Abstract

The Madonna-Whore Dichotomy (MWD) denotes polarized perceptions of women in general as either “good,” chaste, and pure Madonnas or as “bad,” promiscuous, and seductive whores. Whereas prior theories focused on unresolved sexual complexes or evolved psychological tendencies, feminist theory suggests the MWD stems from a desire to reinforce patriarchy. Surveying 108 heterosexual Israeli men revealed a positive association between MWD endorsement and patriarchy-enhancing ideology as assessed by Social Dominance Orientation (preference for hierarchical social structures), Gender-Specific System Justification (desire to maintain the existing gender system), and sexist attitudes (Benevolent and Hostile Sexism, Sexual Objectification of Women, and Sexual Double Standards). In addition, MWD endorsement negatively predicted men’s romantic relationship satisfaction. These findings support the feminist notion that patriarchal arrangements have negative implications for the well-being of men as well as women. Specifically, the MWD not only links to attitudes that restrict women’s autonomy, but also impairs men’s most intimate relationships with women. Increased awareness of motives underlying the MWD and its psychological costs can help practice professionals (e.g., couple therapists), as well as the general public, to foster more satisfying heterosexual relationships.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In Camerino’s (c. 1400) painting, The Madonna of Humility with the Temptation of Eve, the Virgin Mary—representing chastity and purity—holds the infant Jesus, while below Eve lies naked with a serpent and fur around her hips and legs, representing sexual lust and temptation (Dunlop 2002). Polarized representations of women in general as either “good” (chaste and pure) Madonnas or “bad” (promiscuous and seductive) whores can be traced from the ancient Greeks (Pomeroy 1975) through later Western literature (Delany 2007; Gottschall et al. 2006), art (Haxell 2000), as well as contemporary films (Erb 1993; Paul 2013) and television series (Tropp 2006). Still prevalent in the West (Faludi 2009; Macdonald 1995; Munford 2007), this dichotomy also occurs in non-Western cultures—in Latin and South America (Stevens 1973) and in the Middle East and East Asia (Sev'er and Yurdakul 2001; Wright 2010)—where female chastity is integral to family honor. In the present study we assessed Israeli men’s endorsement of the Madonna-Whore Dichotomy (MWD; Tanzer 1985), and we tested its relationship to (a) motivation to reinforce patriarchy and (b) relationship satisfaction with heterosexual partners.

Theoretical Perspectives on the MWD

Freud originally coined the Madonna-whore complex (1905, 1912), theorizing that it inhibited heterosexual men’s ability to view the “tender” and “sensual” dimensions of women’s sexuality as united, rather than opposing (Hartmann 2009). Men suffering from this complex can become aroused only when they degrade a partner, reducing her to a sex object, because a respected partner cannot be fully desired. Freud located the Madonna-whore complex’s roots in men’s unresolved sensual feelings toward their mothers, leading to sexual (Hartmann 2009; Kaplan 1988) and relationship (Josephs 2006; Silverstein 1998) dysfunctions. Critics have argued that viewing these attitudes as a psychopathology ignores how culture and social structure shape men’s beliefs about women (Welldon 1992). Further, the psychoanalytic view rests on case studies (Hoffman 2009) rather than on more rigorous research methods (Chodoff 1966; Gottschall et al. 2006; but cf. Bornstein 2005).

By contrast, evolutionary psychologists (e.g., Buss and Schmitt 1993; Symons 1979; Wright 2010) view the MWD as reflecting adaptations to men’s reproductive role. MWD attitudes allegedly evolved to address paternity uncertainty (doubt about whether children by female partners are their own by focusing on cues to women’s sexual promiscuity versus faithfulness; Buss and Schmitt 1993). To avoid investing in others’ offspring, men view only faithful women as potential long-term mates, with promiscuous women representing short-term mating opportunities (with no investment in any offspring). Men therefore objectify promiscuous women to avoid emotional attachment, treating them with contempt. By contrast, emotional attachment to faithful, long-term mates creates a pair bond for cooperative child-rearing. Supporting this reasoning, promiscuity cues (e.g., past sexual experience) increased heterosexual men’s attraction to women as short-term mates, but decreased attraction to women as long-term mates (Buss and Schmitt 1993). Critics fault this evolutionary account for ignoring cultural variations and how power structures affect attitudes about sexuality (Campbell 2006; Fausto-Sterling et al. 1997).

Consistent with feminist theories, we test a third approach, viewing the MWD as an ideology designed to reinforce patriarchy. Building on Tavris and Wade (1984), we conceptualize the MWD as encompassing two inter-related beliefs: (a) polarized views that women fit into one of two mutually exclusive types, Madonnas or Whores (e.g., women are either sexually attractive or suited to being wives/mothers), and (b) an implicit personality theory associating sexual women with negative traits (e.g., manipulativeness) and chaste women with positive traits (e.g., nurturance).

Feminist scholars (Conrad 2006; De Beauvoir 1949; Forbes 1996; Tanenbaum 2000; Wolf 1997; Young 1993) have argued that the MWD reinforces unequal gender roles, limiting women’s self-expression, agency, and freedom by defining their sexual identities as fitting one of two rigid social scripts. Sexual script theory (Gagnon and Simon 1973) proposes that internalized cultural messages about sexuality, such as the MWD, determine sexual choices and behaviors (Frith and Kitzinger 2001; Jones and Hostler 2002; Simon and Gagnon 1986). The MWD meshes conventional scripts that men should act as sexual initiators and women as careful gatekeepers (Frith 2009), limiting women’s sexual agency (Frith and Kitzinger 2001). The MWD pressures women to follow the chaste path or be seen as unsuitable wives and mothers (Fassinger and Arseneau 2008). Welles (2005) found that women’s concerns about getting a “bad” sexual reputation (risking their perceived morality and men’s protection) predicted shame about their sexual desires. Shame about sexual desire reduces women’s sexual agency and puts women’s mental, physical, and sexual health at risk (Tolman and Tolman 2009).

Assertive female sexuality represents a potential source of power over men: As gatekeepers to heterosexual activity (Kane and Schippers 1996) men fear women’s ability to use sexual allure as a manipulative tactic to “unman” them (Glick and Fiske 1996; Segal 2007). Hence, by discouraging female sexual agency, the MWD mitigates a perceived threat. In fact, men penalize women who assert sexual agency (Infanger et al. 2014) just as they do women who assert power in other ways (e.g., agentic female leaders; Rudman et al. 2012). Research supports that these penalties reflect dominance motives: Men high in social dominance orientation (i.e., who prefer a hierarchical social structure; Pratto et al. 1994) are especially likely to punish sexually agentic women (Fowers and Fowers 2010).

If the MWD reflects motivation to perpetuate patriarchy, MWD endorsement should correlate with established hierarchy-enhancing and patriarchy-justifying beliefs. Social dominance orientation (Pratto et al. 1994) represents the broader motivation to preserve hierarchy between groups. More particularly, gender-specific system justification beliefs (Jost and Kay 2005) rationalize and support existing gender arrangements. Thus, we expected MWD endorsement to correlate positively with both men’s social dominance orientation (Pratto et al. 1994) and their gender-specific system justification beliefs (Jost and Kay 2005) (Hypothesis 1).

Gender inequality is also reinforced through sexist attitudes about women. Most relevant to the MWD, ambivalent sexism theory posits that sexist attitudes encompass a similar polarization between “good” and “bad” women (Glick and Fiske 1996) based on two complementary ideologies: benevolent and hostile sexism. Benevolent sexism targets women viewed as warm and supportive, who therefore deserve men’s protection and provision, whereas hostile sexism targets women viewed as competitors who seek to gain dominance and control over men. These ideologies positively correlate (Glick et al. 2000), suggesting a coordinated “carrot and stick” approach to maintaining patriarchal arrangements by rewarding women who embrace conventional gender roles and hierarchy and punishing women who challenge them (Glick and Fiske 2001; see also Jackman 1994).

