the π → π* electronic transitions of the Py ring. It is worthwhile to note that our spectral results were very close to those obtained by Armarego (1971) for Py in ethanol.

The AHNSA spectrum (c = 1 × 10−5 M) possessed a strong, relatively wide band with a maximum at about 265 nm (log ε max = 4.01), and weaker bands at around 305 nm (log ε = 3.72), 350 (log ε = 3.62), and 390 nm (log ε = 3.60) (Fig. 5 and Table 2). The intense, shortest-wavelength band was attributed to π-π* electronic transitions of the naphthalene cycle, whereas the other, weaker bands were probably due to much less intense n-π* electronic transitions of the SO3H, OH, and NH2 substituents.

In the AHNSA-PPy UV-VIS absorption spectrum, recorded in DMF solution (c = 3.4 × 10−5 r.u. L−1), we observed the presence of two rather close, strong shorter-wavelength peaks at 255 (log ε = 3.94) and 285 nm (log ε max = 4.10), and much weaker bands located at about 320 (log ε = 3.60), 345 (log ε = 3.35), 370 (log ε = 3.26), and a wide, weak band at around 410–450 nm (log ε = 3.14). Overall, the shape of the polymer absorption spectrum was comparable to that of Py, with slightly wider bands, and the shortest-wavelength strong peaks were significantly red shifted relative to the Py corresponding bands (Δλ = 20–43 nm). These shortest-wavelength strong bands were attributed to the π → π* electronic transitions of the Py ring, resulting from the AHNSA-PPy conjugated heteroaromatic system, whereas the weaker bands, occurring at wavelengths comparable to those of AHNSA, probably corresponded to the less intense n-π* electronic transitions of the naphthalene SO3H, OH, and NH2 substituents. These spectral features confirmed the formation of PPy chains and also demonstrated the insertion of AHNSA under the form of amphoteric salt between the PPy chains.

Fluorescence spectra

The fluorescence excitation and emission spectra of AHNSA and of the AHNSA-PPy polymer oxidized films (obtained by CV - 5 cycles) were recorded in diluted DMF solutions at room temperature, and, for the polymer, in the solid state on ITO (Table 3 and Fig. 6). Py was practically not fluorescent.

The fluorescence excitation spectrum of AHNSA possessed one broad main band with a maximum located at 345 nm, and a shoulder at around 300 nm, whereas its fluorescence emission spectrum was characterized by one relatively wide band appearing at about 430 nm (Fig. 6). In the case of the AHNSA-PPy polymer, the fluorescence excitation spectrum displayed a main, broad band, with a maximum occurring at about 335 nm and a secondary peak at around 290 nm, whereas the fluorescence emission spectrum presented only one very broad band, located at around 406 nm (Fig. 6). The relatively moderate blue shifts observed for the excitation spectra (Δλ ex = −10 nm) as well for the emission spectra (Δλ em = − 24 nm), when passing from AHNSA (monomer) to the AHNSA-PPy polymer, indicated the existence of interactions between the polypyrrolic chains and AHNSA molecules and confirmed that the naphthalene derivative (responsible of the fluorescence) was not involved in the electropolymerization reaction but was simply inserted between the polypyrrolic chains. Moreover, these rather moderate blue shifts indicated the existence of notable intermolecular interactions between AHNSA, under the form of amphoteric salt, and the polypyrrolic chains. For AHNSA as well as for the polymer, the excitation maxima occurred at wavelength values relatively close to those of the corresponding absorption maxima ones, which suggested that the excited fluorescent species can be considered as identical to the absorbing ones (Table 3).

The solid-state fluorescence excitation and emission spectra of AHNSA-PPy polymer were also obtained for films in the oxidized form, electrodeposited on ITO plates (Table 3). The fluorescence excitation spectrum possessed only one strong band with a maximum located at 310 nm, while the fluorescence emission spectrum presented also one strong peak at around 375 nm (Table 3). Therefore, the AHNSA-PPy fluorescence excitation and emission maxima underwent significant blue shifts relative to the polymer spectra recorded in DMF (Δλ = −20 - –25 nm). These blue shifts suggested that the polymer conformations should be less planar and probably less ordered in the solid state than in solution, with different intermolecular interactions between AHNSA molecules and PPy chains in the solid state and in solution. This unusual behavior, in contrast with our previous results concerning the UV-VIS absorption spectra of substituted poly(N-phenylpyrrole)s in solution and in the solid-state (Diaw et al. 2015), confirmed the very peculiar structure of the AHNSA-PPy polymer, containing AHNSA units very probably inserted between the polypyrrolic chains.

