Abstract

Gender-based structural power and heterosexual dependency produce ambivalent gender ideologies, with hostility and benevolence separately shaping close-relationship ideals. The relative importance of romanticized benevolent versus more overtly power-based hostile sexism, however, may be culturally dependent. Testing this, northeast US (N = 311) and central Chinese (N = 290) undergraduates rated prescriptions and proscriptions (ideals) for partners and completed Ambivalent Sexism and Ambivalence toward Men Inventories (ideologies). Multiple regressions analyses conducted on group-specific relationship ideals revealed that benevolent ideologies predicted partner ideals, in both countries, especially for US culture’s romance-oriented relationships. Hostile attitudes predicted men’s ideals, both American and Chinese, suggesting both societies’ dominant-partner advantage.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

On the surface, sexism and close relationships do not intersect. Common sense dictates that successful heterosexual relationships are suffused with love and caring, not sexism. The current research confronts this assumption by exploring how sexism not only affects close relationships, but is integral to venerated and subjectively positive cultural ideals about the perfect mate. In common with other sexism theories, ambivalent sexism theory (AST; Glick and Fiske 1996, 1997, 1999) posits that women often face overt and unfriendly prejudices (such as hostility toward women who occupy nontraditional roles), but also that men face reflected hostility, the resentment directed toward those with greater power. Hostile attitudes represent blatant and antagonistic attempts at influencing who male and female partners are “supposed to be.” In addition, however, ambivalent sexism posits that heterosexual interdependence creates subjectively benevolent, but still sexist, justifications for gender inequality. These benevolent attitudes, which idealize women as nurturing subordinates and men as assertive providers, represent the “soft power” people use to control their partner. AST suggests that hostility and benevolence work together, reinforcing gender inequality, even in people’s most personal relationships. This study uniquely examines sexism for both genders’ relationship ideals in the same study.

AST suggests that benevolent gender attitudes exert insidious influences where people least suspect, namely, in close relationships, affecting both men’s and women’s partner ideals due to heterosexuals’ mutual interdependence. In contrast, hostile ideologies, more nakedly linked to power, may exert more of a one-way influence in close relationships by shaping the culturally more powerful (male) partner’s requirements for the “ideal” (female) mate. The present research also investigated how these dynamics between gender ideologies and relationship ideals manifest in two cultures, one characterized by beliefs in romance, and the other characterized by (more overt) gender inequality.

Ambivalent Sexism

Ambivalent sexism has its roots in patriarchal, social structural control. This power imbalance—men hold superior status but also provider responsibilities—together with (a) gender-role differentiation along stereotypic traits and division of labor as well as (b) partners’ genuine desire for intimacy, creates a unique combination that breeds ambivalent (yet highly correlated) hostile and benevolent gender ideologies. The ambivalent combination of hostility and benevolence targets both genders. Further, these hostile and benevolent ideologies each encompass three elements of male-female relations: power, gender roles, and heterosexuality.

The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (ASI: Glick and Fiske 1996, 1997) assesses hostile (HS) and benevolent (BS) attitudes toward women. HS endorses dominative paternalism, competitive gender-role differentiation, and combative heterosexuality, whereas BS endorses protective paternalism, complementary gender-role differentiation, and romanticized heterosexuality. HS aims to punish women who challenge male dominance, while BS reinforces that dominance by assigning women positive but low-status, communal traits (e.g., pure, caring), which align with restrictive, subordinate roles (e.g., homemaker).

The Ambivalence toward Men Inventory (AMI: Glick and Fiske 1999) assesses hostile (HM) and benevolent (BM) attitudes toward men. HM entails resentment of paternalism, of men’s higher status in society, and of male aggressiveness; although HM thereby depicts men less positively than women, it reinforces viewing men as possessing traits associated with status and societal dominance. BM, on the other hand, expresses attitudes opposite in valence: It acknowledges and admires men’s higher status and accepts complementary gender roles (e.g., protector), but at the same time views men as deficient in roles typically assumed by women (e.g., as helpless domestically).

AST broadens previous understandings of sexism by considering the context of close relationships, making two major theoretical contributions to other conceptions of sexism. First, men also are targets of sexism. Second, sexism involves subjectively positive, benevolent ideologies. In short, both men and women face hostile and benevolent attitudes. AST further predicts that hostility and benevolence operate differently in close relationships, depending on two major contextual factors: (a) gender power differentials between partners, as hostility is rooted in struggles between male dominance and female resistance, and (b) cultural notions of the degree to which relationships are founded on romance as compared to pragmatic considerations.

Hostility is the Blatantly Powerful Way to Influence the Relationship

Hostile gender ideologies stem from a combative view of gender relations in society: characterizing men as aggressive and dominant, women as attempting to turn the tables by controlling men. Accordingly, people’s hostile gender attitudes correlate with other variables that relate to concerns with intergroup competition and status, for example, social dominance orientation and the Protestant work ethic (American adults; Christopher and Mull 2006). In common, hostile sexist attitudes toward each gender openly express a power struggle between the sexes. Although correlates of hostility toward men have not yet been systematically studied, hostility toward women predicts negative evaluations of women who threaten male power. Some concrete examples include giving negative recommendations for female candidates and positive recommendations for male candidates in management (British students and adults; Masser and Abrams 2004), as well as negative evaluations of career women (American undergraduates; Glick et al. 1997).

The power differential between women and men at the societal level can, and does, seep into their private lives. The group-level struggle for power and status reflected in sexist ideologies filters down into personal relationships between individuals. For example, in Turkey and Brazil, where women occupy a much lower status than men, hostility toward women predicts people’s approval of husbands using physical violence to control their wives (Turkish and Brazilian students and adults; Glick et al. 2002). Other studies suggest similarly that sexist hostility upholds male power within heterosexual relationships: Hostile ideologies toward women predict men’s willingness to coerce sex (British students; Abrams et al. 2003), and, together with authoritarian and rape-myth beliefs, HS also predicts men’s self-reports of sexually harassing women (American undergraduates; Begany and Milburn 2002).

Because hostility is about competition for status and power, men—by many measures (e.g., higher income, higher status positions), the societal dominant group (United Nations Development Programme 2005)—have an added advantage of exercising control through hostility in relationships. People with high status are generally freer to exercise hostility, whereas low status individuals are typically prohibited from doing so. Anger, for example, is a hostile emotion expected of high- but not low-power people (American students and adults; Tiedens 2001). Women, on the other hand, must be nice and warm (and never hostile) (American undergraduates; Prentice and Carranza 2002), and women receive backlash when they violate this prescription (American undergraduates; Rudman and Glick 2001), consequently learning to comply with the warmth prescription. These observations about hostile sexism lead to our first prediction (H1) that men’s hostile sexist ideologies will guide their close relationship ideals. As the high status group member, the male partner is freer to rely on hostile attitudes to create demands for what he expects from his partner and set boundaries for what he is willing to allow in that partner.

