Abstract

Purpose

Known association between tinnitus and psychological distress prompted us to examine patients with chronic tinnitus by using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI), which is a standardized and reliable method used for the diagnosis of mental disorders.

Methods

One hundred patients with chronic tinnitus admitted to the Tinnitus Center, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, were included in this study. Data were collected between February 2008 and February 2009. Besides CIDI, the Tinnitus Questionnaire according to Goebel and Hiller, the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale, and the General Anxiety Disorder—7 were used.

Results

Using CIDI, we have identified one or more mental disorders in 46 tinnitus patients. In that group, we found persistent affective disorders (37 %), anxiety disorders (32 %), and somatoform disorders (27 %). Those patients who had affective or anxiety disorders were more distressed by tinnitus and were more anxious and more depressed than tinnitus patients without mental disorders. Psychological impairment positively correlated with tinnitus distress: Patients with decompensated tinnitus had significantly more affective and anxiety disorders than patients with compensated tinnitus.

Conclusions

In the present study, we have detected a high rate (almost half of the cases) of psychological disorders occurring in patients with chronic tinnitus. The patients diagnosed with psychological disorders were predominantly affected by affective and anxiety disorders. Psychological disorders were associated with severity of tinnitus distress. Our findings imply a need for routine comprehensive screening of mental disorders in patients with chronic tinnitus.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Tinnitus is a phantom sound which can be perceived in one or both ears. There are subjective and objective forms of tinnitus. Objective tinnitus is very rare and can be caused by sounds in the body such as muscle contractions or blood flow [1]. Most patients suffer from a subjective tinnitus which can be a result of inappropriate stimulation of auditory pathways by a variety of pathological conditions. More than 90 % of tinnitus patients have a cochlear hearing loss or a hearing loss at frequencies above 8 kHz [2, 3]. Tinnitus frequency is usually detectable in the frequencies of greatest hearing loss [4]. In addition to hearing loss, also orthopedic illnesses, infections, and use of certain drugs can be a cause of tinnitus [5].

Epidemiological studies have demonstrated that approximately 35 % of the population experience tinnitus over their lifetime, 15 % of the adults has chronic tinnitus, whereas 0.5 % feel severely affected by tinnitus [6–8].

Regardless of origin and location of tinnitus, the subjective distress caused by tinnitus is not as much attributed to the tinnitus frequency and intensity, but more to coexisting mental disorders [9–11]. A decompensation of tinnitus seems to have an enormous impact on emotional well-being, as it is often accompanied by restricted quality of life [12]. Moreover, psychological symptoms were reported by 93 % of patients highly distressed by tinnitus [13]. Mental disorders reported to be frequently associated with tinnitus include depression, dysthymia, insomnia and lack of concentration, somatoform disorders, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive disorder [11, 12, 14, 15]. The remaining question is whether the coexistence of mental disorder with tinnitus could be a predictor for the severity of tinnitus-related distress. A number of clinical researchers agree that patients with long-term somatoform and depressive disorders are more sensitive to noise than patients with no mental history [13, 16–19].

In recent years, there was increased interest in using standardized methods to reliably diagnose psychiatric disorders. The involvement of mental disorder not only requires specialized diagnosis but also specialized interdisciplinary therapy. Evidently, proper diagnosis process will increase the therapeutic effectiveness of tinnitus treatment. Psychological questionnaires are commonly used as screening instruments for psychological disorders; however, they do not allow diagnosing mental and behavioral disorders according to the International Classification of Diseases—10 (ICD-10). When compared with other psychological questionnaires, the benefit of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) is making specific and multiple diagnoses and covering all psychological disorders mentioned in the ICD-10 and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders—IV (DSM-IV). Spectrum of the diagnoses covered by CIDI ranges from the organically related mental disorders, substance-related disorders such as alcohol abuse, psychotic disorders, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, dissociative disorders, and somatoform disorders to the eating disorders. Since its first appearance in 1990, CIDI was used in over 1000 various scientific studies and proved to have very good psychometric properties [20].

The aim of our study was to determine the rate of mental disorders in tinnitus patients using the CIDI. Moreover, we wanted to compare the results obtained by CIDI with the results obtained by other psychometric questionnaires.

Methods

One hundred patients were included in this study. All patients were admitted to a day ward of the Tinnitus Center, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, for a 7-day extended multimodal tinnitus retraining therapy. The study was conducted between February 2008 and February 2009. The patients answered questions about tinnitus distress, anxiety, and depression before the beginning of the treatment. CIDI was performed at the same time.

There were no exclusion criteria. All patients had tinnitus for at least 3 months. All patients have read and signed written consent form. The study was approved by a local ethics committee.

