Abstract

An important aspect of identity development requires adolescents to consider and select the cultural label or labels that best fit with their conception of who they are. Yet, little is known about the longitudinal development of such labeling preferencs and their possible links with adjustment. Using longitudinal data from 180 Asian Americans (60% female; 74% U.S.-born), intra-individual and group-level changes in adolescents’ American label use were tracked. Over time, 48% chose an American label as their “best-fitting” label and 42% chose an American label at least once, but did not include an American label during at least one other time point. American label use was not associated with continuous measures of American identity, but the use of American labels was linked with lower levels of ethnic identity. American identity, whether indicated by label use or continuous scale scores, was generally linked with positive psychological and academic adjustment, with some effects of label use moderated by gender and generational status. Developmental implications of American cultural labels as markers of adolescent identity and broader adjustment are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The types of cultural identity labels that U.S. youth from immigrant families use to define themselves can have deeply meaningful implications for self and identity development, acculturation, and psychosocial adjustment (Doan and Stephan 2006; Kiang 2008). Although research focusing on adolescents’ use of cultural labels is still growing, existing work does suggest that such labels share similar theoretical functions with more traditional continuous indicators of cultural identity (e.g., regard, belonging, centrality), but also have a unique impact on developmental outcomes (Fuligni et al. 2005). Yet, given their developmental importance, labeling preferences are not well understood, especially in light of how they change over time. Particularly for youth from immigrant families, their sense of being American is understudied, despite having a role in adolescents’ lives that equals or even rivals that of ethnic identity (Deaux 2008; Kiang et al. 2013; Yip and Cross 2004).

The present study addresses this fundamental literature gap by using longitudinal data from Asian Americans to address three primary questions: (1) are there intra-individual and group-level, developmental shifts in adolescents’ American labeling preferences over time, (2) are there bidirectional links between changes in American labeling preferences and changes in American identity, as measured by more traditional, continuous scale scores (i.e., regard/centrality), and (3) are changes in American labeling preferences associated with dimensions of ethnic identity (i.e., regard/centrality; belonging, exploration), and with diverse indices of adjustment? In examining all of these questions, we also explored possible variation by generational status and gender.

Our focus on Asian Americans is notable given that they are under-studied despite comprising the fastest growing demographic group in the U.S. today (Pew Research Center 2012). Moreover, we uniquely target new gateway communities in the Southeastern U.S. where Asian Americans have increased exponentially in number, yet represent a relatively small proportion of the overall population. Recent theoretical and methodological approaches emphasize the demand for better understanding of developmental constucts among children with Asian backgrounds (Mistry et al. 2016), particularly within under-researched geographical contexts (Kiang and Supple 2016). A centered investigation into these youth’s use of cultural labels and sense of American identity could yield pivotal insight with respect to basic processes of identity formation, acculturation, and cultural adjustment.

Adolescents’ Labeling Preferences

Cultural labels appear deceptively simple, but their use can provide profound insight into adolescent identity. Diverse options exist when individuals consider and choose the identity label(s) that best define who they are, and a key developmental question is how the self-selection of these labels might change over time, particularly during the critical years of high school and emerging adulthood when identity formation is often at the forefront of adolescents’ lives (Erikson 1968). With respect to Asian Americans, which we define in the current study as individuals living in the U.S. with Asian ancestry, adolescents could use an ethnic heritage label (e.g., Chinese, Hmong) which signifies an affiliation with one’s specific heritage background, or a broader panethnic label (e.g., Asian) which could be political, strategic, and especially useful in geographical areas where specific heritage groups are small in number (Espiritu 1993; Kibria 2000; Okamoto 2006). Notably, heritage and panethnic labels can be either used alone or in conjunction with a mainstream national label (i.e., “American” for youth in the U.S.; Chinese American, Asian American).

While the adoption of an American label can signify the early steps in a sense of psychological attachment to national belonging and identity and therefore has important implications for all U.S. youth regardless of heritage background (Citrin et al. 2001), the use of an American label can take on an even deeper meaning among those with Asian backgrounds. Indeed, Asian Americans are unique in their simultaneous experience as ethnic, immigrant, and minority group members (Kiang et al. 2016). In terms of ethnicity, the selective incorporation of an American term in one’s labeling repertoire could symbolize cultural or affiliative belonging with the American culture, values, or worldview. In light of their family’s immigration history, the use of an American label could similarly indicate an affiliation with the dominant, host culture, but it could also reflect more deeply rooted feelings of bicultural acculturation (e.g., if an American label is used in conjunction with a heritage or panethnic label) or assimilation (e.g., if an American label is used alone). And, as members of a minority group, the use of an American label could represent adolescents’ engagement with the dominant status quo and perhaps even further indicate an active statement against one’s minority status. American labels could also be adopted in opposition to the experience of microaggressions which often cast Asian Americans as perpetual foriegners (Goto et al. 2002).

These identity implications that uniquely face Asian Americans can be explored by tracking patterns of how and when youth incorporate an American label into their self-concept. Developmentally, theoretical perspectives from the acculturation literature do suggest that, over time, youth from immigrant backgrounds, including Asian Americans, might explore the use of both mainstream and heritage labels as they engage in the process of identity development (Berry 2003; Phinney 2003). Over time, adolescents might adopt an integrated or bicultural identity and include an American label in their self-definitions as they mature and as their identity solidifies (Haritatos and Benet-Martínez 2002; Schwartz and Zamboanga 2008). Prior work has indeed found that more traditional indicators of American identity, as measured by regard and centrality, increase over the high school years (Kiang et al. 2013), suggesting that youth might similarly increase in their likelihood of using an American label over time.

