Abstract

Research has demonstrated that interpersonal weight-related pressures and criticisms are related to body dissatisfaction among college women. Further, research has suggested that romantic partners, in comparison to family and peers, play an increasingly important role in college women’s body dissatisfaction. However, research has been inconsistent on the roles that these sources of interpersonal weight-related pressure and criticism play in college women’s body dissatisfaction. The influence of romantic partners on college women’s body dissatisfaction is important to examine given that college women are developmentally at a time in their lives where issues related to romantic relationships become more salient. Even more, understanding of the influences on college women’s body dissatisfaction and resultant disordered eating is critical so that effective prevention and intervention efforts can be developed. Thus, this study examined the influence of family, peer, romantic partner, media weight-related pressures and criticisms on body dissatisfaction and resultant disordered eating (i.e., dieting and bulimic behaviors) among college women. Participants included undergraduate college women (N = 246) recruited from introductory psychology courses from a mid-sized U.S. Midwestern university. Women completed paper and pencil surveys for course credit. Path analytic results demonstrated that partner and media pressures were related to internalization of the thin ideal, and that family, peer, and media pressures along with internalization of the thin ideal were related to body dissatisfaction. Moreover, body dissatisfaction was related to maladaptive dieting and bulimic behaviors. Prevention and intervention efforts aimed at reducing the impact of various forms of weight-related pressure, especially the media, appear crucial.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Body dissatisfaction is especially problematic for U.S. young women (Forbes et al. 2012). Given this, the focus of the current study is young women in the United States, although some research conducted in other Western and non-Western countries will be referenced in this article. Recent research has suggested that sociocultural influences (e.g., media, family pressures) are important to the formation of women’s body image as transmitters of cultural ideals for appearance as well as weight/shape in the United States (Grabe et al. 2008). In addition, recent research has suggested that salience of these sociocultural influences (e.g., family versus peer influences) to body image and disordered eating (e.g., Eisenberg et al. 2013) as well the pathways (e.g., internalization of the thin ideal) through which they impact body image (Rodgers et al. 2011) may vary over the lifespan as U.S. women develop through adolescence and adulthood. However, limited research currently exists on how romantic partners influence U.S. college women’s body dissatisfaction in relation to other sociocultural sources, despite recent research suggesting that romantic partners are an important influence on U.S. women’s disordered eating behaviors (Eisenberg et al. 2013) and the fact that young women are developmentally at a time in their lives where issues related to romantic relationships become more salient (Arnett 2000). Clarification of these relationships are critical given that a recent meta-analysis showed that the bulk of prevention programming in the United States is either not effective or only modestly effective in preventing body dissatisfaction and disordered eating (for a review, see Stice et al. 2008). Clearly, greater refinement of variables that should be targeted is needed in order to design the most effective intervention and prevention programming. In order to explore the gap in the literature, the purpose of the current study was to 1) assess how weight-related pressures and criticisms from family, peers, and romantic partners, as well as pressure from the media, relate to heterosexual U.S. college women’s body dissatisfaction and resultant disordered eating, and 2) examine the pathways through which pressures and criticisms from family, peers, and romantic partners, as well as the media, impact body dissatisfaction and resultant disordered eating.

Body dissatisfaction has been defined as “negative subjective evaluations of one’s physical body” (Stice and Shaw 2002, p. 985). Even more, U.S. standards for appearance and body weight/shape have grown increasingly narrow and dissatisfaction with one’s body has become “normative” among women in the U.S. (Silberstein et al. 1988). Many factors have been shown to contribute to the development of body dissatisfaction among U.S. young women. For example, Tiggemann (2005) showed that lower self-esteem was related to increased body dissatisfaction among U.S. adolescent girls. In addition, gender is one important variable to consider in the development of body dissatisfaction for U.S. women (for a review, see Cash et al. 1997). Fredrickson and Roberts (1997) suggest that U.S. women are subject to a greater number of messages regarding appearance, weight, and shape in comparison to men and numerous studies have documented the stark contrasts in these depictions of men and women (e.g., Miller and Summers 2007, U.S.). In addition, others have suggested that U.S. women are encouraged to pay greater attention to their shape/weight and appearance (for a review, see Cash et al. 1997). Of note, U.S. feminist scholars have suggested that appearance and weight/shape are one way through which women gain power in our society where other avenues to power are often not available to them (e.g., Wolf 1991).

Investment in appearance and weight/shape is especially important when considering heterosexual dating relationships in the United States (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Briefly, objectification theory proposes that women’s bodies are sexualized by men, which leads to women being treated and treating themselves as objects whose value depends on their appearance. Research with U.S. adult heterosexual couples has shown men’s actual desired changes in women’s bodies (e.g., smaller body shape) are related to increases in women’s eating, weight, and shape concerns (Morrison et al. 2009). For example, women’s drive for thinness was predicted by their perceptions that their male partner wished them to be thinner. It should be noted that, although U.S. men are facing increasing pressure to achieve more narrow expectations for appearance and weight/shape (Jones and Morgan 2010), research with college students in the U.S. continues to show that women report greater body dissatisfaction than men (Grossbard et al. 2011).