Although ambivalent sexism theory, like the MWD, proposes polarized perceptions of women, we view the MWD as a distinct (though related) construct. Unlike the MWD, ambivalent sexism theory and its measurement have not directly focused on women’s sexuality. Rather, the Benevolent and Hostile Sexism subscales of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (Glick and Fiske 1996), highlight perceived gender complementary (e.g., "Every man ought to have a woman whom he adores") versus competition (e.g., "Women seek to gain power by getting control over men"). Although the Benevolent Sexism subscale includes one item suggesting that women have a “purity” men do not possess, the item does not refer specifically to sexuality. Only one Hostile Sexism item directly addresses women’s sexuality, suggesting that women tease men with the prospect of sex, later denied, to control them. However, even this item differs from the MWD, which alleges promiscuity rather than false promises of sex. Thus, although we view the MWD and Ambivalent Sexism Inventory as related (because both reflect polarized images of conventionally “good” versus “bad” women), we view them as separate constructs.

Across nations, both Benevolent and Hostile Sexism correlate with structural gender inequality, in line with the theoretical claim that they both reflect and perpetuate the existing gender system (Glick et al. 2000, 2004). Further, Sibley and Wilson (2004) showed that male participants expressed increased Hostile Sexism and decreased Benevolent Sexism toward a female character depicted as promiscuous, with the reverse occurring toward a female character depicted as chaste. Thus, we expected that MWD endorsement will positively correlate with both Benevolent and Hostile Sexism, but not so strongly as to suggest they are the same constructs (Hypothesis 2). As noted in the following (see Hypothesis 5), to further demonstrate the discriminant validity of the MWD, we assess whether its association with the variables of interest persists after controlling for Ambivalent Sexism scores.

Sexual objectification represents another related construct; the MWD serves to justify which women (i.e., the “whores”) “deserve” to be objectified. Sexual objectification refers to focusing on women’s bodies, valuing women for sexual pleasure alone, and reducing women to interchangeable instruments who exist to fulfill men’s desires (Bartky 1990; Nussbaum 1999). According to feminist theory, sexual objectification serves as a means to (re)assert men’s dominance and perpetuate women’s inferiority (Dworkin 1981; Jeffreys 2005; MacKinnon 1987). Research supports that men exposed to sexually objectified (versus non-objectified) women show more sexually harassing behaviors (Aubrey et al. 2011; Rudman and Borgida 1995), acceptance of interpersonal violence against women in sexual relationships (Aubrey et al. 2011), and endorsement of men’s superior social status (Wright and Tokunaga 2013). Thus, both the MWD and sexual objectification explicitly derogate at least some women to maintain male dominance.

Sexual double standards favor sexual activity for men but not women (Reiss 1960; see Crawford and Popp 2003, for a review). Feminist theorizing (Rubin 1975; Travis and White 2000) suggests that sexism (the desire to maintain patriarchy) motivates men to endorse sexual double standards. Specifically, Hostile Sexism mediates men’s (compared to women’s) stronger endorsement of sexual double standards (Rudman et al. 2013). Furthermore, women’s endorsement of sexual double standards diminishes willingness to acknowledge their sexual desires (Muehlenhard and McCoy 1991) or to engage in sexual communication and activities with partners (Greene and Faulkner 2005). Thus, similar to the MWD, sexual double standards control, regulate, and restrict women’s sexuality and sexual expression. Consistent with feminist theories that sexual objectification (Dworkin 1981; MacKinnon 1987) and sexual double standards (Rubin 1975; Travis and White 2000) exist to reinforce male dominance, we expected men’s MWD endorsement to correlate positively with attitudes that sexually objectify women and support for sexual double standards (Hypothesis 3).

Finally, although our conceptualization stresses MWD as a social ideology rather than individual pathology, we agree with the psychoanalytic perspective that the MWD likely diminishes men’s sexual and relationship satisfaction. Specifically, MWD beliefs should make it harder for men to be sexually attracted to women they love, or to love the women to whom they are sexually attracted.

Research supports more generally that endorsing traditional gender roles negatively affects sexual satisfaction for both men and women. Specifically, Sanchez et al. (2005) found that heterosexual men and women who embrace gender role conformity (i.e., desire to live up to gender ideals) had lower sexual satisfaction, in part due to reduced sexual autonomy. Relatedly, contrary to the perception that feminism inhibits romance, men’s feminism predicts more stable and sexually satisfying heterosexual romantic relationships (Rudman and Phelan 2007). At the societal level, greater gender equality predicts higher sexual satisfaction across cultures, perhaps because egalitarian societies place greater importance on achieving sexual pleasure and enhancing closeness through sex (Laumann et al. 2006). Thus, we expected men’s MWD endorsement to correlate positively with diminished sexual and, consequently, relationship satisfaction (see Butzer and Campbell 2008; Byers 2005; Heiman et al. 2011; Sprecher 2002; Sprecher and Cate 2004, for the link between sexual and relationship satisfaction) (Hypothesis 4).

Further, we expected that MWD will account for unique variance in men’s sexual and relationship satisfaction after controlling for Benevolent and Hostile Sexism (Hypothesis 5). Although ambivalently sexist beliefs suggest polarized views of women, unlike the MWD these beliefs do not imply that sexual pleasure and love are incompatible. MWD beliefs should therefore uniquely predict sexual and relationship dissatisfaction once ambivalently sexist beliefs are partialled out.

The Current Research

We measured MWD using a self-report questionnaire and tested Hypotheses 1–5 among heterosexual Israeli men of diverse ages. Although the hypotheses were based on findings obtained primarily among North American and West European participants, we argue that similar processes are relevant to Israeli men. First, Israeli women’s legal and socio-economic status relative to men is similar to North American and West European societies. Israel scores similarly to West European and North American countries (and differently from non-Western countries, such as nearby African and Arab states) on the United Nations’ Human Development Report’s (2016) gender development and inequality indices. Second, prior research has found similar results in Israel as compared to North America and West Europe for social dominance orientation (Levin and Sidanius 1999; Shnabel et al. 2016b), system justification (Jost et al. 2005), benevolent and hostile sexism (Shnabel et al. 2016a), sexual objectification (Moor 2010), sexual double standards (Berdychevsky et al. 2013), and sexual satisfaction (Laumann et al. 2006).

Method

Participants

A convenience sample of 111 Israeli heterosexual male volunteers were recruited via social media groups at a large Israeli university and off campus for an online questionnaire. A power analysis using the G*Power calculator (Faul et al. 2009) revealed that a sample size of 67 was sufficient for detecting medium effect sizes (ρ = .300; Cohen 1988) with a 5% significance level and power of 80%. We aimed to exceed the minimal sample size.

Three participants were excluded from analysis: one for failing a manipulation check and two for extreme responses on boxplot graphs (McClelland 2002). This left 108 participants; 52 (48%) students and the rest employed in various occupations (e.g., engineers, musicians, waiters), Mage = 28.04, SD = 8.06, range = 18–63 years-old. Specifically, 84 participants (77%) were under 30 (one participant younger than 20 and the rest in their 20s), 17 participants (16%) were in their 30s, and seven participants (7%) were 40 years or older. For relationship status, 60 participants (55%) were single, 28 participants (26%) were in a relationship, 18 participants (17%) were married, and two participants (2%) were divorced. Of the single participants, 39 (65%) reported having a serious relationship (typically a 1–3 years) in the past. Religiously, 70 participants (65%) were secular, 19 (18%) were atheist/other, 10 (9%) were religious, and nine participants (8%) did not report level of religiosity. Finally, 91 participants (84%) were born in Israel and 94 participants (87%) reported Hebrew as their native tongue.

