Abstract

Drawing from group theories of race-related attitudes and electoral politics, we develop and test how anxiety influences the relative weight of prejudice as a determinant of individuals’ support for racial policies. We hypothesize that prejudice will more strongly influence the racial policy preferences of people who are feeling anxious than it will for people who are not. Using an experimental design we manipulate subjects’ levels of threat and find significant treatment effects, as hypothesized. We find that individuals’ racial policy attitudes are partially conditional on their affective states: individuals who feel anxious report less support for racial policies than those individuals who do not feel anxious, even when this threat is stimulated by non-racial content. More broadly, we conclude that affect is central to a better understanding of individuals’ political attitudes and behaviors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

The debate over the sources of white Americans’ attitudes about policies directed at racial and ethnic minorities has persisted for more than 40 years, with little sign of abating. Scholars focus primarily on two competing explanations for whites’ lack of support for public policies intended to benefit African-Americans, and identify a third as well. Advocates of the symbolic racism perspective claim that racial prejudice (i.e., negative, stereotypical views toward African-Americans) motivates whites’ opposition to race-related policies. In contrast, proponents of the principled politics perspective assert that attitudes on racial policies result instead from citizens’ political ideology and commitment to individualistic principles. Realistic group conflict theorists argue instead that individuals’ race-related attitudes reflect some real or perceived threat that improvements in the economic, social or political status of one group necessarily come at the expense of more privileged groups. Empirical research has yielded evidence reflective of each of these perspectives, though more attention has been paid to the “principles vs. prejudice” debate (for a representative sample of these and related perspectives see Sears et al. 2000).

That the intellectual contours of this debate may be shifting, or at least need to shift, is suggested by Feldman and Huddy’s (2005) experimental evidence that racial resentment—used most often as an indicator of symbolic racism—is not a valid general measure of racial prejudice. Instead, Feldman and Huddy conclude that the racial resentment scale seems to reflect prejudice for liberals and ideology for conservatives (though less strongly); therefore racial resentment “means different things to liberals and conservatives” (but see Henry and Sears 2002; Tarman and Sears 2005). This important measurement issue certainly helps to explain why the exhaustive efforts to determine whether prejudice or principles determines individuals’ racial policy attitudes have produced such contradictory (and at the same time convincing) evidence.

Indeed, scholars who have used unobtrusive measures of racial prejudice or relied on experimental research designs have concluded that whites’ attitudes on race-related policies are not solely determined by racial prejudice. Kuklinski et al. (1997), for example, find that racial prejudice accounts for some, but not all, of whites’ resistance to affirmative action programs and that whites’ attitudes toward affirmative action are not “unyielding and unalterably fixed” (1997, p. 402). More recently, Branton and Jones (2005) posit that support for racial policies (or social issues, as they call them) is conditional to the extent that such attitudes are influenced by varying racial and socioeconomic contexts. These recent studies raise critical questions regarding the heterogeneity of the sources and consequences of racial policy attitudes across individuals as well as contexts. To what extent do the determinants of attitudes toward racial policy vary across individuals? Under what conditions? And to what extent might the relative importance of ideology and prejudice be altered by the nature of contemporary debates on race policy?

We offer an initial response by re-visiting the concept of threat as a common thread in group theories of racial attitudes, and by taking threat more seriously as an emotional influence on individuals’ racial policy preferences. We argue that when individuals feel threatened and are anxious, prejudice more strongly explains their attitudes on racial policies. We expect that the effects of anxiety in heightening the impact of prejudice will be evidenced even if the source of the threat is race-neutral. Thus, we shift the approach of previous research focusing on threat as individuals’ calculations or evaluations of the political or economic threat imposed by out-groups to threat as a psychological state with consequences for individuals’ policy preferences.

To be clear, we do not seek to determine whether it is prejudice or ideology which forms the foundation of whites’ opposition to racial policies. Instead, we seek to determine how the effects of prejudice on whites’ attitudes toward racial policies vary according to individuals’ psychological states. Given the emotionally-charged nature of most debates surrounding racial policies (as well as the increasingly polarized partisan context of many policy debates today), we believe this approach contributes both to our intellectual understanding of the determinants of the sources of whites’ race-related policy attitudes as well as to the importance of contemporary elite dialogue and debate to understanding citizens’ policy views.

Our primary intellectual contribution is in integrating what we know about anxiety as an affective reaction and individuals’ attitudes toward racial policies. Despite the fact that the most recent unobtrusive measures of prejudice ask individuals what they are angry about, and “race-related” anger is regularly observed in elite and mass political behavior, we have no systematic evidence as to how or whether individuals’ affective states fundamentally alter the determinants of their racial policy preferences. Our experimental evidence suggests indeed that when individuals’ affective states are changed by a threat stimulus, their opinions toward race-related policies are influenced more heavily by prejudicial racial attitudes than by ideology.Footnote 1

Racial Policy Preferences

As Hutchings and Valentino (2004, p. 389) note in their recent review essay, the “…debate over the impact of racial attitudes on policy preferences has been among the most contentious in all of public opinion research.” That debate has typically been framed as either/or: either prejudice explains whites’ race-related policy attitudes, or political principle does—with little room for these alternative theories to co-exist. Yet Hutchings and Valentino rightly observe that both indicators of prejudice and indicators of principle are almost always strong and consistent predictors of individuals’ race-related attitudes.

A third model of racial attitudes, realistic group conflict theory, argues that when groups compete over scarce resources, inter-group attitudes become more negative. In addition, it “emphasizes that there tends to be a connection between real dominant group interests and subjective group perceptions of their own interests” (Quillian 1995, p. 588). As such, to the extent that blacks pose a threat to whites’ superior economic, political, or social positions, whites will oppose any government policies that seek to redress such imbalances. Bobo’s (2000) analysis supports this model: whites and blacks have similar perceptions of the costs and benefits of affirmative action, and adopt policy positions in accordance with their group interests. Moreover, these interests are significant predictors of individuals’ positions on affirmative action, even while controlling for individualism and prejudice.

Moving beyond the dominant either/or debate (and giving realistic group conflict theory a fair hearing) requires, we believe, considering more seriously the notion of threat shared by all three models of group politics. The role of emotion in prejudice has a long history, dating back at least to Allport’s recognition that “Defeated intellectually, prejudice lingers emotionally” (Allport 1954, p. 311). This recognition plays an important role in the theoretical framework of symbolic racism. Kinder and Sears (1981) argue that “symbolic racism is rooted in …early learned racial fears.” Later Sears (1988) suggests that symbolic racism manifests itself as “fear, avoidance and a desire for distance, anger, distaste, disgust, contempt apprehension, unease, and dislike.”