Benevolence is the Romantic Way to Influence the Relationship

Compared to hostility, benevolent attitudes offer a less blatant approach for members of either sex to maintain gender inequality by prescribing traditional gender roles for people. For women, that implies a subordinate role. On the national level, endorsement of benevolent sexism is related to United Nations indicators of gender inequality, such as the participation of women in the economy and in politics (Glick et al. 2000; Glick and Fiske 2001). On the individual level, gender ideologies can promote or undermine the motivational goals that underlie people’s value priorities (Feather 2004). In particular, benevolence toward women and men relate to two major value types (derived from Schwartz 1992). Benevolent sexism negatively relates to self-direction values—concerns with independent thought and action, freedom, and choosing one’s own goals—and positively relates to tradition values, or concerns with respecting, accepting, and committing to one’s cultural or religious customs and ideas (Australian undergraduates; Feather 2004). System-justification research provides another link between benevolence and desire to maintain the status quo: Women primed with benevolently sexist attitudes toward women judged society as more fair (American undergraduates; Jost and Kay 2005).

Benevolently sexist gender ideologies stem from intimate interdependence between men and women; not coincidentally, these ideologies suffuse traditional notions of “romance.” Among the traditional gender roles associated with benevolent beliefs are the paternalistically chivalrous male (British undergraduates; Viki et al. 2003) and the female caretaker (American undergraduates; Glick et al. 1997). These romantic idealizations discourage people from transcending prescribed traditional gender roles: The more a woman associates male romantic partners with chivalry, the less interest she shows in education, career goals, and earning money (American undergraduates; Rudman and Heppen 2003). Further, benevolent gender attitudes predict evaluations of women based on whether or not they fit the traditional, sexually pure, virtuous female. Traditionally positive female subtypes (e.g., chaste) elicit increased benevolence (New Zealander undergraduates; Sibley and Wilson 2004), while women who have had premarital sex receive the most negative evaluations from perceivers highest in BS (Turkish students and adults; Sakalli-Ugurlu and Glick 2003). Furthermore, acquaintance rape victims perceived as violating feminine virtue norms (e.g., by initiating kissing before they were raped) receive the most blame from those high in BS (British students; Abrams et al. 2003; British students; Viki and Abrams 2002) because they are seen as sexually impure.

The most recent, direct research on sexism and relationship partner ideals shows that benevolent ideologies predict people’s preferences for a traditional partner (for women, an older man with good earning potential, and for men, a younger woman who can cook and keep house), in nine nations (Eastwick et al. 2006). In another study, women high in BS were more likely to seek a male partner with good earning potential, while men high in BS were more interested in a chaste partner; both choices reinforce traditional romantic roles (American undergraduates; Johannesen-Schmidt and Eagly 2002). In a study conducted in parallel with the current research, benevolence predicted certain power-related marital-partner criteria, such as submission, respect, and provider status (American and Chinese undergraduates; Chen et al. 2009; our discussion returns to compare the current study with Chen et al.).

Women are more willing to accept benevolent as compared to hostile gender ideologies, which idealize their traditional role (Glick et al. 2000, 2004). Indeed, women like men who express benevolent sexism more than men who are hostile sexists, perhaps because they are less likely to construe benevolence as sexism than to recognize hostile sexism (Dutch undergraduates; Barreto and Ellemers 2005). In addition, women endorse benevolent sexism more than men in those countries where the gender disparity is greatest (Glick et al. 2000). Because benevolent attitudes are subjectively positive, at the very least for the perceiver (Glick and Fiske 1996; British students and adults; Masser and Abrams 1999), they allow people to maintain a positive viewpoint of and legitimize partners’ unequal roles in romantic relationships (e.g., “She needs to stay at home because she is a natural caretaker”) and consequently glorify partners of each gender who fulfill their traditional roles. Positive feelings, even when they act to legitimize inequality, are crucial for both the maintenance of romantic relationships (American students and adults; Stafford and Canary 1991) and are a product of those relationships or potential relationships (Brehm 1992; American undergraduates; Goodwin et al. 2002).

Based on this literature, we generated our second prediction (H2) that women’s relationship ideals will be shaped by benevolent ideologies. This prediction is based on the logic that when the subordinated group is prohibited from being hostile, benevolent ideologies offer an attractive alternate means to reinforce gender inequality, all while avoiding conflict, which is costly for both sides, but especially for those who have less power (i.e., women).

Culture: Romantic Love and Gender Disparity

Although ambivalent sexism has demonstrated strong cross-cultural validity (Glick et al. 2000, 2004), social constructions of romance are not culturally universal. People in Western cultures are more likely to prescribe romantic love as a precondition for marriage (American undergraduates; Kephart 1967; multi-national participants; Levine et al. 1995; American undergraduates; Simpson et al. 1986). Similarly, the extent to which “psychological intimacy” is an important element of marital satisfaction and personal well-being varies as a function of individualism (Canadians and Americans) and collectivism (Chinese, Indians, Japanese), with collectivists less likely to consider it important (Dion and Dion 1993). Research suggests that East Asians, for example, generally understand close relationships differently than Westerners. Japanese young adults do not endorse romantic beliefs as strongly as their American counterparts (Sprecher et al. 1994). Similarly, Chinese participants are more likely to agree with conceptions of love as deep friendship (Dion and Dion 1996). Indeed, the notion of romantic love is a recent import into the Chinese language: The word “lien ai” was specifically created to represent this concept (Hsu 1981). For more general literature on cultural influences on relationships and relationship styles in China, see Riley (1994) and Pimentel (2000).

This conception of romantic love is evident in Western media depictions, including the popular television show Sex and the City; in one episode, the central character and cultural icon Carrie Bradshaw declares, “I’m looking for love. Real love. Ridiculous, inconvenient, consuming, can’t-live-without-each-other love” (King and Van Patten 2004). The notion of romantic love as virtually sacred and magical represents a powerful cultural belief, endorsed strongly by Americans. In comparison, some Chinese samples endorse a more avoidant ideal for adult attachment (Taiwanese and American undergraduates; Wang and Mallinckrodt 2006). Perhaps the cultural difference might be best illustrated by Berscheid and Meyers’s (1996) differentiation between the uses of “love” and “in love.” While Americans fall “in love,” Chinese “love” their partners. When the social construction of love is chivalrous and romantic, benevolent attitudes ought to most effectively guide close relationships: Our third prediction (H3) is that benevolent gender ideologies will shape Americans’ relationship ideals. We base our prediction on the logic that when people subscribe to notions of romantic love, their relationship expectations should be guided by softer, nicer gender attitudes—that is, benevolent sexism—as opposed to the overtly antagonistic attitudes expressed by hostile sexism.

By contrast with American culture, the Chinese are less likely to idealize romance in heterosexual relations; for example, by viewing marriage as based on pragmatic considerations. Further, there is a greater disparity between the status of men and women in China than in the US. For example, United Nations indices such as the GDI (which assesses gender equality in longevity, education, and standard of living) and the GEM (which assesses the degree to which women have attained high status roles in business and government) indicate that Chinese women face much greater gender inequality than do American women. This reality of gender disparity leads us to our fourth prediction (H4) that Chinese partner ideals should relate to hostile ideologies. Because the hostile component of these ideologies has deep roots in intergroup competition, we expected that the role of HS would be especially strong in China, for men because of the dominance that privileges men over women, and for women, because of the male resentment it may create.