Procedure and Measures

Participants took an online survey on “attitudes regarding various social issues.” After providing demographic information, participants completed the following measures (in Hebrew) in a randomized order (The full English research protocol is available as Online Supplement 1). All the measures (except those that were translated in previous research) were translated into Hebrew by the authors, who decided together which translation was the most accurate in the case of discrepancies. The measures were then back-translated into English by a bilingual researcher of social psychology. Comparisons were made between the original and back-translated versions, and where discrepancies existed, the authors worked with the bilingual researcher to resolve them.

MWD

We generated 12 items based on themes in prior conceptualizations about the MWD (e.g., Hartmann 2009; Tavris and Wade 1984): (a) perceptions that women’s sexuality is either very strong or very weak ("Women are typically either very liberal or very conservative sexually, but not in the middle"), (b) women’s nurturance and sexuality as mutually exclusive (e.g., "A sexy woman is usually not a good mother"), and (c) viewing sexual women has having negative, and chaste women as having positive, traits (e.g., "Women who are very interested in and liberal about sex are often problematic in terms of their personality"; "A sexually modest woman is usually a woman with good values"). As detailed in the Results section, three items were later excluded based on exploratory factor analysis (EFA); thus the final MWD scale had nine items (see Online Supplement 2 for the Hebrew version of the MWD scale). Participants rated each item on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Items were averaged such that higher scores indicated stronger MWD beliefs. The measure had good internal consistency reliability (α = .80). Evidence for discriminant validity of the MWD is reported in the Results section.

Social Dominance Orientation

Using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), participants completed a 6-item Social Dominance Orientation scale (SDO; Pratto et al. 1994; translated by Levin and Sidanius 1999), which assesses desire for social dominance and hierarchal social structures (e.g., "It's probably a good thing that certain groups are at the top and other groups are at the bottom"). Items were averaged such that higher scores indicated stronger SDO. The SDO scale has good reliability (e.g., α = .92 in a U.S. student sample, using a 16-item version; Shook et al. 2016; α = .82 in an Italian student sample, using a 10-item version; Passini and Morselli 2016). Internal consistency reliability obtained in the current study was acceptable (α = .70). The discriminant validity of the SDO scale from other attitudinal measures that predict prejudice (e.g., Right-Wing Authoritarianism), as well as its predictive validity of prejudice, have been established extensively (Pratto et al. 1994).

Gender-Specific System Justification

Using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree), participants completed a 5-item Gender-Specific System Justification questionnaire (translated by the authors from Jost and Kay 2005), which assesses legitimization of current gender relations and gender role divisions (e.g., "In general, relations between men and women are fair"). Items were averaged such that higher scores indicated stronger Gender-Specific System Justification. Internal consistency reliability obtained in the present study was good (α = .86), and similar to recent studies using U.S. community and student samples (α = .85 using an 8-item version; Calogero 2013; α = .87 using a 12-item version; Chapleau and Oswald 2014). The Gender-Specific System Justification scale represents a gender-focused rewording of the System Justification scale, which has shown convergent validity with conceptually related measures (e.g., belief in a just world) (Kay and Jost 2003).

Ambivalent Sexism Inventory

Using a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree), participants completed a 10-item version of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory (Glick and Fiske 2001; translated by Shnabel et al. 2016a). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory has been validated across cultures, showing consistent factor structure (distinct but correlated Hostile and Benevolent Sexism factors), good reliability, and predictive validity (e.g., national sample scores predict structural inequality indices; Glick et al. 2000). Although the original scale uses 22 items, shorter versions of the scale have shown similar predictive validity to the full scale and good reliability (e.g., α = .80 for a 6-item Benevolent Sexism scale and α = .85 for a 6-item Hostile Sexism scale in an Italian community sample; Rollero et al. 2014; α = .85 for a 7-item Benevolent Sexism scale and α = .81 for 7-item Hostile Sexism scale in Israeli student samples; Shnabel et al. 2016a). We used the short version of the Benevolent Sexism subscale (Rollero et al. 2014), which represents content from the full scale’s three subfactors—protective paternalism (e.g., "In a disaster, women ought to be rescued before men"), heterosexual intimacy (e.g., "Every man ought to have a woman whom he adores"), and gender differentiation (e.g., "Women, compared to men, tend to have superior moral sensibility"). Items were averaged such that higher scores indicated stronger Benevolent Sexism. The scale showed acceptable reliability in the present study (α = .78).

Hostile Sexism has a one-factor structure (Glick and Fiske 1996) and assesses a competitive view of gender relations in which women are viewed as trying to usurp male power (e.g., "Feminists are seeking for women to have more power than men"). Given its simple factor structure and to avoid respondents’ fatigue, we used a 4-item version in the present study, which still showed acceptable reliability (α = .71). Items were averaged such that higher scores indicated stronger Hostile Sexism.

Sexual Objectification of Women

Using a 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree) scale, participants completed a 13-item Men’s Objectification of Women measure (translated by the authors from Curran 2004), which included items representing three subfactors: internalized sexual objectification (e.g., "The first thing I notice about a woman is her body"), commenting about women’s bodies (e.g., "I frequently give women a rating based on attractiveness"), and looking down on unattractive women (e.g., "My friends and I tease each other about unattractive women with whom we have had romantic encounters"). Items were averaged such that overall higher scores indicated a stronger tendency to sexually objectify women. Curran (2004) reported high internal consistencies in U.S. student samples using both longer (α = .92 when using a 22-item) and shorter (α = .86 when using a 12-item) versions of the scale and good 2-week test-retest reliability (r = .88). The internal consistency reliability obtained in the present study was good (α = .82). Although convergent and predictive validity of this scale have not been established, research has demonstrated discriminant validity from sexual harassment measures (Curran 2004).

Sexual Double Standards

Participants completed the Premarital Sexual Double Standards subscale (translated by the authors from Sprecher and Hatfield 1996) of the Premarital Sexual Permissiveness scale (Sprecher et al. 1988), which is a new version of the Reiss (1964) Premarital Sexual Permissiveness scale. Because premarital sex is widely accepted nowadays for Western women (Bordini and Sperb 2013), we assessed the acceptability of sexual intercourse only at two early dating stages for which double standards still exist (Crawford and Popp 2003; Sprecher and Hatfield 1996). Using a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (utterly unacceptable) to 6 (utterly acceptable), participants indicated their agreement with the following four items: "I believe that sexual intercourse is acceptable for a [woman/man] on a first date" and "I believe that sexual intercourse is acceptable for a [woman/man] when casually dating someone (for less than one month)." To reduce social desirability bias, items referring to male and female targets appeared separately (at the beginning and the end of the study). The male-target items correlated strongly in the present study (r = .68, p < .001), as did the female-target items (r = .61, p < .001).

Participants’ Sexual Double Standards score was calculated as the averaged agreement to the two male-target items minus averaged agreement to the female-target items, such that higher scores indicated granting more sexual freedom to men than to women. A prior U.S. study using these items to measure general premarital sexual permissiveness (without separately applying them to male and female targets) reported strong internal consistency reliability of the measure (α = .85 for the 5-item version; Taylor 2005, and r = .85 for the 2-item version; Sprecher 2013). Construct validity for these items is supported by correlations with another established sexual permissiveness scale (Sprecher 2011).

