Abstract

Background

The delayed diagnosis, altered body image, and clinical complications associated with acromegaly impair quality of life.

Purpose

To assess the efficacy of the cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) technique “Think Healthy” to increase the quality of life of patients with acromegaly.

Methods

This non-randomized clinical trial examined ten patients with acromegaly (nine women and one man; mean age, 55.5 ± 8.4 years) from a convenience sample who received CBT. The intervention included nine weekly group therapy sessions. The quality of life questionnaire the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) and the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) were administered during the pre- and post-intervention phases. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed to assess the occurrence of significant differences.

Results

According to the SF-36, the general health domain significantly improved (d′ = − 0.264; p = 0.031). The mental health domain improved considerably (d′ = − 1.123; p = 0.012). Physical functioning showed a non-significant trend toward improvement (d′ = − 0.802; p = 0.078), although four of the five patients who showed floor effects improved and remained at this level. Regarding emotional well-being, five patients showed floor effects and four improved, and the condition did not change among any of the four patients who showed ceiling effects. No significant changes were found with regard to the other domains. No significant differences in the BDI were found before or after the intervention.

Conclusion

The technique presented herein effectively improved the quality of life of patients with acromegaly with different levels of disease activity, type, and treatment time.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Acromegaly is a chronic disease characterized by the excessive production of growth hormone (GH) and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) [1,2,3]. Its characteristic coarse features and limb growth develop gradually, which complicates early diagnosis [1, 2]. Furthermore, its associated clinical complications shorten life expectancy by 10 years on average [2, 4, 5].

Quality of life is a key concept that can be assessed along a health-disease continuum [6] based on personal goals and expectations [3, 6]. Delayed diagnosis, altered body image, and clinical co-morbidities result in impaired quality of life among patients with acromegaly [2,3,4, 7, 8]. Other factors related to quality of life impairment include advanced age [9,10,11], female sex [2, 9, 10, 12], disease time [2, 12], joint pain [6, 13, 14], radiation therapy [2, 6, 7, 11, 15, 16], high body mass index (BMI), hypopituitarism [15], and active disease [2, 17]. However, a systematic review failed to reach a consensus regarding the relationship between quality of life and disease activity [15]. The quality of life impairments associated with acromegaly are similar to those observed in patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy [18].

Executive function is the largest component of cognitive processing and includes inhibitory control, working memory, problem solving, flexibility, reasoning, planning, and execution [19]. Patients with acromegaly present less activation of areas that are strongly associated with cognitive functions, such as the prefrontal and temporal cortex [19]. The literature indicates that patients with acromegaly present impaired working memory, learning, and recall process [20]. Cognitive dysfunction, mainly executive and memory dysfunction, has been observed in acromegalic patients [19]. Acromegalic patients may present impairment in their ability to execute tasks that require mental flexibility and executive functioning, in addition to presenting greater difficulty performing tasks that involve working memory [19].

Psychiatric disorders, especially depressive symptoms [4, 6, 12, 15, 21,22,23,24], anger [6, 12], anxiety [6, 23, 24], body image distortion, social isolation, and low self-esteem [4], are more commonly found in patients with acromegaly than in patients with other chronic diseases [5, 6]. Psychopathological symptoms can more strongly affect quality of life than the disease activity itself [24, 25].

Studies of medical treatments for patients with acromegaly have revealed correlations among quality of life, depression, and treatment satisfaction [7, 8]. Communication with the patient, awareness of the treatment options, and discussing problems [26] can have positive effects [7].

Emotional regulation facilitates the realistic assessment of situations experienced by the patients rather than how the patient may perceive situations due to unstable emotions [27, 28]. Because depression and anxiety states can be altered, treating these symptoms [15, 25] represents a promising way to improve patient quality of life [25].

The psychological impact of acromegaly urges the development of a cost-effective [29, 30] psychotherapeutic program [2, 4, 6, 15, 25, 31]. In this sense, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), which was developed by Aaron Beck in the 1960s [27, 28], has revealed that emotion and behavior are determined by how the individual interprets situations and not by the situations themselves [32,33,34]. Learning from one’s psychotherapeutic experience might be more beneficial than long-term pharmacotherapy with regard to preventing depressive relapses [35].

The efficacy of CBT has been assessed with regard to anxiety, anger, chemical dependence, stress related to other diseases, chronic pain, fatigue, depression, and other symptoms [36]. CBT is characterized by its high efficacy and low cost [36], which justifies the application of a program based on its principles. CBT group sessions deliver positive results and are characterized by the optimization of the therapist time in relation to individual treatment [28, 37, 38].

The six-step “Think healthy” technique didactically uses an analogy of gray and green avocado figures representing the problem and a possible alternative, respectively, to favor a less emotional and more rational decision-making process [39, 40]. This approach aims to develop healthy behaviors by restructuring unhealthy into healthy thoughts, thereby balancing the patient’s emotions and improving his or her quality of life (Fig. 1). Concurrently, the patient is asked to create lists of personal qualities and achievements.