Use of the AHNSA-PPy polymer films for the removal and electro-reduction of chromium (VI)

In this section, we used the above-prepared and characterized AHNSA-PPy polymer for the removal and electro-reduction of chromium (VI) in aqueous solutions.

Optimization of experimental conditions

Polymer mass optimization

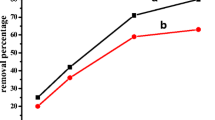

In order to optimize the AHNSA-PPy polymer mass (m) deposited on steel plates, necessary to remove chromium, we immersed steel plates covered with different polymer masses (m 1 = 12.8 mg, m 2 = 15.5 mg, m 3 = 25.6 mg, m 4 = 31 mg) in a Cr(VI) (concentration = 18 mg L−1) pH 2 aqueous solution, and we monitored the evolution of the chromium UV-VIS absorbance at 350 nm as function of time. As seen in Fig. 7, all curves presented an exponential decrease, followed by a plateau region, for which the quasi-totality of Cr(VI) was adsorbed. The Cr(VI) removal rate increased significantly with the polymer mass covering the steel plate. The maximum Cr(VI) removal rate was attained for a polymer mass m 4 = 31 mg, which was considered as the optimal polymer mass, corresponding to about 95% of Cr(VI) adsorbed by the polymer within 24 h.

pH effect optimization

The potassium dichromate aqueous solution pH has a considerable impact on the Cr(VI) adsorption process onto the polymer surface, since it controls the speciation of the chromium ion species and the adsorbent surface charge. According to the concentration and solution pH, Cr(VI) is occurring under three different oxyanionic forms, including predominantly Cr2O7 2− at pH < 2, HCrO4 − between pH 2 and 6, and CrO4 2− above pH 6 (Förstner and Wittmann 1981; Bhaumik et al. 2012). In order to optimize the pH value for maximum removal efficiency of Cr(VI), we investigated the pH effect on the polymer surface capacity to adsorb Cr(VI), after 48 h. By varying these pH values between 1 and 12, we found that the Cr(VI) removal efficiency strongly decreased when increasing the dichromate solution pH toward alkaline values (Fig. 8). As can be seen, the Cr(VI) removal efficiency exhibited higher values for a very acid medium, and the maximum Cr(VI) removal percentage (95.0%), corresponding to the maximum polymer capacity to adsorb Cr(VI) ions, was obtained for a dichromate solution optimal pH value = 2. Similar Cr(VI) removal percentage vs. pH curves were reported by Deng and Bai (2004) and by Bhaumik et al. (2012), respectively, for the Cr(VI) adsorption on aminated polyacrylonitrile fibers and on PPy-polyaniline nanofibers.

Moreover, we studied the solution pH effect on the Cr(VI) electrochemical reduction, and we found that, like in the case of the polymer adsorption process of Cr(VI) ions, the electrochemical reduction was very much improved in a pH = 1–2 medium but strongly decreased in alkaline media, after 6 h. The shape of the curve of the chromium (VI) electrochemical reduction efficiency vs. pH was very similar to the curve of Fig. 8. Indeed, approximately 94% of Cr(VI) electrochemical reduction was measured in this very acidic medium region. Therefore, we chose the same optimal pH value of 2 for the Cr(VI) electrochemical reduction process.

Optimization of electrodes and Cr(VI) electro-reduction

To optimize the type of electrodes, we introduced, in a pH = 2 potassium dichromate (50 mg L−1) solution, various steel plates, including either two naked plates, one polymer-covered anode and one naked cathodic plate, one polymer-covered cathode and one naked anodic plate, or two polymer-covered anode and cathode plate. Then, by applying a potential of −0.8 V, we followed during 2 h the evolution of the electrochemical reduction of Cr(VI). This electro-reduction was materialized by a gradual discoloration of the potassium dichromate solution during this process. We also determined the Cr(VI) removal efficiency (R, in %) during electro-reduction, using the various above-described steel plates (Table 4). As can be seen, the R value depended on the nature of electrodes used as cathode or anode. We found that the electro-reduction process was the most efficient and led to the R maximum value (94%) by using a naked plate as cathode (+), coupled with a polymer-covered plate as anode (−). Therefore, the later electrode system was considered as the optimized one.

Optimization of the current intensity effect on the Cr(VI) electro-reduction

We also optimized the electrical current intensity (I) effect on the Cr(VI) electro-reduction process, using the polymer-covered electrode (Table 5). This table showed an important increase of the % of R when augmenting the current value from 1 to 10 mA, with a maximum R value (94%) for I = 5 mA. But, for I values >10 mA, a decrease of the R percentage value was observed. The later phenomenon can be explained by an over-oxidation of the polymer for too high current intensity values, which led to a polymer film degradation. Therefore, we chose an optimized value of I = 5 mA.

