Abstract

Despite evidence that middle adolescent girls (ages 14–17) experience more body dissatisfaction than early adolescent girls (ages 10–13) or boys at these ages, researchers have rarely considered whether such differences are observed regarding factors related to body dissatisfaction, particularly within non-Western samples. To address this issue, gender and age group differences in media and interpersonal influences on body dissatisfaction were assessed among early and middle adolescents living in Chongqing, China. In Study 1, 595 boys and 648 girls completed self report measures of demographics, public self-consciousness and appearance-based social pressure, comparisons, and conversations. Compared to boys, girls reported more appearance pressure from mass media and close interpersonal networks (friends, family), appearance comparisons with peers, and appearance conversations with friends; these effects were qualified by interactions with age group, indicating media and interpersonal factors were more prominent in the lives of middle adolescent girls than other groups. Effects were observed independent of body mass index (BMI) and public self-consciousness. In Study 2, 738 girls and 661 boys completed the same measures and a body dissatisfaction scale. By and large, gender and age differences were replicated. Middle adolescent girls also reported more body dissatisfaction than peers did. Perceived appearance pressure from mass media and interpersonal ties were both implicated in mediation analyses to explain this gender × age group effect.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Body dissatisfaction is pervasive during adolescence, especially among girls (e.g., Thompson et al. 1999; Wertheim et al. 2009). For example, gender differences in body dissatisfaction have been documented among Western adolescents including American 13–19 year olds (e.g., Ata et al. 2007; Jones and Crawford 2006), 11–17 year old Australians (Vincent and McCabe 2000), French 16 year olds (e.g., Rodgers et al. 2009), Irish 12–18 year olds (Lawler and Nixon 2011), and Swiss 14–16 year olds (e.g., Knauss et al. 2008). Such differences extend to adolescents in Asian nations including 12–15 year olds in South Korea (Jung et al. 2009) and 12–19 year olds in mainland China (Chen and Jackson 2009; Chen et al. 2006; Xie et al. 2006).

In light of the social, cognitive, and physical changes that occur between early (ages 10–13), middle (ages 14–17), and late (ages 18–21) phases of adolescence (Steinberg 2007), such gender differences might vary as a function of age. Indeed, researchers from both the United States (e.g., Bearman et al. 2006; Presnell et al. 2004; Rosenblum and Lewis 1999) and China (e.g., Chen and Jackson 2008; Chen et al. 2006) have found body dissatisfaction to be higher for middle adolescent girls than early adolescent girls. Conversely, body dissatisfaction levels of boys in these samples were quite stable across these age groups, albeit other research has observed 15 year old American boys report less body satisfaction than do 10 year old boys on the cusp of adolescence (e.g., Paxton et al. 2006).

Because specific mass media and interpersonal factors contribute to body dissatisfaction (e.g., Stice 2001; Thompson et al. 1999), it is plausible that such factors also help to explain middle adolescent girls’ increased susceptibility to body dissatisfaction relative to early adolescent girls or boys in the same age groups. Given that body dissatisfaction is a risk factor for eating disorders and emotional distress (Jacobi et al. 2004; Stice 2001) and because eating concerns typically peak in middle adolescence (American Psychiatric Association 2000), examining “critical” developmental windows wherein appearance-based media and interpersonal factors exert their strongest effects may aid in identifying more and less vulnerable subgroups and facilitate early interventions to reduce or prevent body image and eating disturbances.

To address this issue, gender and age group differences in select media and interpersonal correlates of body dissatisfaction were assessed in two samples of Chinese adolescents. Specifically, Study 1 examined differences between early and middle adolescent Chinese girls and boys on measures of appearance-based pressure from mass media and close interpersonal networks, social comparisons, and conversations. In Study 2, the stability of obtained gender × age group differences was evaluated in a new sample as were mediating effects of mass media and interpersonal factors on gender and gender × age differences in body dissatisfaction.

Sociocultural Accounts of Body Dissatisfaction

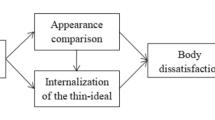

In explaining the development of body dissatisfaction, sociocultural models initially tested within American samples have emphasized mass media, family, and peers as purveyors of societal messages about physical appearance and attractiveness ideals, particularly for females (e.g., Stice 2001; Thompson et al. 1999). Pressure to alter one’s appearance or adopt unrealistic feminine or masculine standards of attractiveness such as ultra-thinness or hyper-muscularity can be expressed through explicit messages from parents, peers, and mass media as well as innocuous experiences such as conversations with friends about clothes, looks, and attractiveness that convey expectations about physical appearance (e.g., Jones et al. 2004). Sociocultural theorists also posit that appearance pressure contributes to body dissatisfaction both directly and indirectly through increasing preferences of unrealistic attractiveness standards and the frequency of appearance comparisons with peers and media ideals (Jones 2004; Thompson et al. 1999).

Associated Research on Western Adolescent Samples

Empirically, appearance pressure from one or both parents has been found to predict body dissatisfaction or eating disturbances in adolescent girls and boys from France (Rodgers et al. 2009), Australia (e.g., Vincent and McCabe 2000), and the United States (e.g., Field et al. 2001). Appearance pressure from friends or peers also correlates with body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls (e.g., Ata et al. 2007; Shroff and Thompson 2006) and boys (e.g., Vincent and McCabe 2000). Consistent with the proposition that peer relations become increasingly important with the onset of adolescence (Steinberg 2007), some authors have reported that appearance pressure or feedback has stronger links to body image concerns of both 10–15 year old (Shroff and Thompson 2006) and 16–19 year old (Presnell et al. 2004) American adolescents than do appearance messages of parents.

General reviews have also concluded that pressure communicated through exposure to mass media portrayals of physical attractiveness contributes to body dissatisfaction for Western females (Grabe et al. 2008) and males (Barlett et al. 2008). In fact, mass media may be an overarching influence that promotes idealized attractiveness standards embraced by peers, parents and the self (Thompson et al. 2004). In studies with adolescents, perceived pressure from mass media has been found to directly predict body image and eating concerns among 10–18 year old girls (Hargreaves and Tiggemann 2004; Knauss et al. 2008; Shroff and Thompson 2006; Warren et al. 2010). Media pressure has been linked to body dissatisfaction among adolescent boys as well (Knauss et al. 2008), albeit null effects have been reported too (Hargreaves and Tiggemann 2004; Humphreys and Paxton 2004).

Frequent appearance comparisons and conversations with friends are other potentially important influences on body dissatisfaction. For example, Jones (2001) found that more frequent appearance comparisons corresponded to higher levels of body dissatisfaction in American samples of adolescent girls and boys. Jones et al. (2004) noted how appearance conversations draw attention to body image concerns, promote social comparisons with certain standards of attractiveness, and reinforce the importance of appearance within friendships. These authors observed adolescent girls and boys who had frequent appearance conversations were more prone to body dissatisfaction. Moreover, Jones (2004) found prospective effects of appearance comparisons and conversations on body dissatisfaction increases over time, albeit only among adolescent girls.

