Abstract

Evidence has emerged demonstrating that whites no longer reject negative, explicit racial appeals as they had in the past. This seeming reversal of the traditional logic of the powerlessness of explicit appeals raises the question: Why are explicit racial appeals accepted sometimes but rejected at other times? Here, I test whether the relative acceptance of negative, explicit racial appeals depends on whites’ feelings of threat using a two-wave survey experiment that manipulates participants’ feelings of threat, and then examines their responses to an overtly racist political appeal. I find that when whites feel threatened, they are more willing to approve of and agree with a negative, explicit racial appeal disparaging African Americans—and express willingness to vote for the candidate who made the explicit racial appeal.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

In 2006, George Allen was running for reelection as a Senator of Virginia against Democrat Jim Webb. Allen was the clear front runner, but his lead started to crumble when, at a campaign rally, he called a Webb campaign volunteer of Indian descent “macaca” and welcomed him to America and “the real world of Virginia” (Craig and Shear 2006). Allen’s comment was broadly publicized as racist and, despite his attempts to backpedal, his support dropped by 16 points and he eventually lost the election (SurveyUSA 2006). Contrast this with any number of explicitly identity-based comments that Donald Trump made throughout his candidacy. He called Mexicans rapists, criminals, and drug dealers, promoted a “Muslim Ban,” and stated that African American youth “have no spirit” (Desjardins 2017). Yet, unlike Allen in 2006, Trump never apologized for these comments and despite, or perhaps because of, this explicitly negative rhetoric, he ultimately won the presidency in 2016.

Before the 2016 election, the predominant view among scholars was that we were in an era in which only subtle references to race were influential in shaping political attitudes, as overt references were thought to violate the dominant American “norm of equality” and as a result, be rejected by the public (Mendelberg 2001; Valentino et al. 2002). In order for racial appeals to be effective, they would have to be implicit rather than explicit (Hutchings and Jardina 2009). Trump’s success tells a very different story, especially considering many of his supporters like his personality and specifically the way he “speaks his mind,” more than his policy stances (Pew 2018). This seeming reversal of the traditional logic of the powerlessness of explicit appeals leads to the question: Why are explicit appeals tolerated sometimes but elicit backlash other times?

I test whether the relative acceptance of negative, explicit, racial appeals depends on the dominant group’s feelings of threat using a two-wave survey experiment that manipulates participants’ feelings of threat, and then examines their responses to an overtly racist political appeal. I find that when whites feel threatened, they are more accepting of an anti-African American explicit appeal. Feeling threatened is one mechanism behind the increased willingness of whites to approve of overtly racist language in political advertising. The recent increase in explicit racial rhetoric (Valentino et al. 2018b) and lack of backlash to such rhetoric (Valentino et al. 2018a) appears to be due, in part, to an increase in whites’ felt threat, and thus their tolerance for such appeals.

Implicit and Explicit Racial Appeals

Implicit and explicit appeals have largely been studied with regard to race and, specifically, anti-Black racism in America, as racial political appeals have long been a feature in American politics. Implicit racial appeals are subtle references to race, either verbally with coded language such as “welfare” or through the use of race-neutral language combined with racial imagery. Explicit racial appeals are references that directly mention race or a particular racial group with racial nouns, like “Black” or “race.” These appeals may be positive (complimentary towards the group they reference) or negative (derogatory towards the group they reference) (Mendelberg 2001; Valentino et al. 2002; Hutchings and Jardina 2009; Hutchings et al. 2010). For the purposes of this study, I focus exclusively on negative, explicit appeals—these are the types of appeals for which we have observed a shift in acceptability.

Negative, explicit racial appeals largely dominated American political discourse until the Civil Rights Movement brought about a new norm in American society that necessitated adherence to the principle of racial equality. After this, the power of implicit appeals emerged as explicitly racial rhetoric was no longer considered effective as it violated the now dominant “norm of equality” (Mendelberg 2001). Implicit appeals were still able to evoke race (and racial animus) to make it a salient consideration for candidate and policy evaluations, while simultaneously allowing respondents to deny that race is a factor in their decision-making (Valentino 1999; Mendelberg 2001; Valentino et al. 2002; Hurwitz and Peffley 2005; Hutchings and Jardina 2009; Banks and Bell 2013; Stephens-Dougan 2016).

The majority of studies on racial priming have found that implicit appeals are more effective than explicit appeals in eliciting racial considerations for judgments about candidates or policies. When these appeals become explicit, they lose their effectiveness as individuals abandon support for the policy or candidate because of its violation of the norm of equality, and shift their policy positions in a liberal direction (Mendelberg 2001; Valentino et al. 2002; Mendelberg 2008; Hutchings and Jardina 2009; Nteta et al. 2016). While there has been some evidence that explicit appeals can be effective at cuing racial considerations as well, under certain conditions or for certain individuals (Huber and Lapinski 2006; Hutchings et al. 2010), it is unclear whether this translates to approving of the overt racial rhetoric used. For example, Huber and Lapinski (2006) find that the explicit appeal is still outwardly rejected (with their measures, deemed “bad for democracy”), even when it exercises power over respondents’ decision making.Footnote 1

Most recently, Valentino et al. (2018a) find that racial attitudes predict policy attitudes and candidate evaluations—such as approval of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), Barack Obama, and Sarah Palin—irrespective of whether respondents are exposed to an implicit, explicit, or no racial appeal. Where it once took a subtle, implicit appeal to activate racial attitudes, now they appear to be activated by default. It bears emphasis that this pattern of results cannot be ascribed to obliviousness on the part of the survey respondents. Respondents readily identified racial content in the explicit but not the implicit condition, indicating that the treatment did work in the intended manner. Racial content was more obviously communicated in the explicit condition, but it was not rejected as it had been in the past (Valentino et al. 2018a). Clearly something has changed; whites are simply not as averse to negative explicit appeals as they used to be.

In a similar vein, Banks and Hicks (2019) find that exposing the racial content in an appeal (making the implicit appeal explicit) causes white racial liberals to withdraw their support, but not white racial conservatives. Even after racial content is explicitly identified, supporters remain (Banks and Hicks 2019). But, what has caused this change in the acceptance of negative explicit racial appeals? Possible causal mechanisms remain unclear.

Feeling Threatened

One potential contributor to the renewed effectiveness of explicit appeals may be the existence of a perceived threat to the dominant group. It could be that when whites feel that their group’s status at the top of the racial hierarchy is threatened, their prejudice activates. As a result, they may be more likely to endorse prejudiced language or rhetoric—like negative, explicit racial appeals directed at racial minorities. A threat seen as credible or imminent likely erodes any attempt at adherence to a norm of equality, as whites attempt to maintain their dominant position.