Taking into account these optimized results, we performed our environmental studies on the removal and electro-reduction of chromium in the following experimental conditions: use of a polymer mass of 31 mg and a pH = 2 potassium dichromate aqueous solution, with a polymer-covered plate as negative electrode and a bare plate as positive electrode, and an applied current value of 5 mA.

Kinetic study of the Cr(VI) removal using the immersion method

AHNSA-PPy polymer films were synthesized by CV (20 cycles) on steel plates, which were dived in pH 2 K2Cr2O7 (50 mg L−1) aqueous solutions. Then, the evolution of the Cr(VI) solution UV-visible absorption spectra was followed as function of the polymer impregnation time. Using a polymer-covered anode (m = 31 mg) in optimized experimental conditions, we observed a progressive decrease of the chromium absorption bands located at 260 and 350 nm with time, accompanied by a gradual discoloration of the solution, which indicated that the chromium concentration in solution significantly diminished with time (Fig. 9). UV-VIS absorption spectrometry demonstrated that about 96% of chromium was removed after a polymer impregnation time of 48 h.

As seen in Fig. 10a, the decay kinetic curve of chromium adsorption on the polymer-covered anode (Cr(VI) 350-nm band absorbance vs. time) was clearly exponential, the absorbance decrease being explained by the formation of a non-absorbing complex between the polymer and the metal. The analysis of the kinetic of chromium adsorption on polymer led to a second-order kinetic curve, since the curve 1/Ct-1/C0 as function of time was strictly linear: y = 0.46 t with a correlation coefficient r 2 = 0.999 (Fig. 10b). Therefore, we obtained a rate constant value k 2 = 0.46 L mol−1 s−1.

Using Eq. (2), we also calculated the adsorption capacity of the AHNSA-PPy polymer (q t , mg g−1), corresponding to the quantity of chromium adsorbed by gram of polymer. We followed, by UV-VIS absorption spectrometry, the evolution of the adsorbed chromium quantity with the impregnation time. It is worthwhile to note that the adsorbed quantity of metal significantly increased with the polymer impregnation time and then reached a plateau region. As seen in Fig. 11, about 224 mg of chromium was adsorbed per gram of polymer, after an impregnation time of approximately 48 h.

ICP-OES analysis of chromium

Furthermore, we monitored the evolution of Cr(VI) concentration in potassium dichromate solution (initial concentration = 6.0 mg L−1) by means of the inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) method. We observed a progressive decrease of Cr(VI) concentration from 6.0 to 0.5 mg L−1 with the polymer impregnation time (Fig. 12). Therefore, the ICP-OES method showed that about 92% of chromium was removed after a polymer impregnation time of 48 h, a percentage close to the removal of about 96% of chromium, determined during the same time by UV-VIS absorption spectrometry. These interesting ICP-OES results confirmed that the AHNSA-PPy polymer was able to remove the quasi-totality of chromium from diluted potassium dichromate aqueous solutions.

Influence of the chromium adsorption on the polymer FT-IR spectrum

We compared the FT-IR absorption spectra of the AHNSA-PPy polymer, before and after immersion in a pH 2 potassium dichromate solution (concentration = 50 mg L−1) during 48 h (Fig. 13). We observed several changes in the polymer spectra after immersion, such as the appearance of two new bands at 786 and 920 cm−1, corresponding, respectively, to the γCr-O and γCr = O bending vibrations of Cr-O and Cr = O bonds of HCrO4 −, which indicated that Cr(VI) was adsorbed on the AHNSA-PPy surface (Ballav et al. 2012; Deng and Bai 2004). Several bands were also shifted or appeared after immersion: For example, the 3400-cm−1 band, ascribed to the νN-H stretching vibrations, was blue shifted to 3215 cm−1, and other bands (shoulders) occurred at about 3110 (νC-H stretching vibrations) and 3365 cm−1 (υO-H stretching vibrations). Finally, all these spectral changes were attributed to ionic interactions between Cr(VI) and various sites of AHNSA-PPy, which confirmed the adsorption of Cr(VI) species on AHNSA-PPy.

Chromium electro-reduction method

We developed a new method of chromium electro-reduction, based on an electrochemical process consisting to remove the heavy metal present in aqueous solution by applying between two steel electrodes a potential of −0,8 V and an electrical current of optimized constant intensity (I = 5 mA). Both electrodes were maintained parallel at a distance of 3.0 cm. The anode was a polymer-covered steel plate, and the cathode was a naked plate (submerged electrode surface area = 12 cm2).