Sexual Satisfaction in Relationships

Using a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (very much), participants filled out a 5-item version of the Israeli Sexual Behavior Inventory (Kravetz et al. 1999), which assesses sexual satisfaction within romantic relationships. Participants currently in a serious relationship (n = 41) were asked about their present relationships (e.g., "In general, how satisfied are you from your sex life within your current relationship?"). Participants who reported no current relationship but a serious relationship in the past (n = 38) were asked about their past relationships (e.g., "In general, how satisfied were you from your sex life within your previous relationship?"). Participants who never had a serious relationship (n = 21) or who dropped out from the study before responding to this measure (n = 8) were not asked about sexual satisfaction. Items were averaged so that higher scores indicated stronger sexual satisfaction in relationships. This measure’s construct validity has been supported through comparisons to a clinical sample with obvious sexual dysfunction and problems (Kravetz et al. 1999). Previous studies using Israeli samples reported acceptable internal consistency for a 13-item version (α = .76–.83; Birnbaum 2007, and α = .59–.77; Birnbaum and Gillath 2006) and a 7-item version (α = .75–.78; Birnbaum and Laser-Brandt 2002). However, the internal consistency reliability in the present study was not acceptable (α = .50). Hence, we excluded this measure from our analyses.

Relationship Satisfaction

Using a 6-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 6 (all the time), participants filled out a 14-item version of the Couple Satisfaction Inventory (translated by the authors from Funk and Rogge 2007). Participants currently in a serious relationship (n = 43) were asked about their present relationships (e.g., "My relationship with my partner makes me happy"). Participants who reported no current relationship but a serious relationship in the past (n = 38) were asked about their past relationships (e.g., "My relationship with my partner made me happy"). Participants who never had a serious relationship (n = 21) or who dropped-out of the study before responding to this measure (n = 6) were not asked about relationship satisfaction. Items were averaged such that higher scores indicated stronger relationship satisfaction. Previous U.S. community samples obtained high internal consistency reliability (α = .89; Cacioppo et al. 2013, and α = .95; Papp et al. 2012), as did the present study (α = .94). Previous research demonstrated strong convergent validity of the Couple Satisfaction Inventory with other measures of satisfaction and construct validity with anchor scales from the nomological net surrounding satisfaction (Funk and Rogge 2007).

Results

The data file can be accessed either through the Open Science Framework (osf.io/d9yfc) or upon email request from the first author.

Missingness Analysis

Missing values were as follows: MWD (0 participants; 0%), Social Dominance Orientation (5 participants, 4.6%), Gender-Specific System Justification (3 participants, 2.8%), Benevolent Sexism (6 participants, 5.6%), Hostile Sexism (6 participants, 5.6%), Sexual Objectification of Women (6 participants, 5.6%), and Sexual Double Standards (9 participants, 8.3%). Among participants who were currently or previously in a serious relationship and answered the Couple Satisfaction Inventory, six participants (6.9%) had missing values. Little’s MCAR test statistic (Little 1988) indicated that missing data were randomly distributed, χ2(31) = 31.42, p = .445 (Graham 2009; Schafer and Graham 2002). Given this result, we could proceed to testing the research hypotheses.

Pilot Testing: Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Prior to the present study, we conducted a pilot study using an independent sample (n = 107 heterosexual Israeli men, Mage = 26.26, SD = 4.76, range = 18–49 years-old) whose purpose was to assess the MWD factorial structure for the original 12 items (see Method section). Diagnostic tests indicated suitability for conducting EFA: the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was .86 (according to Field 2013, values between .80 and .90 are acceptable). Bartlet’s test of sphericity, χ2 (66) = 433.51, p < .001, revealed that the correlations significantly differed from zero.

A preliminary EFA using Principal Axis Factoring (PAF) suggested a single factor solution (eigenvalue for first factor = 4.85; eigenvalues for subsequent factors all < 1.14). Based on criteria suggested by Tabachnick and Fidell (2007), three items were excluded: two with low loadings across factors and one that displayed cross-loadings. We recomputed the EFA using nine items (α = .86). The scree plot suggested a unidimensional construct. The initial factor’s eigenvalue was 4.50 and explained 44.06% of variance (eigenvalues for all subsequent factors were < .83). All loadings on the first factor were > .45 (see Table 1).

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA)

We used CFA to test the MWD’s structure in the present study (n = 108). The unidimensional model fit the data well (based on guidelines from Hu and Bentler 1999; Quintana and Maxwell 1999), χ2(21) = 21.61, p = .422, χ2/df = 1.03, CFI = .997, GFI = .957, RMSEA = .016 [0, .08]. All factor loadings, presented in Table 1 were significant at p < .05. Table 1 also presents the means, standard deviations, and item-total correlations for all MWD items.

MWD Correlates with Hierarchy-Supporting Ideologies

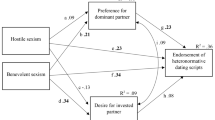

Table 2 presents means, standard deviations, and correlations between all study measures. Consistent with Hypotheses 1–3, MWD endorsement significantly correlated with Social Dominance Orientation, Gender-Specific System Justification, Benevolent Sexism, Hostile Sexism, Sexual Objectification of Women, and Sexual Double Standards. These results are consistent with feminist theorizing (e.g., Wolf 1997) that the MWD represents a patriarchy-reinforcing ideology.

MWD and Relationship Satisfaction

Table 2 also shows a negative association between the MWD and men’s Relationship Satisfaction in their romantic relationships. Thus, in line with Hypothesis 4, men scoring higher on the MWD reported feeling less satisfied in their romantic relationships. As explained in the Method, we refrained from using the Israeli Sexual Behavior Inventory due to its low reliability. Hence, we could not test the mediation model (specified in Hypothesis 4) in which MWD negatively predicts sexual satisfaction, which in turn predicts relationship satisfaction.

MWD Correlations Controlling for Ambivalent Sexism

To ensure that the associations between the MWD with Social Dominance Orientation, Gender-Specific System Justification, Sexual Objectification of Women, and Sexual Double Standards do not simply reflect the already-established associations between Ambivalent Sexism and these measures (e.g., Sibley et al. 2007), we computed partial correlations controlling for both Benevolent and Hostile Sexism. As seen in Table 2, the correlations between the MWD and these measures persisted, with all partial rs > .24, ps < .05, with the exception of Sexual Objectification of Women for which the correlation became non-significant (r = .14, p = .166). Testing Hypothesis 5, the negative correlation between the (a) MWD and (b) Relationship Satisfaction persisted when controlling for men’s (c) Benevolent and (d) Hostile Sexism (the latter is known to predict less relationship satisfaction; Hammond and Overall 2013), rab,cd = −.26, p = .025. In sum, the MWD accounts for variance in men’s endorsement of ideologies that reinforce patriarchal arrangements as well as reduced satisfaction in romantic relationships that is not accounted for by Ambivalent Sexism.

Taken together, these results help to initially establish the validity of the MWD scale. First, the correlations between the MWD and previously validated measures related to sexist and demeaning beliefs toward women support the MWD’s concurrent validity. More specifically, the MWD’s correlations with Benevolent and Hostile Sexism (which also assess polarized perceptions of women who conform versus fail to conform to conventional gender roles) support convergent validity. Importantly, the correlations between MWD and the other measures of interest generally persisted after controlling for Benevolent and Hostile Sexism (with the exception of sexual objectification), suggesting that the MWD is not redundant with these related constructs and thus supporting discriminant validity.