Audiometry and tinnitus matching

Determination of hearing thresholds was done with the help of pure-tone audiometry at frequencies of 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 kHz. Hearing loss was classified as normal hearing (0–20 dB hearing loss), mild hearing loss (21–40 dB), and moderate-to-severe hearing loss (>40 dB) [21]. To determine the frequency of tinnitus, patients were exposed to a narrow-band noise or pure tones 10 dB above the hearing threshold in the affected ear via headphones. Based on the patients’ reports, tinnitus frequency and tinnitus loudness in dB hearing level (dB HL) and dB sensation level (dB SL) were then determined.

Psychometric diagnosis

In order to assess mental disorders such as anxiety, depression, and mood disorders, the CIDI was performed. Moreover, all patients filled psychological questionnaires specified below to measure tinnitus and psychological distress.

Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI)

The CIDI was originally developed by the World Health Organization and the United States Alcohol, Drug Abuse and Mental Health Administration [22]. In this work, the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview was used. This diagnostic test is used for the detection of mental disorders according to the criteria of ICD-10 and DSM-IV [23, 24]. We used CIDI 3.0 version as a Computer-Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI V21.1.3) provided by the WHO [25]. CAPI V21.1.3 is compatible with DOS 3.1 and all subsequent Microsoft operating systems [26]. CIDI combines interview strategies consistent with diagnostic screening questionnaires. The application of the CIDI is suitable for routine clinical diagnostics, in which psychological disorders are identified, for defining temporal relations and for the exclusion diagnostics [22, 27]. However, no personality disorders are detected. The CIDI is fully structured and can be completed by a patient with help of clinicians or trained non-clinical personnel in about 45–90 min. The CIDI uses multiple-choice questions, for example “how much did your symptom(s) ever interfere with your life or activities—a lot, a little, or not at all?” [28]. After performing the computerized CIDI, psychological diagnoses according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV are automatically generated. CIDI detects psychiatric disorders and is a reliable tool for almost all DSM-IV symptom questions (r = 0.72) [20]. The interrater reliability of diagnostic decisions is very high and has kappa values between 0.82 and 0.98 [29, 30]. Comparison between diagnoses made with the use of CIDI and clinical diagnoses in the same patients showed good diagnostic compatibility (κ = 0.77) [22, 27]. The test validity had satisfactory kappa values of 0.39 for psychotic disorders and 0.82 for panic disorder [29].

Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ)

The Tinnitus Questionnaire (TQ) according to Goebel and Hiller measures the subjective strain by tinnitus [31]. The overall result can determine the strain to be light (up to 30 points), medium (31–46 points), strong (47–59 points), or very strong (60–84 points). Additionally, the patients can be divided into suffering from chronic compensated tinnitus (≤46 points) and chronic decompensated tinnitus (47–84 points). It also offers the following subscales, categorizing symptoms that may accompany or follow tinnitus: emotional distress, cognitive distress, intrusiveness, sleep disturbances, hearing problems, and somatic complaints. Additionally, the subscales emotional distress and cognitive distress are added to psychological distress. The test–retest reliability is 0.94 for the TQ total score and between 0.86 and 0.92 for the subscales. The Cronbach’s α is 0.94 for the TQ score and in the range of 0.74–0.92 for the subscales [32].

Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS)

The Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) was developed in 1983 by Zigmond and Snaith [33] and is used to measure anxiety and depression [34]. The HADS includes 14 items; of which 7 each are associated with anxiety and depression subscales. HADS records generalized anxiety symptoms but not the situational anxiety disorders. In this way, score fluctuation caused by fear of medical treatment can be avoided [34]. Only one, medium to longer-term change in generalized anxiety can be identified. The total score value is divided into the following severity levels in the two scales anxiety and depression (maximum score of each scale is 21 points): normal (0–7 points), borderline (8–10 points), striking (11–21 points). A series of studies have demonstrated good validity and reliability of HADS [34–37].

General Anxiety Disorder—7 (GAD-7)

General Anxiety Disorder—7 (GAD-7) belongs to the family of the Patient Health Questionnaire instruments and is used for the diagnosis of generalized anxiety and for measuring the severity and course of anxiety [38]. A cumulative score value of all 7 items is used to assess the severity of anxiety. Four levels of severity are distinguished: minimal (0–4 points), low (5–9 points), moderate (10–14 points), and severe (15–21 points). The German version of questionnaire was tested repeatedly for validity and reliability and revealed good internal consistency (r (α) = 0.89) [39]. Therefore, we included the GAD-7 in our study as an efficient method for screening of generalized anxiety disorder [40] and depression [34].