The key conceptual role of threat in the symbolic racism model is underscored by Kinder and Sanders’ (1996) observation that the “nature of race” changed between the 1960s and 1970s in response to both the growing rejection of biological racism and the increased perceived threat posed by (inner-city) African Americans. According to Kinder and Sanders, the nature of whites’ prejudice shifted from overt racism to racial resentment, a more subtle stereotyping of blacks accompanied by a sense that they violate certain moral values and hence do not “deserve” special treatment. In short, the societal foundation of racial resentment is the threat whites perceive from African Americans—a claim that is hard to dispute given contemporary rhetoric over affirmative action policies. As Kinder and Sanders (1996, p. 90) argue: “The perception of threat has a systematic foundation, but the foundation is provided not by actual conditions of conflict and competition but by feelings of racial resentment. Threat is not so much a clear-eyed perception as it is an emotion-laden attitude.”

Threat has also played a central role in realistic group conflict theory and its variants (including group position and social dominance theories) dating back at least to Blumer (1958). Sears et al. (2000, pp. 23–24) note that this threat is most evident at the group, rather than individual level, and the mere perception (as opposed to reality) of threat may be sufficient for resulting negative attitudes on the part of whites. Most studies of the racial group threat hypothesis have relied on aggregate-level data measuring the size or other (socioeconomic) attributes of the Black population, positing that larger and higher status Black populations pose greater threats to Whites.

Mendelberg’s (2001) evidence that implicit racial cues tap into whites’ fear and resentment toward African-Americans and influence their candidate evaluations and policy attitudes also points more broadly to the fundamental importance of threat to understanding race-related attitudes. She concludes that elites can indirectly appeal to such prejudices by using symbols such as welfare as part of campaign rhetoric and strategy, and that such appeals are effective. Thus, the impact of prejudice is variable, contingent in part on contemporary political rhetoric.

Social psychological evidence on the nature of prejudice supports the notion that threat and anxiety play an important role in whites’ prejudice in general and toward African Americans specifically. In general, anger and fear play an important role in explaining people’s actions and attitudes about any out-group (Mackie et al. 2000) and fear and anxiety are an essential element in outgroup paranoia (Kramer and Jost 2002). As social psychologists have begun to unpack the complex nature of prejudice, they have delineated its nuanced emotional underpinnings (Mackie and Smith 2002). Cottrell and Neuberg (Cottrell and Neuberg 2005; Neuberg and Cottrell 2002), for instance, document how whites’ prejudice against three different ethnic groups has different emotional foundations. Consistent with the (often ignored) emotional aspects of symbolic racism theory, for whites, fear and anxiety feelings were highest when stimulated by or directed toward African Americans.

In sum, we draw two relevant conclusions from our readings of the racial attitudes and prejudice literatures. First, threat is a key factor in each of the three dominant models of group politics, whether it is a threat of an out-group, of privilege, of deeply-held political principle, or some combination thereof. Second, drawing on both the symbolic racism literature and the social psychological literature on the nature of prejudice, affective reactions associated with African Americans tend to include feelings of fear, threat, and anxiety.

Anxiety, Threat, and Attitudes

Our argument regarding racial policy attitudes might well seem familiar, or even expected, given recent research on the diverse and complex ways in which affect and cognition serve independently or together to influence individuals’ political attitudes, information-seeking, and voting behavior (see, for example, Cacioppo and Gardner 1999; Conover and Feldman 1986; Gross 2008; Just et al. 1996; Ladd and Lenz 2008; Lau and Redlawsk 2001; Nadeau et al. 1995; Redlawsk 2002; Valentino et al. 2008).

Initially, our theoretical argument was motivated by Marcus and his colleagues’ work on affect and tolerance (Marcus et al. 1995). Their theory explaining why people often express intolerant attitudes is based on Jeffrey Gray’s work in neuropsychology on emotions (see, for example, Gray 1987a, b, 1990, 1991; Gray and McNaughton 1996). According to Gray, the role of the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS) is to scan the environment for things that are unexpected. The BIS compares what it senses to the mental script we hold for what is expected. If it detects something that does not fit, then it interrupts cognitive processes and focuses our attention on whatever is “out of the ordinary” by raising our level of anxiety. If the unusual occurrence is a threat, anxiety increases even more, and our physiology cues us to resolve the threatening situation. In the case of tolerance concerns, the remedy is to seek the power of the government to prevent the threatening group from exercising their free speech rights. In general, the attitudes that result from these feelings of threat are supportive of policies or practices that squelch the source of the anxiety.

It is important to note that even when thinking about racial policy attitudes, this initial threat—the stimulus that engages the BIS—does not need to be linked to race. If Marcus and colleagues are correct, then any threat should make a person more sensitive to added threats, even if the threat stimulus and subsequent policy attitude are completely unconnected. Related, in subsequent work Marcus and colleagues (2005) consider the consequences of extrinsic anxiety, i.e., anxiety unrelated to the attitude object at hand. This research suggests that being anxious about one attitude object can have “carry over” effects and result in a greater response to a second attitude object. In short, when individuals feel anxious about one attitude object (i.e., issue), this anxiety is reflected in attitudes toward other objects or issues.

Small and Lerner (2008) confirm the existence of such “carry over” effects in their study of individuals’ decisions on appropriate levels of welfare assistance. Their experimental manipulation was to ask subjects to think and write about something in their personal lives that made them feel angry or sad. Then, in what was portrayed as a second experiment, subjects were asked what the appropriate level of welfare payment was for a particular case. They found that subjects who were angry preferred lower welfare payments, while subjects who were sad preferred higher welfare payments. They conclude not only that “incidental” emotions influence individuals’ policy preferences, but also that the mechanism by which such effects were translated was a difference in the depth of cognitive processing, i.e., sadness resulted in higher payments because it, unlike anger, induced greater thought.

In sum, studies of the role of anxiety and threat in the formation of individuals’ political attitudes suggest that threats and other sources of anxiety have more than just cumulative effects. A person’s response to sources of anxiety depends partially on their pre-existing levels of anxiety. Returning to our discussion of the antecedents of racial policy attitudes above, this implies that the effect of racial attitudes (because they stem at least partially from feelings of anxiety and threat) should depend on the pre-existing level of anxiety a person feels when constructing their racial policy attitude. Racial resentment should be a stronger predictor of racial policy attitudes for people who feel relatively anxious than it is for people who feel relatively calm.