Coping card: “Think healthy and feel the difference”. According to cognitive-behavioral therapy, the following three levels of thinking occur: (1) automatic thinking (i.e., the avocado peel), which is not related to reflection or deliberation; (2) conditional beliefs (i.e., the flesh), which is the level of cognition associated with behavior; and (3) core beliefs (seed), in which absolute or rigid thoughts are present. The figures of the gray and green avocados provide an analogy that differentiates unhealthy from healthy patterns. This technique aims to develop healthy behaviors by restructuring unhealthy thoughts into healthy thoughts, thereby balancing the patient’s emotions and improving his or her quality of life

Among patients with acromegaly, various research studies have identified the psychopathological profile of these patients to assess their quality of life and the efficacy of the available treatments to improve quality of life [15]. The present study aimed to assess the efficacy of the CBT technique “Think healthy” to improve the quality of life of patients with acromegaly. For this purpose, the 36-Item Short Form Survey (SF-36) was administered as a quality of life questionnaire. Indicators of depression were measured and compared before and after participation in the survey. To our knowledge, this study is the first to show improved quality of life using CBT in patients with acromegaly.

Method

This non-randomized clinical trial treated patients with acromegaly at the neuroendocrinology outpatient clinic of the University Hospital of Brasília.

Patients were included in this study if they were diagnosed with acromegaly, followed at this outpatient clinic, and agreed to participate in the study. Both male and female patients were included, and their ages ranged from 18 to 75 years. Suicide risk, as assessed based on the answer to item 9 of the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), was an exclusion criterion [41].

Patients were selected by convenience based on their availability to participate in this study and after describing in detail all of the intervention steps. The research project was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Health Sciences School, University of Brasília. The participants read and signed an informed consent form.

The participants received nine weekly 90-min “Think healthy” group therapy sessions from September to November 2015. These meetings were held in a room in which all participants were comfortably seated in a circle, thereby enabling them to use the materials, take notes, and complete exercises. The room was well lit, air-conditioned, and private.

Evaluation before and after the intervention

During the week before starting the group therapy sessions, the proposed work, the dates scheduled for the meetings, and the content of the sessions were presented. Data regarding age, sex, disease duration, IGF-1 levels, arterial hypertension, diabetes, arthralgia, and type of treatment (surgery, radiation therapy, oral, or injectable medication) were collected. BMI was calculated using the following formula: BMI = weight (kg)/height (m2).

The disease was considered active if the patient’s IGF-1 level was higher than the upper limit normal variation (ULNV) based on age and sex, even in the presence of cabergoline, octreotide, or pegvisomant. The disease was considered controlled if the use of these drugs kept the patient’s IGF-1 blood concentration within the normal range. The disease was considered cured when the concentration of this hormone was within the normal range without use of the above drugs. The patients were considered hypertensive if their blood pressure was equal to or greater than 140/90 mmHg or if they used antihypertensive drugs [42]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus was considered active if the patient’s glycemic index was greater than 126 mg/dL or if hypoglycemic drugs were being used [43].

Instruments

Quality of life questionnaire (SF-36)

The self-administered quality of life questionnaire SF-36 [37] was used to assess quality of life before and after the intervention. This multidimensional questionnaire consists of 36 items, which are subdivided into eight domains. Item 2 was not calculated for any domain and is used only to assess how much the individual has improved or worsened compared with a previous year. The final score ranges from 0 (zero) to 100 (one hundred), where 0 denotes the worst state, and 100 denotes the best state [37].

BDI

The self-administered BDI was used to assess depression before and after the intervention [41]. The following psychiatry patient levels were considered for this scale [41]: minimum, 0–11; mild, 12–19; moderate, 20–35; and severe, 36–63.

Intervention protocol

The “Think Healthy” technique [39, 40] is a mobile application available for download at the Apple Store and Google Play in Portuguese- and English-language versions. The brief version is shown in Fig. 1.

The “Think Healthy” exercise is completed by following the instructions, starting with a problem or unstable emotion. On the gray side, step 1 sums the emotional dysregulation and distorted thoughts that result in unhealthy behaviors.

On the colored side, step 2 sums the acceptance of the unstable emotions and healthier thoughts that result in healthy behaviors. However, maintaining unstable emotions and reliving adverse situations from the past can perpetuate the problem and reinforce unhealthy behaviors, which characterizes step 3, the return to the gray side.

Steps 4 and 5 reinforce quality of life decision-making. Step 4 values the disadvantages of the unhealthy behaviors associated with steps 1 and 3. Likewise, step 5 values the advantages of the healthy behaviors associated with step 2. Thus, the patient spends less time on the gray side and more time on the green side.

Step 6 (as part of the green side) summarizes the previous steps, with notes written on coping cards [39] that should be remembered for adverse situations. The major questions are “What would I tell a friend to think and to do, and how would he or she feel?” and “If my goal is to be healthy, then what is best to think and do now, and how will I feel?” For example, “If beauty were everything, then there would be no beautiful unhappy people, nor would there be ugly happy people”.