When there are perceived challenges to historically established hierarchies or positionings of groups, prejudice is activated as the dominant group seeks to retain its status (Blumer 1958; Bobo and Hutchings 1996; Quillian 1995; Huddy et al. 2005). Threat activates the expression of prejudice, rather than increases prejudice. While prejudice is difficult to change, the expression of that prejudice is often subject to group norms, which are more likely to be responsive to a perceived group threat (Paluck and Green 2009; Paluck 2009).

One key is that this threat is felt. This felt threat may be legitimate or illegitimate, material or symbolic. While this sense of threat may be connected to some kind of real or credible threat (Bobo 1988; Scheve and Slaughter 2001), it is not necessarily (Blumer 1958; Quillian 1995). A dominant group may be securely positioned in its status on the top of the hierarchy but still feel threatened. Further, this threat does not need to be material. Instead, the threat could be a more amorphous threat to a group’s status, rather than to its concrete economic wellbeing or cultural practices.

There are different implications for cognitively perceiving threat and emotionally feeling threat (Brader et al. 2008; Smith and Mackie 2008) as threats tend to evoke both anger and fear (Rhodes-Purdy et al. 2020). Generally, when people feel anxious, they are more open to new information, which can result in being open to invalid or false information as well (Marcus et al. 2000; Brader et al. 2008; Valentino et al. 2008). Brader et al. (2008) measure feeling threatened through the presence of anxiety, anger, and worry. They find that the development of these negative emotions after reading an article about immigration is more predictive of anti-immigration policy attitudes than the cognitive perception of such a threat. When respondents feel anxious, angry, or worried about the “threat” that immigration poses, they are more likely to support anti-immigration policies (Brader et al. 2008).

When members of a dominant group feel that their group’s status is threatened, they may be more willing to express prejudice against minorities as they seek to maintain their dominance. They may also, then, be more likely to approve of prejudiced rhetoric from politicians. I expect that such felt threat leads whites to approve of politicians who make overtly negative racial appeals.

Forms of Threat

Threat is a broad concept and can come from a variety of sources such as economic, cultural, political, or status concerns (Citrin et al. 1997; Kinder 2003; Sniderman et al. 2004; Kinder and Kam 2010). Here, I focus specifically on status threat, in which members of a group feel that their group’s dominant status, broadly conceived, is threatened.

When whites feel that their status as the majority racial group in the United States is in jeopardy, they are more likely to express their prejudice against all racial minorities (Craig and Richeson 2014a, b, 2018; Craig et al. 2018a, b). Craig et al. (2018a) find that increased status threat (to whites) results in greater expressions of racial bias against Latinxs, Blacks, and Asians, and a greater preference for their own racial group. Increased status threat also results in a shift toward the Republican Party (for unaffiliated white Americans) and a greater endorsement of conservative policy positions (Craig and Richeson 2014b). Further, Jardina (2019) finds that reminding whites of the impending majority–minority demographic shift in the U.S. makes white identifiers angry and fearful.

Today, whites are starting to perceive a greater threat from racial minority groups (Jardina 2019), as a result of a confluence of factors including economic stagnation (Knowles and Peng 2005), demographic shifts (Knowles and Peng 2005; Jardina 2019), and the symbolic threat that Barack Obama’s election as the first Black president of the United States posed to white political dominance (Kaiser et al. 2009; Effron et al. 2009; Valentino and Brader 2011; Jardina 2019). This environment is fertile ground for the reemergence of approval of explicit racial appeals, as whites feel more comfortable derogating racial minorities than they have in the recent past, due to an increase in feeling like their position at the top of the racial hierarchy is threatened.

I propose that feeling threatened is an important ingredient behind the varying acceptance of explicit racial appeals. When whites do not feel threatened, a norm of equality may dominate and they have no motivation to break with social desirability or social norms that dictate an adherence to egalitarianism. Under these circumstances, whites reject negative, explicit appeals about racial minority groups as they seek to uphold the norm of equality. However, feeling threatened exerts a cross-pressure, challenging the dominance of this norm. When individuals feel that their group is threatened by a political or social minority group, their prejudice activates and they focus on maintaining their dominant status. They are more willing to express prejudice against members of minority groups and, as such, likely more receptive to negative, explicit appeals directed at minority groups. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis

On average, white respondents who feel a heightened status threat will be more likely to approve of a negative, explicit racial appeal than those who do not.

Methods and Design

Measuring the effect of perceived threat on whites’ willingness to accept a negative, explicit racial appeal can be difficult to do observationally, as it is nearly impossible to determine causality with existing survey data. Nevertheless, it can provide a hint as to whether or not a link between these concepts exists. In an original analysis of data from the 2016 American National Election Study (ANES), I find that white respondents who feel that whites have too little influence in U.S. politics are also more likely to believe that people are too easily offended these days by the way that others speak (see Online Appendix G for the full analysis). This demonstrates that there is potentially a link between feeling threatened (i.e. believing that whites have too little influence) and accepting negative rhetoric (i.e. tolerance for potentially offensive language). Of course, there are shortcomings to this analysis. First, this link is not necessarily causal. Second, whites’ responses to explicit rhetoric in the abstract may not align with their willingness to approve of such language when it comes as a direct appeal from a politician, as racial appeals tend to be highly contextual.

As such, I designed a survey experiment to test the link between perceived threat and the acceptance of explicit appeals. Even in an experimental setting, untangling the relationship between racial attitudes, threat, and racial appeals can be difficult for several reasons. First, simply measuring racial attitudes may change how respondents later evaluate racial appeals. Second, isolating and inducing the feeling of threat can be problematic, as it is tied to real world events. If threat is already at its peak in the population, for example, then an experimental treatment intended to heighten it may do nothing—it is already at a ceiling.

To address these concerns, I designed a between-subjects, two-wave panel survey that was fielded by the firm Qualtrics on a nationally representative sample in the winter of 2018–2019.Footnote 2 In the first wave, I measure racial attitudes using the racial resentment scale. Measuring racial attitudes in the first wave ensures that these questions do not affect and are not affected by the experimental treatment conditions in wave two.