Statistical analysis

Two groups of patients were compared by the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U test. The psychometric scores were compared between the three groups of hearing loss and between the four groups of professional status using the nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA with hearing loss or profession as grouping variables. Multiple comparisons of mean ranks served as post hoc test. Spearman’s correlation was used to test the relation between psychometric test scores and hearing loss or age as well as between different psychometric test scores. Frequency distributions were compared using Pearson’s χ 2 test. p < 0.05 was chosen as the level of significance (Statistica 7.1, StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA).

Results

Fifty-five women and 45 men participated in the study. The average age at admission was 49.6 (SD = 13.7) and did not differ between women and men (Mann–Whitney U test). Most of the patients (54) were employed, 22 patients were retired, 12 were unemployed, and 9 were students or undergoing occupational retraining. Three patients did not provide the information regarding their profession.

Tinnitus parameters, hearing loss, and psychometrically recorded tinnitus annoyance, depression, and anxiety

At the time of the study, 62 patients had double-sided and 38 patients had one-sided tinnitus. The average tinnitus frequency was 5.3 kHz (SD = 2.6, range 0.1–9). The average tinnitus loudness was 37.9 dB HL (SD = 22.6, range 0–102) and 4.8 dB SL (SD = 4.8, range 0–20). The hearing loss (mean pure-tone threshold) was 23.9 dB (SD = 14.8, range 2.5–73 dB).

No linear correlations were found between the audiometric parameters and psychometric scores, except for the hearing loss and TQ subscale “hearing problems” (r = 0.52, p < 0.0001, Spearman’s correlation). Therefore, we analyzed the scores within three categories of hearing loss (Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA and multiple comparisons of mean ranks). Only 13 % of patients had normal hearing with a one- or double-sided hearing loss of 0–20 dB, 26 % of patients had a mild hearing loss (21–40 dB) and most patients (61 %) had moderate-to-severe hearing loss (>40 dB). The psychometric scores obtained from these three groups did not differ in terms of tinnitus-related distress measured by the TQ total score or its subscales except for the subscale “hearing problems” (Table 1). Patients with a hearing loss of >40 dB scored higher in the TQ subscale “hearing problems” than patients with lower hearing loss (20–40 dB) or normal hearing (≤20 dB hearing loss). Anxiety and depression scores measured by the HADS and GAD-7 did not differ between the patient groups with different hearing abilities either.

Eighty patients (80 %; 43 women and 37 men) had a compensated tinnitus (TQ total score <47) and 20 patients (20 %; 12 women and 8 men) decompensated tinnitus (TQ total score ≥47). The values of the TQ total score and the TQ subscales of patients with compensated and decompensated tinnitus as well as of all 100 patients are shown in Table 2.

The mean scores of the HADS were 5.1 (SD = 3.3) and 7.8 (SD = 3.95) for depression and anxiety, respectively. The mean total score of the GAD-7 was 6.9 (SD = 4.5).

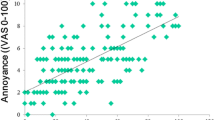

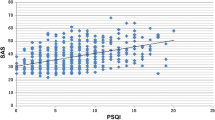

Patients with decompensated tinnitus had significantly higher values for the HADS depression score, HADS anxiety score, and GAD-7 total score as compared to patients with compensated tinnitus (Mann–Whitney U test). The mean ranks of patients with decompensated and compensated tinnitus were as follows: 64.2 and 47.1 (p = 0.018) for the HADS depression score; 64.1 and 47.1 (p = 0.019) for the HADS anxiety score; and 70.9 and 45.4 (p = 0.0001) for the GAD-7 total score. Additionally, we found significant correlations between tinnitus-related distress and anxiety and depression measured by the HADS and GAD-7 (Spearman’s correlation). The higher the tinnitus annoyance, the higher the HADS depression score (r = 0.32; p = 0.001) the HADS anxiety score (r = 0.42; p = 0.000) and the GAD-7 Score (r = 0.44; p = 0.000), reported by the patients.

There were no significant differences between women and men (Mann–Whitney U test).

In addition, we analyzed the influence of patients’ age on the parameters measured (Spearman’s correlation). There was a correlation between age and hearing loss (r = 0.59, p < 0.0001); however, no correlations were found between age and psychometric scores.

There were no differences in psychometric scores between the four categories of professional status: employment, retirement, unemployment, or occupational retraining/education (Kruskal–Wallis ANOVA).