This technique was adapted for patients with acromegaly [39, 40], and all patients received the handouts. Specific topics were addressed in each session. To facilitate the practice of the cognitive and behavioral skills between therapy sessions, the therapy notepad and coping card deck were provided [39]. A small, laminated coping card with the avocado figures (measuring 10 × 6 cm) was handed to the patients (Fig. 1).

The following intervention group therapy sessions were conducted: session 1—the basic concepts of CBT [27]; session 2—emotional regulation; session 3—increased self-esteem and self-confidence; session 4—adaptation of the “Think Healthy” technique [39] to the practice of physical activity; session 5—anger management; session 6—fear management; session 7—acromegaly: coping with physical appearance and disease; session 8—clarification of acromegaly; session 9—summary of topics covered in the sessions.

Data analysis

The data were grouped to identify the profile of each participant and his or her progression throughout the intervention. To interpret the SF-36 dimensions, the percentage scores were calculated using normative data from the Social Dimensions of Inequality Household Survey, which was conducted in 2008 using a Brazilian sample [44]. To assess whether significant differences occurred between the pre- and post-intervention evaluations, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was performed [45]. Differences associated with p < 0.05 were considered significant. Cohen’s d was adopted to interpret the intervention effect size [46].

Results

Initially, 62 patients were invited to participate in this study. Of these, 39 patients were not interested in participating. Thirteen were willing but unable to attend the weekly sessions. Ten participants were available to participate in the therapy sessions and comprised the study subjects. The clinical characteristics of the patients are outlined in Table 1.

This table shows that nine patients were women, and patient 9 was the only man. The age of the participants ranged from 42 to 69 years. Their BMIs ranged from 21.5 to 39.2 kg/m2; one patient had a normal BMI, whereas seven were overweight, and two were obese. The diagnosis time ranged from 1 to 23 years. The time elapsed between diagnosis and the start of the study ranged from 2 to 216 months. Tumor size ranged from 8 to 34 mm. The percentage of IGF-1 concentration (i.e., the upper limit of normal variation ULNV IGF-1) ranged from 47 to 181%. Regarding disease stage, two patients were classified as cured, five patients showed controlled disease, and three showed disease activity. Regarding the treatment strategy, seven patients received transsphenoidal surgery, and four received radiation therapy after surgery. Eight patients received octreotide LAR, six of whom were also treated with cabergoline; two used pegvisomant. The most common co-morbidities were diabetes, impaired fasting glycemia, or glucose intolerance in six patients and arthralgia in six patients.

The findings before and after the CBT intervention are presented in Table 2. Significant and satisfactory improvements were observed with regard to the SF-36 in the general health domain (d′ = − 0.264; p = 0.031); seven patients improved, two showed no change, and one worsened. The mental health domain significantly and considerably improved (d′ = − 1.123; p = 0.012): nine patients improved, and only one worsened. Role limitations due to physical health (d′ = − 0.802; p = 0.078) showed a non-significant trend toward improvement: four of the five patients with floor effects improved, whereas one remained at this level. Regarding role limitations due to emotional problems, five patients showed floor effects, and four improved; all four patients who showed ceiling effects remained at this level. The other domains showed no significant changes.

Regarding the BDI depression scores, four patients had minimum scores, three had mild scores, and the remaining three had moderate scores during the pre-intervention assessment. No significant change in the results was observed before and after the intervention.

Discussion

The “Think Healthy” CBT technique improved four quality of life on the SF-36: general health, mental health, physical functioning, and emotional well-being. Regarding the number of group therapy sessions, one study showed that the results of seven sessions were similar to those of 12 sessions applied to patients with obsessive–compulsive disorder [30]. Thus, the nine sessions that the patients with acromegaly underwent induced positive results.

The “Think Healthy” technique was adapted to specific situations associated with group therapy sessions 4, 5, 6, and 7. For example, the practice of physical activity was addressed in session 4. The participants completed the exercise collaboratively. Steps 1 and 2 showed the importance of interpreting a situation rather than the situation itself [27, 38,39,40]. In general, people restructured their unstable thoughts from step 1 (i.e., “I will do it in the afternoon”/“I have other commitments”) into healthy thoughts in step 2 (i.e., “It might be helpful to invite a friend”/“It is good for my self-esteem”), thereby maintaining emotional balance and desired behaviors.

In certain situations, the construction of step 2 (i.e., the colored side) was sufficient to maintain healthy emotions and behaviors. However, unstable emotions and memories of adverse situations can perpetuate the problem, which characterizes step 3 (returning to the gray side; e.g., “I dislike it. I am too lazy. My mother is no longer here to encourage me. Doing physical activity is a waste of time…”).

Similar to patients with acromegaly, patients with social anxiety reported recurrent flashbacks related to aversive memories of social events that involved bullying and feeling humiliated. These events can trigger avoidance behaviors [47]. In patients with social anxiety, CBT reduces the number of safety and avoidance behaviors. Acceptance of both oneself and others improves [48].

