Abstract

Body image victimization experiences that include appearance-based teasing, “fat talk,” and negative comments by parents and peers have been found to be associated with female adolescents’ disordered eating behaviors. Using the perspectives of the tripartite influence model and the dual-pathway model, we aimed to investigate the effect of body image victimization experiences on disordered eating behaviors among Chinese female adolescents, as well as the potential mediating role of body dissatisfaction and depression in this association. The participants were 1399 students (Mage = 13.10 years, range = 11–17) who completed assessments of body image victimization experiences, body dissatisfaction, depression, and disordered eating behaviors. The results indicated that, after controlling for age and body mass index, body image victimization experiences were positively associated with cognitive restraint eating, emotional eating, and uncontrolled eating. Body image victimization experiences influenced cognitive restraint eating through the mediating effect of body dissatisfaction and influenced emotional eating and uncontrolled eating through (a) the mediating effect of depression and (b) the serial mediating effect of body dissatisfaction and depression. These results suggest that programs aiming to prevent and reduce verbal victimization should further regard body image victimization as a key target and that intervention measures for disordered eating behaviors could help promote a better body image among young women and direct them to relieve negative affect through emotion regulation strategies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Currently, disordered eating behaviors are relatively widespread and typically emerge during adolescence (Smink et al. 2014). As reported in recent research with 2298 Australian adolescents (ages 13 to 17), from 2013 to 2014, 31.6% have engaged in disordered eating, and this behavior is more common among young women than among young men (Sparti et al. 2019). During early adolescence, alongside the onset of puberty, weight and adipose tissue (body fat) increases the conflict with a thin feminine ideal and, for some female adolescents, contributes to increases in perceived appearance pressure, body dissatisfaction, and negative affect (Thompson et al. 1999; Jackson and Chen 2014). At this developmental point, disordered eating behaviors tend to emerge and then peak in middle adolescence (Jackson and Chen 2008, 2014). Disordered eating behaviors mainly include cognitive restraint eating (i.e., individuals monitor and restrict their eating in order to lose weight), emotional eating (i.e., the tendency to eat in response to negative emotions), and uncontrolled eating (i.e., a tendency to overeat, with the feeling of being out of control; Anglé et al. 2009). These eating behaviors have been identified as maladaptive and are associated with a range of negative psychological consequences, such as a reduced ability to cope with stressful situations (Thome and Espelage 2004), a higher risk of self-harm (Ginty et al. 2012), and even higher mortality rates (Agras et al. 2004).

Because disordered eating behaviors are common and have serious negative health implications, theorists and researchers have focused on identifying the factors that influence disordered eating (Chng and Fassnacht 2016; Luo et al. 2019a; Stice et al. 2011). Sociocultural pressures regarding appearance (e.g., appearance-based teasing) have emerged as one of the most robust predictors of disordered eating across cultures (Jackson and Chen 2011, 2014; Rayner et al. 2013; Salafia and Gondoli 2011). Recently, Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia (2016a, p. 1062) developed the term “body image victimization” (BIV) to describe adolescents’ daily experiences of appearance-based teasing, “fat talk” (e.g., a critique of weight and food intake), negative comments, and verbal bullying by parents and peers. Furthermore, BIV experiences are associated with lower self-esteem and poorer body image and emotional health in adolescents (Lampard et al. 2014). However, existing studies of BIV (e.g., the pressure to be thin or teasing about a person’s weight) have mainly been conducted in Western cultures (Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia 2016a, 2016b; Lampard et al. 2014).

As teenagers integrate into their school lives and frequently interact with peers, those peers gradually become the significant others of an adolescent’s life (Brown and Larson 2009). Positive peer relationships have a positive impact on the development of adolescents (Gerner and Wilson 2005), yet verbal bullying, relational bullying, physical bullying, and victimization from peers can have a lasting negative impact on an adolescent’s well-being (Chan and Wong 2015; Yin et al. 2017), affecting their school achievements, prosocial skills, depression, anxiety, self-harm, and even suicidal behavior (Moore et al. 2017). In China, the incidence of verbal bullying is reported to be significantly higher than other forms of bullying, accounting for 23.3% of a nationally representative sample (China News Service 2017). As verbal victimization characterized by insults, name-calling, or comments about the person’s appearance (Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia 2016a), BIV is also prevalent among Chinese adolescents and serves as a significant risk factor for subsequent disordered eating (Jackson and Chen 2008, 2011, 2014). In particular, teasing and comments about appearance are more common in female than in male adolescents and these appearance-based social pressures have a greater impact on young women (e.g., resulting in more body dissatisfaction; Menzel et al. 2010; Chen and Jackson 2012). On this basis, we sought to explore the relationship between BIV experiences and disordered eating behaviors among Chinese female adolescents.

BIV Experiences and Disordered Eating Behaviors

The tripartite influence model (Thompson et al. 1999) proposes that three primary socio-cultural sources (i.e., parents, peers, and media) influence the development of body dissatisfaction and eating disturbances through two primary mechanisms: appearance comparison and internalization of the thin ideal (i.e., societal ideals of attractiveness). These influences are considered appearance pressures and contribute to subsequent disordered eating (Shroff and Thompson 2006; Thompson et al. 1999). Conceptually, BIV includes body image-related teasing, fat talk, and negative comments by parents and peers, which should also be regarded as appearance pressures and related to disordered eating. This linkage is because these pressures can motivate individuals to focus too much on their own body image and further engage in behaviors such as disordered eating to maintain or improve their physical appearance. Empirically, more sociocultural pressures regarding appearance have been found to be associated with more disordered eating behaviors among female adolescents and adult women in the United States (Olvera et al. 2013; Thompson et al. 2017), Europe (Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia 2016b), Australia (Rayner et al. 2013), and China (Jackson and Chen 2011, 2014). Based on the tripartite influence model and existing findings, we hypothesized that BIV experiences would be positively associated with disordered eating behaviors (Hypothesis 1).