Diagnosis of mental disorders using CIDI

Mental disorders were analyzed with the use of CIDI; each of the disorders was identified according to ICD-10. Forty-six of 100 tinnitus patients included in this study were positively diagnosed with one or more mental conditions. One mental disorder was diagnosed in 24 patients; two to six mental disorders were diagnosed in 22 patients. Affective disorders (37 %) and anxiety disorders (32 %) were most predominant in these 46 patients, followed by somatoform disorders (27 %) as demonstrated in Fig. 1. Mental disorders were grouped for clarity as follows: Depressive episodes and recurrent depressive disorders were combined to the group of affective disorders, whereas phobic disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and other anxiety disorders were classified as anxiety disorders.

There were no differences in the frequency distribution of mental disorders between the three groups of hearing loss, between women and men, and between the four groups of professional status (Pearson’s χ 2 test).

Patients with decompensated tinnitus suffered significantly more often from affective and anxiety disorders than patients with compensated tinnitus (Pearson’s χ 2 test) as shown in Table 3.

Relationship between CIDI diagnoses and psychometric questionnaires

The affective, anxiety, and somatoform disorders were closely examined, as these were most frequently diagnosed in our sample and because other studies postulated close correlation of these disorders and tinnitus [10, 13, 17, 41–44].

Tinnitus patients who were diagnosed with an affective disorder using CIDI had higher TQ total scores and had more pronounced emotional, cognitive and psychological distress, higher intrusiveness of tinnitus and more sleep disturbances, and somatic complaints than patients without affective disorder (Table 4). In addition, patients with CIDI-diagnosed affective disorder reported more anxiety and depression than tinnitus patients without affective disorder, as per HADS and GAD-7.

Tinnitus patients with anxiety disorders had significantly higher TQ total scores and higher scores in all TQ subscales than patients without anxiety disorders (Table 5). In addition, patients with anxiety disorders had higher HADS anxiety scores and GAD-7 total scores than patients without anxiety disorders.

No differences were found between tinnitus patients with and without somatoform disorders in terms of tinnitus annoyance (TQ) or anxiety and depression (HADS) (Table 6). However, patients with somatoform disorders had significantly higher GAD-7 scores than patients without somatoform disorders.

Additionally, we compared the tinnitus-related distress of patients with more than one psychological problem (n = 22) and with only one psychological problem (n = 24), as per CIDI. Patients with more than one mental disorder had significantly higher TQ total scores (mean = 46.8, mean rank = 30.0) than patients with only one mental disorder (mean = 31.3, mean rank = 18.0) (p = 0.003, Mann–Whitney U test).

Discussion

Based on our study, we can conclude the following:

(1) The incidence rate of psychiatric disorder in our sample was 46 %, as per CIDI diagnosis. (2) The most common conditions diagnosed with CIDI in tinnitus patients were affective and anxiety disorders. Patients with decompensated tinnitus were more frequently affected by affective or anxiety disorders than the patients with compensated tinnitus. (3) The grade of tinnitus annoyance (TQ) associated with the depression and anxiety scores found with other psychometric instruments.

Almost all patients in our sample had unilateral or bilateral hearing loss (87 %). Other studies have also demonstrated high prevalence of hearing loss in tinnitus patients, reaching up to 95 % [45, 46]. Most of the patients in our sample had a high-frequency hearing loss. This is of particular importance from the therapeutic point of view and implies that tinnitus patients should be fitted with hearing aids to improve communication and hearing. Using hearing aid can lead to at least partial tinnitus masking and may improve habituation of tinnitus. In our recent study, we demonstrated that patients with decompensated tinnitus have more pronounced hearing loss than patients with compensated tinnitus [47]. In the present study, scores in TQ subscale “hearing problems” reflected the grade of hearing loss, whereas the TQ total score and the subscale “somatic complaints” tended to increase with hearing loss, corroborating our previous work.

Diagnosis of mental disorders by CIDI and psychometric questionnaires

In our study, the incidence rate of mental disorders (46 %) was slightly lower as compared to the results of other studies. Other groups have diagnosed mental disorders in 53–63 % of tinnitus patients [43, 48, 49]. The low rate of psychological disorders found in our sample could be attributed to the fact that our facility is ORL/ENT-oriented in contrast to more psychology-oriented facilities of others [43, 50]. The frequencies of mental disorders detected by CIDI in tinnitus patients reported by other groups are summarized in Table 7.

Detection of psychological disorders by CIDI and psychometric questionnaires: patients with compensated versus decompensated tinnitus

Twenty percent of our sample had decompensated tinnitus, which is a standard distribution found among patients undergoing treatment in our day clinic. Highly distressed patients are usually admitted to a stationary unit. The classification “compensated/decompensated” is made based on the TQ, typically used in German-speaking countries. More patients with compensated tinnitus are treated in an outpatient (62 %) [44] than in an inpatient setting (38 % of patients) [51].