Many researchers have suggested that media is the main venue through which messages regarding appearance, weight, and shape are communicated to young women (e.g., Thompson et al. 1999) and media pressures regarding weight and shape have shown associations with U.S. women’s body dissatisfaction in multiple studies (Grabe et al. 2008). Research has demonstrated that awareness and consumption of media containing the thin ideal (standard of female beauty presented in media such as television and magazines which involves thinness as a main component; McCarthy 1990) is related to increased body dissatisfaction among U.S. women (for a review, see Groesz et al. 2002). However, researchers have theorized that living in a culture where the ideal of beauty is unattainable for most is not solely responsible for the production of body dissatisfaction (e.g., Thompson et al. 1999). In fact, research has shown that internalization of these ideals may be more salient to increased body dissatisfaction than mere awareness or consumption of media containing these ideals (for a review, see Thompson and Stice 2001). Internalization can be defined as the incorporation of beliefs concerning weight and shape (Tester and Gleaves 2005).

In addition to receiving these messages through media, U.S. researchers have theorized that these messages are also transmitted by family members through modeling and appearance-related feedback (weight-related pressures and criticism; Fredrickson and Roberts 1997; Thompson et al. 1999). These messages may be transmitted covertly (e.g., a mother may send messages to her daughter regarding weight and shape by her own engagement in dieting) or overtly (a sibling calling their sibling “fat.”). Shapiro et al. (1991; for a review, see Thompson et al. 1999) theorize that peer teasing serves to promote conformity to group norms. In this way, weight-related pressure and criticism would serve to promote adherence to societal norms of weight and shape. A recent meta-analysis examined the impact of weight-related pressures from family members and body dissatisfaction (Menzel et al. 2010). Results showed bivariate relationships between these pressures and body dissatisfaction and failed to show a moderating impact of culture. It is important to note that culture was defined as “Western” or “Eastern” by Menzel and colleagues (2010). Thus, it appears that family members are an important influence on women’s body dissatisfaction. However, as U.S. girls enter adolescence, they increasingly turn to peers and romantic partners as sources of information and support (Arnett 2000; Tanner 2012). Over time, both peers and romantic partners replace family as a source of support and feedback. Research with samples of U.S. college women have also shown bivariate relationships between weight-related pressures from peers (Krones et al. 2005) and romantic partners (Befort et al. 2001) and body dissatisfaction.

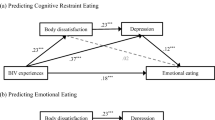

In order to explicate these pathways between sociocultural messages regarding weight and shape (including familial, peer, and media influences) that impact U.S. women’s body dissatisfaction and resultant disordered eating, Thompson and colleagues (1999) proposed the tripartite influence model. In this model, Thompson and colleagues assert that parents, peers, and media contribute to body image concerns and disordered eating. In addition, Thompson and colleagues propose that these sociocultural influences impact women’s body image and disordered eating through internalization of the thin ideal. Research has shown that women with higher internalization levels experience greater body dissatisfaction in response to weight-related pressure or criticism with samples from Australia, France, and Japan (Rodgers et al. 2011; Yamamiya et al. 2008) which then lead to increased disordered eating and related symptoms (e.g., drive for thinness, bulimic behaviors). Limited research with samples of college women from Australia, France, Japan, and the United States, examined multiple weight-related pressures and criticisms simultaneously in association with body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among college women (Rodgers et al. 2011; Yamamiya et al. 2008; Van den Berg et al. 2002). Overall, results were generally supportive of the tripartite influence model.