Additional Analyses

Given that age may covary with relationship status, we computed partial correlations controlling for age and relationship status (dummy coded such that it had the value 0 for single and 1 for non-single participants). The expected associations between the MWD and all the other measures persisted, partial rs > |.28|, ps < .05.

Also, because MWD and Sexual Double Standards scores were positively skewed, whereas Relationship Satisfaction scores were negatively skewed, we normalized scores using a log(10)-transformation (Field 2013) and conducted all analyses again (computing appropriate linear transformations prior to applying the log transformations). The expected correlations between the MWD and all the other measures persisted, rs > |.22|, ps < .05. Because the patterns of results obtained with or without the transformation were generally consistent, we report findings using raw scores, which are easier to interpret (Weston and Gore 2006).

Discussion

The present study supported the hypothesis that the MWD—a polarized perception of women in general as either chaste or promiscuous—correlates with ideologies that reinforce gender inequality, objectify women, and restrict their sexuality. Specifically, Israeli men’s MWD endorsement significantly correlated with Social Dominance Orientation, Gender-Specific System Justification, Benevolent Sexism, Hostile Sexism, Sexual Objectification of Women, and Sexual Double Standards. In addition, men who endorse the MWD reported feeling less satisfied in their romantic relationships. Finally, we demonstrated that the MWD accounted for variance in men’s patriarchy-supporting ideologies and (reduced) relationship satisfaction after controlling for Benevolent and Hostile Sexism (related constructs that reflect polarized perceptions of women more broadly).

Whereas previous theories highlighted unresolved Oedipal complexes (e.g., Hartmann 2009) or evolved mating strategies (e.g., Buss and Schmitt 1993) as antecedents of the MWD, the present study highlights the sexist, hierarchy-enhancing motives behind this dichotomized perception. As such, we offer a novel integration between social psychological and feminist theorizing, consistent with the view that the MWD reinforces ideologies that police and limit women’s sexual expression to restrict their influence and power over men (Conrad 2006; De Beauvoir 1949; Forbes 1996; Tanenbaum 2000; Young 1993) and reduce female solidarity (e.g., by encouraging engagement in “slut shaming”; Vaillancourt and Sharma 2011). That the MWD relates to patriarchy-supporting ideologies and reduced relationship satisfaction even after controlling for Ambivalent Sexism scores suggests a theoretical advance. Whereas ambivalent sexists split women into “good” and “bad” subtypes to perpetuate patriarchal arrangements (Glick and Fiske 2011), the MWD extends this polarization to attitudes about women’s sexuality.

The MWD’s unique relationship to less relationship satisfaction among men supports a contention dating back to Freud: MWD beliefs view sexual pleasure with and love for a woman as incompatible. These results are consistent with other empirical findings demonstrating that patriarchy-reinforcing beliefs have psychological costs for men. One such cost is the need to constantly defend their “manhood,” which creates a pervasive sense of threat and anxiety (Vandello et al. 2008), yet impedes acknowledgment of emotional distress, especially among other men (Cochran and Rabinowitz 2003). Ironically, although traditionally-minded men may feel less inhibited about showing vulnerability to women, MWD beliefs represent another barrier men might face. Because their relationship quality tends to be lower, traditionally-minded men, who endorse the MWD, may be less likely to seek emotional support from female partners.

Although the link between MWD and lower relationship satisfaction was proposed in early psychoanalytic theory, it had only been investigated using case studies. The current research used quantitative methods and a relatively large sample to show the negative implications MWD beliefs have for relationships. We did not directly test the psychoanalytical view that MWD beliefs reflect men’s unresolved feelings toward their mothers. However, by showing the MWD’s relationship to gender-hierarchy enhancing beliefs, our data provides support for social-cultural views (e.g., Fassinger and Arseneau 2008; Wolf 1997) that polarized attitudes toward women’s sexuality reflect a motive to reinforce patriarchal arrangements.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

The present research has several limitations. First, its correlational and cross-sectional design limits causal inference. Theoretically, social dominance orientation and system justification reflect general (and therefore more distal) motives that predispose people to hold prejudiced beliefs about specific target groups (as more proximal motives for behaviors toward those groups). For example, Sibley et al. (2007) used a longitudinal design to show that social dominance orientation predicted increases in hostile sexism over a 5-month period. Similarly, we view social dominance orientation and system justification as antecedents of the MWD. Benevolent and hostile sexism, objectification of women, and endorsement of sexual double standards, like the MWD, reflect ideologies that stem from sexist motives and whose function is to derogate and police women’s sexuality and other behaviors. Hence, all five constructs (benevolent and hostile sexism, objectification, double standards, and the MWD) correlate with each other.

Future research, however, should use experiments to strengthen causal inference. For example, researchers could expose participants to system threats (e.g., Brescoll et al. 2013) or to threats to male dominance (e.g., Rudman et al. 2012) to test the prediction that these conditions should lead to increased MWD endorsement. As for the proposed negative effect of MWD endorsement on men’s relationship satisfaction, causal inference could be strengthened by using longitudinal designs—namely, examine whether earlier MWD endorsement predicts later relationship dissatisfaction.

Another limitation of the present study relates to the measures we used. First, although our MWD measure captures the various contents composing this construct, and as such may be viewed as having high face validity, we acknowledge that the present study offers only an initial test of this measure’s construct validity. Additional research is required to fully establish its reliability and validity by testing its test-retest reliability and further validating the unidimensional factorial structure of the MWD scale in different samples via confirmatory factor analysis. Second, our measure of sexual satisfaction in relationships (i.e., the Israeli Sexual Behavior Inventory; Kravetz et al. 1999) had low reliability, which led us to exclude it from our analyses. Thus, we could not test Hypothesis 4’s suggested mediation (i.e., that MWD reduces sexual satisfaction and, in turn, relationship satisfaction). To test this hypothesis, future research could use a reliable measure of this construct such as the full 35-item version of the Israeli Sexual Behavior Inventory or alternative measures, such as the Global Measure of Sexual Satisfaction (Lawrance and Byers 1998) or Golombok-Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (Rust and Golombok 1985).

A third limitation concerns sample generalizability. First, although we believe that similar patterns are likely to be observed among men in other Western societies, we acknowledge that the construction of manhood and consequent gender system in societies characterized by intense conflict, such as Israeli society, may differ from societies with less conflict. Specifically, the need to justify violence against an adversarial outgroup promotes justifications of violence against women (Enloe 1983; Sharoni 1992). Hence, whether our findings indeed replicate in West European and North American societies awaits direct empirical examination. Second, our sample comprised a substantial proportion of undergraduates. Thus, results may be different among less educated participants who typically hold more traditional gender attitudes (Inglehart and Norris 2003; Winter 2002). Future research should aim to extend the external validity of our conclusions by examining the MWD and its correlates in more diverse samples on dimensions of ethnicity, culture, age, and education.

Practice Implications

Understanding the social psychological motivations underlying the MWD, as well as its harmful relationship implications, may be valuable for clinicians and couple therapists who treat men high on MWD endorsement. These men may have difficulties feeling attracted to the women they love, or loving the women to whom they are sexually attracted, leading to chronic dissatisfaction in their romantic relationships. More specifically, the insights provided by the present study can be integrated in therapy via psycho-educational interventions designed to reduce men’s MWD. These efforts could be modeled on existing interventions known to reduce sexism (e.g., Becker and Swim 2012). Therapists could also target the MWD’s antecedents, such as social dominance orientation, by promoting empathy and respect for other groups (e.g., Brown 2011), such as women.