In the chromium electro-reduction method, we electrodeposited by CV (20 cycles) the AHNSA-PPy polymer on two steel plates, respectively, used as cathode and anode, and, then, we placed these electrodes in a pH 2 potassium dichromate solution (50 mg L−1). By applying a current intensity of 5 mA, during 30, 60, 120, 240, and 360 min, a progressive discoloration of the solution occurred. As expected, we also observed a gradual and important decrease of the chromium UV-VIS absorption spectra (Fig. 14). These results indicated a disappearance of Cr(VI) due to its electro-reduction.

The analysis of the kinetics of Cr(VI) electro-reduction led to a second-order kinetic curve, since the curve 1/Ct-1/C0 as function of time was strictly linear: y = 1.39 t with a correlation coefficient r 2 = 0.999.

We obtained a rate constant value k 2 = 1.39 L mol−1 s−1. This k 2 value was about three times greater than the one measured by the immersion method, which clearly indicates that the use of the electro-reduction method significantly accelerated the chromium adsorption process on polymer, relative to the immersion method.

Application to the removal of chromium from natural waters

We used samples of the different Senegal natural waters, fortified with potassium dichromate (initial concentration = 50 mg L−1), under the above-described conditions for which all parameters (polymer mass, solution pH, electrodes, I value…) were optimized similarly to the experiments in pure water. Then, we studied the removal of chromium from these fortified natural water samples by comparing the application of the simple polymer immersion method and of the newly developed, chromium electro-reduction method.

Application of the immersion method

In the case of the immersion method, we dived the polymer-covered electrodes into the potassium dichromate-fortified natural water samples under study. Then, we followed the evolution of the chromium UV-VIS absorption spectra and ICP-OES as a function of the polymer impregnation time. For all fortified natural water samples, we observed a progressive decrease of the chromium absorption bands (especially the band at 350 nm) as a function of time, which indicated that the metal concentration decreased, in agreement with the progressive discoloration of the fortified natural water samples. As an example, we presented in Fig. 15 the evolution of the chromium UV-VIS absorption spectra with time for a fortified river water sample. The decay curve of the 350-nm absorption band, corresponding to the Cr(VI) adsorption kinetic on polymer-covered anode, obeyed a second-order kinetic relationship. Indeed, the curve of (1/Ct-1/C0) as function of time was linear: y = 0.13 t (r = 0.994). Therefore, the adsorption rate constant value was 0.13 L mol−1 s−1, about four times smaller than the value of k 2 = 0.46 L mol−1 s−1 in pure water. This important rate constant difference can be explained by the presence of other interfering metallic ions, initially present in river water, which would be more rapidly adsorbed at the polymer surface and, consequently, would inhibit and slow down the Cr(VI) adsorption kinetic on polymer.

We have given in Table 6 the values of chromium adsorption rate constant (k 2), chromium removal efficiency (R), and adsorbed chromium quantity (q t ), for all natural water samples under study. As can be seen, the k 2 values, comprised between 0.09 and 0.13 L mol−1 s−1 for the various types of natural waters, were approximately five to four times lower than the value of 0.46 L mol−1 s−1 in pure water, which again indicated the presence of other interfering metallic ions in natural waters.

The R values, measured after an impregnation time of 48 h, were high (93–95%) for all natural water samples, which demonstrated that the AHNSA-PPy polymer was able to remove the quasi-totality of chromium from fortified natural waters.

The q t values, ranging from 218 to 224 mg g−1 of polymer, were very close to the q t value of 224 mg g−1, obtained in pure water in optimized conditions, which indicated a satisfactory adsorption efficiency of the AHNSA-PPy polymer. It is worthwhile to note that our q t values were close to the q t values for Cr(VI) removal of 227 mg g−1 at 25 °C, found by Bhaumik et al. (2012) using PPy-polyaniline nanofibers as adsorbent, and of 217 mg g−1 at 25 °C, obtained by Ballav et al. (2012) with glycine-doped PPy as adsorbent. Therefore, our results showed the satisfactory adsorption capacity of AHNSA-PPy, compared to other adsorbents, and the interest of applying our simple immersion method to the adsorption of Cr(VI) in natural waters.

We can conclude from this study that the immersion method, based on AHNSA-PPy polymer, is able to remove, relatively rapidly and very efficiently, the quasi-totality of chromium ions present in fortified natural waters.