On the other hand, it is possible that adolescents move away from using an American label over time. Drawing on conceptual models that highlight how discrimination and social inequities shape development (Garcia Coll et al. 1996; Mistry et al. 2016), Asian American adolescents could become more disengaged with their mainstream American identity over time, perhaps as a natural step in identity development as they experience social stratification (Kim 2012). For example, discrimination and microaggression research suggests that perceptions of ethnic or racial bias increase with age and can hinder feelings of belonging (Devos and Mohamed 2014). As such, perhaps Asian American youth feel more socially disenfranchised as they encounter negative racial interactions and gradually report a weaker American identification.

Clearly, more work is needed to address these competing hypotheses and clarify existing findings. It is particularly important to examine group-level patterns of American label use as well as within-person changes. For instance, in one of the few longitudinal studies focusing on labeling preferences among immigrant youth, Fuligni and colleagues (2008) found that linear trends in Latin and Asian American adolescents’ use of an American label were not evident over time, but there was substantial intra-individual variation that was influenced by other variables such as ethnic identity and language proficiency. Consistent with this line of work, we examined group-level shifts in American label use, and correlated intra-individual changes in American label use with other indicators of adolescents’ cultural identity, as measured through traditional subscale scores along both American and ethnic dimensions (e.g., regard/centrality). Other than Fuligni et al. (2008), no work of which we are aware has linked American label use with ethnic identity scores, and no existing research including Fuligni et al. has considered how American label use and American identity scores might be related.

Presumably, the use of American labels will correspond with higher continuous measures of American identity, as defined by subscales of positive regard and the centrality or importance attributed to one’s group membership (Sellers et al. 1998). More specifically, drawing on social identity frameworks (Sellers et al. 1998; Tajfel 1981), American regard can be seen to reflect individuals’ positive feelings towards and pride in being American, and American centrality can refer to the extent to which individuals feel that being American is central to their overall sense of self. While traditionally measured using separate subscales, the constructs also overlap conceptually, and some empirical work has combined these two identity subscales for parsiomony (e.g., Kiang et al. 2013). Following a similar approach, we expected to find evidence for positive links between American label use an aggregate of American regard/centrality; yet, we also went a step further to explore the opposite directionality. By examining reverse associations with American regard/centrality predicting subsequent American label use, we can gain insight into the temporal processes that might be involved.

In terms of ethnic identity, although linear acculturation models would presume that the use of an American label is inversely associated with ethnic identity (Birman and Trickett 2001; Costigan and Su 2004; Mok and Morris 2010), orthogonal perspectives would not assume such negative relations. In fact, some prior work has found that ethnic and American identity jointly ebb and flow, which suggests that these cultural identity domains develop similarly and in non-competing ways (Kiang et al. 2008; Schwartz 2007). Hence, although largely exploratory, we expected that American label use would be positively associated with continuous measures of ethnic identity, with the assumption that different identity domains go hand in hand. In addition to examining links between American label use and ethnic identity, we also investigated correlations between continuous measures of American identity and ethnic identity and similarly expected to find evidence for positive, complementary associations. The simultaneous investigation of both American labels and American identity scale scores allowed us to examine whether their effects on ethnic identity were independent of one another.

American Labels and Adjustment

Understanding nuances in adolescents’ use of an American label is important for many reasons related to identity development, but there are also notable implications in light of overall adjustment. From a social identity perspective (Tajfel 1981), the social groups to which individuals belong can serve multiple functions and promote adjustment and well-being, including operating as a source of resilience, social support, and positive affiliation. Theory and research has consistently pointed to the benefits of a strong sense of social identity, with much of the foundational work focusing on continuous subscale scores of ethnic identity (Rivas-Drake et al. 2014; Ying and Lee 1999). However, American identity is also considered a primary form of social identity for immigrant and ethnic minority youth (Oetting and Beauvais 1991; Scheibe 1983). Although some work suggests that ethnic identity can take precedence over American identity (Phinney et al. 1997), others have found that American identity, as continuously measured through indicators of regard and centrality, is positively linked with diverse developmental competencies including higher quality peer relationships, self-esteem, and academic adjustment (Kiang et al. 2013).

In extending this prior work to American labels and its implications, we expected that adolescents’ use of an American label will be linked with a diverse set of outcome variables. We considered a range of outcomes in order to gain insight into the comprehensive reach of identity labels in development. Specifically, we included two primary indicators of well-being, namely, self-esteem and depression. Given that prior work has found consistent links between ethnic identification and academic adjustment (Fuligni et al. 2005), and that the educational context itself has been argued to reflect largely Western or American values, (McBrien 2005; Pryor 2001), we also examined academic motivation as a dependent variable. As with ethnic identity, here again we examined both American labels and American centrality/regard as simultaneous predictors, and generally expected to find positive, benefical implications for adjustment.

Variation by Generational Status and Gender

In terms of generational status, prior work has supported the idea that first-generation (i.e., foreign-born) youth tend to retain their use of ethnic heritage labels and appear somewhat reluctant to use an American label to define themselves (Kiang et al. 2011). This is particularly in comparison with their U.S-born counterparts who often use a combination of panethnic, American-only, and hyphenated-American labels (Buriel and Cardoza 1993; Doan and Stephan 2006; Rumbaut 1994). Similarly, we expected that second-generation youth would be more likely to use an American label as compared to first-generation youth. However, it is possible that, over time, the use of an American label might increase among the first-generation, as their process of acculturation might drive them to identify more with their American status (Fuligni et al. 2008). Main effects of generation on label use as well as moderating effects of yearly change in labeling preferences and in yearly associations between labeling and outcomes were therefore examined.

Possible variation by gender is also important to consider. Although prior work examining gender differences in adolescents’ use of ethnic labels has been inconsistent (Fuligni et al. 2008; Portes and Rumbaut 2001), research does suggest that immigrant families differ in their socialization strategies for sons vs. daughters (Qin‐Hilliard 2003). Often, daughters are considered primary transmitters of cultural traditions and values (Bowman and Howard 1985; Dion and Dion 2001; Supple et al. 2010). Moreover, Asian American parents tend to be stricter with daughters and allow sons more social freedom (Zha et al. 2004). Consequently, with greater exposure to mainstream culture and less pressure to retain heritage cultural values and identity, boys might be more likely to use and move toward using American labels over time, as compared to girls. Considering prior work that has also pointed to main and moderating effects of gender on psychological and academic outcomes (Kiang et al. 2015; Qin 2006), we explored gender’s role as a moderator of yearly change in American labels and of links between labels and adjustment.