The Current Research: Relationship Ideals and Ambivalent Gender Ideologies

Scant research has investigated ambivalent sexism in close relationships. The current research extends the study of sexism by examining how exactly hostile and benevolent gender ideologies guide people’s ideals for their partner. American and Chinese college samples reported the relative importance of benevolent and hostile ideologies in cultural contexts known to differ 1) in gender inequality and 2) in their subscription to beliefs about romance. The American sample represents a culture high in egalitarian, individualistic norms that idealizes notions of close relationships as romantic love. The Chinese sample represents a culture with stronger gender gaps in societal power that traditionally places less emphasis on romance in close relationships.

Income is an important variable in dating, as it affords people to be choosier in their mate selection (Kurzban and Weeden 2005) and in the other direction, people with high (potential) income are also more desirable (Buss and Shackelford 2008). In the current research, we were interested in how much of people’s relationship ideals are influenced by cultural differences in gender disparity and understandings of love, above and beyond sheer differences in SES. Income might predict things that people more or less universally want (e.g. attractiveness) but ambivalent gender attitudes might explain other relationship requirements. To tease apart what types of relationship demands are afforded by an individual’s income, and what demands could be explained by antagonistic or softer gender ideologies, we explored the role of all three: hostile and benevolent attitudes, and income.

Assessing Close Relationship Ideals

People approach close relationships with culturally-informed beliefs about what each partner, based in part on gender, should be like, or do, in heterosexual partnerships. We measured these ideals by studying people’s prescriptions and proscriptions for relationship partners. Prescriptions are expectations that a potential partner ought to meet, including how that person should be, how she or he should behave, and the roles she or he should fulfill (Burgess and Borgida 1999). Traditional prescriptions for a woman might include being nurturing, submissive, and fulfilling the homemaker role. Prescriptions for a man might include being competent, protective, and providing for his partner. In short, prescriptions convey the shoulds. Proscriptions, the should-nots, specify what a partner should not be like or do; they communicate the boundaries one sets for a potential partner. Traditional proscriptions for a woman might be that she is not promiscuous, does not withhold affection, and does not humiliate her partner by fulfilling the breadwinner role. Traditional proscriptions for a man might emphasize that he must not be unmotivated, physically weak, or a stay-at-home partner.

Gender-specific close-relationship prescriptions and proscriptions can differ by whether they are gender-intensified or gender-relaxed. Gender-intensified norms are especially required of a partner of a specific gender, while gender-relaxed norms refer to characteristics desirable but not required of that gender (Prentice and Carranza 2002). As an example, being warm traditionally represents a gender-intensified prescription for female partners (they must be warm), while being intelligent represents a gender-relaxed prescription (an attractive trait, but not necessary for a woman to be considered a desirable partner) (American undergraduates; Prentice and Carranza 2002). The current study investigates gender-intensified prescriptions and proscriptions to examine people’s most cherished gendered ideals, not the qualities they might merely prefer but might sacrifice.

These intensified close relationship ideals, therefore, represent strong demands about how the partner must behave. Such demands differ from descriptive gender stereotypes, which merely portray beliefs about how men and women typically differ (Burgess and Borgida 1999). We believe that prescriptions and proscriptions come with much stronger affective reactions and, when applied to close relationships, function to select and then control one’s partner, eliciting disappointment or anger when the partner fails to meet these expectations.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to lay the descriptive groundwork for how ambivalent sexism relates to close relationship partner ideals in different cultures. Our purpose was to examine how individuals’ endorsement of the above prescriptions and proscriptions correlated with ambivalent gender ideologies in two different cultures known to differ in their understanding of romantic love and experiences of gender disparity. As such, we take a primarily descriptive approach to the current study, tailored to the qualitatively different ideals held by men and women, American and Chinese.

An advantage of the current research is that it examines ambivalent sexism at the level of valence: To our knowledge, no study has investigated the role of benevolent and hostile ideologies on both sides of close relationships. Most prior studies have explored only BS and HS, that is, just sexism toward women. Because heterosexual close relationships entail people of both genders, accounts of both BS and BM are necessary to address fully the role of benevolence, and likewise, both HS and HM to address the role of hostility.

Because our overall research question is about the patterns of how benevolence and hostility relate to these ideals, whatever form they may take for each group, our hypotheses, and by extension, our analyses, do not compare across groups, but are specific to each group. This strategy is useful for understanding the overall picture of how influential ambivalent sexism is in shaping people’s relationship ideals, above and beyond income affordances. (However, we also conducted parallel analyses to see how culture moderates common concerns for Americans and Chinese. We present the latter results in shorter form in the Results Section.) For our primary investigation of the relationship between ambivalent sexism and group-specific relationship ideals, we summarize our hypotheses below.

Summary of Hypotheses

-

1.)

Because hostile gender ideologies are rooted in gender differences in societal power that allow the culturally dominant group to exercise more power in heterosexual relationships, hostile ideologies should relate to (both American and Chinese) men’s ideals (e.g., prescriptions for a non-threatening or meek partner and proscriptions against a successful or ambitious partner). This relationship should emerge controlling for benevolent ideologies and income.

-

2.)

Because benevolent ideologies present positive, prosocial depictions of the target, and because the subordinated group is more likely to accept them than hostile ideologies, benevolent ideologies should relate to (both American and Chinese) women’s ideals (e.g., prescriptions for a romantic or strong male partner and proscriptions against a feminine partner). This relationship should emerge controlling for hostility and income.

-

3.)

Because close relationships ideals are conditioned by cultural beliefs in romantic love, benevolent ideologies should relate to Americans’ partner ideals (e.g., prescriptions for a partner who fulfills the traditional gender role: romantic or strong male partner, and warm or nice female partner). This relationship should emerge controlling for hostility and income.

-

4.)

Because gender disparity is relatively high in China, hostile ideologies should be particularly salient, and hostile ideologies should relate to Chinese partner ideals (e.g., proscriptions against what they especially do not want in their partner; for men, proscriptions against a successful or ambitious partner; for women, proscriptions against a domineering partner) This relationship should emerge controlling for benevolence and income.

Organized by participant gender, we expected American men’s ideals to relate to both hostile sexism (H1) and benevolent sexism (H3), American women’s ideals to relate to benevolent sexism (H2 and H3 above), Chinese men’s ideals to relate to hostile sexism (H1 and H4), and Chinese women’s ideals to relate to both benevolent sexism (H2) and hostile sexism (H4).

As we are interested in understanding the unique contributions of benevolence and hostility to explaining people’s relationship ideals, we will test these predictions through multiple regressions analyses, entering benevolent and hostile ideologies as independent variables and each prescription or proscription as a dependent variable, and controlling for income, for each of our four groups.

Method

Participants

To obtain an American sample, 311 Princeton undergraduates (122 men, 188 women, 1 unspecified) volunteered to complete a relationship questionnaire, responding to an emailed invitation sent to 1000 randomly selected Princeton University accounts. The invitations offered a cash prize (one of five drawing prizes at $50 each), as in the preliminary study. Participants’ relationship statuses again were evenly distributed among: single and never seriously attached (21.54%), single and previously in serious relationship (27.33%), or currently in serious relationship (27.65%). The rest were either currently in a casual relationship (11.25%) or did not indicate their status (12.22%). White participants made up 59.49% of the sample; Asian participants, 15.43%; Black participants, 5.79%; another race, 6.75%; and the rest were unspecified (12.54%).