In the second wave of the survey, I attempt to manipulate feelings of status threat with stories of demographic change. The first treatment heightens threat, the second treatment reduces threat, and the third condition is a pure control. If threat is at a ceiling, this second treatment condition may still effectively produce variation in levels of threat by assuaging that threat. Respondents in the “status threat” condition read an article titled, “In a Generation, Racial Minorities May be the U.S. Majority.”Footnote 3 This article reports on the accelerating rate at which the nation’s racial minority population is growing. In the second treatment condition, the “status allay” condition, respondents read an article titled, “Racial Minorities No Longer Projected to be the U.S. Majority Any Time Soon.” This article (falsely) reports that the growth rate among white Americans is out-pacing that of racial minorities, and that the projection of an imminent majority-minority demographic change in the U.S. premature. Finally, respondents in the control condition read an article about the growing geographic mobility of people in the U.S. The full text of the three articles can be found in Online Appendix A, along with all question wording. After reading this article, the respondents were immediately asked to report their emotional reactions (whether the article made them feel anxious, proud, angry, hopeful, worried, or excited) on a 5-point scale from “none at all” to “extremely” (Watson et al. 1988; Brader et al. 2008).Footnote 4

Then, all respondents were exposed to a negative, explicit racial appeal. Their evaluations of this flyer serve as the dependent variables. The explicit appeal is a fabricated political flyer for a candidate that supposedly circulated during the 2018 Congressional midterm elections, pictured in Online Appendix A.Footnote 5 In the flyer, there is a picture of African Americans protesting. The flyer claims that, “Welfare and food stamps are already bleeding taxpayers dry” and, alongside a picture of African Americans protesting, asks, “And now, they want MORE?” There is a quote that follows from the candidate which reads: “This new tax bill is just a giveback to African American voters and groups like ACORN and the NAACP who got them elected. It’s Big Government forcing us to pay reparations for slavery, and it has got to end.” The flyer concludes by urging voters to “Stop the Handouts.”

This is an explicit appeal because it overtly mentions “African Americans.” As such, the reference to race by the candidate is undeniable. It is a negative, anti-African American appeal because it cues negative stereotypes about African Americans. It characterizes African Americans as welfare dependent and undeserving. It contrasts them with “taxpayers” who are said to be bled dry by this government assistance to African Americans. Further, it depicts African Americans as intimidating and demanding, depicting them as ungrateful for the excess of government assistance that they supposedly already receive. These characterizations evoke longstanding, negative stereotypes about African Americans in the U.S. context: welfare dependent, undeserving, and entitled (Gilens 2009; Harris-Perry 2011; Dixon 2008; Neubeck and Cazenave 2002). The flyer itself is explicitly racist and thus, a high bar for whites to come to accept.

After exposure to the appeal, respondents are asked to evaluate the flyer on several dimensions. The questions were asked in the following order (below) and respondents were not able to go back and change their answers to any questions. The flyer was pictured above each question. The questions intentionally move from general to specific—and from no racial content to asking about the racial content specifically. The questions were presented in this order to measure respondents’ initial reaction to the flyer as a whole before priming their racial attitudes by asking questions that evoke race. The expectation is that those respondents who felt threatened will react more positively to the flyer and the claims that it makes. The questions asked:

-

1.

Do you think the flyer makes a fair point?

-

2.

If he was running in your district, how likely is it that you would support this candidate, Jacob Miller, for office?

-

3.

Are you offended by the claims made in the flyer?

-

4.

How racially insensitive is the flyer, in your opinion?

-

5.

Do you agree or disagree with the flyer’s claim that government handouts to African Americans need to be decreased?

Each question measures a different dimension of the “acceptability” of the flyer. The first question measures respondents’ general reactions to the flyer and gets at the normative acceptability of these kinds of claims. Whether or not you agree with the explicit appeal, is this an okay position to hold? The second question is more straight forward: it measures willingness to vote for this candidate. The third question measures backlash against the flyer. The fourth question measures the extent to which respondents identify hostile racial content in the flyer. Finally, the last item is a measure of respondents’ level of agreement with the racial stereotype articulated by the flyer.

One question that may arise is why there is no implicit racial appeal in this study, as this differs from most studies of racial priming. This study evaluates the antecedents to approval of an explicit appeal, as this is the shift that has occurred: whites used to reject explicit appeals, but now they do not (Valentino et al. 2018a). As such, evaluations of an explicit appeal are the key dependent variables. The heightened level of threat is the treatment. It is designed this way in order to evaluate what leads to approving of an explicit appeal; to better understand the causal mechanism behind approving of an explicit appeal. Hutchings et al. (2010) similarly only include explicit appeals as they seek to evaluate when explicit appeals, specifically, can be effective. The recent shift that this study seeks to understand is whites’ increased tolerance for explicit racial rhetoric.

Overall, I expect that respondents exposed to the heightened status threat condition to be more approving of the racist flyer. They will be more likely to say it makes a fair point, that they would vote for the candidate who put it out, and that they agree with the claims made in the flyer. They should be less likely to say that the flyer is offensive or insensitive, as I expect that they will have a greater tolerance for the explicit appeal.

Analyses and Results

Before getting to the results, power and balance analyses demonstrate that the survey is sufficiently powered and that its randomization was successful. A manipulation check on the treatment demonstrates that the respondents clearly understood and retained the information provided in each treatment. Those in the status threat condition were more likely to agree with the statment that “racial minorities are likely to reduce the influence of white Americans in society very soon” and those in the status allay condition were more likely to disagree with the statement.

While respondents’ cognitive perceptions of threat were shifted by the treatments, their emotional responses to the two treatments were similar. In terms of felt threat, as measured by the development of negative emotions (following Brader et al. 2008), the status threat treatment condition did made respondents feel significantly more anxious, angry, and worried (i.e. more threatened) than the control condition, as expected. However, the the status allay treatment condition did not make respondents significantly less anxious, angry, or worried than the control. In a sense, it seems that the status allay condition, merely by bringing up demographic change (even though it reported that it was slowing), cued a small amount of felt threat.Footnote 6 For this reason, and because this study theorizes about heightened status threat, it focuses its tests on the status threat condition.

Respondents were recruited to match national averages on gender, age, education, income, race (though I restrict my analyses to white, non-Latinx respondents). In this sample, the mean level of education lies between some college and a two-year/Associate’s degree, which is comparable to the national average among white Americans (1 year of college). The mean age is 52, comparable to the national average for adult whites which is 49 and the mean household income is between between $40,000 and $59,999, which is slightly lower than the average for whites (which is about $65,902).Footnote 7 The sample is slightly skewed toward female respondents, as it is comprised of 259 males and 389 females. In terms of partisanship and political ideology, the mean respondent is Independent and moderate or middle of the road, which mirrors that of the weighted 2018 CCES mean response among whites.

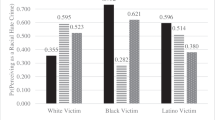

Turning to the analyses, I first calculate the average treatment effects for each of the five dependent variables. In order to do so, I estimate a series of OLS regressions that predict the dependent variable with the treatment condition indicator. The models are presented in Online Appendix C and the coefficients on the heightened status threat treatment condition (compared to the control) are plotted in Fig. 1. In the whole sample, the heightened status threat treatment condition has no statistically significant effect on the dependent variables, though the coefficient for the “fair point” model is positive.