Notwithstanding evidence that appearance pressure, conversations, and comparisons correlate with body dissatisfaction, gender differences in these experiences are quite common. For example, compared to boys, adolescent girls report more pressure directed at shape, weight, and weight loss from parents (e.g., Ata et al. 2007; Rodgers et al. 2009; Vincent and McCabe 2000) and peers (Ata et al. 2007). At the same time, boys report relatively more pressure from friends and family to gain muscle (e.g., Ata et al. 2007; McCabe and Ricciardelli 2005). Media portrayals also communicate subtle or explicit expectations about gender-based appearance. For example, heavier than average adults, especially women, are under-represented in American television sitcoms (Fouts and Burggraf 2000; Fouts and Vaughan 2002), findings that imply media messages about acceptable appearance target females more strongly than males. Gender differences in media pressure targeting body weight and shape (Knauss et al. 2008; Warren et al. 2010) may be due, in part, to heightened pressure on females to conform to idealized images (Knauss et al. 2008). Girls are more likely to discuss appearance in general with friends (e.g., Jones and Crawford 2006; Jones et al. 2004; Lawler and Nixon 2011), but boys may discuss muscle-building with friends more often than girls discuss dieting (Jones and Crawford 2006). Finally, American studies have found girls engage in appearance comparisons more than boys do (e.g., Jones 2001; Schutz et al. 2002; Warren et al. 2010).

Limitations of Associated Research

Most of the studies reviewed above focused solely on overall gender differences so the contention that heightened body dissatisfaction among middle adolescent girls is accompanied by relative elevations in associated interpersonal and media factors was not evaluated directly. While Jones’ (2004) study indicated tenth grade girls had higher average levels of body dissatisfaction, appearance comparisons and appearance conversations than did seventh grade girls or boys in either grade, gender × age group effects were not assessed because scale factor structures were not entirely consistent for girls and boys. As a result, the hypothesis that these experiences are more prominent among middle adolescent girls requires formal evaluation.

Furthermore, to demonstrate that social-environmental correlates of body dissatisfaction vary between subgroups of adolescents, effects should be observed independent of normative physical and cognitive changes that (1) occur between early and middle adolescence and (2) also correlate with body dissatisfaction. The most prominent physical change that occurs during adolescence and corresponds with body dissatisfaction is an increase in body mass index (BMI), a height to weight ratio used to define weight status. Because BMI increases clash with the feminine attractiveness ideal of thinness, many girls experience exacerbations in weight and body dissatisfaction as the gap actual and ideal weight widens (Bearman et al. 2006). Conversely, among boys, BMI increases can converge with masculine appearance ideals regarding larger size and muscularity, hence potentially increasing boys’ satisfaction with weight and shape (Bearman et al. 2006), although this association may be less applicable to currently overweight boys (e.g., Jones and Crawford 2006).

Public self-consciousness is a cognitive-developmental correlate of body dissatisfaction that typically increases during adolescence (Frankenberger 2000) as brain regions that process social information mature (Nelson et al. 2005). Perceptions that one’s appearance and behavior are the focus of others’ attention may not abate in adulthood and can intensify over time, particularly for girls and young women (McKinley 1999). Among young females, adoption of an outsider’s perspective in judging one’s body decreases body esteem and increases body image concerns (McKinley 1999; Striegel-Moore et al. 1993). In sum, controlling for developmental factors including BMI and public self-consciousness may help to demonstrate how gender and age-group differences in interpersonal and media correlates of body dissatisfaction reflect variations in social environments of adolescents.

Finally, research on gender differences in media and interpersonal correlates of body dissatisfaction has typically focused on American, European, and Australian adolescents. Hence, it is not clear whether these experiences are unique to Western adolescents or extend to samples in Asian countries where rates of body image and eating disturbances are comparable to those found in traditionally at risk groups such as Caucasian girls and women (see Wildes and Emery 2001). This lack of knowledge may be most apparent in densely populated rapidly developing countries such as China wherein eating and body image problems are increasing among children and adolescents (Chen and Jackson 2008; Jackson and Chen 2010a; Li et al. 2005) and research linking such concerns to media and interpersonal factors has only recently emerged (e.g., Chen et al. 2007; Jackson and Chen 2008a, b; Xie et al. 2006). Further consideration of marginalized cultural groups in research can both elucidate facets of sociocultural models that are unique to particular cultures or more universal and reduce stigmatization when group members present with concerns (Striegel-Moore and Bulik 2007). The small body of related work on mainland Chinese adolescents is reviewed below as a foundation for the current study.

Research on Media and Interpersonal Correlates of Body Dissatisfaction Among Chinese Adolescents

During the past decade, tenets of sociocultural models have been linked to body image and eating disturbances of Chinese adolescents. Failure to attain unrealistic socially-prescribed attractiveness ideals such as ultra-thinness for females or a mesomorphic or hyper-muscular build for males is central to sociocultural accounts (e.g., McCabe and Ricciaredelli 2004; Thompson et al. 1999). Similar to Western nations such as the United States, thinness is a feminine attractiveness ideal in China. Leung et al. (2001) contend this ideal did not arise in China recently as a result of Westernization but instead has been rooted in Chinese history for centuries as highlighted in classical literature and art, practices and dress. To illustrate, waist and foot binding were practiced for thousands of years to achieve tiny waists and feet, two bodily features central to feminine beauty in ancient China and signs of a privileged background for women in contrast to plumpness, an ideal preferred in lower socioeconomic groups. As a more contemporary example, since the early 1900s, the national costume for Chinese women has been the “Chi-pao,” a long thin dress that wraps tightly around the body to enhance a slim, curvaceous figure (Leung et al. 2001). Recent studies of adolescent Chinese girls have found stronger preferences for a thin ideal predict body dissatisfaction (Chen et al. 2007; Li et al. 2005), losses of weight esteem (Chen and Jackson 2009) and increases in disordered eating over time (Jackson and Chen 2008c, d).

Conversely, the status of muscularity as a masculine ideal for males of Chinese descent is ambiguous. On one hand, evidence that mainland Chinese boys engage in muscle-building activities to a degree similar to Australian boys suggests comparable levels of drive for muscularity between these groups (Xu et al. 2010). Conversely, Jung et al. (2010) found emerging adult men from Hong Kong are more satisfied with their muscularity, have a lower drive for muscularity, and endow muscularity with fewer positive attributes than American men do. These authors and others (e.g., Yang et al. 2005) assert males of Chinese descent prefer masculine ideals that emphasize cerebral, scholarly qualities as well as physical traits like aggression.

If this evidence suggests attractiveness ideals posited in traditional sociocultural accounts are more clearly applicable to Chinese females than males, other research has confirmed that appearance-based social pressure and comparisons are relevant to body image concerns of Chinese samples. A collectivist value orientation and emphasis on developing one’s guanxiwang or network of social connections in China can foster awareness of expected standards for appearance and behavior and willingness to adopt others’ preferences in the service of interpersonal harmony (Smart 1999). As Jung and Lee (2006) have written, a highly collectivist orientation promotes sensitivity to others’ feedback about one’s physical appearance and efforts to reduce deviance from accepted appearance norms through engaging in appearance-based social comparisons.

Empirically, exposure to mass media, particularly from other Asian countries, has been linked to weight dissatisfaction among Chinese girls in grades 7–11 (Xie et al. 2006). In causal modeling research, elevations on a composite scale of media, family, and friend appearance pressure and BMI both had significant, direct paths with fatness concerns of 12–22 year olds within each gender. Reported appearance pressure and frequent appearance comparisons also predicted fatness concerns within early, middle, and late adolescent males and females, independent of significant effects of BMI and related appearance concerns (Jackson and Chen 2008a, b). Xu et al. (2010) found pressure from adults, peers, and mass media to lose weight each contributed to body dissatisfaction among 12–16 year old girls, independent of BMI. Pressure from adults and peers to lose weight correlated with body dissatisfaction among boys of the same age too, but not to a statistically significant degree.