We will, as described below, test this by experimentally manipulating the feelings of anxiety of our subjects. Thus, we will expect that the manipulation will moderate the use of symbolic racism on racial policy attitudes. Moreover, we will also measure the level of anxiety of our subjects directly after the manipulation. If our theory is correct, then this level of anxiety should mediate the moderation due to the experimental manipulation.

Experimental Design

In an effort to both integrate and advance the literatures on racial attitudes and emotion, we have developed a relatively straightforward hypothesis: individuals who are threatened by non-racial stimuli will rely more on their prejudice towards African Americans than people who are not threatened.

Central to testing our hypothesis is an experimental manipulation that puts subjects in a threatened state. Our theory suggests that the manipulation can be wholly disconnected from race, which is also desirable from a practical perspective as well: priming individuals’ racial attitudes by using a race-related threat stimulus would certainly limit, if not eliminate, any confidence we have as to the internal validity of our design. Instead, we want to manipulate the level of threat the subject feels independent of these other concerns, i.e., to stimulate anxious reactions independent of any “substantive” priming of race-related issues or attitudes. Of course, we also need valid measures of our primary variables of interest—racial policy preferences and levels of prejudice—as well as the level of anxiety subjects reported experiencing after the manipulation to ensure that the treatment was effective. In this section we describe each of these elements of our study.

The experiment took place at Texas A&M University in a required undergraduate course on American politics. 153 undergraduates participated in the study, of which 142 completed all of the necessary components of the experiment for inclusion in our analysis. 51 percent of the subjects were female, 140 were aged 18–22, and only 3 of the subjects were African-American.Footnote 2 The first stage of the experiment was a brief paper survey, asking individuals standard (closed-ended) demographic and attitudinal questions regarding their race, gender, year in school, citizenship status, ideology, and partisanship.

The second, and most challenging, stage of the design was the manipulation to alter the subjects’ threat levels. Given our reliance on the tolerance literature, we decided to mimic one of the more successful threat manipulations in the literature and followed the example of the experiments conducted by Marcus et al. (1995). Their interest lay in how cognition and affect altered levels of tolerance. To manipulate subjects’ feelings of anxiety and threat they gave the subjects one of two articles about a hypothetical group. The manipulation was to change the tone of the language and the belligerence of the group. Their results indicate that the subtle differences in language effectively caused subjects to feel different levels of threat from the stimuli.

The specific manipulation we used to alter how threatened the subjects felt was presenting them with one of two articles regarding animal rights protestors on college campuses.Footnote 3 Again, the theory of emotions and threat outlined earlier suggests that the level of threat a person feels should alter how they form policy opinions, not necessarily what they report as their opinion. Thus, although the manipulation is directed at information about animal rights activists, the differences in the (manipulated) threat levels should be reflected in the considerations individuals use in responding to policy opinion questions.

What if we are incorrect? What would the result be if the manipulation did not affect the broader sense of threat of the subjects? If indeed, our manipulation focusing on animal rights activists fails, we would be less likely to observe any treatment effects and therefore be more likely to accept the null hypothesis. Thus, we believe that the disjuncture between the subject of the manipulation and the subject of the attitudes we are interested in introduces a conservative bias, if any, and thus may lead us to understate the effects of threat on constructing racial policy attitudes.

The articles on animal rights organizations’ activities on college campuses were fictitious, designed to look like photocopies of typical magazine news stories. Their basic structures and layouts (including the number and placement of photos) were identical (see Appendices 1 and 2 for the full text of the two treatments). The only “substantive” differences between the two articles were the descriptive names of the animal rights groups (either “activists” or “terrorists”) and the kind of threat each group posed (collateral versus human life). Our expectation was that subjects reading the treatment story describing a loss of human life would feel more threatened than those reading the story describing building damage only.

After reading the story, subjects were instructed to complete a post-manipulation survey which consisted of several types of questions. The first question asking if “government should make every effort to protect scientists” served as a cover to our true interest in racial policy attitudes. Immediately following this question was our measure of individuals’ attitudes toward affirmative action: “Some people think that because of past discrimination blacks should be given preference in hiring and promotion. Others think that such preference in hiring and promotion of blacks is wrong because it gives blacks advantages they haven’t earned. What do you think?” Later in the survey subjects were asked a second question about race policy, the standard NES seven point scale: “Some people think that the government in Washington should make every effort to improve the social and economic position of blacks. Others think that the government should not make any special effort to help blacks because they should help themselves. What do you think?” The dependent variable in the analyses that follow is an additive scale built out of these two measures.Footnote 4

The rest of the survey included a set of questions we used to construct a symbolic racism scale as well as standard NES measures of traditional values, trust in government, and a few policy questions intended to distract subjects from the true focus of our study. None of these questions demonstrated any effect from the experiment.Footnote 5

Four questions drawn from the “symbolic racism 2000 scale” were used to construct an additive scale of symbolic racism (α = 0.67; see Henry and Sears 2002):

-

Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statement: “Irish, Italians, Jewish and many other minorities overcame prejudice and worked their way up. Blacks should do the same without any special favors.”

-

Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statement: “Generations of slavery and discrimination have created conditions that make it difficult for blacks to work their way out of the lower class.”

-

Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statement: “Over the past few years, blacks have gotten less than they deserve.”

-

Please indicate how much you agree or disagree with the following statement: “It’s really a matter of some people not trying hard enough; if blacks would only try harder they could be just as well off as whites.”

Again, these questions were interspersed with several other questions in order to minimize potential problems of correlated measurement error. One concern about this measure, however, is that it occurs after the manipulation. In our pilot test, we included the symbolic racism questions before the actual manipulation, but in our debriefing of these pilot subjects we found that the subjects were confused and distracted by the study design. They knew, based on these questions, that we were interested in their attitudes on race, but were perplexed by having to read an article on animal rights organizations that didn’t seem to “fit.” To address this issue, we placed the symbolic racism scale after the manipulation. We believe that this change worked. In our debriefing of the actual subjects, none of them thought that this experiment was explicitly about race.

The last set of questions in the post-manipulation survey provides some evidence for a manipulation check. Here we asked subjects about their emotional reactions to animal rights groups using question-wording derived from standard NES items asking individuals how they feel about presidential candidates. The only difference is the target of the questions. Instead of asking if a candidate ever made the subject feel anxious, angry, hopeful, and proud, for example, we asked whether an animal rights organization has ever made them feel anxious, angry, hopeful, and proud.