There could be several explanations for these null results. First, it could be that the treatment truly had no effect on the outcome of interest. Second, it could be that the explicit appeal itself ignited threat among respondents, washing out any threat effect of the initial treatment. I can test this possibility because respondents were asked to report their emotional reactions to the explicit appeal immediately after viewing it (using the same battery they saw after the treatment (Watson et al. 1988; Brader et al. 2008)). Indeed, all respondents reported feeling more anxious, angry, and worried (emotional indicators of threat) after seeing this flyer than proud, hopeful, or excited (analyses reported in Online Appendix B.7). There are no significant differences between the emotional responses of those in the status threat condition and those in the control condition. This indicates that the explicit appeal itself triggered threat among respondents and thus, may have washed out treatment effects from the demographic change article.

A third possible explanation for these null treatment effects, that is not divorced from the second explanation, is that the news story about demographic change did not uniformly threaten the white respondents who read it. While this analysis estimates total treatment effects, it cannot capture the effect of the treatment that hinges on respondents actually becoming threatened. Recall that the expectation laid out with respect to threat relies on respondents in the status threat treatment condition actually developing feelings of threat. This is not necessarily a given. The treatment condition itself is a dry and straightforward news story about the growing majority–minority population. It reports on this fact in a neutral way and does not attempt to elicit feelings of threat with emotional language. Instead, it is simply the presentation of a demographic fact. Respondents can take that fact however they choose.

In order to understand whether respondents were truly threatened by the treatment, I turn to their reported emotional reaction to the news story they read. In my research design, I included one question separating the treatment from the dependent variables: a measure of emotions. I anticipated that the respondent’s emotional reaction to the treatment may be more deterministic of their approval of the explicit appeal than their cognitive reaction—as was the case in Brader, Valentino, and Suhay’s (2008) analysis of the production of anti-immigration sentiment. This question measures the potential mediator (feeling threatened) between the treatment and the dependent variable. Acceptance of the explicit appeal may depend on respondents becoming threatened, represented in Fig. 2.

In this model, respondents read the article about changing demographics (the treatment) and then some of them become threatened. For the respondents who do become threatened, they are more willing to approve of a negative explicit racial appeal. This sequence characterizes a mediating relationship. The treatment changes the level of threat that a respondent feels (the mediator), which in turn affects their evaluation of the explicit appeal (the outcome). I operationalize the mediator, felt threat, as the production of negative emotions (anxiety, anger, and worry) because this reaction indicates that the respondent is bothered by changing demographics in the U.S. Take the production of anxiety, for example, Fig. 3a demonstrates that individuals did develop more anxiety in the status threat condition, compared to the control. But, within the status threat condition, Fig. 3b and c demonstrate that anxiety was not evenly distributed. People with higher levels of racial resentment and Republicans were more likely to become anxious.Footnote 8 While the status threat treatment condition did evoke more anxiety overall, there were individual-level characteristics that determined the extent to which individuals developed that anxiety. The distributions of anger and worry follow a similar pattern to those presented in Fig. 3.

These distributions suggest that there may be a variety of pre-treatment covariates that determine the level of threat that the treatment induces in the respondent. In order to get at what happens once a respondent becomes threatened, I rely on a mediation model developed by Imai et al. (2011). While mediation has historically been difficult to establish (Bullock et al. 2010), the Imai et al. (2011) model allows for the unbiased estimation of causal mediation effects with no assumptions about the distributional or functional form of the models used.Footnote 9

I specify sets of mediation models for each emotion measured. I expect that anxiety, worry, and anger (i.e. feeling threatened) will have significant, positive effects on approval of the explicit appeal. That is, an increase in anxiety, worry, and anger will lead to greater approval of the flyer. I do not expect that any positive emotions (i.e. pride, hope, or excitement) will mediate this relationship, as theoretically, feeling threatened should be the mechanism, not feeling good.

The average causal mediation effect (ACME) is the effect of the treatment on the dependent variable, due to its effect on the mediator (Imai et al. 2011).Footnote 10 This statistic can be interpreted even when there is not a statistically significant total effect (Shrout and Bolger 2002; Hayes 2009; Zhao et al. 2010; Rucker et al. 2011; Kenny and Judd 2014; O’Rourke and MacKinnon 2015), with attention to sensitivity analyses (Loeys et al. 2015). In the first set of mediation models that I specify with anxiety as the mediator, it is the average effect that the heightened status threat treatment had on evaluations of the racist flyer that is attributable to its influence on the respondent’s level of anxiety (one measure of their felt threat).

I specify sets of mediation models for each potential emotional reaction to the treatment article: anxiety, anger, worry, pride, hope, and excitement. I also specify a model for a felt threat scale that combines anxiety, anger, and worry due to their strong relationships to one another in this sample (\(\alpha = 0.89\)) and following Brader, Valentino, and Suhay’s (2008) operationalization of threat. Separate mediation models are specified for each measure of the respondent’s evaluation of the racist flyer. I expect that developing negative emotions after reading the article about demographic change will lead to more agreement that the flyer makes a fair point, that they would vote for the candidate who put the flyer out, and that they agree with claims made about African Americans in the flyer—and to less agreement that the flyer is offensive or racially insensitive. I also expect that positive emotions (pride, hope, and excitement) will have no effect on evaluations of the flyer. The average causal mediation effects produced from these mediation models are presented in Table 1 and the full mediation models are presented in Online Appendix C.

First, examine the average causal mediation effects attributable to the production of negative emotions. When the respondent becomes anxious, angry, or worried, they become more willing to agree that the flyer makes a fair point, that they would vote for the candidate who put the flyer out, and that they agree with claims made about African Americans in the flyer. There are no statistically significant effects on being offended by the flyer or believing that it is racially insensitive. Threat seems to motivate individuals to agree with the flyer, but not significantly depress any backlash to it. As the development of anxiety, anger, and worry are closely related in this survey (between the three, \(\alpha = 0.89\)), it is impossible to disentangle effects attributable to one specific emotion with this sample. Nevertheless, there is a clear, statistically significant and substantively meaningful effect on approving of the explicit appeal when the respondent develops negative emotions after reading an article about demographic change.

The difference that results from the development of negative or positive emotions is stark. Models that specify positive emotions as the mediators make it clear that it is not simply emotional arousal that leads to agreement with this flyer, as they do not replicate effects produced by negative emotions. While there are positive and statistically significant effects for saying that the flyer makes a fair point in the pride and excitement models, the magnitudes of these effects are close to zero (pride = 0.06 and excitement = 0.05), and are tiny in comparison to the effects observed for the development of negative emotions (e.g. ranging from 0.16 to 0.25). Further, these effects only exist for one of the five dependent variables whereas the effects borne out of the development of negative emotions consistently pervade all of the models that measure approval of the flyer.