Body Dissatisfaction and Depression

Body dissatisfaction is pervasive among adolescents, and it has repeatedly been found to be a proximal factor influencing disordered eating (Chng and Fassnacht 2016; Stice et al. 2011). Specifically, individuals with negative body image are more likely to engage in disordered eating behaviors (e.g., restrained eating) to reduce their unsatisfactory physical appearance, especially female adolescents who are socialized to focus on their appearance with thinness as an ideal (Vogt Yuan 2007). Evidence from the United States (Buckingham-Howes et al. 2018), China (Jackson and Chen 2008, 2011, 2014), and Australia (Slater and Tiggemann 2010) consistently reports the significant effects of body dissatisfaction on adolescents’ disordered eating behaviors.

Within the framework of the tripartite influence model (Shroff and Thompson 2006; Thompson et al. 1999), body dissatisfaction is influenced by sociocultural pressures on appearance. It has been suggested that BIV, manifesting as negative appearance evaluations and pressures, would increase the chance and frequency of a negative body image, such as body dissatisfaction (Johnson et al. 2015). Longitudinally, the pressure to be thin from parents and peers significantly predicts female adolescents’ body dissatisfaction (Salafia and Gondoli 2011). Evidence from China has also confirmed that baseline weight-related teasing contributes to the prediction of adolescents’ body dissatisfaction at an 18-month follow-up (Chen and Jackson 2009). Accordingly, we further hypothesized that body dissatisfaction would mediate the effect of BIV experiences on disordered eating behaviors, with similar patterns existing in cognitive restraint eating, emotional eating, and uncontrolled eating (Hypothesis 2a).

Depression has also been identified as a prominent risk factor for adolescents’ disordered eating behaviors (Jackson and Chen 2014; Stice et al. 2011). The dual-pathway model (Stice 2001) posits that the interaction between body dissatisfaction and negative affect predicts bulimic symptoms because eating can distract an individual from emotional distress and provide an emotional release. It suggests that when some females are immersed in a depressed mood, they tend to channel unpleasant emotions into binge eating to address this repressed situation (Wellman et al. 2019). Empirical studies have demonstrated that a greater level of depression is related to an increased likelihood of disordered eating, such as restrained eating, binge eating (Brechan and Kvalem 2015), and emotional eating (Strien et al. 2016). Furthermore, appearance pressures from parents and peers can create a toxic environment that can be detrimental to adolescents’ health. Adolescents exposed to BIV in the family or school environment may internalize beliefs regarding socially valued weight or body shape, but these beliefs are often too idealistic to be easily realized, which may further contribute to poorer emotional health, especially depression (Lampard et al. 2014). In addition, existing research has found that appearance-based teasing, comparisons, and weight stigma are positively associated with depression in female adolescents (Jackson and Chen 2007, 2008) and young adult women (Benas et al. 2010; Wellman et al. 2019). Based on the dual-pathway model and relevant evidence, we hypothesized that BIV experiences would influence the three types of disordered eating behaviors (i.e., cognitive restraint eating, emotional eating, and uncontrolled eating) through the mediating role of depression (Hypothesis 2b).

In addition, prospective studies have confirmed that baseline body dissatisfaction significantly predicts an increase in adolescents’ depression (Murray et al. 2018). Specifically, appearance pressures from parents and peers (e.g., the pressure to be thin) might be affected by mainstream appearance ideals (e.g., “thin is beautiful”), which would increase female adolescents’ body dissatisfaction and motivate them to make changes (e.g., decrease their body size) to achieve these ideals (Murray et al. 2018). However, these mainstream ideals are often too idealistic to be easily achieved, which may contribute to depression. Furthermore, the dual-pathway model (Stice 2001) posits that, for female adolescents, initial pressure to be thin and thin-ideal internalization predict subsequent growth in body dissatisfaction. Body dissatisfaction further predicts growth in dieting and negative affect, and initial dieting and negative affect predict growth in bulimic symptoms. This pattern suggests that greater appearance pressures (e.g., BIV) bring about more body dissatisfaction, and more body dissatisfaction further causes higher levels of negative affect (e.g., depression), which ultimately leads to binge-like eating (i.e., disordered eating). On this basis, we further hypothesized that BIV experiences would influence the three types of disordered eating behaviors through a serial mediating effect of body dissatisfaction and depression (Hypothesis 2c).

The Current Study

In summary, there has been a comparative lack of research into the possible relationship between daily BIV experiences and disordered eating behaviors in the Chinese context. From the perspectives of the tripartite influence model and the dual-pathway model, we sought to explore the effect of BIV experiences on disordered eating in a relatively large sample of Chinese female adolescents, as well as whether body dissatisfaction and depression mediate this relationship. The present work not only provides suggestions for parents and educators to reduce BIV but also identifies significant risk factors that influence disordered eating so that relevant practical prevention strategies and interventions can be fostered.

