Abstract

Kolodny and MacFarlane have made a pioneering contribution to our understanding of how the interpretation of deontic modals can be sensitive to evidence and information. But integrating the discussion of information-sensitivity into the standard Kratzerian framework for modals suggests ways of capturing the relevant data without treating deontic modals as “informational modals” in their sense. I show that though one such way of capturing the data within the standard semantics fails, an alternative does not. Nevertheless I argue that we have good reasons to adopt an information-sensitive semantics of the general type Kolodny and MacFarlane describe. Contrary to the standard semantics, relative deontic value between possibilities sometimes depends on which possibilities are live. I develop an ordering semantics for deontic modals that captures this point and addresses various complications introduced by integrating the discussion of information-sensitivity into the standard semantic framework. By attending to these complexities, we can also illuminate various roles that information and evidence play in logical arguments, discourse, and deliberation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Here is a familiar picture: Morality consists of a set of imperatives. What one ought to do is a function solely of the imperatives in force and the facts about the world. For instance, suppose you’re in a convenience store, considering whether or not to steal the chocolate bar that’s calling out to you. Given the facts and the imperatives in force—for instance, Don’t steal!—it’s obvious what you ought to do: you ought not steal the chocolate.

This type of view has a rich history. It has been articulated and defended by normative ethicists of many stripes. Here is a representative quote:

Surely what a person ought or ought not do, what is permissible or impermissible for him to do, does not turn on what he thinks is or will be the case, or even on what he with the best will in the world thinks is or will be the case, but instead on what is the case [89, pp. 178–179].Footnote 1

As Prichard puts it (though he ultimately rejects this line of thought), what one ought to do “depends [only] on the nature of the facts” [67, p. 29], that is, “facts about the world, known or unknown” (Lewis [54, p. 218]). Call deontic ‘ought’s interpreted with respect to such facts about the relevant circumstances circumstantial ‘ought’s.

As a substantive normative matter, perhaps people like Thomson are right. Even so, language and language users are not always privy to such lofty normative truths. Even if what we ought to do is what is best (in some sense) in light of the relevant external circumstances, it is well known that we can at least ask and talk about what we ought to do in view of a certain body of evidence (information, belief, knowledge).Footnote 2 (Distinctions between evidence-, information-, belief-, or knowledge-sensitive readings of ‘ought’ won’t matter for our purposes.) Deontic modals like ‘ought’ can be embedded in constructions that shift the relevant deontic standard. Suppose Alice thinks we ought to do what’s best in light of the evidence. So some deontic standards relevant to the evaluation of ‘we ought to ϕ’ in (1) are sensitive to what the evidence is.

-

(1)

a. As far as Alice is concerned, we ought to ϕ.

b. Alice thinks we ought to ϕ.

c. Given that we ought to do what’s best in light of the evidence, we ought to ϕ.

We need a semantics that can interpret evidence-sensitive readings of deontic ’ought’, that is, talk about what we ought to do in view of the evidence. We need a semantics that is neutral on substantive normative philosophical issues about whether what one ought to do can turn on features of one’s epistemic position. (I will focus my attention on weak necessity modals like ‘ought’.)

The problem is that the standard semantics for modals stemming from Angelika Kratzer [46, 47] seems to encode the normative assumptions of the familiar picture described above. It seems to assume that deontic ‘ought’s are always circumstantial ‘ought’s.Footnote 3 Simplifying somewhat, for Kratzer deontic modals quantify over those possibilities, among those consistent with certain relevant circumstances, that best approximate the deontic ideal. The standard semantics thus appears to leave open how to interpret evidence-sensitive readings of deontic modals. (We will characterize the standard semantics in greater detail in Section 3.)

Kolodny and MacFarlane [44] have made a pioneering contribution to our understanding of how the interpretation of deontic modals and conditionals can be sensitive to evidence and information. Ultimately they defend a non-standard semantics according to which the calculation of a set of deontically ideal worlds, and hence the domain of quantification for a deontic modal, is determined relative to an information state. But Kolodny and MacFarlane make no claims to integrate their discussion of information-sensitivity or their resulting analysis into the standard Kratzerian framework for modals in linguistic semantics. Doing so suggests alternative ways of capturing the data that they do not consider.

On the face of it, the fix to the standard Kratzer semantics might seem simple: We might treat evidence-sensitive ‘ought’s as quantifying over those possibilities, among those consistent with a relevant body of evidence, that best approximate the deontic ideal. However, after gathering further data regarding the behavior of deontic ‘ought’ when unembedded in root declarative clauses and embedded in conditionals (Section 2), I will show that this suggestion is insufficient (Section 4). Though this strategy fails, an alternative version of the standard semantics can indeed capture the relevant data, pace Kolodny and Macfarlane and most others in the recent literature on information-sensitivity (Section 6). A modal’s notional sensitivity to information need not be captured by treating it semantically as an “informational modal” in their sense (to be described).

Nevertheless I will argue that we have good reasons to adopt an information-sensitive semantics of the general type described in Kolodny and MacFarlane [44] (Sections 5–6). Contrary to the standard semantics, deontic rankings can themselves be information- or evidence-sensitive in the following sense: Relative deontic value between possibilities sometimes depends on which possibilities are live. Capturing this point within a (revised) Kratzerian framework raises complications, both technical and philosophical, that Kolodny and MacFarlane do not address. The main contributions of my theory, developed in Section 5, concern (a) how to capture information-sensitivity within an ordering semantics for modals and restrictor semantics for conditionals, (b) how to do so in a way that captures the variety of data and does not presuppose particular substantive normative views, and (c) how to interpret the orderings generated in the semantics. (In the Appendix I offer, within the framework of Discourse Representation Theory, one way of formalizing the more theory-neutral semantics developed in Section 5.) By attending to the complexities introduced by integrating the discussion of information-sensitivity into the standard semantic framework, we can also illuminate the various roles that information and evidence play in logical arguments, discourse, and deliberation (Section 7).

2 Data

Our child has injured himself and is badly in need of medical attention. The phones are down, and there’s no way to call an ambulance. We quickly get our son into the car and race to the local hospital. As we get closer, the traffic suddenly slows down on the highway. We near an exit for Route 1 that would, under normal conditions, get us to the hospital faster. The problem is that the city has been doing construction on Route 1 on alternating days, and we have no way of finding out (without taking the route) whether they’re doing construction on it today. If they are, we’ll get stuck, and our son will suffer serious long-term damage and may even die; but if they aren’t, we’ll be able to speed along to the hospital. If we stay put along our current route, we’ll make it to the hospital slowly but surely, but likely with some complications from the delay. As it turns out, unbeknownst to us, they aren’t doing construction on the 1; the way is clear. What should we do?Footnote 4

When we make judgments about what to do in a position of uncertainty, we often find ourselves hedging our bets in ways that we wouldn’t if we knew all the facts. (Think: insurance policy purchases.) There is a salient reading of (2)—with implicit assumptions made explicit in (3)—on which it’s true.

-

(2)

We ought to stay put.

-

(3)

In view of the evidence, we ought to stay put.

After all, we don’t know, and have no way of finding out in advance, whether there is construction on the 1, and the results will be disastrous if we switch but the 1 is blocked.

However, when we consider the case not from our limited subjective perspective but from a bird’s-eye point of view, the judgment in (4)—with implicit assumptions made explicit in (5)—can seem compelling.

-

(4)

We ought to switch to the 1.

-

(5)

In view of the relevant circumstances, we ought to switch to the 1.

After all, the way is in fact clear and switching to the 1 will get our child to the hospital most quickly.

Thus I take it that (2) and (4) each has a reading on which it is true. On the true reading of (2), the ‘ought’ is interpreted as an evidence-sensitive ‘ought’, as “ought in view of the evidence.”Footnote 5 By contrast, on the true reading of (4), the ‘ought’ is interpreted as a circumstantial ‘ought’, as “ought in view of the relevant circumstances.”Footnote 6 (Of course, since we do not have access to the facts about the traffic conditions that help make (4) true, we would not be in a position to assert (4). But our question is simply whether (4) has a reading on which it is true.)

Our first piece of data is that deontic modals can be interpreted not only with respect to a relevant body of facts about the world, known and unknown, but also with respect to a relevant body of evidence. Unembedded deontic ‘ought’ can receive both circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings. Though deontic ‘ought’ can have these different readings, I’m sympathetic with Kratzer’s view that “there is something in the meaning [of the modal]… which stays invariable” [45, p. 340].Footnote 7 So I assume that, other things being equal, it would be preferable to derive circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings of ‘ought’ from a common semantic core, or at least capture as much commonality between them as the data allows.