Deciding what to do and how to do it as well as assessing the associated consequences is no longer a simple and easy process [49]. A healthy choice depends on balanced emotions; however, the effect of emotions on decision making is rarely studied [49]. CBT teaches patients to analyze situations from a different perspective so that their standpoint is considered a matter of choice [50, 51].

On the colored side, the risk of an unstable emotion comprising a healthy decision is minimized in steps 4 and 5 [49]. The disadvantages of a sedentary lifestyle such as “worsened pain, blood pressure, diabetes, worse bone quality; sleep deprivation; brain neglect…” were reinforced. The following advantages of physical activity were valued in step 5: “improved quality of life as a whole; improved diabetes, bone quality, and cardiac conditioning; care of the brain; maintaining the gains; and feeling well…”

As a summary of the topics addressed in the five initial steps, step 6 was constructed to “undergo medical evaluation, follow the guidelines, and practice physical activity carefully to avoid any damage.”

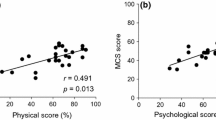

In a study of healthy participants who applied the “Think Healthy” technique [40], the abbreviated World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-bref) showed significant improvements in physical health (p = 0.05), psychological health (p = 0.04), environmental health (p = 0.01), overall health (p = 0.01), and general health (p = 0.01), but not in social relationships (p = 0.47) [40]. In comparison, the current findings were only significant in relation to general health and mental health, most likely because patients with acromegaly have a chronic and debilitating disease [4].

The high prevalence of psychopathological symptoms in patients with acromegaly that are considered successfully treated suggests that the damaging effects of excess GH and IGF-1 levels on the central nervous system are irreversible [23]. Psychopathological symptoms are observed daily, and they negatively affect quality of life more clearly than hormonal factors [25].

The significant improvement in mental health might have been facilitated by the group therapy sessions, particularly sessions 5, 6, 7, and 8. Importantly, the concepts of CBT and the “Think Health” technique were addressed in sessions 1 through 4 and were the basis of the remaining sessions.

The group therapy sessions 3, 4, 6, 7, and 8 might have contributed to the increase in role limitations due to the physical health scores in four of the five patients who initially showed floor effects.

An interesting result was also revealed with regard to role limitations due to emotional problems, in which four of the five patients who showed floor effects improved and four patients who showed ceiling effects remained at that level.

These last two domains were associated with the worst scores in relation to the normal Brazilian population [44] (Table 2). After the intervention, patients 3, 5, 6, 8, 9, and 10 showed improved physical functioning and patients 3, 4, 6, and 7 showed improved emotional well-being compared with their initial floor effect scores (Table 2).

Similar to role limitations due to physical health, pain showed a significant trend toward improvement. This result might be because of the content addressed in sessions 1, 2, 3, and 4. Improved pain and functioning is observed when educational material regarding disease is provided [13]. Approximately 90% of patients with acromegaly mention osteoarticular pain, which can worsen the physical functioning, mental health, and pain domains of quality of life compared with the normal population [13]. In the present study, six patients reported arthralgia.

Delayed diagnosis and psychosocial impairment have been reported in rural and urban patients with acromegaly because diagnosis time is significantly correlated with quality of life, depression, and body image [2]. In the present sample, most patients had a diagnosis delay of more than 2 years, which might have contributed to the decreased quality of life of this group compared with the general Brazilian population. However, this relationship apparently had no effect on the CBT results because the time of diagnosis delay varied widely, ranging from 2 (case 2) to 216 months (case 4).

The quality of life of patients with acromegaly before starting the treatment has been described as compromised [15], both when assessed using the generic SF-36 [9, 24, 52, 53] and when using a disease-specific instrument such as the Acromegaly Quality of Life Questionnaire (AcroQoL) [24, 53,54,55,56,57]. Currently, the following three treatment options are available to patients with acromegaly: surgery, radiation therapy, and drug therapy [1, 4]. These treatment modalities, alone or in combination, can affect the quality of life of patients with acromegaly [15].

One treatment (transsphenoidal surgery) among 41 Japanese patients with acromegaly induced significant improvements in four quality of life domains as assessed by the SF-36: role limitations due to physical health, general health, social functioning, and emotional well-being. These results were similar across the 26 patients who showed complete remission and the remaining 15 who showed partial remission. The CBT used in the present study significantly improved the general health of seven patients (p = 0.031) and the mental health of nine patients (p = 0.012); however, social functioning was not affected (p = 0.176). Surgery also improved the patients’ psychological functioning and appearance compared with drug treatment as assessed by the AcroQoL [55].

Many patients with acromegaly cannot control their disease with surgery alone and require treatment with pharmaceutical drugs [1, 4]. In the present study, seven patients with acromegaly received surgery, but the disease was not able to be controlled in any of these patients with this treatment alone. Several studies have suggested that adjuvant treatment to surgery [54, 55] or isolated treatment [57] with pharmaceutical drugs effectively improves the quality of life of patients with acromegaly. Patients who use long-acting somatostatin analogues as a complement to surgery have poorer scores on most of the RAND-36 scales. This questionnaire is similar to the SF-36, AcroQoL, and the fatigue inventory with regard to those who do not need to use agonists [53]. Other studies have used the AcroQoL, which complicates comparisons with our results because we only used the SF-36 to assess quality of life.