The coefficients on the mediation effects for the models specified with the felt threat scale as the mediator are plotted in Fig. 4. These estimates are the differences between the value of the outcome predicted under the status threat condition using the level of felt threat predicted under this condition (i.e. higher threat) and the value of the outcome predicted under the status threat condition using the level of felt threat predicted under the control condition (i.e. lower threat). They are the effects of heightened felt threat (i.e. more anxiety, anger, and worry) in the treatment condition. Respondents in the status threat treatment condition who became anxious, angry, and worried are more likely to say that the flyer made a fair point, that they would vote for the candidate who put out the racist flyer, and that they agree with the claims made in the flyer about African Americans.

The average causal mediation effects can be interpreted similarly to OLS coefficients. In the status threat treatment condition, a one unit increase in felt threat (on a 5-point scale) leads to a 0.23 point increase in agreeing that the flyer made a fair point (on a 5-point scale). The same increase in felt threat also led to a 0.25 increase in willingness to vote for the candidate who put out the racist flyer (on a 6-point scale) and a 0.20 increase in agreement with the flyer’s claim that African Americans receive too many handouts from the government (on a 7-point scale). This is all to say: respondents who become anxious, angry, and worried (who feel threatened) after reading about the growing majority–minority population, are more approving of the explicit, anti-African American appeal.

Note that the effect on whether or not the respondent agrees with the flyer remains even after respondents were asked whether or not they thought the flyer was racially insensitive or offensive. These slightly leading questions amount to “calling out” the flyer by identifying its racial content and making some suggestion that it could be insensitive or offensive. Nevertheless, even after these questions, respondents in the treatment condition who felt threatened were still willing to agree with the most overtly racial dependent variable: they were willing to endorse the stereotype that African Americans get too many handouts from the government.

In the heightened status threat condition, respondents who felt threatened were more likely to approve of the explicit racial appeal and the politician who made it. While this study demonstrates a causal link between feeling threatened and approving of an explicit racial appeal, the effect sizes themselves are fairly small. Nevertheless, this is a conservative test. The “threatening” treatment is tame compared to real world media coverage or political rhetoric. This treatment merely reports on changing demographics in a scientific and straightforward way. Contrast this with media narratives that often warn of violence, invasion, and attack (Garber 2020). Further, while the treatment in this experiment is fairly mild, the explicit appeal itself is not. This flyer is recognizably stereotypical and racist in its direct indictment of African Americans—both verbally and visually. Recent works in progress demonstrate that people are less willing to accept explicit appeals directed at African Americans than at other minority groups (Arora 2019). Thus, approving of this flyer at all is quite a hurdle.

Finally, it should be noted that the status threat article induced threat by reporting that the minority population was growing and the white population was shrinking. The article did not single out African Americans as the cause of this change. If anything, the notion of “majority minority” often evokes the Latinx community and growing immigrant populations. Nevertheless, whites who felt threatened by this story were more likely to approve of a racist flyer specifically directed at African Americans—a group that is not stereotypically associated with demographic change. This is in line with findings from Craig and Richeson (2014a) who demonstrate that increased status threat leads to increased racial animosity against all minority groups, not solely the group who is purportedly posing the threat.

Subgroup Analyses

To investigate whether some white respondents are more sensitive to this particular form of status threat, demographic change, the analyses were repeated for two sets of subgroups: by partisanship, and by racial resentment level. Mediation models are specified using the felt threat mediator (scale of anxiety, anger, and worry) and are presented in Online Appendix C.10. Indeed, subgroup differences do appear. Republicans (and those who lean Republican) who become threatened after reading about demographic change are more likely to state that the explicit appeal made a fair point (\(\beta = 0.30\), \(\hbox {p} = 0.00\)), that they would vote for the politician who put out the advertisement (\(\beta = 0.35\), \(\hbox {p} = 0.00\)), and that they agree with the claims made about African Americans (\(\beta = 0.23\), \(\hbox {p} = 0.05\)). There are no significant results for Democratic respondents.

This could mean that white Democrats are simply less likely to experience (or express) racial status threat—but it could also mean that this specific form of status threat (demographic change) is not one that is particularly bothersome to white Democrats. Perhaps increasing demographic change makes white Democrats think about increasing electoral victories, as racial minorities tend to vote in higher margins for the Democratic Party. This would not mean that white Democrats could never experience racial status threat—but instead, that this particular operationalization of racial status threat is not threatening to them. Future work should examine partisan-specific forms of racial threat to better understand the conditions under which white Democrats do feel threatened, and the consequences of that felt threat.

Similarly, there are no significant results for whites with lower racial resentment scores (below 0.42 on a 0-1 scale, N = 117). However, respondents in the medium resentment (above 0.42 but below 0.70; N = 139) category who become threatened after reading the article about demographic change are more likely to say that the flyer makes a fair point (\(\beta = 0.23\), \(\hbox {p} = 0.01\)), that they would vote for the candidate who put out the flyer (\(\beta = 0.29\), \(\hbox {p} = 0.00\)), and that they agree with claims made about African Americans in the flyer (\(\beta = 0.20\), \(\hbox {p} = 0.03\)). The magnitude only grows for respondents with higher levels of racial resentment (greater than or equal to 0.70; \(\hbox {N} = 146\)). Respondents in the higher resentment category who become threatened after reading the article about demographic change are more likely to say that the flyer makes a fair point (\(\beta =0.32\), \(\hbox {p} = 0.01\)), that they would vote for the candidate who put out the flyer (\(\beta = 0.39\), \(\hbox {p} = 0.01\)), and that they agree with claims made about African Americans in the flyer (\(\beta = 0.39\), \(\hbox {p} = 0.05\)).

This makes sense, as white respondents with higher levels of resentment are likely most bothered by the notion that their racial group will soon be displaced as the majority. Again, this could mean that whites with lower levels of racial resentment do not experience racial threat. However, a more likely explanation may be that those particular whites are not sensitive to demographic change as a threat. In the future, work should examine the way that different forms of racial threat could elicit reactions among whites with lower levels of racial resentment.

Limitations

This study finds that the development of anxiety, anger, and worry after exposure to a racial status threat leads whites to approve of an explicit racial appeal. In this sample and with this measure of emotions,Footnote 11 the high degree of correlation between anger, anxiety, and worryFootnote 12 prevents disentangling effects that may be due specifically to anxiety, say, as opposed to anger—which are distinct emotions that are known to have politically disparate effects (Best and Krueger 2011; Valentino et al. 2011; Albertson and Gadarian 2015; Phoenix 2019). Future work could start to uncover when threat cues distinct emotions, and the consequences on accepting explicit appeals that these emotions may have. Here, I am only able to point to a broad range of felt threat (anxiety, anger, and worry) that produces support for derogations of racial minorities.