The practical implications for therapists are not confined to male clients. A female client who endorses MWD beliefs or who has experienced negative reactions from a male partner due to his MWD beliefs might suffer shame or ambivalence about her own sexual desires or about her desirability. Thus, MWD beliefs may be relevant to understanding and treating the problems experienced by female clients. Further research to examine the consequences of MWD endorsement among women will be needed to pursue this speculation. On a broader social level, by shedding light on the theoretical debate regarding the MWD, our findings may increase public awareness of the harmful effects MWD ideology has for men and possibly for women as well.

Conclusions

The present study provides support for the feminist account of the MWD, sometimes viewed as alternative to the evolutionary or psychoanalytic accounts, by showing that MWD beliefs correlate with a variety of sexist and derogatory ideologies. Hence, in line with the feminist insight that “the personal is political” (Hanisch 1969), our findings suggest that seemingly individual-level concerns about promiscuity and chastity are in fact strongly related to gender power structures. In addition, that the MWD has negative consequences for men’s well-being adds to the feminist understanding (e.g., Dworkin 1981) that reducing gender inequality, and the ideologies that support it, is good for everyone—men as well as women.

References

Aubrey, J. S., Hopper, K. M., & Mbure, W. G. (2011). Check that body! The effects of sexually objectifying music videos on college men's sexual beliefs. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 55, 360–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2011.597469.

Bartky, S. L. (1990). Femininity and domination: Studies in the phenomenology of oppression. New York: Routledge.

Becker, J. C., & Swim, J. K. (2012). Reducing endorsement of benevolent and modern sexist beliefs: Differential effects of addressing harm versus pervasiveness of benevolent sexism. Social Psychology, 43, 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1027/1864-9335/a000091.

Berdychevsky, L., Poria, Y., & Uriely, N. (2013). Sexual behavior in women's tourist experiences: Motivations, behaviors, and meanings. Tourism Management, 35, 144–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.06.011.

Birnbaum, G. E. (2007). Attachment orientations, sexual functioning, and relationship satisfaction in a community sample of women. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24, 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407507072576.

Birnbaum, G. E., & Gillath, O. (2006). Measuring subgoals of the sexual behavioral system: What is sex good for? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 23, 675–701. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407506065992.

Birnbaum, G. E., & Laser-Brandt, D. (2002). Gender differences in the experience of heterosexual intercourse. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 11, 143–158.

Bordini, G. S., & Sperb, T. M. (2013). Sexual double standard: A review of the literature between 2001 and 2010. Sexuality and Culture, 17, 686–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-012-9163-0.

Bornstein, R. F. (2005). Reconnecting psychoanalysis to mainstream psychology: Challenges and opportunities. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 22, 323–340. https://doi.org/10.1037/0736-9735.22.3.323.

Brescoll, V. L., Uhlmann, E. L., & Newman, G. E. (2013). The effects of system-justifying motives on endorsement of essentialist explanations for gender differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 105, 891–908. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034701.

Brown, M. A. (2011). Learning from service: The effect of helping on helpers' social dominance orientation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41, 850–871. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00738.x.

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100, 204–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.2.204.

Butzer, B., & Campbell, L. (2008). Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15, 141–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2007.00189.x.

Byers, E. S. (2005). Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. Journal of Sex Research, 42, 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490509552264.

Cacioppo, J. T., Cacioppo, S., Gonzaga, G. C., Ogburn, E. L., & Vander Weele, T. J. (2013). Marital satisfaction and break-ups differ across on-line and off-line meeting venues. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110, 10135–10140. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1222447110.

Calogero, R. M. (2013). Objects don't object: Evidence that self-objectification disrupts women's social activism. Psychological Science, 24, 312–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797612452574.

Camerino, D. C. (c. 1400). The Madonna of humility with the temptation of Eve [Painting]. Retrieved from http://www.clevelandart.org/art/1916.795.

Campbell, A. (2006). Feminism and evolutionary psychology. In J. H. Barkow (Ed.), Missing the revolution: Darwinism for social scientists (pp. 63–99). New York: Oxford University Press.

Chapleau, K. M., & Oswald, D. L. (2014). A system justification view of sexual violence: Legitimizing gender inequality and reduced moral outrage are connected to greater rape myth acceptance. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 15, 204–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299732.2014.867573.

Chodoff, P. (1966). A critique of Freud's theory of infantile sexuality. American Journal of Psychiatry, 123, 507–518. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.123.5.507.

Cochran, S. V., & Rabinowitz, F. E. (2003). Gender-sensitive recommendations for assessment and treatment of depression in men. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 34, 132–140. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.34.2.132.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Conrad, B. K. (2006). Neo-institutionalism, social movements, and the cultural reproduction of a mentalité: Promise keepers reconstruct the Madonna/whore complex. The Sociological Quarterly, 47, 305–331. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2006.00047.x.

Crawford, M., & Popp, D. (2003). Sexual double standards: A review and methodological critique of two decades of research. Journal of Sex Research, 40, 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490309552163.

Curran, P. (2004). Development of a new measure of men's objectification of women: Factor structure test retest validity. Retrieved from psychology honors projects, digital commons @ Illinois Wesleyan university. http://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/psych_honproj/13.

De Beauvoir, S. (1949). Le deuxième sexe [The second sex]. Paris: Gallimard.

Delany, S. (2007). Writing woman: Sex, class and literature, medieval and modern. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers.

Dunlop, A. (2002). Flesh and the feminine: Early-renaissance images of the Madonna with eve at her feet. Oxford Art Journal, 25, 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxartj/25.2.127.

Dworkin, A. (1981). Pornography: Men possessing women. London: The Women's Press Limited.

Enloe, C. H. (1983). Does khaki become you? The militarization of women's lives. London: Pluto Press.

Erb, C. (1993). The Madonna's reproduction(s): Miéville, Godard, and the figure of Mary. Journal of Film and Video, 45, 40–56.

Faludi, S. (2009). Backlash: The undeclared war against American women. New York: Three Rivers Press.

Fassinger, R. E., & Arseneau, J. R. (2008). Diverse women's sexualities. In F. L. Denmark & M. A. Paludi (Eds.), Psychology of women: A handbook of issues and theories (pp. 484–508). Westport: Praeger Publishers.

Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A. G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41, 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149.

Fausto-Sterling, A., Gowaty, P. A., & Zuk, M. (1997). Evolutionary psychology and Darwinian feminism. Feminist Studies, 23, 403–418. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178406.

Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Forbes, J. S. (1996). Disciplining women in contemporary discourses of sexuality. Journal of Gender Studies, 5, 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.1996.9960641.

Fowers, A. F., & Fowers, B. J. (2010). Social dominance and sexual self-schema as moderators of sexist reactions to female subtypes. Sex Roles, 62, 468–480. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-009-9607-7.

Freud, S. (1905). Drei abhandlungen zur sexualtheorie [three essays on the theory of sexuality]. Berlin: Leipzig und Wien.

Freud, S. (1912). Über die allgemeinste erniedrigung des liebeslebens [the most prevalent form of degradation in erotic life]. Jahrbuch für Psychoanalytische und Psychopathologische Forschungen, 4, 40–50.

Frith, H. (2009). Sexual scripts, sexual refusals, and rape. In M. Horvath & J. Brown (Eds.), Rape: Challenging contemporary thinking (pp. 99–122). Devon: Willan.

Frith, H., & Kitzinger, C. (2001). Reformulating sexual script theory: Developing a discursive psychology of sexual negotiation. Theory and Psychology, 11, 209–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354301112004.