Application of the chromium electro-reduction method

In the case of the newly developed chromium electro-reduction method, we introduced the electrodes in the fortified natural waters under study, and we applied a maximum I value of 5 mA during 30, 60, 120, 240, and 360 min. We collected samples at these electrolysis times, and we followed the evolution of the chromium UV-VIS absorption spectra and ICP-OES as a function of time. In all cases, we observed a gradual decrease of the chromium absorption bands (especially the band at 350 nm) with time, which demonstrated that the metal concentration in the solution diminished, as also confirmed by the progressive discoloration of the potassium dichromate fortified water sample. The decay curve of the chromium band at 350 nm, corresponding to the Cr(VI) adsorption kinetic on polymer-covered anode, obeyed a second-order kinetic relationship. For example, in fortified river water sample, the curve of (1/Ct-1/C0) as function of time was strictly linear: y = 0.94 t (r = 0.998). The rate constant value of 0.94 L mol−1 s−1 was about seven times larger than the k 2 value of 0.13 L mol−1 s−1, obtained by the immersion method, which clearly demonstrated that the use of the electro-reduction method considerably accelerated the Cr(VI) adsorption process on polymer, as already found for pure water.

We have given in Table 7 the values of chromium adsorption rate constant, chromium removal efficiency, and adsorbed chromium quantity for all natural water samples under study. As can be seen, the rate constant values of 0.94 L mol−1 s−1 determined in river and stagnating waters, 0.70 L mol−1 s−1 in well water, and 0.35 L mol−1 s−1 in seawater were, respectively, about 1.5, 2, and 4 times smaller than k 2 = 1.39 L mol−1 s−1 in pure water. Like for the immersion method, this difference of rate constants can be attributed to the presence of other interfering metallic ions in these natural waters, which would be adsorbed more rapidly than chromium ions at the polymer surface.

The R values, determined after a Cr(VI) electro-reduction time of only 6 h, were high, in the range 94–95%. Our results demonstrated that the Cr(VI) electro-reduction method based on AHNSA-PPy was able to remove the quasi-totality of chromium from fortified natural waters within a relatively short time.

Like in the case of the immersion method, our q t values, going from 219 to 222 mg g−1 of polymer, were very close to the q t value of 224 mg g−1, obtained in pure water in optimized conditions, which again demonstrated a satisfactory adsorption efficiency of the AHNSA-PPy polymer. Also, as indicated for the immersion method, our q t values compared favorably to the literature values of 227 and 217 mg g−1 at 25 °C for Cr(VI) removal, reported, respectively, by Bhaumik et al. (2012) and Ballav et al. (2012).

Conclusion

In this work, we have been able to successfully electrosynthesize for the first time by CV in alkaline aqueous solution new, stable, and electroactive AHNSA-doped PPy polymer films, which was confirmed by our detailed, electrochemical study. Our FT-IR spectral results, obtained for the AHNSA-PPy polymer, also demonstrated that no significant change took place in the degree of substitution of the AHNSA naphthyl ring, which was not involved in the electropolymerization process, and that AHNSA doped, under its amphoteric salt form, the polymer chain. The AHNSA-PPy UV-Visible absorption spectrum revealed the presence of significant red-shifts of the strong, shortest-wavelength peaks relative to the Py corresponding bands, and of weaker bands, occurring at longer wavelength values, comparable to those of AHNSA. These spectral features again indicated the formation of AHNSA-doped PPy chains. The polymer excitation and emission fluorescence spectra, with moderate shifts relative to AHNSA, also showed that the AHNSA naphthalene derivative (entirely responsible of the fluorescence) was not involved in the electropolymerization but simply doped the polypyrrolic chains. The above-electrosynthesized AHNSA-PPy films were applied to the removal of Cr(VI) from chromium-containing aqueous solutions, using either the simple immersion method or the newly developed Cr(VI) electro-reduction method. Results of both methods showed that the efficiency of chromium removal and electro-reduction was strongly affected by the solution pH and that the maximum chromium removal efficiency was obtained for an optimum value of pH = 2. For both methods, other parameters, such as the polymer mass, type of electrodes, and applied current intensity, were also optimized to attain the Cr(VI) maximum removal efficiency. The analysis of the kinetics of chromium adsorption led to second-order kinetic curves, for both the immersion method and the Cr(VI) electro-reduction method. But, it is worthwhile to stress that the second-order rate constant values measured, using the Cr(VI) electro-reduction method, were about three times greater than those measured by the immersion method, which clearly indicated that the electro-reduction method significantly accelerated the chromium adsorption process on the AHNSA-PPy polymer. Practically, we found that it was possible to reach a 96% chromium removal within about 48 h by the simple immersion method, but only within about 6 h, by the Cr(VI) electro-reduction method. In addition, we investigated the removal of chromium from different fortified Senegal natural water samples by comparing the application of the simple polymer immersion method and of the newly developed, Cr(VI) electro-reduction method. We can conclude from these application studies that the electro-reduction method was much more rapid for maximum chromium removal than the immersion method. Moreover, very satisfactory results were obtained by both methods, with Cr(VI) removal efficiency high values comprised between 93 and 95%, according to the natural water type, and large adsorbed chromium quantity values (207–224 mg g−1 of polymer). In further studies, we are planning to examine the rapidity and efficiency of the immersion method and of the electro-reduction method, based on the use of AHNSA-PPy polymer, for the removal of other toxic metals such as cadmium and lead from aqueous media.