I should say that the distinction between circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings is perhaps not a deep conceptual distinction. One of the relevant circumstances, one might say, is that we do not know whether there is construction on the 1; in that sense, ‘In view of the relevant circumstances, we ought to stay put’ is true. True enough. But it is not counterintuitive that the sorts of facts that are targeted in phrases like ‘in view of the circumstances’ and in the relevant reading of (4) are facts about the external circumstances, or conditions in the world over which the relevant agent(s) currently has (have) no direct control. In (5), for example, ‘the relevant circumstances’ can be understood as short for “the relevant facts or circumstances concerning the traffic conditions, our current location, our child’s physical condition, our driving skills, etc.” In view of these facts, it makes sense to say that (4) is true. It is in this way that our talk about “circumstantial ‘ought’s” and what we ought to do in view of “the relevant facts or circumstances” should be understood (cf. Abusch [1]).

Second, though we can get alternative readings of unembedded deontic ‘ought’s, as brought out in the availability of both (2) and (4), there are interesting constraints on what readings are available in conditionals. The reading of ‘ought’ in ‘we ought to stay put’ is simply unavailable in a true reading of the straight ‘if p, (then) q’ hypothetical conditional:Footnote 8

-

(6)

#If the way is clear, we ought to stay put.

-

(7)

If the way is clear, we ought to switch to the 1.

In a manner to be explained, the ‘ought’ in the consequent of (7) seems to be interpreted as if the information that the way is clear is already available, this despite the fact that the antecedent of (7) is not as in (8).Footnote 9

-

(8)

a. If the way is clear and we know it, we ought to switch to the 1.

b. If we learn that the way is clear, we ought to switch to the 1.

If there is a true reading at all of a deontic conditional like (6) with (2) as its consequent clause, this reading is only available with a construction like ‘even if’ or ‘still’:

-

(9)

Even if the way is clear, we still ought to stay put.

3 The Standard Semantics

Our task is to examine whether the standard semantics can accommodate these phenomena. Let’s clarify what this “standard semantics” is. Standardly, modals are interpreted as quantifiers over possible worlds. Simplifying a bit, the domain of quantification is set by two contextually supplied parameters: a set f of accessible worlds (a “modal base”), and a preorder \(\lesssim \) (a reflexive and transitive relation) on W, where this preorder ranks worlds along some relevant dimension.Footnote 10 The modal quantifies over those worlds in the modal base that rank highest in the preorder. Different readings of modals arise from different contextual resolutions of the modal base and preorder.

Modal bases determine reflexive accessibility relations: they are sets of worlds consistent with a body of truths in the world of evaluation. For Kratzer, the two main types of modal bases are circumstantial (a set of worlds consistent with certain relevant circumstances), on the one hand, and evidence-based or epistemic (a set of worlds consistent with a certain relevant body of evidence), on the other. (I’ll use ‘epistemic’ broadly to cover modal bases describing relevant bodies of knowledge or evidence.) Hereafter I assume that our preorders are deontic and are indexed to a world of evaluation—written ‘\(\lesssim _{w}\)’ (read: “is at least as deontically good as at w”)—since, as we saw in (1), deontic modals can themselves occur in intensional contexts that shift the ordering.

A deontic selection function D can be defined to select from some domain those worlds that are not \(\lesssim _{w}\) bettered by any other world:

Definition 1

\({\forall Z{}\subseteq } W{}:{} D {(Z, \lesssim _{w})} :={}\left \{w'{}\in Z : \forall w''{}\in Z{}:{}w'' \lesssim _{w} w' {}\Rightarrow w' \lesssim _{w} w''\right \}\)

D selects the set of \(\lesssim _{w}\)-maximal (“\(\lesssim _{w}\)-best”) worlds from the modal base, those worlds in the modal base that best approximate the deontic ideal. Modals quantify over these worlds in \(D(f(w), \lesssim _{w})\). As deontic modals, on Kratzer’s view, take circumstantial modal bases, the truth-conditions for ‘Ought ϕ’ are roughly as follows. (‘⟦ ⟧’ denotes the interpretation function, a function from contexts c, indices w, and well-formed expressions to extensions.)Footnote 11

Definition 2

\(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\mathrm {Ought}\ \phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c,w} = 1\mbox { iff } \forall w' \in D(f_{\mathrm {circ}}{(w)}, \lesssim _{w}) : \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c,w^\prime } = 1\)

This says that ‘Ought ϕ’ is true iff ‘ϕ’ is true at all the best circumstantially accessible worlds.

I assume a Kratzerian restrictor analysis of conditionals on which ‘if’-clauses restrict the modal bases of various operators like modals.Footnote 12 To interpret a conditional, on this view, evaluate the proposition expressed by the consequent clause relative to (a) the preorder at the world of evaluation, and (b) the modal base at the world of evaluation restricted to worlds in which the antecedent is true:

Definition 3

\(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\mathrm {If}\ \psi ,\, \mathrm {ought}\ \phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c,w} = 1\mbox { iff } \forall w' \in D(f^{+}(w), \lesssim _{w}) : \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c,w} = 1\), where \(f^{+}(w) = f(w) \cap \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c}\). \( \left (\mathrm {Remark}: \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\alpha } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c}\,:= \left\{w{\kern-2pt}: \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\alpha } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c,w} = 1\right \}\right ) \)

This says that ‘If ψ, ought ϕ’ is true iff ‘ϕ’ is true in all the accessible ψ-worlds that are best in view of the deontic ideal at the world of evaluation.

Call this package ‘the standard Kratzer semantics’, or simply ‘the standard semantics’. There is a feature of this view that I want to highlight. On the standard semantics, the preorders with respect to which modals are interpreted are independently defined in the following sense. They are preorders on W. The only role of the modal base is to restrict our attention to different subsets of the given preorder. Specifying a modal base just knocks worlds out of the ranking; it doesn’t change how the remaining worlds are ranked. Though ‘ought’ in Definition 2 is treated as quantifying over the worlds in \(D(f(w), \lesssim _{w})\), this notation is a bit sloppy. More precisely, the standard semantics says that given a preordered set \((W, \lesssim _{w})\) and non-empty subset \(f(w)\) of W, ‘ought’ quantifies over the worlds in \(D\left (f(w), \lesssim _{w} \cap \ f(w)^{2}\right )\).

Definition 4

For a set S, its binary Cartesian product \(S^{2} = S \times S = \left \{\langle {x, y}\rangle : x \in S \wedge y \in S\right \}\).

Since \(\lesssim _{w} \cap \ f(w)^{2}\) is just a sub-preorder of \(\lesssim _{w}\), the relations between worlds as given by the preorder \(\lesssim _{w}\) on W will be maintained when we only consider the worlds in the given modal base. Informally, how worlds are ranked relative to one another is independent of which other worlds are relevant. This feature of the standard semantics will be important in what follows.

4 A Failed First Pass

This ordering semantics framework suggests two general ways of attempting to capture the difference between circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings of deontic ‘ought’: posit a shift in modal base, or posit a shift in preorder. Let’s start with the former option: there is a shift in modal base but a constant preorder in the interpretations of circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings of ‘ought’. We will return to the latter option in Section 6 after we are in a position to compare it to our alternative proposal developed in Section 5.

One might think that what changes in the interpretation of circumstantial and evidence-sensitive ‘ought’s is the set of possibilities being considered, or the modal base. This is suggested by our paraphrases of (2) and (4) in (3) and (5), respectively, reproduced below.

-

(2)

We ought to stay put.

-

(3)

In view of the evidence, we ought to stay put.

-

(4)

We ought to switch to the 1.

-

(5)

In view of the circumstances, we ought to switch to the 1.

As noted above, for Kratzer the two main types of modal bases are circumstantial and epistemic; it is the role of adverbial phrases like ‘in view of the relevant circumstances’ and ‘in view of the evidence’ to supply these respective modal bases for the interpretation of the modal. So one might think that (2) is true on its “epistemic” reading, where the modal base consists of a set of worlds consistent with the evidence (which, importantly, leaves open whether there is construction on the 1); whereas (4) and (7)

-

(7)

If the way is clear, we ought to switch to the 1.

are true on their “circumstantial” readings, where the modal base is a set of worlds consistent with the relevant circumstances (which, importantly, establish that the 1 is clear). In this way, one might think that a circumstantial modal base determines the circumstantial ‘ought’ and an epistemic modal base determines the evidence-sensitive ‘ought’ (again, where a constant deontic preorder is used in interpreting both readings). Call this hypothesis ‘modal base shift’.

Assuming a Kratzerian restrictor analysis of conditionals as given in Definition 3, the predicted truth-conditions of (7), according to modal base shift, will be as in (10).