Although the tripartite influence model does not include romantic partners, one study with U.S. adolescents (Schomaker and Furman 2009) found that weight-related pressures and criticisms from romantic partners prospectively predicted increases in disordered eating over 12 months. Thompson and colleagues (1999) also note that women spend a great deal of time with their romantic partners and this may influence their body satisfaction. In addition, in a recent study Eisenberg and colleagues (2013) examined the impact of dieting and encouragement of dieting by romantic partners on disordered eating among U.S. middle- and high-school students. Results showed that encouragement of dieting was common in this age group and that romantic partner dieting and encouragement to diet was found to be related to disordered eating, especially among girl students. Even more, when perceived romantic partner dieting and encouragement to diet were included simultaneously as predictors, encouragement to diet remained significantly related to disordered eating. These authors conclude that romantic partners are an important source of social influence of disordered eating and should be a main focus of prevention and intervention efforts. However, no research has examined the tripartite model with the inclusion of romantic partners in U.S. college women. Given that it is likely that the influence of romantic partners grows throughout the college years, it is critical to understand the role that they play in college women’s body image and resultant disordered eating in order to design effective prevention and intervention efforts. Additionally, it is currently unclear whether weight-related pressure and criticism from romantic partners also affects heterosexual college women’s body dissatisfaction and disordered eating through the same mechanisms that media, peer, and family influences have been shown to affect women’s body dissatisfaction and disordered eating. Specifically, the impact of media, peer, and familial influences on women’s body dissatisfaction have been shown to be mediated by internalization of the thin ideal (Rodgers et al. 2011; Yamamiya et al. 2008). This body dissatisfaction was then related to women’s engagement in disordered eating. Research is needed to determine if the impact of romantic partner influences on body dissatisfaction are particularly salient for women with high pre-existing levels of internalization of the thin ideal.

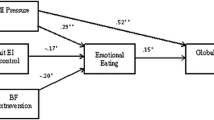

In sum, there is a growing body of research supporting the tripartite influence model of body image and disordered eating among U.S. college women. However, research with college women utilizing the tripartite influence model has not yet examined the model with the inclusion of romantic partner weight-related criticisms and pressures. In order to best design intervention and prevention efforts, it is critical to fully understand all variables that may affect women’s body dissatisfaction and disordered eating as body dissatisfaction and disordered eating are problematic among U.S. college women (e.g., Forbes et al. 2012). Given that college is a time of increasing independence from families and growing involvement with romantic partners, it is important to understand the relative importance of different sources of influence on women’s body dissatisfaction during this developmental stage. Thus, we tested a model that included all possible sources of weight-related pressures and criticisms, internalization of the thin ideal, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating (see Fig. 1 for hypothesized model). We generally hypothesized that weight-related pressures and criticisms from friends, family, and partners as well as media pressures would be positively related to internalization of the thin ideal, which would be positively related to body dissatisfaction. Further, body dissatisfaction was hypothesized to be positively related to disordered eating behaviors.

Method

Participants

Participants were 246 undergraduate women at a medium-size, Midwestern University. In order to obtain information about weight-related pressures and criticisms from romantic partners, all participants were currently in heterosexual dating relationships of varying lengths (M = 14.78 months, SD = 13.54 months, Range = .50–72.00 months). The sample was largely young (M = 18.74, SD = .93, Range = 18.00–22.00) and mostly first year students (68 %). The average Body Mass Index (BMI) was 23.01 which falls within the normal range (SD = 3.69, Range = 17.71–42.51). Eighty-nine percent of the sample was Caucasian, 6 % was African American, 2 % was Latino or Hispanic, 1 % was Asian or Pacific Islander, 1 % was two or more races, and <1 % was Other. Approximately 25 % of the sample reported family incomes under $50,000, 40 % between $50,000 and $100,000, and 33 % over $100,000.

Procedure

Women were recruited from introductory psychology classes via the Department of Psychology Experiment Sign-Up System. Recruitment information informed women that to participate they must be “currently involved in a dating relationship” and 18 years of age or older. The current study was advertised as “Women’s Social and Relationship Experiences.” Participants completed the study in a group format environment that included informed consent, anonymous completion of the paper and pencil survey, and debriefing and referral information. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University where the data were collected.

Measures

Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26)

Disordered eating patterns were assessed using the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT-26; Garner et al. 1982). The measure contains 26 items and has a total score and three subscales: Dieting (“Am terrified about being overweight”), Bulimia and Food Preoccupation (“Have gone on eating binges where I feel that I may not be able to stop”), and Oral Control (“Cut my food into small pieces”). Items are responded to on a 6-point scale (3 zero values) ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always). Higher scores are indicative of greater disordered eating. In the current sample, the internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α) were .88 (Dieting), .74 (Bulimia and Food Preoccupation), and .39 (Oral Control). Given the poor internal consistency of the oral control subscale, this scale was not used in the current analyses. We chose to keep the Dieting and Bulimia and Food Preoccupation subscales as separate outcome variables given that research has found that women with different eating disorders (anorexia nervosa versus bulimia nervosa) score significantly different on these subscales, but not the total score (Garner et al. 1982). Mean scores were computed for these subscales. The EAT-26 has shown good construct validity, with a 90 % accuracy rate distinguishing patients with eating disorders from those without (Mintz and O’Halloran 2000).

Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ)

Body and weight dissatisfaction (weight and shape concerns) was assessed by the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ; Cooper et al. 1987). The BSQ contains 34 items and a sample item is, “Have you felt excessively large and rounded?” Items are answered on a 6-point scale ranging from where 1 (never) to 6 (always). A mean score was computed for body dissatisfaction. Higher scores are indicative of greater body dissatisfaction. The BSQ has demonstrated convergent validity with both clinical and nonclinical populations (Cooper et al. 1987). The internal consistency of the BSQ was .97

Internalization Scale

The Internalization subscale from the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire (SATAQ-III; Heinberg et al. 1995; Thompson et al. 2004) was administered to assess internalization of the thin ideal. The subscale has seven items and a sample item from the subscale is, “I would like my body to look like the models who appear in magazines.” Response options are on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree). Consistent with the other subscales, a mean score was computed. Higher scores are indicative of greater internalization of the thin ideal. In the current sample, the internal consistency of the Internalization subscale was .93.

Media Pressure Scale

The Pressures subscale from the SATAQ-III was also administered to assess pressures from the media. The subscale has seven items and a sample item from the subscale is, “I’ve felt pressure from TV or magazines to change my appearance.” Response options are on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree). Consistent with the other subscales, a mean score was computed. In the current sample, the internal consistency of the media Pressures subscale was .93. Higher scores are indicative of greater pressure from the media.

Peer, Parents, and Partner Weight-related Pressures and Criticism Scale

Weight-related criticisms from partners, peers, and family were assessed using St. Peter’s (1997) four-item scale that was later adapted by Befort et al. (2001) and weight-related pressures from peers, parents, and partners were assessed using a modified version of Pressures scale from the SATAQ-III. The weight-related Criticisms scale was modified to measure criticism from peers and family by substituting the word [partner] for [friends, family] for those particular items. Thus, there were 12 items total. A sample item is, “How often does your [partner, parents, friends] criticize you about your weight or shape?” Item responses are on a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (never) and 6 (all the time). Higher scores are indicative of greater criticisms. Internal consistencies were as follows: partner criticisms (Cronbach’s α = .79), family criticisms (.88), and peer criticisms (.76). The pressures subscale of the SATAQ-III contains seven items for each family, peers, and partner, for a total of 21 items. Response options are on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (definitely disagree) to 5 (definitely agree). A sample item is, “I’ve felt pressure from [friends, family, partner] to change my appearance.” The current study adapted these items on the SATAQ to also assess for pressures from partner. The SATAQ has demonstrated content validity by its correlation with other scales which measure related constructs, such as the Eating Disorders Inventory-Drive for Thinness subscale (EDI-DT; EDI; Garner et al. 1983), r = .61, p < .01 (Heinberg et al. 1995). The pressures subscale has demonstrated validity by significantly higher scores of eating disorder (M = 39.06) and disturbed eating (M = 37.0) than control subjects (M = 23.76; Thompson et al. 2004). Internal consistencies were as follows: partner pressures (.93), family pressures (.94), and peer pressures (.92).

Given the high correlations (r’s = .60–.89) between the criticisms and pressures subscales for each interpersonal source, family pressures and family criticisms were combined into a composite variable, peer pressures and peer criticisms were combined into a composite variable, and partner pressures and partner criticisms were combined into a composite variable for the analysis. Mean scores were computed for each type of pressure and criticism. The means for each interpersonal source for both subscales (the pressures scale and criticism subscales) were summed to create these composite variables. Higher scores are indicative of greater pressures and criticisms. This was further supported by an exploratory factor analysis, which indicted that a three factor solution was the best fit to the data (KMO = .91; Bartlett’s test of spherecity Chi Square = 7197.74, p < .001). All of the items loaded as expected at .49 or higher (with no cross-loadings great than .33) on their respective subscales, which included partner pressures and criticisms, family pressures and criticisms, and peer pressures and criticisms. Internal consistencies were as follows: partner pressures and criticisms (.92), family pressures and criticisms (.96), and peer pressures and criticisms (.91).

Results

Descriptive statistics for all variables included in the hypothesized model are displayed in Table 1. As is depicted in Table 1, greater media pressures were reported than other pressures and criticisms.

A correlation matrix was computed to determine the bivariate relationships among all variables included in the model (see Table 2). Of note, both BMI and relationship length were unrelated to dieting and bulimia/food preoccupation and thus were not included in inferential analyses.

We used AMOS 19.0 to test the fit of the hypothesized model (Fig. 1) to the data (Arbuckle 1999). Error terms for the EAT-26 subscales were correlated with one another given that they were all obtained from the same measure (EAT; Garner et al. 1982) and all highly related to one another at the bivariate level (Table 2). The goodness-of-fit chi-square statistic was used to provide a test of the hypothesized model; a non-significant chi-square statistic is desirable because it indicates that there is not a significant difference between the model and the data. Several goodness of fit indices were also utilized in order to examine the fit of the model to the data. These include the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), and Root Mean Square Error Approximation (RMSEA). For the CFI and TLI, values close to .95 and higher are evidence of an appropriate fit; for the RMSEA, values close to .06 and lower are evidence of an appropriate fit (Hu and Bentler 1995; Loehlin 2004).