Funk, J. L., & Rogge, R. D. (2007). Testing the ruler with item response theory: Increasing precision of measurement for relationship satisfaction with the couples satisfaction index. Journal of Family Psychology, 21, 572–583. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.21.4.572.

Gagnon, J. H., & Simon, W. (1973). Sexual conduct: The social sources of human sexuality. Chicago: Aldine.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 491–512. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.70.3.491.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56, 109–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.56.2.109.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2011). Ambivalent sexism revisited. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35, 530–535. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684311414832.

Glick, P., Fiske, S. T., Mladinic, A., Saiz, J., Abrams, D., Masser, B., … Lopez, W. L. (2000). Beyond prejudice as simple antipathy: Hostile and benevolent sexism across cultures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 763–775. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.763.

Glick, P., Lameiras, M., Fiske, S. T., Eckes, T., Masser, B., Volpato, C., … Wells, R. (2004). Bad but bold: Ambivalent attitudes toward men predict gender inequality in 16 nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 86, 713–728. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.86.5.713.

Gottschall, J., Allison, E., De Rosa, J., & Klockeman, K. (2006). Can literary study be scientific? Results of an empirical search for the virgin/whore dichotomy. Interdisciplinary Literary Studies, 7, 1–17.

Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: Making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549–576. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085530.

Greene, K., & Faulkner, S. L. (2005). Gender, belief in the sexual double standard, and sexual talk in heterosexual dating relationships. Sex Roles, 53, 239–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-5682-6.

Hammond, M. D., & Overall, N. C. (2013). Men's hostile sexism and biased perceptions of intimate partners: Fostering dissatisfaction and negative behavior in close relationships. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 1585–1599. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213499026.

Hanisch, C. (1969). The personal is political. Retrieved from http://www.carolhanisch.org/CHwritings/PIP.html.

Hartmann, U. (2009). Sigmund Freud and his impact on our understanding of male sexual dysfunction. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 6, 2332–2339. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01332.x.

Haxell, N. A. (2000). "Ces dames du cirque": A taxonomy of male desire in nineteenth-century French literature and art. MLN, 115, 783–800. Retrieved from https://muse.jhu.edu/article/22644/summary. Accessed 5 Sep 2016.

Heiman, J. R., Long, J. S., Smith, S. N., Fisher, W. A., Sand, M. S., & Rosen, R. C. (2011). Sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife and older couples in five countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40, 741–753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9703-3.

Hoffman, I. Z. (2009). Doublethinking our way to "scientific" legitimacy: The desiccation of human experience. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 57, 1043–1069. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065109343925.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118.

Infanger, M., Rudman, L. A., & Sczesny, S. (2014). Sex as a source of power? Backlash against self-sexualizing women. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430214558312.

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2003). Rising tide: Gender equality and cultural change around the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511550362.

Jackman, M. R. (1994). The velvet glove: Paternalism and conflict in gender, class, and race relations. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Jeffreys, S. (2005). Beauty and misogyny: Harmful cultural practices in the west. London: Routledge.

Jones, S. L., & Hostler, H. R. (2002). Sexual script theory: An integrative exploration of the possibilities and limits of sexual self-definition. Journal of Psychology and Theology, 30, 120–130.

Josephs, L. (2006). The impulse to infidelity and oedipal splitting. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, 87, 423–437. https://doi.org/10.1516/5A5V-WLPB-4HJ3-329J.

Jost, J. T., & Kay, A. C. (2005). Exposure to benevolent sexism and complementary gender stereotypes: Consequences for specific and diffuse forms of system justification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 498–509. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.498.

Jost, J. T., Kivetz, Y., Rubini, M., Guermandi, G., & Mosso, C. (2005). System-justifying functions of complementary regional and ethnic stereotypes: Cross-national evidence. Social Justice Research, 18, 305–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11211-005-6827-z.

Kane, E. W., & Schippers, M. (1996). Men's and women's beliefs about gender and sexuality. Gender and Society, 10, 650–665. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124396010005009.

Kaplan, H. S. (1988). Intimacy disorders and sexual panic states. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 14, 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926238808403902.

Kay, A. C., & Jost, J. T. (2003). Complementary justice: Effects of "poor but happy" and "poor but honest" stereotype exemplars on system justification and implicit activation of the justice motive. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 823–837. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.85.5.823.

Kravetz, S., Drory, Y., & Shaked, A. (1999). The Israeli Sexual Behavior Inventory (ISBI): Scale construction and preliminary validation. Sexuality and Disability, 17, 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021420300693.

Laumann, E. O., Paik, A., Glasser, D. B., Kang, J. H., Wang, T., Levinson, B., … Gingell, C. (2006). A cross-national study of subjective sexual well-being among older women and men: Findings from the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 35, 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-005-9005-3.

Lawrance, K., & Byers, E. S. (1998). Interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction questionnaire. In C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, R. Baureman, G. Schreer, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Sexuality related measures: A compendium (2nd ed., pp. 514–519). Thousand Oaks: Gage.

Levin, S., & Sidanius, J. (1999). Social dominance and social identity in the United States and Israel: Ingroup favoritism or outgroup derogation? Political Psychology, 20, 99–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/0162-895X.00138.

Little, R. J. (1988). A test of missing completely at random for multivariate data with missing values. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1198–1202. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.1988.10478722.

Macdonald, M. (1995). Representing women: Myths of femininity in the popular media. New York: St. Martin's Press Inc..

MacKinnon, C. A. (1987). Feminism unmodified: Discourses on life and law. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

McClelland, G. H. (2002). Nasty data: Unruly, ill-mannered observations can ruin your analysis. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 393–411). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Moor, A. (2010). She dresses to attract, he perceives seduction: A gender gap in attribution of intent to women's revealing style of dress and its relation to blaming the victims of sexual violence. Journal of International Women's Studies, 11, 115–127.

Muehlenhard, C. L., & McCoy, M. L. (1991). Double standard/double bind: The sexual double-standard and women's communication about sex. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 15, 447–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1991.tb00420.x.

Munford, R. (2007). Wake up and smell the lipgloss. In S. Gillis, G. Howie, & R. Munford (Eds.), Third wave feminism (pp. 266–279). London: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230593664_20.

Nussbaum, M. C. (1999). Sex and social justice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Papp, L. M., Danielewicz, J., & Cayemberg, C. (2012). "Are we Facebook official?" implications of dating partners' Facebook use and profiles for intimate relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 15, 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2011.0291.

Passini, S., & Morselli, D. (2016). Blatant domination and subtle exclusion: The mediation of moral inclusion on the relationship between social dominance orientation and prejudice. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 182–186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.022.

Paul, J. (2013). Madonna and whore: The many faces of Penelope in Camerini's Ulysses. In K. P. Nikoloutsos (Ed.), Ancient Greek women in film (pp. 139–162). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199678921.003.0007.

Pomeroy, S. B. (1975). Goddesses, whores, wives, and slaves: Women in classical antiquity. New York: Schocken.

Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable relevant to social roles and intergroup relations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741–763. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741.

Quintana, S. M., & Maxwell, S. E. (1999). Implications of recent developments in structural equation modeling for counseling psychology. The Counseling Psychologist, 27, 485–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000099274002.

Reiss, I. L. (1960). Premarital sexual standards in America. New York: The Free Press.

Reiss, I. L. (1964). The scaling of premarital sexual permissiveness. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 26, 188–198. https://doi.org/10.2307/349726.

Rollero, C., Glick, P., & Tartaglia, S. (2014). Psychometric properties of short versions of the Ambivalent Sexism Inventory and Ambivalence Toward Men Inventory. TPM: Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology, 21, 149–159.