Methods

The hypothesis we wish to test is the conditional nature of attitudes about prejudice on racial policy preferences and how threat and anxiety moderates the use of prejudice when forming racial policy preferences. Unlike most experimental designs, we are not hypothesizing about the main effect of our manipulation on the dependent variable. Rather, we are interested in how the manipulation moderates the use of pre-existing attitudes. The test for this type of moderating relationship is straightforward (Baron and Kenny 1986). We model the effect of racial prejudice on racial policy preferences via OLS. The moderating effect of the manipulation, then, is specified through an interaction term between racial prejudice and which experimental condition the subject is in. This interaction term is the test of our hypothesis.

We will also test if the experimental manipulation alters the role either ideology or party plays in predicting racial policy preferences. We are interested in the link between threat and racial attitudes. It might be possible, however, that the effects of the manipulation spill over into the effect of other predictors of racial policy attitudes. Thus, as controls, we include the same interactions between the experimental condition and ideology and party.

We can do more than just test if the experimental condition moderates the use of racial prejudice, however. Our theory suggests that this moderation occurs because of the sense of anxiety and threat the subjects feel. We include measures of this anxiety in the post-test. Therefore, we can test for mediated moderation. The standard test of mediation (Baron and Kenny 1986) is a three step process. First, scholars need to show that the experimental manipulation created differences in the mediator (anxiety). We will show this through some manipulation checks early in our results. Second, the scholar should estimate a regression where the experimental condition creates differences in the dependent variable. In this case, the “dependant variable” is effect of symbolic racism and ideology on racial policy attitudes. The third step in demonstrating a mediating relationship is to show that once the mediator (anxiety) is accounted for, the effect of the experimental treatment is either diminished, for partial mediation, or eliminated (what Baron and Kenny refer to as perfect mediation).

The test of mediation requires one more step. Given the multicollinearity induced by adding all of these variables to the model, the correct specification includes a test of the indirect effect of the manipulation on the use of symbolic racism on racial policy attitudes. If this indirect effect is significant, then we can conclude that the effect is mediation by the subject’s anxiety. The classic test for this indirect effect is the Sobel (1982) test. This technique, however, is biased in small samples. Instead, we will use the bootstrap to calculate the standard error of the indirect effect (Preacher and Hayes 2004).

Results

Before turning to the specific hypothesis tests, we report the results of our two manipulation checks. Again, the manipulation was designed to elicit threat and therefore heighten anxiety for the treatment group. If the manipulation worked, we should see two things. First, if the manipulation in the story changed the level of threat the subject felt, then individuals in the “threatening” treatment condition should have been more supportive of protections for scientists (the first question we asked following the manipulation) than individuals in the “non-threatening” condition. Second, we should also see significant differences between the two treatments in the level of anxiety about the animal rights groups.

To test this we use two of the affective measures included at the end of the final survey.Footnote 6 Note that these questions were asked after all of the other questions used to measure our independent and dependent variables, a sizable time gap between the stimuli and the responses here. If differences exist for these questions across conditions, the threat levels are likely to be different across the treatment groups as they responded even earlier to the question measuring our dependent variable as well. We combined the two different affect questions into a single measure tapping the subjects’ anxiety (being angry and anxious) about these groups.

We also want to make sure that there are no differences in the independent variables across the conditions. The hypothesis is that the level of threat the subject feels as a result of the manipulation will alter the psychological process that explains individuals’ attitudes toward race-related policy by differentially weighting individuals’ prejudice and ideology as predictors of opinion on racial policies rather than by increasing individuals’ absolute levels of prejudice and ideology. The possibility of the treatment altering individuals’ levels of prejudice is a concern because the measurement of these attitudes occurred after the manipulation. If indeed the treatment enhanced levels of prejudice, then we should see significant differences in these attitudes across treatment groups. Additionally, while random assignment should create an equal balance of ideologies in our conditions, this assumption is worth checking as well.

Table 1 presents the simple t-tests of the manipulation checks. The first row presents the means and statistical tests of differences across the groups on the support for the “protection of scientists” question, while the second and third rows show the same for the anxiety and enthusiasm measures. The results suggest that the manipulations worked. The mean level of support for protecting scientists and the mean level of anxiety are significantly higher for subjects in the threatening condition than in the non-threatening condition (with t-values of 2.05 and −2.12, respectively). We interpret this as evidence that the experimental manipulation of the news articles about animal rights groups succeeded in making individuals in the threatening condition feel more threatened than the non-threatening condition. Thus, we expect that differences we see across treatment groups stem from differences in the threat levels of the respondents. We shall return to this expectation more directly later.

The third and fourth rows report the t-tests of the mean difference across experimental groups for the ideology and prejudice measures. Neither prejudice nor ideology is significantly different across groups. Thus, we are confident that our manipulation worked, and that it had no unintended effects for levels of our primary independent variables of interest.

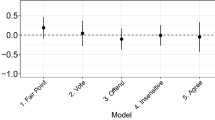

Testing our hypothesis is relatively straightforward. We estimate a regression model where the individual’s attitude on race-related policy is specified to be a function of the experimental condition (0 if in the baseline, non-threatening condition, and 1 if in the threatening condition), ideology, symbolic racism and partisanship. We then add interaction terms consisting of the treatment (threat) condition and ideology, symbolic racism and partisanship. The hypothesized differences in the effects of symbolic racism and ideology are tested using their respective interaction terms. The interaction terms test whether the effects of symbolic racism and ideology differ across conditions. Significant estimates for these interaction terms indicate that individuals in the threatening, affective condition weight modern racism or ideology differently than individuals in the control condition. These results are presented in the first column of Table 2.

The effects of partisanship indicate that party simply did not matter for the subjects’ racial policy attitudes. Neither of the coefficients indicating the effect of partisanship are statistically significant at traditional levels and they are also jointly insignificant (F (2, 134) = 0.68; p > 0.50). Thus, we find no evidence of a main effect of partisanship on attitudes toward racial policies, or of differential effects across the threatening and non-threatening treatments or of the total effect of partisanship across groups. Some of this may be due to the collinearity between partisanship and ideology (ρ = 0.69), but even if we omit the ideology measures from the model, partisanship is insignificant.

In contrast, support for our hypothesis is strong for symbolic racism: the significant symbolic racism/threat interaction term suggests that the effect of prejudice is heightened when individuals are in an increased threat state. Thus, symbolic racism has a greater effect on individuals’ attitudes toward racial policy when they feel threatened. And the substantive impact of this shift is notable: the effect of symbolic racism is more than double in the threatening, vs. non-threatening, condition. Consistent with much previous research, the main effect is also significant, indicating that higher levels of symbolic racism lead to decreased support for racial policies even in the non-threatening scenario.