This work illustrates how associations of appearance pressure and comparisons to body dissatisfaction in Chinese adolescents parallel those of peers in Western countries. Regardless, few researchers have directly examined gender and age group differences. Xu et al. (2010) found girls reported more body dissatisfaction and pressure from media to lose weight than boys did as well as less pressure from media, peers, and adults to gain muscle. While these authors did not observe gender differences in interpersonal pressure to lose weight, one study found girls score higher on a composite measure of media and interpersonal pressure (Chen and Jackson 2009). Other research indicated girls report comparatively more general appearance pressure, social comparisons with peers and appearance conversations with friends (Jackson and Chen 2011). Age group differences have not been central to studies of Chinese samples but select research has indicated BMI, appearance pressure, and appearance comparison levels are lower among 12–13 year olds than 16–17 year olds, albeit gender × age effects were only marginally significant (Chen and Jackson 2009).

Study 1

Based on the preceding review, this study evaluated differences in interpersonal and mass media experiences related to body dissatisfaction among early and middle adolescent Chinese boys and girls. Given consistent gender differences on these factors among Western adolescents (e.g., Ata et al. 2007; Jones et al. 2004; Knauss et al. 2008) and emerging evidence for gender differences among Chinese adolescents (e.g., Chen and Jackson 2009; Xu et al. 2010), we hypothesized that girls would report more general appearance pressure from media and close interpersonal contacts, appearance conversations with friends and appearance comparisons with peers than would boys.

Few of the reviewed studies explored gender × age group interactions, yet appearance pressure, comparisons and conversations were linked with adolescent body dissatisfaction in each cultural context. These associations coupled with evidence that middle adolescent girls from both the U.S. and China report more body dissatisfaction than early adolescent girls or boys in these age groups were foundations for a second hypothesis: middle adolescent girls would report significant elevations on interpersonal and media factors relative to seventh grade girls while tenth and seventh grade boys would not differ on these measures. Finally, assuming that social environments of groups under study vary on the basis of interpersonal and media experiences that promote body dissatisfaction, hypothesized gender × age group interactions were tested after controlling for potential physical and cognitive correlates of body dissatisfaction, BMI and public self-consciousness.

Method

Participants and Procedure

The final sample included 11–13 year old early adolescents (304 boys, 320 girls) and 15–17 year old middle adolescents (291 boys, 328 girls) recruited from grade seven and ten classes of two schools in Chongqing, China. The sample had an average age of 14.50 years (SD = 1.87) and was largely Han in ethnicity (97.0%); remaining students were Tu (1.5%), Maio (0.9%) or from one of five other ethnic minorities. There were no gender or age group differences in ethnicity (p’s > .21). Based on self-reports, the mean BMI was 19.37 (SD = 2.96); only 4.0% of students had a BMI above 25.

After receiving ethics approval from Southwest University (SWU), Chongqing, the first author received school permissions to conduct the study. Informed consent was obtained from participating teachers and parents/legal guardians of eligible children. Teachers gave research volunteers a survey packet, including an informed consent outlining the general research focus, time involved (30 min), and the voluntary, anonymous nature of participation. Measures were presented next followed by referral details for those distressed by body image concerns. Students were encouraged to read items carefully and return completed surveys to teachers separately from informed consents. Thirty-seven surveys were eliminated because over missing data (>5.0%). Mean substitutions were used to address missing data in retained surveys. Data collection occurred during March, 2008.

All scales were translated previously into Chinese and back-translated into English by two Ph.D. students majoring in English at SWU. Translators and the second author discussed minor deviations in meaning and modified them to better approximate meanings of original scales. Items related to appearance pressure and public self-consciousness scales were subjected to principal components analyses (PCA) within each gender. Original factor structures of other measures had been replicated previously in samples of Chinese girls and boys (Chen and Jackson 2009; Jackson and Chen 2008c, 2010a). All Kaiser–Meyer–Oklin values exceeded .78 and the conventional threshold (.60). Corresponding Bartlett’s tests were significant (p < .001). The scales are included as an Appendix.

Measures

Perceived Sociocultural Pressure Scale (PSPS; Stice and Agras 1998)

The eight-item PSPS taps appearance pressure from friends, family, prospective dating partners, and mass media. In this research, the six interpersonal items were rated between “1 = Not at all” and “5 = Very Much” and summed to obtain total scores. Stice and Agras (1998) concluded the PSPS has acceptable psychometrics. In this study, PCA obtained unidimensional structures comprised of all items that explained 54.74% and 57.07% of the scale variance for boys and girls, respectively. Corresponding reliabilities were α = .89 for girls and α = .87 for boys.

Mass Media Pressure

The seven-item Pressures subscale of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 (SATAQ-3; Thompson et al. 2004) examined pressure from television, movies, and magazines to conform to media portrayals of physical appearance. Items were rated on a 5-point scale of agreement and summed to attain scale totals. Slight modifications were made to ensure items were gender-neutral (e.g., “I’ve felt pressure to look pretty” modified to “to look attractive”). The subscale has satisfactory reliability and validity in Western samples (e.g., Thompson et al. 2004). However, for each gender in this sample, six items loaded on a single component, explaining 49.10% and 56.78% of the scale variance for boys and girls, respectively. The excluded item, “I’ve felt pressure from TV or magazines to exercise” failed to load for girls and loaded alone on a unique factor for boys. Alphas for media pressure were α = .89 for girls and α = .84 for boys.

Appearance Conversations with Friends (Jones et al. 2004)

This five item scale assessed how often students discussed physical appearance with friends. Items were rated between “1 = Not at all” and “5 = Very often” and added to achieve total scores. The scale has univariate structures comprised of all items in American (Jones 2004) and Chinese (Jackson and Chen 2010a) samples. Appearance conversation items had alphas of α = .90 for girls and α = .87 for boys.

Physical Appearance Comparison Scale-Revised (PACS; Shroff and Thompson 2006)

Four items assessed tendencies to compare one’s appearance to that of others. Response options, ranging from “1 = Never” to “5 = Always”, were summed across items for a total score. The PACS is internally consistent, and reliably related to body dissatisfaction and disordered eating in American (e.g., Shroff and Thompson 2006; Thompson et al. 1999) and Chinese (Jackson and Chen 2007, 2008c) samples. Alphas were α = .88 for girls and α = .84 for boys.

Public Self-Consciousness Scale (PSCS; Fenigstein et al. 1975)

This seven-item scale assessed awareness of others’ reactions to the self and appearance. Items were rated between “1 = not at all” and “5 = very much so” and summed to attain total scores. The scale has adequate reliability and validity (e.g., Nasby 1989). Single factor solutions explaining 52.75% and 53.18% of the variance emerged in PCA for girls and boys in this sample. Alphas were α = .84 for girls and α = .85 for boys.

Background Data

Age, gender, weight, height, and ethnicity were queried. Given recent evidence of links between socioeconomic status (SES) and body image in Chinese adolescents (Chen and Jackson 2009), material SES was assessed by summing responses (“No” vs. “Yes”) regarding family ownership of 13 items (e.g., computer, dvd, car) from Shi et al.’s (2006) Chinese language scale. Alphas were α = .81 for girls and α = .84 for boys.

Results and Discussion

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and univariate F-values for the research measures. As shown there, girls and boys had lower average BMI than those found in American early and/or middle adolescents (e.g., Bearman et al. 2006; Jones 2004) and a higher material SES than that reported in Shi et al.’s (2006) research. All groups reported mean public self-consciousness scores higher than the mid-point between “Occasional” and “Some”. On average, boys and early adolescent girls reported less than “Occasional” pressure from close interpersonal networks and mass media while middle adolescent girls had slightly to moderately more than “Occasional” pressure scores. All groups reported at least “Occasional” mean appearance comparison and conversation levels, with middle adolescent girls reporting means at mid-points between “Occasional” and “Some”.