Further, this study tackles when whites approve of explicit appeals and does not speak to their approval of implicit appeals, as the recent shift has been in whites’ increased tolerance for explicit appeals. Understanding when whites accept explicit appeals is a harder test, as whites who approve of explicit appeals would almost certainly approve of subtler, more discrete, implicit appeals. However, it could be fruitful to measure the likely more pronounced effects that felt threat would have on accepting subtler, implicit appeals. This study presumably underestimates the role of felt threat in producing support for racist rhetoric and the politicians who disparage racial minorities, compared to what is witnessed in U.S. politics today.

Finally, the findings presented in the body of this manuscript center on one sample. However, another survey experiment fielded in the summer of 2019, presented in Online Appendix H, replicates these results, finding that the development of negative emotions after reading an article about the cultural implications of the changing demographics of the U.S. leads to an increased approval of a similar explicit racial appeal. This second experiment has some shortfalls in design (e.g. not a two wave study) and implementation (e.g. group imbalances). Nevertheless, the results from this second experiment suggest that the findings presented in the body of this manuscript are not confined to one sample. Further, both of these experiments corroborate findings from a 2016 ANES analysis demonstrating that there is an observational link between felt threat and approval of potentially offensive language (see Online Appendix G). This ANES analysis lends external validity to the study presented here.

Discussion

The prevalence and effectiveness of explicit racial rhetoric ebbs and flows; appeals seem to be tolerated at some moments more than others. This study tests one causal mechanism by which whites come to tolerate a negative, explicit racial appeal: status threat. When whites feel threatened, they are more likely to approve of racist language disparaging African Americans—and they are more willing to vote for a politician who uses such language. The key dependent variables in this study are evaluations of an explicitly racist flyer—it is a high bar for whites to accept these claims, and troubling that they come to.

It bears emphasis that the article that threatened white respondents in this study reported accurate statistics and paralleled real news coverage. The experiment is naturalistic in the sense that white Americans really are being exposed to these messages. The U.S. population is becoming less white, rapidly. To many whites, this fact represents a status threat and when they are reminded of their impending minority status, they retaliate against racial minorities. One important caveat that this study makes clear is that some whites experience demographic change as a racial status threat to a greater degree than others. Future work should examine the particular forms of racial status threat that do bother white Democrats and whites with lower racial resentment to better understand the implications of racial status threat for all whites.

When George Allen’s 2006 campaign suffered for his racist comment, this threat likely felt further away and less pressing to many whites. Thirteen years later—with the election of the first Black president (Kaiser et al. 2009; Valentino and Brader 2011; Effron et al. 2009), economic stagnation (Knowles and Peng 2005), and soon-to-be demographic minority status (Knowles and Peng 2005; Jardina 2019)—status threat is now a salient concern for many more whites. Indeed, the experimental manipulation in this study demonstrates that any mention of demographic change appears to cue some degree of felt threat among whites. This may indicate that whites are particularly sensitive to demographic threat, even when it is presented as mild and far off, in our current moment.

Explicit racial rhetoric in contemporary politics is not confined to the United States. Across the world, overt, negative references to racial and identity minorities by politicians appear to be increasing. Jair Bolsonaro, the man elected as President of Brazil in 2018, has referred to black activists as “animals” (Forrest 2018) and the leader of Hungary’s conservative party has characterized refugees as “Muslim invaders” (Pearson 2018). In the U.S., the frequency of overt racial references has been steadily increasing since the election of the first Black president, Barack Obama (Valentino et al. 2018b).

This change in the acceptability of explicit rhetoric is concerning. Not only can racist language—whether it is implicit or explicit—be harmful to members of the groups that it stigmatizes on a discursive level (Matsuda 1989; Lawrence 1990), there is also a connection between racist language and racist action, like hate crimes (Edwards and Rushin 2018; Müller and Schwarz 2018), and between racism and concrete outcomes in realms like health and education (Paradies 2006; Marx 2006). An increase in racist language, which is at least partially due to whites’ increased willingness to approve of it, hurts members of the groups that it stigmatizes.

This study makes clear that one causal mechanism behind whites’ increased acceptance of explicit racial appeals is feeling threatened. Of course, this is likely not the sole cause for the variation in the acceptance of explicit racial appeals. It is possible that there are many other factors that contribute to the acceptance (or rejection) of explicit racial language. Successful social movements, like the Civil Rights Movement, for example, are mechanisms by which the norm of racial equality is strengthened, which leads whites to reject negative, explicit rhetoric. From this analysis, it is clear that racial status threat is one piece of the puzzle, but there is still much more to investigate.

Notes

Part of a larger, multi-investigator survey (Hetherington et al. 2018). The first wave was fielded from November 27, 2018 to December 20, 2018 and the second wave was fielded from January 22 to February 7, 2019.

Modeled off Craig and Richeson's (2018) treatment.

Because the item asks about the news article and does not directly ask for their attitudes about demographic change, self-monitoring effects are relatively unlikely.

Some of the language used in this flyer was adapted from the language in one of Valentino, Neuner, and Vandenbroek’s (2018a)’s explicit racial appeals. In their work, this language is part of a news story about the Affordable Care Act.

All power, balance, and manipulation tests presented in Online Appendix B, along with descriptive statistics of key variables and the demographic and ideological features of the sample.

2018 ACS Estimates obtained from IPUMS USA, University of Minnesota, www.ipums.org (Ruggles et al. 2020).

Note that this is not simply a feature of people who are higher in racial resentment or Republicans. In the control condition, there were almost no differences in anxiety development. See Online Appendix B.

However, it does require the assumption of sequential ignorability—I address this assumption by (1) random assignment of treatment and (2) inclusion of potential confounders like racial resentment. See Online Appendix B for greater discussion of this assumption, the mediation model, and for sensitivity tests.

See Online Appendix B for greater discussion of how this statistic is obtained.

Regression-based mediation models similarly reveal significant effects at various times for anxiety, anger, and worry. See Online Appendix C.9 for more detail, and supplemental analyses of subgroup analyses in Online Appendix C.10.

Anxiety and anger correlate at 0.70; anxiety and worry correlate at 0.78; and anger and worry correlate at 0.74.

References

Albertson, B., & Gadarian, S. K. (2015). Anxious politics: Democratic citizenship in a threatening world. Cambridge University Press.

Arora, M. (2019). Which race card? Understanding racial appeals in U.S. politics. Doctoral Dissertation, UC Irvine. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9f46x25t.

Banks, A. J., & Bell, M. A. (2013). Racialized campaign ads: The emotional content in implicit racial appeals primes White racial attitudes. Public Opinion Quarterly, 77(2), 549–560. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nft010.

Banks, A. J., & Hicks, H. M. (2019). The effectiveness of a racialized counterstrategy. American Journal of Political Science, 63(2), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12410.