Evaluations using the AcroQoL have reported that using octreotide LAR for more than 4 years is associated with improvements in biochemical markers [54]. Isolated treatment with octreotide LAR for 24 weeks only improved the physical appearance score as assessed by the AcroQoL [58]. However, the AcroQoL and the Psoriasis and Arthritis Screening Questionnaire (PASQ) applied to patients with acromegaly initially treated with octreotide LAR, and then in combination with pegvisomant, showed that quality of life improves regardless of IGF-1 concentration [56]. The use of lanreotide autogel for more than 1 year as an isolated treatment improved the quality of life of patients with greater biochemical control as assessed by the PASQ and the AcroQoL; however, no correlation was found between the GH and IGF-1 concentrations [57].

The quality of life assessment of 58 patients with acromegaly receiving three treatment options showed that the role limitations due to physical health, vitality, and pain scores decreased compared with the patients’ emotional and psychosocial scores [24]. Radiation therapy is associated with a decrease in quality of life [55]. Four patients in the current sample were treated with surgery, radiation therapy, and drug therapy.

Eight patients in the present study used octreotide LAR, and six used cabergoline. The increase in cerebral dopaminergic tone after use of the dopamine-agonist cabergoline can trigger psychiatric problems such as compulsive shopping behaviors and sexual activity, theft and gambling, schizophrenia, psychoses, and intermittent explosive disorder (for a more detailed discussion and references, see Vilar et al.) [59]. However, none of the patients using cabergoline in the current study developed any psychiatric disorder. Furthermore, seven patients received surgery, four received radiation therapy, and only two received primary treatment with octreotide LAR. Regarding disease activity, two patients were cured, five patients showed controlled disease, and three showed active disease.

The present study showed that the worst scores were associated with role limitations due to physical health and emotional well-being during the pre-intervention assessment, regardless of the treatment received or the biochemical control. During the post-intervention assessment, two patients showed no changes in physical functioning, six improved, and two worsened. Patients 3, 4, 6, and 7 showed important improvements in role limitations due to emotional problems after the psychotherapeutic approach was applied, and participants 8, 9, and 10 showed ceiling effects even before group therapy began (Table 2).

Because of non-modifiable factors such as age, sex, disease time, and tumor size, quality of life can be improved via psychotherapeutic interventions [25, 31] that strengthen coping strategies and social support networks [23]. Thus, psychotherapeutic treatments are recommended to improve the quality of life of patients with acromegaly. To our knowledge, however, this study is the first to publish the effect that psychotherapy has on the quality of life of patients with acromegaly, despite evidence of successful results with regard to other chronic diseases [15]. CBT has shown positive results concerning the treatment of several diseases [27, 32,33,34, 39], and successful results were also obtained for the patients in the present study.

Despite the existing evidence of dysexecutive syndrome in acromegalic [19, 20], the results of this study are important. Participants were able to restructure their cognition and improve their quality of life. Some features of CBT may have facilitated improved visual and verbal memory, such as structured sessions, the use of a notepad and coping cards, collaborative exercises, and printed material.

Acromegalic patients also present partial concern during the performance of tasks involved in dysexecutive syndrome, which may impair their ability to perform everyday tasks [19]. For example, with the aim of dealing with this difficulty, participant 4 reported a “fear of doing things, even simple, when alone”. Her example was used in session 6, fear management. The following coping cards were prepared: “When I value what I do, I feel confident and overcome obstacles. At a time of fear, I must remember that I help other people and that I can do the same for myself.”

In session 6, participant 6 shared her experience and addressed her “fear of being home alone”. The disadvantages of always needing someone to stay at home (“I am a burden to other people…”) and the advantages of staying home alone were valued (“enjoying my home and putting the problems into perspective…”). Coping cards were prepared (“When I feel fear, I will use the same strategies that I used to overcome my fear of flying: I will pray…”).

In the present study, the BDI score levels of the psychiatric patients (i.e., minimum, mild, moderate, and severe) were used because of the lack of a cutoff point for patients with acromegaly [41]. In 2012, a study of 45 patients with acromegaly from the same outpatient clinic as the present research sought to assess their psychopathological profile, and 8.9% showed an indication of severe depression [60]. The prevalence of severe depression among patients with acromegaly has been reported to be 5.2% [61], 5% [7], and 3% [31]. However, no participant in the present study showed an indication of severe depression.

In the pre-intervention assessment, three participants showed an indication of moderate depression, three showed mild depression, and four showed minimal depression. The lowest depression score possible (i.e., zero) was found in only one study participant. In that case, no improvement was possible, which is considered a floor effect [62,63,64]. In addition, the decrease in BDI score was not significant.

One limitation of the current study is its small sample size; however, acromegaly is a rare disease, and the current study employed non-randomized convenience sampling using the patients who visited the clinic for treatment. Furthermore, short-term treatment might lead to relapse after completion.