In 2 (Gender) × 2 (Age Group) analyses of variance (ANOVA), no gender differences were observed for material SES or BMI, though girls endorsed more public self-consciousness than boys did (Table 1). As expected, mean BMI and public self-consciousness levels were higher among 15–17 year olds. Unexpectedly, 11–13 year olds had a higher material SES score than did older peers. Finally, a gender × age interaction for BMI indicated younger and older boys had, respectively, higher and lower BMI levels than did younger and older girls (Table 1). Based on these analyses, material SES, BMI, and public self-consciousness were covaried in ensuing analyses.

Main Analyses

To test the hypotheses that girls would report more appearance-based pressure, comparisons and conversations than would boys, a 2 (Gender) × 2 (Age group) multivariate analysis of covariance (MANCOVA) was performed. After controlling for material SES, F (4, 1232) = 2.12, p < .06, BMI, F (4, 1232) = 30.70, p < .001, and public self-consciousness, F (4, 1232) = 195.87, p < .001, multivariate effects emerged for Gender, F (4, 1232) = 33.56, p < .001, Age, F (4, 1232) = 12.91, p < .001, and their interaction, F (4, 1232) = 8.55, p < .001. Girls scored higher than boys on all interpersonal and mass media measures but no other main effects were found for age (see Table 1).

The hypothesis that middle adolescent girls would be particularly susceptible to interpersonal and media influence was partially supported. Gender × age group interactions emerged on all dependent measures, except appearance comparisons. Bonferroni-adjusted post-hoc tests indicated 15–17 year old girls reported more appearance pressure from mass media (p < .001), interpersonal appearance pressure (p < .018) and appearance conversations (p < .001) than did younger girls. In contrast, no age differences were observed between groups of boys.

Consistent with studies of American adolescents (e.g., Ata et al. 2007; Jones 2004), adolescent girls in China experienced relatively more pressure from mass media and close social networks to change their appearance, reported more appearance comparisons with peers and focused more often on physical appearance as a topic of discussion with friends. Appearance pressure and conversations were more prominent among 15–17 year old girls than 11–13 year old girls while no age differences were noted for boys. These effects emerged independent of age differences in BMI and public self-consciousness, suggesting middle adolescent Chinese girls are susceptible to body dissatisfaction, in part, because appearance-based experiences within their social environs diverge from those of younger girls and boys.

Study 2

Gender differences in correlates of body dissatisfaction from Study 1 were consonant with body dissatisfaction differences in Western (e.g., Knauss et al. 2008; Vincent and McCabe 2000; Thompson et al. 1999) and Chinese samples (e.g., Chen et al. 2006; Xu et al. 2010). However, the reliability of gender × age group interactions was uncertain due to an absence of directly related work. Cross-validation is one strategy that helps to ensure more novel findings are not specific to one sample. Hence, one focus of Study 2 was to assess the reliability of gender × age group effects in a new sample.

Furthermore, gender and age group differences in correlates of body dissatisfaction from Study 1 implied middle adolescent Chinese girls are more prone to body dissatisfaction too. Chen and Jackson (2008) found Chinese girls and middle adolescents were respectively more likely to than boys and early or late adolescents to report fear of fatness and weight gain, view themselves as fat, and express dissatisfaction with general appearance. However, because that research used largely categorical indices and body dissatisfaction was not assessed in Study 1, presumed gender × age effects for body dissatisfaction required direct tests.

Finally, because interpersonal and mass media pressure predict body image concerns among Chinese adolescents (Chen et al. 2007; Jackson and Chen 2008a, b; Xie et al. 2006), it is plausible that these factors mediate gender and gender × age group differences in body dissatisfaction too. That is, middle adolescent girls might be especially prone to body dissatisfaction because they experience more appearance pressure than early adolescent girls or boys in either age group.

In sum, Study 2 was designed to (1) cross-validate gender × age-group differences observed in Study 1, (2) directly assess gender and age group differences in body dissatisfaction, and (3) evaluate whether possible gender and gender × age differences in body dissatisfaction were mediated by interpersonal and media factors. First, we hypothesized patterns of gender and gender × age differences on interpersonal and media measures from Study 1 would be replicated in a new sample. Second, hypothesized gender and gender × age differences in body dissatisfaction were expected to conform with evidence that American and Chinese middle adolescent girls report more body image concerns than do early adolescent girls or boys in these age groups (e.g., Bearman et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2006; Chen and Jackson 2008),. Finally, we explored the extent to which the hypothesized gender and gender × age group differences in body dissatisfaction were mediated by appearance pressure, comparisons, and conversations.

Method

Participants and Procedure

Procedures were identical to those from Study 1 except that a new sample was recruited and a body dissatisfaction scale was added to the protocol. The final sample included 11–13 year old (373 boys, 451 girls) and 15–17 year old (288 boys, 287 girls) students recruited from seventh and tenth grade classes of two different Chongqing schools. Surveys of 14 other students were eliminated due to excess missing data. The mean age of students was 14.17 years (SD = 1.82 years) with 97.2% reporting Han ethnicity; others were from Maio (0.8%), Tu (1.2%) or five other ethnic groups. Chi-square analyses revealed no gender or age group differences for ethnicity (p’s > .109). The mean BMI was 19.42 (SD = 2.84) with only 3.3% of students reporting a BMI over 25.

Measures

In the new sample, satisfactory alphas were obtained for material SES [α = .84 for girls, α = .86 for boys], public self-consciousness [α = .85 for girls, α = .85 for boys], perceived interpersonal appearance pressure [α = .86 for girls, α = .84 for boys], perceived mass media pressure [α = .90 for girls, α = .86 for boys], appearance comparisons [α = .88 for girls, α = .82 for boys] and appearance conversations [α = .90 for girls, α = .86 for boys].

Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction with Body Parts Scale (Stice 2001)

Total body dissatisfaction scores were calculated by summing ratings of personal dissatisfaction with nine body parts (see Appendix) between 1 = extremely satisfied and 5 = extremely dissatisfied. This scale is reliable, stable, and valid in Western samples (e.g., Bearman et al. 2006). PCA resulted in univariate structures comprised of all items for each gender in this sample. For girls, the solution accounted for 57.09% of the scale variance (KMO = .90, p < .001). Among boys, 61.39% of the scale variance was explained by the solution (KMO = .92, p < .001). Alphas were high for girls (α = .90) and boys (α = .92).

Results and Discussion

Preliminary Analyses

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics and univariate F values for gender and age group on measures. Once again, mean BMI levels were lower than those reported in comparable American samples (e.g., Bearman et al. 2006; Jones 2004) while average material SES levels were higher than those reported by Shi et al. (2006). Public self-consciousness averages all exceeded the mid-point between “Occasional” and “Some”. Girls, particularly middle adolescent girls, had at least “Occasional” mean appearance pressure, comparison and conversations scores while boys endorsed less than “Occasional” appearance pressure and conversation levels and at least “Occasional” peer appearance comparisons. Boys reported “Moderately Low” body dissatisfaction on average while early and middle adolescent girls scored within “Moderately Low” and “Neutral” ranges of average body dissatisfaction, respectively. Notably, few boys (6.4%) or girls (16.6%) reported moderately high or very high body dissatisfaction levels compared to rates for American boys (16%) and girls (36%) of the same approximate age (Bearman et al. 2006).