Best, S. J., & Krueger, B. S. (2011). Government monitoring and political participation in the United States: The distinct roles of anger and anxiety. American Politics Research, 39(1), 85–117. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X10380848.

Blumer, H. (1958). Race prejudice as a sense of group position. Pacific Sociological Review, 1(1), 3–7. https://doi.org/10.2307/1388607.

Bobo, L. (1988). Group conflict, prejudice, and the paradox of contemporary racial attitudes. In P. A. Katz & D. A. Taylor (Eds.), Eliminating racism (pp. 85–114). New York: Springer.

Bobo, L., & Hutchings, V. L. (1996). Perceptions of racial group competition: Extending Blumer’s theory of group position to a multiracial social context. American Sociological Review, 61(6), 951–972. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096302.

Brader, T., Valentino, N. A., & Suhay, E. (2008). What triggers public opposition to immigration? Anxiety, group cues, and immigration threat. American Journal of Political Science, 52(4), 959–978. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2008.00353.x.

Bullock, J. G., Green, D. P., & Ha, S. E. (2010). Yes, but what’s the mechanism? (don’t expect an easy answer). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98(4), 550–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018933.

Citrin, J., Green, D. P., Muste, C., & Wong, C. (1997). Public opinion toward immigration reform: The role of economic motivations. The Journal of Politics, 59(3), 858–881. https://doi.org/10.2307/2998640.

Craig, M. A., & Richeson, J. A. (2014a). More diverse yet less tolerant? How the increasingly diverse racial landscape affects White Americans’ racial attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 40(6), 750–761. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167214524993.

Craig, M. A., & Richeson, J. A. (2014b). On the precipice of a “majority–minority” America: Perceived status threat from the racial demographic shift affects white Americans’ political ideology. Psychological Science, 25(6), 1189–1197. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797614527113.

Craig, M. A., & Richeson, J. A. (2018). Hispanic population growth engenders conservative shift among non-Hispanic racial minorities. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(4), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617712029.

Craig, M. A., Rucker, J. M., & Richeson, J. A. (2018a). The pitfalls and promise of increasing racial diversity: Threat, contact, and race relations in the 21st century. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(3), 188–193. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721417727860.

Craig, M. A., Rucker, J. M., & Richeson, J. A. (2018b). Racial and political dynamics of an approaching “majority–minority” United States. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 677(1), 204–214. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716218766269.

Craig, T., & Shear, M. D. (2006). Allen quip provokes outrage, apology. The Washington Post, Retrieved July 20, 2018 from https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/2006/08/15/allen-quip-provokes-outrage-apology-span-classbankheadname-insults-webb-volunteerspan/64f96498-cdfc-48f3-ade6-bcd8a4ea7514/

Desjardins, L. (2017). Every moment in Trump’s charged relationship with race. PBS News Hour. Retrieved July 20, 2018 from https://www.pbs.org/newshour/politics/every-moment-donald-trumps-long-complicated-history-race.

Dixon, T. L. (2008). Network news and racial beliefs: Exploring the connection between national television news exposure and stereotypical perceptions of African Americans. Journal of Communication, 58(2), 321–337. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00387.x.

Edwards, G. S., & Rushin, S. (2018). The effect of president Trump’s election on hate crimes. Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3102652.

Effron, D. A., Cameron, J. S., & Monin, B. (2009). Endorsing Obama licenses favoring whites. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(3), 590–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.02.001.

Forrest, A. (2018). Jair Bolsonaro: The worst quotes from Brazil’s far-right presidential frontrunner. The Independent. Retrieved February 12, 2020, from https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/jair-bolsonaro-who-quotes-brazil-president-election-run-latest-a8573901.html.

Garber, M. (2020). Do you speak Fox? How Donald Trump’s favorite news source became a language. The Atlantic. Retrieved September 16, 2020, from https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2020/09/fox-news-trump-language-stelter-hoax/616309/

Gilens, M. (2009). Why Americans hate welfare: Race, media, and the politics of antipoverty policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Harris-Perry, M. V. (2011). Sister citizen: Shame, stereotypes, and Black women in America. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Communication Monographs, 76(4), 408–420. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637750903310360.

Hetherington, M., Conover, P., Aziz, A., Christiani, L., McDonald, M., & Treul, S. (2018). Survey data collection: Public attitudes in the 2018 election. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, UNC IRB 18-2732.

Huber, G. A., & Lapinski, J. S. (2006). The “race card” revisited: Assessing racial priming in policy contests. American Journal of Political Science, 50(2), 421–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2006.00192.x.

Huddy, L., Feldman, S., Taber, C., & Lahav, G. (2005). Threat, anxiety, and support of antiterrorism policies. American Journal of Political Science, 49(3), 593–608. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2005.00144.x.

Hurwitz, J., & Peffley, M. (2005). Playing the race card in the post-willie Horton era: The impact of racialized code words on support for punitive crime policy. Public Opinion Quarterly, 69(1), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfi004.

Hutchings, V. L., & Jardina, A. E. (2009). Experiments on racial priming in political campaigns. Annual Review of Political Science, 12, 397–402. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.polisci.12.060107.154208.

Hutchings, V. L., Walton, H, Jr., & Benjamin, A. (2010). The impact of explicit racial cues on gender differences in support for confederate symbols and partisanship. The Journal of Politics, 72(4), 1175–1188. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381610000605.

Imai, K., Keele, L., Tingley, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2011). Unpacking the black box of causality: Learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. American Political Science Review, 105(4), 765–789. https://doi.org/10.2307/23275352 .

Jardina, A. (2019). White Identity Politics. Cambridge University Press.

Kaiser, C. R., Drury, B. J., Spalding, K. E., Cheryan, S., & O’Brien, L. T. (2009). The ironic consequences of Obama’s election: Decreased support for social justice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(3), 556–559. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.01.006.

Kenny, D. A., & Judd, C. M. (2014). Power anomalies in testing mediation. Psychological Science, 25(2), 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613502676.

Kinder, D. R. (2003). Belief systems after converse. In M. MacKuen & G. Rabinowitz (Eds.), Electoral Democracy (pp. 13–47). University of Michigan Press.

Kinder, D. R., & Kam, C. D. (2010). Us against them: Ethnocentric foundations of American opinion. University of Chicago Press.

Knowles, E. D., & Peng, K. (2005). White selves: Conceptualizing and measuring a dominant-group identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 89(2), 223–241. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.89.2.223.

Lawrence, C. R. (1990). If he hollers let him go: Regulating racist speech on campus. Duke Law Journal, 1990(3), 431–483. https://doi.org/10.2307/1372554.

Loeys, T., Moerkerke, B., & Vansteelandt, S. (2015). A cautionary note on the power of the test for the indirect effect in mediation analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1549. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01549.