Current Study

The present study examined both within-person and group-level changes in adolescents’ American labeling preferences over a crucial period in identity development, namely, the four years of high school and several years post-high school into emerging adulthood. Notably, we considered competing hypotheses in terms of whether adolescents would increase or decrease in terms of their use of American labels over time.

While identifying changes in American label use is developmental important, in and of itself, we also examined within-person associations between American label use and American identity (i.e., regard/centrality), and between both American label and identity and other key developmental constructs (i.e., ethnic identity, self-esteem, depressive symptoms, academic motivation). We expected that, in any particular year, the use of an American label would be linked with higher levels of American identity. The reverse directionality was also explored. In terms of other outcomes, we generally expected that American labels and American identity would serve as positive resources in adolescents’ lives and therefore promote positive youth development across diverse indicators, including ethnic identity, self-esteem, depression, and academic motivation. Possible variation by primary demographic variables of generational status and gender was explored in light of all of these associations.

Methods

Participants

Starting with 180 9th and 10th graders, data were collected yearly for four consecutive years, with an additional follow-up approximately three to four years post-high school. Participants at the initial time of recruitment were 180 Asian American adolescents (48% were in the 9th grade cohort; 60% female) recruited from six public high schools in the Southeastern US. About 74% of the sample was U.S.-born (i.e., second-generation). Of first-generation youth, age of immigration ranged from 1–14 years (M = 5.79, SD = 4.21). An open-ended, self-report item indicated that adolescents represented divese ethnic groups including: Hmong (28%), multiethnic (mostly within Asian groups; e.g., Cambodian and Chinese) (22%), South Asian (e.g., Indian, Pakistani) (11%), Chinese (8%), panethnic (i.e., Asian) (8%), and small clusters such as Montagnard, Laotian, Vietnamese, Filipino/a, Japanese, Korean, and Thai (23%).

Procedure

A stratified cluster design identified public high schools in central North Carolina with high Asian growth and a student body with relatively large proportions of Asian students for the region (3–10%). The schools differed in overall ethnic diversity, size, achievement, and socioeconomic status. In small group settings, students identified as Asian through school matriculation forms were invited to participate in a study on the social and cultural issues that affect their daily lives. Approximately 60% of those invited to participate returned consent/assent forms. During a follow-up school visit, these participants were administered a packet of questionnaires during school time which took about 30–45 min to complete. All measures were completed in English.

Participants completed follow-up surveys each year for three additional years. All questionnaires remained consistent in content and length throughout waves. For Waves 2 and 3, researchers returned to schools to distribute questionnaires during class time. Participants were sent questionnaires in the mail if they were no longer in school or if absent the day the surveys were administered. For Wave 4, we collected data entirely through postal mail given that the older cohort was no longer in high school. Adolescents received $25 for Wave 1 of the study (which involved an additional daily diary component), $15 for W2 and W3 each, and $20 for W4. The retention rate in W2 was approximately 91%. About 87% of the original sample was retained in W3, and 77% in W4.

Approximately three to four years post-high school, participants were contacted via e-mail and postal mail and invited to participate in an additional follow-up. We were able to reach and hear back from 43% of the original sample and, of these, all agreed to participate in the post-high school follow-up. Although these participants were given the option to complete paper surveys to be sent via postal mail, all opted to complete the surveys online. Compared to participants who were retained at this final wave, those who were missing from the follow-up in emerging adulthood were more likely to be male (71% vs. female: 50%; Χ 2 = 7.37, p < .01) and to not have been born in the United States (72% vs. U.S.-born: 54%; Χ 2 = 4.75, p < .05). Because of these differences, follow-up sensitivity analyses were conducted without the final follow-up wave of data. These results are reported throughout.

Measures

All of the following measures were collected during each wave of the study.

Labeling Preferences

Adolescents were shown an extensive list of cultural labels, used successfully in prior research with youth from immigrant backgrounds (Fuligni et al. 2008), and were asked to check which ethnic label(s) describe them. They were instructed to choose as many labels as they want, and also had an opportunity to write in any label(s) not on the list. In an open-ended format, adolescents were then asked to indicate what label they believe best describes them. These open-ended responses were then coded to reflect adolescents’ primary labeling preferences. Categories included ethnic heritage (e.g., Laotian, Chinese), panethnic (e.g., Asian), heritage-American (e.g., combination of any heritage labels plus American, either listed with a hyphen or not), panethnic-American (e.g., combination of Asian and American, hyphenated or not), and American only.

American Identity

A shortened Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity (MIBI) used in prior work (Yip et al. 2006) measured American identity. The 4-item regard subscale measures positive feelings toward one’s group (e.g., I feel good about being American). The 4-item centrality subscale assesses whether one’s social identity is central to one’s self-concept (e.g., In general, being American is an important part of my self-image). All items are scored from 0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree with higher scores reflecting higher regard and centrality (American regard αs = .87−.91; American centrality αs = .89−.91). As expected, acoss study waves, continuous measures of American regard and centrality were strongly correlated (rs = .82−.90, ps < .001) and therefore combined in all analyses.

Ethnic Identity

Items from the regard and centrality subscales of the MIBI were also adapted and used to measure ethnic identity. A sample item reflecting ethnic regard reads, “I feel good about being a member of my ethnic group.” A sample ethnic centrality item reads, “In general, being a member of my ethnic group is an important part of my self-image. Again, items are scored from 0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree with higher scores reflecting higher regard and centrality (ethnic regard αs = .88−.91; ethnic centrality αs = .87−.90). As expected, ethnic regard and centrality subscales were significantly correlated (rs = .75−.86, ps < .001). We thus created composites for ethnic identity by averaging the subscales, and these composite variables were included in the models below.