Regarding group differences, younger students reported a higher material SES, a lower BMI and less public self-consciousness than did older students (Table 2). Girls reported more public self-consciousness and a lower BMI than did boys but none of the gender × age interactions on demographics was significant (see Table 2).

Main Analyses

To test for gender differences in appearance pressure, comparisons, conversations, and body dissatisfaction as well as gender × age group effects reflecting elevations for middle adolescent girls compared to other groups, a 2 (Gender) × 2 (Age Group) MANCOVA was conducted. Multivariate effects emerged for Gender, F (5, 1388) = 48.89, p < .001, Age, F (5, 1388) = 19.13, p < .001, and their interaction, F (5, 1388) = 9.13, p < .001, independent of material SES, F (5, 1388) = 2.72, p < .02, BMI, F (5, 1388) = 47.54, p < .001, and public self-consciousness, F (5, 1388) = 210.06, p < .001.

Girls reported elevations on all dependent measures compared to boys (Table 2). In contrast to Study 1, univariate effects for age were significant, with older students scoring higher on all measures. Partial support was obtained for hypothesized gender × age group interactions. Older girls reported more pressure from mass media (p < .002), comparisons with peers (p < .001) and conversations with friends (p < .001) than did younger girls but the interaction for interpersonal pressure was not significant. No age differences on media and interpersonal scales were found for boys [all p-values < .08] (see Table 2). Body dissatisfaction levels were higher for middle adolescent girls than younger girls (p < .001), younger boys (p < .001) or middle adolescent boys (p < .001). Early adolescent girls were more dissatisfied than were early (p < .001) or middle (p < .001) adolescent boys. Less expectedly, middle adolescent boys had more body dissatisfaction than younger boys did (p < .001).

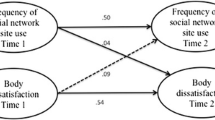

Mediating effects of media and interpersonal influences on gender, age group and gender × age differences in body dissatisfaction were assessed via correlation and hierarchical multiple regression analyses. Following Darlington (1990), mediation would be demonstrated if (1) gender, age group, and gender × age group had significant associations with media and interpersonal factors (2) in turn, these media and interpersonal factors had significant relations with body dissatisfaction and (3) effects of gender, age group, and gender × age group were attenuated in the prediction of body dissatisfaction after controlling for media and interpersonal correlates of body dissatisfaction.

Table 2 indicates gender and age group were related to each media or interpersonal factor and body dissatisfaction. However, due to the requirement that categorical measures be dichotomous in correlation and linear regression analyses, gender × age group interaction terms in between groups analyses were transformed into a centered dichotomous gender × age group contrast (i.e., middle adolescent girls versus all other subgroups) based on recommendations of Stockburger (2001). Partial correlation analyses controlling for group differences in BMI, public self-consciousness, and material SES indicated this gender × age group contrast was related to appearance-based pressure from mass media, r = .19, p < .001, and close relationships, r = .07, p < .008, appearance comparisons, r = .17, p < .001, appearance conversations, r = .24, p < .001, and body dissatisfaction, r = .29, p < .001, but was not multicollinear with gender, r = .50, p < .001, or age group, r = .57, p < .001. Each association for the gender × age group contrast reflected elevations among middle adolescent girls compared to other adolescents. In sum, these analyses linked gender and the gender × age group contrast with each media and interpersonal appearance influence.

Within each gender, significant bivariate correlations were found between body dissatisfaction and BMI but not public self-consciousness or not material SES (Table 3). Subsequent partial correlation analyses indicated that all media and interpersonal factors were related to body dissatisfaction, independent of BMI (Table 3).

With the exception of material SES and public self-consciousness which were not related to body dissatisfaction, the other measures were included in hierarchical regression analyses to evaluate mediating effects of media and interpersonal factors on gender and the gender × age group contrast on body dissatisfaction. In initial regression runs, appearance conversations had significant negative standardized beta values in contrast to its positive associations with body dissatisfaction in partial correlation analyses. This pattern reflected modest but significant suppression of error variance, so analyses were re-run dropping appearance conversations from prediction equations. No evidence of multicollinearity among predictors was observed in the final regression equations as reflected by the finding that all variance inflation factor values were lower than 3.25.

Table 4 presents findings from regression equations that assessed effects of two different sequences of predictors on body dissatisfaction. Overall, Adjusted R 2 = .292 of body dissatisfaction scores was explained by each model, F (7, 1391) = 83.34 p < .001. In the initial model, gender and age group (Block 2) and the gender × age group contrast (Block 3) contributed to body dissatisfaction, independent of BMI (Block 1). After controlling for these factors, pressure from media and interpersonal sources (Block 4) added unique variance to the model. In an alternate model designed to assess mediation (Table 4), variance in body dissatisfaction explained by gender and age group (Block 3) was reduced to R 2 Change = .082 from R 2 Change = .115 in the initial model, after controlling for media/interpersonal factors (Block 2). These results indicated the impact of gender, in particular, on body dissatisfaction was partially mediated by reported appearance pressure. Furthermore, the gender × age contrast (Block 4) was no longer significant in the alternate model, indicating its impact on body dissatisfaction was fully mediated by media and interpersonal influences.

In sum, adolescent girls were more dissatisfied with their bodies and endorsed more appearance pressure, comparisons, and conversations than did either younger girls or boys. Compared to Study 1, effects of age group were more pronounced—older students reported more body dissatisfaction and elevations on all interpersonal and media scales than did younger students. These main effects were qualified by interactions indicating 15–17 year old girls were more highly dissatisfied with their bodies and more immersed in appearance-based interpersonal and media experiences than 11–13 year old girls were. Middle adolescent boys also acknowledged more body dissatisfaction than did early adolescent boys, despite no corresponding age differences on media and interpersonal measures.

Past work has implicated appearance pressure in the prediction of varied body image concerns of adolescent Chinese girls and boys (e.g., Chen et al. 2007; Jackson and Chen 2008a, b; Xu et al. 2010) but this study indicated perceived pressure from mass media, friends, and family could fully account for the higher overall body dissatisfaction level of middle adolescent girls compared to other groups. That said, mediating effects of mass media and interpersonal factors on the gender difference in body dissatisfaction were modest and should not be overstated in explaining body dissatisfaction differences between the girls and boys.

General Discussion

Gender Differences in Interpersonal and Media Correlates of Body Dissatisfaction

Sociocultural models have implicated body mass as well as appearance-based pressure, comparisons, attractiveness ideals and conversations as potential influences on body dissatisfaction (Jones 2004; Thompson et al. 1999). While much of the past literature is based on within-gender effects and adolescents in the U.S. (Ata et al. 2007; Jones 2004), Europe (e.g., Knauss et al. 2008; Rodgers et al. 2009) or Australia (e.g., Humphreys and Paxton 2004; Vincent and McCabe 2000), this research illustrated unambiguous gender differences in susceptibility to general appearance pressure from mass media and close social ties, appearance comparisons with peers, and physical attractiveness as a focus of discussion with close friends in two samples of urban Chinese adolescents. Relative elevations among girls are in line with the contention that physical attractiveness and appearance ideals are more central to the identity of Chinese females (Jung et al. 2010) than Chinese males. As such, pressure, self-evaluations, and conversations of early and middle adolescent girls seem to center on physical appearance more strongly than they do for boys of the same ages.