Marcus, G. E., Neuman, W. R., & MacKuen, M. (2000). Affective intelligence and political judgment. University of Chicago Press.

Marx, S. (2006). Revealing the invisible: Confronting passive racism in teacher education. London: Routledge.

Matsuda, M. J. (1989). Public response to racist speech: Considering the victim’s story. Michigan Law Review, 87(8), 2320–2381. https://doi.org/10.2307/1289306.

Mendelberg, T. (2001). The race card: Campaign strategy, implicit messages, and the norm of equality. Princeton University Press.

Mendelberg, T. (2008). Racial priming revived. Perspectives on Politics, 6(1), 109–123.

Müller, K., & Schwarz, C. (2018). From hashtag to hate crime: Twitter and anti-minority sentiment. (March 30, 2018) Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3149103

Neubeck, K. J., & Cazenave, N. A. (2002). Welfare racism: Playing the race card against America’s poor. London: Routledge.

Nteta, T. M., Lisi, R., & Tarsi, M. R. (2016). Rendering the implicit explicit: Political advertisements, partisan cues, race, and white public opinion in the 2012 presidential election. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 4(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/21565503.2015.1050407.

O’Rourke, H. P., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2015). When the test of mediation is more powerful than the test of the total effect. Behavior Research Methods, 47(2), 424–442. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-014-0481-z.

Paluck, E. L. (2009). Reducing intergroup prejudice and conflict using the media: A field experiment in Rwanda. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(3), 574–587. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0011989.

Paluck, E. L., & Green, D. P. (2009). Prejudice reduction: What works? A review and assessment of research and practice. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 339–367. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163607.

Paradies, Y. (2006). A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. International Journal of Epidemiology, 35(4), 888–901. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyl056.

Pearson, A. (2018). Viktor orban’s most controversial migration comments. DW (2018). Retrieved 12 February 2020 from: https://www.dw.com/en/viktor-orbans-most-controversial-migration-comments/g-42086054.

Pew. (2018). Trump has met the public’s modest expectations for his presidency. Washington: Pew Research Center. Retrieved July 20, 2018 from https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2018/08/23/trump-has-met-the-publics-modest-expectations-for-his-presidency/.

Phoenix, D. L. (2019). The Anger Gap: How Race Shapes Emotion in Politics. Cambridge University Press.

Quillian, L. (1995). Prejudice as a response to perceived group threat: Population composition and anti-immigrant and racial prejudice in Europe. American Sociological Review, 60(4), 586–611. https://doi.org/10.2307/2096296.

Rhodes-Purdy, M., Navarre, R., & Utych, S. M. (2020). Measuring simultaneous emotions: Existing problems and a new way forward. Journal of Experimental Political Science, First View, 1–14, https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2019.35.

Rucker, D. D., Preacher, K. J., Tormala, Z. L., & Petty, R. E. (2011). Mediation analysis in social psychology: Current practices and new recommendations. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 5(6), 359–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00355.x.

Ruggles, S., Flood, S., Goeken, R., Grover, J., Meyer, E., Pacas, J., & Sobek, M. (2020). IPUMS USA Version 10.0 [dataset]

Scheve, K. F., & Slaughter, M. J. (2001). Labor market competition and individual preferences over immigration policy. Review of Economics and Statistics, 83(1), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1162/003465301750160108.

Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422–445. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422.

Smith, E. R., & Mackie, D. M. (2008). Intergroup emotions. In Lewis, M., Haviland-Jones, J. M., & Barrett, L. F. (Eds.) Handbook of Emotions (3rd ed. pp. 428–439).

Sniderman, P. M., Hagendoorn, L., & Prior, M. (2004). Predisposing factors and situational triggers: Exclusionary reactions to immigrant minorities. American Political Science Review, 98(1), 35–49.

Stephens-Dougan, L. (2016). Priming racial resentment without stereotypic cues. The Journal of Politics, 78(3), 687–704. https://doi.org/10.1086/685087.

SurveyUSA. (2006). GOP Allen’s once large lead evaporates. Survey USA. Retrieve July 20, 2018 from http://www.surveyusa.com/client/PollReport_main.aspx?g=a99a9b7d-89aa-4e5f-9a0e-35d657ae1db3

Valentino, N. A. (1999). Crime news and the priming of racial attitudes during evaluations of the President. Public Opinion Quarterly, 63(3), 293–320.

Valentino, N. A., & Brader, T. (2011). The sword’s other edge: Perceptions of discrimination and racial policy opinion after Obama. Public Opinion Quarterly, 75(2), 201–226. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfr010.

Valentino, N. A., Brader, T., Groenendyk, E. W., Gregorowicz, K., & Hutchings, V. L. (2011). Election night’s alright for fighting: The role of emotions in political participation. The Journal of Politics, 73(1), 156–170. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381610000939.

Valentino, N. A., Hutchings, V. L., Banks, A. J., & Davis, A. K. (2008). Is a worried citizen a good citizen? Emotions, political information seeking, and learning via the internet. Political Psychology, 29(2), 247–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2008.00625.x.

Valentino, N. A., Hutchings, V. L., & White, I. K. (2002). Cues that matter: How political ads prime racial attitudes during campaigns. American Political Science Review, 96(1), 75–90.

Valentino, N. A., Neuner, F. G., & Vandenbroek, L. M. (2018a). The changing norms of racial political rhetoric and the end of racial priming. The Journal of Politics, 80(3), 757–771. https://doi.org/10.1086/694845.

Valentino, N. A., Newburg, J., & Neuner, F. G. (2018b). From dog whistles to bullhorns: Racial rhetoric in us presidential campaigns, 1984–2016. In: Annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Boston, MA.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The Panas scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063.

White, I. K. (2007). When race matters and when it doesn’t: Racial group differences in response to racial cues. American Political Science Review, 101(2), 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055407070177.

Zhao, X., Lynch, J. G, Jr., & Chen, Q. (2010). Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: Myths and truths about mediation analysis. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 197–206. https://doi.org/10.1086/651257.

Acknowledgements

I thank Dave Attewell, Frank Baumgartner, Lucy Britt, Ted Enamorado, Marc Hetherington, Andreas Jozwiak, Eroll Kuhn, Santiago Olivella, Tim Ryan, Candis Smith, Jim Stimson, Emily Wager, Ismail White, members of the University of North Carolina’s American Politics Research Group and State Politics Working Group, discussants and participants of the 2019 meetings of the Harvard Experimental Working Group, Midwest Political Science Association, Society for Political Methodology, and American Political Science Association, and the editor and three anonymous reviewers for their thoughtful feedback, helpful comments, and support. Replication materials are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZNBYLT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Christiani, L. When are Explicit Racial Appeals Accepted? Examining the Role of Racial Status Threat. Polit Behav 45, 103–123 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09688-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09688-9