References

Ansari R, Fahim NK (2007) Application of polypyrrole coated on wood sawdust for removal of Cr(VI) ion from aqueous solutions. React Funct Polym 67:367–374

Armarego WLF (1971) Ultraviolet spectra of Heterocycles. Phys. Meth. 3: 67–222

Armelin E, Pla R, Liesa F, Ramis X, Iribarren JI, Alema C (2008) Corrosion protection with polyaniline and polypyrrole as anticorrosive additives for epoxy paint. Corrosion Sci 50:721–728

Ballav N, Maity A, Mishra SB (2012) High efficient removal of chromium (VI) using glycine doped polypyrrole adsorbent from aqueous solution. Chem Eng J 198–199:536–546

Banjoko V, Xu Y, Mintz E, Pang Y (2009) Synthesis of terpyridine-functionalized poly(phenylenevinylene)s: the role of meta-phenylene linkage on the Cu2+ and Zn2+. Chemosens Polym 50:2001–2009

Bhandari H, Choudhary V, Dhawan SK (2011) Influence of self-doped poly(aniline-co-4-amino-3-hydroxy-naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid) on corrosion inhibition behaviour of iron in acidic medium. Synth Met 161:753–762

Bhaumik M, Maity A, Srinivasu VV, Onyango MS (2012) Removal of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solution using polypyrrole-polyaniline nanofibers. Chem Eng J 181-182:323–333

Dahlgren G, Smith A, Wurm DB (2000) A novel self-assembled monolayer for enhanced growth of poly-N-phenylpyrrole. Synth Met 113:289–291

Deng S, Bai R (2004) Removal of trivalent and hexavalent chromium with aminated polyacrylonitrile fibre: performance and mechanism. Water Res 38:2424–2432

Denizli A, Arpa C, Bektas S, Genc O (2002) Adsorption of mercury(II) ions on Procion blue MX-3G-attached magnetic poly(vinyl alcohol) gel beads. Adsorpt Sci Technol 20:91–106

Diaw AKD, Gningue-Sall D, Fall M, Dieng MM, Aaron JJ (2008) Electrochemical synthesis and spectroscopic characterization of poly(N-phenylpyrrole) coatings in an organic medium on iron and platinum electrodes. J Chem Soc Ethiop 22:403–413

Diaw AKD, Gningue-Sall D, Yassar A, Aaron J-J (2013) New poly(p-substituted-N-phenylpyrrole)s. Electrosynthesis, electrochemical properties and characterization. Synth Met 179C:74–85

Diaw AKD, Gningue-Sall D, Yassar A, Brochon J-C, Henry E, Aaron J-J (2015) An experimental study of the electronic absorption and fluorescence spectral properties of new p-substituted-N-phenylpyrroles and their electrosynthesized polymers. Spectrochim Acta A 135:1107–1114

El-Sherif IY, Tolani S, Ofosu K, Mohamed OA, Wanekaya AK (2013) Polymeric nanofibers for the removal of Cr(III) from tannery waste water. J Environ Manag 129:410–413

Fall M, Dieng MM, Aaron J-J, Aeiyach S, Lacaze PC (2001) Role of surfactants in the electrosynthesis and the electrochemical and spectroscopic characteristics of poly(3-methoxythiophene) films in aqueous micellar media. Synth Met 118:149–155

Flamini DO, Saidman SB (2010) Electrodeposition of polypyrrole onto NiTi and the corrosion behaviour of the coated alloy. Corros Sci 52:229–234

Förstner U, Wittmann GT (1981) Metal pollution in the aquatic environment, 2nd edn. Springer-Verlag, Berlin

Fouad I, Mechbal Z, Chane-Ching K, Adenier A, Maurel F, Aaron JJ, Vodicka P, Cernovsra K, Kozmik V, Svoboda J (2004) Poly-thienobenzothiophenes, a new family of electroactive polymers: electrosynthesis and characterization. J Mater Chem 14:1711–1721