Each gender × age group interaction was significant in at least one sample and indicated middle adolescent girls were more prone than younger girls to interpersonal and media influences on body dissatisfaction; the most pronounced effects were found for mass media pressure and appearance conversations with friends. In contrast, there was little variation in endorsements of media and interpersonal influences between older and younger boys. Some authors have argued girls become more aware of attractiveness ideals as they proceed through adolescence while the body becomes less important for males, particularly when pubertal changes bring boys’ bodies in line with mesomorphic ideals (e.g., McCabe and Ricciardelli 2005). This research suggested that, independent of normative changes in body mass or public self-consciousness, physical appearance is a prominent focus in the social environments of middle adolescent Chinese girls compared to younger girls or boys. The rising import of physical appearance in peer interactions (e.g., Jones et al. 2004) and pressure to emulate media ideals of attractiveness (Knauss et al. 2008; Shroff and Thompson 2006) may correspond to middle adolescent Chinese girls’ increased vulnerability to body dissatisfaction.

Group Differences in Body Dissatisfaction

Indeed, Chinese girls reported more body dissatisfaction than Chinese boys and middle adolescent girls had higher levels than any other group. While gender differences in body dissatisfaction have been widely documented across cultures (e.g., Ata et al. 2007; Chen and Jackson 2008; Knauss et al. 2008), they are not trivial. Body dissatisfaction is among the strongest risk factors for clinical eating disorders (Jacobi et al. 2004; Stice and Shaw 2002), syndromes that carry substantial risks for disability (Berkman et al. 2007) and premature mortality (Streigel-Moore and Bulik 2007), especially for girls and young women. As such, efforts to identify reliable predictors of body dissatisfaction and vulnerable subgroups are not easily dismissed.

Less expectedly, middle adolescent boys in Study 2 reported more body dissatisfaction than did younger boys even though no corresponding differences were observed on interpersonal and media correlates of body dissatisfaction. Because introspection, time spent alone, and autonomy strivings can increase for boys over the course of adolescence (e.g., Steinberg 2007), the potency of intra-personal influences on body dissatisfaction might predominate over “contextual” factors for boys during middle adolescence. This conjecture requires further evaluation but studies of boys from the U.S. (Paxton et al. 2006) and China (Jackson and Chen 2011) have found measures of negative affect contribute prospectively to body dissatisfaction or eating disturbances during middle or late adolescence while interpersonal factors (e.g., appearance pressure, teasing, or conversations with peers) have comparably stronger effects during early adolescence.

Predictors of Body Dissatisfaction

Aside from gender and age, BMI and interpersonal/media influences emerged as predictors of body dissatisfaction in Study 2. Consistent with research on Chinese adolescents of each gender (Chen et al. 2007; Jackson and Chen 2008a, b; Xie et al. 2006), adolescents who had a higher BMI were also more likely to report overall dissatisfaction with their bodies. Given that overweight and obesity are not yet common in this segment of the population (Popkin 2010), adolescent girls and boys whose BMI deviates too far from local BMI norms may feel stigmatized and less satisfied with their overall appearance. Beyond the impact of demographics and developmental factors, heightened pressure from mass media and from family and friends contributed to elevations in body dissatisfaction. When considered with conclusions about features of effective prevention programs (e.g., Stice et al. 2007), these findings suggest interventions that increase awareness and reduce negative effects of media and interpersonal messages promoting unrealistic appearance ideals as well as lifestyle programs targeting exercise and healthful diets have utility in reducing body dissatisfaction for Chinese adolescents in general. Because appearance pressure measures fully mediated the gender × age group contrast in body dissatisfaction, interventions are likely best employed in early adolescence before interpersonal and media factors become entrenched and body dissatisfaction intensifies, especially for middle adolescent girls.

Comparisons to Adolescents from Western Countries

Finally, the main research focus was upon elucidating body dissatisfaction and its correlates in subgroups of Chinese adolescents yet select comparisons are possible with Western research samples of the same approximate age, given the same measures. Regarding cross-cultural differences, groups in this research were far less likely than their American counterparts of the same age (Bearman et al. 2006) to score very high or moderately high on body dissatisfaction. In part, this difference may reflect possible cultural differences in correlates of body dissatisfaction.

Most obviously, although obesity rates have increased dramatically among young Chinese children (e.g., Popkin 2010), average BMI levels in our respondents were lower than those of American samples similar in age (Bearman et al. 2006; Jones 2004). Furthermore, girls were less likely to make appearance comparisons with peers or engage in appearance conversations with friends than American girls, respectively in Shroff and Thompson’s (2006) sample and Jones’ (2004) samples. Although comparisons on interpersonal pressure were not possible, average media pressure scores of our groups seemed comparable to those reported among Swiss 14–16 year old girls and boys completing a slightly different constellation of SATAQ-3 “pressures” items (Knauss et al. 2008). Finally, Chinese boys reported more appearance conversations with friends than boys in Jones (2004) sample. Together, these findings suggest that select developmental and interpersonal influences on body dissatisfaction may be less prominent among adolescent girls in China than peers in the U.S. However, culture group differences were not uniform across measures and replications are needed in studies specifically designed to explore cross-cultural similarities and differences.

Limitations, Future Research, Conclusions

Notwithstanding its implications, the main limitations of this research must be noted with future research directions. First, to build upon the snapshot of gender and age group differences provided here, prospective studies that track body dissatisfaction and its correlates over time are needed. Second, because urban, predominantly Han adolescents were assessed, consideration of other age groups, ethnic minorities, and samples from other countries might elucidate the salience of interpersonal and media influence on body dissatisfaction across the lifespan and within specific subcultures or cultures. Third, because body dissatisfaction is a robust risk factor for disordered eating (e.g., Stice and Shaw 2002) and general appearance dissatisfaction may be more intense than concerns specific to height, facial features, fatness, thinness, or muscularity in Chinese samples (Chen et al. 2006; Jung et al. 2010), continued research on body dissatisfaction in China is warranted.. However, gender and age differences in overall body dissatisfaction do not necessarily apply to specific appearance concerns as highlighted by Xu et al.’s (2010) findings on muscle-building efforts of Chinese boys. Hence, research on overall body dissatisfaction should be complemented by studies on focused appearance concerns, particularly of Chinese males.

Fourth, while back-translation, PCA, and intercorrelations among measures supported the validity of scales used, scale validation is an ongoing process; further assessment of instruments is warranted in Chinese samples, especially for multidimensional measures. To illustrate, while we used only the SATAQ-3 “Pressure” subscale, recent evaluations of the full SATAQ-3 indicated “Pressure” and “Internalization” items load together on a single factor in Malaysian (Swami 2009) and Chinese samples (Jackson and Chen 2010b). Evidence highlighting how exposure to Asian (rather than Western) media is more strongly related to weight concerns of Chinese girls (Xie et al. 2006), thinness as a feminine ideal in China long before contact with Western cultures increased, and the lower appeal of muscularity as a masculine appearance ideal for many males of Chinese descent (Jung et al. 2010; Yang et al. 2005) all suggest scales that tap “Western” versus local media influence are needed to evaluate the commonly-voiced yet largely untested assumption that exposure to Western media drives body image concerns in Asian countries such as China.

Finally, the scope of possible influences on body dissatisfaction should be expanded in future work. Aside from negative affect, processes of objectification and internalization of culturally-sanctioned attractiveness ideals can be added to protocols. Further, as reflected by the long hours many students devote to regular academic curriculum and after-school programs with classmates, Chinese schools assume strong social functions while fulfilling students’ needs for studying (Stevenson and Zusho 2002). Hence, facets of school culture including social support and status with one’s peers deserve attention. Behavioral and observer indices of contact with media and social networks can help to clarify linkages between social environs of adolescents, perceptions of such environments, and appraisals of one’s physical appearance.