Rubin, G. (1975). The traffic in women: Notes on the "political economy" of sex. In E. Lewin (Ed.), Feminist anthropology: A reader (pp. 87–106). New York: Monthly Review Press.

Rudman, L. A., & Borgida, E. (1995). The afterglow of construct accessibility: The behavioral consequences of priming men to view women as sexual objects. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 31, 493–517. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.1995.1022.

Rudman, L. A., & Phelan, J. E. (2007). The interpersonal power of feminism: Is feminism good for romantic relationships? Sex Roles, 57, 787–799. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9319-9.

Rudman, L. A., Moss-Racusin, C. A., Phelan, J. E., & Nauts, S. (2012). Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48, 165–179. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2011.10.008.

Rudman, L. A., Fetterolf, J. C., & Sanchez, D. T. (2013). What motivates the sexual double standard? More support for male versus female control theory. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167212472375.

Rust, J., & Golombok, S. (1985). The Golombok-Rust Inventory of Sexual Satisfaction (GRISS). British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24, 63–64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1985.tb01314.x.

Sanchez, D. T., Crocker, J., & Boike, K. R. (2005). Doing gender in the bedroom: Investing in gender norms and the sexual experience. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 31, 1445–1455. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205277333.

Schafer, J. L., & Graham, J. W. (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7, 147–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147.

Segal, L. (2007). Slow motion: Changing masculinities, changing men (3rd ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230582521.

Sev'er, A., & Yurdakul, G. (2001). Culture of honor, culture of change: A feminist analysis of honor killings in rural Turkey. Violence Against Women, 7, 964–998. https://doi.org/10.1177/10778010122182866.

Sharoni, S. (1992). Every woman is an occupied territory: The politics of militarism and sexism and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Journal of Gender Studies, 1, 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.1992.9960512.

Shnabel, N., Bar-Anan, Y., Kende, A., Bareket, O., & Lazar, Y. (2016a). Help to perpetuate traditional gender roles: Benevolent sexism increases engagement in dependency-oriented cross-gender helping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110, 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000037.

Shnabel, N., Dovidio, J. F., & Levin, Z. (2016b). But it's my right! Framing effects on support for empowering policies. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 63, 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.11.007.

Shook, N. J., Hopkins, P. D., & Koech, J. M. (2016). The effect of intergroup contact on secondary group attitudes and social dominance orientation. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 19, 328–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430215572266.

Sibley, C. G., & Wilson, M. S. (2004). Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexist attitudes toward positive and negative sexual female subtypes. Sex Roles, 51, 687–696. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-004-0718-x.

Sibley, C. G., Wilson, M. S., & Duckitt, J. (2007). Antecedents of men's hostile and benevolent sexism: The dual roles of social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 33, 160–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206294745.

Silverstein, J. L. (1998). Countertransference in marital therapy for infidelity. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 24, 293–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926239808403964.

Simon, W., & Gagnon, J. J. (1986). Sexual scripts: Permanence and change. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 15, 97–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01542219.

Sprecher, S. (2002). Sexual satisfaction in premarital relationships: Associations with satisfaction, love, commitment, and stability. Journal of Sex Research, 39, 190–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490209552141.

Sprecher, S. (2011). Premarital Sexual Permissiveness Scale. In T. D. Fisher, C. M. Davis, W. L. Yarber, & S. L. Davis (Eds.), Handbook of sexuality-related measures (3rd ed., pp. 511–512). New York: Routledge.

Sprecher, S. (2013). Attachment style and sexual permissiveness: The moderating role of gender. Personality and Individual Differences, 55, 428–432. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.04.005.

Sprecher, S., & Cate, R. M. (2004). Sexual satisfaction and sexual expression as predictors of relationship satisfaction and stability. In J. H. Harvey, A. Wenzel, & S. Sprecher (Eds.), The handbook of sexuality in close relationships (pp. 235–256). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sprecher, S., & Hatfield, E. (1996). Premarital sexual standards among US college students: Comparison with Russian and Japanese students. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 25, 261–288. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02438165.

Sprecher, S., McKinney, K., Walsh, R., & Anderson, C. (1988). A revision of the Reiss premarital sexual permissiveness scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 50, 821–828. https://doi.org/10.2307/352650.

Stevens, E. P. (1973). Marianismo: The other face of machismo in Latin America. In A. Pescatello (Ed.), Female and male in Latin America (pp. 89–101). Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Symons, D. (1979). The evolution of human sexuality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (5th ed.). New York: Pearson.

Tanenbaum, L. (2000). Slut!: Growing up female with a bad reputation. New York: Harper Collins.

Tanzer, D. (1985). Real men don't eat strong women: The virgin-Madonna-whore complex updated. The Journal of Psychohistory, 12, 487–495.

Tavris, C., & Wade, C. (1984). The longest war: Sex differences in perspective. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Taylor, L. D. (2005). Effects of visual and verbal sexual television content and perceived realism on attitudes and beliefs. Journal of Sex Research, 42, 130–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490509552266.

Tolman, D. L., & Tolman, D. L. (2009). Dilemmas of desire: Teenage girls talk about sexuality. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Travis, C. B., & White, J. W. (Eds.). (2000). Sexuality, society, and feminism. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10345-000.

Tropp, L. (2006). “Faking a sonogram”: Representations of motherhood on Sex and the City. The Journal of Popular Culture, 39, 861–877. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5931.2006.00309.x.

United Nations Development Programme. (2016). Human Development Report 2016. Retrieved from http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/HDR2016_EN_Overview_Web.pdf. Accessed 6 Jun 2017.

Vaillancourt, T., & Sharma, A. (2011). Intolerance of sexy peers: Intrasexual competition among women. Aggressive Behavior, 37, 569–577. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20413.

Vandello, J. A., Bosson, J. K., Cohen, D., Burnaford, R. M., & Weaver, J. R. (2008). Precarious manhood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 1325–1339. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012453.

Welldon, E. V. (1992). Mother, Madonna, whore: The idealization and denigration of motherhood. London, UK: Karnac Books.

Welles, C. E. (2005). Breaking the silence surrounding female adolescent sexual desire. Women & Therapy, 28, 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1300/J015v28n02_03.

Weston, R., & Gore, P. A., Jr. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist, 34, 719–751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286345.

Winter, D. D. N. (2002). (En)gendering sustainable development. In P. Schmuck & W. P. Schultz (Eds.), Psychology of sustainable development (pp. 79–95). Norwell: Kluwer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-0995-0_5.

Wolf, N. (1997). Promiscuities: The secret struggle for womanhood. New York: Random House.

Wright, R. (2010). The moral animal: Why we are, the way we are: The new science of evolutionary psychology. New York: Knopf.

Wright, P. J., & Tokunaga, R. S. (2013). Activating the centerfold syndrome: Recency of exposure, sexual explicitness, past exposure to objectifying media. Communication Research, 42, 864–897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650213509668.

Young, C. (1993). New Madonna/whore syndrome: Feminism, sexuality, and sexual harassment. New York Law School Law Review, 38, 257–288.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The research was conducted in compliance with APA’s ethical standards in the treatment of human participants, which includes providing informed consent and a full debriefing. The study was approved by Tel-Aviv University Institutional Review Board.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Electronic supplementary material

ESM 1

(DOCX 73 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bareket, O., Kahalon, R., Shnabel, N. et al. The Madonna-Whore Dichotomy: Men Who Perceive Women's Nurturance and Sexuality as Mutually Exclusive Endorse Patriarchy and Show Lower Relationship Satisfaction. Sex Roles 79, 519–532 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0895-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-018-0895-7