The results for ideology show that the manipulation did not influence the link between ideology and racial policy preferences. As with symbolic racism, the non-interactive coefficient for ideology on attitudes toward race-related policy is significant: in the non-threatening condition, ideology exerts a significant influence on the subject’s attitude about race-related policy, with conservatives more opposed to steps to help African Americans than liberals. Unlike the case for symbolic racism, however, the interaction term between the treatment (threat) condition and ideology is insignificant.Footnote 7

At this point, we know that the predictors of racial policy preferences differ across our experimental conditions. Our hypothesis is that this is due to the threat induced by our manipulation and the heightened level of anxiety the subjects felt. We have not directly tested this yet, however. Our argument is that the effect of the experimental manipulation is mediated by changes in the anxiety that the subjects felt. Our data allow us to test for this mediation.

As noted above, testing for mediation is a three step process. The first step is in Table 1 where we show that the experimental manipulation created differences in the levels of anxiety. The first column of Table 2 presents the second step, demonstrating that the manipulation does moderate the use of racial prejudice. The second and third columns of Table 2 complete the analyses. The second column of Table 2 replaces the interactions with the experimental treatment with interactions with the direct measure of how anxious the person felt about these groups—the same measure used in Table 1.Footnote 8 The third column combines both models and includes interactions with the treatment indicator and the anxiety measure.

The results support the mediational role of anxiety. In the second column, the significance pattern of the interactions is the same as in first. Symbolic racism is moderated by the level of anxiety the person feels. The key results are found in the third column, where the interaction between symbolic racism and the level of anxiety is statistically significant. And once this effect is accounted for, the interaction between symbolic racism and the treatment is no longer significant. Moreover, our results suggest that over one-third of the moderating effect of our manipulation is mediated by these anxiety measures; we suspect that a better measure of anxiety would likely find a larger mediating effect.

The bootstrapped Sobel test is supportive of the mediational effect of this anxiety measure. The estimated indirect effect of the manipulation on the effect of symbolic racism on racial policy attitudes is 0.06, with a bootstrapped standard error of 0.04. The bias corrected 95 percent confidence intervals for the test statistic are 0.03 and 0.18.Footnote 9 In summary, our finding that the manipulation altered the effect of symbolic racism on racial policy attitudes is a result of the mediating influence of anxiety on this relationship.

Conclusion

Our interest in the conditional nature of individuals’ racial policy attitudes is certainly not unique. Sniderman, for example, has advocated scholars move away from explaining what predicts attitudes or behaviors toward uncovering why these effects differ across individuals. He and his colleagues noted that they expected to be “surprised if the presupposition of causal heterogeneity… is not as fruitful for others as it has been for us” (Sniderman et al. 1991, p. 264). Our results suggest that moving beyond a horse race between principled politics and prejudice or among various group models of politics, and focusing on this heterogeneity is indeed an intellectually-valuable enterprise.

Our results suggest that a person’s emotional state may influence how much or little they rely on symbolic racism. When respondents are threatened, symbolic racism is a stronger predictor of their attitudes toward race-related policy than when they are not threatened. We believe this key empirical finding helps to move us away from the “either/or” stalemate that research on racial attitudes seems to have approached, and lends insight into the potentially varying nature of individuals’ attitudes toward racial policies. This finding also leads to important new questions regarding individual differences in responsiveness to threat and the efficacy of different sources of communication in stimulating threat-responses. Additional research must also be done to determine more precisely the breadth of race-related policies for which individuals respond to threat in similar ways, and whether such responses might also occur in non-race-related policy areas.

We acknowledge, however, that the increased sensitivity to the threat connected to racial resentment is not the only possible explanation for the patterns we have observed. We have suggested that increasing the threat one feels will heighten the use of racial resentment in forming racial policy attitudes, even if this threat is non-racial in nature. One other possibility is that threat heightens the person’s sense of authoritarianism or the relative effect of authoritarianism beliefs on racial policy attitudes (Stenner 2005).Footnote 10 As Duckitt notes, several studies have indicated a relationship between authoritarianism and threat (2003, pp. 576–577). This evidence might suggest that changes in the level or effects of authoritarianism, and not sensitivity to threat itself, may be partly responsible for what we observed. Unfortunately, we did not measure the levels of authoritarianism, but this and other potential mediators of non-racial threat should be tested to more fully understand the complex interplay of threat and racial attitudes. We hope that this avenue of research, too, will prove fruitful for future scholars.

More generally, these results underscore the centrality of affect to understanding individuals’ political attitudes and behavior. Previous research has focused on how affective reactions to a particular object affect attitudes or behavior about the same object. Marcus et al. (1995) demonstrate, for example, that individuals who are threatened by a group will hold more intolerant attitudes toward that particular group. Importantly, our results suggest that our emotional state about one thing can spill over to our reactions to other politically meaningful objects. If being threatened by animal rights activists structures how individuals form attitudes about racial policy, then other issues may also be responsive to such “indirect” affective influences and one can imagine a new complexity in understanding the nature of public opinion toward a wide range of issues.

We are not the first to note the spillover effects of threats (e.g., Small and Lerner 2008; Marcus et al. 2005). But we think it is worth commenting further on this important point. Our results suggest that a threatened person makes very different decisions than a person who is not threatened, even in areas unrelated to the nature of the threat. Given the role of threat in changing the nature of decision making, the implications of this are quite broad. For instance, Brader (2006) finds that threatening ads make voters rely less on party and more on the candidates when voting. Our results suggest that the effect does not have to stem from the advertising done about the candidate him or herself. If a threatening commercial about an unrelated topic (e.g. a new movie) that scares the viewer precedes a commercial about the candidate, this advertising placement may alter the foundations of political judgment even though it is entirely apolitical. Clearly, we do not test this supposition, but it does suggest that the implications of this and other work on threat and anxiety deserve further attention.

Our results also speak to the nature of whites’ racial policy preferences in a way that integrates the three dominant models of racial group attitudes from the perspective of the mechanism of threat. Rarely do “either/or” debates in the social sciences lead to the dominance of one perspective and failure of another. Instead, they force scholars to consider more complex models of political attitudes and behavior. We view our results as affirming the critical role of affect and threat in understanding individuals’ racial attitudes, and suggest that future research seek to incorporate the emotions of race into the evaluations of the more standard models we typically discuss. Ideology and racial attitudes are relatively stable, and typically change more slowly relative to other political attitudes and policy positions (Kellstedt 2003; Stimson 1999). In contrast, people’s emotions change relatively rapidly, often varying widely during a single day and sometimes from moment to moment. Popular perceptions of the dynamics of election campaigns often hinge on the emotional aspects of race in politics today, with politicians sometimes benefitting and sometimes losing from such dimensions. Whether these “momentary” shifts will amount to any substantial or notable shifts in the public’s positions on race-related policies such as affirmative action is yet another question to be addressed in future research.