-

(10)

\(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {(7)} \right]\kern-0.1em\right] ^{c,w} = 1\,\,\mathrm {iff}\,\,\forall w' \in D(f^{+}_{\mathrm {circ}}(w), \lesssim _{w})\): we switch to the 1 in w′, where \(f^{+}_{\mathrm {circ}}(w) = f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w) \cap \left \{w'':\ \mathrm {the\ way\ is\ clear\ in\ }w''\right \}\)

This says (7) is true iff we switch to the 1 in all the circumstantially accessible worlds in which the way is clear that are best in view of the deontic ideal at the world of evaluation.

There is something importantly right about modal base shift. However, it is insufficient as it stands. First, we do not yet have an explanation for how (2) could be true, even on its evidence-sensitive reading, given that (4) is true on its circumstantial reading. Consider two worlds w′ and w″ such that \(w' \in D(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w), \lesssim _{w})\) and \(w'' \in D(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w), \lesssim _{w})\)— where \(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\) is the set of worlds consistent with the available evidence about the road conditions, our child’s health, the location of the hospital, and so on. Though in w′ we switch to the 1 and in w″ we stay put, w′ and w″ are otherwise identical; the way is clear in both w′ and w″. Challenge: How could w′ be a \(\lesssim _{w}\)-best world in \(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w)\) but not in \(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\)? How could it be that all the \(\lesssim _{w}\)-best worlds in \(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\) aren’t all worlds where we switch to the 1, given that in some worlds in \(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\) the way is clear? We need an explanation for how and in what sense staying put could be best.

More precisely, consider the following worlds, CS, BS, CP, and BP, characterized with respect to the relevant state of the world (whether the way is Clear or Blocked) and action taken (whether we Switch or stay Put), and which are consistent with the other details of the case. (These might be treated as representatives of suitable equivalence classes of worlds.) Given our description of the case, the epistemic modal base is a subset of the circumstantial modal base. Roughly, the two are identical except for the fact that all worlds consistent with the relevant circumstances are worlds where the way is clear, whereas some worlds consistent with our evidence are worlds where the way is blocked: \(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w) = \left \{CS, CP \right \}\) and \(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w) = \left \{CS, BS, CP, BP \right \}\). (Since the way is actually clear, the evaluation world w may be either CS or CP.) Given that on their circumstantial readings (4) is true and (2) is false, we see that \(CS \in D(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w), \lesssim _{w})\) and that \(CS <_{w} CP\). The worry for modal base shift is that given that CS remains in the epistemic modal base \(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\), and given that the less long-term damage for our child the better, CS remains deontically best when BS and BP are added to the modal base.

Second, conversely, modal base shift does not account for how (4) could be true on its circumstantial reading given that (2) is true on its evidence-sensitive reading. Intuitively, since the circumstantial modal base is a subset of the epistemic modal base, if a world in the epistemic modal base is best by \(\lesssim _{w}\), it will remain best when the domain is restricted to the circumstantial modal base. More formally: Since \(\lesssim _{w}\) is just a set of ordered pairs, we can intersect it with another set of ordered pairs to yield an order preserving sub-preorder.

Definition 5

Let \(\textbf {S} = \left (S, \lesssim ^{S} \right )\) and \(\textbf {T} = \left (T, \lesssim ^{T} \right )\) be preordered sets. \(\textbf {S} \trianglelefteq \textbf {T}\) (read: ‘\(\textbf {S}\) is a sub-preorder of \(\textbf {T}\)’) if \(S \subseteq T\) and \(\lesssim ^{S} = \lesssim ^{T} \cap \ S^{2}\).

Proposition 1

Let \(\mathbf {S} = \left (S, \lesssim ^{S} \right )\) and \(\mathbf {T} = \left (T, \lesssim ^{T} \right )\) be preordered sets such that \(\mathbf {S} \trianglelefteq \mathbf {T}\). \(\forall u, v \in S : u \lesssim ^{T} v \Leftrightarrow u \lesssim ^{S} v\).

Theorem 1

Let \(\mathbf {S} = \left (S, \lesssim ^{S} \right )\) and \(\mathbf {T} = \left (T, \lesssim ^{T} \right )\) be preordered sets such that \(\mathbf {S} \trianglelefteq \mathbf {T}\). \(\forall u \in S : u \in D(T, \lesssim ^{T}) \Rightarrow u \in D(S, \lesssim ^{S})\).

Proof

Consider an element \(u^{*}\) of S. Suppose for reduction (i) that \(u^{*} \in D(T, \lesssim ^{T})\), and (ii) that \(u^{*} \notin D(S, \lesssim ^{S})\). By (i) and Definition 1, \(\forall u^\prime \in T : u^\prime \lesssim ^{T} u^{*} \Rightarrow u^{*} \lesssim ^{T} u^\prime \). But by (ii) and Definition 1 it follows that there is a world \(v \in S\) such that \(v \lesssim ^{S} u^{*} \wedge u^{*} \not \lesssim ^{S} v\). Since \(S \subseteq T, v \in T\). So \(v \lesssim ^{T} u^{*} \wedge u^{*} \not \lesssim ^{T} v\), since by Proposition 1 \(\lesssim ^{S}\) is an order preserving sub-preorder of \(\lesssim ^{T}\). Contradiction. So, \(\forall u \in S: u \in D(T, \lesssim ^{T}) \Rightarrow u \in D(S, \lesssim ^{S})\). □

The problem is that if w′ is in \(D(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w), \lesssim _{w})\), then, since \(w' \in f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w)\) and \(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w) \subset f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\), w′ is also in \(D(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w), \lesssim _{w})\). By Theorem 1, the deontically best worlds in \(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\), given that they are also consistent with the relevant circumstances, remain deontically best with respect to a contraction of the domain to \(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w)\). So modal base shift incorrectly predicts that if (2) is true, (4) is false, even when the former is given an evidence-sensitive reading and the latter is given a circumstantial reading.

Now turn to the indicative conditional in (7). The third problem for modal base shift is that in order to accommodate the felicity of (7), modal base shift would have to say that the relevant circumstances do not specify whether or not the way is clear (assuming, as is plausible, that ‘if \(p\dots \)’ presupposes that p is not settled). But the relevant circumstances do specify this; this is part of what makes (4) true. So the choice of modal base in (7) seems ad hoc. Treating the modal base as circumstantial also obscures such conditionals’ continuity with unembedded evidence-sensitive ‘oughts’. Example (2) seems as closely related to (7) as expected utility is to conditional expected utility. (We will return to this point in Section 6.)

Fourth, modifying modal base shift by treating the modal base in the conditional as epistemic still leaves problems. This is because, for Kratzer, the antecedent of a deontic conditional ‘If ψ, ought ϕ’ restricts the preorder used to evaluate ‘ought ϕ’ to preorder only the ψ-worlds. Paralleling our second argument above, we can intersect \(\lesssim _{w}\) with another set of ordered pairs—the binary Cartesian product of \(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] \)—to yield an order preserving sub-preorder used in evaluating ‘ought ϕ’. Intersecting \(\lesssim _{w}\) with \(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{2}\) yields a preorder over only ψ-worlds preordered by \(\lesssim _{w}\) that maintains the relations between them specified by \(\lesssim _{w}\).Footnote 13 So, as long as the way is clear in some world \(w' \in D(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w), \lesssim _{w})\)—or at least as long as ‘In view of our evidence, our staying put is better than our switching’ is true relative to \(\lesssim _{w}\)—if the \(\lesssim _{w}\)-best worlds out of some domain are worlds where we stay put, then the best worlds with respect to the sub-preorder \(\lesssim _{w} \cap \ \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\mathrm {the\ way\ is\ clear}} \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{2}\) will still be worlds where we stay put. modal base shift incorrectly predicts that (7) is false given that (2) is true. We still need an explanation for how (2) and (7) are both true and felicitous.

One might try to salvage modal base shift by advancing a covert higher modal analysis of deontic conditionals like (7).Footnote 14 On such an analysis, the ‘if’-clause in an overtly modalized conditional like (7) restricts the modal base of a posited higher covert modal, rather than that of the overt modal. In effect, the conditional claims that the modal sentence ‘we ought to switch to the 1’ is true in all the worlds w′ accessible from w where the way is clear. Assuming the covert modal is epistemic (as is customary), we get roughly the following truth-conditions for (7), where \(f^{+}_{\mathrm {epist}}(w) = f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w) \cap \{w''':\) the way is clear in w‴.

-

(11)

\(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {(7)} \right]\kern-0.1em\right] ^{c,w} = 1 \,\,\mathrm {iff}\,\, \forall w' \in f^{+}_{\mathrm {epist}}(w): \forall w'' \in D(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w'), \lesssim _{w'})\): we switch to the 1 in w″

A covert modal analysis might be thought to help respond to our fourth objection, that of explaining how (2) and (7) are both true, for the following reason. When evaluating the consequent clause we see what is deontically best in view of the preorder at the worlds w′ in which the way is clear. So, as long as the deontic preorder at some world w′ accessible from the world of evaluation ranks some world w″ (accessible from w′) where we switch to the 1 as best—and assuming suitable constraints on the modal base of the overt modal—(7) will be true even if (2) is true.