Method

Participants

Participants were 1399 female adolescents (grades 7 to 9) recruited from three middle schools in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. Their mean age was 13.10 years (SD = .95), ranging from 11 to 17 years-old. Their mean body mass index (BMI) was 18.65 (SD = 2.70), ranging from 12.23 to 32.87; 88.8% (n = 1242) of the participants presented low weight and normal weight, 7.1% (n = 99) were overweight (22–24 BMI), and 4.1% (n = 58) were obese. Regarding the ethnic composition of the sample, 98.4% (n = 1377) was of Han ethnicity, .6% (n = 8) was of Tujia ethnicity, and 1% (n = 14) was from other ethnic backgrounds, including the Hmong, Zhuang, Hui, and Manchu.

Measures

BIV Experiences

The Body Image Victimization Experiences Scale (BIVES; Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia 2016a) is a 12-item measure that assesses experiences of verbal bullying and teasing about physical appearance. It includes six items about BIV by parents (e.g., “My parents often comment negatively about my weight or body shape”) and six items about BIV by peers (e.g., “Classmates always tease me about my appearance”). The Chinese version of the BIVES was translated and back-translated, and then the translation was reviewed and compared to the original by a bilingual psychologist and professional translator. All items are scored on a 5-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (very frequently). We summed the ratings of all items to obtain the score for BIVES, with higher total scores indicating more frequent BIV experiences. The BIVES includes two subscales, distinguished by the response scale: frequency and emotional impact. The current study used the frequency subscale because we were more concerned about the influences of the number of BIV experiences per se on body image, depression, and disordered eating.

Because this subscale has not previously been validated in an adolescent sample, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated that this measure had good fit: χ2 (47) = 2.08 (RMSEA = .05, SRMR = .04, TLI = .96, and CFI = .97). This scale has shown adequate internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .91 [BIV by parents] and .92 [BIV by peers]) with Portuguese women (Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia 2016b). In our study, the Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .86.

Body Dissatisfaction

The Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction with Body Parts Scale (Berscheid et al. 1973) is used to measure personal dissatisfaction with nine body parts (e.g., waist, thighs). All items are rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (extremely satisfied) to 5 (extremely dissatisfied). We summed the ratings of all items to obtain the score for this scale, with higher total scores reflecting more body dissatisfaction. This scale has been used with Chinese samples and was found to have good construct validity and satisfactory internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .85 among adolescents (Jackson and Chen 2011; Mellor et al. 2013). In the current study, the Cronbach’s alpha for this scale was .94.

Depression

The Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (Radloff 1977) is a 20-item measure that assesses participants’ depression during the past week (e.g., “I felt sad”). All items are scored on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (never or rarely) to 4 (very often). To obtain the score for this scale, we reverse-scored the negatively worded items (items 4, 8, 12, 16) and then summed the ratings of all items, with higher total scores indicating a more depressed mood. This scale has been used with Chinese samples and was found to have good construct validity and high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .89 among adolescents (Cheng et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2018). The Cronbach’s alpha for this scale in the current study was .88.

Disordered Eating Behaviors

The Three-Factor Eating Questionnaire-R18 (Anglé et al. 2009) is used to evaluate participants’ disordered eating behaviors and includes six items about cognitive restraint eating (e.g., “I consciously control my eating to lose weight”), three items about emotional eating (e.g., “I comfort myself by eating when I feel lonely”), and nine items about uncontrolled eating (e.g., “Sometimes, once I have started eating, I cannot stop”). Seventeen items are scored on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree), and the last item (i.e., “To what extent do you restrict own eating”) is scored on an 8-point scale ranging from 1 (never restrict) to 8 (always restrict). We first converted the 8-point rating of the last item to a 4-point rating, and then summed the ratings of all items for each scale to obtain the subscale scores for this measure, with higher total scores reflecting more cognitive restraint eating, emotional eating, and uncontrolled eating.

Because this questionnaire has not been validated previously in an adolescent sample, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated that this measure had good fit: χ2 (118) = 3.18 (RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .05, TLI = .96, and CFI = .97). This questionnaire has been used with female Chinese participants (Kong et al. 2013) and has shown adequate internal consistency (α = .92). In the current study, the subscales had acceptable internal consistency (αs = .71 [cognitive restraint eating], .78 [emotional eating], and .88 [uncontrolled eating]).

Procedure

Before the assessment, this research was reviewed for compliance with the standards for the ethical treatment of human participants and approved by the Ethical Committee for Scientific Research at the university with which the authors are affiliated. At the beginning of the assessment, all participants and their parents/legal guardians provided written informed consent to voluntarily participate (the participants/parents were informed that their/their children’s responses would be anonymous and that participants could stop the assessment at any time). After informed consent was obtained, every participant received a pencil-and-paper survey packet including a statement about the general purpose of the study (i.e., to foster knowledge about body image and eating behaviors among adolescents from China) and one questionnaire containing the four self-report measures in the order listed in the preceding section. The questionnaires were completed in class, with participants separated by school desks. During the assessment, participants were informed to be as quiet as possible and not to converse, and they were encouraged to respond to each item carefully. After the assessment, each participant returned the survey packet to their teacher, and they were given a pencil as a reward. The questionnaires were collected from October to November 2017, and a total of 1399 questionnaires were included.