According to CIDI, patients with decompensated tinnitus were more frequently diagnosed with affective or anxiety disorders than the patients with compensated tinnitus. Our results agree with other studies, which demonstrated that 30–85 % patients with chronic decompensated tinnitus are affected by common mood disorders [14] and 30–60 % of chronic decompensated tinnitus patients has common anxiety disorders [14]. In contrast, there were no significant differences between patients with decompensated and compensated tinnitus in terms of incidence of somatoform disorders. One explanation for this discrepancy may lie in the fact that CIDI does not adequately cover somatoform disorders, therefore could lead to false-negative diagnosis. The drawback of our study is that we have not used additional questionnaires for the specific assessment of somatoform disorders in order to verify this explanation.

In addition, patients with decompensated tinnitus scored higher for anxiety and depression than patients with compensated tinnitus, when using the psychological questionnaires. This is consistent with findings published by others [44, 52, 53] and strongly implicates need for psychological screening of all patients with decompensated tinnitus.

Taken together, we found that patients diagnosed by CIDI with anxiety or affective disorders have a higher burden of anxiety or depression revealed by psychometric questionnaires, confirming the agreement between these two types of diagnostic instruments.

Although there was no correlation between tinnitus severity and incidence of somatoform disorders, 30 % of the patients with decompensated tinnitus and 21 % of the patients with compensated tinnitus were diagnosed with a somatoform disorder. The advantage of the CIDI is that it examines the whole spectrum of psychological disorders according to ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria, whereas the other questionnaires concentrate each on a specific disorder. In addition, CIDI provides a differential diagnosis and identification of a precise disorder, for example panic disorder, agoraphobia. The advantage of personnel-assisted interview is that when patients are uncertain about the meaning of a question, the personnel is there to help.

Tinnitus and affective or anxiety disorder (CIDI)

In our sample, the prevalence of affective disorders (37 %) detected in 46 of our patients using CIDI, corresponds to this found in some studies [16, 43]. However, there are other studies that report much higher rates of affective disorders in tinnitus patients, reaching up to 69 % [41, 49]. In our patient population, we detected anxiety disorders with a prevalence rate of 32 %. This is less frequent than the prevalence of 60–67 %, reported in other studies [41, 42]. Again, ORL/ENT orientation of our unit may possibly induce a bias in our sample, similar to the, but different in consequences, bias in sample assessed by more psychology-oriented tinnitus facilities. Nevertheless, affective and anxiety disorders were the most common mental disorder found in our patients. This can be explained by the fact that tinnitus distress associates with a reduction in quality of life (possibly associated with impairments in social relationships), which in turn can lead to secondary anxiety, depression, or dysthymia. It could also be possible that a pre-existing mood disorder could lead to an increased perception of tinnitus, as it is known in other somatic complaints [54]. In addition, patients with anxiety disorders seek medical help more frequently than other patients and consequently more frequently join clinical therapy groups or clinical studies.

Patients who were diagnosed by CIDI with affective or anxiety disorder had significantly higher tinnitus-related distress (TQ) than patients free of psychological disorder. It is plausible that an additional symptom brings additional distress, which may in turn adversely affect the processing of tinnitus. Other groups have also demonstrated significant association between tinnitus distress and anxiety disorders [18, 55].

Tinnitus and somatoform disorder (CIDI)

In our study, the frequency rate of somatoform disorders diagnosed by CIDI was 27 %. Other studies reported higher incidence of somatoform disorders in tinnitus [43, 56]. The association between tinnitus and somatoform disorders was discussed by Hiller [17] who postulated that tinnitus may be a part of somatoform disorder. This hypothesis was based on an observation that patients with somatoform disorders frequently report tinnitus [17]. In addition, the symptoms of somatoform disorders share similarities with anxiety disorders. Unfortunately, there are no specific exclusion criteria according to ICD-10 to discriminate between anxiety and somatoform disorders. The somatoform disorders may possibly coexist with anxiety disorders [17], but to date, little is known about this topic.

In our investigation, patients who were diagnosed by CIDI with a somatoform disorder had no increased tinnitus distress as per TQ when compared with the patients without a somatoform disorder. These results suggest either that the patients with somatoform disorders do not have increased tinnitus distress or that the somatoform disorders are inadequately detected by CIDI.