Two additional subscales of ethnic identity from the Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM; Phinney 1992) measured ethnic affirmation/belonging and exploration. Affirmation/belonging reflects feeling a sense of pride and affiliation with one’s ethnic group (e.g., “I have a strong sense of belonging to my own ethnic group”) and consists of five items. Exploration, consisting of seven items, reflects devoting active time and thought to understanding the meaning of and learning more about one’s ethnic group membership (e.g. “I have spent time trying to find out more about my own ethnic group, such as its history, traditions, and customs”). Items were rated on a 5-point, Likert-type scale (0 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree). Across the study waves, alphas ranged from .75 to 83 for affirmation/belonging, and .89 to .92 for exploration.

Self-Esteem

The widely-used 10-item Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Rosenberg 1986) measured self-esteem. Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree, with higher values indicating higher self-esteem. A sample item reads, “I feel that I have a number of good qualities.” The alphas across study waves ranged from .84−.87.

Depressive Symptoms

The widely-used 10-item depression scale (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale-10; Andresen et al. 1994) assessed adolescents’ depressive symptoms experienced within the previous week. All items are scored from 0 = rarely or none of the time to 3 = all of the time. Higher scores indicate higher levels of depressive symptoms. Internal consistencies across study waves ranged from .75 to .80.

Academic Motivation

Drawing on prior work (Eccles 1983), two items successfully used in Asian American samples (Fuligni et al. 2005) measured intrinsic motivation. On a scale of 1 = very boring to 5 very interesting, youth were asked, “In general, I find working on school work…” A second item asked, “How much do you like working on school work?” using a 1 = a little to 5 = a lot scale. Across study waves, these items were significantly correlated with each other, r range from .69 to .72.

Results

Patterns of American Label Use

The first goal of the study was to explore participants’ use of an American label in terms of both intra-individual and linear change. As shown descriptively in Table 1, few participants chose American as a stand-alone label at any of the time points, although U.S.-born youth often chose it in combination with a heritage or pan-ethnic label.

Intra-individual change in the use of an American label was notable. While the American label was not used frequently at any single time point, nearly half of the participants (48.1%) chose an American label, either alone or in combination, at least once over the course of the study, with this rate being higher for U.S.-born (57.1%) than for foreign-born youth (21.3%), Χ 2 = 17.91, p < .001. Among the participants with at least two waves of data (n = 157), 42.0% had at least one wave in which they reported an American label, whether on its own or in combination with a heritage or panethnic label, and another in which American was not included at all in their label. U.S.-born youth were more likely to exhibit this pattern of using both types of labels (i.e., including American and not including American) across the waves (47.9%) than were foreign-born youth (20.0%), Χ 2 = 8.72, p < .01.

Hierarchical Linear Modeling (HLM; Bryk and Raudenbush 1992) tested the following model to explore the extent to which there were linear changes in American label use:

As shown in Eq. 1, adolescents’ use of an American label (whether alone or with a heritage or panethnic label) (i) for a particular year (j) was modeled as a function of the individual’s average rate of using an American label (b0j) and year (b1j). Equations 2 and 3 show how the average rates of American label use and the effect of year were modeled as a function of the adolescent’s gender and generational status. Year was coded as 9th grade = 0, 10th grade = 1, 11th grade = 2, 12th grade = 3, one-year post-high school = 4, follow-up in emerging adulthood = 5 and was uncentered. The level 2 variables were grand mean centered. Gender was coded as females = 0 and males = 1, and U.S.-born was coded as 0 = foreign-born (i.e., first-generation) and 1 = U.S.-born (i.e., second-generation). Given that whether or not an American label was chosen was a dichotomous outcome, these analyses were run using a Bernoulli distribution. Time was only marginally related to American label use (b = .09, p = .06). This did not vary by nativity, but was marginally stronger for boys than for girls (b = .19, p = .06). This pattern varied somewhat when we excluded the follow-up time point. There was no main effect of time, although the effect of time was moderated by generation (b = .34, p < .05) such that U.S.-born adolescents were more likely to choose an American label over time

Associations between American Label Use and Strength of American Identity

The next goal was to examine intra-individual associations between American label use (either alone or in combination with a heritage or panethnic label) and American identity, as measured through the continuously-scored aggregate of regard and centrality. HLM analyses were conducted to examine year-to-year associations. To gain some insight into directionality, separate models were tested with American label use as the outcome variable and American identity as a predictor, and with American identity as the outcome and American label use as a predictor. Whether a participant was U.S.-born and gender were both included as level 2 control variables and year of the study was included as a control variable at level 1. For the model with American identity as the outcome variable, the estimated statistical model was as follows:

As shown in Eq. 4, American identity (i) for a particular year (j) was modeled as a function of adolescents’ average level of identity (b0j), whether or not an American label was used (whether on its own or in combination with a heritage or panethnic label; b1j), and year of the study (b2j). Equations 5–7 show how the average levels of identity and the effects of American label use and time were modeled as a function of gender and generation. The level two variables were coded and centered as before. Choosing an American label in any given year was not linked with American identity (b = .13, p = .17) and there was no variation by nativity or gender.

The model was also reversed, with American label as the outcome variable and American identity as the predictor, controlling for time. American identity was uncentered in this analysis. Given that whether or not an American label was chosen was a dichotomous outcome, this analysis was run using a Bernoulli distribution. Again, there was no significant association between American identity and use of the American label (b = .14, p = .16), and no variation by generational status or gender was found.

As before, these tests were re-run with the post-high school follow-up wave of data excluded. Results were substantively the same, with no significant associations between American label use and strength of American identity, regardless of the direction of the analysis.