Initial results revealed unacceptable goodness-of-fit indices, X 2(14, N = 246) = 59.81, p < .05; CFI = .95; TLI = .89; RMSEA = .12 (Fig. 2). Therefore, modification indices provided by the program AMOS were examined and considered theoretically justifiable. Specifically, although Thompson and colleagues (1999) initially proposed a full mediation model, others have theorized and documented that a partial mediation model where internalization partially mediates the relationship between interpersonal influences and body dissatisfaction with direct paths between interpersonal pressures and body dissatisfaction (e.g., Rodgers et al. 2009; Rodgers et al. 2011). Thus, the model was revised to include additional paths from partner pressure and criticism, peer pressure and criticism, family pressure and criticism, and media pressure to body dissatisfaction and three nonsignificant paths were deleted: family pressure and criticism to internalization, friend pressure and criticism to internalization, and partner pressure and criticism to body dissatisfaction. As demonstrated by the goodness-of-fit indices, the revised and final model was a good fit to the data (See Fig. 3), X 2(13, N = 246) = 13.87, p = . 38; CFI = 1.00; TLI = 1.00; RMSEA = .02. The final model accounted for 61 % of the variance in internalization, 53 % of the variance in body dissatisfaction, 50 % of the variance in dieting, and 18 % of the variance in bulimia/food preoccupation. As hypothesized, media weight-related pressure and partner weight-related pressures and criticism were related to internalization of the thin ideal. As hypothesized, internalization of the thin ideal was positively related to body dissatisfaction and resultant disordered eating through body dissatisfaction. Family and peer pressures and criticisms and media pressure were directly related to body dissatisfaction, which was not initially hypothesized.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to examine the tripartite influence model (Thompson et al. 1999) with the inclusion of romantic partners in college women. This study contributes to the literature in that no published study has examined the tripartite influence model with the inclusion of romantic partners in college women, which is critical when considering the growing importance of romantic partners for college women. Overall, the results of the current study support a modified version of the tripartite influence model with U.S. college students, similar to that found without the inclusion of romantic partners by other studies with college women in Australia and Japan (Rodgers et al. 2011; Yamamiya et al. 2008). Of note, examination of the descriptive statistics show that women reported almost twice as great of media pressures than other sociocultural influences. Given the media-saturated world college women live in (Neilson 2012), it is not surprising that media pressure was found to be an important predictor of internalization and body dissatisfaction. In fact, Yamamiya et al. (2005) found that even a 5 min exposure to media containing the thin-ideal, compared to neutral media, can produce a negative body image in U. S. college women in an experimental study. These effects are likely even more pronounced with continued exposure to certain types of media. This is consistent with findings from Hargreaves and Tiggemann (2003) that the more media promoting the thin-ideal that an individual views, the greater their body dissatisfaction. Assessing for quantity and type of media consumption as well as pressures in U.S. college women presenting with body image problems and disordered eating is critical.

Although media pressures were a correlate of internalization and body dissatisfaction, other social pressures and criticisms emerged as important in the model. The finding that peer criticism and pressure showed an important influence on body dissatisfaction in the model is consistent with previous research (Rodgers et al. 2011). Unique to this study, results indicated that romantic partner criticism and pressure are an important albeit small influence in the tripartite influence model in college women, consistent with findings with adolescent girls (Schomaker and Furman 2009). This is influence is possibly due to both the increased time spent with romantic partners as well as the increased importance of romantic partners during this development period. Importantly, this finding should alert clinicians to the likelihood that romantic partners, in some instances, contribute to women’s disordered eating. Thus, clinicians should screen for all, including romantic partner, sources of interpersonal weight-related pressure and criticisms. It should be noted that the relatively small influence of romantic partner influence documented in the current study could be attributed to a restricted range or selection bias, as women in more critical relationships may have been less likely to volunteer for participation in a study on relationships. It is also possible that college women are continuing to develop and family members and peers remain a more important source of support and feedback than romantic. Although romantic partner relationship length was not related to the variables of interest in the current study, it is also possible duration of these relationships plays a role in their salience to women’s body dissatisfaction. In other words, women have been exposed to weight-related pressures and criticisms from the media, family members, and peers for a greater length of time than influences from one’s romantic partner. Results from the current study also showed that the influence of partner criticism and pressure was mediated by internalization of the thin ideal. Thus, it appears that weight-related feedback from romantic partners is especially harmful for women with high pre-existing levels of internalization. Overall, it appears that social pressures and criticisms should be considered as playing an important however small role in women’s internalization and body dissatisfaction.