Assessment of CIDIs

Despite the frequently reported association of tinnitus and mental disorder, there are only a few studies using CIDI in tinnitus diagnostics (see Table 7). Here, we have used the CIDI for the mental diagnosis of tinnitus patients and compared the outcome with that obtained using various psychometric methods. We found that those tinnitus patients who were diagnosed by CIDI with a psychological disorder had also high depression (HADS) and anxiety scores (GAD-7, HADS) implying good correlation between the two types of diagnostic instruments. Our results also suggest that CIDI detects both affective and anxiety disorders in tinnitus patients. Moreover, we found that patients with somatoform disorders had higher anxiety GAD-7 scores than patients without somatoform disorders. In agreement with this, other authors reported too a high prevalence of anxiety disorders in patients with somatoform disorders [57].

Our data have demonstrated a strong association between the severity of tinnitus and mental disorders, however; further studies are needed to examine whether tinnitus leads to mental distress or vice versa.

Based on relatively high rate of mental conditions detected in our present study, we conclude that screening for mental disorders by CIDI could be incorporated into routine tinnitus diagnostics. This is particularly true for tinnitus patients with elevated psychometric and TQ scores. Affective and anxiety disorders lower the quality of life [58] and thus likely increase the tinnitus annoyance, slowing down the recovery process and therefore should be detected and adequately treated. In patients with severe tinnitus and psychological disorders such as depression or anxiety disorders, psychopharmacological drugs like sertraline, paroxetine, and nortriptyline can be considered, as they can reduce the tinnitus annoyance and psychopathological symptoms [59].

Abbreviations

- CAPI:

-

Computer-Assisted Personal Interview

- CIDI:

-

Composite International Diagnostic Interview

- DSM IV:

-

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-IV

- GAD-7:

-

General Anxiety Disorder—7

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale

- ICD-10:

-

International Classification of Diseases—10

- TQ:

-

Tinnitus Questionnaire

References

Schleuning, A. J. (1991). Management of the patient with tinnitus. Medical Clinics of North America, 75(6), 1225–1237.

Sindhusake, D., Golding, M., Newall, P., Rubin, G., Jakobsen, K., & Mitchell, P. (2003). Risk factors for tinnitus in a population of older adults: The blue mountains hearing study. Ear and Hearing, 24(6), 501–507.

Roberts, L. E., Moffat, G., & Bosnyak, D. J. (2006). Residual inhibition functions in relation to tinnitus spectra and auditory threshold shift. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. Supplement, 556, 27–33.

Jastreboff, P. J., & Hazell, J. W. (1993). A neurophysiological approach to tinnitus: Clinical implications. British Journal of Audiology, 27(1), 7–17.

Henry, J. A., Zaugg, T. L., & Schechter, M. A. (2005). Clinical guide for audiologic tinnitus management I: Assessment. American Journal Audiology, 14(1), 21–48.

Coles, R. R. (1984). Epidemiology of tinnitus: (1) Prevalence. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. Supplement, 9, 7–15.

Meikle, M., & Taylor-Walsh, E. (1984). Characteristics of tinnitus and related observations in over 1800 tinnitus clinic patients. Journal of Laryngology and Otology. Supplement, 9, 17–21.

Pilgramm, M., Rychlik, R., Lebisch, H., Siedentop, H., Goebel, G., & Kirchoff, D. (1999). Tinnitus in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Eine repräsentative epidemiologische Studie. HNO aktuell, 7, 261–265.

Unterrainer, J., Greimel, K. V., Leibetseder, M., & Koller, T. (2003). Experiencing tinnitus: Which factors are important for perceived severity of the symptom? The International Tinnitus Journal, 9(2), 130–133.

Zirke, N., Goebel, G., & Mazurek, B. (2010). Tinnitus and psychological comorbidities. HNO, 58(7), 726–732.

Zirke, N., Seydel, C., Szczepek, A. J., Olze, H., Haupt, H., & Mazurek, B. (2012). Psychological comorbidity in patients with chronic tinnitus: Analysis and comparison with chronic pain, asthma or atopic dermatitis patients. Quality of Life Research. doi:10.1007/s11136-012-0156-0

Härter, M., Maurischat, C., Weske, G., Laszig, R., & Berger, M. (2004). Psychological stress and impaired quality of life in patients with tinnitus. HNO, 52(2), 125–131.

Goebel, G., & Fichter, M. (2005). Psychiatrische Komorbidität bei Tinnitus. HNO Praxis Heute, 25, 137–150.

Goebel, G., & Hiller, W. (1998). Co-morbidity of psychological disturbances in patients with chronic tinnitus. Surrey, UK: Quintessence Publishing.

Hiller, W., & Goebel, G. (1992). A psychometric study of complaints in chronic tinnitus. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 36(4), 337–348.

Hiller, W., & Goebel, G. (1999). Assessing audiological, pathophysiological, and psychological variables in chronic tinnitus: A study of reliability and search for prognostic factors. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 6(4), 312–330.