Year-to-Year Associations between American Label Use and Adjustment

Our final goal was to examine the independent influences of American label use and American identity on adjustment. A range of outcomes was explored, including strength of ethnic identity, psychological well-being, and academic motivation. For each outcome, the following model was tested:

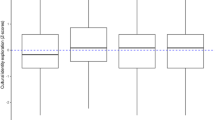

All level 2 variables were coded and centered as before. As shown in Table 2, the patterns of results varied somewhat across adjustment indicators. In terms of ethnic identity, on a year-to-year basis, American label use was associated with lower ethnic identity, across all three subscales. On the other hand, strength of American identity was positively linked with ethnic identity. With the exception of a marginal effect of nativity on the link between American label use and ethnic belonging, none of these associations varied by gender or generation.

In terms of psychological adjustment, the use of an American label was not associated with self-esteem or depression for the sample as a whole, although it was associated with lower levels of self-esteem for girls. However, strength of American identity, as assessed through continuous measures, was positively associated with self-esteem and negatively associated with depression. Finally, strength of American identity was also significantly and positively linked to academic motivation. The association between American label use and motivation varied according to nativity, with U.S.-born youth reporting higher motivation in waves in which they used an American label and foreign-born youth reporting lower motivation in those years.

Results without the final follow-up wave of data varied from those presented here in only one case. Without the follow-up wave, the association between American identity and depression was not significant (b = −.02, p = .60).

Discussion

Coming to terms with one’s identity is a developmental process (Erikson 1968) and, with respect to the many social identification and labeling options that exist, there is infinite variability and great complexity in how adolescents’ identity or self-concept might develop (Deaux 2008). The goal of the present study was to center on one salient aspect of identity for Asian American youth, namely, their sense of being American as measured by the incorporation of the term as a part of their preferred cultural labels. Multi-wave reports allowed us to examine both intra-individual and linear patterns of American label use over time, as well as how such labeling preferences are associated with year-to-year changes in other developmentally salient constructs (i.e., American and ethnic identity, psychological well-being, academic adjustment).

Similar to prior longitudinal work focusing on changes in adolescents’ ethnic identification over time (Fuligni et al. 2008; Kiang et al. 2010), there was limited evidence of linear change in the use of an American label. More specifically, although adolescents did increase in their incorporation of an American label over time, this effect was only marginally significant. Moreover, this group-level effect was marginally stronger for boys than for girls, and when the dataset was restricted to exclude the follow-up data point, particularly for U.S.-born adolescents. Perhaps adolescents become more aware of their diverse social identities as they gain new experiences through work or education (Phinney 2003). Emeriging adults could also leverage their greater independence and autonomy to redefine or learn more about their identities in ways that incorporate their affiliation with being American (Ethier and Deaux 1994). These experiences could be especially salient for boys, who are typically allowed more freedom and are held less accountable as heritage cultural transmitters than are girls (Supple et al. 2010; Zha et al. 2004). That said, it is important to note that linear change could mask individual-level trends, and that group increases (or decreases) in American label use could reflect temporary shifts that continue to fluctuate as individuals engage in ongoing identity development processes.

In general, it is also important to highlight that approximately 48% of our sample chose an American label at some point over the course of the study period. Also, these preferences for American labels were more frequent among U.S.-born adolescents than among their foreign-born counterparts, and such preferences were most often coupled with either a heritage or panethnic label. The fact that an American label was seldom selected alone suggests that ethnic identity remained salient to the Asian Americans in our sample. Preferences for the use of a hyphenated-American label suggests that these youth likely embraced a bicultural identity orientation in selecting both American and ethnic-related labels in their ethnicity-based self-definitions (Berry 2003; Phinney 2003). Furthermore, given Asian Americans’ simultaneous status as members of ethnic, immigrant, and minority groups (Kiang et al. 2016), their use of American labels could also reflect their recognition of their family’s cultural and immigration history coupled with an active acknowledgement of their rights and status as part of the mainstream society as well. Taken together, there appears to be great variability in terms of whether Asian American adolescents will intentionally incorporate the idea of being American into their overall sense of cultural identification and, as a result, perhaps such variation might be best modeled as a function of individual differences rather than normative change.

Indeed, the limited group predictability in the use of an American label does not preclude the idea that substantial intra-individual variation can be found. In fact, 42% of the sample included an American label at one wave of the study, but not at another wave. Hence, it appears that, over high school and emerging adulthood when identity development is theoretically at the forefront of adolescents’ lives (Erikson 1968; Phinney et al. 1997), adolescents “try on” different labeling options and seem to experiment with or explore the diverse categories that exist. Such identity exploration processes could be particularly meaningful for Asian American youth who must grapple with multiple levels or dimensions of cultural identity, including their American and heritage backgrounds.

Given such intra-individual variation, an additional goal of the present study was to uncover correlates of within-person change. In terms of links with other domains of identity, we found that choosing an American label in any given year was not actually associated with continuous indicators of American regard/centrality. Similarly, no evidence was found for the reverse associations, with American identity predicting the use of an American label. Interestingly, these results suggest that cultural labels, while serving as a meaningful index of identity (Doan and Stephan 2006; Kiang 2008), are also independent from more traditional measures of identification. Social identity theory (Tajfel 1981) argues that social identification involves multiple dimensions including both knowledge of one’s group membership and the emotional significance of such membership. Perhaps labeling measures tap into the knowledge aspect of social identity, while the continuous measures of American regard/centrality that we used in the current study assess more of the emotional or psychological aspect of one’s group identity, and both of these broad identity dimensions reflect relatively unique developmental processes. That is, the manner in which adolescents engage with and select the cultural labels that best fit with their current conception of who they are could constitute a wholly distinct process from determining how positively they feel about their group membership or how important that group membership actually is in one’s life. It appears equally plausible for some adolescents to use an American label and experience accompanying levels of positive regard/centrality, as it is for other adolescents to use an American label and not report the same levels of identity. Similarly, adolescents could experience positive American regard/centrality but choose not to use an American identifier in their self-definition.