To obtain a Chinese sample, 290 undergraduates (166 men, 120 women, 4 unknown) from Wuhan University completed the survey for course credit. Relationship statuses were as follows: Many were single and never seriously attached (47.93%), although many others were currently in a serious relationship (28.62%), with the remainder single and previously in a serious relationship (14.14%), currently in a casual relationship (8.28%), or unspecified (1.03%).

Questionnaire and Procedure

The study was described as a 15-minute study that was described as examining people’s expectations and understandings of close romantic heterosexual relationships. In the first part of the study, participants rated the importance of relationship ideals (prescriptions and proscriptions) and then completed a survey on “opinions about gender relations” (ASI and AMI inventories).

Prescriptions and Proscriptions

To determine common gender prescriptions and proscriptions in relationships, we previously surveyed 716 undergraduates at two American colleges (211 men, 301 women, 204 unknown) about their relationship ideals for an other-sex partner using a free-response format. Regardless of their own gender, participants provided free responses to four questions regarding an ideal, romantic partner in a heterosexual relationship: what men and women each should be like (prescriptive) and should not be like (proscriptive). But note that in all instances, participants described an ideal partner in a heterosexual relationship to assess relationship ideals and norms. We did not assess participants’ sexual orientation because we specified that the study concerned heterosexual relationships. From this survey, we ended up a list of 85 prescriptions and 97 proscriptions to use in the current study.

These prescriptive and proscriptive ideals were then included in the current research. Based on their own experiences, participants rated the importance (1 = Not at all important; 5 = Extremely important) for an ideal partner to possess each prescription and not to possess each proscription. Immediately prior to each list of prescriptions and proscriptions, participants identified their gender. We included this so that participants would be mindful of relationship gender roles and more readily provide gender-intensified expectations they held for their ideal partner.

Using principal components extraction and varimax rotation, we factor analyzed participants’ ratings of prescriptions and proscriptions in each of the four participant groups (American women and men, Chinese women and men). We factor analyzed items within each of these groups, as opposed to combining across gender or culture, because we wanted to investigate how sexism shapes people’s relationship ideals. Our purpose here is to be as culturally sensitive as possible, by developing a relevant description of each cultural and gender group’s own dimensions. That is, we wanted to retain, and rely on, cultural differences in the content of relationship ideals, if any, and not presume that factors derived an American sample would generalize. This analysis strategy yielded different sets of prescriptions and proscriptions for each of the four groups. Therefore, we did not make direct comparisons across groups but investigated how many, and the particular types, of ideals that related to benevolent and hostile sexism, within each group. The list of items for each prescription and proscription for each group are presented in Appendices C-J.

Ambivalent Sexism

Shortened versions of the ASI and AMI scales occupied the second half of the survey. The original scales were shortened to 12 items each (Appendices A and B), by selecting items with the highest individual performance across many samples in previous studies by the second and third authors and their colleagues, as well as with a goal to preserve representation of all three theoretical domains (heterosexual intimacy, power, and role differentiation) of ambivalent sexism. Chinese versions were translated and back-translated.

The ASI and AMI scales achieved good reliabilities, α = .86 and α = .82, respectively, among the American sample, and acceptable reliabilities, α = .68 and α = .65, among the Chinese sample. Benevolent ideology scores were calculated by adding the twelve items in the BS and BM subscales; likewise for hostile ideology scores, by adding HS and HM.

Analysis Strategy

Recall that the current research focuses on the differential role of benevolent and hostile gender ideologies. The main analyses correspondingly looked at how benevolence (BS and BM together), and hostility (HS and HM together), guide people’s ideals. For each of the four participant groups, a series of multiple regressions analyses used benevolent and hostile ideologies as independent variables, controlling for income, and participants’ endorsement of each prescription or proscription as a dependent variable. These analyses revealed the unique contributions of benevolence and hostility to explaining people’s relationship ideals. While some make decisions based on ideological beliefs, other people may be guided more by practicality and life situations. We controlled for income because we wanted to partial out economic affordances to make demands of a close relationship partner and examine only the demands explained by gender ideology.

Results

Descriptives

The ASI and AMI scales correlated strongly in both the American, r(271) = .73, p < .001, and Chinese samples, r(287) = .53, p < .001. More focal to the current research, benevolent and hostile ideologies correlated strongly for both Americans, r(271) = .70, p < .001, and Chinese, r(288) = .74, p < .001.

Controlling for income, a 2(gender) X 2(country) multivariate analysis of variance on the two attitudes types (benevolent, hostile) revealed multivariate main effects of gender, Wilks’ λ = .98, F(2, 539) = 5.17, p < .01, η2 = .02, and country, Wilks’ λ = .54, F(2, 539) = 229.32, p < .001, η2 = .46, as well as an interaction, Wilks’ λ = .97, F(2, 539) = 9.13, p < .001, η2 = .03. Men scored higher than women on both benevolence (M Men = 30.82; M Women = 26.14) and hostility (M Men = 32.22; M Women = 27.39). And, Chinese scored higher than Americans on both benevolence (M Chinese = 34.51; M American = 21.78) and hostility (M Chinese = 37.45; M American = 21.32). But the interaction effect emerged only for benevolent attitudes. See Table 1 for group means.

Within country, American men (M = 24.49) outscored women (M = 19.96) on benevolent attitudes, t(271) = 3.37, p < .01, but there was no gender difference for hostile attitudes. Contrary to the American sample, there was no gender difference among the Chinese sample for benevolent attitudes, but Chinese men (M = 38.53) outscored women (M = 35.96) on hostility, t(284) = 3.07, p < .01.

American Men’s Close Relationship Preferences

Factor analyses for American men produced four prescriptions and four proscriptions. They include a Warm partner (e.g., “Kind,” “Considerate”), Traditional (Female) partner (e.g., “Good home-maker,” “Holds traditional values”), Attractive partner (e.g., “Good-looking,” “Attractive”), and Strong partner (e.g., “Protects me,” “Values equality”). Proscriptive factors include an Abusive partner (e.g., “Emotionally Abusive,” “Cold”), an overly Feminine partner (e.g., “Too Feminine,” “Too girly”), Unattractive partner (e.g., “Unattractive,” “Too fat”), and Not Traditional (e.g., “Lacks religious values,” “Vulgar”). A MANOVA did not reveal that ratings of these ideals differed by relationship status, Wilks’ λ = .77, F(24, 282) = 1.08, n.s.