Hiller, W., Janca, A., & Burke, K. C. (1997). Association between tinnitus and somatoform disorders. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 43(6), 613–624.

Olderog, M., Langenbach, M., Michel, O., Brusis, T., & Kohle, K. (2004). Predictors and mechanisms of tinnitus distress—a longitudinal analysis. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie, 83(1), 5–13.

Svitak, M. (1998). Psychosoziale Aspekte des chronisch dekompensierten Tinnitus. Psychische Komorbidität, Somatisierung, dysfunktionale Gedanken und psychosoziale Beeinträchtigung. Salzburg: Psychologisches Institut.

Wittchen, H. U. (1994). Reliability and validity studies of the WHO–Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI): A critical review. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 28(1), 57–84.

Boenninghaus, G. H., & Lenarz, M. (2005). Hals-Nasen-Ohrenheilkunde. Berlin: Springer.

Janca, A., Robins, L. N., Cottler, L. B., & Early, T. S. (1992). Clinical observation of assessment using the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). An analysis of the CIDI Field Trials–Wave II at the St Louis site. British Journal of Psychiatry, 160, 815–818.

Kessler, R. C., Calabrese, J. R., Farley, P. A., Gruber, M. J., Jewell, M. A., Katon, W., et al. (2012). Composite International Diagnostic Interview screening scales for DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders. Psychological Medicine, 18, 1–13.

Haro, J. M., Arbabzadeh-Bouchez, S., Brugha, T. S., de Girolamo, G., Guyer, M. E., Jin, R., et al. (2006). Concordance of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Version 3.0 (CIDI 3.0) with standardized clinical assessments in the WHO World Mental Health surveys. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 15(4), 167–180.

Komiti, A. A., Jackson, H. J., Judd, F. K., Cockram, A. M., Kyrios, M., Yeatman, R., et al. (2001). A comparison of the Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI-Auto) with clinical assessment in diagnosing mood and anxiety disorders. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 35(2), 224–230.

World Health Organisation. Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). a) CIDI-interview (version 1.0), b) CIDI-user manual, c) CIDI-training manual d) CIDI-computer programs. (1990). Geneva: World Health Organisation.

Janca, A., Robins, L. N., Bucholz, K. K., Early, T. S., & Shayka, J. J. (1992). Comparison of Composite International Diagnostic Interview and clinical DSM-III-R criteria checklist diagnoses. Acta Psychiatrica Scand., 85(6), 440–443.

Robins, L. N., Wing, J., Wittchen, H. U., Helzer, J. E., Babor, T. F., Burke, J., et al. (1988). The Composite International Diagnostic Interview An epidemiologic Instrument suitable for use in conjunction with different diagnostic systems and in different cultures. Archives of General Psychiatry, 45(12), 1069–1077.

Wittchen, H.-U., & Pfister, H. (1997). Instruktionsmanual zur Durchführung von DIA-X-Interviews. Frankfurt: Svets&Zeitlinger B.V.

Wittchen, H. U., Lachner, G., Wunderlich, U., & Pfister, H. (1998). Test-retest reliability of the computerized DSM-IV version of the Munich-Composite International Diagnostic Interview (M-CIDI). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 33(11), 568–578.

Goebel, G., & Hiller, W. (Eds.). (1998). Tinnitus-Fragebogen (TF). Ein Instrument zur Erfassung von Belastung und Schweregrad bei Tinnitus (Manual zum Fragebogen). Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Hiller, W., Goebel, G., & Rief, W. (1994). Reliability of self-rated tinnitus distress and association with psychological symptom patterns. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33(Pt 2), 231–239.

Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scand., 67(6), 361–370.

Stafford, L., Berk, M., & Jackson, H. J. (2007). Validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and Patient Health Questionnaire-9 to screen for depression in patients with coronary artery disease. General Hospital Psychiatry, 29(5), 417–424.

Bjelland, I., Dahl, A. A., Haug, T. T., & Neckelmann, D. (2002). The validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. An updated literature review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 52(2), 69–77.

Cameron, I. M., Crawford, J. R., Lawton, K., & Reid, I. C. (2008). Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 58(546), 32–36.

Malasi, T. H., Mirza, I. A., & el-Islam, M. F. (1991). Validation of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale in Arab patients. Acta Psychiatrica Scand., 84(4), 323–326.

Swinson, R. P. (2006). The GAD-7 scale was accurate for diagnosing generalised anxiety disorder. Evidence Based Medhod, 11(6), 184.

Lowe, B., Decker, O., Muller, S., Brahler, E., Schellberg, D., Herzog, W., et al. (2008). Validation and standardization of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Screener (GAD-7) in the general population. Medical Care, 46(3), 266–274.