It is also possible that different variations of American label use (e.g., heritage-American vs. panethnic American vs. American only) have different associations with continuous measures of American identity, but that our relatively small sample which necessitated our merging of all of these variations into a single category masked any predictable effects. Yet another possibility is that, during adolescence and emerging adulthood, individual variation in identity constructs are so in flux that no predictable associations among them can be deciphered. More research incorporating longitudinal data, a larger sample, and perhaps a wider range of development could help to replicate and further extend our results.

The lack of association between American label use and continuous measures of American identity supports the need to examine their independent associations with adjustment. In terms of ethnic identity, American label use was generally associated with lower ethnic identity reported across all three subscales (ethnic regard/centrality, belonging, exploration). Although more research is needed to clarify these results, it appears that the use of an American label could hinder ethnic identity, proving support for a linear model of acculturation (Birman and Trickett 2001; Costigan and Su 2004; Mok and Morris 2010. However, support for orthogonal approaches are also supported (Kiang et al. 2008; Schwartz 2007) in the sense that continuous measures of American and ethnic regard/centrality were positively correlated.

Although the patterns found could be due to a measurement artifact, it does appear that aggregates of American and ethnic pride and centrality are generally concordant, yet the selection of an American term as a best-fitting cultural label can oppose ethnic identity. Perhaps the use of American labels reflects a particularly strong identity statement that negates other forms of identity and hinders exploration of other identity domains. As stated earlier, these results could also be due to limitations in our conceptual grouping of all American terms, whether they were used alone or in conjunction with other labels. Still, these findings point to the need to further clarify the potentially unique effects of American label use and continuous indicators of American identity in shaping youth development.

In terms of more basic associations with adjustment, American label use was not directly associated with any adjustment variables for the sample as a whole. However, corresponding to prior work pointing to important implications of traditional scale measures of American identity (Gartner et al. 2014; Oetting et al. Beauvais 1991; Scheibe 1983), our combined construct of American regard and centrality was positively associated with self-esteem and academic motivation, and negative associated with depressive symptoms. The more consistent and powerful impact of American identity, and not American labels, is also in line with prior work pointing to the significant effects of ethnic identity, but not ethnic labels, in predicting academic adjustment among Latin and Asian American youth (Fuligni et al. 2005).

It is also important to note that some links between American label use and outcomes were moderated by gender or generation. For example, the use of an American label was associated with lower self-esteem for girls. Perhaps the aforementioned pressure for girls to retain heritage cultural values and traditions (e.g., Dion and Dion 2001; Supple et al. 2010) contributes to liabilities for their American identification. In addition, the link between American label use and academic motivation was moderated by nativity such that U.S.-born youth who use an American label reported higher motivation whereas such labels were associated with lower motivation for their foreign-born counterparts. Perhaps, for U.S-.born youth, there is a more comfortable match between using an American label and how they are perceived by others (e.g., peers, teachers), which can enhance their motivation to perform well in school. Foreign-born youth who use an American label could potentially see differences between themselves and their American-born peers which could ultimately undermine their academic adjustment. Another possible explanation is that foreign-born youth could experience unfair treatment or microaggressions in the very Western context of school, and identifying as an American in light of these negative experiences could have particularly impactful liabilities. In achieving an understanding of such links between American labels and outcomes, it is important to consider that complex associations might exist when incorporating more traditional indicators of identity.

Our overall findings suggest that American identity—whether defined by the use of an American label or by way of a continuous aggregate of American regard/centrality—is complex, influential in shaping youth development, and critical in terms of continued study. Indeed, one aspect of the complexity or possible struggle in Asian American youths’ identification as an American rests in the idea that a common implicit assumption held by both mainstream White Americans as well as people of color equates being American to being White (Devos and Mohamed 2014). Coupled with the pervasive perpetual foreigner stereotype that views Asian Americans and other ethnic groups as “aliens” or “foreigners” (Armenta et al. 2013; Goto et al. 2002), it is particularly vital to continue trying to understand whether and how U.S. adolescents with Asian ancestry might choose to identify (or not) with being American. Although our results provide some initial insight into these important identity processes, far more work should be done in examining possible links between American identity formation and actual perceptions of such common objectifying stereotypes, as well as how other experiences of negative discrimination might hinder American identity (Deaux 2008; Portes and Rumbaut 2001).

Future research could also target the areas in which the current study fell short, namely, with respect to its possible generalizability. Specifically, our sample was unique in its recruitment of youth residing in emerging communities of immigrants. While there are clear strengths in targeting such understudied populations, the relatively small number of Asian youth among these areas resulted in a panethnically defined sample that did not allow us to test or consider possible intra-ethnic variation. It is also unclear whether the processes uncovered here would operate similarly for youth in more traditional areas of migration. Indeed, prior work on the use of ethnic labels have found that adolescents from large metropolitan area of migration (e.g., Los Angeles) are more likely to incorporate American terms in their identity preferences as compared to youth in new immigrant areas (Kiang et al. 2011). More research should be conducted to continue examining such possible contextual effects.

We were also limited by our relatively small sample size. With a larger sample, we might have uncovered more variability in adolescents’ preferences for American-only, heritage-American, and panethnic-American labels. It is possible that qualitative differences between these variations exist, and our conceptualization of American labels could have limited by aggregating across these labels. It is also important to note that our sample size decreased even more in light of our follow-up wave of data collection. That said, the sensitivity analyses that we conducted after omitting this last wave of data entirely revealed few significant effects of missing data. The longitudinal, multiwave nature of our study was a strength, but we also note that approach was limited in its largely correlational nature.