Data Analysis

SPSS (v.21; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analyses. Before the analyses, mean substitution was conducted to estimate occasional missing data points from individual measures (< 5% missing data per scale). In the preliminary analyses, descriptive statistics were performed to analyze the sample characteristics, and bivariate correlation analyses were used to examine the relationships between the study variables. Subsequently, the PROCESS macro (http://www.afhayes.com) for SPSS (Model 6), the use of which is suggested by Hayes (2013), was employed to test the hypothesized mediation model. The significance of the mediation effects was analyzed through the bootstrap resampling method, with 5000 bootstrap samples and 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) around the standardized estimates of the total, direct, and indirect effects. If the 95% percentile bootstrap CI for the indirect effect does not include zero, it is considered significant at the p < .05 level. Considering that age and BMI are important factors associated with disordered eating behaviors (Niu et al. 2019; Wilkinson et al. 2018) and that the current results showed significant correlations between age, BMI, and BIV experiences, we included age and BMI as covariates to ensure that our results were not confounded by participants’ age or BMI.

Results

Control and Test of Common Method Bias

Because all the data in our study were collected through self-report questionnaires, common method bias may exist. Thus, we performed some necessary assessments before the statistical analyses to control this bias (e.g., informing participants that all the data obtained were limited to scientific research). Moreover, a confirmatory factor analysis was conducted to determine whether a single factor could account for a significant amount of variance in these data (Podsakoff et al. 2003). The results showed a poor model fit, χ2 (1652) = 15.99, (RMSEA = .10, SRMR = .12, TLI = .31, and CFI = .34), demonstrating that the present study had no significant issue concerning common method biases for estimates of the relationships among the constructs. The test of common method bias was conducted using Mplus version 7.0 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2012).

Descriptive and Correlation Statistics

The means, standard deviations, and correlation coefficients for the study variables are presented in Table 1. In support of Hypothesis 1, which predicted that BIV experiences would be associated with disordered eating behaviors, significant positive correlations existed between BIV experiences with body dissatisfaction, depression, and disordered eating behaviors.

Mediating Model Analyses

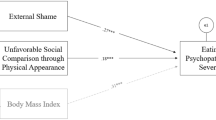

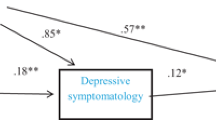

The mediating results indicated that body dissatisfaction mediated the relationship between BIV experiences and cognitive restraint eating (indirect effect = .04, SE = .01, p < .001, 95% CI = [.02, .06]; see Fig. 1a), which partially supported Hypothesis 2a which predicted that body dissatisfaction would mediate the effect of BIV experiences on disordered eating behaviors (i.e., cognitive restraint eating, emotional eating, and uncontrolled eating).

Body dissatisfaction and depression mediated the link between BIV experiences and emotional eating, which included two significant mediating pathways: (1) BIV experiences → depression → emotional eating (indirect effect = .02, SE = .01, p < .001, 95% CI = [.01, .03]) and (2) BIV experiences → body dissatisfaction → depression → emotional eating (indirect effect = .00, SE = .00, p < .001, 95% CI = [.001, .004]; see Fig. 1b). The results partially supported Hypothesis 2b which predicted that depression would mediate the effect of BIV experiences on the three types of disordered eating, as well as Hypothesis 2c which expected that that BIV experiences would influence the three types of disordered eating through a serial mediating effect of body dissatisfaction and depression.

Moreover, body dissatisfaction and depression mediated the link between BIV experiences and uncontrolled eating, which contained two significant mediating pathways: (1) BIV experiences → depression → uncontrolled eating (indirect effect = .06, SE = .01, p < .001, 95% CI = [.04, .08]) and (2) BIV experiences → body dissatisfaction → depression → uncontrolled eating (indirect effect = .01, SE = .00, p < .001, 95% CI = [.005, .013]; see Fig. 1c). The results also partially supported Hypotheses 2b and 2c. The path coefficients of the three models are presented in Fig. 1.

Discussion

Considering the prevalence of BIV experiences and disordered eating among female adolescents, the current study aimed to examine the association between daily BIV experiences and disordered eating behaviors among Chinese female adolescents, as well as the mediating effect of body dissatisfaction and depression on this association. Our results demonstrated that BIV experiences were positively associated with disordered eating behaviors, and body dissatisfaction and depression mediated this association.

Consistent with previous studies that examined the influence of appearance pressures on disordered eating among female adolescents from Western countries (Rayner et al. 2013; Thompson et al. 2017) and China (Jackson and Chen 2011, 2014), the current study found that a greater amount of BIV experiences were linked with more disordered eating behaviors. It has been suggested that BIV, as a verbal form of victimization regarding body image (Duarte and Pinto-Gouveia 2016a), involves appearance pressures that motivate female adolescents to pay more attention to their own body image and further engage in disordered eating to maintain or improve their appearance. Namely, disordered eating could act as a means of attempting to both improve physical appearance and reduce appearance pressures. In addition, the positive correlations between BIV experiences and the three types of disordered eating behaviors (i.e., cognitive restraint eating, emotional eating, and uncontrolled eating) may indicate that the sociocultural pressures regarding appearance have a relatively broad impact on female adolescents’ disordered eating and that they are not limited only to certain disordered eating behaviors.