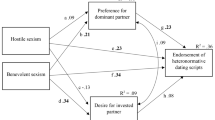

We expected American men’s ideals to relate to both hostile sexism (a gender effect per H1) and benevolent sexism (a culture effect per H3). Table 2 presents the results of multiple regressions analyses, examining how benevolent and hostile sexism, controlling for each other and income, uniquely predict people’s endorsement of each prescription and proscription. Benevolent ideologies relate to a desire for partners who are traditional: prescriptions for a Warm (β = .35) and Traditional Female (β = .50) partner, and proscription against a partner who is Not Traditional (β = .43). Hostile sexism also influences American men’s preferences; hostile men are less likely to prescribe a Warm (β = −.32) and Traditional Female (β = −.35) partner. In addition, they score marginally lower on the Abusive (β = −.27, p = .06) and Not Traditional (β = −.24, p = .09) proscriptions. Results indicate that American men are guided by ambivalent gender attitudes, supporting our first prediction that men should be guided by hostile ideologies and third prediction that benevolent ideologies should be influential for Americans as members of a culture that emphasizes romantic love in close relationships. In particular, the pattern for benevolence shows that American men high in benevolence want a partner who fits the traditional female role. The (inverse) direction of the relationship between hostility and the ideals was not expected and we return to this point in the discussion.

American Women’s Close Relationship Preferences

Analyses produced five prescriptive and six proscriptive factors. Similar prescriptive themes emerged for women as for men. The prescriptive factors concerned a Warm partner (e.g., “Someone I can confide in,” “Loves me”), Romantic partner (e.g., “Good with kids,” “Completes me”), Attractive partner (e.g., “Good-looking,” “Has nice body”), and Strong partner (e.g., “Confident,” Challenges me to be better person”) and Traditional Male partner (e.g., “Holds traditional values,” “Politically liberal (-)”). Proscriptive factors included a General Rejection factor, comprising an assortment of first-cut rejection items (e.g., “Uncaring,” “Dishonest”), and factors opposing a Feminine partner (e.g., “Cries too much,” “Too feminine”), Abusive partner (e.g., “Emotionally abusive,” “Cruel”), Jealous and Self-absorbed partner (e.g., “Jealous,” “Overly concerned about appearance”), Clingy partner (e.g., “Clingy,” “Dependent”), and Traditional Male partner (e.g., “Breadwinner,” “Too conservative”). A MANOVA to assess a possible effect of respondents’ relationship status on their ratings of these ideals revealed no effect, Wilks’ λ = .77, F(33, 440) = 1.22, n.s.

In our second and third hypotheses, we expected benevolent ideologies to guide women’s ideals, and Americans’ ideals, respectively. Consistent with these predictions, benevolence relates to seven out of these eleven factors for American women. (See Table 3 for the beta weights for each of benevolence and hostility, controlling for each other and income.) Similar to the benevolence pattern for American men, the pattern here suggests that women who endorse benevolent ideologies tend to want a traditional gender partner, as indicated by the significant relationships between benevolence and the prescriptions for a Romantic (β = .54), Strong (β = .26), and Traditional Male (β = .36) partner, as well as proscriptions against a partner who is Feminine (β = .31). A second pattern emerged such that the least benevolently sexist women are more proscriptive in their ideals, as indicated by the negative relationships with Abusive (β = −.22, p = .06), Jealous & Self-absorbed (β = −.22), and Clingy (β = −.25) proscriptions. In addition, benevolence is also associated with prescribing an Attractive partner (β = .51).

Though not predicted, hostile ideologies related negatively to two prescriptions for American women: Warm partner (β = −.26) and Romantic partner (β = −.29). The direction of the correlations makes sense, as indicating that the least hostile women are more likely to desire a partner who is warm and romantic, both characteristics relating to intimacy-seeking concerns.

Chinese Men’s Close Relationship Preferences

Factor analyses with Chinese men produced fewer factors than for the other three groups. However, the three prescriptions and two proscriptions were similar to those for the American men. The prescriptions were a Warm partner (e.g., “Respectful,” “Loves me”), Strong partner (e.g., “Independent,” “Competent”), and Attractive partner (e.g., “Has nice body,” “Good-looking”). However, note that American men’s Attractive factor included personality items, such as “sociable” and “easy-going,” while for Chinese men, attractiveness included feminine role items “nurturer” and “deferent.” Proscriptions were less clear, producing only two broad items, a General Rejection factor (e.g., “Immoral,” “Intolerant”) and Feminine partner (e.g., “Cries too much,” “Sheltered”). A MANOVA did not reveal a multivariate main effect of relationship status on endorsement of these ideals, Wilks’ λ = .93, F(15, 426) = .73, n.s.

Two predictions were tested and generally supported: that hostile ideologies would relate to men’s ideals (H1) and that hostile ideologies would relate to Chinese ideals (H4). Multiple regressions were run, testing how much benevolent and hostile sexism, controlling for each other and income, uniquely predict Chinese men’s endorsement of each prescription and proscription. These analyses yielded mostly hostility effects (See Table 4). Hostile men prescribe an Attractive partner, (β = .20, p = .05), and endorse strongly the General Rejection (β = .22) and Feminine (β = .26) proscriptions. The only significant correlation with benevolent ideologies was the prescription for a Warm partner (β = .21). Chinese men with higher hostile sexism are more demanding in their requirements for their relationship partners, especially in their proscriptions. This suggests that hostile men were more likely to rule out potential partners for having undesirable characteristics. However, there were not enough factors to see if hostility would relate specifically to prescriptions for a non-threatening or meek partner and proscriptions against a successful or ambitious partner.

Chinese Women’s Close Relationship Preferences

Factor analyses revealed five prescriptive and four proscriptive factors among Chinese women. Prescriptions were for a Warm partner (e.g., “Caring,” “Appreciates me”), Provider & Competent partner (e.g., “Has a good job,” “Competent”), Homemaker & Kind partner (e.g., “Homemaker,” “Kind”), Relationship Competent partner (e.g., “The other half of me,” “Respects my wishes”), and Attractive & Similar partner (e.g., “Striking appearance,” “Has similar religious beliefs”). Proscriptions included a General Rejection factor (e.g., “Disloyal,” “Cheats on me”), Disrespectful partner (e.g., “Disrespectful,” “Vulgar”), Possessive & Superficial partner (e.g., “Possessive,” “Vain”), and Extreme Gender Roles (e.g., “Breadwinner,” “Submissive”). A MANOVA did not reveal a significant multivariate main effect of relationship status on ratings of these prescriptions and proscriptions, Wilks’ λ = .74, F(27, 304) = 1.21, n.s.

We made two predictions that are relevant for Chinese women: benevolent ideologies should relate to women’s relationship ideals (H2) and hostile ideologies should relate to Chinese relationship ideals (H4). Therefore, for Chinese women, both benevolent and hostile attitudes should relate to their ideals, with benevolence relating to a traditional male partner ideal and hostility relating to proscribing a domineering partner. Each prescription and proscription was regressed onto benevolent ideologies, controlling for hostility and income; and then onto hostile ideologies, controlling for benevolence and income. These analyses yielded significant relationships between benevolent ideologies and Warm (β = .34) partner prescription and Possessive & Superficial (β = .38) and Extreme Gender Roles (β = .35) proscriptions. The relationship between benevolence and desiring a Warm partner and proscribing a partner who displays Extreme Gender Roles (e.g. too feminine) suggests a link between benevolent attitudes and holding as an ideal, the traditional male partner.