This response won’t itself do the trick, even putting aside the fact that it won’t help modal base shift respond to our first three objections above. First, the reply turns on the assumption that the deontic preorder at the (epistemically) accessible worlds is relevantly different from the deontic preorder at w. But we can stipulate as a feature of the case that we have no relevant normative uncertainty. The deontic preorder then won’t vary across epistemically accessible worlds. This is a problem because, if the deontic preorder is kept constant, modal base shift won’t be able to show how (7) is consistent with (2). Since modal bases determine reflexive accessibility relations, the world of evaluation w is always one of the worlds w′ in the modal base. But, as we saw in the second objection above, modal base shift cannot capture how ‘we ought to switch to the 1’ is true at w (= w′), even on its circumstantial reading; and so, it still cannot capture how (7) is true, given that (2) is true.

Here is another way of making the same point. Given that ‘we ought to stay put’ is true in the world of evaluation w, the accessible worlds that are \(\lesssim _{w}\)-best are worlds where we stay put. Now suppose that in w, the way is clear and we stay put, and that w is much like the actual world (e.g., in its laws) but is otherwise deontically perfect. So one of the \(\lesssim _{w}\)-best worlds where the way is clear is a world where we stay put. Again, since modal bases determine reflexive accessibility relations, w is one of the worlds w′ that is accessible from w. So one of the \(\lesssim _{w'}\)-best worlds accessible from the accessible worlds where the way is clear is a world where we stay put (again, assuming that all circumstantially accessible worlds are also epistemically accessible). But the conditional says that all the best worlds accessible from the accessible worlds where the way is clear are worlds where we switch to the 1. Contradiction.Footnote 15 Intuitively, (2) and (7) are both true in the specified model. But, even with a covert modal analysis, modal base shift incorrectly predicts that they are inconsistent.

There may be various ways to modify modal base shift to ward off some of these concerns. However, the arguments of this section suggest the following general lesson. It cannot simply be a shift in modal base that explains the observed variation in readings. A semantics that treats modal bases merely as restrictors of an independently defined deontic preorder will not be able to accommodate the data described in Section 2. In the next section I will outline a semantics that elucidates our data. This will obviate the motivation to add further epicycles to modal base shift. (We will return to the “shift in preorder” strategy in Section 6).

5 A Solution: Information-Reflecting Deontic Preorders

As I see it, the problem with modal base shift is not its claim that the ‘in view of’ phrases in glosses like “ought in view of our evidence” and “ought in view of the circumstances” play their usual role of specifying a modal base. The problem is that the devil’s in the preorder. I suggest that, contrary to the standard semantics, evaluations of deontic betterness among worlds in a domain can depend essentially on global properties of that domain. Deontic requirements need not simply order worlds in the modal base; they can also be sensitive to the fact that the modal base is as it is. We need the accessible worlds to be able to “see” what the other accessible worlds are like. This suggests the following glosses for (2), (4), and (7).

-

(12)

a. Given that the epistemic modal base is as it is—i.e., given that it contains both worlds where the way is clear and worlds where the way is not clear—the best of these are worlds where we stay put.

b. Given that the circumstantial modal base is as it is—i.e., given that it contains only worlds where the way is clear—the best of these are worlds where we switch to the 1.

c. If the way is clear, then, given that the updated modal base is as it is—i.e., given that it contains only worlds where the way is clear—the best of these are worlds where we switch to the 1.

There are a number of ways we might implement this informal thought. We might avail ourselves of the resources of decision theory and build probability functions and utility functions into the semantics, perhaps deriving deontic preorders from calculations of expected utility. For the sake of generality I will put this strategy aside.Footnote 16 Abstracting away from details about how deontic preorders are generated, what we need in our revised Kratzer semantics is for the generation of deontic preorders to be information-sensitive in the following sense: It needs to be sensitive to what the set being preordered is like. A world’s position in the deontic preorder cannot always be determined independently of which worlds are in the set being preordered.Footnote 17 Deontic preorders can thus reflect a world’s relative approximation of a deontic ideal, where what this ideal is can vary given different information states. In decision-theoretic terms, the preorder on worlds can be treated as reflecting, not the absolute utilities of the possible outcomes—e.g., no delay, short delay, long delay—but the expected utilities of the various acts one performs or strategies one takes in those worlds.Footnote 18

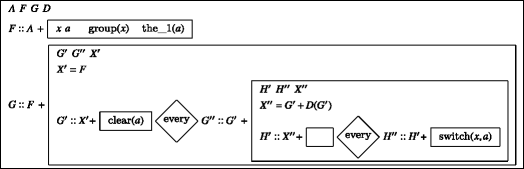

We can capture this by indexing the deontic preorder used in interpreting weak necessity modals like ‘ought’ to a world of evaluation and an information state (a set of worlds) s—written ‘\(\lesssim _{w, s}\)’. (Which information state? The information state characterizing the modal’s local context, or the original context as possibly modified by a clause or part of a clause. More on this shortly.) This suggests the following revised truth-conditions:Footnote 19

Definition 6

\(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\mathrm {Ought}\ \phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c,w}{\kern -1.5pt}={\kern -1.5pt}1\mbox { iff } \forall w' \in D(f(w), \left [ \lambda s . \lesssim _{w,s} \right ] (f(w))){}:{}\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c,w^\prime } = 1\)

As we will see, s need not represent the information state of anyone in particular. I use the term ‘information state’ in a broad sense simply to describe a set of worlds. Both epistemic and circumstantial modal bases—updated or not—represent information states in this sense. (Though more fine-grained characterizations of information states may be needed to deliver the appropriate verdicts for more complex cases—e.g., certain cases involving probabilistic information or evidence—given our purposes I bracket such complications here.)

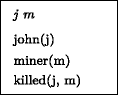

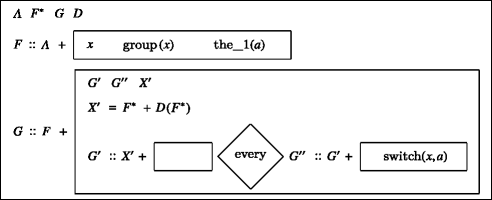

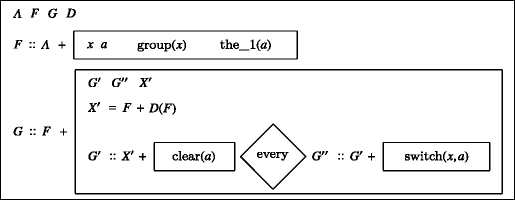

The contrast with Kratzer is important. As noted in Section 3, on the standard semantics modals are interpreted with respect to an independently defined preorder; the modal base simply restricts our attention to different subsets of it. More formally, context supplies a deontic preorder on W that is a function solely of the world of evaluation w. Fixing w fixes the preorder. The only role of the modal base \(f(w)\) is to generate a sub-preorder \(\lesssim _{w} \cap \, f(w)^{2}\), the maximal elements of which supply the modal’s domain of quantification. Consequently, if one world is ranked better than another according to the preorder, it will remain better with respect to any subset that contains both worlds as members (see Theorem 1). By contrast, on my revised picture what context supplies is a function from a modal base (and a world of evaluation) to a preorder on that modal base. In this way, the modal base does not simply restrict an independently defined preorder; it helps determine what the preorder is. As a result, two worlds can be ranked differently relative to one another when members of different modal bases. These contrasts are reflected in Fig. 1.

Definition 7

< (read: “is deontically better than”) is a strict partial order such that \(\forall w', w'': w' < w'' \Leftrightarrow w' \lesssim w'' \wedge w'' \not \lesssim w'\).