In conclusion, CBT effectively improved several quality of life aspects among patients with acromegaly with various levels of disease activity, regardless of treatment time and type. Furthermore, no cases of severe depression were identified in these patients, and the therapy showed no effects on depression.

References

Vilar L, Vilar CF, Lyra R, Lyra R, Naves LA (2017) Acromegaly: clinical features at diagnosis. Pituitary 20:22–32

Siegel S, Streetz-van der Werf C, Schott JS, Nolte K, Karges W, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I (2013) Diagnostic delay is associated with psychosocial impairment in acromegaly. Pituitary 16:507–514

Dantas RAE, Passos KE, Porto LB, Zakir JCO, Reis MC, Naves LA (2013) Physical activities in daily life and physical functioning compared to disease activity control in acromegalic patients: impact in self-reported quality of life. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 57(7):550–557

Abreu A, Tovar AP, Castellanos R, Valenzuela A, Giraldo CMG, Pinedo AC, Guerrero DP, Barrera CAB, Franco HI, Ribeiro-Oliveira A, Vilar L, Jallad RS, Duarte FG, Gadelha M, Boguszewski CL, Abucham J, Naves LA, Musolino NRC, de Faria MEJ, Rossato C, Bronstein MD (2016) Challenges in the diagnosis and management of acromegaly: a focus on comorbidities. Pituitary 19(4):448–457

Fujio S, Tokimura H, Hirano H, Hanaya R, Kubo F, Yunoue S, Bohara M, Kinoshita Y, Tominaga A, Arimura H, Arita K (2013) Severe growth hormone deficiency is rare in surgically-cured acromegalics. Pituitary 16:326–332

Szcześniak D, Jawiarczyk-Przybyłowska A, Rymaszewska J (2015) The quality of life and psychological, social and cognitive functioning of patients with acromegaly. Adv Clin Exp Med 24(1):167–172

Kepicoglu H, Hatipoglu E, Bulut I, Darici E, Hizli N, Kadioglu P (2014) Impact of treatment satisfaction on quality of life of patients with acromegaly. Pituitary 17(6):557–563

Tiemensma J, Kaptein AA, Pereira AM, Smit JWA, Romijn JA, Biermasz NR (2011) Affected illness perceptions and the association with impaired quality of life in patients with long-term remission of acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96(11):3550–3558

Milian M, Honegger J, Gerlach C, Psaras T (2013) Health-related quality of life and psychiatric symptoms improve effectively within a short time in patients surgically treated for pituitary tumors—a longitudinal study of 106 patients. Acta Neurochir 155(9):1637–1645

Vandeva S, Yaneva M, Natchev E, Elenkova A, Kalinov K, Zacharieva S (2015) Disease control and treatment modalities have impact on quality of life in acromegaly evaluated by Acromegaly Quality of Life (AcroQoL) Questionnaire. Endocrine 49(3):774–782

Van Der Klaauw AA, Biermasz NR, Hoftijzer HC, Pereira AM, Romijn JA (2008) Previous radiotherapy negatively influences quality of life during 4 years of follow up in patients cured from acromegaly. Clin Endocrinol 69(1):123–128

Anagnostis P, Efstathiadou ZA, Charizopoulou M, Selalmatzidou D, Karathanasi E, Poulasouchidou M, Kita M (2014) Psychological profile and quality of life in patients with acromegaly in Greece. Is there any difference with other chronic diseases? Endocrine 47(2):564–571

Miller A, Doll H, David J, Wass J (2008) Impact of musculoskeletal disease on quality of life in long-standing acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol 158(5):587–593

Biermasz NR, Pereira AM, Smit JW, Romijn JA, Roelfsema F (2005) Morbidity after long-term remission for acromegaly: persisting joint-related complaints cause reduced quality of life. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90(5):2731–2739

Geraedts VJ, Andela CD, Stalla GK, Pereira AM, van Furth WR, Sievers C, Biermasz NR (2017) Predictors of quality of life in acromegaly: no consensus on biochemical parameters. Front Endocrinol 8:40

Kauppinen-Mäkelin R, Sane T, Sintonen H, Markkanen H, Välimäki MJ, Löyttyniemi E, Stenman UH (2006) Quality of life in treated patients with acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 91(10):3891–3896

Matta MP, Couture E, Cazals L, Vezzosi D, Bennet A, Caron P (2008) Impaired quality of life of patients with acromegaly: control of GH/IGF-I excess improves psychological subscale appearance. Eur J Endocrinol 158(3):305–310

Bonapart IE, van Domburg R, ten Have SM, de Herder WW, Erdman RA, Janssen JA, van der Lely AJ (2005) The ‘bio-assay’quality of life might be a better marker of disease activity in acromegalic patients than serum total IGF-I concentrations. Eur J Endocrinol 152(2):217–224

Shan S, Fang L, Huang J, Chan RCK, Jia G, Wan W (2017) Evidence of dysexecutive syndrome in patients with acromegaly. Pituitary 20(6):661–667