Hostility was related to the Possessive & Superficial (β = −.43) proscription, as well as to the Extreme Gender Roles proscription marginally, (β = −.28, p = .09). (See Table 5 for all βs.) These data did not reveal evidence that hostility would relate to resentment against a domineering partner. However, these two relationships appear to suggest that hostility relates more broadly to relationship concerns of both men and women, not just the culturally dominant men, in contexts with high gender disparity. This makes sense because hostile sexism is a specific form of group competition, and if anything, high gender disparity may make hostility toward the other gender an especially salient and powerful influence in one’s life.

An Aside on Parallel Analyses

While the above analytic strategy allowed us to understand how ambivalent sexism impacts each group-specific relationship ideals, it prevents between-group comparisons from such data, beyond eyeballing the relative percent of factors that relate to sexism. For example, given our reasoning that the culturally dominant group’s (men’s) hostile ideologies should relate to their relationship ideals, and that these ideologies are rooted in gender differences in societal power, we might suspect that hostile ideologies might more strongly guide Chinese men’s compared to American men’s partner ideals because China entails greater gender inequality than does the US. In order to more directly test for such a comparison across culture, we created two additional sets of factors, separately for men and women but collapsed across culture. Then, we factor analyzed American and Chinese women’s ratings together and likewise for American and Chinese men’s ratings. For each set of factors, we ran two series of hierarchical regression analyses. One series investigated the effects of benevolence, culture, and their interaction on each factor, controlling for income and hostility. Similarly, the other set of analyses investigated the effects of hostility, culture, and their interaction, controlling for income and benevolence. These analyses have the advantage of demonstrating where and how much culture moderates the relationship between sexism and relationship ideals.

In the interest of understanding the general patterns in these supplemental analyses, we refrain from going into detail about each factor, and summarize the role of culture as a moderator. The complete set of test statistics is available from the first author. In the ten factors that emerged for women, culture moderated the role of benevolent attitudes in six factors, and hostile attitudes in five factors. Benevolence main effects emerged for six factors, and marginal hostility main effects emerged for three, this latter part not surprising when we consider the hostility effects that emerged for Chinese women’s ideals in the main analyses.

In the eight factors that emerged for men, culture moderated only the effects of hostile attitudes, and not benevolence, for four factors. The culture moderator effects for hostility for both men and women indicate that the relationship between hostility and people’s ideals are exaggerated for the Chinese. This suggests, again, that hostility is potent not just for men but women also in a context where there is great gender disparity at the societal level.

Note that these parallel analyses explored the role of only culture and not gender as a moderator. This is because we are interested in gender-specific and gender-intensified prescriptions and proscriptions—a partner who plays the “Traditional Gender Role” means someone who cares for the children and cleans house, if one is a woman, but it means someone who is the breadwinner, if one is a man. Therefore, it would not be meaningful or useful to create and explore common factors across gender.

Discussion

The present research found that benevolent and hostile sexism each influence people’s close relationship ideals, but differently, by perceiver gender and cultural context. Both American and Chinese men’s relationship ideals were guided by hostile gender beliefs. Both American and Chinese women’s ideals were guided by benevolent beliefs. American men’s ideals also related to their benevolent beliefs, so Americans of both genders shared this belief system. These findings underscore the role of both individual-level variables (personal attitudes about gender roles, perceiver gender) and the greater social environment (cultural ideas about close relationships, gender disparity in one’s society), in the complex interplay between immediate and local contexts.

The current study has an important limitation. Participants rated the importance of prescriptions and proscriptions generated from a prior survey of an exclusively American sample. Nevertheless, we do not believe that the items were unique to Americans only, even if they may be more relevant and salient to Americans than Chinese. Our initial American sample generated a large and diverse group of items, covering a wide array of mate and relationship characteristics, many of which are already known to generalize across cultures (e.g., Eastwick et al. 2006). Beyond this point of item-generation, we took care to employ an “emic” approach to address group-specific concerns (Goodenough 1970), using separate analyses for each gender and cultural group. In addition, by taking into account how items clustered together rather than investigating them as individual traits, our analyses investigated what “profiles” (e.g., attractive) people prescribed or proscribed, rather than each specific characteristic (e.g., thin, muscular). Thus, we analyzed prescriptions and proscriptions at a broad level, rather than idiosyncrasies for Americans. Also, the finding in the parallel analyses that the gender effects of hostility and benevolence were greater when considering the Chinese sample suggests that the items generated by the American sample not only made sense to but were relevant for our Chinese participants.

The use of different prescriptions and proscriptions for each group does not allow us to make direct comparisons across groups. Instead, we supplemented these analyses with the parallel analyses which made direct comparisons and specifically tested country moderation effects. The merit of group-specific items is that they allowed us to use ideals that are important for each group, rather than either broad prescriptions and proscriptions or ones that could emerge due to the bigger subsamples, American women and Chinese men. Our main analyses remained consistent with the idea that relationship ideals are culturally normative and gender-specific.

The current study demonstrated that both hostile and benevolent gender ideologies shape close-relationship preferences. Furthermore, because they relate to both prescriptions and proscriptions, which are the rules and boundaries people set for their partners, ambivalent sexist ideologies can employ both positive and negative control strategies to structure and manage relationships. Together, gender ideologies about power and romance shape relationship ideals: Hostile ideologies are a privilege for the powerful (male) partner, and benevolent ideologies placate its (female) endorsers into accepting partners who reinforce the subordinated role.

Hostility drives sexism within close relationships by shaping the male partner’s ideals. Relationship ideals of both American and Chinese men relate to their level of hostility, but in opposite directions, suggesting that the dynamics of hostile gender beliefs depend on the level of societal power differential between men and women. Among Americans, the least hostile men were pickiest about what they looked for in a partner. Perhaps highly hostile American men have less intense partner requirements because either they do not take a sincere interest in close relationships or they are pessimistic about relationships, such that they disengage from them. Or perhaps people who are least hostile are most interested in these ideals that facilitate relationship building. This explanation may apply to the negative relationships between hostility and relationship ideals found also for American women and Chinese women. At this point, these are speculations, which may be fertile grounds for future research. In contrast to American men, Chinese men’s hostility increased their relationship demands. We speculate that, having greater societal power (relative to women), Chinese men may feel freer to enjoy the perks of being the dominant partner who has the power to demand what he wants or to reject potential partners. Common to both cultures, however, is that hostile intergroup attitudes, usually associated with the public sphere, seep into close relationships when the culturally dominant group members (men) rely on them to guide relationship concerns and expectations, in some cases, providing an overt control mechanism for one’s partner.

Benevolent gender ideologies promote and maintain gender inequality in relationships by shaping partner ideals, especially those of women and people in cultures that experience relationships as romantic love. Benevolent ideologies, one function being to establish intimacy in close relationships, depict positive images (though lesser status) of women, thereby making it easier to accept those beliefs and influence women’s ideals of a partner. Further, because of benevolent gender ideologies’ associations with romantic ideations of one’s partner, and because cultures vary in the extent to which they endorse such romantic depictions, cultural distinctions, particularly between East and West, emerged when examining benevolence’s role, with Americans (both genders, compared to only women in China) more likely to be guided by benevolent ideologies. Consequently, benevolent ideologies guided more of American participants’ relationships preferences even though, relative to the Chinese, American respondents were less likely to endorse benevolently sexist attitudes (reflecting a generally more gender-egalitarian culture). These findings underline the difference between examining group means and analyzing correlations.