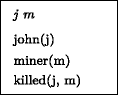

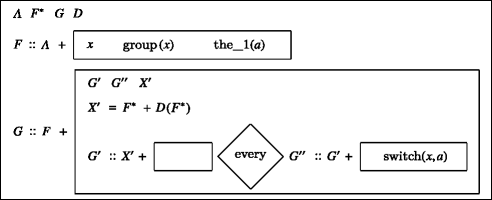

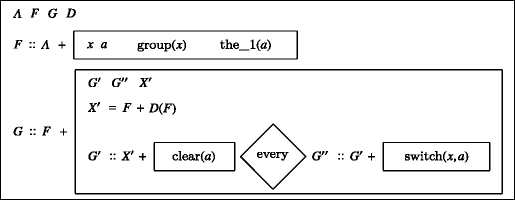

Kratzerian orders:

-

\( \begin{array}{rll} W &=& \{w_{1}, w_{2}, w_{3}, w_{4}\}. <_{w}\ = \{ \langle{w_{4}, w_{3}} \rangle, \langle{w_{4}, w_{2}}\rangle, \langle{w_{4}, w_{1}}\rangle, \langle{w_{3}, w_{2}}\rangle,\\ && \hspace*{.32in} \langle{w_{3}, w_{1}}\rangle, \langle{w_{2}, w_{1}}\rangle \} \end{array} \)

-

\( f_{1}(w) \subset W = \{w_{1}, w_{2}, w_{3}\}.\ <_{w} \cap\ f_{1}(w)^{2} = \left\{ \langle{w_{3}, w_{2}}\rangle, \langle{w_{3}, w_{1}}\rangle, \langle{w_{2}, w_{1}}\rangle \right\} \)

-

\( f_{2}(w) \subset W = \{w_{1}, w_{3}, w_{4}\}.\ <_{w} \cap\ f_{2}(w)^{2} = \left\{ \langle{w_{4}, w_{3}}\rangle, \langle{w_{4}, w_{1}}\rangle, \langle{w_{3}, w_{1}}\rangle \right\} \)

information-reflecting orders:

-

\( \begin{array}{rll} f_{3}(w) &=& {\kern-2pt} \{w_{1}, w_{2}, w_{3}\}.\ [\lambda s\ .{\kern-3pt} <_{w, s}]\left(f_{3}(w)\right)\, = \ <_{w, f_{3}(w)}{\kern-2pt}= \left\{ \langle{w_{3}, w_{1}}\rangle, \langle{w_{3}, w_{2}}\rangle, \right. \\ && \left.\langle{w_{1}, w_{2}}\rangle \right\} \end{array} \)

-

\( f_{4}(w) = \{w_{1}, w_{3}\}.\ [\lambda s\ . <_{w, s}]\left(f_{4}(w)\right) =\ <_{w, f_{4}(w)}\, = \,\left\{ \langle{w_{1}, w_{3}}\rangle \right\} \)

A word on terminology. Call a function \(\left [\lambda s\ . \lesssim _{w,s}\right ]\) from information states to preorders a preorder selector. A preorder selector is information-sensitive, in my sense, iff it is a non-constant function from information states to preorders, that is, a function that sometimes yields different preorders when given different information states as arguments. By extension I will say that a preorder is information-reflecting iff it is the value of an information-sensitive preorder selector.

Before turning to our data, it is worth mentioning that our indexing preorders to an information state does not itself imply that modals with information-sensitive and non-information-sensitive interpretations have distinct lexical entries. As noted in Sections 2–3, one perceived advantage of Kratzer’s framework is that by treating modals as context-dependent quantifiers it captures the various flavors of modality in a unified way without positing an ambiguity. The analysis here does not force us to forfeit this advantage. (Though of course one might accept that modals are ambiguous on other grounds.) All modals can be interpreted with respect to preorders that are indexed to an information state, even if some preorders are not sensitive to the value of this parameter—that is, even if some are non-information-reflecting. Information-sensitive ‘ought’ need not have a distinct lexical entry.

In the remainder of this section I will explain in a more or less theory-neutral way how information-sensitive deontic preorder selectors can help account for the data from Section 2. Revising Kratzer’s account in light of received philosophical considerations about how evidence can bear on what we ought to do generates an improved semantics that nicely predicts our data.

I noted above that deontic preorders used in interpreting ‘ought’ are to be indexed to the information state determined by the modal’s local context. In an unembedded sentence ‘Ought ϕ’, the local context is equivalent to the global context; thus, \(\lesssim \) is indexed to w and \(f(w)\).

Start with (2), our evidence-sensitive deontic ‘ought’ in a root declarative clause. Here \(s = f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\), the set of worlds consistent with the available evidence. We predict the following truth-conditions.

-

(2)

We ought to stay put.

-

(13)

\(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {(2)} \right]\kern-0.1em\right] ^{c,w} = 1\mbox { iff } \forall w' \in D(s, \lesssim _{w, s})\): we stay put in w′, where \(s = f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\)

Since the deontic preorder is indexed to the set of epistemically accessible worlds \(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\), we correctly predict that (2) is true. Since some worlds in \(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\) are worlds where the way is clear and some are worlds where the way is blocked, the \(\lesssim _{w, f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)}\)-best of these worlds will be worlds where we stay put. (Here and throughout I assume we are restricting our attention to information-sensitive preorder selectors that reflect plausible views on how deontic value depends on information.) We can thus explain our first piece of data: the true reading of (2), where ‘ought’ is interpreted as “ought in view of the evidence.” As is evident, it isn’t simply the fact that the modal base is epistemic that explains how this reading is generated. The deontic preorder also reflects what this modal base is like—specifically, that it includes some worlds where the way is clear and some worlds where it isn’t.Footnote 20

Now turn to the true reading of (4). Reflecting that the ‘ought’ is interpreted as a circumstantial ‘ought’, “ought in view of the relevant circumstances,” the relevant information state \(s^*\) will be set to \(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w)\):

-

(4)

We ought to switch to the 1.

-

(14)

\(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {(4)} \right]\kern-0.1em\right] ^{c,w} = 1\mbox { iff } \forall w' \in D(s^*, \lesssim _{w, s^*})\): we switch to the 1 in w′, where \(s^* = f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w)\)

Insofar as the information-reflecting deontic preorder is indexed to the circumstantial modal base \(s^*\)—which, importantly, includes only worlds where the way is clear—the \(\lesssim _{w, f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w)}\)-best of these worlds will be worlds in which we switch to the 1. This is the correct result.

But if the preorders used in interpreting (2) and (4) are relevantly different in these ways—insofar as they rank certain pairs of worlds differently—do circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings of ‘ought’ really count as being derived from a common semantic core (see Section 2)? Yes. On the standard Kratzer semantics, what context supplies for the interpretation of a modal isn’t, strictly speaking, a set of accessible worlds and a preorder; rather, what is supplied is a function from a world of evaluation to a set of accessible worlds and a preorder. As a result, though the relevant circumstances, for example, may vary from world to world, what is contributed for interpretation by a phrase like ‘in view of the relevant circumstances’ remains constant; it is a function from a world w to the set of worlds consistent with the relevant circumstances in w. We reflected this in the formalism by treating modal bases f as taking worlds as argument and indexing deontic preorders to worlds. The situation is precisely parallel in our revised picture. Though the deontic preorder can vary from information state to information state (and perhaps from world to world), what is contributed to the interpretation of ‘ought’ that makes it count as “deontic” remains constant; it is a function from a world and an information state to a preorder, as reflected in the formalism by double indexing the preorder to these two parameters. As captured in the truth-conditions in Definition 6, this is so regardless of whether the modal is given an evidence-sensitive or circumstantial reading. It is in this sense that our analysis derives circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings of deontic ‘ought’ in a unified way from a common semantic core.

Complicating matters a bit, let’s return to the deontic conditional in (7).

-

(7)

If the way is clear, we ought to switch to the 1.

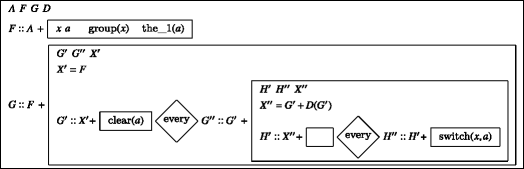

The appropriate reading for (7) is predicted from independent principles of local interpretation. Following Karttunen [42], Stalnaker [80], and Heim [36], among many others, I assume that the consequent of a conditional must be interpreted with respect to the local context set up by the antecedent—i.e., with respect to the global context (hypothetically) incremented with the antecedent.Footnote 21 Accordingly, in a deontic hypothetical conditional ‘If ψ, ought ϕ’, the preorder will be indexed to w and \(f(w) \cap \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c}\). In (7) the ‘ought’ in the consequent is interpreted with respect to the global context incremented with the proposition that the way is clear, as reflected in (15). The truth-conditions for (7) are given in (16).

-

(15)

[If the way is clear]c [we ought to switch to the 1]\(^{c_{1} = c\, \cap \, p}\)

-

(16)

\(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {(17)} \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c,w} = 1\mbox{ iff } \forall w' \in D(s^+, \lesssim_{w, s^+})\): we switch to the 1 in w′, where \(s^+ = f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w) \cap \{w'':\ \) the way is clear in w″}

The global context is, roughly, the set of worlds consistent with the evidence (see Section 4). The ‘if’-clause restricts this set to contain only worlds where the way is clear. As the modal in the consequent clause is interpreted relative to this updated context, the deontic preorder is indexed to this restricted set of worlds that encodes the information that the way is clear. Given that \(f_{\mathrm {epist}}^{+}(w)\) contains only worlds where the way is clear, the deontically best of these, relative to this updated information state, are worlds in which we switch to the 1. In this way, in conditionals like (7) we, in effect, update our epistemic state with the information expressed in the antecedent and then determine what ought to be in light of that updated information state.