In line with prior prospective evidence (Rayner et al. 2013), our results indicated that body dissatisfaction significantly mediated the association between BIV experiences and cognitive restraint eating among Chinese female adolescents. According to the tripartite influence model (Shroff and Thompson 2006; Thompson et al. 1999), body dissatisfaction is influenced by sociocultural pressures on appearance. BIV acts as negative appearance evaluations and pressures, thereby increasing body dissatisfaction (Chen and Jackson 2009; Salafia and Gondoli 2011). In addition, female adolescents with higher levels of body dissatisfaction are more inclined to engage in cognitive restraint eating to reduce their unsatisfactory body image (Buckingham-Howes et al. 2018; Jackson and Chen 2014). Namely, BIV experiences influence cognitive restraint eating through the mediating role of body dissatisfaction. Importantly, our results demonstrated that body dissatisfaction did not mediate the relationship between BIV experiences and emotional eating or uncontrolled eating. This finding is inconsistent with a 4-year longitudinal study that confirmed that the pressure to be thin from parents and peers increased bulimic symptoms through female adolescents’ body dissatisfaction (Salafia and Gondoli 2011). A possible interpretation of this result is that, as found in the current cross-sectional study, cognitive restraint eating may be a way to reduce female adolescents’ body dissatisfaction because female adolescents are more prone to being socialized to focus on appearance, with thinness as an ideal (Vogt Yuan 2007). However, longitudinal investigations (Salafia and Gondoli 2011; Stice 2001) have further revealed that the failure or repeated failures of cognitive restraint eating can eventually lead to bulimic symptoms.

Consistent with a previous investigation of young adult women (Wellman et al. 2019), our results further demonstrated the mediating role of depression between BIV experiences and emotional eating and uncontrolled eating among Chinese female adolescents. Specifically, individuals exposed to BIV in their family or school environment tend to internalize beliefs regarding socially valued weight or body shape, but these beliefs are often too idealistic to be easily realized, which contributes to poorer emotional health, especially depression (Lampard et al. 2014). Moreover, from the perspective of the dual-pathway model (Stice 2001), female adolescents with higher levels of depression are more prone to engage in binge-like eating (e.g., emotional eating and uncontrolled eating) because eating can bring comfort and divert attention from uncomfortable emotions. Namely, BIV experiences influence emotional eating and uncontrolled eating through the mediating role of depression. Importantly, our results showed that depression failed to mediate the relationship between BIV experiences and cognitive restraint eating. This finding suggests that, for female adolescents, overeating (i.e., emotional eating and uncontrolled eating) is likely to be a means of relieving depression.

Additionally, in line with the tenets of the dual-pathway model (Stice 2001) and relevant evidence (Murray et al. 2018), our results also indicated that BIV experiences influenced female adolescents’ emotional eating and uncontrolled eating through the serial mediating effect of body dissatisfaction and depression. Specifically, appearance pressures from parents and peers (e.g., the pressure to be thin) are affected by mainstream appearance ideals (e.g., “thin is beautiful”), which may increase female adolescents’ body dissatisfaction (Salafia and Gondoli 2011) and motivate them to make changes (e.g., to decrease their body size) in order to achieve these ideals and reduce BIV. However, mainstream ideals are often too unrealistic to be easily achieved, which may increase the risk of depression (Lampard et al. 2014). To eliminate this depressive situation, female adolescents eventually tend to engage in disordered eating behaviors, especially overeating (Jackson and Chen 2014; Stice 2001). In addition, our results demonstrated that body dissatisfaction and depression were not serial mediators of the association between BIV experiences and cognitive restraint eating, which again suggests that overeating may act as an effective way to relieve depression for female adolescents.

By and large, the present research contributes to the previous literature by revealing that body dissatisfaction and depression are significant risk factors that explain the relationship between daily BIV experiences and disordered eating in Chinese female adolescents. In addition, our findings expand the tripartite influence model by identifying that body dissatisfaction serves as a mediator between BIV experiences and cognitive restraint eating more than just the consequences of appearance pressures. Moreover, our findings provide empirical support for the dual-pathway model and suggest that the interaction between body dissatisfaction and depression is of great value for explaining the links between BIV experiences and emotional eating and uncontrolled eating. Last but not least, given that physical appearance plays a key role in social network site activities (Vries et al. 2016), increasing evidence indicates the importance of social media as a context for appearance-based feedback and comments (e.g., Chua and Chang 2016; Vries et al. 2016; Luo et al. 2019b). Furthermore, social media experiences (e.g., reading friend posts, likes/comments) have been found to be associated with female adolescents’ body dissatisfaction, depression, and disordered eating (Burnette et al. 2017; Latzer et al. 2015; Li et al. 2018), which can contribute to investigating BIV specifically in the context of social media in future research.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

When considering our findings, it is important to note the limitations of our study. First, its limitations included the cross-sectional design that precludes the inference of causality. Future longitudinal and experimental studies that can provide information about the direction and temporal relationships among the study variables are still necessary. Second, although BIV experiences, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating behaviors are more common among female adolescents (Rogers et al. 2017; Salafia and Gondoli 2011), they are also exhibited in male adolescents (Wellman et al. 2019). Future studies should include male adolescents and further investigate possible gender differences. Third, the limited generalizability of our findings should be acknowledged, and a diverse range of participants (e.g., different genders, levels of education, and cultural backgrounds) are required in future research. Fourth, considering that appearance-based verbal bullying and victimization mainly occur in schools (Yin et al. 2017), there may be different associations between disordered eating behaviors and appearance pressures from peers versus parents, which should be examined in future studies. In addition, our research can be extended by considering other mediators or moderators (e.g., body appreciation, self-compassion) of the association between BIV experiences and disordered eating behaviors as well as the prevention and intervention of BIV based on psychological factors.