A concurrent study investigating marriage preferences and norms shows some similar results (Chen et al. 2009). It differed in many crucial respects: (a) the explicit context for participants was power-related gender roles in marriage and marital courtship, a “Dating and Marriage Values Survey,” (b) using a different set of a priori items from prior Chinese surveys, (c) focusing specifically on own criteria (not one’s ideals for both one’s own and the other gender, as here), (d) factor-analyzing the items all together and forcing a single solution across genders and cultures, to make intergroup comparisons, (e) examining only desired (not undesired) characteristics, and (f) not including the AMI. Despite all these method differences, four main results replicate. Sexism scores again are higher, first, in China and, second, in men. Third, hostile sexism predicts more of men’s compared to women’s mate-selection criteria. An entirely separate questionnaire in Chen et al., the gender-related ideology in marriage (GRIM) scale, showed mainly results of hostile sexism, interpreted as men’s willingness to express hostile sexism, after courtship and once married. Fourth, benevolent sexism again predicts selecting a traditional mate for the American sample, both genders (although the small male effect was nonsignificant, due to a small sample in Chen et al., a third the current sample’s size). However, contrary to the current study, the same result occurred for the Chinese sample, including men. This broader benevolence-traditionalism result in the Chen at al. sample probably comes from the explicitly marital context of the mate-selection criteria. But the other several mate-selection results were parallel, complementing the current American-generated items by using Chinese-generated items.

By itself, the current study showed that benevolent and hostile attitudes have in common a similar function: Together, they promote the gender status quo and uphold traditional gender roles by prescribing characteristics of a traditional partner and proscribing characteristics that threaten conventional gender roles, with certain contexts—here, gender disparity and culture—further exaggerating their impact. The enforcement of traditional roles occurs not just within the public sphere (e.g., the workplace), but in the private sphere as well. Cultural ideals of who men and women “should be” powerfully shape heterosexual romantic partner preferences, linking romance with inequality.

References

Abrams, D., Viki, G. T., Masser, B., & Bohner, G. (2003). Perceptions of stranger and acquaintance rape: The role of benevolent and hostile sexism in victim blame and rape proclivity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 111–125.

Barreto, M., & Ellemers, N. (2005). The burden of benevolent sexism: How it contributes to the maintenance of gender inequalities. European Journal of Social Psychology, 35, 633–642.

Begany, J. J., & Milburn, M. (2002). Psychological predictors of sexual harassment: Authoritarianism, hostile sexism, and rape myths. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 3, 119–126.

Berscheid, E., & Meyers, S. A. (1996). A social categorical approach to a question about love. Personal Relationships, 3, 19–43.

Brehm, S. S. (1992). Intimate relationships. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Burgess, D., & Borgida, E. (1999). Who women are, who women should be: Descriptive and prescriptive gender stereotyping in sex discrimination. Psychology, Public Policy, and the Law, 5, 665–692.

Buss, D. M., & Shackelford, T. K. (2008). Attractive women want it all: Good genes, economic investment, parenting proclivities, and emotional commitment. Evolutionary Psychology, 6, 134–146.

Chen, Z., Fiske, S. T., & Lee, T. L. (2009). Ambivalent sexism and power-related gender-role ideology in marriage. Sex Roles, 60, 765–778.

Christopher, A. N., & Mull, M. S. (2006). Conservative ideology and ambivalent sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30, 223–230.

Dion, K. K., & Dion, K. L. (1993). Individualistic and collectivistic perspectives on gender and the cultural context of love and intimacy. Journal of Social Issues, 49, 53–69.

Dion, K. K., & Dion, K. L. (1996). Cultural perspectives on romantic love. Personal Relationships, 3, 5–17.

Eastwick, P. W., Eagly, A. H., Glick, P., Johannesen-Schmidt, M., Fiske, S. T., Blum, A., et al. (2006). Is traditional gender ideology associated with sex-typed mate preferences? A test in nine nations. Sex Roles, 54, 603–614.

Feather, N. T. (2004). Value correlates of ambivalent attitudes toward gender relations. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 30, 3–12.

Glick, P., Diebold, J., Bailey-Werner, B., & Zhu, L. (1997). The two faces of Adam: Ambivalent sexism and polarized attitudes toward women. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 1323–1334.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The ambivalent sexism inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1997). Hostile and benevolent sexism: Measuring ambivalent sexist attitudes toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21, 119–135.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1999). The ambivalence toward men inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent beliefs about men. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 519–536.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). Ambivalent sexism. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 33, pp. 115–188). Thousand Oaks: Academic.

Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J. L., Abrams, D., Masser, B., et al. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 763–775.

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., et al. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 713–728.

Glick, P., Sakalli-Ugurlu, N., Ferreira, M. C., & de Souza, M. A. (2002). Ambivalent sexism and attitudes toward wife abuse in Turkey and Brazil. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 292–297.

Goodenough, W. H. (1970). Describing a culture. Description and comparison in cultural anthropology (pp. 104–119). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Goodwin, S. A., Fiske, S. T., Rosen, L. D., & Rosenthal, A. M. (2002). The eye of the beholder: Romantic goals and impression biases. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 232–241.

Hsu, F. L. K. (1981). Americans and Chinese: Passage to differences (3rd ed.). Honolulu: The University Press of Hawaii.

Johannesen-Schmidt, M. C., & Eagly, A. H. (2002). Another look at sex differences in preferred mate characteristics: The effects of endorsing the traditional female gender role. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 322–328.

Jost, J. T., & Kay, A. C. (2005). Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: Consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 498–509.

King, M. P., (Writer) & Van Patten, T. (Director). (2004). An American girl in Paris (part deux). In J. Rottenberg & E. Zuritsky (Producers), Sex and the city. New York: HBO.

Kephart, W. M. (1967). Some correlates of romantic love. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 29, 470–474.

Kurzban, R., & Weeden, J. (2005). Hurrydate: Mate preferences in action. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26, 227–244.

Levine, R., Sato, S., Hashimoto, T., & Verma, J. (1995). Love and marriage in eleven cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 26, 554–571.

Masser, B. M., & Abrams, D. (1999). Contemporary sexism: The relationships among hostility, benevolence, and neosexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 23, 503–517.

Masser, B. M., & Abrams, D. (2004). Reinforcing the glass ceiling: The consequences of hostile sexism for female managerial candidates. Sex Roles, 51, 609–615.

Pimentel, E. E. (2000). Just how do I love thee?: Marital relations in urban China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62, 32–47.

Prentice, D. A., & Carranza, E. (2002). What women and men should be, shouldn’t be, are allowed to be, and don’t have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26, 269–281.

Riley, N. E. (1994). Interwoven lives: Parents, marriage, and Guanxi in China. Journal of Marriage and Family, 56, 791–803.

Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2001). Prescriptive gender stereotypes and backlash toward agentic women. Journal of Social Issues, 57, 743–762.

Rudman, L. A., & Heppen, J. B. (2003). Implicit romantic fantasies and women’s interest in personal power: A glass slipper effect? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1357–1370.