Ghorbani M, Eisazadeh H (2012) Fixed bed column study for Zn, cu, Fe and Mn removal from wastewater using nanometer size polypyrrole coated on rice husk ash. Synth Met 162:1429–1433

González MB, Saidman SB (2012) Corrosion protection properties of polypyrrole electropolymerized onto steel in the presence of salicylate. Prog Org Coat 75:178–183

Gupta RK, Singh RA, Dubey SS (2004) Removal of mercury ions from aqueous solutions by composite of polyaniline with polystyrene. Sep Purif Technol 38:225–232

Gupta VK, Suhas (2009) Application of low-cost adsorbents for dye removal – a review. J Environ Manag 90:2313–2342

Heitzmann M, Bucher C, Moutet J-C, Pereira E, Rivas BL, Royal G, Saint-Aman E (2007a) Characterization of metal cations-complexing polymer films interactions followed with anodic stripping voltammetry. J Electroanal Chem 610:147–153

Heitzmann M, Bucher C, Moutet J-C, Pereira E, Rivas BL, Royal G, Saint-Aman E (2007b) Complexation of poly(pyrrole-EDTA like) film modified electrodes: application to metal cations electroanalysis. Electrochim Acta 52:3082–3087

Johans C, Clohessy J, Fantini S, Kontturi K, Cunnane VJ (2002) Electrosynthesis of polyphenylpyrrole coated silver particles at a liquid–liquid interface. J Electrochem Comm 4:227–230

Just P-E, Chane-Ching KI, Lacroix JC, Lacaze PC (1999) Anodic oxidation of dipyrrolyls linked with conjugated spacers: study of electronic interactions between the polypyrrole chain and the spacers. J Electroanal Chem 479:3–11

Just P-E, Chang-Ching KI, Lacroix JC, Lacaze PC (2001) Electrochemical oxidation of dipyrrolyl derivatives: application to the formation of reticulated conducting polymers with conjugated spacers. Electrochim Acta 46:3279–3285

Ke CR, Chang C, Ting J (2015) Modified conducting polymer films having high catalytic activity for use as counter electrodes in rigid and flexible dye-sensitized solar cells. J Power Sources 284:489–496

Khan AA, Khan A, Habiba U, Paquiza L, Ali S (2011) Preparation and characterization of electrically conducting polypyrrole Sn(IV) phosphate cation-exchanger and its application as Mn(II) ion selective membrane electrode. J Adv Res 2:341–349

Kowalski D, Ueda M, Ohtsuka T (2007) The effect of counter anions on corrosion resistance of steel covered by bi-layered polypyrrole film. Corros Sci 49:3442–3452

Krishnani KK, Azad IS, Kailasam M, Thirunavakkarrassu AR, Gupta BP, Joseph KO, Muralidhar M, Abraham M (2003) Acute toxicity of some heavy metals to Lates calcarifer fry with a note on histopathological manifestation. J Environ Sci Health A 38:645–655

Krishnani KK, Srinives S, Mohapatra BC, Boddue VM, Haof J, Meng X, Mulchandani A (2013) Hexavalent chromium removal mechanism using conducting polymers. J Hazard Mater 252–253:99–106

Kumar PA, Chakraborty S, Ray M (2008) Removal and recovery of chromium from wastewater using short chain polyaniline synthesized on jute fiber. Chem Eng J 141:130–140

Lange U, Roznyatovskaya NV, Mirsky VM (2008) Conducting polymers in chemical sensors and arrays. Anal Chim Acta 614:1–26

Lei YH, Sheng N, Hyono A, Ueda M, Ohtsuka T (2014a) Effect of benzotriazole (BTA) addition on Polypyrrole film formation on copper and its corrosion protection. Prog Org Coat 77:339–346

Lei YH, Sheng N, Hyono A, Ueda M, Ohtsuka T (2014b) Influence of pH on the synthesis and properties of polypyrrole on copper from phytic acid solution for corrosion protection. Prog Org Coat 77:774–784

Lô C, Adenier A, Chane-Ching KI, Maurel F, Aaron JJ, Kosata B, Svoboda J (2006) A novel fluorescent conducting polymer: poly[1-thiophen-2-yl benzothieno [3,2-b] benzothiophene]. Electrosynthesis, characterization and optical properties. Synth Met 156:256–269

Lu B, Zeng L, Xu J, Le Z, Rao H (2009) Electrosynthesis of highly conducting poly(1,5 dihydroxynaphthalene)in BF3_Et2O. Eur Polym J 45:2279–2287

Mansour MS, Ossman ME, Farag HA (2011) Removal of Cd (II) ion from waste water by adsorption onto polyaniline coated on sawdust. Desalination 272:301–305