Spitzer, R. L., Kroenke, K., Williams, J. B., & Lowe, B. (2006). A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine, 166(10), 1092–1097.

Andersson, G., Carlbring, P., Kaldo, V., & Strom, L. (2004). Screening of psychiatric disorders via the Internet. A pilot study with tinnitus patients. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 58(4), 287–291.

Belli, S., Belli, H., Bahcebasi, T., Ozcetin, A., Alpay, E., & Ertem, U. (2008). Assessment of psychopathological aspects and psychiatric comorbidities in patients affected by tinnitus. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology, 265(3), 279–285.

Konzag, T. A., Rubler, D., Bandemer-Greulich, U., Frommer, J., & Fikentscher, E. (2005). Psychological comorbidity in subacute and chronic tinnitus outpatients. Zeitschrift für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie, 51(3), 247–260.

Weber, J. H., Jagsch, R., & Hallas, B. (2008). The relationship between tinnitus, personality, and depression. Zeitschrift für Psychosomatische Medizin und Psychotherapie, 54(3), 227–240.

Hesse, G., Rienhoff, N. K., Nelting, M., & Laubert, A. (2001). Chronic complex tinnitus: Therapeutic results of inpatient treatment in a tinnitus clinic. Laryngo-Rhino-Otologie, 80(9), 503–508.

Schaaf, H., Eipp, C., Deubner, R., Hesse, G., Vasa, R., & Gieler, U. (2009). Psychosocial aspects of coping with tinnitus and psoriasis patients. A comparative study of suicidal tendencies, anxiety and depression. HNO, 57(1), 57–63.

Mazurek, B., Olze, H., Haupt, H., & Szczepek, A. J. (2010). The more the worse: The grade of noise-induced hearing loss associates with the severity of tinnitus. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 7(8), 3071–3079.

Konzag, T. A., Rubler, D., Bloching, M., Bandemer-Greulich, U., Fikentscher, E., & Frommer, J. (2006). Counselling versus a self-help manual for tinnitus outpatients: A comparison of effectiveness. HNO, 54(8), 599–604.

Simpson, R. B., Nedzelski, J. M., Barber, H. O., & Thomas, M. R. (1988). Psychiatric diagnoses in patients with psychogenic dizziness or severe tinnitus. Journal of Otolaryngology, 17(6), 325–330.

D’Amelio, R., Archonti, C., Scholz, S., Falkai, P., Plinkert, P. K., & Delb, W. (2004). Psychological distress associated with acute tinnitus. HNO, 52(7), 599–603.

Goebel, G., Kahl, M., Arnold, W., & Fichter, M. (2006). 15-year prospective follow-up study of behavioral therapy in a large sample of inpatients with chronic tinnitus. Acta Oto-Laryngologica. Supplement, 556, 70–79.

Stobik, C., Weber, R. K., Munte, T. F., Walter, M., & Frommer, J. (2005). Evidence of psychosomatic influences in compensated and decompensated tinnitus. International Journal of Audiology, 44(6), 370–378.

Zöger, S., Svedlund, J., & Holgers, K. M. (2006). Relationship between tinnitus severity and psychiatric disorders. Psychosomatics, 47(4), 282–288.

Mathew, R. J., Weinman, M. L., & Mirabi, M. (1981). Physical symptoms of depression. British Journal of Psychiatry, 139, 293–296.

Andersson, G. (2002). Psychological aspects of tinnitus and the application of cognitive-behavioral therapy. Clinical Psychology Review, 22(7), 977–990.

Harrop-Griffiths, J., Katon, W., Dobie, R., Sakai, C., & Russo, J. (1987). Chronic tinnitus: Association with psychiatric diagnoses. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 31(5), 613–621.

Mergl, R., Seidscheck, I., Allgaier, A. K., Moller, H. J., Hegerl, U., & Henkel, V. (2007). Depressive, anxiety, and somatoform disorders in primary care: Prevalence and recognition. Depress Anxiety, 24(3), 185–195.

Hope, M. L., Page, A. C., & Hooke, G. R. (2009). The value of adding the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire to outcome assessments of psychiatric inpatients with mood and affective disorders. Quality of Life Research, 18(5), 647–655.

Belli, H., Belli, S., Oktay, M. F., & Ural, C. (2012). Psychopathological dimensions of tinnitus and psychopharmacologic approaches in its treatment. General Hospital Psychiatry, 34(3), 282–289.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zirke, N., Seydel, C., Arsoy, D. et al. Analysis of mental disorders in tinnitus patients performed with Composite International Diagnostic Interview. Qual Life Res 22, 2095–2104 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0338-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-012-0338-9