Results also indicated that peer and familial pressure and criticism were directly related to body dissatisfaction rather than mediated by internalization, which was not initially hypothesized. Although further research is needed to replicate this model, it appears that the mechanisms by which family and peer weight-related criticism and pressure influence women’s body satisfaction might differ by age (Rodgers et al. 2011). One possible mediator of the relationship between family and peer weight-related pressure and criticism and body dissatisfaction in this development period is self-objectification, or viewing one’s body through an observer’s perspective and monitoring one’s body shape (Fredrickson and Roberts 1997). Research has supported self-objectification as a mediator between weight-related comments (not from a particular source) and body dissatisfaction in college women (Calogero et al. 2009). Further research is necessary to determine if self-objectification serves as a path between sociocultural influences and body dissatisfaction in the tripartite model in U.S. heterosexual college women. It is important to note that although internalization was not related to all sociocultural influences in the model, it has been shown to be prospectively related to changes in both body satisfaction and eating disturbances (for a review, see Thompson and Stice 2001).

Results from the current study indicated that body dissatisfaction, as predicted by family peer, and media influences and internalization of the thin ideal, accounted for 50 % of the variance in dieting. Dieting behavior is critical to consider when considering that recent prospective research has shown that dieting behavior predicted eating disorders even among U.S. women who were satisfied with their bodies (Stice et al. 2011). Results from the current study also indicated that the tripartite model accounted for less (although significant) variability in bulimic behaviors (18 %). In addition to body dissatisfaction, it is possible that other sociocultural variables not assessed in the current study are related to bulimic behaviors. For example, experience of familial abuse has been related to the later development of bulimic behavior among U.S. college women (Fischer et al. 2010).

There are considerations that should be noted when interpreting the results. The sample was homogeneous, in terms of age, race, sexual orientation, and socioeconomic status, which limit the generalizability of the results to more diverse college women; future research should therefore include more diverse samples. The lack of variability in the predictor variables – most notably pressure and criticisms from partners and peers – is also noteworthy. Recent research has also suggested that weight status may also influence the frequency and type (positive or negative) of weight-related comments received (Herbozo et al. 2013). Although women did report a range of weights in the current study, the average BMI fell within the normal range. Further research should investigate these relationships in samples of women with diversity of weight and shape. It is also possible that frequency of weight-related comments is relatively low in college romantic couples but is more common in longer term couples (e.g., 10 or 20 year relationships). Further research should explore how relationship qualities (e.g., satisfaction) contribute to frequency of weight-related comments. It should also be noted that the current study utilized a cross-sectional design and all measures were self-report; future research should utilize longitudinal, prospective designs in order to better understand the temporal sequencing of these variables, which would allow for stronger causal inferences. Given that research has shown that Canadian women perceive their peers as having similar body image concerns (Wasylkiw and Williamson 2013), future research should collect data directly from important family members and peers. Finally, the tripartite model also theorizes that appearance comparison may serve as a mediator between sociocultural influences and body dissatisfaction (Thompson et al. 1999); future research investigating this model with the inclusion of romantic partners should also include this.

The results of the current study underscore the need for future research examining the mechanisms by which the media affects college women’s body image and dissatisfaction levels. However, given the large obstacles in advocating for societal-level changes in media depictions of women, it crucial that we develop and implement individual-level media-focused interventions on college campuses, which may have larger potential for immediate change (Stice and Shaw 2002). Although many interventions have been found to be only modestly effective as mentioned above (Stice et al. 2007), prior research on media-focused interventions has indicated that media literacy and dissonance interventions, that is efforts that focus on persuasion that media images are not real, are most effective (Stice et al. 2008; Yager and O’Dea 2008). University campuses provide an optimal setting to provide these empirically supported prevention and intervention programs given the ability to reach a large number of women in a cost-effective manner (Yager and O’Dea 2008). Additionally, results from the current study as well as recent research (Wasylkiw and Williamson 2013) underscore the need to also consider pressures and criticisms from important individuals – in the current study family, peers, and partners –when developing psychoeducation campaigns and programming. As peers often share norms for body image and eating behaviors, Keel and Forney (2013) note that peers may represent a key opportunity to intervene in preventing the development of eating disorders. Peer group-based interventions may allow college personnel to target shared norms for body image and eating behaviors by altering the discussions that occur between college women. In conclusion, it is critical that we continue to better understand the factors that shape college women’s levels of body dissatisfaction and create effective ways to promote social- and individual-level change.

References

Arbuckle, J. (1999). Amos user’s guide, version 4.0. Chicago: Marketing Division SPSS Inc: Small Waters Corporation.

Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

Befort, C., Kurpius, S. E. R., Hull-Blanks, E., Nicpon, M. F., Huser, L., & Sollenberger, S. (2001). Body image, self-esteem, and weight-related criticism from romantic partners. Journal of College Student Development, 42, 407–419.