Sakalli-Ugurlu, N., & Glick, P. (2003). Ambivalent sexism and attitudes toward women who engage in premarital sex in Turkey. The Journal of Sex Research, 40, 296–302.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology Vol. 25 (pp. 1–65). Orlando: Academic.

Sibley, C. G., & Wilson, M. S. (2004). Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes toward positive and negative sexual female subtypes. Sex Roles, 51, 687–696.

Simpson, J., Campbell, B., & Berscheid, E. (1986). The association between romantic love and marriage: Kephart (1967) twice revisited. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 12, 363–372.

Sprecher, S., Aron, A., Hatfield, E., Cortese, A., Potapova, E., & Levitskaya, A. (1994). Love: American style, Russian style, and Japanese style. Personal Relationships, 1, 349–369.

Stafford, L., & Canary, D. J. (1991). Maintenance strategies and romantic relationship type, gender and relational characteristics. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 8, 217–242.

Tiedens, L. Z. (2001). Anger and advancement versus sadness and subjugation: The effect of negative emotion expressions on social status conferral. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 86–94.

United Nations Development Programme. (2005). Human development report 2005. New York: Oxford University Press.

Viki, G. T., & Abrams, D. (2002). But she was unfaithful: Benevolent sexism and reactions to rape victims who violate traditional gender role expectations. Sex Roles, 47, 289–293.

Viki, G. T., Abrams, D., & Hutchison, P. (2003). The “true” romantic: Benevolent sexism and paternalistic chivalry. Sex Roles, 49, 533–537.

Wang, C. D., & Mallinckrodt, B. S. (2006). Differences between Taiwanese and U.S. cultural beliefs about ideal adult attachment. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 53, 192–204.

Acknowledgements

We thank Andrew Conway for his helpful advice on statistical analyses and Blair Moorhead for her help in coding data. We are also grateful to James Chu of Princeton University’s Office of Information Technology for his assistance in collecting open-ended data. This research was supported partially by a grant from Chinese National Social Science Foundation (09BSH045) and Culture and Social Science Foundation of Ministry of Education of China (08JA630027) for the fourth author.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Appendix

Appendix

Appendix A

Ambivalent Sexism Inventory

Chinese version:

-

1.

很多女人拥有男人缺乏的纯洁品质。(B)

-

2.

女人应该受到男人的宠爱和保护。(B)

-

3.

女人试图通过控制男人来获得权力。(H)

-

4.

每个男人都应该有一个他爱慕的女人。(B)

-

5.

没有女人的男人不完整。(B)

-

6.

女人往往夸大她们在工作中的问题。(H)

-

7.

女人一旦得到男人对她的承诺, 就希望把他成天圈住。(H)

-

8.

当女人在与男人的公平竞争中失利时, 她们总抱怨自己受到了性别歧视。(H)

-

9.

许多女人喜欢戏弄男人, 她们让男人觉得似乎可以得到她, 然后又拒绝他。(H)

-

10.

女人比男人往往有更高的道德感。(B)

-

11.

男人应该甘愿牺牲自己为女人提供经济保证。(B)

-

12.

女权主义者正向男人提出无理要求。(H)

English version:

-

1.

Many women have a quality of purity that few men possess. (B)

-

2.

Women should be cherished and protected by men. (B)

-

3.

Women seek to gain power by getting control over men. (H)

-

4.

Every man ought to have a woman whom he adores. (B)

-

5.

Men are incomplete without women. (B)

-

6.

Women exaggerate problems they have at work. (H)

-

7.

Once a woman gets a man to commit to her, she usually tries to put him on a tight leash. (H)

-

8.

When women lose to men in a fair competition, they typically complain about being discriminated against. (H)

-

9.

Many women get a kick out of teasing men by seeming sexually available and then refusing male advances. (H)

-

10.

Women, compared to men, tend to have a superior moral sensibility. (B)

-

11.

Men should be willing to sacrifice their own well being in order to provide financially for the women in their lives. (B)

-

12.

Feminists are making unreasonable demands of men. (H)

Note. All items used a 6-point scale (0 = Disagree strongly; 5 = Agree strongly). Items denoted with (B) express benevolent attitudes; items denoted with (H) express hostile attitudes.

Appendix B

Ambivalence toward Men Inventory

Chinese version:

-

1.

即便夫妇双方都有工作, 在家里妻子也应多照顾丈夫。(H)

-

2.

男人“帮助”女人往往是为了显示他们比女人强。(H)

-

3.

每个女人都需要一个珍爱自己的男人。(B)

-

4.

如果没有一段忠诚、长期的爱情, 女人的一生就不完整。(B)

-

5.

男人生病时简直像个孩子。(H)

-

6.

男人总是争取比女人在社会上拥有更多权力。(H)

-

7.

男人可以为女人提供经济保障。(B)

-

8.

即便是那些声称自己尊重女性权利的男人, 他们其实也想要一个妻子在家里履行绝大部分家务、照顾孩子的传统夫妻关系。(H)

-

9.

男人更愿意冒着危险去帮助他人。(B)

-

10.

一旦失去身份地位, 很多男人真像孩子。(H)

-

11.

男人比女人更喜欢冒险。(B)

-

12.

一旦拥有权力和机会, 很多男人都会对女人进行性骚扰, 即使仅仅是微妙的骚扰。(H)

English version:

-

1.

Even if both members of a couple work, the woman ought to be more attentive to taking care of her man at home. (B)

-

2.

When men act to “help” women, they are often trying to prove they are better than women. (H)

-

3.

Every woman needs a male partner who will cherish her. (B)

-

4.

A woman will never be truly fulfilled in life if she doesn’t have a committed, long-term relationship with a man. (B)

-

5.

Men act like babies when they are sick. (H)

-

6.

Men will always fight to have greater control in society than women. (H)

-

7.

Men are mainly useful to provide financial security for women. (B)

-

8.

Even men who claim to be sensitive to women’s rights really want a traditional relationship at home, with the woman performing most of the housekeeping and child care. (H)

-

9.

Men are more willing to put themselves in danger to protect others. (B)

-

10.

When it comes down to it, most men are really like children. (H)

-

11.

Men are more willing to take risks than women. (B)

-

12.

Most men sexually harass women, even if only in subtle ways, once they are in a position of power over them. (H)

Note. All items used a 6-point scale (0 = Disagree strongly; 5 = Agree strongly). Items denoted with (B) express benevolent attitudes; items denoted with (H) express hostile attitudes.

Appendix C

American Men’s Prescriptive Ideals

Appendix D

American Men’s Proscriptive Ideals

Appendix E

American Women’s Prescriptive Ideals

Appendix F

American Women’s Proscriptive Ideals

Appendix G

Chinese Men’s Prescriptive Ideals

Appendix H

Chinese Men’s Proscriptive Ideals

Appendix I

Chinese Women’s Prescriptive Ideals

Appendix J

Chinese Women’s Proscriptive Ideals

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, T.L., Fiske, S.T., Glick, P. et al. Ambivalent Sexism in Close Relationships: (Hostile) Power and (Benevolent) Romance Shape Relationship Ideals. Sex Roles 62, 583–601 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9770-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9770-x