Leon-Carrion J, Martin-Rodriguez JF, Madrazo-Atutxa A, Soto-Moreno A, Venegas-Moreno E, Torres-Vela E, Benito-López P, Gálvez MA, Tinahones FJ, Leal-Cerro A (2010) Evidence of cogniitve and neurophysiological impairment in patientswith untreated naive acromegaly. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95(9):4367–4379

Mattoo SK, Bhansali AK, Gupta N, Grover S, Malhotra R (2008) Psychosocial morbidity in acromegaly: a study from India. Endocrine 34(1–3):17–22

Leistner SM, Klotsche J, Dimopoulou C, Athanasoulia AP, Roemmler-Zehrer J, Pieper L, Sievers C (2015) Reduced sleep quality and depression associate with decreased quality of life in patients with pituitary adenomas. Eur J Endocrinol 172(6):733–743

Pereira AM, Tiemensma J, Romijn JA, Biermasz NR (2012) Cognitive impairment and psychopathology in patients with pituitary diseases. Neth J Med 70(6):255–260

Kyriakakis N, Lynch J, Gilbey SG, Webb SM (2017) Impaired quality of life in patients with treated acromegaly despite log-term biochemically stable disease: results from a 5-years prospective study. Clin Endocrinol 86(6):806–815

Geraedts VJ, Dimopoulou C, Auer M, Schopohl J, Stalla GK, Sievers C (2014) Health outcomes in acromegaly: depression and anxiety are promising targets for improving reduced quality of life. Front Endocrinol 5:229

Webb SM, Badia X (2006) Validity and clinical applicability of the acromegaly quality of life questionnaire, AcroQoL: a 6-month prospective study. Eur J Endocrinol 155(2):269–277

Beck AT (1963) Thinking and depression—I—Idiosyncratic content and cognitive distortions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 9:324–333

Beck AT, Knapp P (2008) Cognitive therapy: foundations, conceptual models, applications and research. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 30(Supl II):S54–S64

Ben-Shlomo A, Sheppard MC, Stephens JM, Pulgar S, Melmed S (2011) Clinical, quality of life, and economic value of acromegaly disease control. Pituitary 14(3):284–294

Himle JA, Rassi S, Haghigthatgou H, Krone KP, Nesse RM, Abelson J (2001) Group behavioral therapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder: seven-vs. twelve-week outcomes. Depress Anxiety 13(4):161–165

Crespo I, Santos A, Valassi E, Pires P, Webb SM, Resmini E (2015) Impaired decision making and delayed memory are related with anxiety and depressive symptoms in acromegaly. Endocrine 50(3):756–763

Powell VB, Abreu N, Oliveira IR, Sudak D (2008) Cognitive-behavioral therapy for depression. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 30(2):73–80

Fava GA, Ruini C, Rafanelli C, Finos L, Conti S, Grandi S (2004) Six-years outcome of cognitive beraviour therapy prevention of recurrent depression. Am J Psychiatry 161(10):1872–1876

Padesky CA (1994) Schema change processes in cognitive therapy. Clin Psychol Psychother 1(5):267–278

de Almeida AM, Lotufo Neto F (2003) Revisão sobre o uso da terapia cognitiva-comportamental na prevenção de recaídas e recorrências depressivas. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 25(4):239–244

Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJJ, Sawyer AT, Fang A (2012) The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Cognit Ther Res 36(5):427–440

Ciconelli RM, Ferraz MB, Santos W, Meinão I, Quaresma MR (1999) Tradução para a língua portuguesa e validação do questionário genérico de avaliação de qualidade de vida SF-36 (Brasil SF-36). Rev Bras Reumatol 39(3):143–150

Kobak KA, Rock AL, Greist JH (1995) Group behavior therapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Spec Group Work 20(1):26–32

Ferreira de Lima MCGP, Kunzler LS (2017) Terapia cognitivo-comportamental nas doenças reumáticas. Capital Reum 19(3):14–19

Kunzler LS, Araujo TCCF (2013) Cognitive therapy: using a specific technique to improve quality of life and health. Estud Psicol 30(2):267–274. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0103-166X2013000200013

Cunha JA (2001) Manual da versão em Português das Escalas Beck. Casa do Psicólogo, São Paulo

IV Diretrizes Brasileiras de Hipertensão Arterial (2004) Arq Bras Cardiol 82(Supl 4):7–22

The Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus (2003) Folllow-up report on the diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 26:3160–3167

Laguardia J, Campos MR, Travassos C, Najar AL, dos Anjos LA, Vasconcelos MM (2013) Dados normativos brasileiros do questionário Short Form-36 versão 2. Rev Bras Epidemiol 16(4):889–897

Gibbons J, Chakraborti S (2011) Nonparametric statistical inference, 5 edn. Taylor & Francis, New York

Cohen J (1962) The statistical power of abnormal-social psychological research: a review. J Abnorm Soc Psychol 65(3):145–153

Wild J, Hackmann A, Clark DM (2007) When the present visits the past: updating traumatic memories in social phobia. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry 38(4):386–401