Calogero, R. M., Herbozo, S., & Thompson, J. K. (2009). Complimentary weightism: The potential costs of appearance-related commentary for women’s self-objectification. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 33, 120–132. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2008.01479.x.

Cash, T. F., Ancis, J. R., & Strachan, M. D. (1997). Gender attitudes, feminist identity, and body images among college women. Sex Roles, 36, 433–447. doi:10.1007/BF02766682.

Cooper, P. J., Taylor, M. J., Cooper, Z., & Fairburn, C. G. (1987). The development and validation of the body shape questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 6, 485–494. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198707)6:4<485::AID-EAT2260060405>3.0.CO;2-O.

Eisenberg, M. E., Berge, J. M., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2013). Dieting and encouragement to diet by significant others: Associations with disordered eating in young adults. American Journal of Health Promotion, 27, 370–377. doi:10.4278/ajhp.120120-QUAN-57.

Fischer, S., Stojek, M., & Hartzell, E. (2010). Effects of multiple forms of childhood abuse and adult sexual assault on current eating disorder symptoms. Eating Behaviors, 11, 190–192. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2010.01.001.

Forbes, G. B., Jung, J., Vaamonde, J. D., Omar, A., Paris, L., & Formiga, N. S. (2012). Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in three cultures: Argentina, Brazil, and the U. S. Sex Roles, 66, 677–694. doi:10.1007/s11199-011-0105-3.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T. (1997). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

Garner, D. M., Olmsted, M. P., Bohr, Y., & Garfinkel, P. E. (1982). The eating attitudes test: Psychometric features and clinical correlates. Psychological Medicine, 12, 871–878. doi:10.1017/S0033291700049163.

Garner, D. M., Olmstead, M. P., & Polivy, J. (1983). Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 2, 15–34. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(198321)2:2<15::AID-EAT2260020203>3.0.CO;2-6.

Grabe, S., Ward, J. S., & Ward, L. M. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 460–476. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460.

Groesz, L. M., Levine, M. P., & Murnen, S. K. (2002). The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta‐analytic review. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31, 1–16. doi:10.1002/eat.10005.

Grossbard, J. R., Neighbors, C., & Larimer, M. E. (2011). Perceived norms for thinness and muscularity among college students: What do men and women really want? Eating Behaviors, 12, 192–199. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2011.04.005.

Hargreaves, D., & Tiggemann, M. (2003). Longer-term implications of responsiveness to ‘thin ideal’ television: Support for a cumulative hypothesis of body image disturbance? European Eating Disorders Review, 11, 465–477. doi:10.1002/erv.509.

Heinberg, L. J., Thompson, J. K., & Stormer, S. (1995). Development and validation of the sociocultural attitudes toward appearance questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 17, 81–89. doi:10.1002/1098-108X(199501)17:1<81::AID-EAT2260170111>3.0.CO;2-Y.

Herbozo, S., Menzel, J. E., & Thompson, J. K. (2013). Differences in appearance-related commentary, body dissatisfaction, and eating disturbance among college women of varying weight groups. Eating Behaviors, 14, 204–206. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2013.01.013.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1995). Evaluating model fit. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications (pp. 76–99). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Jones, W., & Morgan, J. (2010). Eating disorders in men: A review of the literature. Journal of Public Mental Health, 9, 23–31. doi:10.5042/jpmh.2010.0326.

Keel, P. K., & Forney, K. J. (2013). Psychosocial risk factors for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46, 433–439. doi:10.1002/eat.22094.

Krones, P. G., Stice, E., Batres, C., & Orjada, K. (2005). In vivo social comparison to a thin ideal peer promotes body dissatisfaction: A randomized experiment. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 38, 134–142. doi:10.1002/eat.20171.

Loehlin, J. C. (2004). Latent variable modeling: An introduction to factor, path, and structural equation modeling (5th ed.). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

McCarthy, M. (1990). The thin ideal, depression and eating disorders in women. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 28, 205–214. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(90)90003-2.

Menzel, J. E., Schaefer, L. M., Burke, L. N., Mayhew, L. L., Brannick, M. T., & Thompson, J. K. (2010). Appearance-related teasing, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. Body Image, 7, 261–270. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.05.004.

Miller, M. K., & Summers, A. (2007). Gender differences in video game characters’ roles, appearances, and attire portrayed in video game magazines. Sex Roles, 57, 733–742. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9307-0.

Mintz, L. B., & O’Halloran, M. S. (2000). The eating attitudes test: Validation with DSM-IV eating disorder criteria. Journal of Personality Assessment, 74, 489–503. doi:10.1207/S15327752JPA7403_11.