Noël V, Randriamahazaka HN (2012) Redox-assisted hydrogen bonding within interpenetrating conducting polymer networks for charge-storage materials. Electrochem Commun 19:32–35

Omraei M, Esfandian H, Katal R, Ghorbani M (2011) Study of the removal of Zn(II) from aqueous solution using polypyrrole nanocomposite. Desalination 271:248–256

Ozser ME, Yucekan I, Bodapati JB, Icil H (2013) New naphthalene polyimide with unusual molar absorption coefficient and excited state properties: synthesis, photophysics and electrochemistry. J Lumin 143:542–550

Pickup NL, Shapiro JS, Wong DKY (1998) Extraction of silver by polypyrrole films upon a base-acid treatment. Anal Chim Acta 364:41–51

Poey J, Philibert C (2000) Toxicité des métaux. Rev Fr Lab 323:35–43

Porebska GP, Stratmann M, Rohwerder M, Kamloth KP, Lu Y, Pich AZ, Adler H-J (2005) On the development of polypyrrole coatings with self-healing properties for iron corrosion protection. Corros Sci 47:3216–3233

Riaz U, Ashraf SM (2011) Semi-conducting poly(1-naphthylamine) nanotubes: a pH independent adsorbent of sulphonate dyes. Chem Eng J 174:546–555

Saranya K, Rameez M, Subramania A (2015) Developments in conducting polymer based counter electrodes for dye-sensitized solar cells – an overview. Eur Polymer J 66:207–227

Setshedi KZ, Bhaumik M, Songwane S, Onyango MS, Maity A (2013) Exfoliated polypyrrole-organically modified montmorillonite clay nanocomposite as a potential adsorbent for Cr(VI) removal. Chem Eng J 222:186–197

Sheng N, Lei Y, Hyono A, Ueda M, Ohtsuka T (2014) Improvement of polypyrrole films for corrosion protection of zinc-coated AZ91D alloy. Prog Org Coat 77:1724–1734

Shi BB, Zhang P, Wei TB, Yao H, Lin Q, Zhang YM (2013) Highly selective fluorescent sensing for CN− in water: utilization of the supramolecular self-assembly. Chem Commun 49:7812–7814

Socrates G (2004) Infrared and Raman characteristic group frequencies: tables and charts, 3rd edn. Wiley, New-York

Tian Y, Huang L, Zhou X, Wu C (2012) Electroreduction of hexavalent chromium using a polypyrrole-modified electrode under potentiostatic and potentiodynamic conditions. J Hazard Mater 225-226:15–20

Tian Y, Yang F (2007) Reduction of hexavalent chromium by polypyrrole-modified steel mesh electrode. J Clean Prod 15:1415–1418

Tsai H (2007) An investigation on the influence of electromagnetic interference induced in conducting wire of universal LEDs. Microelectron Reliab 47:959–966

Wanekaya A, Sadik OA (2002) Electrochemical detection of lead using over oxidized polypyrrole films. J Electroanal Chem 537:135–143

Wang J, Luoa C, Qi G, Pana K, Cao B (2014) Mechanism study of selective heavy metal ion removal with polypyrrole-functionalized polyacrylonitrile nanofiber mats. Appl Surf Sci 316:245–250

Xie H, Wise SS, Holmes AL, Xu B, Wakeman TP, Pelsue SE, Singh NP, Sr Wise JP (2005) Carcinogenic lead chromate induces DNA double-strand breaks in human lung cells. Mutat Res 586:160–172

Yang Y, Yuan W, Li S, Yang X, Xu J, Jiang Y (2015) Manganese dioxide nanoparticle enrichment in porous conducting polymer as high performance supercapacitor electrode materials. Electrochim Acta 165:323–329

Zanganeh AR, Amini MK (2008) Polypyrrole-modified electrodes with induced recognition sites for potentiometric and voltammetric detection of copper(II) ion. Sensors Actuators B Chem 135:358–365

Acknowledgements

One of us (M. L. Sall) gratefully thanks the French Embassy in Dakar (Senegal) for a Ph.D. grant. We also thank C. Fourdrin and D. Hugenot (LGE, Université Paris-Est Marne-la-Vallée) for recording the ICP-OES spectra.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Philippe Garrigues

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sall, M.L., Diaw, A.K.D., Gningue-Sall, D. et al. Removal of Cr(VI) from aqueous solution using electrosynthesized 4-amino-3-hydroxynaphthalene-1-sulfonic acid doped polypyrrole as adsorbent. Environ Sci Pollut Res 24, 21111–21127 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-9713-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11356-017-9713-y