6 Shifts in Preorder?

In Section 4 we noted that the standard Kratzer semantics suggests two broad ways of capturing the difference between circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings of deontic ‘ought’—namely, in terms of a difference in modal base, on the one hand, and preorder, on the other. In Section 4 I argued that positing that this difference is merely due to a shift in modal base faces serious problems. We are now in a position to assess the other type of analysis that avoids making the sorts of revisions to Kratzer’s ordering semantics developed in Section 5.

Thus far I have bracketed details regarding how the preorders used in interpreting modals are generated. In Kratzer’s theory preorders are generated by an “ordering source” g, or set of propositions (indexed to the world of evaluation): for any worlds w′ and w″, w′ is at least as good as w″ relative to the ideal set up by \(g(w)\) iff all propositions in \(g(w)\) that are true in w″ are also true in w′.Footnote 22

Definition 8

\(w' \lesssim _{g(w)} w'' := \forall p \in g(w): w'' \in p \Rightarrow w' \in p\)

In broad outline, a second strategy—call it ‘preorder shift’—aims to explain the difference between circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings of ‘ought’ in terms of a difference in ordering source. It analyzes (a) evidence-sensitive readings of ‘ought’ in terms of an ordering source that encodes the values of various outcomes conditional on (perhaps among other things) some relevant epistemic state being such-and-such way, (b) circumstantial readings of ‘ought’ in terms of an ordering source that encodes the objective values of various outcomes, and (c) hypothetical deontic conditionals in terms of the latter (objective) kind of ordering source.

The ordering source implicated in the interpretation of an evidence-sensitive ‘ought’ sentence like (2), or at least a simplified version of such an ordering source, might be something like the following.

-

(17)

\(g_{\mathrm {subj}}(w) =\)

{the way is clear and we know it \(\supset \) we switch to the 1,

the way is blocked and we know it \(\supset \) we stay put,

we don’t know whether there is construction on the 1 \(\supset \) we stay put}

With suitable constraints on the relevant modal base—e.g., assuming it’s restricted to worlds where we don’t know whether there is construction on the 1—(2), on its evidence-sensitive reading, will come out true with respect to this ordering source. The \(\lesssim _{g_{\mathrm {subj}}(w)}\)-best worlds among those where we don’t know whether the way is clear or blocked are all worlds where we stay put. These worlds make true all three propositions in the ordering source (vacuously in the case of the first two), whereas worlds in which we don’t stay put fail to make true the third proposition above. In this way, the strategy is to build information-sensitivity into the ordering source by including propositions expressed by sentences that describe relevant features of the agent’s epistemic state (and the state of the world) in the antecedents, and describe the actions available to the agent in the consequents. (For the sake of argument I bracket worries about whether an ordering source like the one in (17) will generalize to more complex cases, e.g., where the relevant epistemic states must be given a more fine-grained characterization. For I will argue that even if it can, we still have reasons to prefer an information-sensitive analysis of the sort developed in Section 5.)

By contrast, the ordering source implicated in the interpretation of a circumstantial ‘ought’ sentence like (4) might be something like this:

-

(18)

\(g_{\mathrm {obj}}(w) =\)

{the way is clear \(\supset \) we switch to the 1,

the way is blocked \(\supset \) we stay put}

With suitable constraints on the relevant modal base—e.g., assuming it’s restricted to worlds where the way is clear—(4), on its circumstantial reading, will come out true: the \(\lesssim _{g_{\mathrm {obj}}(w)}\)-best worlds where the way is clear are all worlds where we switch to the 1.

Similarly, if we assume a covert modal analysis for overtly modalized deontic hypothetical conditionals (as described at the end of Section 4), we will be able to derive the truth of (7). As suggested in the truth-conditions in (11), first we restrict ourselves to worlds w′ in which the way is clear. Assuming that the deontic ideal in these worlds is the same as that in the world of evaluation—i.e., assuming that \(g_{\mathrm {obj}}(w) = g_{\mathrm {obj}}(w')\)—the \(\lesssim _{g_{\mathrm {obj}}(w')}\)-best of the (circumstantially) accessible worlds w″ from w′ will all be worlds where we switch to the 1 (assuming that all such worlds w″ are still worlds where the way is clear). So, (7) is correctly predicted to be true.

In these ways, this implementation of the standard Kratzer semantics may be able to make the correct predictions about our example sentences (though see below). ‘Ought’s notional sensitivity to information may be captured in the semantics by encoding relevant features of the agent’s decision problem—the possible states of the world, the agent’s epistemic state, and the available actions—into propositions in the ordering source, rather than by giving ‘ought’ an information-sensitive semantics of the sort described in Section 5. This is an important point to acknowledge since much of the recent literature has assumed that the standard Kratzer semantics is necessarily inconsistent with the data.Footnote 23 The data may not force us to treat ‘ought’ as an “informational modal,” to use Kolodny and MacFarlane’s terminology [44, p. 131], or as having its domain of quantification determined relative to an information state supplied from the point of evaluation.

This leaves us with two theories, both of which are adequate to our original data. As is often the case, how we decide between them may depend largely on theoretical considerations. Though how such considerations tally up can be a subtle matter, I would like to present a preliminary case that the alternative theory developed in Section 5—call it ‘information-sensitive semantics’—is the better package deal. There are reasons for preferring a theory on which circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings of ‘ought’ result from how circumstantial and epistemic modal bases, respectively, interact with the same information-sensitive preorder selector. In short, information-sensitive semantics seems to offer a more unified analysis of all the relevant readings of deontic modals.

First, information-sensitive semantics treats phrases like ‘in view of the evidence’ and ‘in view of the circumstances’—as in (3) and (5)—as having their usual import and role: As on Kratzer’s stated view, these phrases are used to specify the two main kinds of modal bases. By contrast, preorder shift stipulates that in certain examples with deontic modals, these phrases suggest something about what ordering source is relevant (e.g., one like \(g_{\mathrm {subj}}\) or \(g_{\mathrm {obj}}\)) and do so in unpredictable ways. There is no independent motivation I know of for this stipulation.

Second, information-sensitive semantics better captures the common normative element in circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings of ‘ought’. What makes a normative modal the kind of normative modal that it is—e.g., rational, moral, prudential, etc.—is the preorder with respect to which it is interpreted. Information-sensitive semantics, unlike preorder shift, captures how it is a constant set of values or norms that are used to assess the deontic betterness-making features of acts and worlds in the interpretation of circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings of ‘ought’. (For instance, according to utilitarianism, the ordering source implicated in both readings might be something like {We maximize expected utility}, where “expectedness” is determined in light of the given modal base). As the ‘in view of the evidence’ and ‘in view of the circumstances’ phrases suggest, it is simply the relevant body of information which changes (and which then interacts with the relevant information-sensitive norm). This view also better illuminates why various normative ethicists have thought to engage in the project of attempting to analyze (in my terminology) circumstantial ‘ought’s in terms of evidence-sensitive ‘ought’s or vice versa.Footnote 24 But if the ordering sources implicated in the interpretation of both readings were logically unrelated in the manner suggested by preorder shift, this project might seem to be conceptually confused.

Third, information-sensitive semantics better captures the close semantic connection between unembedded evidence-sensitive ‘ought’ sentences like (2) and deontic conditionals like (7). As suggested in Section 4, evaluations of conditional expected utility—expected utility given a condition—play an important role in rational choice theory and decision making more generally. It would be surprising if we could not express such evaluations in natural language. Information-sensitive semantics, unlike preorder shift, captures how deontic conditionals like (7) can express such evaluations—namely, by interpreting ‘ought’ with respect to the same preorder selector that is used in interpreting unembedded evidence-sensitive ‘ought’ sentences. (Though, again, such sentences need not express judgments of expected utility, and information-sensitive preorder selectors need not be consequentialist.) Further, preorder shift seems to predict that there would be a kind of equivocation in accepting (7) and then accepting (19) upon learning that the way is clear.

-

(19)

In view of the evidence, we ought to switch to the 1.

Whatever is going on in the successive interpretations of these sentences, it does not seem that it is the ordering source that is changing. When we learn new factual information—for example, that the antecedent condition of a deontic conditional like (7) obtains—we can conclude something about what we subjectively ought to do. (As we’ll see in the following section, even if the inference from (7) and its antecedent condition to its consequent is not classically valid, it seems to be dynamically valid.)