Morrison, K. R., Doss, B. D., & Perez, M. (2009). Body image and disordered eating in romantic relationships. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 28, 281–306. doi:10.1521/jscp.2009.28.3.281.

Neilson. (2012). State of the media spring 2012: Advertising and audiences. Part 2: By demographic. New York, NY: The Neilson Company. Retrieved from http://nielsen.com/content/dam/corporate/us/en/reports-downloads/2012-Reports/nielsen-advertising-audiences-report-spring-2012.pdf.

Rodgers, R., Chabrol, H., & Paxton, S. J. (2011). An exploration of the tripartite influence model of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among Australian and French college women. Body Image, 8, 208–215. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2011.04.009.

Rodgers, R., Paxton, S. J., & Chabrol, H. (2009). Effects of parental comments on body dissatisfaction and eating disturbance in young adults: A sociocultural model. Body Image, 6, 171–177. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.04.004.

Schomaker, L. B., & Furman, W. (2009). Interpersonal influences on late adolescent girls’ and boys’ disordered eating. Eating Behaviors, 10, 97–106. doi:10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.02.003.

Shapiro, J. P., Baumeister, R. F., & Kessler, J. W. (1991). A three-component model of children’s teasing: Aggression, humor, and ambiguity. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 10, 459–472. doi:10.1521/jscp.1991.10.4.459.

Silberstein, L. R., Striegel-Moore, R. H., Timko, C., & Rodin, J. (1988). Behavioral and psychological implications of body dissatisfaction: Do men and women differ? Sex Roles, 19, 219–232. doi:10.1007/BF00290156.

St. Peter, C. (1997). Marital quality and psychosocial determinants of self-esteem and body image of mid-life women (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Arizona State University, Phoenix, AZ.

Stice, E., Marti, C. N., & Durant, S. (2011). Risk factors for the onset of eating disorders: Evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behavior Research and Therapy, 49, 622–627. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.009.

Stice, E., & Shaw, H. E. (2002). Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology. A synthesis of research findings. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 985–993. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9.

Stice, E., Shaw, H., Becker, C. B., & Rohde, P. (2008). Dissonance-based interventions for the prevention of eating disorders: Using persuasion principles to promote health. Prevention Science, 2, 114–128. doi:10.1007/s11121-008-0093-x.

Tanner, J. L. (2012). Emerging adulthood. In R. J. R. Levesque (Ed.), Encyclopedia of adolescence (pp. 818–825). New York: Springer.

Tester, M. L., & Gleaves, D. H. (2005). Self-deceptive enhancement and family environment: possible protective factors against internalization of the thin ideal. Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention, 13, 187–199. doi:10.1080/10640260590919071.

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington: American Psychological Association.

Thompson, J. K., & Stice, E. (2001). Thin ideal internalization: Mounting evidence for a new risk factor for body-image disturbance and eating pathology. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10, 181–183. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00144.

Thompson, J. K., van den Berg, P., Roehrig, M., Guarda, A. S., & Heinberg, L. J. (2004). The sociocultural attitudes toward appearance scale-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35, 293–304. doi:10.1002/eat.10257.

Tiggemann, M. (2005). Body dissatisfaction and adolescent self-esteem: Prospective findings. Body Image, 2, 129–135. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.03.006.

Van den Berg, P., Thompson, J. K., Obremski-Brandon, K., & Coovert, M. (2002). The tripartite influence model of body image and eating disturbance: A covariance structure modeling investigation testing for the mediational role of appearance comparison. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 1007–1020. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00499-3.

Wasylkiw, L., & Williamson, M. E. (2013). Actual reports and perceptions of body image concerns of young women and their friends. Sex Roles, 68, 239–251. doi:10.1007/s11199-012-0227-2.

Wolf, N. (1991). The beauty myth: How images of beauty are used against women. New York: Random House.

Yager, Z., & O’Dea, J. A. (2008). Prevention programs for body image and eating disorders on university campuses: A review of large, controlled interventions. Health Promotion International, 23, 173–189. doi:10.1093/heapro/dan004.

Yamamiya, Y., Cash, T. F., Melnyk, S. E., Posavac, H. D., & Posavac, S. S. (2005). Women’s exposure to thin-and beautiful media images: Body image effects of media-ideal internalization and impact reduction interventions. Body Image, 2, 74–80. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.11.001.

Yamamiya, Y., Shroff, H., & Thompson, J. K. (2008). The tripartite influence model of body image and eating disturbance: A replication with a Japanese sample. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41, 88–91. doi:10.1002/eat.20444.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Johnson, S.M., Edwards, K.M. & Gidycz, C.A. Interpersonal Weight-Related Pressure and Disordered Eating in College Women: A Test of an Expanded Tripartite Influence Model. Sex Roles 72, 15–24 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0442-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-014-0442-0