McManus F, Peerbhoy D, Clark DM (2010) Learning to change a way of being: an interpretative phenomenological perspective on cognitive therapy for social phobia. J Anxiety Disord 24(6):581–589

Bechara A (2004) The role of emotion in decision-making: evidence from neurological patients with orbital damage. Brain Cogn 55(1):30–40

Butler G, Hope T (2007) Managing your mind: the mental fitness guide, 2nd edn. Oxford University Press, New York

Luty SE, Carter JD, McKenzie JM, Rae AM, Framptom CMA, Mulder RT, Joyce PR (2007) Randomised controlled trial OS interpersonal psychotherapy and cognitive-behavioural therapy for depression. Br J Psychiatry 190(6):496–502

Fujio S, Arimura H, Hirano H, Habu M, Bohara M, Moinuddin FM, Kinoshita Y, Arita K (2017) Changes in quality of life in patients with acromegaly after surgical remission—a prospective study using SF-36 questionnaire. Endocrine J 64(1):27–38

Postma MK, Netea-Maier RT, Van den Bergh G, Homan J, Sluiter WJ, Wagenmakers MA, van den Bergh ACM, Wolffenbuttel BHR, Hermus ARM (2012) Quality of life is impaired in association with the need for prolonged postoperative therapy by somatostatin analogs in patients with acromegaly. Eur J Endocrinol 166:585–592

Mangupli R, Camperos P, Webb SM (2014) Biochemical and quality of life responses to octreotide-LAR in acromegaly. Pituitary 17(6):495–499

Yoshida K, Fukuoka H, Matsumoto R, Bando H, Suda K, Nishizawa H, Takahashi Y (2015) The quality of life in acromegalic patients with biochemical remission by surgery alone is superior to that in those with pharmaceutical therapy without radiotherapy, using the newly developed Japanese version of the AcroQoL. Pituitary 18(6):876–883

Neggers SJCMM, Van Aken MO, De Herder WW, Feelders RA, Janssen JAMJL, Badia X, van der Lely AJ (2008) Quality of life in acromegalic patients during long-term somatostatin analog treatment with and without pegvisomant. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93(10):3853–3859

Caron PJ, Bevan JS, Petersenn S, Houchard A, Sert C, Webb SM (2016) Effects of lanreotide Autogel primary therapy on symptoms and quality-of-life in acromegaly: data from the PRIMARYS study. Pituitary 19(2):149–157

Chin SO, Chung CH, Kim SW (2015) Change in quality of life in patients with acromegaly after treatment with octreotide LAR: first application of AcroQol in Korea. BMJ Open 5(6):e006898

Vilar L, Abucham J, Albuquerque JL, Araujo LA, Azevedo MF, Boguszewski CL, Casulari LA, Cunha Neto MBC, Czepielewski MA, Duarte FHG, Faria MS, Gadelha MR, Garmes HM, Glezer A, Gurgel MH, Jallad RS, Miranda PAC, Montenegro RM, Musolino NRC, Naves LA, Oliveira Júnior AR, Silva CMS, Viecceli C, Bronstein MD (2018) Controversial issues in the management of hyperprolactinemia and prolactinomas—an overview by the Neuroendocrinology Department of the Brazilian Society of Endocrinology and Metabolism. Arch Endocrinol Metab

Passos KE (2013) Avaliação do perfil psicopatológico e da qualidade de vida em pacientes acromegálicos [Dissertation]. Brasília: Universidade de Brasília

Sá AMG (2017) Fatores associados com a qualidade de vida e avaliação dos sintomas de ansiedade e depression dos pacientes acromegálicos [Thesis]. São Luis: Universidade Federal do Maranhão

Rodrigues de Paula F, Teixeira-Salmela LF, Faria CDCM, Brito PR, Cardoso F (2006) Impact of an exercise program on physical, emotional, and social aspects of quality of life of individuals with Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord 21(8):1073–1077

Faria CD, Teixeira-Salmela LF, Nascimento VB, Costa AP, Brito ND, Rodrigues-De-Paula F (2011) Comparisons between the Nottingham Health Profile and the Short Form-36 for assessing the quality of life of community-dwelling elderly. Braz J Phys Ther 15(5):399–405

Lim JB, Chou AC, Yeo W, Lo NN, Chia SL, Chin PL, Yeo SJ (2015) Comparison of patient quality of life scores and satisfaction after common orthopedic surgical interventions. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 25:1007–1012

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Luis Augusto Dias for his critical review of this manuscript. We also thank Iago Renato Peixoto, Armindo Jreige Junior, Isabella Araujo, Débora Maria de C. Saraiva, and Vitoria Espindola L. Borges, medical students at the University of Brasília. This study was conducted at the neuroendocrinology outpatient clinic of the University Hospital of Brasília.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kunzler, L.S., Naves, L.A. & Casulari, L.A. Cognitive-behavioral therapy improves the quality of life of patients with acromegaly. Pituitary 21, 323–333 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-018-0887-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11102-018-0887-1