Conclusion

Limitations notwithstanding, the present study contributes to the field’s limited knowledge of cultural identity formation among understudied Asian American adolescents and points to the importance of engaging in more research to further clarify the processes by which Asian youth from immigrant backgrounds come to define themselves as American. During adolescence, and even into emerging adulthood, adolescents’ sense of being American appears to be in great flux. The use of identity labels is developmentally salient as adolescents are faced with the almost constant demand to indicate their cultural background on various forms and documents in the real-world. Our findings suggest that the selection of these labels are not only important, practically speaking, but also have deep implications in terms of adjustment, with some variation across gender and generational status. It also appears that cultural labels and cultural identity are related, but reflect largely independent influences on youth development. Given the ever-growing ethnic diversity of the U.S. population, and the dynamic associations found between American identity, other indicators of cultural identity, and their independent and joint implications for other key developmental competencies in adolescents’ lives, more investigation into the ongoing processes and nuances of American labeling and identity is worthwhile.

References

Andresen, E. M., Malmgren, J. A., Carter, W. B., & Patrick, D. L. (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventative Medicine, 10(2), 77–84.

Armenta, B. E., Lee, R. M., Pituc, S. T., Jung, K. R., Park, I. J., Soto, J. A., Kim, S. Y., & Schwartz, S. J. (2013). Where are you from? A validation of the Foreigner Objectification Scale and the psychological correlates of foreigner objectification among Asian Americans and Latinos. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 19(2), 131–142.

Berry, J. W. (2003). Conceptual approaches to acculturation. In: K. M. Chun, P. B. Organista, & G. Marin (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research. (pp. 17–37). Washington, DC: APA. https://doi.org/10.1037/10472-004.

Birman, D., & Trickett, E. J. (2001). The process of acculturation in first generation immigrants: A study of Soviet Jewish refugee adolescents and parents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32, 456–477. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022101032004006.

Bowman, P. J., & Howard, C. (1985). Race-related socialization, motivation, and academic achievement: A study of Black youths in three-generation families. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 24(2), 134–141.

Bryk, A. S., & Raudenbush, S. W. (1992). Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Buriel, R, Cardoza, D. (1993). Mexican American ethnic labeling: An intrafamilial and intergenerational analysis. In: M. E. Bernal, & G. P. Knight (Eds.), Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. (pp. 197–210). Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Citrin, J., Wong, C., & Duff, B. (2001). The meaning of American national identity. In R. D. Ashmore, L. Jussim & D. Wilder (Eds.), Social identity, intergroup conflict, and conflict reduction (pp. 71–100). New York: Oxford University Press.

Costigan, C. L., & Su, T. (2004). Orthogonal versus linear models of acculturation among immigrant Chinese Canadians: A comparison of mothers, fathers, and children. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28, 518–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250444000234.

Deaux, K. (2008). To be an American: Immigration, hyphenation, and incorporation. Journal of Social Issues, 64(4), 925–943.

Devos, T., & Mohamed, H. (2014). Shades of American identity: Implicit relations between ethnic and national identities. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8, 739–754.

Dion, K. K., & Dion, K. L. (2001). Gender and cultural adaptation in immigrant families. Journal of Social Issues, 57(3), 511–521.

Doan, G. O., & Stephan, C. W. (2006). The functions of ethnic identity: A New Mexico Hispanic example. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 30(2), 229–241.

Eccles, J. S. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 75–146). San Francisco, CA: Freeman.

Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. Oxford, England: Norton & Co.

Espiritu, Y. L. (1993). Asian American panethnicity: Bridging institutions and identities. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Ethier, K. A., & Deaux, K. (1994). Negotiating social identity when contexts change: Maintaining identification and responding to threat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 243–251.

Fuligni, A. J., Kiang, L., Witkow, M. R., & Baldelomar, O. (2008). Stability and change in ethnic labeling among adolescents from Asian and Latin American immigrant families. Child Development, 79(4), 944–956.

Fuligni, A. J., Witkow, M. R., & Garcia, C. (2005). Ethnic identity and the academic adjustment of adolescents from Mexican, Chinese, and European backgrounds. Developmental Psychology, 41, 799–811. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.5.799.

Garcia Coll, C., Crnic, K., Lamberty, G., Wasik, B. H., Jenkins, R., Garcia, H. V., & McAdoo, H. P. (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67(5), 1891–1914.

Gartner, M., Kiang, L., & Supple, A. (2014). Prospective links between ethnic socialization, ethnic and American identity, and well-being among Asian-American adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(10), 1715–1727.

Goto, S. G., Gee, G. C., & Takeuchi, D. T. (2002). Strangers still? The experience of discrimination among Chinese Americans. Journal of Community Psychology, 30, 211–224.

Haritatos, J., & Benet-Martı́nez, V. (2002). Bicultural identities: The interface of cultural, personality, and socio-cognitive processes. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 598–606.

Kiang, L. (2008). Ethnic self-labeling in young American adults from Chinese backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(1), 97–111.

Kiang, L., Perreira, K. M., & Fuligni, A. J. (2011). Ethnic label use in adolescents from traditional and non-traditional immigrant receiving sites. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 719–729. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9597-3.

Kiang, L., Yip, T., & Fuligni, A. J. (2008). Multiple identities and adjustment in ethnically diverse young adults. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 18, 643–670. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2008.00575.x.

Kiang, L., Witkow, M. R., Baldelomar, O. A., & Fuligni, A. J. (2010). Change in ethnic identity across the high school years among adolescents with Latin American, Asian, and European backgrounds. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39, 683–693. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9429-5.

Kiang, L., Witkow, M. R., & Champagne, M. C. (2013). Normative changes in ethnic and American identities and links with adjustment among Asian American adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 49(9), 1713–1722.

Kiang, L., Witkow, M. R., Gonzalez, L. M., Stein, G. L., & Andrews, K. (2015). Changes in academic aspirations and expectations among Asian American adolescents. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 6(3), 252–262.

Kiang, L., & Supple, A. J. (2016). Theoretical perspectives on Asian American youth and families in rural and new immigrant destinations. In L. Crockett & G. Carlo (Eds.), Ethnic minority youth in the rural U.S. (71–88). Switzerland: Springer International Publishing.