To bring this out, consider the following variant on our original case. The case is the same as before except that now there are three ways we can get to the hospital: we can stay along our current route, we can switch to Route 1, or a bit farther down we can switch to Route 2. Route 2, like Route 1, has had construction on it lately, but when it’s clear it is the fastest route to the hospital. (When it’s blocked, it’s as slow as the 1.) We don’t know whether Route 2 is clear today, but our evidence strongly suggests that construction work is done on the 1 and the 2 on the same days. Call this case ‘route 2’. The following conditional seems true:

-

(20)

If Route 1 is clear, we ought to take Route 2.

On the condition that Route 1 is clear, switching to Route 2 is the expectably best action. Information-sensitive semantics captures this: the preorder is indexed to our current information state updated with the information that Route 1 is clear. Relative to this updated information state, our taking Route 2 is best. However, suppose that unbeknownst to us, it turns out that Route 1 is clear but Route 2 is blocked. Then, since preorder shift interprets the ‘ought’s in deontic hypothetical conditionals as having a circumstantial reading, or as taking an objective ordering source, (20) is incorrectly predicted to be false. The lesson: The ‘ought’s in deontic conditionals like (7) and (20) are not given objective or circumstantial readings. They are evidence-sensitive—or, better, evidence-sensitive on a condition.

In reply preorder shift could drop its claim that the ‘ought’ in a deontic hypothetical conditional takes an objective ordering source. Instead it could claim that the ‘ought’ is interpreted with respect to a sort of hybrid ordering source—in the case of (20), perhaps something like the following:

-

(21)

\(g_{\mathrm {subj}^*}(w) =\)

{the 1 is clear \(\supset \) we switch to the 2,

the 2 is clear \(\supset \) we switch to the 2,

the way is blocked \(\supset \) we stay put,

⋮

}

Given the sorts of assumptions discussed in the case of (7), (20) will come out true with respect to this ordering source. Preorder shift can indeed capture our new data. But, as suggested above, it does so in such a way that leaves opaque the connection between the norms used in assessing claims like (2), (4), (7), and, now, (20). More pressingly, route 2 is only the first of a long line of more complex cases in which, roughly, what is objectively best comes apart from what is expectably best, which comes apart from what is expectably best on one condition, which comes apart from what is expectably best on another condition, and so on. For each evaluation of what is expectably deontically best on a given condition C, for variable C—and for the interpretation of each associated hypothetical conditional—we will need a new ordering source. It is plausible that a theory that unifies these ordering sources and treats context as making a uniform contribution to the interpretation of all such conditionals (and their unembedded, evidence-sensitive counterpart) is to be preferred. Information-sensitive semantics does just that.

So, even if preorder shift is empirically adequate, there are good reasons for thinking that information-sensitive semantics yields the better overall theory.

7 Information-Sensitivity and Modus Ponens

So far, so good. But as the reader may have noticed, there is a perhaps surprising feature about the joint consistency of certain of our examples, reproduced below: Modus ponens is violated. (What is at issue here is the validity of modus ponens for the indicative conditional, not, e.g., the truth-functional material conditional).

-

(22)

a. We ought to stay put. (\(\Rightarrow \) It’s not the case that we ought to switch to the 1.)

b. If the way is clear, we ought to switch to the 1.

c. The way is clear.

The recent treatment of deontic conditionals in Kolodny and MacFarlane [44] has made much of this point. Though they consider a more complicated case involving constructive dilemma, this is unnecessary. The violation of modus ponens is evident even in non-hypothetical contexts, as in (22). That modus ponens fails is unsurprising given our semantics (cf. Kolodny and MacFarlane [44, pp. 137–142]). First, though it might be true that the way is clear, the epistemic modal base for the unembedded ‘ought’ in (22a) need not encode this information. Since deontic preorders can be sensitive to what the set being preordered is like, the mere truth of a proposition, together with the truth of an associated conditional ‘ought’, won’t entail the conditional’s modalized consequent. Second, since the consequent of a hypothetical conditional is interpreted with respect to its local context, the deontic preorder is sensitive to the information expressed by the antecedent in a way that affects the modal’s domain of quantification. So, the sentences in (22), even when the ‘ought’s are given the same reading without equivocation, can all be true with respect to a constant global context. (I assume that it is this notion of validity—which requires interpretation with respect to a constant global context—that is relevant for the evaluation of a logical argument for a particular conclusion.)Footnote 25

But if modus ponens fails in this way, can we still account for how, in practical deliberation, we can legitimately detach unembedded evidence-sensitive ‘ought’ claims from associated conditionals upon learning that the latter’s antecedent condition obtains? Yes: Although modus ponens is not (neo)classically valid, modus ponens inferences like the ones we are considering are dynamically valid.Footnote 26 Roughly, for a set of premises to dynamically entail a conclusion, it must be that when the premises are successively asserted (and accepted), the context set of the evolving context is included in the proposition expressed by the conclusion in that evolved context.Footnote 27 In assessments of dynamic validity, premises not only play their usual classical role of ruling out possibilities; they also change the context, and hence information state, with respect to which subsequent sentences are interpreted.

Informally, suppose we start in a context that leaves open whether the way is clear. I assert (23), which is successfully added to the common ground.

-

(23)

If the way is clear, we ought to switch to the 1.

Next, I learn that the way is clear and so assert (24).

-

(24)

The way is clear.

Since (24) is not only true but is also accepted, the context set is reduced to worlds where the way is clear. But this updated context is precisely the one relevant in the interpretation of the consequent of (23)! So, the resulting context set entails—is a subset of—the proposition expressed by (25).

-

(25)

We ought to switch to the 1.

Thus, (23) and (24) dynamically entail (25). More formally (cf. n. (21)):

Proposition 2

\(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\mathrm {If\ }\psi ,\, \mathrm {ought\ }\phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c,w} = \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c_{1}, w} = 1\, \mathit {implies} \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\mathrm {Ought\ }\phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c_{2}, w} = 1\), where \(c_{1} = c \cap \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\mathrm {If\ }\psi ,\, \mathrm {ought\ }\phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c}\) and \(c_{2} = c_{1} \cap \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c_{1}}\).

Proof

Suppose that \(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\mathrm {If\ }\psi ,\, \mathrm {ought\ }\phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c,w} = \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c_{1}, w} = 1.\) So, by Definitions 3 and 6, \(\forall w' \in D\left(c \cap \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi} \right]\kern-0.1em\right] ^{c}, \lesssim_{w,\, c\, \cap\, \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\psi} \right]\kern-0.05em\right] ^{c}}\right): \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\phi} \right]\kern-0.1em\right]^{c, w^\prime} = 1\). Suppose, plausibly, that updating with ‘If ψ, ought ϕ’ doesn’t affect the deontic preorder—i.e., that \(\lesssim _{w,\, c\, \cap \, \left[\kern-0.05em\left[ {\psi} \right]\kern-0.10em\right] ^{c}} =\ \lesssim _{w,\, c_{1}\, \cap \, \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\psi} \right]\kern-0.10em\right] ^{c}}\), indeed that \(D\left (c \cap \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c}, \lesssim _{w,\, c\, \cap \, \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.1em\right] ^{c}}\right ) \supseteq D\left (c_{1} \cap \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c}, \lesssim _{w,\, c_{1}\, \cap \, \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.1em\right] ^{c}}\right )\). Since \(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c} = \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c_{1}}, D\left (c \cap \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c}, \lesssim _{w,\, c\, \cap \, \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.1em\right] ^{c}}\right ) \supseteq D\left (c_{1} \cap \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c_{1}}, \lesssim _{w,\, c_{1}\, \cap \, \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.1em\right] ^{c_{1}}}\right )\). But \(c_{2} = c_{1} \cap \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c_{1}}\). So, it follows that \(D\left (c \cap \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c}, \lesssim _{w,\, c\, \cap \, \left[\kern-0.1em\left[ {\psi } \right]\kern-0.1em\right] ^{c}}\right ) \supseteq D\left (c_{2}, \lesssim _{w, c_{2}}\right )\). So, since \(\left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c} = \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c_{2}}, \forall w' \in D\left (c_{2}, \lesssim _{w,\, c_{2}}\right ): \left[\kern-0.15em\left[ {\phi } \right]\kern-0.15em\right] ^{c_{2},w^\prime } = 1.\) □

In conversation and deliberation we can legitimately detach claims about what we ought to do—even in the subjective, evidence-sensitive sense—from associated deontic conditionals upon learning the truth of their antecedent conditions.