Notes

For ease of exposition, we use the terms symbolic racism, racial resentment and modern racism interchangeably through the paper, and here refer to them collectively as “prejudicial racial attitudes.”

These three subjects are removed from the analysis.

We chose animal rights groups because we felt that they were likely to have no obvious racial overtones that would taint the racial policy preferences questions the way other groups (e.g. the Klu Klux Klan) would likely do.

When the measures are combined in a factor analysis, they have the same factor score to the third decimal place. The additive scale correlates with the factor score at 0.96. The Cronbach’s alpha on the two item scale is 0.70.

We computed t-tests of the responses to the individual items as well as the composite scales and found no statistically significant differences across the treatment and control groups. On the basis of this evidence, we concluded that the treatment did not affect any of these attitudes.

The other two measures, asking if the group ever made the subject feel hopeful or proud tap more into the enthusiasm the individual felt for this group. Neither of these vary significantly across the experimental conditions.

We have also run the models separately for the two indicators of the dependent variable as a bivariate regression. Our tests found no significant differences in the effects of our dependent variables across the indicators.

Note that the anxiety measure is mean centered so the coefficients that are not interaction terms in the tables are the effect of symbolic racism and ideology for those respondents who have average levels of anxiety.

The asymmetry in the variability of the estimated indirect effects is not unusual in small samples (Bollen and Stine 1990). In fact, that is one of the motivations for using the bootstrap.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for this suggestion.

References

Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. New York: Anchor Books.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1173–1182.

Blumer, H. H. M., Jr. (1958). Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pacific Sociological Review, 1, 3–7.

Bobo, L. (2000). Race and beliefs about affirmative action: Assessing the effects of interests, group threat, ideology and racism. In D. O. Sears, J. Sidanius, & L. Bobo (Eds.), Racialized politics: The debate about racism in America (pp. 137–164). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Bollen, K. A., & Stine, R. (1990). Direct and indirect effects: Classical and bootstrap estimates of variability. Sociological Methodology, 20, 115–140.

Brader, T. (2006). Campaigning for hearts and minds: How emotional appeals in political ads work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Branton, R. P., & Jones, B. S. (2005). Reexamining racial attitudes: The conditional relationship between diversity and socioeconomic environment. American Journal of Political Science, 49(2), 359–372.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Gardner, W. L. (1999). Emotion. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 191–214.

Conover, P. J., & Feldman, S. (1986). Emotional reactions to the economy: I’m mad as hell and I’m not going to take it anymore. American Journal of Political Science, 30(1), 50–78.

Cottrell, C. A., & Neuberg, S. L. (2005). Different emotional reactions to different groups: A sociofunctional threat-based approach to ‘prejudice’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 770–789.

Duckitt, J. (2003). Prejudice and intergroup hostility. In D. Sears, L. Huddy, & R. Jervis (Eds.), Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 559–600). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Feldman, S., & Huddy, L. (2005). Racial resentment and white opposition to race-conscious programs: Principles or prejudice? American Journal of Political Science, 49(1), 168–183.

Gray, J. A. (1987a). The neuropsychology of emotion and personality. In S. M. Stahl, S. D. Iversen, & E. C. Goodman (Eds.), Cognitive neurochemistry (pp. 171–190). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Gray, J. A. (1987b). The psychology of fear and stress (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gray, J. A. (1990). Brain systems that mediate both emotion and cognition. Cognition and Emotion, 4(3), 269–288.

Gray, J. A. (1991). Fear, panic, and anxiety: What’s in a name? Psychological Inquiry, 2(1), 77–88.

Gray, J. A., & McNaughton, N. (1996). The neuropsychology of anxiety: Reprise. In D. A. Hope (Ed.), Perspectives on anxiety, panic and fear (Vol. 43, pp. 61–134). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Gross, K. (2008). Framing persuasive appeals: Episodic and thematic framing, emotional response, and policy opinion. Political Psychology, 29(2), 169–192.

Henry, P. J., & Sears, D. O. (2002). The symbolic racism 2000 scale. Political Psychology, 23(2), 253–283.

Hutchings, V. L., & Valentino, N. A. (2004). The centrality of race in American politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 7, 383–408.

Just, M. R., Crigler, A. N., & Neuman, W. R. (1996). Cognitive and affective dimensions of political conceptualization. In A. N. Crigler (Ed.), The psychology of political communication. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Kellstedt, P. M. (2003). Mass media and the dynamic of American racial attitudes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Sanders, L. M. (1996). Divided by color: Racial politics and democratic ideals. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Sears, D. O. (1981). Prejudice and politics: Symbolic racism versus racial threats to the good life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 40, 414–431.

Kramer, R. M., & Jost, J. T. (2002). Close encounters of the suspicious kind: Outgroup paranoia in hierarchical trust dilemmas. In D. M. Mackie & E. R. Smith (Eds.), From prejudice to intergroup emotions: Differentiated reactions to social groups. New York: Psychology Press.

Kuklinski, J. H., Sniderman, P. M., Knight, K., Piazza, T., Tetlock, P. E., Lawrence, G. R., et al. (1997). Racial prejudice and attitudes toward affirmative action. American Journal of Political Science, 41(2), 402–419.

Ladd, J. M., & Lenz, G. S. (2008). Reassessing the role of anxiety in vote choice. Political Psychology, 29, 275–296.

Lau, R. R., & Redlawsk, D. P. (2001). Advantages and disadvantages of cognitive heuristics in political decision making. American Journal of Political Science, 45, 951–971.

Mackie, D. M., Devos, T., & Smith, E. R. (2000). Intergroup emotions: Explaining offensive action tendencies in an intergroup context. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 602–616.

Mackie, D. M., & Smith, E. R. (2002). Beyond prejudice: Moving from positive and negative evaluations to differentiated reactions to social groups. In D. M. Mackie & E. R. Smith (Eds.), From prejudice to intergroup emotions: Differentiated reactions to social groups. New York: Psychology Press.

Marcus, G. E., Sullivan, J. L., Theiss-Morse, E., & Wood, S. L. (1995). With Malice toward some: How people make civil liberties judgments. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marcus, G. E., Sullivan, J. L., Thiess-Morse, E., & Stevens, D. (2005). The emotional foundation of political cognition: The impact of extrinsic anxiety on the formation of political tolerance judgments. Political Psychology, 26(6), 949–963.