Practice Implications

The present study has important implications for practitioners. Our findings indicate that daily BIV experiences increase the likelihood of female adolescents’ body dissatisfaction, depression, and subsequent disordered eating behaviors. As an effective parent-targeted prevention program, the Healthy Girls Project (Corning et al. 2010) aims to guide mothers to understand and recognize the pervasiveness and insidiousness of the thin-ideal so they might work to mitigate its effects on their daughters (e.g., pressure to be thin, body dissatisfaction) via their relationships with their daughters. However, the current school-based bullying programs in the United States (Farrell et al. 2018), Norway (Limber 2011), China (Chan and Wong 2015), and South Korea (Hong et al. 2013) have rarely focused on appearance-related victimization. Specifically, the Olweus Bully Prevention Program (Farrell et al. 2018; Limber 2011) is designed to promote a positive and responsive school climate characterized by low rates of victimization (verbal, relational, and physical) and high rates of prosocial relations through specific program components at school level (e.g., identify “hot spots” where bullying behaviors are more likely to occur), classroom level (e.g., discuss bullying-related topics), and individual level (e.g., “on-the-spot” interventions). On this basis, future programs aiming to prevent and reduce verbal victimization should further regard BIV as a key target, specifically in the context of families and schools, and could integrate appearance-related factors into specific intervention activities, such as discussing the negative impacts of BIV on an individual’s body image and eating patterns.

In addition, body dissatisfaction and depression are the most proximal factors that should be addressed to reduce disordered eating, and possibly even serious outcomes, such as anorexia nervosa (Tong et al. 2013) and obesity (Olson et al. 2018). The Body Project (Rohde et al. 2014; Stice and Presnell 2007) has effectively helped female adolescents promote a better body image and reduce negative affect and unhealthy eating behaviors through a series of activities (e.g., resist the thin-ideal). However, reducing depression has rarely been shown to reduce adolescents’ disordered eating in prior programs. The present findings suggest that intervention measures for disordered eating behaviors could be designed to relieve depression through emotion regulation strategies, such as mindfulness and cognitive reappraisal (Brockman et al. 2017; Goldschmidt et al. 2017).

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that BIV experiences, body dissatisfaction, and depression are significant risk factors for Chinese female adolescents’ disordered eating behaviors, and they further reveal that body dissatisfaction and depression are of great value for explaining the relationship between BIV experiences and disordered eating behaviors. These findings highlight the importance of research that targets daily BIV experiences in relation to disordered eating in the Chinese context, as well as the need for further interventions for negative body image and negative affect.

References

Agras, W. S., Brandt, H. A., Bulik, C. M., Dolan-Sewell, R., Fairburn, C. G., Halmi, K. A., … Wilfley, D. E. (2004). Report of the national institutes of health workshop on overcoming barriers to treatment research in anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35, 509–521. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10261.

Anglé, S., Engblom, J., Eriksson, T., Kautiainen, S., Saha, M. T., Lindfors, P., … Rimpelä, A. (2009). Three factor eating questionnaire-R18 as a measure of cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating in a sample of young Finnish females. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 6, 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-6-41.

Benas, J. S., Uhrlass, D. J., & Gibb, B. E. (2010). Body dissatisfaction and weight-related teasing: A model of cognitive vulnerability to depression among women. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 41, 352–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2010.03.006.

Berscheid, E., Walster, E., & Bohrnstedt, G. (1973). The happy American body: A survey report. Psychology Today, 7, 119–131. Retrieved from https://www.mendeley.com/catalogue/happy-american-body-survey-report/.

Brechan, I., & Kvalem, I. L. (2015). Relationship between body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: Mediating role of self-esteem and depression. Eating Behaviors, 17, 49–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.12.008.

Brockman, R., Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P., & Kashdan, T. (2017). Emotion regulation strategies in daily life: Mindfulness, cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46, 91–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2016.1218926.

Brown, B. B., & Larson, J. (2009). Peer relationships in adolescence. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (pp. 74–103). Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470479193.adlpsy002004.

Buckingham-Howes, S., Armstrong, B., & Pejsareitz, M. C. (2018). BMI and disordered eating in urban, African American, adolescent girls: The mediating role of body dissatisfaction. Eating Behaviors, 29, 59–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.02.006.

Burnette, C. B., Kwitowski, M. A., & Mazzeo, S. E. (2017). “I don’t need people to tell me I’m pretty on social media:” a qualitative study of social media and body image in early adolescent girls. Body Image, 23, 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.09.001.

Chan, H. C., & Wong, D. S. W. (2015). Traditional school bullying and cyberbullying in Chinese societies: Prevalence and a review of the whole-school intervention approach. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 23, 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2015.05.010.

Chen, H., & Jackson, T. (2009). Predictors of changes in weight esteem among mainland Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal analysis. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1618–1629. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016820.

Chen, H., & Jackson, T. (2012). Gender and age group differences in mass media and interpersonal influences on body dissatisfaction among Chinese adolescents. Sex Roles, 66, 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0056-8.

Cheng, C. P., Yen, C. F., Ko, C. H., & Yen, J. Y. (2012). Factor structure of the center for epidemiologic studies depression scale in Taiwanese adolescents. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 53, 299–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2011.04.056.

China News Service. (2017). The investigation report on school bullying in China: Verbal bullying is the main form bullying. Retrieved on May 21, 2017 from http://www.chinanews.com/sh/2017/05-21/8229705.shtml.