These considerations aside, this research may be the first to emphasize middle adolescent Chinese girls’ susceptibility to body dissatisfaction and associated mass media and interpersonal influences relative to early adolescent girls or boys in these age groups. By and large, patterns of difference were replicated across two samples, independent of age-related changes in developmental correlates of body dissatisfaction, i.e., BMI, public self-consciousness. While media and interpersonal factors did not explain the overall gender difference in body dissatisfaction, middle adolescent girls’ increased susceptibility to body dissatisfaction compared to peers was fully mediated by group differences in appearance pressure from mass media and interpersonal sources. As such, efforts should be made to reduce appearance pressure in both the social and phenomenal environments of vulnerable adolescents.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: Text-revised (4th ed.). Washington: Author.

Ata, R., Ludden, A. B., & Lally, M. (2007). The effects of gender and family, friend, and media influences on eating behaviors and body image during adolescence. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 36, 1024–1037. doi:10.1007/s10964-006-9159-x.

Barlett, C., Vowels, C., & Saucier, D. (2008). Meta-analyses of the effects of media images on men’s body-image concerns. Journal of Social & Clinical Psychology, 27, 279–310. doi:10.1521/jscp.2008.27.3.279.

Bearman, S., Presnell, K., Martinez, E., & Stice, E. (2006). The skinny on body dissatisfaction: A longitudinal study of adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 229–241. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-9010-9.

Berkman, N., Lohr, K. N., & Bulik, C. M. (2007). Outcomes of eating disorders: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40, 293–309. doi:10.1002/eat.20369.

Chen, H., & Jackson, T. (2008). Prevalence and sociodemographic correlates of eating disorder endorsements among adolescents and young adults from China. European Eating Disorders Review, 16, 375–385. doi:10.1002/erv.837.

Chen, H., & Jackson, T. (2009). Predictors of changes in weight esteem among mainland Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal analysis. Developmental Psychology, 45, 1618–1629. doi:10.1037/a001682013996281837.

Chen, H., Jackson, T., & Huang, X. (2006). Initial development and validation of the Negative Physical Self Scale among Chinese adolescents and young adults. Body Image, 3, 401–412. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2006.07.005.

Chen, H., Gao, X., & Jackson, T. (2007). Predictive models for understanding body dissatisfaction among young males and females in China. Behaviour Research & Therapy, 45, 1345–1356. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2006.09.015.

Darlington, R. B. (1990). Regression and linear models. London: McGraw-Hill. doi:10.1177/1094428104266017.

Fenigstein, A., Scheier, M. F., & Buss, A. H. (1975). Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 43, 522–527. doi:10.1037/h0076760.

Field, A. E., Camargo, C. A., Taylor, C. B., Berkey, C. S., Roberts, S. B., & Colditz, G. A. (2001). Peer, parent, and media influences on the development of weight concerns and frequent dieting among preadolescent and adolescent girls and boys. Pediatrics, 107, 54–60.

Fouts, G. T., & Burggraf, K. K. (2000). Television situation comedies: Female weight, male negative comments, and audience reactions. Sex Roles, 42, 925–932. doi:10.1023/A:1007054618340.

Fouts, G., & Vaughan, K. (2002). Television situation comedies: Male weight, negative references, and audience reactions. Sex Roles, 46, 439–442. doi:10.1023/A:1020469715532.

Frankenberger, K. D. (2000). Adolescent egocentrism: A comparison among adolescents and adults. Journal of Adolescence, 23, 343–354. doi:10.1006/jado.2000.0319.

Grabe, S., Ward, M. L., & Hyde, J. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134, 460–476. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460.

Hargreaves, D., & Tiggemann, M. (2004). Idealized media images and adolescent body image: “Comparing” boys and girls. Body Image, 1, 351–361. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.10.002.

Humphreys, P., & Paxton, S. J. (2004). Impact of exposure to idealized male images on adolescent boys’ body image. Body Image, 1, 253–266. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2004.05.001.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2007). Identifying the eating disorder symptomatic in China: The role of sociocultural factors and culturally-defined appearance concerns. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 62, 241–249. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.09.010.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2008a). Sociocultural influences on body image concerns of adolescent girls and young women from China. Sex Roles, 58, 402–411. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9342-x.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2008b). Sociocultural influences on body image concerns of young Chinese males. Journal of Adolescent Research, 23, 154–171. doi:10.1177/0743558407310729.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2008c). Predicting changes in eating disorder symptoms among Chinese adolescents: A nine month prospective study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 64, 87–95. doi:10.1016/j.psychores.2007.08.015.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2008d). Changes in eating disorder symptoms among adolescent girls and boys in China: An 18 month prospective study. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 37, 874–885. doi:10.1080/15374410802359841.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2010a). Sociocultural experiences of bulimic and non-bulimic adolescents in a school-based sample from China. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 69–76. doi:10.1007/s10802-009-9350-0.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2010b). Factor structure of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Scale-3 (SATAQ-3) among adolescent boys in China. Body Image, 7, 349–355. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.07.003.

Jackson, T., & Chen, H. (2011). Risk factors for disordered eating during early and middle adolescence: Prospective evidence from mainland Chinese boys and girls. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 45. doi:10.1037/a0022122.

Jacobi, C., Hayward, C., de Zwaan, M., Kraemer, H. C., & Argas, W. S. (2004). Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 19–65. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.130.1.19.

Jones, D. C. (2001). Social comparison and body image: Attractiveness comparison to models and peers among adolescent girls and boys. Sex Roles, 45, 645-664. doi:10.1023/A:1014815725852.

Jones, D. C. (2004). Body image among adolescent girls and boys: A longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 40, 823–835. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.823.

Jones, D., & Crawford, J. (2006). The peer appearance culture during adolescence: Gender and body mass variations. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 257–269. doi:10.1007/s10964-005-9006-5.

Jones, D. C., Vigfusdottir, T. H., & Lee, Y. (2004). Body image and the appearance culture among adolescent girls and boys. Journal of Adolescent Research, 19, 323–339. doi:10.1177/0743558403258847.

Jung, J., & Lee, S. (2006). Cross-cultural comparisons of appearance self-schema, body image, self-esteem, and dieting behavior between Korean and U.S. women. Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal, 34, 350–365. doi:10.1177/1077727X06286419.

Jung, J., Forbes, G. B., & Lee, Y. (2009). Body dissatisfaction and disordered eating among early adolescents from Korea and the US. Sex Roles, 61, 42–54. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9609-5.

Jung, J., Forbes, G., & Chan, P. (2010). Global body and muscle satisfaction among college men in the United States and Hong Kong-China. Sex Roles, 63, 104–117. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9760-z.

Knauss, C., Paxton, S. J., & Alsaker, F. D. (2008). Body dissatisfaction in adolescent boys and girls: Objectified body consciousness, internalization of the media body ideal and perceived pressure from media. Sex Roles, 59, 633–643. doi:10.1007/s11199-008-9474-7. 4, 353–360.

Lawler, M., & Nixon, E. (2011). Body dissatisfaction among adolescent boys and girls: The effects of body mass, peer appearance culture and internalization of appearance ideals. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 40, 59–71. doi:10.1007/s10964-009-9500-2.

Leung, F., Lam, S., & Sze, S. (2001). Cultural expectations of thinness in Chinese women. Eating Disorders, 9, 339–350. doi:10.1080/106402601753454903.