Mendelberg, T. (2001). The race card. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University.

Nadeau, R., Niemi, R. G., & Amato, T. (1995). Emotions, issue importance, and political learning. American Journal of Political Science, 39(3), 558–574.

Neuberg, S. L., & Cottrell, C. A. (2002). Intergroup emotions: A biocultural approach. In D. M. Mackie & E. R. Smith (Eds.), From prejudice to intergroup emotions: Differentiated reactions to social groups. New York: Psychology Press.

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers, 36, 717–731.

Quillian, L. (1995). Prejudice as a response to perceived group threat: Population composition and anti-immigrant and racial prejudice in Europe. American Sociological Review, 60(4), 586–611.

Redlawsk, D. P. (2002). Hot cognition or cool consideration? Testing the effects of motivated reasoning on political decision making. Journal of Politics, 64, 1021–1044.

Sears, D. O. (1988). Symbolic racism. In K. Phyllis & T. Dalmas (Eds.), Eliminating racism: Profiles in controversy (pp. 53–84). New York: Plenum Press.

Sears, D. O., Sidanius, J., & Bobo, L. (2000). Racialized politics: The debate about racism in America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Small, D. A., & Lerner, J. S. (2008). Emotional policy: Personal sadness and anger shape judgments about a welfare case. Political Psychology, 29(2), 149–168.

Sniderman, P. M., Brody, R. A., & Tetlock, P. E. (1991). Reasoning and choice: Explorations in political psychology. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Sobel, M. E. (1982). Asymptotic confidence interval for indirect effects in structural equation models. In S. Leinhart (Ed.), Sociological methodology 1982. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Stenner, K. (2005). The authoritarian dynamic. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Stimson, J. A. (1999). Public opinion in America: Moods, cycles and swings (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview.

Tarman, C., & Sears, D. O. (2005). The conceptualization and measurement of symbolic racism. Journal of Politics, 67(3), 731–761.

Valentino, N. A., Hutchings, V. L., Banks, A. J., & Davis, A. K. (2008). Is a worried citizen a good citizen? Emotions, political information seeking, and learning via the Internet. Political Psychology, 29(2), 247–273.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1: Threatening Text

Education & Society/Security

Task Force on Eco- and Animal Rights Terrorism Finds State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges Vulnerable

One common thread that brings the institutions of the National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges (NASULGC) together is their collective involvement in promoting the interests of universities in the discovery of new knowledge. They are now faced with an unprecedented challenge to the traditional autonomy of the academy to educate, to discover, and to use new knowledge in service to their external communities. Eco- and animal rights terrorist groups seek to curtail research (at universities and elsewhere) that relies on the use of animals, biotechnology, and genetically modified organisms that can be used to improve the human condition. Some of these groups are prone to use violence to achieve their goals, and as such they pose real threats to universities and other research facilities. Those in higher education are also faced with the prospect that international terrorists may seek to use their research activities in such a manner as to produce a disaster causing catastrophic loss of life.

At its November 2001 Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., the NASULGC Board of Directors formed a task force on eco- and animal rights terrorism to explore issues caused by these groups. Several telephone conference meetings have been conducted over the last several months and a 2-day workshop in Washington, D.C. in June was convened to deal with the growing problem.

Eco-Terrorism and the Increasing Eco-Terrorist Threat

The FBI defines eco-terrorism as “the use or threatened use of violence of a criminal nature against innocent victims or property by environmentally oriented, sub-national groups for environmental-political reasons, aimed at an audience beyond the target, often of a symbolic nature.” The U.S. Attorney General has formally designated organizations such as the Earth Liberation Front (ELF) and the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) as domestic terrorists. The FBI has named them as the two most dangerous domestic terrorist groups in America, and has stepped up its investigative activities in this area.

The FBI has expressed serious concerns about the growing impact that eco- and animal rights terrorist activities may have on the university community. The agency’s concerns include academicians’ knowledge of the people who work in their laboratories, the possible training for terrorist actions on campus; and the lack of tough federal laws that might deter eco- and animal rights terrorists.

While many research facilities are located on large urban campuses and can be secured from potential attacks, others are located in isolated areas that are far more difficult to secure. Moreover, faculty have expressed concerns about the potential threat of terrorism to their own well-being and to that of their students. Such concerns are heightened at land-grant universities with genetic research interests and rural agricultural research facilities.

Eco- and Animal Rights Terrorism on Campus

Eco- and animal rights terrorists have claimed credit for a large number of attacks on university facilities across the United States, ranging from the burning of a University of California, Davis research facility nearly 20 years ago to the recent destruction of the University of Washington’s Center for Urban Horticulture. Other recent incidents include:

-

Windows, computers and laboratory equipment were destroyed at an undisclosed university’s poultry laboratory.

-

A psychology laboratory was raided, offices trashed, acid poured on the floor, slogans painted on the walls and rats and rabbits removed from the laboratory.

-

ELF claimed responsibility for a bomb that was found outside a research facility before it detonated.

Animal Rights Demonstrator chants “Animals over Humans”

Education & Society/Security

Eco- and animal rights terrorists have also targeted numerous research facilities owned by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and private corporations that partner with universities in research activities. These partnerships may help explain the reluctance of universities to make public the attacks by these terrorist groups. In a report entitled “Illegal Incidents Summary,” the Foundation for Biomedical Research summarizes over 400 acts of terrorism by ELF, ALF, Stop Huntington Animal Cruelty (SHAC), and other organizations.

The Tragedy of Dr. Michael Podell

Since universities are the training ground for future generations of researchers, the loss of a single researcher and/or laboratory has far-reaching implications for the future of the research enterprise. One recent case illustrates how harassment and the threat of violence can affect America’s experimental researchers. Until recently, Dr. Michael Podell of Ohio State University was one of the leading American HIV virus researchers. His research could provide important insights into how HIV and FIV penetrate the brain.

Dr. Podell was harassed and threatened by both People for Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) and ALF for several years. Shortly after his office phone number and e-mail address were disclosed on their web pages, he began receiving death threats. Despite a USDA surprise visit to OSU and Dr. Podell’s laboratory that found them in compliance with experimental animal policy, the harassment continued. Dr. Podell’s lab was fire-bombed one early morning: the university has not decided whether or not to rebuild.

Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology President Bob Rich stated that “the scientific research community [is] deeply alarmed at the precedent set by the destruction of important, peer-reviewed research in the face of insufferable persecution. It is disturbing to learn that the pace of research discovery can be dictated by the destructive tactics of a group of extremists, rather than by the scientific community or the federal agencies charged with overseeing the care of animal subjects.” Frankie Tull, President of the Foundation for Biomedical Research, argued in a June 12, 2002 letter to NIH Director Elias Zerhouni that the long-term implications “of such valuable peer-reviewed research being abandoned as a result of unbearable harassment” were “frightening.” She wrote, “We fear that the loss of Dr. Podell and his research project is merely the beginning of an ever-increasing campaign against research discovery and medical advancement.”

University Arson Fire: The fire bombing of Dr. Michael Podell’s laboratory at OSU in 2001 caused extensive damage. OSU had employees and programs housed in the building

The ultimate goal of the eco- and animal rights terrorists is to use the threat of violence, including threats to human life and safety, to limit scholarly inquiry. The use of violence to further their goal should be abhorrent to all who are against the use of violence and especially to the entire academic community. If the research community is to protect itself from such terrorism, they will need to forge partnerships among themselves and with industry, their local communities, and federal and state governments. America’s global preeminence depends on its ability to conduct research. These terrorist groups threaten not only research, buildings, laboratories, and human lives; they threaten the United States of America.

Appendix 2: Non-Threatening Text

Education & Society/Security

Task Force on Eco- and Animal Rights Groups Finds State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges Lacking

One common thread that brings the institutions of the National Association of State Universities and Land-Grant Colleges (NASULGC) together is their collective involvement in promoting the interests of universities in the discovery of new knowledge. They are now faced with an unprecedented challenge to the traditional autonomy of the academy to educate, to discover, and to use new knowledge in service to their external communities. Eco- and animal rights activist groups seek to influence research (at universities and elsewhere) that relies on the use of animals, biotechnology, and genetically modified organisms that can be used to improve the human condition.

At its November 2001 Annual Meeting in Washington, D.C., the NASULGC Board of Directors formed a task force on eco- and animal rights activism to explore various issues related to such activism and to make recommendations to the NASULGC presidents. Several telephone conference meetings have been conducted over the last several months and a 2-day workshop in Washington, D.C. in June was convened to deal with the problem.

Increasing Eco- and Animal Rights Activism

The classic definition of activism is “a policy of vigorous action, especially in politics.” Today, successful activism has the potential of separating scientists from the university and ultimately scientists from their research careers.

The FBI has expressed concerns about the growing impact that eco- and animal rights activists may have on the university research community. The agency’s concerns include academicians’ management and security controls and the lack of tough federal laws that might deter eco- and animal rights activists.

While many university research facilities are located on large urban campuses and can be secured from activists, others are located in isolated areas that are far more difficult to secure. Moreover, the FBI believes, and we have confirmed, that faculty are worried about losing their research, often a life’s work, in attacks by domestic activist extremists. Faculty and university administrators have expressed concerns about the potential harm to facilities and laboratories worth hundreds of thousands of dollars. These concerns are heightened at land-grant universities with genetic research interests and rural agricultural research facilities.

Eco- and Animal Rights Groups on Campus

Eco- and animal rights activists have claimed credit for protests on university facilities across the United States, ranging from the burning of a University of California, Davis research facility nearly 20 years ago to the recent peaceful march on the University of Washington’s Center for Urban Horticulture. In the latter case, the fire damage to the university facility was estimated at $5.4 million. Property damage of other recent incidents includes:

-

Arsonists poured gasoline throughout the offices of researcher Catherine Ives, resulting in an estimated $900,000 in fire damage.

-

Windows, computers and laboratory equipment were ruined at one university’s poultry laboratory. The estimated cost of damage was $130,000.

-

A psychology laboratory was raided, offices trashed, acid poured on the floor, slogans painted on the walls and rats and rabbits removed from the laboratory. The cost of the clean-up was over $10,000.

Marching for Milk? Animal Rights activists protest what they consider to be inhumane treatment of cows during milking. The Dairy Farmers of America is a $1.2 billion industry that such protesters want to stop

Eco- and animal rights activists have also targeted numerous research facilities owned by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and private corporations that partner with universities in research activities. These groups’ influence on scientific research at all levels of the system is difficult to determine. What is clear, however, is that more than $3 million worth of property damage has been sustained. The loss of research is incalculable.

Education & Society/Security

The Story of Dr. Michael Podell

Since universities are the training ground for future generations of researchers, the loss of a single researcher and/or laboratory has far-reaching implications for the future of the research enterprise.

One recent case illustrates how activists can affect America’s experimental researchers. Until recently, Dr. Michael Podell of Ohio State University was one of the leading American HIV virus researchers. His research could provide important insights into how HIV and FIV penetrate the brain. His work was praised in peer-reviewed journals and was funded with a $1.68 million NIH grant.

Dr. Podell’s laboratory was picketed for several years by on-campus eco- and animal rights activists. Shortly after his office phone number and e-mail address were disclosed, Dr. Podell began receiving complaints about his work. Despite a USDA surprise visit to Ohio State University and Podell’s laboratory that found them in compliance with experimental animal policy, the complaints continued. Eventually, the university closed the lab out of liability concerns and Dr. Podell quit his profession as a researcher.

Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology President Bob Rich stated that “the scientific research community [is] deeply upset at the precedent set by the abandonment of important, peer-reviewed research in the face of such protests. It is troubling to learn that the pace of research discovery can be influenced by the tactics of a group of activists, rather than by the scientific community or the federal agencies charged with overseeing the care of animal subjects.” Frankie Tull, President of the Foundation for Biomedical Research, argued in a June 12, 2002 letter to NIH Director Elias Zerhouni that the long-term implications “of such valuable peer-reviewed research being abandoned as a result of these activists” were “difficult to imagine.” She wrote, “We think that the resignation of Dr. Podell represents a shift in the campaign against research discovery and medical advancement.”

Campaigners outside Sheffield University

The ultimate goal of the eco- and animal rights groups is to use activism to limit scholarly inquiry. The use of protests and other tactics to further their goal should be viewed cautiously by the entire academic community. In order to protect scientific research and university property, researchers will need to forge partnerships among themselves and with industry, their local communities, and federal and state governments. If they fail to do so, they will undermine the viability of their research and, thus, the ability to provide better opportunities for improved health and life for those they serve in America and elsewhere.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Suthammanont, C., Peterson, D.A.M., Owens, C.T. et al. Taking Threat Seriously: Prejudice, Principle, and Attitudes Toward Racial Policies. Polit Behav 32, 231–253 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-009-9102-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-009-9102-4