8 Conclusion

Let’s take stock. On first glance it appeared that the standard Kratzer semantics for modals was incomplete; it seemed to be silent on how to interpret claims about what one ought to do in view of the evidence. While a quick fix was apparently available—namely, allowing deontic modals to take epistemic modal bases—we have seen that a more radical revision of Kratzer’s ordering semantics may be called for. On the analysis defended here, modal bases do not simply restrict deontic preorders; they help determine what the preorder is. By making the deontic preorder information-reflecting—indexed to a set of worlds—we can improve on modal base shift and preorder shift and give a unified explanation for how changes in modal base help generate circumstantial and evidence-sensitive readings of deontic ‘ought’. The intended readings of deontic ‘ought’ conditionals follow from the information-sensitivity of the preorder selector and independent principles concerning local interpretation. The project here has not been to argue that no other theory can get the data right. Rather it has been to motivate building information-sensitivity into our semantics and articulate one way of doing so that is empirically adequate and theoretically attractive.

By dropping philosophical assumptions that may have been implicit in Kratzer’s original analysis, we have opened up new ways of generating the desired predictions about various phenomena involving deontic ‘ought’. And we have done so in a way that better captures the common core of the modals than we otherwise would have. This, I take it, is an instance of a more general methodological lesson. The linguist, like any other practicing scientist, often comes to the theoretical table with various implicit philosophical views. The acceptance of such assumptions can often inadvertently restrict the space of possible analyses to be given in response to new data. By locating these assumptions, the philosopher of language can, among other things, free up the linguist and help expand the range of candidate theories.

Notes

A simple calculation of expected utility would explain the truth of (2) on its evidence-sensitive reading—using two states (clear, blocked), two acts (stay put, switch routes), and relevant assignments of probabilities to states and utilities to outcomes. However, I remain neutral here on what ultimately makes this normative conclusion correct; consequentialist, deontological, and virtue theories may all ratify it. Also, I bracket just whose evidence is relevant and remain neutral between contextualist and non-contextualist treatments, that is, neutral on whether the relevant evidential state is always supplied from the context or is sometimes supplied from a context of assessment or a parameter of the circumstance of evaluation (see, e.g., Stephenson [84], Yalcin [96], von Fintel and Gillies [23], Dowell [15], Macfarlane [56]; cf . Silk [79]).

Readers who deny that the correct deontic view is such that what we ought to do can be sensitive to features of our limited epistemic position may feel free to embed sentences under, e.g., “Given the truth of X’s beliefs about the correct deontic view.” My distinction between “circumstantial” and “evidence-sensitive” ‘ought’s closely mirrors the common distinction between “objective” and “subjective” senses of ‘ought’. I use ‘circumstantial’ instead of ‘objective’ because such interpretations simply need to be sensitive to certain contextually relevant circumstances; the objective ‘ought’ is a limiting case of this. I avoid calling the evidence-sensitive reading “subjective” for reasons that will become clear below. I use ‘circumstantial’ and ‘evidence-sensitive’ to map onto circumstantial and epistemic modal bases, respectively (see Section 3).

I use the term ‘hypothetical conditional’ in the sense of Iatridou [37].

One might say that we take (7) to be true because we reinterpret it as enthymematic for (8), implicitly assuming that we can learn whether the way is clear (see von Fintel [22]). But I take this suggestion to be something of a non-starter (see Carr [12] for further discussion). First, at least in cases with deontic ‘must’, there seems to be a contrast in acceptability between conditionals with ‘if ψ’ and ‘if we learn that ψ’ as their antecedents:

-

(i)

?If the way is clear, we must switch to the 1.

-

(ii)

If we learn that the way is clear, we must switch to the 1.

Judgments are subtle here. But informal polling suggests that, in the context as described, whereas (i) is dispreferred—we do not have an obligation to switch to the 1 conditional on how the world happens to be—(ii) is true. This suggests that the antecedent in (i) is not reinterpreted as in (ii). It would be odd if the antecedents of deontic ‘ought’ conditionals were reinterpreted in the proposed way but the antecedents of deontic ‘must’ conditionals were not. Second, the reinterpretation move is ad hoc. There is no independent mechanism I know of to motivate why this type of reinterpretation should occur in these examples. In any event, it will be instructive to examine the prospects for developing a semantics that captures how (7) as it stands, is true.

-

(i)

I make the following simplifying assumptions: I treat modal bases as mapping worlds to sets of worlds, rather than to sets of propositions (and use ‘modal base’ to refer sometimes to this function, sometimes to its value given a world of evaluation); I abstract away from details introduced by Kratzer’s ordering source; I make the Limit Assumption ([52, pp. 19–20]) and assume that our selection function is well-defined and non-empty; and I bracket differences in quantificational strength between weak and strong necessity modals. For semantics without the Limit Assumption, see Lewis [52, 54], Kratzer [46, 47], Swanson [88]. On the distinction between weak and strong necessity modals, I prefer the account in Silk [77, 78].

Thanks to Eric Swanson for this way of putting the point.

More formally: Suppose (2) is true in the world of evaluation w, and the way happens to be clear in w. Then \(\forall w' \in D(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w), \lesssim _{w}):\) we stay put in w′. Suppose the world of evaluation w is one such world \(w' \in D(f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w), \lesssim _{w})\); accordingly, we stay put in w. As noted above, \(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w') \subset f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w)\); and suppose that \(\forall w''' \in f_{\mathrm {epist}}(w): \forall u, v \in f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w'''): u \lesssim _{w'''} v \Leftrightarrow v \lesssim _{w'''} u\). (Weaker assumptions would suffice for our purposes, but these make the problem more transparent.) Then \(w \in D(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w'), \lesssim _{w'})\). So, since the way is clear in w, \(\exists w' \in f^{+}_{\mathrm {epist}}(w): \exists w'' \in D(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w'), \lesssim _{w'}):\) we stay put (and thus don’t switch to the 1) in w″—namely, where w = w′ = w″. But (7) says that \(\forall w' \in f^{+}_{\mathrm {epist}}(w): \forall w'' \in D(f_{\mathrm {circ}}(w'), \lesssim _{w'}):\) we switch to the 1 in w″. Contradiction.

This amounts to a denial of the assumption articulated in Stalnaker and Thomason [83, p. 29] and Stalnaker [82, p. 121] for the case of the similarity relation used in interpreting counterfactuals. Cf. Kolodny and MacFarlane’s treatment of deontic selection functions as “seriously information-dependent” [44, p. 133].

In the terminology from Kolodny and MacFarlane [44, p. 131], this semantics treats deontic ‘ought’ as an “informational modal.” See the Appendix for a concrete way of formalizing the largely theory-neutral analysis presented here within Discourse Representation Theory. For alternative, independently developed accounts, see Björnsson and Finlay [7], Cariani et al. [11], Charlow [13], and Lassiter [49], in addition to the seminal discussion in Kolodny and MacFarlane [44]; though I think there are good reasons for preferring an analysis along the lines presented here, for reasons of space I must reserve discussion for future work.

Examples involving claims about what some other agent ought to do in view of her evidence or claims about one ought to do in view of some other contextually salient body of information—where the agent’s evidence or the salient information differ from the evidence available in the conversational context—pose no special problems and may be treated analogously. In such cases the modal base and the information state to which the preorder is indexed is, intuitively, the one characterizing the agent’s epistemic state or the contextually salient body of information (though see footnote 5).

I am blurring the distinction between global contexts and the (epistemic) modal bases they determine. Given the sort of context-dependence we are interested in, no harm will come from this. For expository purposes I assume that the incrementing proceeds via set-intersection. The point about local interpretation might be put in terms of context change potentials; however, it is ultimately neutral between static implementations (à la Stalnaker) and dynamic implementations (à la Heim), yielding truth-conditions and context change potentials, respectively, as semantic values.

There are several ways of integrating ordering sources into our semantics from Section 5. One option would be to treat g as a function from worlds and information states to sets of propositions; g would be type \(\langle {s, \langle {st, \langle {st, t}\rangle \rangle \rangle }}\). An ordering on worlds could be generated as follows:

-

(i)

\(w' \lesssim _{g(w)(s)} w'' := \forall p \in g(w)(s): w'' \in p \Rightarrow w' \in p\)

-

(i)

For example: “on any setting for the modal base and ordering source standardly considered, the framework fails to predict the [evidence-sensitive] reading on which [(2)] is true”; “the… ordering source runs into a technical problem when it comes to the interaction with conditional antecedents” [11, pp. 14, 34; though see pp. 31–33]. “Standard quantificational semantics for deontic modals… are not able to capture these facts [about information-sensitivity]” [49, p. 136]. Cf. Kolodny and MacFarlane [44, p. 133] and Charlow [13, p. 9]. See also Dowell [16] and von Fintel [22] for discussion.

Cf. Kadmon and Landman [40], von Fintel [20, 21], Lepore and Ludwig [50, pp. 307–311]. More formally:

-

(i)