Li, Y. P., Hu, X. Q., Ma, W. J., Wu, J., & Ma, G. (2005). Body image perception among Chinese children and adolescents. Body Image, 2, 91–103. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2005.04.001.

McCabe, M. P., & Ricciardelli, L. A. (2005). A prospective study of pressures from parents, peers, and the media on extreme weight change behaviors among adolescent boys and girls. Behavior Research & Therapy, 43, 653–668. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2004.05.004.

McCabe, M. P., & Ricciaredelli, L. A. (2004). Body image dissatisfaction among males across the lifespan: A review of past literature. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 675–685. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(03)00129-6

McKinley, N. M. (1999). Women and objectified body conscientiousness: Mother’s and daughters’ body experience in cultural, developmental, and familial context. Developmental Psychology, 35, 760–769. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.3.760.

Nasby, W. (1989). Private and public self-consciousness and articulation of the self-schema. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 56, 117–123. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.56.1.117.

Nelson, E. E., Leibenluft, E., McClure, E. B., & Pine, D. (2005). The social re-orientation of adolescence: A neuroscience perspective on the process and its relation to psychopathology. Psychological Medicine, 35, 163–174. doi:10.1017/S0033291704003915.

Paxton, S., Eisenberg, M., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2006). Prospective predictors of body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls and boys: A five-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 42, 888–899. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.888.

Popkin, B. M. (2010). Recent dynamics suggest selected countries catching up to US obesity. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 91, 284s–288s. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2009.28473C.

Presnell, K., Bearman, S., & Stice, E. (2004). Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent boys and girls: A prospective study. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 36, 389–401. doi:10.1002/eat.20045.

Rodgers, R. F., Faure, K., & Chabrol, H. (2009). Gender differences in parental influences on adolescent body dissatisfaction and disordered eating. Sex Roles, 61, 837–849. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9690-9.

Rosenblum, G. D., & Lewis, M. (1999). The relations among body image, physical attractiveness, and body mass in adolescence. Child Development, 70, 50–64. doi:10.1111/1467-8624.00005.

Schutz, H., Paxton, S. J., & Wertheim, E. (2002). Investigation of body comparison among adolescent girls. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 32, 1906–1937. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2002.tb00264.x.

Shi, Z., Lien, N., Nirmal Kumar, B., & Holmboe-Ottesen, G. (2006). Physical activity and associated socio-demographic factors among school adolescents in Jiangsu Province, China. Preventive Medicine, 43, 218–221. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.04.017.

Shroff, H., & Thompson, J. K. (2006). Peer influences, body-image dissatisfaction, eating dysfunction and self-esteem in adolescent girls. Journal of Health Psychology, 11, 533–551. doi:10.1177/1359105306065015.

Smart, A. (1999). Expressions of interest: Friendship and guanxi in Chinese societies. In S. Bell & S. Coleman (Eds.), The anthropology of friendship (pp. 119–136). New York: Berg.

Steinberg, L. (2007). Adolescence. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Stevenson, S. W., & Zusho, A. (2002). Adolescence in China and Japan. In B. B. Brown, R. W. Larson, & T. S. Saraswath (Eds.), The world’s youth (pp. 141–170). London: Cambridge University.

Stice, E. (2001). A prospective test of the dual pathway model of bulimic pathology: Mediating effects of dieting and negative affect. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 110, 124–133. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.110.1.124.

Stice, E., & Agras, W. S. (1998). Predicting onset and cessation of bulimic behaviors during adolescence: A longitudinal grouping analysis. Behavior Therapy, 29, 257–276. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(98)80006-3.

Stice, E., & Shaw, H. (2002). Role of body dissatisfaction in the onset and maintenance of eating pathology: A synthesis of research findings. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53, 985–993. doi:10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00488-9.

Stice, E., Shaw, H., & Marti, C. N. (2007). A meta-analytic review of eating disorder prevention programs: Encouraging findings. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 207–231. doi:10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091447.

Stockburger, D. W. (2001). Multivariate statistics: Concepts. models, and applications. Springfield: Missouri State University.

Striegel-Moore, R. H., & Bulik, C. M. (2007). Risk factors for eating disorders. American Psychologist, 62, 181–198. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.62.3.181.

Striegel-Moore, R. H., Silberstein, L. R., & Rodin, J. (1993). The social self in bulimia nervosa: Public self-consciousness, social anxiety, and perceived fraudulence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 297–303. doi:10.1037/0021-843X.102.2.297.

Swami, V. (2009). An examination of the factor structure of the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 in Malaysia. Body Image, 6, 129–132. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.01.003.

Thompson, J. K., Heinberg, L. J., Altabe, M., & Tantleff-Dunn, S. (1999). Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. Washington: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/10312-000.

Thompson, J. K., van den Berg, P., Roehrig, M., Guarda, A., & Heinberg, L. J. (2004). The Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-3 (SATAQ-3): Development and validation. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 35, 293–304. doi:10.1002/eat.10257.

Vincent, M., & McCabe, M. (2000). Gender differences among adolescents in family, and peer influences on body dissatisfaction, weight loss, and binge eating behaviors. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 29, 205–221. doi:10.1023/A:10051566161732000.

Warren, C., Schoen, A., & Shafer, K. (2010). Media internalization and social comparison as predictors of eating pathology among Latino adolescents: The moderating effect of gender and generational status. Sex Roles, 63, 712–724. doi:10.1007/s11199-010-9876-1.

Wertheim, E. H., Paxton, S. J., & Blaney, S. (2009). Body image in girls. In L. Smolak & J. K. Thompson (Eds.), Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth (pp. 47–76). Washington: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/11860-003.

Wildes, J. E., & Emery, R. E. (2001). The roles of ethnicity and culture in the development of eating disturbance and body dissatisfaction: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 21, 521–551. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00071-9.

Xie, B., Chou, C. P., Spruijt-Metz, D., Reynolds, K., Clark, F., Palmer, P., et al. (2006). Weight perception and weight-related sociocultural and behavioral factors in Chinese adolescents. Preventive Medicine, 42, 229–234. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.12.013.

Xu, X., Mellor, D., Kiehne, M., McCabe, M., Ricciardelli, M., & Xu, Y. (2010). Body dissatisfaction, engagement in body change behaviors and sociocultural influences on body image among Chinese adolescents. Body Image, 7, 156–164. doi:2010-01625-00110.1016/j.bodyim.2009.11.003.

Yang, C., Gray, P., & Pope, H. G. (2005). Male body image in Taiwan versus the West: Yanggang Zhiqi meets the Adonis complex. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162,263–269. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.263.

Acknowledgement

This research was supported by grants from the Foundation program for Humanities and Social Science research, State Education Commission (08JAXLX014), The Key Discipline Fund of National 211 Project, China (NSKD08004), and the School of Arts and Social Sciences, James Cook University. Select findings from Study 2 were presented in a poster at the 2009 convention of the American Psychological Association. We thank Zhang Tingyan, Rao Ying, He Yulan, Gao Xiao, Liang Yi, Jiang Xiaxia, Chen Minyan, Pan Chenjing, Liukun, Yang Tingting, and Zhao Yi for assistance with data collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix: Research Measures (附录:测量工具)

Appendix: Research Measures (附录:测量工具)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, H., Jackson, T. Gender and Age Group Differences in Mass Media and Interpersonal Influences on Body Dissatisfaction Among Chinese Adolescents. Sex Roles 66, 3–20 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0056-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0056-8