Kiang, L., Cheah, C., Huynh, V., Wang, Y., & Yoshikawa, H. (2016). Annual review of Asian American psychology, 2015. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 7, 219–255.

Kibria, N. (2000). Race, ethnic options, and ethnic binds: Identity negotiations of second-generation Chinese and Korean Americans. Sociological Perspectives, 43(1), 77–95.

Kim, J. (2012). Asian American racial identity development theory. In C. L. Wijeyesinghe & B. W. Jackson, III (Eds.), New perspectives on racial identity development: Integrating emerging frameworks, 2nd Ed. (pp. 138–160). New York: New York University Press.

McBrien, J. L. (2005). Educational needs and barriers for refugee students in the United States: A review of literature. Review of Educational Research, 75(3), 329–364. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543075003329.

Mistry, J., Li, J., Yoshikawa, H., Tseng, V., Tirrell, J. M., Kiang, L., Mistry, R., & Wang, Y. (2016). An integrated conceptual framework for developmental research on Asian American children and youth. Child Development, 87, 1013–1032.

Mok, A., & Morris, M. W. (2010). Asian-Americans’ creative styles in Asian and American situations: Assimilative and contrastive responses as a function of bicultural identity integration. Management and Organization Review, 6(3), 371–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8784.2010.00190.x.

Mroczek, D. K., & Kolarz, C. M. (1998). The effect of age on positive and negative affect: a developmental perspective on happiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(5), 1333–1349.

Oetting, E. R., & Beauvais, F. (1991). Orthogonal cultural identification theory: The cultural identification of minority adolescents. The International Journal of the Addictions, 25, 655–685. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826089109077265.

Okamoto, D. G. (2006). Institutional panethnicity: Boundary formation in Asian-American organizing. Social Forces, 85, 1–25.

Pew Research Center. (2012). The rise of Asian Americans. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center.

Phinney, J. S. (1992). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7, 156–176.

Phinney, J. S. (2003). Ethnic identity and acculturation. In K. M. Chun, P. B. Organista & G. Marin (Eds.), Acculturation: Advances in theory, measurement, and applied research (pp. 63–81). Washington, DC: APA. https://doi.org/10.1037/10472-006.

Phinney, J., Cantu, C., & Kurtz, D. (1997). Ethnic and American identity as predictors of self-esteem among African American, Latino, and White adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 26, 165–185. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024500514834.

Portes, A., & Rumbaut, R. G. (2001). The story of the immigrant second generation: Legacies. New York: Russell Sage.

Pryor, C. B. (2001). New immigrants and refugees in American schools: Multiple voices. Childhood Education, 77, 275–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00094056.2001.10521650.

Qin‐Hilliard, D. B. (2003). Gendered expectations and gendered experiences: Immigrant students’ adaptation in schools. New Directions for Youth Development, 100, 91–109.

Qin, D. (2006). The role of gender in immigrant children’s educational adaptation. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 9(1), 8–19.

Rivas‐Drake, D., Seaton, E. K., Markstrom, C., Quintana, S., Syed, M., Lee, R. M., et al. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity in adolescence: Implications for psychosocial, academic, and health outcomes. Child Development, 85(1), 40–57.

Rosenberg, M. (1986). Conceiving the self. Melbourne, FL: Kreiger.

Rowley, S. J., Sellers, R. M., Chavous, T. M., & Smith, M. A. (1998). The relationship between racial identity and self-esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 715–724.

Rumbaut, R. G. (1994). The crucible within: Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and segmented assimilation among children of immigrants. International Migration Review, 28, 748–794.

Scheibe, E. (1983). Two types of successor relations between theories. Journal for General Philosophy of Science, 14(1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01801175.

Schwartz, S. J. (2007). The structure of identity consolidation: Multiple correlated constructs or one superordinate construct? Identity, 7, 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283480701319583.

Schwartz, S. J., & Zamboanga, B. L. (2008). Testing Berry’s model of acculturation: A confirmatory latent class approach. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 14(4), 275–285.

Sellers, R. M., Smith, M. A., Shelton, J. N., Rowley, S. A. J., & Chavous, T. M. (1998). Multidimensional Model of Racial Identity: A reconceptualization of African American racial identity. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 2, 18–39.

Supple, A. J., McCoy, S. Z., & Wang, Y. (2010). Parental influences on Hmong university students’ success. Hmong Studies Journal, 11, 1–37.

Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ying, Y., & Lee, P. A. (1999). The Development of ethnic identity in Asian American adolescents: Status and outcome. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 69(2), 194–208. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080421.

Yip, T., & Cross, W. E. (2004). A daily diary study of mental health and community involvement for three Chinese American social identities. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10(4), 394–408. https://doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.10.4.394.

Yip, T., Seaton, E. K., & Sellers, R. M. (2006). African American racial identity across the lifespan: Identity status, identity content, and depressive symptoms. Child Development, 77(5), 1504–1517.

Zha, B. X., Detzner, D. F., & Cleveland, M. J. (2004). Southeast Asian adolescents’ perceptions of immigrant parenting practices. Hmong Studies Journal, 5, 1–20.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the schools and individual adolescents who participated in the study.

Funding

Funding for the study, in part, was made possible by a Wake Forest University Social, Behavioral, Economic Sciences grant awarded to L.K.

Authors’ Contributions

L.K. designed and coordinated the larger study from which this manuscript is based. Both authors conceived of this manuscript’s initial research questions and M.W. performed the statistical analyses. L.K. and M.W. interpreted the data and drafted the manuscript. Both authors read and approved final manuscript.

Data Availability

The dataset analyzed in the current study is not publicly available, but the corresponding author will consider reasonable requests for data sharing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Kiang, L., Witkow, M.R. Identifying as American among Adolescents from Asian Backgrounds. J Youth Adolescence 47, 64–76 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0776-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0776-3