Chng, S. C. W., & Fassnacht, D. B. (2016). Parental comments: Relationship with gender, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating in Asian young adults. Body Image, 16, 93–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.12.001.

Chua, T. H. H., & Chang, L. (2016). Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.011.

Corning, A. F., Gondoli, D. M., Bucchianeri, M. M., & Salafia, E. H. B. (2010). Preventing the development of body issues in adolescent girls through intervention with their mothers. Body Image, 7, 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.08.001.

Duarte, C., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2016a). Body image as a target of victimization by peers/parents: Development and validation of the body image victimization experiences scale. Women and Health, 57, 1061–1079. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2016.1243603.

Duarte, C., & Pinto-Gouveia, J. (2016b). Body image flexibility mediates the effect of body image-related victimization experiences and shame on binge eating and weight. Eating Behaviors, 23, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.07.005.

Farrell, A. D., Sullivan, T. N., Sutherland, K. S., Corona, R., & Masho, S. (2018). Evaluation of the olweus bully prevention program in an urban school system in the USA. Prevention Science, 19, 833–847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0923-4.

Gerner, B., & Wilson, P. H. (2005). The relationship between friendship factors and adolescent girls’ body image concern, body dissatisfaction, and restrained eating. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 37, 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20094.

Ginty, A. T., Phillips, A. C., Higgs, S., Heaney, J. L., & Carroll, D. (2012). Disordered eating behaviour is associated with blunted cortisol and cardiovascular reactions to acute psychological stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37, 715–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.09.004.

Goldschmidt, A. B., Lavender, J. M., Hipwell, A. E., Stepp, S. D., & Keenan, K. (2017). Emotion regulation and loss of control eating in community-based adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45, 183–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0152-x.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis: A regression based approach. New York: Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12050.

Hong, J. S., Lee, C. H., Lee, J., Lee, N. Y., & Garbarino, J. (2013). A review of bullying prevention and intervention in south Korean schools: An application of the social-ecological framework. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 45, 433–442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-013-0413-7.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2007). Identifying the eating disorder symptomatic in China: The role of sociocultural factors and culturally defined appearance concerns. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 62, 241–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.09.010.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2008). Predicting changes in eating disorder symptoms among adolescents in China: An 18-month prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 874–885. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374410802359841.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2011). Risk factors for disordered eating during early and middle adolescence: Prospective evidence from mainland Chinese boys and girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 120, 454–464. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022122.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2014). Risk factors for disordered eating during early and middle adolescence: A two year longitudinal study of mainland Chinese boys and girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 42, 791–802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9823-z.

Johnson, S. M., Edwards, K. M., & Gidycz, C. A. (2015). Interpersonal weight-related pressure and disordered eating in college women: A test of an expanded tripartite influence model. Sex Roles, 72, 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0442-0.

Kong, F., Zhang, Y., & Chen, H. (2013). The construct validity of the restraint scale among mainland Chinese women. Eating Behaviors, 14, 356–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.06.009.

Lampard, A. M., Maclehose, R. F., Eisenberg, M. E., Neumark-Sztainer, D., & Davison, K. K. (2014). Weight-related teasing in the school environment: Associations with psychosocial health and weight control practices among adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43, 1770–1780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-0086-3.

Latzer, Y., Spivak-Lavi, Z., & Katz, R. (2015). Disordered eating and media exposure among adolescent girls: The role of parental involvement and sense of empowerment. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 20, 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2015.1014925.

Li, P., Chang, L., Chua, T. H. H., & Loh, R. S. M. (2018). “Likes” as KPI: An examination of teenage girls’ perspective on peer feedback on Instagram and its influence on coping response. Telematics and Informatics, 35, 1994–2005. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.07.003.

Limber, S. P. (2011). Development, evaluation, and future directions of the Olweus bullying prevention program. Journal of School Violence, 10, 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2010.519375.

Luo, Y., Jackson, T., Niu, G., & Chen, H. (2019a). Effects of gender and appearance comparisons on associations between media-based appearance pressure and disordered eating: Testing a moderated mediation model. Sex Roles. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01058-4, 1, 13.

Luo, Y., Niu, G., Kong, F., & Chen, H. (2019b). Online interpersonal sexual objectification experiences and Chinese adolescent girls’ intuitive eating: The role of broad conceptualization of beauty and body appreciation. Eating Behaviors, 33, 55–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2019.03.004.

Mellor, D., Waterhouse, M., Mamat, N. H. B., Xu, X., Cochrane, J., Mccabe, M., & Ricciardelli, L. (2013). Which body features are associated with female adolescents’ body dissatisfaction? A cross-cultural study in Australia, China and Malaysia. Body Image, 10, 54–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.10.002.

Menzel, J. E., Schaefer, L. M., Burke, N. L., Mayhew, L. L., Brannick, M. T., & Thompson, J. K. (2010). Appearance-related teasing, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. Body Image, 7, 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.05.004.

Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7, 60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60.

Murray, K., Rieger, E., & Byrne, D. (2018). Body image predictors of depressive symptoms in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 69, 130–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.10.002.

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén. Retrieved from http://refhub.elsevier.com/S1471-0153(17)30224-6/rf0155.

Niu, G., Sun, L., Liu, Q., Chai, H., Sun, X., & Zhou, Z. (2019). Selfie-posting and young adult women’s restrained eating: The role of commentary on appearance and self-objectification. Sex Roles. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01045-9.

Olson, K. L., Thaxton, T. T., & Emery, C. F. (2018). Targeting body dissatisfaction among women with overweight or obesity: A proof-of-concept pilot study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 51, 973–977. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22874.

Olvera, N., Dempsey, A., Gonzalez, E., & Abrahamson, C. (2013). Weight-related teasing, emotional eating, and weight control behaviors in Hispanic and African American girls. Eating Behaviors, 14, 513–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.06.012.

Podsakoff, P. M., Mackenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 3, 385–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167700100306.

Rayner, K. E., Schniering, C. A., Rapee, R. M., & Hutchinson, D. M. (2013). A longitudinal investigation of perceived friend influence on adolescent girls’ body dissatisfaction and disordered eating. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 42, 643–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.743103.

Rogers, C. B., Martz, D. M., Webb, R. M., & Galloway, A. T. (2017). Everyone else is doing it (I think): The power of perception in fat talk. Body Image, 20, 116–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.01.004.

Rohde, P., Auslander, B. A., Shaw, H., Raineri, K. M., Gau, J. M., & Stice, E. (2014). Dissonance-based prevention of eating disorder risk factors in middle school girls: Results from two pilot trials. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47, 483–494. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22253.

Salafia, E. H. B., & Gondoli, D. M. (2011). A 4-year longitudinal investigation of the processes by which parents and peers influence the development of early adolescent girls’ bulimic symptoms. Journal of Early Adolescence, 31, 390–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431610366248.

Shroff, H., & Thompson, J. K. (2006). Peer influences, body-image dissatisfaction, eating dysfunction and self-esteem in adolescent girls. Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 533–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105306065015.

Slater, A., & Tiggemann, M. (2010). Body image and disordered eating in adolescent girls and boys: A test of objectification theory. Sex Roles, 63, 42–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9794-2.

Smink, F. R., Van Hoeken, D., Oldehinkel, A. J., & Hoek, H. W. (2014). Prevalence and severity of DSM-5 eating disorders in a community cohort of adolescents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 47, 610–619. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22316.

Sparti, C., Santomauro, D., Cruwys, T., Burgess, P., & Harris, M. (2019). Disordered eating among Australian adolescents: Prevalence, functioning, and help received. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52, 246–254. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23032.

Stice, E. (2001). A prospective test of the dual-pathway model of bulimic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843x.110.1.124.

Stice, E., Marti, C. N., & Durant, S. (2011). Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: Evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49, 622–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.009.

Stice, E., & Presnell, K. (2007). The body project: Promoting body acceptance and preventing eating disorders: Facilitator guide. New York: Oxford University Press https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2007-10085-000.

Strien, T. V., Konttinen, H., Homberg, J. R., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Winkens, L. H. H. (2016). Emotional eating as a mediator between depression and weight gain. Appetite, 100, 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2016.02.034.

Thome, J., & Espelage, D. L. (2004). Relations among exercise, coping, disordered eating, and psychological health among college students. Eating Behaviors, 5, 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2004.04.002.

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10312-000.

Thompson, K. A., Kelly, N. R., Schvey, N. A., Brady, S. M., Courville, A. B., Tanofsky-Kraff, M., … Shomaker, L. B. (2017). Internalization of appearance ideals mediates the relationship between appearance-related pressures from peers and emotional eating among adolescent boys and girls. Eating Behaviors, 24, 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.12.008.

Tong, J., Miao, S., Wang, J., Yang, F., Lai, H., Zhang, C., … Hsu, L. K. (2013). A two-stage epidemiologic study on prevalence of eating disorders in female university students in Wuhan, China. Social Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49, 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0694-y.

Vogt Yuan, A. S. (2007). Gender differences in the relationship of puberty with adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Do body perceptions matter? Sex Roles, 57, 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9212-6.

Vries, D. A., Peter, J., de Graaf, H., & Nikken, P. (2016). Adolescents’ social network site use, peer appearance-related feedback, and body dissatisfaction: Testing a mediation model. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45, 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-015-0266-4.

Wellman, J. D., Araiza, A. M., Solano, C., & Berru, E. (2019). Sex differences in the relationships among weight stigma, depression, and binge eating. Appetite, 133, 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.10.029.

Wilkinson, L. L., Rowe, A. C., Robinson, E., & Hardman, C. A. (2018). Explaining the relationship between attachment anxiety, eating behaviour and BMI. Appetite, 127, 214–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2018.04.029.

Yang, X., Lau, J. T. F., & Lau, M. C. M. (2018). Predictors of remission from probable depression among Hong Kong adolescents – A large-scale longitudinal study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 229, 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.12.080.

Yin, X. Q., Wang, L. H., Zhang, G. D., Liang, X. B., Li, J., Zimmerman, M. A., & Wang, J. L. (2017). The promotive effects of peer support and active coping on the relationship between bullying victimization and depression among Chinese boarding students. Psychiatry Research, 256, 59–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.06.037.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jinyinhu, Changqing, and Jiangjun Road Middle School for their support of this research. We would also like to thank the Editage (www.editage.cn) for English language editing.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31771237) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (No. SWU1709106, No. SWU1809355).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and national research committee.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human Participants

All ethical guidelines for human subjects’ research were followed.

Informed Consent

All participants and their parents/legal guardians provided written informed consents to participate in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, X., Luo, Yj. & Chen, H. Body Image Victimization Experiences and Disordered Eating Behaviors among Chinese Female Adolescents: The Role of Body Dissatisfaction and Depression. Sex Roles 83, 442–452 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01122-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01122-4